Henry II Plantagenet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was

Henry was born in

Henry was born in

By the late 1140s, the active phase of the civil war was over, barring the occasional outbreak of fighting.Barlow (1999), p. 180. Many of the barons were making individual peace agreements with each other to secure their war gains and it increasingly appeared as though the English church was considering promoting a peace treaty. On Louis VII's return from the

By the late 1140s, the active phase of the civil war was over, barring the occasional outbreak of fighting.Barlow (1999), p. 180. Many of the barons were making individual peace agreements with each other to secure their war gains and it increasingly appeared as though the English church was considering promoting a peace treaty. On Louis VII's return from the  Geoffrey died in September 1151, and Henry postponed his plans to return to England, as he first needed to ensure that his succession, particularly in Anjou, was secure. At around this time, he was also probably secretly planning his marriage to

Geoffrey died in September 1151, and Henry postponed his plans to return to England, as he first needed to ensure that his succession, particularly in Anjou, was secure. At around this time, he was also probably secretly planning his marriage to

In response to Stephen's siege, Henry returned to England again at the start of 1153, braving winter storms. Bringing only a small army of mercenaries, probably paid for with borrowed money, Henry was supported in the north and east of England by the forces of Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod, and had hopes of a military victory. A delegation of senior English clergy met with Henry and his advisers at

In response to Stephen's siege, Henry returned to England again at the start of 1153, braving winter storms. Bringing only a small army of mercenaries, probably paid for with borrowed money, Henry was supported in the north and east of England by the forces of Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod, and had hopes of a military victory. A delegation of senior English clergy met with Henry and his advisers at

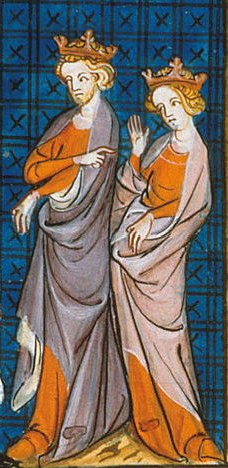

On landing in England on 8 December 1154, Henry quickly took oaths of loyalty from some of the barons and was then crowned alongside Eleanor at

On landing in England on 8 December 1154, Henry quickly took oaths of loyalty from some of the barons and was then crowned alongside Eleanor at

Henry had a problematic relationship with Louis VII of France throughout the 1150s. The two men had already clashed over Henry's succession to Normandy and the remarriage of Eleanor, and the relationship was not repaired. Louis invariably attempted to take the moral high ground in respect to Henry, capitalising on his reputation as a crusader and circulating rumours about his rival's behaviour and character. Henry had greater resources than Louis, particularly after taking England, and Louis was far less dynamic in resisting Angevin power than he had been earlier in his reign. The disputes between the two drew in other powers across the region, including

Henry had a problematic relationship with Louis VII of France throughout the 1150s. The two men had already clashed over Henry's succession to Normandy and the remarriage of Eleanor, and the relationship was not repaired. Louis invariably attempted to take the moral high ground in respect to Henry, capitalising on his reputation as a crusader and circulating rumours about his rival's behaviour and character. Henry had greater resources than Louis, particularly after taking England, and Louis was far less dynamic in resisting Angevin power than he had been earlier in his reign. The disputes between the two drew in other powers across the region, including  Henry hoped to take a similar approach to regaining control of

Henry hoped to take a similar approach to regaining control of

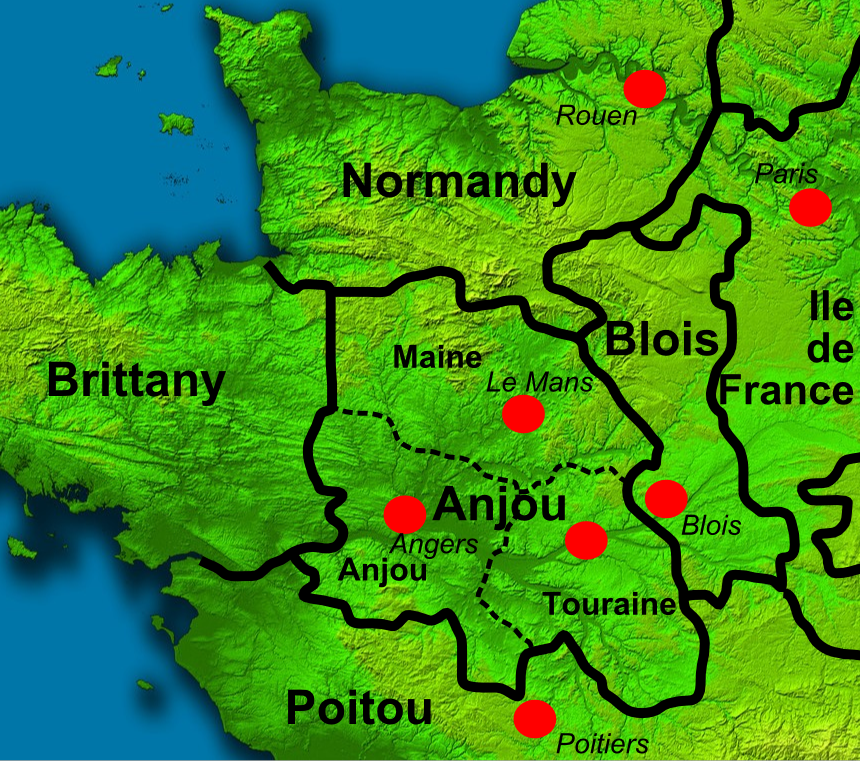

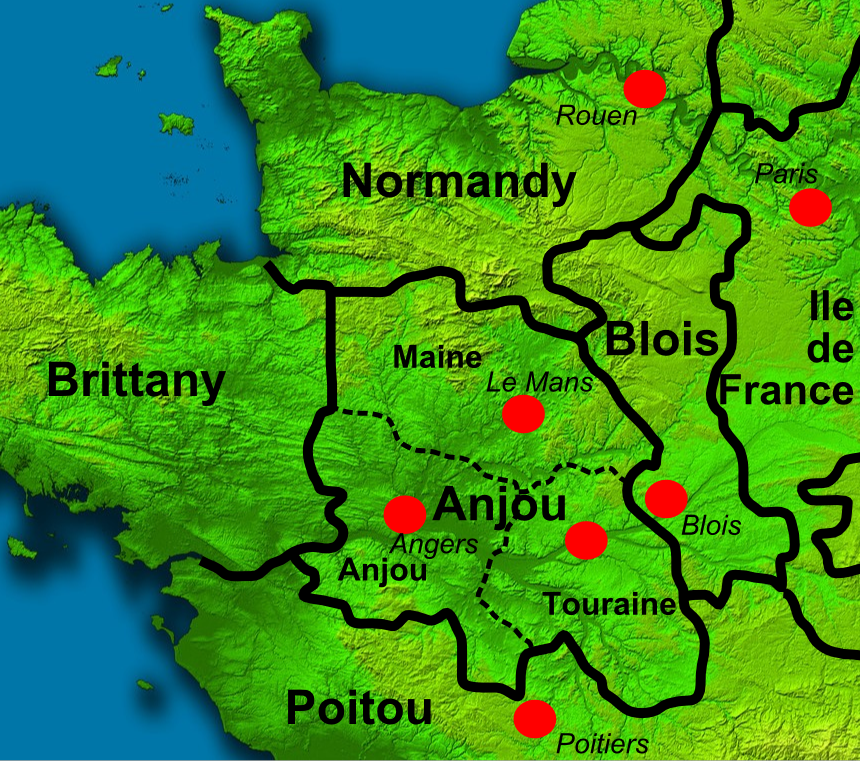

Henry controlled more of France than any ruler since the

Henry controlled more of France than any ruler since the

Henry's wealth allowed him to maintain what was probably the largest ''curia regis'', or royal court, in Europe. His court attracted huge attention from contemporary chroniclers, and typically comprised several major nobles and bishops, along with knights, domestic servants, prostitutes, clerks, horses and hunting dogs. Within the court were his officials, ''ministeriales'', his friends, ''amici'', and the ''familiares regis'', the King's informal inner circle of confidants and trusted servants. Henry's ''familiares'' were particularly important to the operation of his household and government, driving government initiatives and filling the gaps between the official structures and the King.

