Henry Littlejohn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Henry Duncan Littlejohn MD LLD FRCSE (8 May 1826 – 30 September 1914) was a Scottish surgeon,

Littlejohn was elected president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1875. From 1883 to 1885 he served as president of the Edinburgh Medico-Chirurgical Society. He received an honorary LLD from the University of Edinburgh in 1893. In the same year, he became president of the Royal Institute of Public Health.

He was knighted by

Littlejohn was elected president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1875. From 1883 to 1885 he served as president of the Edinburgh Medico-Chirurgical Society. He received an honorary LLD from the University of Edinburgh in 1893. In the same year, he became president of the Royal Institute of Public Health.

He was knighted by

forensic scientist

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and criminal ...

and public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

official. He served for 46 years as Edinburgh's first Medical Officer of Health

A medical officer of health, also known as a medical health officer, chief health officer, chief public health officer or district medical officer, is the title commonly used for the senior government official of a health department, usually at a m ...

, during which time he brought about significant improvements in the living conditions and the health of the city's inhabitants. He also served as a police surgeon and medical adviser in Scottish criminal cases.

Early life and education

Henry Littlejohn was born inEdinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

on 8 May 1826 to Isabella Duncan and Thomas Littlejohn, a master baker of 33 Leith Street.

He studied at the Perth Academy

Perth Academy is a state comprehensive secondary school in Perth, Scotland. It was founded in 1696. The institution is a non-denominational one. The school occupies ground on the side of a hill in the Viewlands area of Perth, and is within the P ...

before attending the Royal High School, Edinburgh

The Royal High School (RHS) of Edinburgh is a co-educational state school, school administered by the City of Edinburgh Council. The school was founded in 1128 and is one of the oldest schools in Scotland. It serves 1,200 pupils drawn from four ...

(1838 to 1841). He went on to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

, graduating in 1847. He became a Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located o ...

in the same year.

Medical and teaching career

From 1847 to 1848, Littlejohn worked as a house surgeon at theRoyal Infirmary of Edinburgh

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, or RIE, often (but incorrectly) known as the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, or ERI, was established in 1729 and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest v ...

. After a short period of study in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

, he returned to the Infirmary as an assistant pathologist. This was followed by a brief spell in general practice. He was admitted as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1854.

In 1856 he became a lecturer in medical jurisprudence

Medical jurisprudence or legal medicine is the branch of science and medicine involving the study and application of scientific and medical knowledge to legal problems, such as inquests, and in the field of law. As modern medicine is a legal ...

at the Edinburgh Extramural School of Medicine at Surgeons' Hall, Edinburgh.

Medical Officer of Health

In 1862, Littlejohn was appointed Edinburgh's first Medical Officer of Health. This was at a time when many of the town's inhabitants were living in squalor, in filthy overcrowded tenements, often with no water supply and with little or no sanitation. Disease was rampant. There had been two recent cholera epidemics, whiletyphoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

, diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) ce ...

were endemic.

During his first three years in the post, Littlejohn carried out a meticulous investigation into the living conditions and the state of health of the town's inhabitants. His report, published in 1865, contained 120 pages of detailed statistics, analysing conditions in over one thousand separate streets, closes and tenements. It included extensive data on the prevalence of the most common diseases as well as historical data on earlier epidemics. The report convincingly demonstrated the link between depravation, disease and mortality.

With the backing of Littlejohn's report, the Lord Provost, William Chambers, and the Town Council launched an ambitious programme of urban renewal

Urban renewal (also called urban regeneration in the United Kingdom and urban redevelopment in the United States) is a program of land redevelopment often used to address urban decay in cities. Urban renewal involves the clearing out of bligh ...

in Edinburgh. This resulted in the demolition of the worst slums and created the largely Victorian Old Town that exists today. On Littlejohn's recommendation, the council also brought in regulations governing water supply, sewage, building standards, food hygiene, waste disposal and the management of cemeteries.

