Signs and symptoms

Hepatitis has a broad spectrum of presentations that range from a complete lack of symptoms to severe liver failure. The acute form of hepatitis, generally caused by viral infection, is characterized by

Hepatitis has a broad spectrum of presentations that range from a complete lack of symptoms to severe liver failure. The acute form of hepatitis, generally caused by viral infection, is characterized by Acute hepatitis

Acute viral hepatitis follows three distinct phases: # The initial prodromal phase (preceding symptoms) involvesFulminant hepatitis

Fulminant hepatitis, or massive hepaticChronic hepatitis

Acute cases of hepatitis are seen to be resolved well within a six-month period. When hepatitis is continued for more than six months it is termed chronic hepatitis. Chronic hepatitis is often asymptomatic early in its course and is detected only by liver laboratory studies forCauses

Causes of hepatitis can be divided into the following major categories: infectious, metabolic, ischemic, autoimmune, genetic, and other. Infectious agents include viruses, bacteria, and parasites. Metabolic causes include prescription medications, toxins (most notably alcohol), andInfectious

Viral hepatitis

Parasitic hepatitis

Bacterial hepatitis

Bacterial infection of the liver commonly results in pyogenic liver abscesses, acute hepatitis, or granulomatous (or chronic) liver disease. Pyogenic abscesses commonly involveMetabolic

Alcoholic hepatitis

Excessive alcohol consumption is a significant cause of hepatitis and is the most common cause of cirrhosis in the U.S. Alcoholic hepatitis is within the spectrum ofToxic and drug-induced hepatitis

Many chemical agents, including medications, industrial toxins, and herbal and dietary supplements, can cause hepatitis. The spectrum of drug-induced liver injury varies from acute hepatitis to chronic hepatitis to acute liver failure. Toxins and medications can cause liver injury through a variety of mechanisms, including directDrug Induced Liver Injury Network

linked more than 16% of cases of hepatotoxicity to herbal and dietary supplements. In the United States, herbal and dietary supplements – unlike pharmaceutical drugs – are unregulated by the Food and Drug Administration. The National Institutes of Health maintains th

LiverTox

database for consumers to track all known prescription and non-prescription compounds associated with liver injury. Exposure to other hepatotoxins can occur accidentally or intentionally through ingestion, inhalation, and skin absorption. The industrial toxin carbon tetrachloride and the wild mushroom Amanita phalloides are other known hepatotoxins.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Non-alcoholic hepatitis is within the spectrum of non-alcoholic liver disease (NALD), which ranges in severity and reversibility fromultrasound steatosis score

In the early stages (as with NAFLD and early NASH), most patients are asymptomatic or have mild Quadrant (abdomen), right upper quadrant pain, and diagnosis is suspected on the basis of abnormal liver function tests. As the disease progresses, symptoms typical of chronic hepatitis may develop. While imaging can show fatty liver, only liver biopsy can demonstrate inflammation and fibrosis characteristic of NASH. 9 to 25% of patients with NASH develop cirrhosis. NASH is recognized as the third most common cause of liver disease in the United States.

Autoimmune

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic disease caused by an abnormal immune response against liver cells. The disease is thought to have a genetic predisposition as it is associated with certain human leukocyte antigens involved in the immune response. As in other autoimmune diseases, circulating Autoantibody, auto-antibodies may be present and are helpful in diagnosis. Auto-antibodies found in patients with autoimmune hepatitis include the Sensitivity and specificity, sensitive but less specific Anti-nuclear antibody, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), smooth muscle antibody (SMA), and Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, atypical perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA). Other autoantibodies that are less common but more specific to autoimmune hepatitis are the antibodies against liver kidney microsome 1 (LKM1) and soluble liver antigen (SLA). Autoimmune hepatitis can also be triggered by drugs (such asGenetic

Genetic causes of hepatitis include Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, HFE hereditary haemochromatosis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson's disease. In alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, a Co-dominant expression, co-dominant mutation in the gene for alpha-1-antitrypsin results in the abnormal accumulation of the mutant AAT protein within liver cells, leading to liver disease. Hemochromatosis and Wilson's disease are both autosomal recessive diseases involving abnormal storage of minerals. In hemochromatosis, excess amounts of iron accumulate in multiple body sites, including the liver, which can lead to cirrhosis. In Wilson's disease, excess amounts of copper accumulate in the liver and brain, causing cirrhosis and dementia. When the liver is involved, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency and Wilson's disease tend to present as hepatitis in the neonatal period or in childhood. Hemochromatosis typically presents in adulthood, with the onset of clinical disease usually after age 50.Ischemic hepatitis

Ischemic hepatitis (also known as shock liver) results from reduced blood flow to the liver as in shock, heart failure, or vascular insufficiency. The condition is most often associated with heart failure but can also be caused by Shock (circulatory), shock orOther

Hepatitis can also occur in neonates and is attributable to a variety of causes, some of which are not typically seen in adults. Congenital or perinatal infection with the hepatitis viruses, Toxoplasma gondii, toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and syphilis can cause neonatal hepatitis. Structural abnormalities such as biliary atresia and choledochal cysts can lead to Cholestasis, cholestatic liver injury leading to neonatal hepatitis. Inborn error of metabolism, Metabolic diseases such as Glycogen storage disease, glycogen storage disorders and Lysosomal storage disease, lysosomal storage disorders are also implicated. Neonatal hepatitis can be Idiopathy, idiopathic, and in such cases, biopsy often shows large multinucleated cells in the liver tissue. This disease is termed giant cell hepatitis and may be associated with viral infection, autoimmune disorders, and drug toxicity.Mechanism

The specific mechanism varies and depends on the underlying cause of the hepatitis. Generally, there is an initial insult that causes liver injury and activation of an inflammatory response, which can become chronic, leading to progressive fibrosis andViral hepatitis

The pathway by which hepatic viruses cause viral hepatitis is best understood in the case of hepatitis B and C. The viruses do not directly activate apoptosis (cell death). Rather, infection of liver cells activates the Innate immune system, innate and Adaptive immune system, adaptive arms of the immune system leading to an inflammatory response which causes cellular damage and death, including viral-induced apoptosis via the induction of the death receptor-mediated signaling pathway. Depending on the strength of the immune response, the types of immune cells involved and the ability of the virus to evade the body's defense, infection can either lead to clearance (acute disease) or persistence (chronic disease) of the virus. The chronic presence of the virus within liver cells results in multiple waves of

The pathway by which hepatic viruses cause viral hepatitis is best understood in the case of hepatitis B and C. The viruses do not directly activate apoptosis (cell death). Rather, infection of liver cells activates the Innate immune system, innate and Adaptive immune system, adaptive arms of the immune system leading to an inflammatory response which causes cellular damage and death, including viral-induced apoptosis via the induction of the death receptor-mediated signaling pathway. Depending on the strength of the immune response, the types of immune cells involved and the ability of the virus to evade the body's defense, infection can either lead to clearance (acute disease) or persistence (chronic disease) of the virus. The chronic presence of the virus within liver cells results in multiple waves of Steatohepatitis

Steatohepatitis is seen in both alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease and is the culmination of a cascade of events that began with injury. In the case of Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, this cascade is initiated by changes in metabolism associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and lipid dysregulation. InDiagnosis

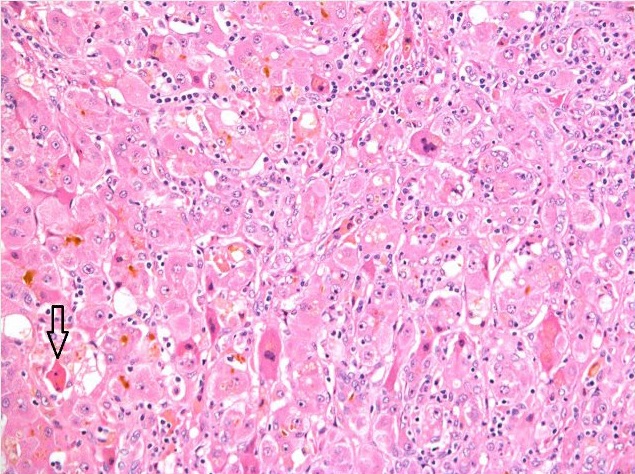

Diagnosis of hepatitis is made on the basis of some or all of the following: a person's signs and symptoms, medical history including sexual and substance use history, blood tests, Medical imaging, imaging, and liver biopsy. In general, for viral hepatitis and other acute causes of hepatitis, the person's blood tests and clinical picture are sufficient for diagnosis. For other causes of hepatitis, especially chronic causes, blood tests may not be useful. In this case, liver biopsy is the Gold standard (test), gold standard for establishing the diagnosis: Histopathology, histopathologic analysis is able to reveal the precise extent and pattern of inflammation and fibrosis. Biopsy is typically not the initial diagnostic test because it is invasive and is associated with a small but significant risk of bleeding that is increased in people with liver injury and cirrhosis.

Blood testing includes Liver function tests, liver enzymes, serology (i.e. for autoantibodies), nucleic acid testing (i.e. for hepatitis virus DNA/RNA), Blood chemistry study, blood chemistry, and complete blood count. Characteristic patterns of liver enzyme abnormalities can point to certain causes or stages of hepatitis. Generally, Aspartate transaminase, AST and Alanine transaminase, ALT are elevated in most cases of hepatitis regardless of whether the person shows any symptoms. The degree of elevation (i.e. levels in the hundreds vs. in the thousands), the predominance for AST vs. ALT elevation, and the ratio between AST and ALT are informative of the diagnosis.

Medical ultrasound, Ultrasound, CT scan, CT, and Magnetic resonance imaging, MRI can all identify steatosis (fatty changes) of the liver tissue and nodularity of the liver surface suggestive of cirrhosis. CT and especially MRI are able to provide a higher level of detail, allowing visualization and characterize such structures as vessels and tumors within the liver. Unlike steatosis and cirrhosis, no imaging test is able to detect liver inflammation (i.e. hepatitis) or fibrosis. Liver biopsy is the only definitive diagnostic test that is able to assess inflammation and fibrosis of the liver.

Diagnosis of hepatitis is made on the basis of some or all of the following: a person's signs and symptoms, medical history including sexual and substance use history, blood tests, Medical imaging, imaging, and liver biopsy. In general, for viral hepatitis and other acute causes of hepatitis, the person's blood tests and clinical picture are sufficient for diagnosis. For other causes of hepatitis, especially chronic causes, blood tests may not be useful. In this case, liver biopsy is the Gold standard (test), gold standard for establishing the diagnosis: Histopathology, histopathologic analysis is able to reveal the precise extent and pattern of inflammation and fibrosis. Biopsy is typically not the initial diagnostic test because it is invasive and is associated with a small but significant risk of bleeding that is increased in people with liver injury and cirrhosis.

Blood testing includes Liver function tests, liver enzymes, serology (i.e. for autoantibodies), nucleic acid testing (i.e. for hepatitis virus DNA/RNA), Blood chemistry study, blood chemistry, and complete blood count. Characteristic patterns of liver enzyme abnormalities can point to certain causes or stages of hepatitis. Generally, Aspartate transaminase, AST and Alanine transaminase, ALT are elevated in most cases of hepatitis regardless of whether the person shows any symptoms. The degree of elevation (i.e. levels in the hundreds vs. in the thousands), the predominance for AST vs. ALT elevation, and the ratio between AST and ALT are informative of the diagnosis.

Medical ultrasound, Ultrasound, CT scan, CT, and Magnetic resonance imaging, MRI can all identify steatosis (fatty changes) of the liver tissue and nodularity of the liver surface suggestive of cirrhosis. CT and especially MRI are able to provide a higher level of detail, allowing visualization and characterize such structures as vessels and tumors within the liver. Unlike steatosis and cirrhosis, no imaging test is able to detect liver inflammation (i.e. hepatitis) or fibrosis. Liver biopsy is the only definitive diagnostic test that is able to assess inflammation and fibrosis of the liver.

Viral hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is primarily diagnosed through blood tests for levels of viral antigens (such as the HBsAg, hepatitis B surface or HBcAg, core antigen), anti-viral antibodies (such as the anti-hepatitis B surface antibody or anti-hepatitis A antibody), or viral DNA/RNA. In early infection (i.e. within 1 week), Immunoglobulin M, IgM antibodies are found in the blood. In late infection and after recovery, Immunoglobulin G, IgG antibodies are present and remain in the body for up to years. Therefore, when a patient is positive for IgG antibody but negative for IgM antibody, he is considered Immunity (medical), immune from the virus via either prior infection and recovery or prior vaccination. In the case of hepatitis B, blood tests exist for multiple virus antigens (which are different components of the :File:HBV.png, virion particle) and antibodies. The combination of antigen and antibody positivity can provide information about the stage of infection (acute or chronic), the degree of viral replication, and the infectivity of the virus.Alcoholic versus non-alcoholic

The most apparent distinguishing factor between Alcoholic hepatitis, alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a history of excessive alcohol use. Thus, in patients who have no or negligible alcohol use, the diagnosis is unlikely to be alcoholic hepatitis. In those who drink alcohol, the diagnosis may just as likely be alcoholic or nonalcoholic hepatitis especially if there is concurrent obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. In this case, alcoholic and nonalcoholic hepatitis can be distinguished by the pattern of liver enzyme abnormalities; specifically, in alcoholic steatohepatitis AST>ALT with ratio of AST:ALT>2:1 while in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis ALT>AST with ratio of ALT:AST>1.5:1. Liver biopsies show identical findings in patients with ASH and NASH, specifically, the presence of Granulocyte, polymorphonuclear infiltration, hepatocyte necrosis and apoptosis in the form of ballooning degeneration, Mallory body, Mallory bodies, and fibrosis around veins and sinuses.Virus screening

The purpose of screening for viral hepatitis is to identify people infected with the disease as early as possible, even before symptoms and transaminase elevations may be present. This allows for early treatment, which can both prevent disease progression and decrease the likelihood of transmission to others.Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A causes an acute illness that does not progress to chronic liver disease. Therefore, the role of screening is to assess immune status in people who are at high risk of contracting the virus, as well as in people with known liver disease for whom hepatitis A infection could lead to liver failure. People in these groups who are not already immune can receive the hepatitis A vaccine. Those at high risk and in need of screening include: * People with poor sanitary habits such as not washing hands after using the restroom or changing diapers * People who do not have access to clean water * People in close contact (either living with or having sexual contact) with someone who has hepatitis A * People who use illicit drugs * People with liver disease * People traveling to an area with endemic hepatitis A The presence of anti-hepatitis A Immunoglobulin G, IgG in the blood indicates past infection with the virus or prior vaccination.Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, World Health Organization, WHO, United States Preventive Services Task Force, USPSTF, AASLD, and American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ACOG recommend screening people at high risk for hepatitis C infection. These populations include people who are:

* Intravenous drug users (past or current)

* Intranasal illicit drug users

* HIV-positive

* Men who have sex with men

* Incarcerated, or who have been in the past

* On long-term hemodialysis, or who have been in the past

* Recipients of tattoos in an "unregulated setting"

* Recipients of blood products or organs prior to 1992 in the United States

* Adults in the United States born between 1945 and 1965

* Born to HCV-positive mothers

* Pregnant, and engaging in high-risk behaviors

* Workers in a healthcare setting who have had a needlestick injury

* Blood or organ donors.

* Sex workers

For people in the groups above whose exposure is ongoing, screening should be periodic, though there is no set optimal screening interval. The AASLD recommends screening men who have sex with men who are HIV-positive annually. People born in the US between 1945 and 1965 should be screened once (unless they have other exposure risks).

Screening consists of a blood test that detects anti-hepatitis C virus antibody. If anti-hepatitis C virus antibody is present, a confirmatory test to detect HCV RNA indicates chronic disease.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, World Health Organization, WHO, United States Preventive Services Task Force, USPSTF, AASLD, and American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ACOG recommend screening people at high risk for hepatitis C infection. These populations include people who are:

* Intravenous drug users (past or current)

* Intranasal illicit drug users

* HIV-positive

* Men who have sex with men

* Incarcerated, or who have been in the past

* On long-term hemodialysis, or who have been in the past

* Recipients of tattoos in an "unregulated setting"

* Recipients of blood products or organs prior to 1992 in the United States

* Adults in the United States born between 1945 and 1965

* Born to HCV-positive mothers

* Pregnant, and engaging in high-risk behaviors

* Workers in a healthcare setting who have had a needlestick injury

* Blood or organ donors.

* Sex workers

For people in the groups above whose exposure is ongoing, screening should be periodic, though there is no set optimal screening interval. The AASLD recommends screening men who have sex with men who are HIV-positive annually. People born in the US between 1945 and 1965 should be screened once (unless they have other exposure risks).

Screening consists of a blood test that detects anti-hepatitis C virus antibody. If anti-hepatitis C virus antibody is present, a confirmatory test to detect HCV RNA indicates chronic disease.

Hepatitis D

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, World Health Organization, WHO, United States Preventive Services Task Force, USPSTF, AASLD, and American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ACOG recommend screening people at high risk for hepatitis D infection. These populations include people who are: * Intravenous drug users (past or current) * Intranasal illicit drug users * Incarcerated, or who have been in the past * Workers in a healthcare setting who have had a needlestick injury * Blood or organ donors. * Sex workersHepatitis D is extremely rare. Symptoms include chronic diarrhea, anal and intestinal blisters, purple urine, and burnt popcorn scented breath. Screening consists of a blood test that detects the anti-hepitits D virus antibbody. If anti-hepitits D virus antibody is present, a confirmatory test to detect HDV RNA DNA inidicates chronic disease.

Prevention

Vaccines

Hepatitis A

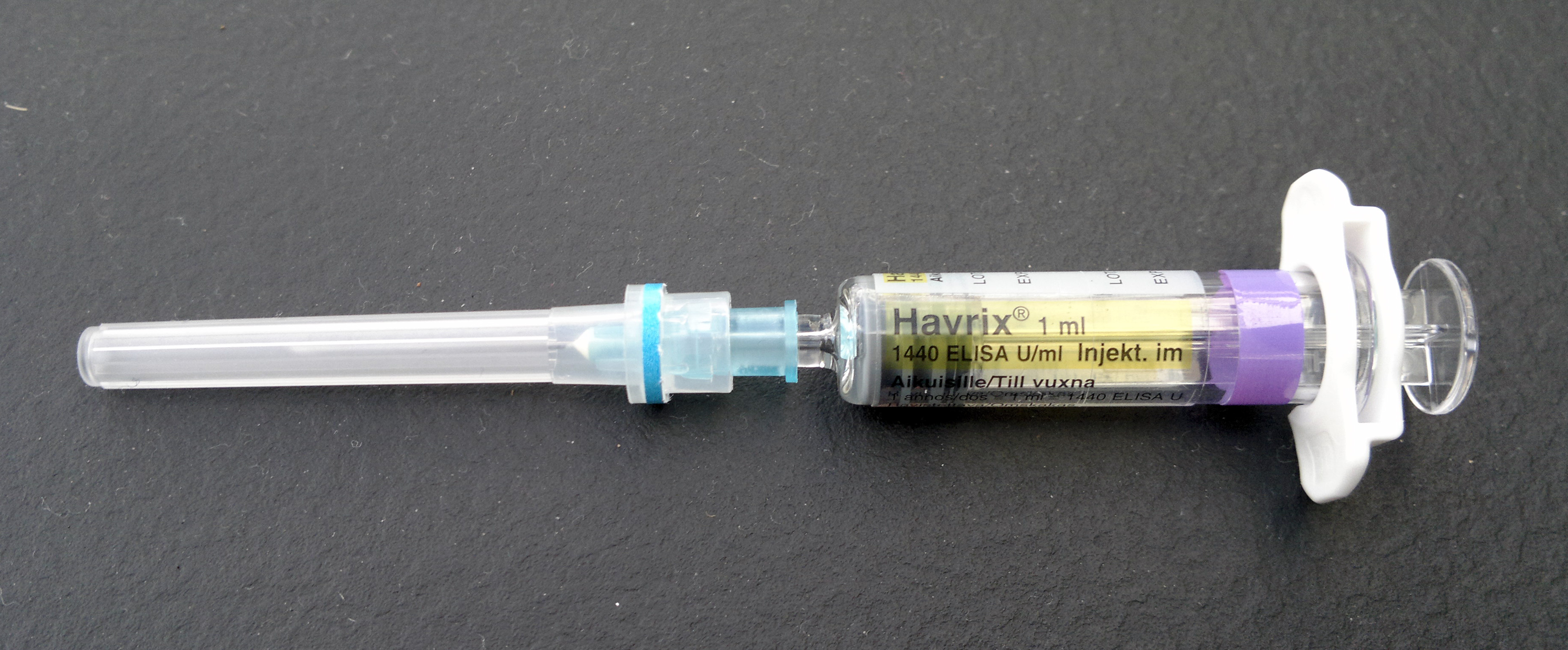

The CDC recommends the hepatitis A vaccine for all children beginning at age one, as well as for those who have not been previously immunized and are at high risk for contracting the disease.

For children 12 months of age or older, the vaccination is given as a shot into the muscle in two doses 6–18 months apart and should be started before the age 24 months. The dosing is slightly different for adults depending on the type of the vaccine. If the vaccine is for hepatitis A only, two doses are given 6–18 months apart depending on the manufacturer. If the vaccine is Hepatitis A vaccine, combined hepatitis A and hepatitis B, up to 4 doses may be required.

The CDC recommends the hepatitis A vaccine for all children beginning at age one, as well as for those who have not been previously immunized and are at high risk for contracting the disease.

For children 12 months of age or older, the vaccination is given as a shot into the muscle in two doses 6–18 months apart and should be started before the age 24 months. The dosing is slightly different for adults depending on the type of the vaccine. If the vaccine is for hepatitis A only, two doses are given 6–18 months apart depending on the manufacturer. If the vaccine is Hepatitis A vaccine, combined hepatitis A and hepatitis B, up to 4 doses may be required.

Hepatitis B

The CDC recommends the routine vaccination of all children under the age of 19 with the hepatitis B vaccine. They also recommend it for those who desire it or are at high risk.

Routine vaccination for hepatitis B starts with the first dose administered as a shot into the muscle before the newborn is discharged from the hospital. An additional two doses should be administered before the child is 18 months.

For babies born to a mother with hepatitis B surface antigen positivity, the first dose is unique – in addition to the vaccine, the hepatitis immune globulin should also be administered, both within 12 hours of birth. These newborns should also be regularly tested for infection for at least the first year of life.

There is also a combination formulation that includes Hepatitis A vaccine, both hepatitis A and B vaccines.

The CDC recommends the routine vaccination of all children under the age of 19 with the hepatitis B vaccine. They also recommend it for those who desire it or are at high risk.

Routine vaccination for hepatitis B starts with the first dose administered as a shot into the muscle before the newborn is discharged from the hospital. An additional two doses should be administered before the child is 18 months.

For babies born to a mother with hepatitis B surface antigen positivity, the first dose is unique – in addition to the vaccine, the hepatitis immune globulin should also be administered, both within 12 hours of birth. These newborns should also be regularly tested for infection for at least the first year of life.

There is also a combination formulation that includes Hepatitis A vaccine, both hepatitis A and B vaccines.

Other

There are currently no vaccines available in the United States for hepatitis C or E. In 2015, a group in China published an article regarding the development of a vaccine for hepatitis E. As of March 2016, the United States government was in the process of recruiting participants for the Phases of clinical research, phase IV trial of the hepatitis E vaccine.Behavioral changes

Hepatitis A

Because hepatitis A is transmitted primarily through the Fecal-oral route, oral-fecal route, the mainstay of prevention aside from vaccination is good hygiene, access to clean water and proper handling of sewage.Hepatitis B and C

As hepatitis B and C are transmitted through blood and multiple bodily fluids, prevention is aimed at screening blood prior to Blood transfusion, transfusion, abstaining from the use of injection drugs, safe needle and sharps practices in healthcare settings, and safe sex practices.Hepatitis D

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is spread primarily through the oral-fecal route but may also be spread by blood and from mother to fetus. The mainstay of hepatitis E prevention is similar to that for hepatitis A (namely, good hygiene and clean water practices).Alcoholic hepatitis

As excessive alcohol consumption can lead to hepatitis and cirrhosis, the following are maximal recommendations for alcohol consumption: * Women – ≤ 3 drinks on any given day and ≤ 7 drinks per week * Men – ≤ 4 drinks on any given day and ≤ 14 drinks per weekSuccesses

Hepatitis A

In the United States, universal immunization has led to a two-thirds decrease in hospital admissions and medical expenses due to hepatitis A.Hepatitis B

In the United States new cases of hepatitis B decreased 75% from 1990 to 2004. The group that saw the greatest decrease was children and adolescents, likely reflecting the implementation of the 1999 guidelines.Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C infections each year had been declining since the 1980s, but began to increase again in 2006. The data are unclear as to whether the decline can be attributed to needle exchange programmes.Alcoholic hepatitis

Because people with alcoholic hepatitis may have no symptoms, it can be difficult to diagnose and the number of people with the disease is probably higher than many estimates. Programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous have been successful in decreasing death due to

Because people with alcoholic hepatitis may have no symptoms, it can be difficult to diagnose and the number of people with the disease is probably higher than many estimates. Programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous have been successful in decreasing death due to Treatment

The treatment of hepatitis varies according to the type, whether it is acute or chronic, and the severity of the disease. * Activity: Many people with hepatitis prefer bed rest, though it is not necessary to avoid all physical activity while recovering. * Diet: A high-calorie diet is recommended. Many people develop nausea and cannot tolerate food later in the day, so the bulk of intake may be concentrated in the earlier part of the day. In the acute phase of the disease, intravenous feeding may be needed if patients cannot tolerate food and have poor oral intake subsequent to nausea and vomiting. * Drugs: People with hepatitis should avoid taking drugs metabolized by the liver. Glucocorticoids are not recommended as a treatment option for acute viral hepatitis and may even cause harm, such as development of chronic hepatitis. * Precautions: Universal precautions should be observed. Isolation is usually not needed, except in cases of hepatitis A and E who have fecal incontinence, and in cases of hepatitis B and C who have uncontrolled bleeding.Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A usually does not progress to a chronic state, and rarely requires hospitalization. Treatment is supportive and includes such measures as providing intravenous (IV) hydration and maintaining adequate nutrition. Rarely, people with the hepatitis A virus can rapidly develop liver failure, termed ''fulminant hepatic failure'', especially the elderly and those who had a pre-existing liver disease, especially hepatitis C. Mortality risk factors include greater age and chronic hepatitis C. In these cases, more aggressive supportive therapy and liver transplant may be necessary.Hepatitis B

Acute

In healthy patients, 95–99% recover with no long-lasting effects, and antiviral treatment is not warranted. Age and comorbid conditions can result in a more prolonged and severe illness. Certain patients warrant hospitalization, especially those who present with clinical signs of ascites, peripheral edema, and hepatic encephalopathy, and laboratory signs of hypoglycemia, prolonged prothrombin time, low serum Albumin human, albumin, and very high serum bilirubin. In these rare, more severe acute cases, patients have been successfully treated with antiviral therapy similar to that used in cases of chronic hepatitis B, with nucleoside analogues such as entecavir or Tenofovir disoproxil, tenofovir. As there is a dearth of clinical trial data and the drugs used to treat are prone to developing Drug resistance, resistance, experts recommend reserving treatment for severe acute cases, not mild to moderate.Chronic

Chronic hepatitis B management aims to control viral replication, which is correlated with progression of disease. Seven drugs are approved in the United States: * Injectable interferon alpha was the first therapy approved for chronic hepatitis B. It has several side effects, most of which are reversible with removal of therapy, but it has been supplanted by newer treatments for this indication. These include long-acting interferon bound to polyethylene glycol (pegylated interferon) and the oral nucleoside analogues. * Pegylated interferon (PEG IFN) is dosed just once a week as a subcutaneous injection and is both more convenient and effective than standard interferon. Although it does not develop resistance as do many of the oral antivirals, it is poorly tolerated and requires close monitoring. PEG IFN is estimated to cost about $18,000 per year in the United States, compared to $2,500–8,700 for the oral medications. Its treatment duration is 48 weeks, unlike oral antivirals which require indefinite treatment for most patients (minimum one year). PEG IFN is not effective in patients with high levels of viral activity and cannot be used in immunosuppressed patients or those with cirrhosis. * Lamivudine was the first approved oral nucleoside analogue. While effective and potent, lamivudine has been replaced by newer, more potent treatments in the Western world and is no longer recommended as first-line treatment. It is still used in areas where newer agents either have not been approved or are too costly. Generally, the course of treatment is a minimum of one year with a minimum of six additional months of "consolidation therapy." Based on viral response, longer therapy may be required, and certain patients require indefinite long-term therapy. Due to a less robust response in Asian patients, consolidation therapy is recommended to be extended to at least a year. All patients should be monitored for viral reactivation, which if identified, requires restarting treatment. Lamivudine is generally safe and well tolerated. Many patients develop resistance, which is correlated with longer treatment duration. If this occurs, an additional antiviral is added. Lamivudine as a single treatment is contraindicated in patients coinfected with HIV, as resistance develops rapidly, but it can be used as part of a multidrug regimen. * Adefovir dipivoxil, a nucleotide analogue, has been used to supplement lamivudine in patients who develop resistance, but is no longer recommended as first-line therapy. * Entecavir is safe, well tolerated, less prone to developing resistance, and the most potent of the existing hepatitis B antivirals; it is thus a first-line treatment choice. It is not recommended for lamivudine-resistant patients or as monotherapy in patients who are HIV positive. * Telbivudine is effective but not recommended as first-line treatment; as compared to entecavir, it is both less potent and more resistance prone. * Tenofovir disoproxil, Tenofovir is a nucleotide analogue and an antiretroviral drug that is also used to treat HIV infection. It is preferred to adefovir both in lamivudine-resistant patients and as initial treatment since it is both more potent and less likely to develop resistance. First-line treatments currently used include PEG IFN, entecavir, and tenofovir, subject to patient and physician preference. Treatment initiation is guided by recommendations issued by The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and is based on detectable viral levels, HBeAg positive or negative status, Alanine transaminase, ALT levels, and in certain cases, family history of HCC and liver biopsy. In patients with compensated cirrhosis, treatment is recommended regardless of HBeAg status or ALT level, but recommendations differ regarding HBV DNA levels; AASLD recommends treating at DNA levels detectable above 2x103 IU/mL; EASL and WHO recommend treating when HBV DNA levels are detectable at any level. In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, treatment and evaluation for liver transplantation are recommended in all cases if HBV DNA is detectable. Currently, multidrug treatment is not recommended in treatment of chronic HBV as it is no more effective in the long term than individual treatment with entecavir or tenofovir.Hepatitis C

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD-IDSA) recommend antiviral treatment for all patients with chronic hepatitis C infection except for those with additional chronic medical conditions that limit their life expectancy. Once it is acquired, persistence of the hepatitis C virus is the rule, resulting in chronic hepatitis C. The goal of treatment is prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The best way to reduce the long-term risk of HCC is to achieve sustained virological response (SVR). SVR is defined as an undetectable viral load at 12 weeks after treatment completion and indicates a cure. Currently available treatments include indirect and direct acting antiviral drugs. The indirect acting antivirals include pegylated interferon (PEG IFN) and ribavirin (RBV), which in combination have historically been the basis of therapy for HCV. Duration of and response to these treatments varies based on genotype. These agents are poorly tolerated but are still used in some resource-poor areas. In high-resource countries, they have been supplanted by direct acting antiviral agents, which first appeared in 2011; these agents target proteins responsible for viral replication and include the following three classes: * NS3/4A Protease inhibitor (pharmacology), protease inhibitors, including telaprevir, boceprevir, simeprevir, and others * NS5A inhibitors, including ledipasvir, daclatasvir, and others * NS5B polymerase inhibitors, including sofosbuvir, dasabuvir, and others These drugs are used in various combinations, sometimes combined with ribavirin, based on the patient's genotype, delineated as genotypes 1–6. Genotype 1 (GT1), which is the most prevalent genotype in the United States and around the world, can now be cured with a direct acting antiviral regimen. First-line therapy for GT1 is a combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (SOF/LDV) for 12 weeks for most patients, including those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. Certain patients with early disease need only 8 weeks of treatment while those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis who have not responded to prior treatment require 24 weeks. Cost remains a major factor limiting access to these drugs, particularly in low-resource nations; the cost of the 12-week GT1 regimen (SOF/LDV) has been estimated at US$94,500.Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D is difficult to treat, and effective treatments are lacking. Interferon alpha has proven effective at inhibiting viral activity but only on a temporary basis.Hepatitis E

Similar to hepatitis A, treatment of hepatitis E is supportive and includes rest and ensuring adequate nutrition and hydration. Hospitalization may be required for particularly severe cases or for pregnant women.

Similar to hepatitis A, treatment of hepatitis E is supportive and includes rest and ensuring adequate nutrition and hydration. Hospitalization may be required for particularly severe cases or for pregnant women.

Alcoholic hepatitis

First-line treatment of alcoholic hepatitis is treatment of alcoholism. For those who abstain completely from alcohol, reversal of liver disease and a longer life are possible; patients at every disease stage have been shown to benefit by prevention of additional liver injury. In addition to referral to psychotherapy and other treatment programs, treatment should include nutritional and psychosocial evaluation and treatment. Patients should also be treated appropriately for related signs and symptoms, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and infection. Severe alcoholic hepatitis has a poor prognosis and is notoriously difficult to treat. Without any treatment, 20-50% of patients may die within a month, but evidence shows treatment may extend life beyond one month (i.e., reduce short-term mortality). Available treatment options include pentoxifylline (PTX), which is a nonspecific TNF inhibitor, corticosteroids, such as prednisone or prednisolone (CS), corticosteroids with ''N-Acetylcysteine, N''N-Acetylcysteine, -acetylcysteine (CS with NAC), and corticosteroids with pentoxifylline (CS with PTX). Data suggest that CS alone or CS with NAC are most effective at reducing short-term mortality. Unfortunately, corticosteroids are contraindicated in some patients, such as those who have active gastrointestinal bleeding, infection, kidney failure, or pancreatitis. In these cases PTX may be considered on a case-by-case basis in lieu of CS; some evidence shows PTX is better than no treatment at all and may be comparable to CS while other data show no evidence of benefit over placebo. Unfortunately, there are currently no drug treatments that decrease these patients' risk of dying in the longer term, at 3–12 months and beyond. Weak evidence suggests Milk Thistle, milk thistle extracts may improve survival in alcoholic liver disease and improve certain liver tests (serum bilirubin and Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, GGT) without causing side effects, but a firm recommendation cannot be made for or against milk thistle without further study. The modified Maddrey's discriminant function may be used to evaluate the severity and prognosis in alcoholic hepatitis and evaluates the efficacy of using alcoholic hepatitis corticosteroid treatment.Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is commonly treated by immunosuppressants such as the corticosteroids prednisone or prednisolone, the active version of prednisolone that does not require liver synthesis, either alone or in combination with azathioprine, and some have suggested the combination therapy is preferred to allow for lower doses of corticosteroids to reduce associated side effects, although the result of treatment efficacy is comparative. Treatment of autoimmune hepatitis consists of two phases; an initial and maintenance phase. The initial phase consists of higher doses of corticosteroids which are tapered down over a number of weeks to a lower dose. If used in combination, azathioprine is given during the initial phase as well. Once the initial phase has been completed, a maintenance phase that consists of lower dose corticosteroids, and in combination therapy, azathioprine until liver blood markers are normalized. Treatment results in 66-91% of patients achieving normal liver test values in two years, with the average being 22 months.Prognosis

Acute hepatitis

Nearly all patients with hepatitis A infections recover completely without complications if they were healthy prior to the infection. Similarly, acute hepatitis B infections have a favorable course towards complete recovery in 95–99% of patients. Certain factors may portend a poorer outcome, such as co-morbid medical conditions or initial presenting symptoms of ascites, edema, or encephalopathy. Overall, the mortality rate for acute hepatitis is low: ~0.1% in total for cases of hepatitis A and B, but rates can be higher in certain populations (super infection with both hepatitis B and D, pregnant women, etc.). In contrast to hepatitis A & B, hepatitis C carries a much higher risk of progressing to chronic hepatitis, approaching 85–90%. Cirrhosis has been reported to develop in 20–50% of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Other rare complications of acute hepatitis include pancreatitis, aplastic anemia, peripheral neuropathy, and myocarditis.Fulminant hepatitis

Despite the relatively benign course of most viral cases of hepatitis, fulminant hepatitis represents a rare but feared complication. Fulminant hepatitis most commonly occurs in hepatitis B, D, and E. About 1–2% of cases of hepatitis E can lead to fulminant hepatitis, but pregnant women are particularly susceptible, occurring in up to 20% of cases. Mortality rates in cases of fulminant hepatitis rise over 80%, but those patients that do survive often make a complete recovery. Liver transplantation can be life-saving in patients with fulminant liver failure. Hepatitis D infections can transform benign cases of hepatitis B into severe, progressive hepatitis, a phenomenon known as superinfection.Chronic hepatitis

Acute hepatitis B infections become less likely to progress to chronic forms as the age of the patient increases, with rates of progression approaching 90% in vertically transmitted cases of infants compared to 1% risk in young adults. Overall, the five-year survival rate for chronic hepatitis B ranges from 97% in mild cases to 55% in severe cases with cirrhosis. Most patients who acquire hepatitis D at the same time as hepatitis B (co-infection) recover without developing a chronic infection. In people with hepatitis B who later acquire hepatitis D (superinfection), chronic infection is much more common at 80-90%, and liver disease progression is accelerated. Chronic hepatitis C progresses towards cirrhosis, with estimates of cirrhosis prevalence of 16% at 20 years after infection. While the major causes of mortality in hepatitis C is end stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma is an important additional long term complication and cause of death in chronic hepatitis. Rates of mortality increase with progression of the underlying liver disease. Series of patients with compensated cirrhosis due to HCV have shown 3,5, and 10-year survival rates of 96, 91, and 79% respectively. The 5-year survival rate drops to 50% upon if the cirrhosis becomes decompensated.Epidemiology

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is found throughout the world and manifests as large outbreaks and epidemics associated with fecal contamination of water and food sources. Hepatitis A viral infection is predominant in children ages 5–14 with rare infection of infants. Infected children have little to no apparent clinical illness, in contrast to adults in whom greater than 80% are symptomatic if infected. Infection rates are highest in low resource countries with inadequate public sanitation and large concentrated populations. In such regions, as much as 90% of children younger than 10 years old have been infected and are immune, corresponding both to lower rates of clinically symptomatic disease and outbreaks. The availability of a childhood vaccine has significantly reduced infections in the United States, with incidence declining by more than 95% as of 2013. Paradoxically, the highest rates of new infection now occur in young adults and adults who present with worse clinical illness. Specific populations at greatest risk include: travelers to endemic regions, men who have sex with men, those with occupational exposure to non-human primates, people with clotting disorders who have received clotting factors, people with history of chronic liver disease in whom co-infection with hepatitis A can lead to fulminant hepatitis, and intravenous drug users (rare).Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

Chronic hepatitis C is a major cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. It is a common medical reason for liver transplantation due to its severe complications. It is estimated that 130–180 million people in the world are affected by this disease representing a little more than 3% of the world population. In the developing regions of Africa, Asia and South America, prevalence can be as high as 10% of the population. In Egypt, rates of hepatitis C infection as high as 20% have been documented and are associated with Iatrogenesis, iatrogenic contamination related to schistosomiasis treatment in the 1950s–1980s. Currently in the United States, approximately 3.5 million adults are estimated to be infected. Hepatitis C is particularly prevalent among people born between 1945 and 1965, a group of about 800,000 people, with prevalence as high as 3.2% versus 1.6% in the general U.S. population. Most chronic carriers of hepatitis C are unaware of their infection status. The most common mode of transmission of hepatitis C virus is exposure to blood products via blood transfusions (prior to 1992) and intravenous drug injection. A history of intravenous drug injection is the most important risk factor for chronic hepatitis C. Other susceptible populations include those engaged in high-risk sexual behavior, infants of infected mothers, and healthcare workers.

Chronic hepatitis C is a major cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. It is a common medical reason for liver transplantation due to its severe complications. It is estimated that 130–180 million people in the world are affected by this disease representing a little more than 3% of the world population. In the developing regions of Africa, Asia and South America, prevalence can be as high as 10% of the population. In Egypt, rates of hepatitis C infection as high as 20% have been documented and are associated with Iatrogenesis, iatrogenic contamination related to schistosomiasis treatment in the 1950s–1980s. Currently in the United States, approximately 3.5 million adults are estimated to be infected. Hepatitis C is particularly prevalent among people born between 1945 and 1965, a group of about 800,000 people, with prevalence as high as 3.2% versus 1.6% in the general U.S. population. Most chronic carriers of hepatitis C are unaware of their infection status. The most common mode of transmission of hepatitis C virus is exposure to blood products via blood transfusions (prior to 1992) and intravenous drug injection. A history of intravenous drug injection is the most important risk factor for chronic hepatitis C. Other susceptible populations include those engaged in high-risk sexual behavior, infants of infected mothers, and healthcare workers.

Hepatitis D

TheHepatitis E

Similar to Hepatitis A,Alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) in its severe form has a one-month mortality as high as 50%. Most people who develop AH are men but women are at higher risk of developing AH and its complications likely secondary to high body fat and differences in alcohol metabolism. Other contributing factors include younger age <60, binge pattern drinking, poor nutritional status, obesity and hepatitis C co-infection. It is estimated that as much as 20% of people with AH are also infected with hepatitis C. In this population, the presence of hepatitis C virus leads to more severe disease with faster progression to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and increased mortality. Obesity increases the likelihood of progression to cirrhosis in cases of alcoholic hepatitis. It is estimated that 70% of people who have AH will progress to cirrhosis.Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is projected to become the top reason for liver transplantation in the United States by 2020, supplanting chronic liver disease due to hepatitis C. About 20–45% of the U.S. population have NAFLD and 6% have NASH. The estimated prevalence of NASH in the world is 3–5%. Of NASH patients who developHistory

Early observations

Initial accounts of a syndrome that we now think is likely to be hepatitis begin to occur around 3000 B.C. Clay tablets that served as medical handbooks for the ancient Sumerians described the first observations of jaundice. The Sumerians believed that the liver was the home of the soul, and attributed the findings of jaundice to the attack of the liver by a devil named Ahhazu. Around 400 B.C., Hippocrates recorded the first documentation of an epidemic jaundice, in particular noting the uniquely fulminant course of a cohort of patients who all died within two weeks. He wrote, "The bile contained in the liver is full of phlegm and blood, and erupts...After such an eruption, the patient soon raves, becomes angry, talks nonsense and barks like a dog." Given the poor sanitary conditions of war, infectious jaundice played a large role as a major cause of mortality among troops in the Napoleonic Wars, the American Revolutionary War, and both World Wars. During World War II, estimates of soldiers affected by hepatitis were upwards of 10 million. During World War II, soldiers received vaccines against diseases such as yellow fever, but these vaccines were stabilized with human serum, presumably contaminated with hepatitis viruses, which often created epidemics of hepatitis. It was suspected these epidemics were due to a separate infectious agent, and not due to the yellow fever virus itself, after noting 89 cases of jaundice in the months after vaccination out of a total 3,100 patients that were vaccinated. After changing the seed virus strain, no cases of jaundice were observed in the subsequent 8,000 vaccinations.Willowbrook State School experiments

A New York University researcher named Saul Krugman continued this research into the 1950s and 1960s, most infamously with his experiments on mentally disabled children at the Willowbrook State School in New York, a crowded urban facility where hepatitis infections were highly endemic to the student body. Krugman injected students with gamma globulin, a type of antibody. After observing the temporary protection against infection this antibody provided, he then tried injected live hepatitis virus into students. Krugman also controversially took feces from infected students, blended it into milkshakes, and fed it to newly admitted children. His research was received with much controversy, as people protested the questionable ethics surrounding the chosen target population. Henry K. Beecher, Henry Beecher was one of the foremost critics in an article in the ''New England Journal of Medicine'' in 1966, arguing that parents were unaware to the risks of consent and that the research was done to benefit others at the expense of children. Moreover, he argued that poor families with mentally disabled children often felt pressured to join the research project to gain admission to the school, with all of the educational and support resources that would come along with it. Others in the medical community spoke out in support of Krugman's research in terms of its widespread benefits and understanding of the hepatitis virus, and Willowbrook continues to be a commonly cited example in debates about medical ethics.Australia antigen

The next insight regarding hepatitis B was a serendipitous one by Baruch Samuel Blumberg, Dr. Baruch Blumberg, a researcher at the NIH who did not set out to research hepatitis, but rather studied lipoprotein genetics. He travelled across the globe collecting blood samples, investigating the interplay between disease, environment, and genetics with the goal of designing targeted interventions for at-risk people that could prevent them from getting sick. He noticed an unexpected interaction between the blood of a patient with Haemophilia, hemophilia that had received multiple transfusions and a protein found in the blood of an indigenous Australian person. He named the protein the "Australia antigen" and made it the focus of his research. He found a higher prevalence of the protein in the blood of patients from developing countries, compared to those from developed ones, and noted associations of the antigen with other diseases like leukemia and Down Syndrome. Eventually, he came to the unifying conclusion that the Australia antigen was associated with viral hepatitis. In 1970, David Dane first isolated the hepatitis B virion at London's Middlesex Hospital, and named the virion the 42-nm "Dane particle". Based on its association with the surface of the hepatitis B virus, the Australia antigen was renamed to "hepatitis B surface antigen" or HBsAg. Blumberg continued to study the antigen, and eventually developed the first hepatitis B vaccine using plasma rich in HBsAg, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1976.Society and culture

Economic burden

Overall, hepatitis accounts for a significant portion of healthcare expenditures in both developing and developed nations, and is expected to rise in several developing countries. While hepatitis A infections are self-limited events, they are associated with significant costs in the United States. It has been estimated that Direct cost, direct and indirect costs are approximately $1817 and $2459 respectively per case, and that an average of 27 work days is lost per infected adult. A 1997 report demonstrated that a single hospitalization related to hepatitis A cost an average of $6,900 and resulted in around $500 million in total annual healthcare costs. Cost effectiveness studies have found widespread vaccination of adults to not be feasible, but have stated that a combination hepatitis A and B vaccination of children and at risk groups (people from endemic areas, healthcare workers) may be. Hepatitis B accounts for a much larger percentage of health care spending in endemic regions like Asia. In 1997 it accounted for 3.2% of South Korea's total health care expenditures and resulted in $696 million in direct costs. A large majority of that sum was spent on treating disease symptoms and complications. Chronic hepatitis B infections are not as endemic in the United States, but accounted for $357 million in hospitalization costs in the year 1990. That number grew to $1.5 billion in 2003, but remained stable as of 2006, which may be attributable to the introduction of effective drug therapies and vaccination campaigns. People infected with chronic hepatitis C tend to be frequent users of the health care system globally. It has been estimated that a person infected with hepatitis C in the United States will result in a monthly cost of $691. That number nearly doubles to $1,227 for people with compensated (stable) cirrhosis, while the monthly cost of people with decompensated (worsening) cirrhosis is almost five times as large at $3,682. The wide-ranging effects of hepatitis make it difficult to estimate indirect costs, but studies have speculated that the total cost is $6.5 billion annually in the United States. In Canada, 56% of HCV related costs are attributable to cirrhosis and total expenditures related to the virus are expected to peak at CAD$396 million in the year 2032.2003 Monaca outbreak

The largest outbreak of hepatitis A virus in United States history occurred among people who ate at a now-defunct Mexican food restaurant located in Monaca, Pennsylvania in late 2003. Over 550 people who visited the restaurant between September and October 2003 were infected with the virus, three of whom died as a direct result. The outbreak was brought to the attention of health officials when local emergency medicine physicians noticed a significant increase in cases of hepatitis A in the county. After conducting its investigation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC attributed the source of the outbreak to the use of contaminated raw Scallion, green onion. The restaurant was purchasing its green onion stock from farms in Mexico at the time. It is believed that the green onions may have been contaminated through the use of contaminated water for crop irrigation, rinsing, or icing or by handling of the vegetables by infected people. Green onion had caused similar outbreaks of hepatitis A in the southern United States prior to this, but not to the same magnitude. The CDC believes that the restaurant's use of a large communal bucket for chopped raw green onion allowed non-contaminated plants to be mixed with contaminated ones, increasing the number of vectors of infection and amplifying the outbreak. The restaurant was closed once it was discovered to be the source, and over 9,000 people were given hepatitis A Antibody, immune globulin because they had either eaten at the restaurant or had been in close contact with someone who had.Special populations

HIV co-infection

Persons infected with HIV have a particularly high burden of Hepatitis C and HIV coinfection, HIV-HCV co-infection. In a recent study by the World Health Organization, WHO, the likelihood of being infected with hepatitis C virus was six times greater in those who also had HIV. The prevalence of HIV-HCV co-infection worldwide was estimated to be 6.2% representing more than 2.2 million people. Intravenous drug use was an independent risk factor for HCV infection. In the WHO study, the prevalence of HIV-HCV co-infection was markedly higher at 82.4% in those who injected drugs compared to the general population (2.4%). In a study of HIV-HCV co-infection among HIV positive men who have sex with men (MSM), the overall prevalence of anti-hepatitis C antibodies was estimated to be 8.1% and increased to 40% among HIV positive MSM who also injected drugs.Pregnancy

Hepatitis B

Vertically transmitted infection, Vertical transmission is a significant contributor of new hepatitis B virus, HBV cases each year, with 35–50% of transmission from mother to neonate in endemic countries. Vertical transmission occurs largely via a neonate's exposure to maternal blood and vaginal secretions during birth. While the risk of progression to chronic infection is approximately 5% among adults who contract the virus, it is as high as 95% among neonates subject to vertical transmission. The risk of viral transmission is approximately 10–20% when maternal blood is positive for HBsAg, and up to 90% when also positive for HBeAg. Given the high risk of perinatal transmission, the Centre for Disease Control, CDC recommends screening all pregnant women for HBV at their first prenatal visit. It is safe for non-immune pregnant women to receive the HBV vaccine. Based on the limited available evidence, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends antiviral therapy in pregnant women whose viral load exceeds 200,000 IU/mL. A growing body of evidence shows that antiviral therapy initiated in the third trimester significantly reduces transmission to the neonate. A systematic review of the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry database found that there was no increased risk of congenital anomalies with Tenofovir disoproxil, Tenofovir; for this reason, along with its potency and low risk of resistance, the AASLD recommends this drug. A 2010 systematic review and meta-analysis found that Lamivudine initiated early in the third trimester also significantly reduced mother-to-child transmission of HBV, without any known adverse effects. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ACOG states that the evidence available does not suggest any particular mode of delivery (i.e. Vaginal delivery, vaginal vs. Caesarean section, cesarean) is better at reducing vertical transmission in mothers with HBV. The World Health Organization, WHO and CDC recommend that neonates born to mothers with HBV should receive hepatitis B immune globulin (Hepatitis B immune globulin, HBIG) as well as the Hepatitis B vaccine, HBV vaccine within 12 hours of birth. For infants who have received HBIG and the HBV vaccine, breastfeeding is safe.Hepatitis C

Estimates of the rate of hepatitis C virus, HCV vertical transmission range from 2–8%; a 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis found the risk to be 5.8% in HCV-positive, HIV-negative women. The same study found the risk of vertical transmission to be 10.8% in HCV-positive, HIV-positive women. Other studies have found the risk of vertical transmission to be as high as 44% among HIV-positive women. The risk of vertical transmission is higher when the virus is detectable in the mother's blood. Evidence does not indicate that mode of delivery (i.e. vaginal vs. cesarean) has an effect on vertical transmission. For women who are HCV-positive and HIV-negative, breastfeeding is safe. CDC guidelines suggest avoiding it if a woman's nipples are cracked or bleeding to reduce the risk of transmission.Hepatitis E

Pregnant women who contract Hepatitis E virus, HEV are at significant risk of developing fulminant hepatitis with maternal mortality rates as high as 20–30%, most commonly in the third trimester . A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 studies that included 3968 people found maternal Case fatality rate, case-fatality rates (CFR) of 20.8% and fetal CFR of 34.2%; among women who developed fulminant hepatic failure, CFR was 61.2%.See also

* World Hepatitis DayReferences

External links

WHO fact sheet of hepatitis

Viral Hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control

{{Authority control Hepatitis, Inflammations Healthcare-associated infections Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate Wikipedia infectious disease articles ready to translate Viral diseases Diseases of liver