Henry tried to maintain a sophisticated household that combined hunting and drinking with cosmopolitan literary discussion and courtly values. Nonetheless, Henry's passion was for hunting, for which the court became famous. Henry had several preferred royal hunting lodges and apartments across his lands, and invested heavily in his royal castles, both for their practical utility as fortresses, and as symbols of royal power and prestige. The court was relatively formal in its style and language, possibly because Henry was attempting to compensate for his own sudden rise to power and relatively humble origins as the son of a count. He opposed the holding of

Henry's wealth allowed him to maintain what was probably the largest ''curia regis'', or royal court, in Europe. His court attracted huge attention from contemporary chroniclers, and typically comprised several major nobles and bishops, along with knights, domestic servants, prostitutes, clerks, horses and hunting dogs. Within the court were his officials, ''ministeriales'', his friends, ''amici'', and the ''familiares regis'', the King's informal inner circle of confidants and trusted servants. Henry's ''familiares'' were particularly important to the operation of his household and government, driving government initiatives and filling the gaps between the official structures and the King.

Henry tried to maintain a sophisticated household that combined hunting and drinking with cosmopolitan literary discussion and courtly values. Nonetheless, Henry's passion was for hunting, for which the court became famous. Henry had several preferred royal hunting lodges and apartments across his lands, and invested heavily in his royal castles, both for their practical utility as fortresses, and as symbols of royal power and prestige. The court was relatively formal in its style and language, possibly because Henry was attempting to compensate for his own sudden rise to power and relatively humble origins as the son of a count. He opposed the holding of  The Angevin Empire and court was, as historian John Gillingham describes it, "a family firm". His mother, Matilda, played an important role in his early life and exercised influence for many years later. Henry's relationship with his wife Eleanor was complex: Henry trusted Eleanor to manage England for several years after 1154, and was later content for her to govern Aquitaine; indeed, Eleanor was believed to have influence over Henry during much of their marriage. Ultimately, their relationship disintegrated and chroniclers and historians have speculated on what ultimately caused Eleanor to abandon Henry to support her older sons in the Great Revolt of 1173–74. Probable explanations include Henry's persistent interference in Aquitaine, his recognition of Raymond of Toulouse in 1173, or his harsh temper. He had several long-term mistresses, including Annabel de Balliol and

The Angevin Empire and court was, as historian John Gillingham describes it, "a family firm". His mother, Matilda, played an important role in his early life and exercised influence for many years later. Henry's relationship with his wife Eleanor was complex: Henry trusted Eleanor to manage England for several years after 1154, and was later content for her to govern Aquitaine; indeed, Eleanor was believed to have influence over Henry during much of their marriage. Ultimately, their relationship disintegrated and chroniclers and historians have speculated on what ultimately caused Eleanor to abandon Henry to support her older sons in the Great Revolt of 1173–74. Probable explanations include Henry's persistent interference in Aquitaine, his recognition of Raymond of Toulouse in 1173, or his harsh temper. He had several long-term mistresses, including Annabel de Balliol and

Henry's reign saw significant legal changes, particularly in England and Normandy. By the middle of the 12th century, England had many different ecclesiastical and civil

Henry's reign saw significant legal changes, particularly in England and Normandy. By the middle of the 12th century, England had many different ecclesiastical and civil

Henry's relationship with the Church varied considerably across his lands and over time: as with other aspects of his rule, there was no attempt to form a common ecclesiastical policy. Insofar as he had a policy, it was to generally resist papal influence, increasing his own local authority. The 12th century saw a reforming movement within the Church, advocating greater autonomy from royal authority for the clergy and more influence for the papacy. This trend had already caused tensions in England, for example when King Stephen forced

Henry's relationship with the Church varied considerably across his lands and over time: as with other aspects of his rule, there was no attempt to form a common ecclesiastical policy. Insofar as he had a policy, it was to generally resist papal influence, increasing his own local authority. The 12th century saw a reforming movement within the Church, advocating greater autonomy from royal authority for the clergy and more influence for the papacy. This trend had already caused tensions in England, for example when King Stephen forced

Henry restored many of the old financial institutions of his grandfather Henry I and undertook further, long-lasting reforms of the management of the English currency; one result was a long-term increase in the

Henry restored many of the old financial institutions of his grandfather Henry I and undertook further, long-lasting reforms of the management of the English currency; one result was a long-term increase in the

Long-running tensions between Henry and Louis VII continued during the 1160s, the French king slowly becoming more vigorous in opposing Henry's increasing power in Europe. In 1160 Louis strengthened his alliances in central France with the Count of Champagne and

Long-running tensions between Henry and Louis VII continued during the 1160s, the French king slowly becoming more vigorous in opposing Henry's increasing power in Europe. In 1160 Louis strengthened his alliances in central France with the Count of Champagne and

One of the major international events surrounding Henry during the 1160s was the Becket controversy. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theobald of Bec, died in 1161 Henry saw an opportunity to reassert his rights over the church in England. Henry appointed

One of the major international events surrounding Henry during the 1160s was the Becket controversy. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theobald of Bec, died in 1161 Henry saw an opportunity to reassert his rights over the church in England. Henry appointed

In the mid-12th century Ireland was ruled by local

In the mid-12th century Ireland was ruled by local

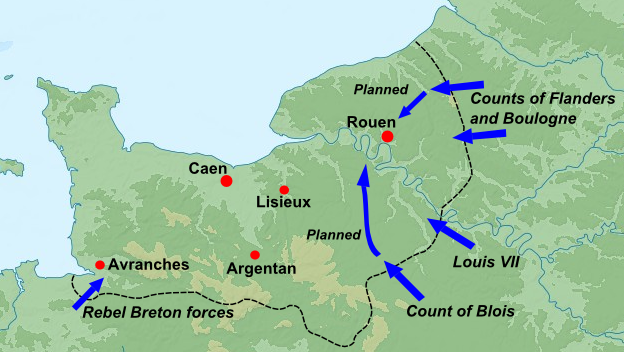

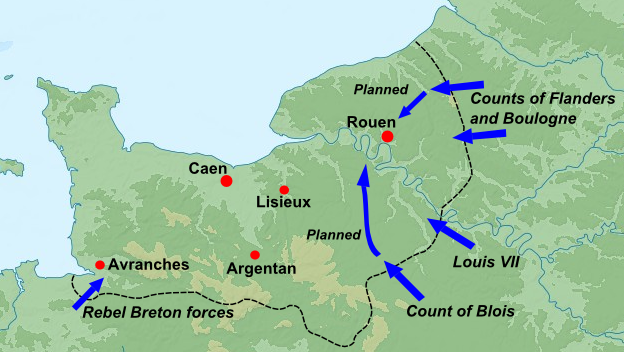

In 1173 Henry faced the Great Revolt, an uprising by his eldest sons and rebellious barons, supported by France, Scotland and Flanders. Several grievances underpinned the revolt. Young Henry was unhappy that, despite the title of king, in practice he made no real decisions and his father kept him chronically short of money. He had also been very attached to Thomas Becket, his former tutor, and may have held his father responsible for Becket's death. Geoffrey faced similar difficulties; Duke Conan of Brittany had died in 1171, but Geoffrey and Constance were still unmarried, leaving Geoffrey in limbo without his own lands. Richard was encouraged to join the revolt as well by Eleanor, whose relationship with Henry had disintegrated. Meanwhile, local barons unhappy with Henry's rule saw opportunities to recover traditional powers and influence by allying themselves with his sons.

The final straw was Henry's decision to give his youngest son John three major castles belonging to Young Henry, who first protested and then fled to Paris, followed by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey; Eleanor attempted to join them but was captured by Henry's forces in November. Louis supported Young Henry and war became imminent. Young Henry wrote to the pope, complaining about his father's behaviour, and began to acquire allies, including King William of Scotland and the Counts of Boulogne, Flanders and Blois—all of whom were promised lands if Young Henry won. Major baronial revolts broke out in England, Brittany, Maine, Poitou and

In 1173 Henry faced the Great Revolt, an uprising by his eldest sons and rebellious barons, supported by France, Scotland and Flanders. Several grievances underpinned the revolt. Young Henry was unhappy that, despite the title of king, in practice he made no real decisions and his father kept him chronically short of money. He had also been very attached to Thomas Becket, his former tutor, and may have held his father responsible for Becket's death. Geoffrey faced similar difficulties; Duke Conan of Brittany had died in 1171, but Geoffrey and Constance were still unmarried, leaving Geoffrey in limbo without his own lands. Richard was encouraged to join the revolt as well by Eleanor, whose relationship with Henry had disintegrated. Meanwhile, local barons unhappy with Henry's rule saw opportunities to recover traditional powers and influence by allying themselves with his sons.

The final straw was Henry's decision to give his youngest son John three major castles belonging to Young Henry, who first protested and then fled to Paris, followed by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey; Eleanor attempted to join them but was captured by Henry's forces in November. Louis supported Young Henry and war became imminent. Young Henry wrote to the pope, complaining about his father's behaviour, and began to acquire allies, including King William of Scotland and the Counts of Boulogne, Flanders and Blois—all of whom were promised lands if Young Henry won. Major baronial revolts broke out in England, Brittany, Maine, Poitou and

In the aftermath of the Great Revolt, Henry held negotiations at Montlouis, offering a lenient peace on the basis of the pre-war status quo. Henry and Young Henry swore not to take revenge on each other's followers; Young Henry agreed to the transfer of the disputed castles to John, but in exchange the elder Henry agreed to give the younger Henry two castles in Normandy and 15,000

In the aftermath of the Great Revolt, Henry held negotiations at Montlouis, offering a lenient peace on the basis of the pre-war status quo. Henry and Young Henry swore not to take revenge on each other's followers; Young Henry agreed to the transfer of the disputed castles to John, but in exchange the elder Henry agreed to give the younger Henry two castles in Normandy and 15,000

Henry's relationship with his two surviving heirs was fraught. The King had great affection for his youngest son John, but showed little warmth towards Richard and indeed seems to have borne him a grudge after their argument in 1184. The bickering and simmering tensions between Henry and Richard were cleverly exploited by the new French King,

Henry's relationship with his two surviving heirs was fraught. The King had great affection for his youngest son John, but showed little warmth towards Richard and indeed seems to have borne him a grudge after their argument in 1184. The bickering and simmering tensions between Henry and Richard were cleverly exploited by the new French King,

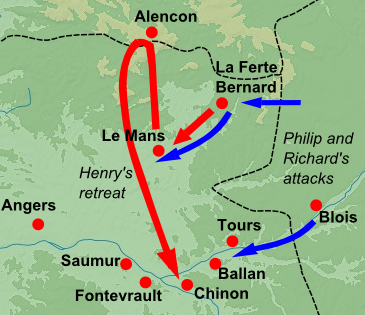

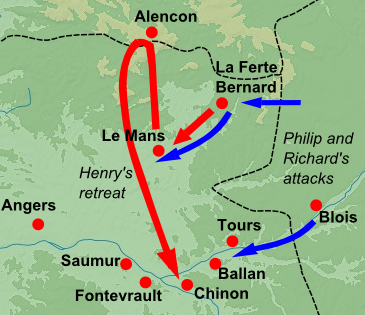

The relationship between Henry and Richard finally descended into violence shortly before Henry's death. Philip held a peace conference in November 1188, making a public offer of a generous long-term peace settlement with Henry, conceding to his various territorial demands, if Henry would finally marry Richard and Alys and announce Richard as his recognised heir.Warren (2000), p. 621. Henry refused the proposal, whereupon Richard himself spoke up, demanding to be recognised as Henry's successor. Henry remained silent and Richard then publicly changed sides at the conference and gave formal homage to Philip in front of the assembled nobles.

The papacy intervened once again to try to produce a last-minute peace deal, resulting in a fresh conference at

The relationship between Henry and Richard finally descended into violence shortly before Henry's death. Philip held a peace conference in November 1188, making a public offer of a generous long-term peace settlement with Henry, conceding to his various territorial demands, if Henry would finally marry Richard and Alys and announce Richard as his recognised heir.Warren (2000), p. 621. Henry refused the proposal, whereupon Richard himself spoke up, demanding to be recognised as Henry's successor. Henry remained silent and Richard then publicly changed sides at the conference and gave formal homage to Philip in front of the assembled nobles.

The papacy intervened once again to try to produce a last-minute peace deal, resulting in a fresh conference at

In the immediate aftermath of Henry's death, Richard successfully claimed his father's lands; he later left on the

In the immediate aftermath of Henry's death, Richard successfully claimed his father's lands; he later left on the

Henry II appears as a character in several modern plays and films. Henry is depicted in the play ''

Henry II appears as a character in several modern plays and films. Henry is depicted in the play ''

Medieval Sourcebook: Angevin EnglandHenry II

at the Royal Family website

Henry II

from the online ''

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin king of England

The Angevins (; "from Anjou") were a royal house of French origin that ruled England in the 12th and early 13th centuries; its monarchs were Henry II, Richard I and John. In the 10 years from 1144, two successive counts of Anjou in France, Ge ...

. King Louis VII of France

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

made him Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western Kingdom of France, France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles the Simple, Charles III in ...

in 1150. Henry became Count of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by Charles the Bald in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the title of Count of Anjou. The Robertians ...

and Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

upon the death of his father, Count Geoffrey V

Geoffrey V (24 August 1113 – 7 September 1151), called the Handsome, the Fair (french: link=no, le Bel) or Plantagenet, was the count of Anjou, Touraine and Maine by inheritance from 1129, and also Duke of Normandy by conquest from 1144. His ...

, in 1151. His marriage in 1152 to Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II, and Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right from ...

, former spouse of Louis VII, made him Duke of Aquitaine

The Duke of Aquitaine ( oc, Duc d'Aquitània, french: Duc d'Aquitaine, ) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As succe ...

. He became Count of Nantes The counts of Nantes were originally the Frankish rulers of the Nantais under the Carolingians and eventually a capital city of the Duchy of Brittany. Their county served as a march against the Bretons of the Vannetais. Carolingian rulers would so ...

by treaty in 1158. Before he was 40, he controlled England; large parts of Wales; the eastern half of Ireland; and the western half of France, an area that was later called the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and W ...

. At various times, Henry also partially controlled Scotland and the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany ( br, Dugelezh Breizh, ; french: Duché de Bretagne) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of Europe, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

.

Henry became politically involved by the age of 14 in the efforts of his mother Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

, daughter of Henry I of England

Henry I (c. 1068 – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in ...

, to claim the English throne, then occupied by Stephen of Blois

Stephen (1092 or 1096 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois, was King of England from 22 December 1135 to his death in 1154. He was Count of Boulogne ''jure uxoris'' from 1125 until 1147 and Duke of Normandy from 1135 unt ...

. Stephen agreed to a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

after Henry's military expedition to England in 1153, and Henry inherited the kingdom on Stephen's death a year later. Henry was an energetic and ruthless ruler, driven by a desire to restore the lands and privileges of his grandfather Henry I. During the early years of his reign the younger Henry restored the royal administration in England, re-established hegemony over Wales and gained full control over his lands in Anjou, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

and Touraine

Touraine (; ) is one of the traditional provinces of France. Its capital was Tours. During the political reorganization of French territory in 1790, Touraine was divided between the departments of Indre-et-Loire, :Loir-et-Cher, Indre and Vie ...

. Henry's desire to reform the relationship with the Church led to conflict with his former friend Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

. This controversy lasted for much of the 1160s and resulted in Becket's murder in 1170. Henry soon came into conflict with Louis VII, and the two rulers fought what has been termed a "cold war

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

" over several decades. Henry expanded his empire at Louis's expense, taking Brittany and pushing east into central France and south into Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Par ...

; despite numerous peace conferences and treaties, no lasting agreement was reached.

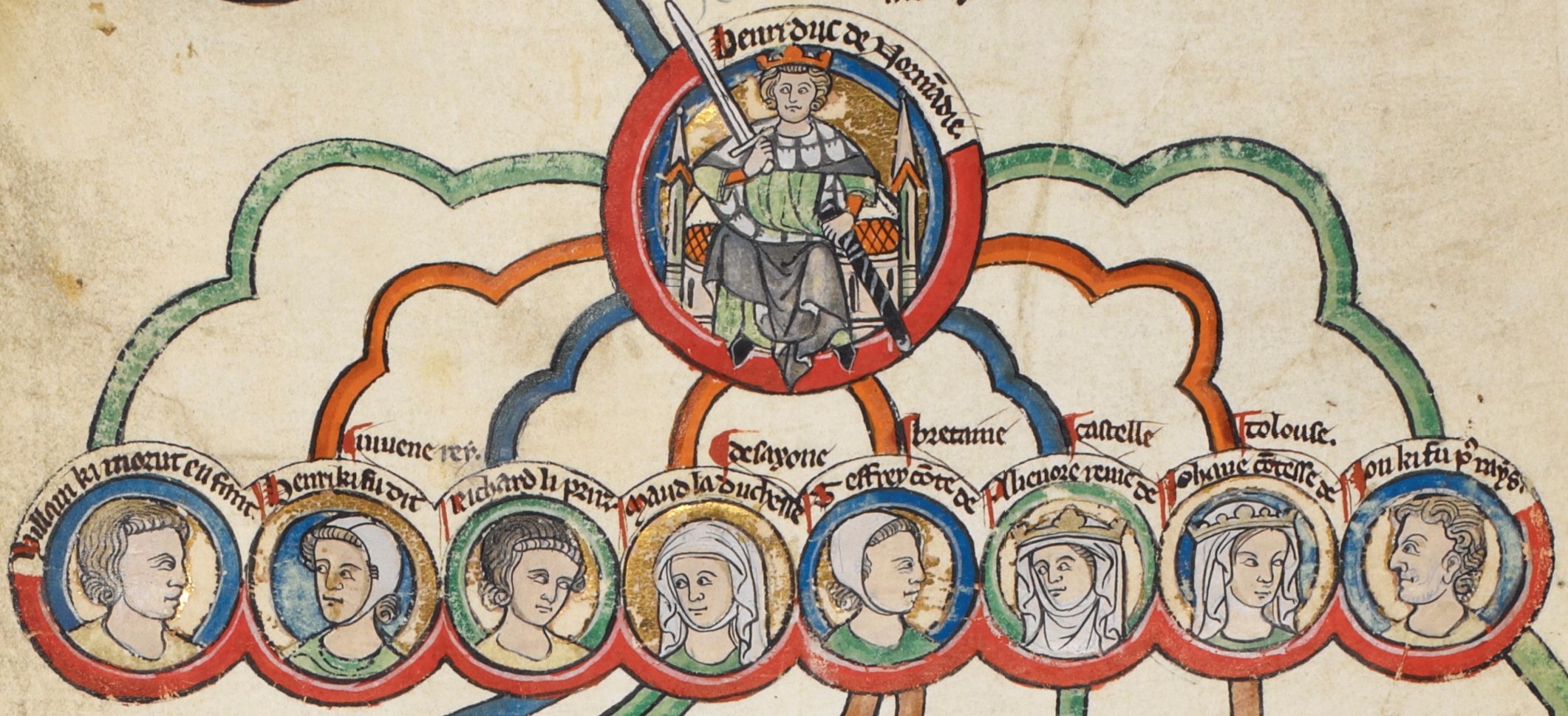

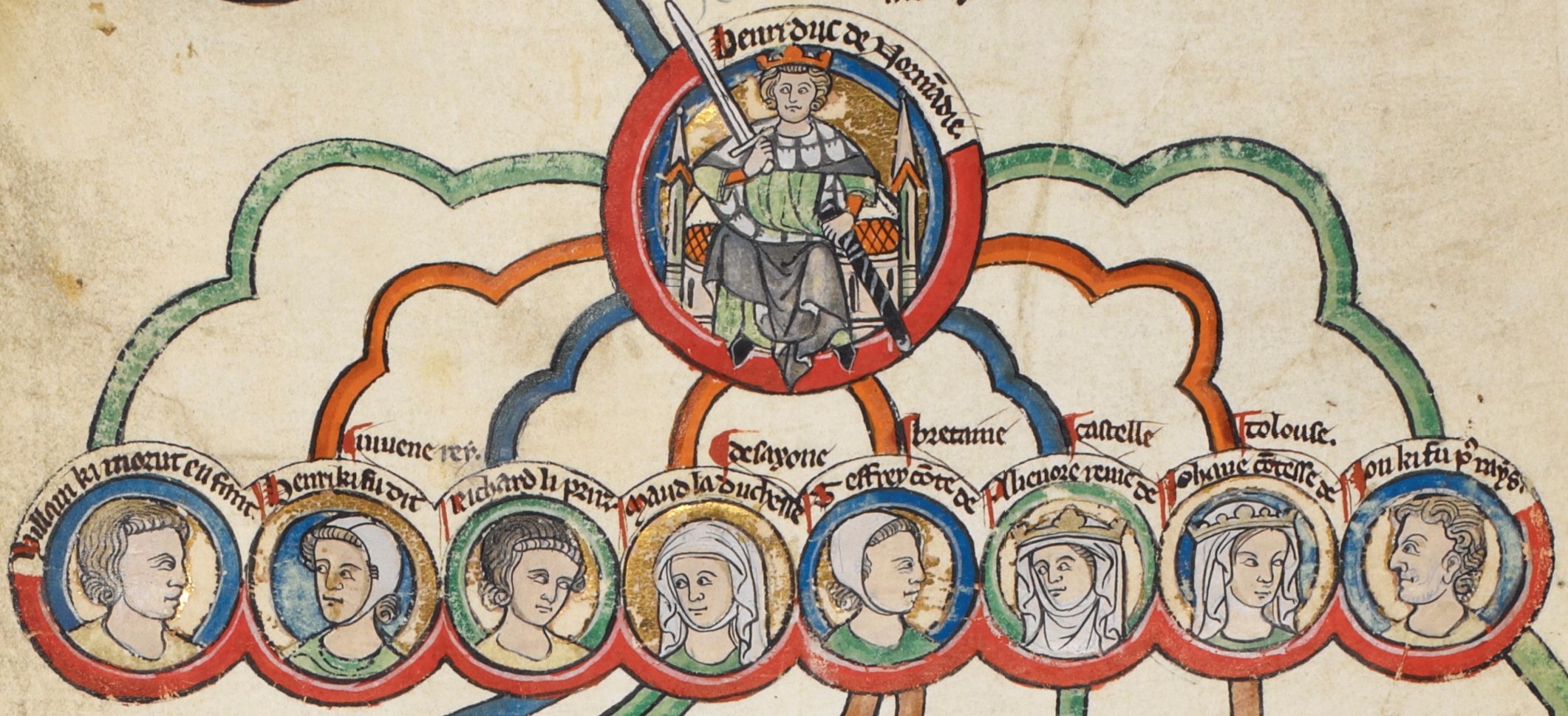

Henry and Eleanor had eight children—three daughters and five sons. Three of his sons would be king, though Henry the Young King

Henry the Young King (28 February 1155 – 11 June 1183) was the eldest son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine to survive childhood. Beginning in 1170, he was titular King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Mai ...

was named his father's co-ruler rather than a stand-alone king. As the sons grew up, tensions over the future inheritance of the empire began to emerge, encouraged by Louis and his son King Philip II. In 1173 Henry's heir apparent, "Young Henry", rebelled in protest; he was joined by his brothers Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

and Geoffrey and by their mother, Eleanor. France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

, Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

, and Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

allied themselves with the rebels. The Great Revolt was only defeated by Henry's vigorous military action and talented local commanders, many of them "new men

New men is a term referring to various groups of the socially upwardly mobile in England during the House of Lancaster, House of York and Tudor periods. The term may refer to the new aristocracy, or the enriched gentry. It is used by some h ...

" appointed for their loyalty and administrative skills. Young Henry and Geoffrey revolted again in 1183, resulting in Young Henry's death. The Norman invasion of Ireland

The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland took place during the late 12th century, when Anglo-Normans gradually conquered and acquired large swathes of land from the Irish, over which the kings of England then claimed sovereignty, all allegedly sanc ...

provided lands for his youngest son John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, but Henry struggled to find ways to satisfy all his sons' desires for land and immediate power. By 1189, Young Henry and Geoffrey were dead, and Philip successfully played on Richard's fears that Henry II would make John king, leading to a final rebellion. Decisively defeated by Philip and Richard and suffering from a bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

ulcer

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughing o ...

, Henry retreated to Chinon Castle in Anjou. He died soon afterwards and was succeeded by Richard.

Henry's empire quickly collapsed during the reign of his son John (who succeeded Richard in 1199), but many of the changes Henry introduced during his long rule had long-term consequences. Henry's legal changes are generally considered to have laid the basis for the English Common Law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, bee ...

, while his intervention in Brittany, Wales, and Scotland shaped the development of their societies and governmental systems. Historical interpretations of Henry's reign have changed considerably over time. Contemporary chroniclers such as Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and English historians in the Middle Ages, historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and w ...

and William of Newburgh

William of Newburgh or Newbury ( la, Guilelmus Neubrigensis, ''Wilhelmus Neubrigensis'', or ''Willelmus de Novoburgo''. 1136 – 1198), also known as William Parvus, was a 12th-century English historian and Augustinian canon of Anglo-Saxon des ...

, though sometimes unfavorable, generally lauded his achievements, describing him as "our Alexander of the West" and an "excellent and beneficent prince" respectively. In the 18th century, scholars argued that Henry was a driving force in the creation of a genuinely English monarchy and, ultimately, a unified Britain with David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

going so far as to characterize Henry as "the greatest prince of his time for wisdom, virtue, and abilities, and the most powerful in extent of dominion of all those who had ever filled the throne of England". During the Victorian expansion of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, historians were keenly interested in the formation of Henry's own empire, but they also expressed concern over his private life and treatment of Becket. Late 20th-century historians have combined British and French historical accounts of Henry, challenging earlier Anglocentric interpretations of his reign. Nevertheless, Henry has drawn continual interest from academic and popular historians, including Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, who described Henry as a great king and the first great English lawgiver, whose reign left a deep mark on English institutions.

Early years (1133–1149)

Henry was born in

Henry was born in Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

at Le Mans

Le Mans (, ) is a city in northwestern France on the Sarthe River where it meets the Huisne. Traditionally the capital of the province of Maine, it is now the capital of the Sarthe department and the seat of the Roman Catholic diocese of Le Man ...

on 5 March 1133, the eldest child of the Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

and her second husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou

Geoffrey V (24 August 1113 – 7 September 1151), called the Handsome, the Fair (french: link=no, le Bel) or Plantagenet, was the count of Anjou, Count of Tours, Touraine and Count of Maine, Maine by inheritance from 1129, and also Duke of Nor ...

. The French county of Anjou

The County of Anjou (, ; ; la, Andegavia) was a small French county that was the predecessor to the better-known Duchy of Anjou. Its capital was Angers, and its area was roughly co-extensive with the diocese of Angers. Anjou was bordered by Brit ...

was formed in the 10th century and the Angevin

Angevin or House of Anjou may refer to:

*County of Anjou or Duchy of Anjou, a historical county, and later Duchy, in France

**Angevin (language), the traditional langue d'oïl spoken in Anjou

**Counts and Dukes of Anjou

* House of Ingelger, a Frank ...

rulers attempted for several centuries to extend their influence and power across France through careful marriages and political alliances. In theory, the county answered to the French king, but royal power over Anjou weakened during the 11th century and the county became largely autonomous.

Henry's mother was the eldest daughter of Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the No ...

, King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

and Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western Kingdom of France, France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles the Simple, Charles III in ...

. She was born into a powerful ruling class of Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Fran ...

, who traditionally owned extensive estates in both England and Normandy, and her first husband had been the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V

Henry V (german: Heinrich V.; probably 11 August 1081 or 1086 – 23 May 1125, in Utrecht) was King of Germany (from 1099 to 1125) and Holy Roman Emperor (from 1111 to 1125), as the fourth and last ruler of the Salian dynasty. He was made co-ru ...

. After her father's death in 1135, Matilda hoped to claim the English throne, but instead her cousin Stephen of Blois

Stephen (1092 or 1096 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois, was King of England from 22 December 1135 to his death in 1154. He was Count of Boulogne ''jure uxoris'' from 1125 until 1147 and Duke of Normandy from 1135 unt ...

was crowned king and recognised as the Duke of Normandy, resulting in civil war between their rival supporters. Geoffrey took advantage of the confusion to attack the Duchy of Normandy but played no direct role in the English conflict, leaving this to Matilda and her half-brother, Robert, Earl of Gloucester

Robert FitzRoy, 1st Earl of Gloucester (c. 1090 – 31 October 1147 David Crouch, 'Robert, first earl of Gloucester (b. c. 1090, d. 1147)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 200Retrieved ...

. The war, termed the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legiti ...

by Victorian historians, dragged on and degenerated into stalemate.

Henry most likely spent some of his earliest years in his mother's household, and accompanied Matilda to Normandy in the late 1130s. Henry's later childhood, probably from the age of seven, was spent in Anjou, where he was educated by Peter of Saintes, a noted grammarian

Grammarian may refer to:

* Alexandrine grammarians, philologists and textual scholars in Hellenistic Alexandria in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE

* Biblical grammarians, scholars who study the Bible and the Hebrew language

* Grammarian (Greco-Roman ...

of the day. In late 1142, Geoffrey decided to send the nine-year-old to Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, the centre of Angevin opposition to Stephen in the south-west of England, accompanied by Robert of Gloucester.King (2010), p. 185. Although having children educated in relatives' households was common among noblemen of the period, sending Henry to England also had political benefits, as Geoffrey was coming under criticism for refusing to join the war in England. For about a year, Henry lived alongside Roger of Worcester

Roger of Worcester (c. 1118 – 9 or 10 August 1179) was Bishop of Worcester from 1163 to 1179. He had a major role in the controversy between Henry II of England, who was Roger's cousin, and Archbishop Thomas Becket.Cheney ''Roger, Bishop of ...

, one of Robert's sons, and was instructed by a '' magister'', Master Matthew; Robert's household was known for its education and learning. The canons of St Augustine's in Bristol also helped in Henry's education, and he remembered them with affection in later years. Henry returned to Anjou in either 1143 or 1144, resuming his education under William of Conches

William of Conches (c. 1090/1091 – c. 1155/1170s) was a French scholastic philosopher who sought to expand the bounds of Christian humanism by studying secular works of the classics and fostering empirical science. He was a prominent membe ...

, another famous academic.

Henry returned to England in 1147, when he was fourteen.Warren (2000), p. 33. Taking his immediate household and a few mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

, he left Normandy and landed in England, striking into Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

. Despite initially causing considerable panic, the expedition had little success, and Henry found himself unable to pay his forces and therefore unable to return to Normandy. Neither his mother nor his uncle was prepared to support him, implying that they had not approved of the expedition in the first place. Surprisingly, Henry instead turned to King Stephen, who paid the outstanding wages and thereby allowed Henry to retire gracefully. Stephen's reasons for doing so are unclear. One potential explanation is his general courtesy to a member of his extended family; another is that he was starting to consider how to end the war peacefully, and saw this as a way of building a relationship with Henry. Henry intervened once again in 1149, commencing what is often termed the Henrician phase of the civil war. This time, Henry planned to form a northern alliance with King David I of Scotland

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim (Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcolm ...

, Henry's great-uncle, and Ranulf of Chester, a powerful regional leader who controlled most of the north-west of England. Under this alliance, Henry and Ranulf agreed to attack York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, probably with help from the Scots. The planned attack disintegrated after Stephen marched rapidly north to York, and Henry returned to Normandy.Davis, p. 107; King (2010), p. 255.

Appearance and personality

Henry was said by chroniclers to be good-looking, red-haired, freckled, with a large head; he had a short, stocky body and wasbow-legged

Genu varum (also called bow-leggedness, bandiness, bandy-leg, and tibia vara) is a varus deformity marked by (outward) bowing at the knee, which means that the lower leg is angled inward ( medially) in relation to the thigh's axis, giving the ...

from riding. Often he was scruffily dressed. Henry was neither as reserved as his mother nor as charming as his father, but he was famous for his energy and drive. He was ruthless but not vindictive. He was also infamous for his piercing stare, bullying, bursts of temper and, on occasion, his sullen refusal to speak at all. Some of these outbursts may have been theatrical and for effect.Vincent (2007b), pp. 311–312. Henry was said to have understood a wide range of languages, including English, but spoke only Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

. In his youth Henry enjoyed warfare, hunting and other adventurous pursuits; as the years went by he put increasing energy into judicial

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudication, adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and app ...

and administrative affairs and became more cautious, but throughout his life he was energetic and frequently impulsive. Despite his surges of anger, he was not normally fiery or overbearing; he was witty in conversation and eloquent in argument with an intellectually bent mind and an astonishing memory, and much preferred the solitude of hunting or retiring to his chamber with a book than the entertainments of tournaments or troubadours. Henry also had concern for ordinary people, ordaining early in his reign that those shipwrecked should be well-treated and prescribing heavy penalties for anyone who plundered their goods. Ralph of Diceto

Ralph de Diceto (or Ralph of Diss; c. 1120c. 1202) was archdeacon of Middlesex, dean of St Paul's Cathedral (from c. 1180), and author of two chronicles, the ''Abbreviationes chronicorum'' and the ''Ymagines historiarum''.

Early career

Ralph is ...

records that when a famine struck Anjou and Maine in 1176, Henry emptied his private stores to relieve distress among the poor.

Henry had a passionate desire to rebuild his control of the territories that his grandfather, HenryI, had once governed.Gillingham (1984), p. 21. He may well have been influenced by his mother in this regard, as Matilda also had a strong sense of ancestral rights and privileges.Martinson, p. 6. Henry took back territories, regained estates, and re-established influence over the smaller lords that had once provided what historian John Gillingham

John Bennett Gillingham (born 3 August 1940) is Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at the London School of Economics and Political Science. On 19 July 2007 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

Gillingham is renowned as an expert on ...

describes as a "protective ring" around his core territories. He was probably the first king of England to use a heraldic

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known branc ...

design: a signet ring

A seal is a device for making an impression in wax, clay, paper, or some other medium, including an embossment on paper, and is also the impression thus made. The original purpose was to authenticate a document, or to prevent interference with a ...

with either a leopard or a lion engraved on it. The design would be altered in later generations to form the Royal Arms of England

The royal arms of England are the Coat of arms, arms first adopted in a fixed form at the start of the age of heraldry (circa 1200) as Armorial of the House of Plantagenet, personal arms by the House of Plantagenet, Plantagenet kings who ruled ...

.

Early reign (1150–1162)

Acquisition of Normandy, Anjou, and Aquitaine

By the late 1140s, the active phase of the civil war was over, barring the occasional outbreak of fighting.Barlow (1999), p. 180. Many of the barons were making individual peace agreements with each other to secure their war gains and it increasingly appeared as though the English church was considering promoting a peace treaty. On Louis VII's return from the

By the late 1140s, the active phase of the civil war was over, barring the occasional outbreak of fighting.Barlow (1999), p. 180. Many of the barons were making individual peace agreements with each other to secure their war gains and it increasingly appeared as though the English church was considering promoting a peace treaty. On Louis VII's return from the Second Crusade

The Second Crusade (1145–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusa ...

in 1149, he became concerned about the growth of Geoffrey's power and the potential threat to his own possessions, especially if Henry could acquire the English crown. In 1150, Geoffrey made Henry the Duke of Normandy and Louis responded by putting forward King Stephen's son Eustace

Eustace, also rendered Eustis, ( ) is the rendition in English of two phonetically similar Greek given names:

*Εὔσταχυς (''Eústachys'') meaning "fruitful", "fecund"; literally "abundant in grain"; its Latin equivalents are ''Fæcundus/Fe ...

as the rightful heir to the duchy and launching a military campaign to remove Henry from the province. Henry's father advised him to come to terms with Louis and peace was made between them in August 1151 after mediation by Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist. ( la, Bernardus Claraevallensis; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templars, and a major leader in the reformation of the Benedictine Order through ...

.Warren (2000), p. 42. Under the settlement Henry did homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to Louis for Normandy, accepting Louis as his feudal lord, and gave him the disputed lands of the Norman Vexin

Vexin () is an historical county of northwestern France. It covers a verdant plateau on the right bank (north) of the Seine running roughly east to west between Pontoise and Romilly-sur-Andelle (about 20 km from Rouen), and north to south ...

; in return, Louis recognised him as duke.

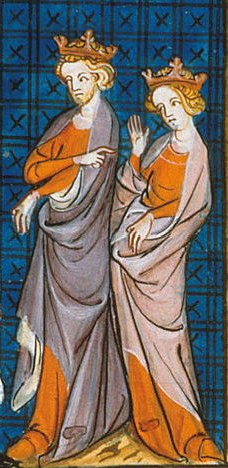

Geoffrey died in September 1151, and Henry postponed his plans to return to England, as he first needed to ensure that his succession, particularly in Anjou, was secure. At around this time, he was also probably secretly planning his marriage to

Geoffrey died in September 1151, and Henry postponed his plans to return to England, as he first needed to ensure that his succession, particularly in Anjou, was secure. At around this time, he was also probably secretly planning his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II, and Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right from ...

, then still the wife of Louis. Eleanor was the Duchess of Aquitaine, a land in the south of France, and was considered beautiful, lively and controversial, but had not borne Louis any sons. Louis had the marriage annulled

Annulment is a legal procedure within secular and religious legal systems for declaring a marriage null and void. Unlike divorce, it is usually retroactive, meaning that an annulled marriage is considered to be invalid from the beginning almost ...

and Henry married Eleanor eight weeks later on 18 May. The marriage instantly reignited Henry's tensions with Louis: it was considered an insult, it ran counter to feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

practice, as Henry had "stolen" Louis' wife, and it threatened the inheritance of Louis and Eleanor's two daughters, Marie

Marie may refer to:

People Name

* Marie (given name)

* Marie (Japanese given name)

* Marie (murder victim), girl who was killed in Florida after being pushed in front of a moving vehicle in 1973

* Marie (died 1759), an enslaved Cree person in Tro ...

and Alix

''Alix'', or ''The Adventures of Alix'', is a Franco-Belgian comics series drawn in the ligne claire style by Jacques Martin. The stories revolve around a young Gallo-Roman man named Alix in the late Roman Republic. Although the series is re ...

, who might otherwise have had claims to Aquitaine on Eleanor's death. With his new lands, Henry now possessed a much larger proportion of France than Louis. Louis organised a coalition against Henry, including Stephen, Eustace, Henry I, Count of Champagne

Henry I (December 1127 – March 16, 1181), known as the Liberal, was count of Champagne from 1152 to 1181. He was the eldest son of Count Theobald II of Champagne, who was also count of Blois, and his wife, Matilda of Carinthia.

Biography

Henry ...

, and Robert, Count of Perche The county of Perche was a medieval county lying between Normandy and Maine (province), Maine.

It was held by an independent line of counts until 1226. One of these, Geoffroy V, would have been a leader of the Fourth Crusade had he not died before ...

. Louis's alliance was joined by Henry's younger brother, Geoffrey, who rose in revolt, claiming that Henry had dispossessed him of his inheritance. Their father's plans for the inheritance of his lands had been ambiguous, making the veracity of Geoffrey's claims hard to assess. Contemporaneous accounts suggest he left the main castles in Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

to Geoffrey, implying that he may have intended Henry to retain Normandy and Anjou but not Poitou.Warren (2000), p. 46.

Fighting immediately broke out again along the Normandy borders, where Henry of Champagne and Robert captured the town of Neufmarché-sur-Epte. Louis's forces moved to attack Aquitaine. Stephen responded by placing Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

, a key fortress loyal to Henry along the Thames Valley

The Thames Valley is an informally-defined sub-region of South East England, centred on the River Thames west of London, with Oxford as a major centre. Its boundaries vary with context. The area is a major tourist destination and economic hub, ...