In order to track and anticipate the spread of infectious diseases through the population, Littlejohn campaigned for legal powers to compel medical practitioners to notify him of all cases of the most infectious diseases. Despite opposition from doctors, a clause was added to the 1879 Edinburgh Municipal Police Act making such notification compulsory – the first legislation of its kind in Britain. Significantly, the Act placed responsibility for notification on the attending doctor rather than the householder. This measure was extended to the whole of Scotland through the 1897 Public Health (Scotland) Act.

In 1900, Littlejohn identified a link between cigarette smoking and cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bl ...

, 62 years before the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

produced a report which acknowledged such a link.

During Littlejohn's 46 years as Medical Officer of Health, the death rate in Edinburgh fell from 26 per thousand to 17 per thousand. There was a dramatic drop in outbreaks of smallpox and typhus. His introduction of compulsory notification of infectious diseases has been described as 'one of the major advances in public health of the 19th century'.

Police surgeon and forensic scientist

Littlejohn enjoyed a parallel career in forensic science and criminal investigation. In 1854, the Town Council appointed him to the part-time post of police surgeon. He went on to serve as medical adviser to theCrown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

in Scottish criminal cases, in which role he would continue for over 50 years. He acted as expert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge ...

in many criminal trials. These included three cases of child murder, the high-profile Ardlamont murder, and a case of culpable homicide resulting from a railway accident which claimed twenty lives. At the time of his retirement in 1908, the ''Scotsman'' noted that "there was no great criminal trial in the High Court in which he did not act as a Crown witness."

One of his most famous cases was that of the wife-murderer, Eugene Chantrelle

Eugene Marie Chantrelle (1834 in Nantes – 31 May 1878 in Edinburgh) was a French teacher who lived in Edinburgh and who was convicted for the murder of his wife, Elizabeth Dyer. He is claimed to be the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson's ch ...

. On the first day of 1878, Chantrelle's wife, Elizabeth, became violently ill, and died the next day. A broken gas pipe was discovered in her bedroom, and the police at first assumed that her death was the result of accidental gas poisoning. Littlejohn was not satisfied. Analysing some vomit found on her nightgown, he detected traces of opium. He ordered a full post mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

, which revealed that she had died of narcotic poisoning. Chantrelle was arrested, tried for murder, convicted and executed, mainly on Littlejohn's evidence.

Appointments and honours

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

in 1895.

Later life and family

In his later life Littlejohn lived at 24 Royal Circus in Edinburgh's Second New Town. He retired from public office on 10 March 1908, at the age of 82. His wife was Isabella Jane, daughter of H. Harvey. His son was Henry Harvey Littlejohn (1862–1927) (normally just called Harvey Littlejohn during his life but posthumously largely called Henry) who followed in his father's footsteps as a forensic scientist and medical officer and who adopted similar techniques of investigation and problem solving. Littlejohn died at his country house, Benreoch, near Arrochar,Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire ( gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann) or the County of Dumbarton is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Dunbartonshire borders P ...

, on 30 September 1914.

A strong proponent of cremation

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre ...