, under siege, possibly in an attempt to force a successful end to the English conflict while Henry was still fighting for his territories in France. Henry moved quickly in response, avoiding open battle with Louis in Aquitaine and stabilising the Norman border, pillaging the Vexin and then striking south into Anjou against Geoffrey, capturing one of his main castles (Montsoreau

Montsoreau () is a commune of the Loire Valley in the Maine-et-Loire department in western France on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast and from Paris. The village is listed among '' The Most Beautiful Villages of France'' (french: Les Plus ...

). Louis fell ill and withdrew from the campaign, and Geoffrey was forced to come to terms with Henry.Gillingham (1984), p. 17.

Taking the English throne

Stockbridge, Hampshire

Stockbridge is a small town and civil parish in the Test Valley district of Hampshire, England. It is one of the smallest towns in the United Kingdom with a population of 592 at the 2011 census. It sits astride the River Test and at the foot of ...

, shortly before Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

in April. Details of their discussions are unclear, but it appears that the churchmen emphasised that while they supported Stephen as king, they sought a negotiated peace; Henry reaffirmed that he would avoid the English cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denomination ...

s and would not expect the bishops to attend his court.

To draw Stephen's forces away from Wallingford, Henry besieged Stephen's castle at Malmesbury

Malmesbury () is a town and civil parish in north Wiltshire, England, which lies approximately west of Swindon, northeast of Bristol, and north of Chippenham. The older part of the town is on a hilltop which is almost surrounded by the up ...

, and the King responded by marching west with an army to relieve it. Henry successfully evaded Stephen's larger army along the River Avon, preventing Stephen from forcing a decisive battle.Bradbury, p. 180. In the face of the increasingly wintry weather, the two men agreed to a temporary truce, leaving Henry to travel north through the Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

, where the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, announced his support for the cause. Henry was then free to turn his forces south against the besiegers at Wallingford. Despite only modest military successes, he and his allies now controlled the south-west, the Midlands and much of the north of England. Meanwhile, Henry was attempting to act the part of a legitimate king, witnessing marriages and settlements and holding court in a regal fashion.

Over the next summer, Stephen massed troops to renew the siege of Wallingford Castle in a final attempt to take the stronghold. The fall of Wallingford appeared imminent and Henry marched south to relieve the siege, arriving with a small army and placing Stephen's besieging forces under siege themselves.Bradbury, p. 183. Upon news of this, Stephen returned with a large army, and the two sides confronted each other across the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

at Wallingford in July. By this point in the war, the barons on both sides were eager to avoid an open battle,Bradbury, p. 183; King (2010), p. 277; Crouch (2002), p. 276. so members of the clergy brokered a truce, to the annoyance of both Henry and Stephen. Henry and Stephen took the opportunity to speak together privately about a potential end to the war; conveniently for Henry, Stephen's son Eustace fell ill and died shortly afterwards. This removed the most obvious other claimant to the throne, as while Stephen had another son, William, he was only a second son and appeared unenthusiastic about making a plausible claim on the throne. Fighting continued after Wallingford, but in a rather half-hearted fashion, while the English Church attempted to broker a permanent peace between the two sides.

In November the two leaders ratified the terms of a permanent peace. Stephen announced the Treaty of Winchester

The Treaty of Wallingford, also known as the Treaty of Winchester or the Treaty of Westminster, was an agreement reached in England in the summer of 1153. It effectively ended a civil war known as ''the Anarchy'' (1135–54), caused by a dispute o ...

in Winchester Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity,Historic England. "Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity (1095509)". ''National Heritage List for England''. Retrieved 8 September 2014. Saint Peter, Saint Paul and Saint Swithun, commonly known as Winches ...

: he recognised Henry as his adopted

Adoption is a process whereby a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents. Legal adoptions permanently transfer all rights and responsibilities, along with filiation, from ...

son and successor, in return for Henry paying homage to him; Stephen promised to listen to Henry's advice, but retained all his royal powers; Stephen's son William would pay homage to Henry and renounce his claim to the throne, in exchange for promises of the security of his lands; key royal castles would be held on Henry's behalf by guarantors whilst Stephen would have access to Henry's castles, and the numerous foreign mercenaries would be demobilised and sent home. Henry and Stephen sealed the treaty with a kiss of peace

The kiss of peace is an ancient traditional Christian greeting, sometimes also called the "holy kiss", "brother kiss" (among men), or "sister kiss" (among women). Such greetings signify a wish and blessing that peace be with the recipient, and bes ...

in the cathedral. The peace remained precarious, and Stephen's son William remained a possible future rival to Henry.Crouch (2002), p. 277. Rumours of a plot to kill Henry were circulating and, possibly as a consequence, Henry decided to return to Normandy for a period. Stephen fell ill with a stomach disorder

Stomach diseases include gastritis, gastroparesis, Crohn's disease and various cancers.

The stomach is an important organ in the body. It plays a vital role in digestion of foods, releases various enzymes and also protects the lower intestine fr ...

and died on 25 October 1154, allowing Henry to inherit the throne rather sooner than had been expected.

Reconstruction of royal government

On landing in England on 8 December 1154, Henry quickly took oaths of loyalty from some of the barons and was then crowned alongside Eleanor at

On landing in England on 8 December 1154, Henry quickly took oaths of loyalty from some of the barons and was then crowned alongside Eleanor at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

on 19 December.White (2000), p. 5. The royal court was gathered in April 1155, where the barons swore fealty to the King and his sons. Several potential rivals still existed, including Stephen's son William and Henry's brothers Geoffrey and William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, but they all died in the next few years, leaving Henry's position remarkably secure. Nonetheless, Henry inherited a difficult situation in England, as the kingdom had suffered extensively during the civil war. In many parts of the country the fighting had caused serious devastation, although some other areas remained largely unaffected.Barlow (1999), p. 181. Numerous "adulterine

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

", or unauthorised, castles had been built as bases for local lords. The royal forest law had collapsed in large parts of the country. The King's income had declined seriously and royal control over the coin mints remained limited.

Henry presented himself as the legitimate heir to Henry I and commenced rebuilding the kingdom in his image. Although Stephen had tried to continue Henry I's method of government during his reign, the younger Henry's new government characterised those nineteen years as a chaotic and troubled period, with all these problems resulting from Stephen's usurpation of the throne. Henry was also careful to show that, unlike his mother the Empress, he would listen to the advice and counsel of others. Various measures were immediately carried out although, since Henry spent six and a half years out of the first eight years of his reign in France, much work had to be done at a distance. The process of demolishing the unauthorised castles from the war continued.Amt, p. 44. Efforts were made to restore the system of royal justice and the royal finances. Henry also invested heavily in the construction and renovation of prestigious new royal buildings.

The King of Scotland and local Welsh rulers had taken advantage of the long civil war in England to seize disputed lands; Henry set about reversing this trend. In 1157 pressure from Henry resulted in the young King Malcolm of Scotland returning the lands in the north of England he had taken during the war; Henry promptly began to refortify the northern frontier. Restoring Anglo-Norman supremacy in Wales proved harder, and Henry had to fight two campaigns in north

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and south Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

in 1157 and 1158 before the Welsh princes Owain Gwynedd

Owain ap Gruffudd ( 23 or 28 November 1170) was King of Gwynedd, North Wales, from 1137 until his death in 1170, succeeding his father Gruffudd ap Cynan. He was called Owain the Great ( cy, Owain Fawr) and the first to be ...

and Rhys ap Gruffydd

Rhys ap Gruffydd, commonly known as The Lord Rhys, in Welsh ''Yr Arglwydd Rhys'' (c. 1132 – 28 April 1197) was the ruler of the Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth in south Wales from 1155 to 1197 and native Prince of Wales.

It was believed that he ...

submitted to his rule, agreeing to the pre-civil war borders.

Campaigns in Brittany, Toulouse and the Vexin

Thierry, Count of Flanders

Theoderic ( nl, Diederik, french: Thierry, german: Dietrich; – 17 January 1168), commonly known as Thierry of Alsace, was the fifteenth count of Flanders from 1128 to 1168. With a record of four campaigns in the Levant and Africa (including p ...

, who signed a military alliance with Henry, albeit with a clause that prevented the count from being forced to fight against Louis, his feudal lord.Dunbabin, p. 52. Further south, Theobald V, Count of Blois

Theobald V of Blois (1130 – 20 January 1191), also known as Theobald the Good (french: Thibaut le Bon), was Count of Blois from 1151 to 1191.

Biography

Theobald was son of Theobald II of Champagne and Matilda of Carinthia. Although he was the s ...

, an enemy of Louis, became another early ally of Henry. The resulting military tensions and the frequent face-to-face meetings to attempt to resolve them has led historian Jean Dunbabin to liken the situation to the period of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

in Europe in the 20th century.

On his return to the continent from England, Henry sought to secure his French lands and quash any potential rebellion. As a result, in 1154 Henry and Louis agreed to a peace treaty, under which Henry bought back the Vernon and the Neuf-Marché

Neuf-Marché is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in north-western France.

Geography

A forestry and farming village situated by the banks of the river Epte in the Pays de Bray, some east of Rouen at the junction ...

from Louis. The treaty appeared shaky, and tensions remained—in particular, Henry had not given homage to Louis for his French possessions. They met at Paris and Mont-Saint-Michel

Mont-Saint-Michel (; Norman: ''Mont Saint Miché''; ) is a tidal island and mainland commune in Normandy, France.

The island lies approximately off the country's north-western coast, at the mouth of the Couesnon River near Avranches and is ...

in 1158, agreeing to betroth Henry's eldest living son, the Young Henry, to Louis's daughter Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

.Dunbabin, p. 53. The marriage deal would have involved Louis granting the disputed territory of the Vexin

Vexin () is an historical county of northwestern France. It covers a verdant plateau on the right bank (north) of the Seine running roughly east to west between Pontoise and Romilly-sur-Andelle (about 20 km from Rouen), and north to south ...

to Margaret on her marriage to the Young Henry: while this would ultimately give Henry the lands that he claimed, it also cunningly implied that the Vexin was Louis's to give away in the first place, in itself a political concession. For a short while, a permanent peace between Henry and Louis looked plausible.

Meanwhile, Henry turned his attention to the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany ( br, Dugelezh Breizh, ; french: Duché de Bretagne) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of Europe, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, which neighboured his lands and was traditionally largely independent from the rest of France, with its own language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

and culture. The Breton dukes held little power across most of the duchy, which was mostly controlled by local lords. In 1148, Duke Conan III died and civil war broke out. Henry claimed to be the overlord of Brittany, on the basis that the duchy had owed loyalty to Henry I, and saw controlling the duchy both as a way of securing his other French territories and as a potential inheritance for one of his sons. Initially Henry's strategy was to rule indirectly through proxies, and accordingly, Henry supported Conan IV

Conan IV ( 1138 – February 20, 1171), called the Young, was the Duke of Brittany from 1156 to 1166. He was the son of Bertha, Duchess of Brittany, and her first husband, Alan, Earl of Richmond. Conan IV was his father's heir as Earl of Richmon ...

's claims over most of the duchy, partly because Conan had strong English ties and could be easily influenced. Conan's uncle, Hoël, continued to control the county of Nantes The counts of Nantes were originally the Frankish rulers of the Nantais under the Carolingians and eventually a capital city of the Duchy of Brittany. Their county served as a march against the Bretons of the Vannetais. Carolingian rulers would some ...

in the east until he was deposed in 1156 by Henry's brother, Geoffrey, possibly with Henry's support. When Geoffrey died in 1158, Conan attempted to reclaim Nantes but was opposed by Henry who annexed it for himself. Louis took no action to intervene as Henry steadily increased his power in Brittany.Hallam and Everard, p. 161.

Henry hoped to take a similar approach to regaining control of

Henry hoped to take a similar approach to regaining control of Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Par ...

in southern France. Toulouse, while technically part of the Duchy of Aquitaine, had become increasingly independent and was now ruled by Count Raymond V

Raymond is a male given name. It was borrowed into English from French (older French spellings were Reimund and Raimund, whereas the modern English and French spellings are identical). It originated as the Germanic ᚱᚨᚷᛁᚾᛗᚢᚾᛞ ( ...

, who had only a weak claim to the lands.Warren (2000), p. 85. Encouraged by Eleanor, Henry first allied himself with Raymond's enemy Raymond Berenguer of Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

and then in 1159 threatened to invade himself to depose the Count of Toulouse. Louis married his sister Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

*Konstanz, Germany, sometimes written as Constance in English

*Constance Bay, Ottawa, Canada

* Constance, Kentucky

* Constance, Minnesota

* Constance (Portugal)

* Mount Constance, Washington State

People

* Consta ...

to the Count in an attempt to secure his southern frontiers; nonetheless, when Henry and Louis discussed the matter of Toulouse, Henry left believing that he had the French King's support for military intervention. Henry invaded Toulouse, only to find Louis visiting Raymond in the city.Warren (2000), p. 87. Henry was not prepared to directly attack Louis, who was still his feudal lord, and withdrew, settling himself with ravaging the surrounding county, seizing castles and taking the province of Quercy

Quercy (; oc, Carcin , locally ) is a former province of France located in the country's southwest, bounded on the north by Limousin, on the west by Périgord and Agenais, on the south by Gascony and Languedoc, and on the east by Rouergue and Au ...

. The episode proved to be a long-running point of dispute between the two kings and the chronicler William of Newburgh called the ensuing conflict with Toulouse a "forty years' war".

In the aftermath of the Toulouse episode, Louis made an attempt to repair relations with Henry through an 1160 peace treaty: this promised Henry the lands and the rights of his grandfather, Henry I; it reaffirmed the betrothal of Young Henry and Margaret and the Vexin deal; and it involved Young Henry giving homage to Louis, a way of reinforcing the young boy's position as heir and Louis's position as king. Almost immediately after the peace conference, Louis shifted his position considerably. His wife Constance died and he married Adèle, the sister of the Counts of Blois and Champagne. Louis also betrothed daughters by Eleanor to Adèle's brothers Theobald V, Count of Blois

Theobald V of Blois (1130 – 20 January 1191), also known as Theobald the Good (french: Thibaut le Bon), was Count of Blois from 1151 to 1191.

Biography

Theobald was son of Theobald II of Champagne and Matilda of Carinthia. Although he was the s ...

, and Henry I, Count of Champagne

Henry I (December 1127 – March 16, 1181), known as the Liberal, was count of Champagne from 1152 to 1181. He was the eldest son of Count Theobald II of Champagne, who was also count of Blois, and his wife, Matilda of Carinthia.

Biography

Henry ...

.Warren (2000), p. 90. This represented an aggressive containment strategy towards Henry rather than the agreed rapprochement, and caused Theobald to abandon his alliance with Henry. Henry reacted angrily; the King had custody of both Young Henry and Margaret, and in November he bullied several papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

s into marrying them—despite the children being only five and three years old respectively—and promptly seized the Vexin. Now it was Louis's turn to be furious, as the move clearly broke the spirit of the 1160 treaty.

Military tensions between the two leaders immediately increased. Theobald mobilised his forces along the border with Touraine; Henry responded by attacking Chaumont Chaumont can refer to:

Places Belgium

* Chaumont-Gistoux, a municipality in the province of Walloon Brabant

France

* Chaumont-Porcien, in the Ardennes ''département''

* Chaumont, Cher, in the Cher ''département''

* Chaumont-le-Bois, in the C� ...

in Blois in a surprise attack; he successfully took Theobald's castle in a notable siege. At the start of 1161 war seemed likely to spread across the region, until a fresh peace was negotiated at Fréteval

Fréteval () is a commune in the French department of Loir-et-Cher. The village is located on the right bank of the river Loir. Archaeological evidence indicates that the site was occupied by the second century CE. In the Middle Ages, the fortifi ...

that autumn, followed by a second peace treaty in 1162, overseen by Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland ( it, Rolando), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a con ...

. Despite this temporary halt in hostilities, Henry's seizure of the Vexin proved to be a second long-running dispute between him and the kings of France.

Government, family and household

Empire and nature of government

Henry controlled more of France than any ruler since the

Henry controlled more of France than any ruler since the Carolingians