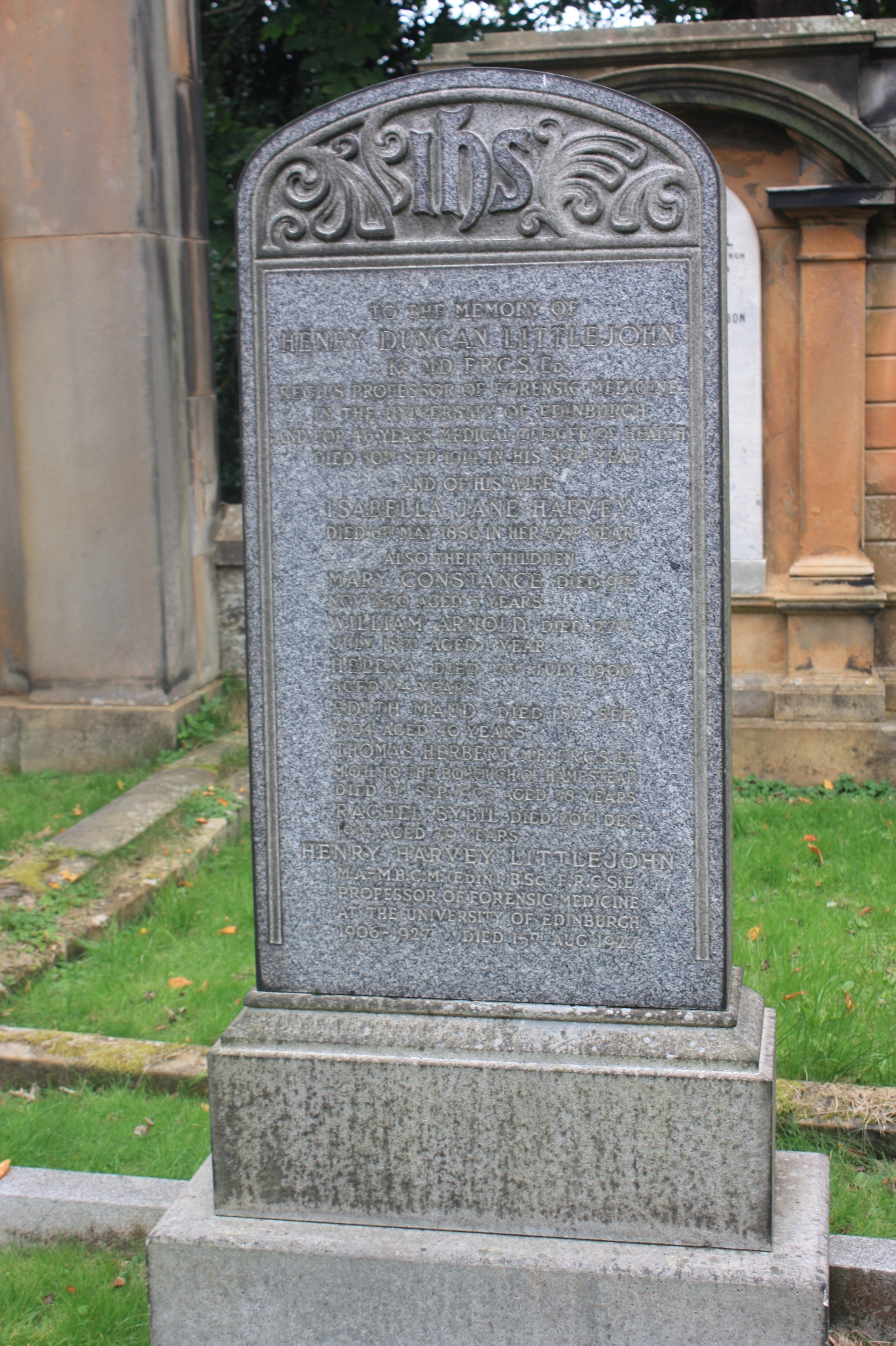

, he was cremated at the Glasgow Crematorium. His ashes were interred at the Dean Cemetery

The Dean Cemetery is a historically important Victorian cemetery north of the Dean Village, west of Edinburgh city centre, in Scotland. It lies between Queensferry Road and the Water of Leith, bounded on its east side by Dean Path and o ...

in Edinburgh. His grave is on the edge of the southern path towards the west end. He is buried with his wife and their son and daughter.

References

Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Littlejohn, Henry Duncan 1826 births 1914 deaths 19th-century Scottish people Scottish knights Knights Bachelor Civil servants from Edinburgh People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Edinburgh 19th-century Scottish medical doctors British forensic scientists British public health doctors Academics of the University of Edinburgh Medical jurisprudence Elders of the Church of Scotland Burials at the Dean Cemetery Scottish surgeons People educated at Perth Academy Medical doctors from Edinburgh Presidents of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh