Henry David Thoreau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

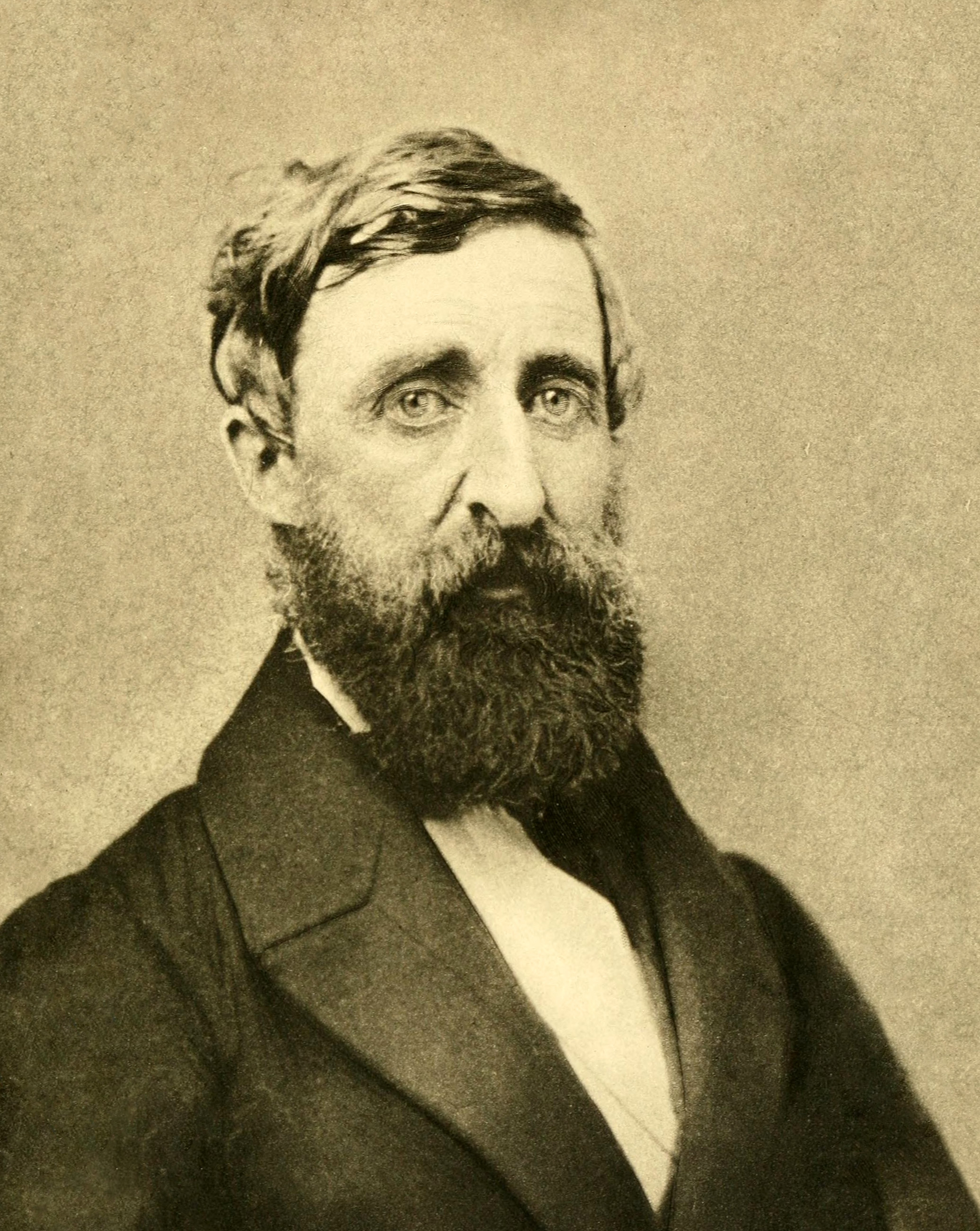

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist,

"Resistance to Civil Government"

. Retrieved October 2, 2020via Sniggle.

Henry David Thoreau was born David Henry Thoreau in

Henry David Thoreau was born David Henry Thoreau in

"Henry David Thoreau and 'Civil Disobedience'"

.

Chapter 2

. Princeton: Princeton University Press. so in 1835 he took a leave of absence from Harvard, during which he taught at a school in On April 18, 1841, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house.Cheever, Susan (2006). ''American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau; Their Lives, Their Loves, Their Work''. Detroit: Thorndike Press. p. 90. . There, from 1841 to 1844, he served as the children's tutor; he was also an editorial assistant, repairman and gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William Emerson on

On April 18, 1841, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house.Cheever, Susan (2006). ''American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau; Their Lives, Their Loves, Their Work''. Detroit: Thorndike Press. p. 90. . There, from 1841 to 1844, he served as the children's tutor; he was also an editorial assistant, repairman and gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William Emerson on

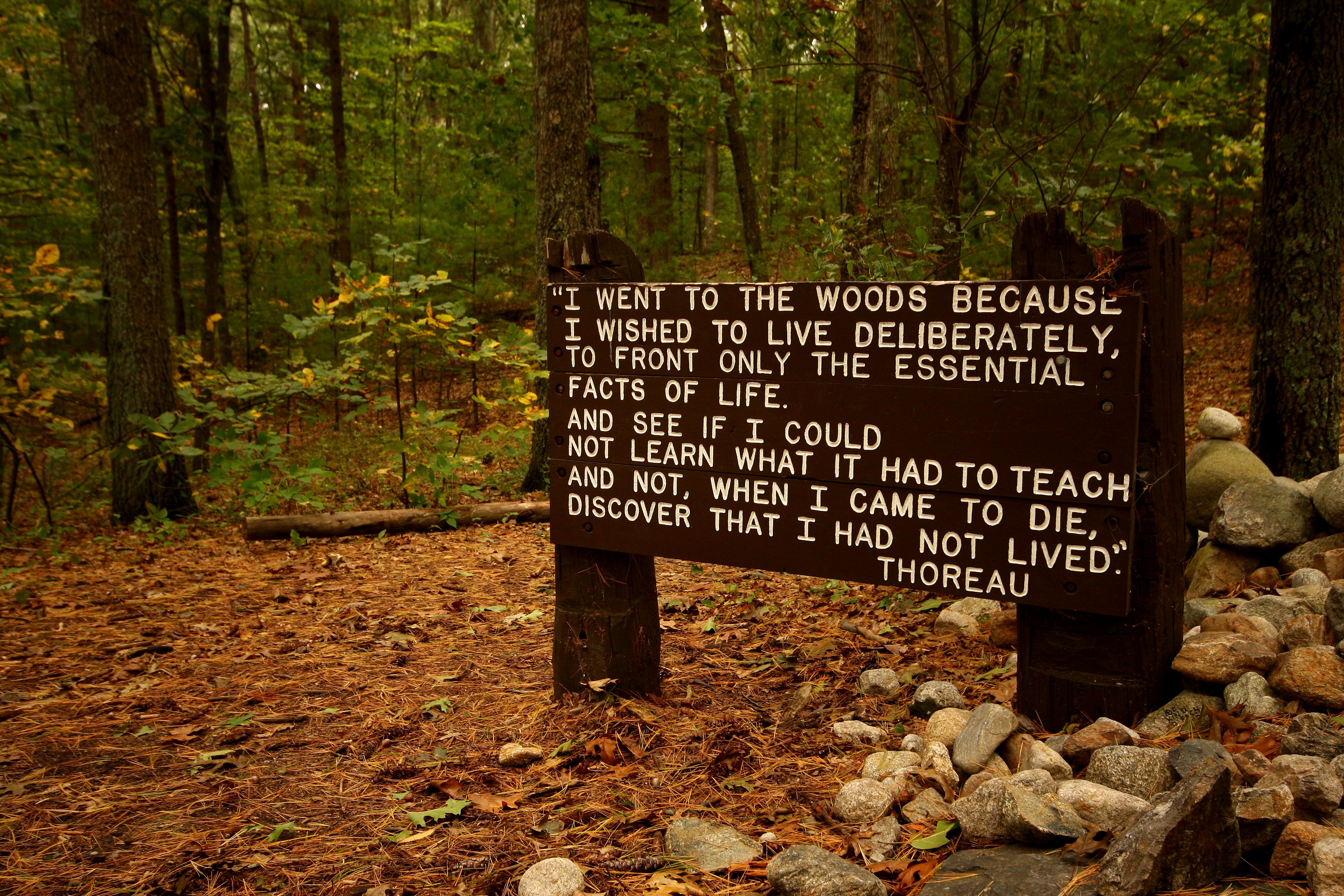

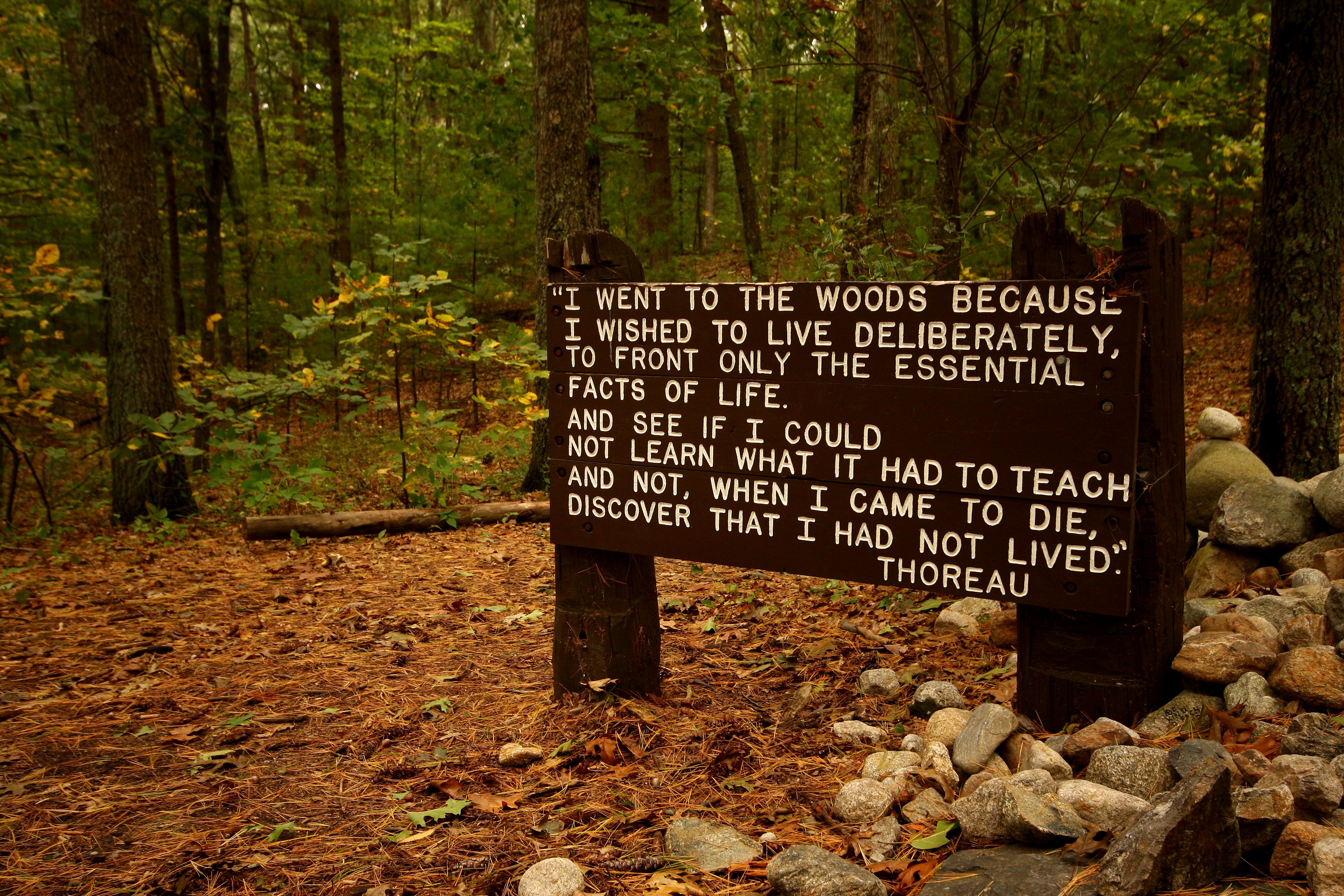

Thoreau felt a need to concentrate and work more on his writing. In 1845, Ellery Channing told Thoreau, "Go out upon that, build yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no other alternative, no other hope for you." Thus, on July 4, 1845, Thoreau embarked on a two-year experiment in

Thoreau felt a need to concentrate and work more on his writing. In 1845, Ellery Channing told Thoreau, "Go out upon that, build yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no other alternative, no other hope for you." Thus, on July 4, 1845, Thoreau embarked on a two-year experiment in  On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local

On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local

The Theory, Practice and Influence of Thoreau's Civil Disobedience

. William Cain, ed. (2006). ''A Historical Guide to Henry David Thoreau''. Cambridge: Oxford University Press. The experience had a strong impact on Thoreau. In January and February 1848, he delivered lectures on "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government", explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Bronson Alcott attended the lecture, writing in his journal on January 26: Thoreau revised the lecture into an essay titled " Resistance to Civil Government" (also known as "Civil Disobedience"). It was published by

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and narratives of travel and expedition. He read avidly on

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and narratives of travel and expedition. He read avidly on  He traveled to

He traveled to

Aware he was dying, Thoreau's last words were "Now comes good sailing", followed by two lone words, "moose" and "Indian". He died on May 6, 1862, at age 44.

Aware he was dying, Thoreau's last words were "Now comes good sailing", followed by two lone words, "moose" and "Indian". He died on May 6, 1862, at age 44.

Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead he sought a middle ground, the

Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead he sought a middle ground, the

Thoreau was fervently against

Thoreau was fervently against

from the Writings of Henry David Thoreau: The Digital Collection In addition, he lamented the newspaper editors who dismissed Brown and his scheme as "crazy". Thoreau was a proponent of

from the Writings of Henry David Thoreau: The Digital Collection writing: "Let not our Peace be proclaimed by the rust on our swords, or our inability to draw them from their scabbards; but let her at least have so much work on her hands as to keep those swords bright and sharp." Furthermore, in a formal lyceum debate in 1841, he debated the subject "Is it ever proper to offer forcible resistance?", arguing the affirmative. Likewise, his condemnation of the

Thoreau read contemporary works in the new science of biology, including the works of Alexander von Humboldt,

Thoreau read contemporary works in the new science of biology, including the works of Alexander von Humboldt,

Thoreau's political writings had little impact during his lifetime, as "his contemporaries did not see him as a theorist or as a radical", viewing him instead as a naturalist. They either dismissed or ignored his political essays, including ''Civil Disobedience''. The only two complete books (as opposed to essays) published in his lifetime, ''Walden'' and ''A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers'' (1849), both dealt with nature, in which he "loved to wander". His obituary was lumped in with others rather than as a separate article in an 1862 yearbook. Critics and the public continued either to disdain or to ignore Thoreau for years, but the publication of extracts from his journal in the 1880's by his friend H.G.O. Blake, and of a definitive set of Thoreau's works by the Riverside Insights, Riverside Press between 1893 and 1906, led to the rise of what literary historian Fred Lewis Pattee, F. L. Pattee called a "Thoreau cult."Pattee, Fred Lewis, ''A History of American Literature Since 1870'', Ch.VII, pp.138-139 (Appleton: New York, London, 1915).

Thoreau's political writings had little impact during his lifetime, as "his contemporaries did not see him as a theorist or as a radical", viewing him instead as a naturalist. They either dismissed or ignored his political essays, including ''Civil Disobedience''. The only two complete books (as opposed to essays) published in his lifetime, ''Walden'' and ''A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers'' (1849), both dealt with nature, in which he "loved to wander". His obituary was lumped in with others rather than as a separate article in an 1862 yearbook. Critics and the public continued either to disdain or to ignore Thoreau for years, but the publication of extracts from his journal in the 1880's by his friend H.G.O. Blake, and of a definitive set of Thoreau's works by the Riverside Insights, Riverside Press between 1893 and 1906, led to the rise of what literary historian Fred Lewis Pattee, F. L. Pattee called a "Thoreau cult."Pattee, Fred Lewis, ''A History of American Literature Since 1870'', Ch.VII, pp.138-139 (Appleton: New York, London, 1915).

/ref> Thoreau's writings went on to influence many public figures. Political leaders and reformers like Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Mohandas Gandhi, U.S. President John F. Kennedy, American civil rights activist

Confessions of a Right-Wing Liberal

, ''Ramparts (magazine), Ramparts'', VI, 4, June 15, 1968 Thoreau also influenced many artists and authors including Edward Abbey, Willa Cather, Marcel Proust, William Butler Yeats, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, E. B. White, Lewis Mumford, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alexander Posey, and Gustav Stickley. Thoreau also influenced naturalists like John Burroughs, John Muir, E. O. Wilson, Edwin Way Teale, Joseph Wood Krutch, B. F. Skinner, David Brower, and Loren Eiseley, whom ''Publishers Weekly'' called "the modern Thoreau". Thoreau's friend William Ellery Channing (poet), William Ellery Channing published his first biography, ''Thoreau the Poet-Naturalist'', in 1873. English writer Henry Stephens Salt wrote a biography of Thoreau in 1890, which popularized Thoreau's ideas in Britain: George Bernard Shaw, Edward Carpenter, and Robert Blatchford were among those who became Thoreau enthusiasts as a result of Salt's advocacy. Mohandas Gandhi first read ''Walden'' in 1906 while working as a civil rights activist in Johannesburg, South Africa. He first read ''Civil Disobedience'' "while he sat in a South African prison for the crime of nonviolently protesting discrimination against the Indian population in the Transvaal Colony, Transvaal. The essay galvanized Gandhi, who wrote and published a synopsis of Thoreau's argument, calling its 'incisive logic ... unanswerable' and referring to Thoreau as 'one of the greatest and most moral men America has produced'." He told American reporter Webb Miller (journalist), Webb Miller, "[Thoreau's] ideas influenced me greatly. I adopted some of them and recommended the study of Thoreau to all of my friends who were helping me in the cause of Indian Independence. Why I actually took the name of my movement from Thoreau's essay 'On the Duty of Civil Disobedience', written about 80 years ago."

"Anarchisme et naturisme, aujourd'hui." by Cathy Ytak

in Spain, France,

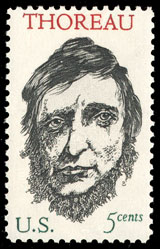

and Portugal.Freire, Jo├Żo. "Anarchisme et naturisme au Portugal, dans les ann├®es 1920" in ''Les anarchistes du Portugal''. [Bibliographic data necessary for this ref.] For the 200th anniversary of his birth, publishers released several new editions of his work: a recreation of ''Walden'' 1902 edition with illustrations, a picture book with excerpts from ''Walden'', and an annotated collection of Thoreau's essays on slavery. The United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Thoreau on May 23, 2017, in Concord, MA.

/ref> which Lowell republished as a chapter in his ''My Study Windows'',Lowell, James Russell, ''My Study Windows'', Ch.VII, pp.193-209 (Osgood: Boston 1871).

/ref> derided Thoreau as a humorless poseur trafficking in commonplaces, a sentimentalist lacking in imagination, a "Diogenes in his barrel," resentfully criticizing what he could not attain. Lowell's caustic analysis influenced Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, who criticized Thoreau as a "skulker," saying "He did not wish virtue to go out of him among his fellow-men, but slunk into a corner to hoard it for himself."

from the Writings of Henry David Thoreau: The Digital Collection * ''Remarks After the Hanging of John Brown'' (1859) * ''

selections by Richard F. Fleck

* ''Wild Fruits'' (Unfinished at his death, W.W. Norton, 1999)

''The Disarming Honesty of Henry David Thoreau''

* Conrad, Randall

* Cramer, Jeffrey S. ''Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson'' (Counterpoint Press, 2019). * Dean, Bradley P. ed., ''Letters to a Spiritual Seeker''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004. * Finley, James S., ed. ''Henry David Thoreau in Context'' (Cambridge UP, 2017). * Furtak, Rick, Ellsworth, Jonathan, and Reid, James D., eds. ''Thoreau's Importance for Philosophy''. New York: Fordham University Press, 2012. * Gionfriddo, Michael. "Thoreau, the Work of Breathing, and Building Castles in the Air: Reading Walden's 'Conclusion'." ''The Concord Saunterer'' 25 (2017): 49-90

online

. * Guhr, Sebastian. ''Mr. Lincoln & Mr. Thoreau''. S. Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2021. * Harding, Walter. ''The Days of Henry Thoreau''. Princeton University Press, 1982. * Hendrick, George. "The Influence of Thoreau's 'Civil Disobedience' on Gandhi's Satyagraha." ''The New England Quarterly'' 29, no. 4 (December 1956). 462ŌĆō471. * * Howarth, William. ''The Book of Concord: Thoreau's Life as a Writer''. Viking Press, 1982 * Judd, Richard W. ''Finding Thoreau: The Meaning of Nature in the Making of an Environmental Icon'' (2018

excerpt

* McGregor, Robert Kuhn. ''A Wider View of the Universe: Henry Thoreau's Study of Nature'' (U of Illinois Press, 1997). * Annie Russell Marble, Marble, Annie Russell. ''Thoreau: His Home, Friends and Books''. New York: AMS Press. 1969 [1902] * Myerson, Joel et al. ''The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau''. Cambridge University Press. 1995 * Nash, Roderick. ''Henry David Thoreau, Philosopher'' * Paolucci, Stefano

"The Foundations of Thoreau's 'Castles in the Air'"

, ''Thoreau Society Bulletin'', No. 290 (Summer 2015), 10. (See also th

Full Unedited Version

of the same article.) * Parrington, Vernon.

''. V 2 online. 1927 * Parrington, Vernon L

* Petroski, Henry. "H. D. Thoreau, Engineer." ''American Heritage of Invention and Technology'', Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 8ŌĆō16 * Petrulionis, Sandra Harbert, ed., ''Thoreau in His Own Time: A Biographical Chronicle of His Life, Drawn From Recollections, Interviews, and Memoirs by Family, Friends, and Associates.'' Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2012. * Richardson, Robert D. ''Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind''. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles. 1986. * * * Ridl, Jack.

" Scintilla (poem on Thoreau's last words) * Schneider, Richard ''Civilizing Thoreau: Human Ecology and the Emerging Social Sciences in the Major Works'' Rochester, New York. Camden House. 2016. * Smith, David C. "The Transcendental Saunterer: Thoreau and the Search for Self." Savannah, Georgia: Frederic C. Beil, 1997. * Sullivan, Mark W. "Henry David Thoreau in the American Art of the 1950s." ''The Concord Saunterer: A Journal of Thoreau Studies'', New Series, Vol. 18 (2010), pp. 68ŌĆō89. * Sullivan, Mark W. ''Picturing Thoreau: Henry David Thoreau in American Visual Culture.'' Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2015 * Alfred I. Tauber, Tauber, Alfred I. ''Henry David Thoreau and the Moral Agency of Knowing''. University of California, Berkeley. 2001.

Henry David Thoreau

ŌĆō ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''

Henry David Thoreau

ŌĆō ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' * Thorson, Robert M. ''The Boatman: Henry David Thoreau's River Years'' (Harvard UP, 2017), on his scientific study of the Concord River in the late 1850s. * Thorson, Robert M. ''Walden's Shore: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Science'' (2015). * Thorson, Robert M. ''The Guide to Walden Pond: An Exploration of the History, Nature, Landscape, and Literature of One of America's Most Iconic Places'' (2018). * * Laura Walls, Walls, Laura Dassow. ''Seeing New Worlds: Henry David Thoreau and 19th Century Science''. University of Wisconsin. 1995. * Laura Walls, Walls, Laura Dassow. ''Henry David Thoreau: A Life''. The University of Chicago Press. 2017. * John William Ward (professor), Ward, John William. 1969 ''Red, White, and Blue: Men, Books, and Ideas in American Culture''. New York: Oxford University Press

The Thoreau Society

The Thoreau Edition

"Writings of Emerson and Thoreau"

from C-SPAN's ''American Writers: A Journey Through History''

Works by Thoreau

at Open Library

Poems by Thoreau

at the Academy of American Poets

The Thoreau Reader

by ''Thoreau Society, The Thoreau Society''

The Writings of Henry David Thoreau

at ''The Walden Woods Project''

at the Concord Free Public Library

Henry David Thoreau Online

Ćō The Works and Life of Henry D. Thoreau {{DEFAULTSORT:Thoreau, Henry David Henry David Thoreau, 1817 births 1862 deaths 19th-century American philosophers 19th-century American poets 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis 19th-century diarists American abolitionists American anarchists American diarists American environmentalists American essayists American male essayists American male non-fiction writers American male poets American naturalists American nature writers American naturists American nomads American non-fiction environmental writers American opinion journalists American people of French descent American political philosophers American social commentators American spiritual writers American surveyors American tax resisters American travel writers Anarchism Anarchist writers Anti-consumerists Civil disobedience Critics of work and the work ethic American cultural critics Ecological succession Environmental writers Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Harvard College alumni Hasty Pudding alumni Hikers Tuberculosis deaths in Massachusetts Lecturers Left-libertarians Pantheists People from Concord, Massachusetts Philosophers from Massachusetts Philosophers of culture Philosophers of history Philosophers of love Philosophers of mind Philosophers of science Poets from Massachusetts Simple living advocates Social critics Social philosophers Underground Railroad people

essay

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal a ...

ist, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

, and philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, Žå╬╣╬╗ŽīŽā╬┐Žå╬┐Žé, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden

''Walden'' (; first published in 1854 as ''Walden; or, Life in the Woods'') is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon the author's simple living in natural surroundings. The work is part ...

'', a reflection upon simple living

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

in natural surroundings, and his essay "Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

" (originally published as "Resistance to Civil Government"), an argument for disobedience to an unjust state.

Thoreau's books, articles, essays, journals, and poetry amount to more than 20 volumes. Among his lasting contributions are his writings on natural history and philosophy, in which he anticipated the methods and findings of ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overlaps wi ...

and environmental history

Environmental history is the study of human interaction with the natural world over time, emphasising the active role nature plays in influencing human affairs and vice versa.

Environmental history first emerged in the United States out of th ...

, two sources of modern-day environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment, particularly as the measure for this health seek ...

. His literary

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

style interweaves close observation of nature, personal experience, pointed rhetoric, symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

ic meanings, and historical lore, while displaying a poetic sensibility, philosophical austerity

Austerity is a set of political-economic policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits through spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both. There are three primary types of austerity measures: higher taxes to fund spend ...

, and attention to practical detail.Thoreau, Henry David. ''A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers'' / ''Walden'' / ''The Maine Woods'' / ''Cape Cod''. Library of America. . He was also deeply interested in the idea of survival in the face of hostile elements, historical change, and natural decay; at the same time he advocated abandoning waste and illusion

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

Illusions may o ...

in order to discover life's true essential needs.

Thoreau was a lifelong abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, delivering lectures that attacked the fugitive slave law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 ŌĆō February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one whi ...

and defending the abolitionist John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800ŌĆō1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763ŌĆō1842), Ir ...

. Thoreau's philosophy of civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

later influenced the political thoughts and actions of such notable figures as Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, ąøąĄą▓ ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░ąĄą▓ąĖčć ąóąŠą╗čüč鹊ą╣,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 ŌĆō 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 ŌĆō April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

Thoreau is sometimes referred to as an anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

. In "Civil Disobedience", Thoreau wrote: "I heartily accept the 'That government is best which governs least;' and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I 'That government is best which governs not at all;' and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. ... But, to speak practically and as a cit┬Łi┬Łzen, unlike those who call themselves no-gov┬Łernment men, I ask for, not at once no gov┬Łernment, but ''at once'' a better government."Thoreau, Henry David (1849)"Resistance to Civil Government"

. Retrieved October 2, 2020via Sniggle.

Pronunciation of his name

Amos Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 ŌĆō March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and a ...

and Thoreau's aunt each wrote that "Thoreau" is pronounced like the word ''thorough'' ( ŌĆöin General American

General American English or General American (abbreviated GA or GenAm) is the umbrella accent of American English spoken by a majority of Americans. In the United States it is often perceived as lacking any distinctly regional, ethnic, or so ...

, but more precisely ŌĆöin 19th-century New England). Edward Waldo Emerson

Edward Waldo Emerson (July 10, 1844 ŌĆō January 27, 1930) was an American physician, writer and lecturer.

Biography

Emerson was born in Concord, Massachusetts. He was a son of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Lidian Jackson Emerson, and educated at Harv ...

wrote that the name should be pronounced "Th├│-row", with the ''h'' sounded and stress on the first syllable. Among modern-day American English speakers, it is perhaps more commonly pronounced ŌĆöwith stress on the second syllable.

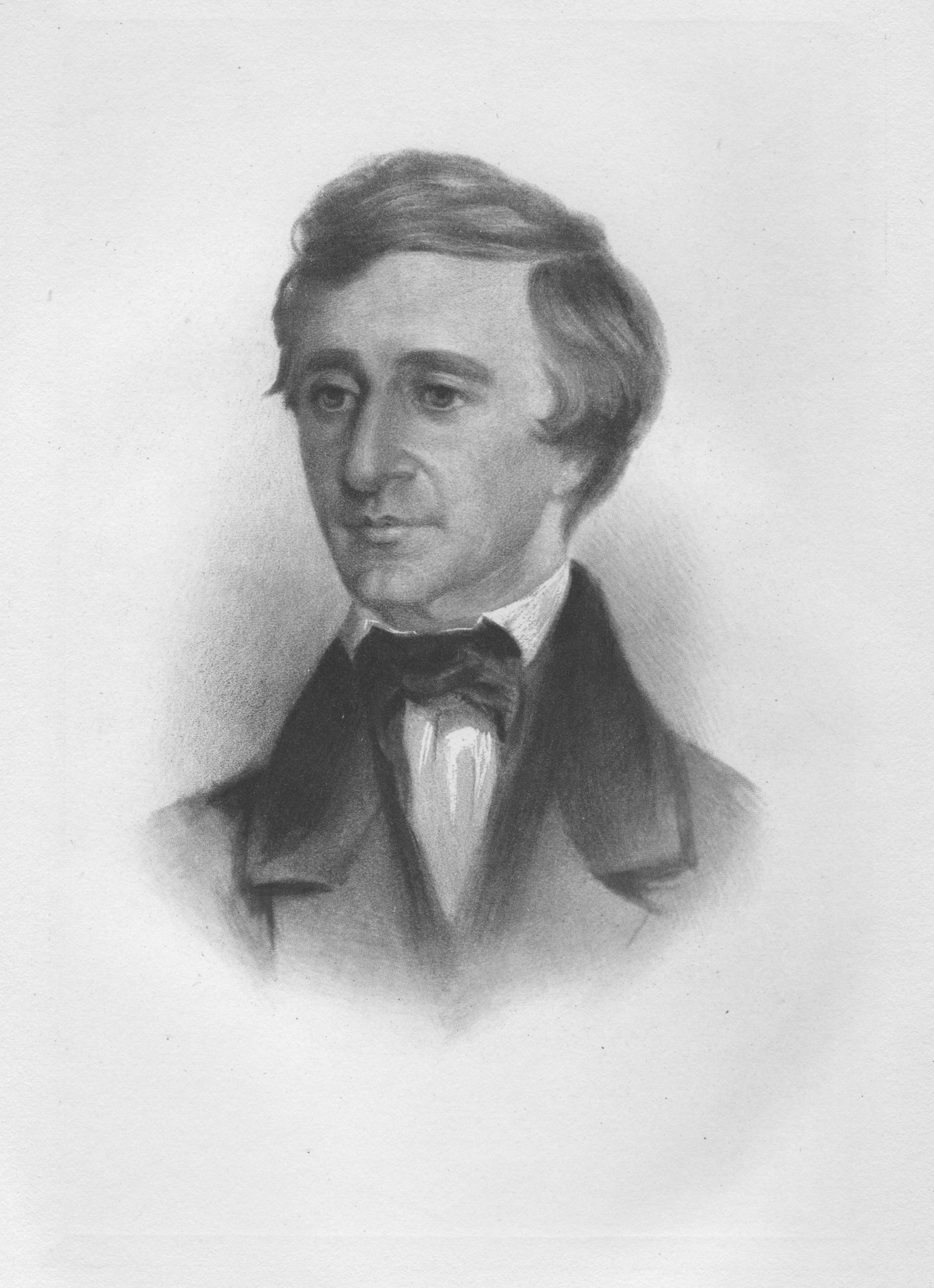

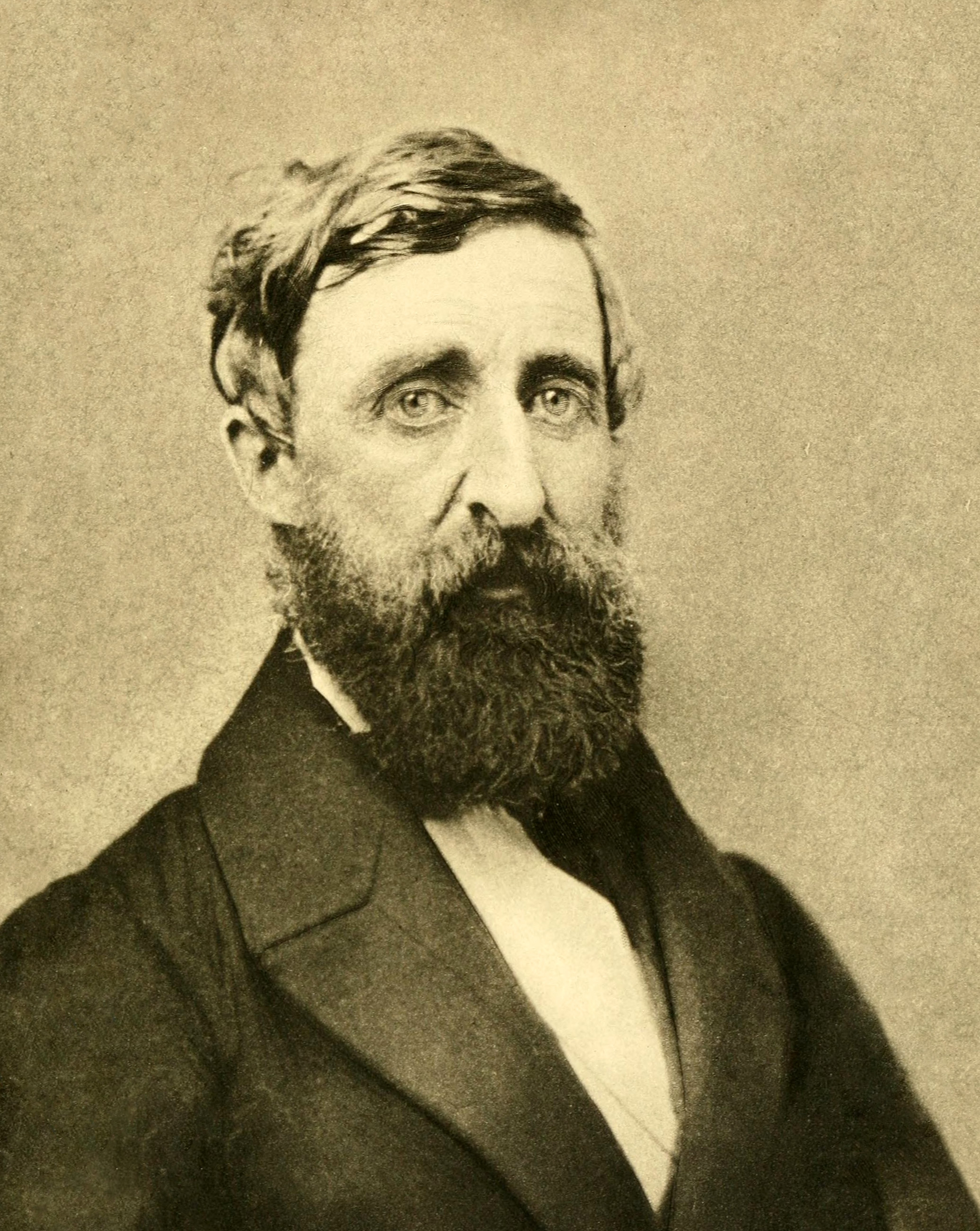

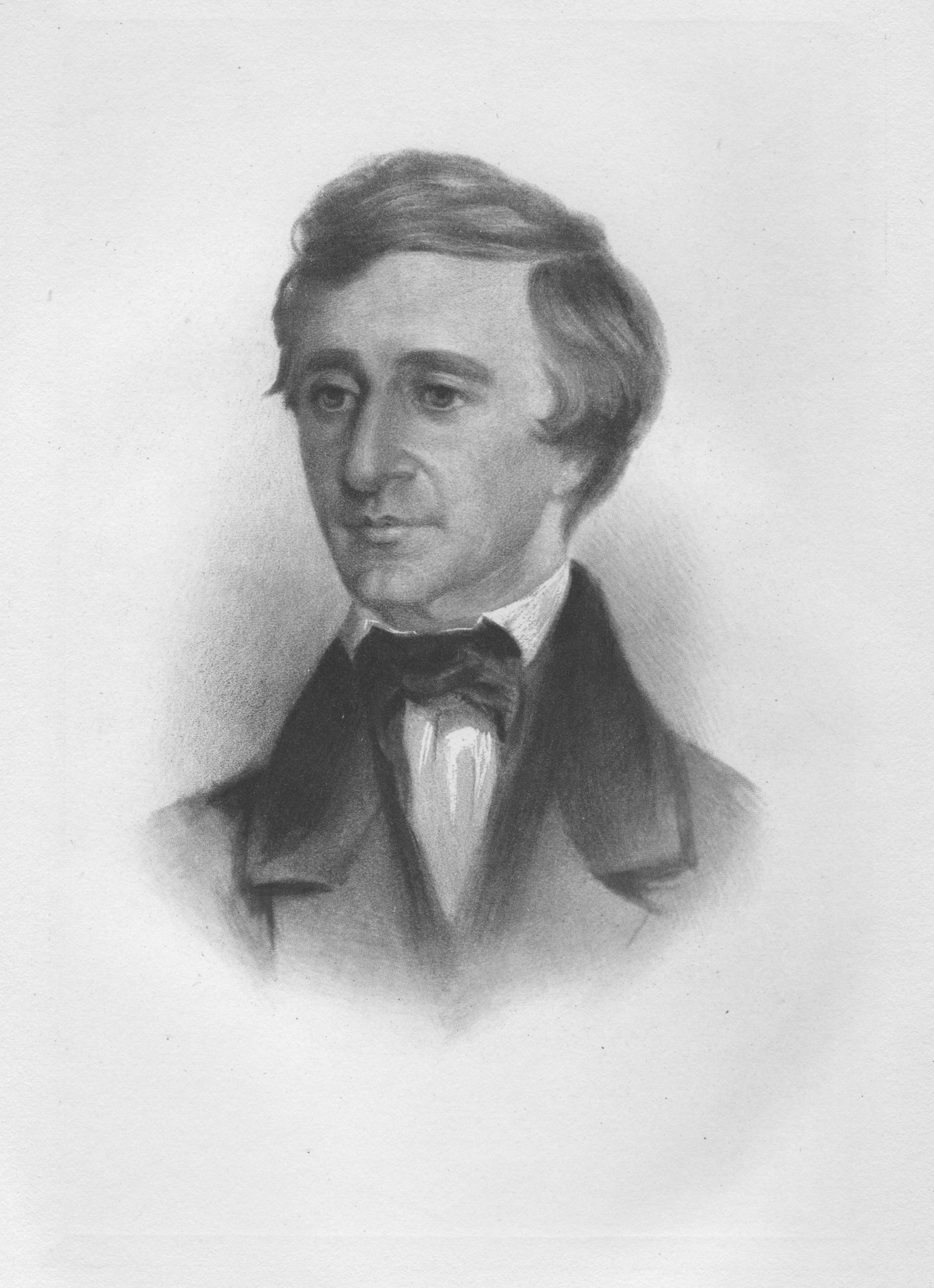

Physical appearance

Thoreau had a distinctive appearance, with a nose that he called his "most prominent feature". Of his appearance and disposition, Ellery Channing wrote:His face, once seen, could not be forgotten. The features were quite marked: the nose aquiline or very Roman, like one of the portraits ofCaesar Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC ŌĆō 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...(more like a beak, as was said); large overhanging brows above the deepest set blue eyes that could be seen, in certain lights, and in others gray,ŌĆöeyes expressive of all shades of feeling, but never weak or near-sighted; the forehead not unusually broad or high, full of concentrated energy and purpose; the mouth with prominent lips, pursed up with meaning and thought when silent, and giving out when open with the most varied and unusual instructive sayings.

Life

Early life and education, 1817ŌĆō1837

Henry David Thoreau was born David Henry Thoreau in

Henry David Thoreau was born David Henry Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts

Concord () is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the United States. At the 2020 census, the town population was 18,491. The United States Census Bureau considers Concord part of Greater Boston. The town center is near where the conflu ...

, into the "modest New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

family" McElroy, Wendy (July 30, 2005"Henry David Thoreau and 'Civil Disobedience'"

.

LewRockwell.com

Llewellyn Harrison Rockwell Jr. (born July 1, 1944) is an American author, editor, and political consultant. A libertarian and a self-professed anarcho-capitalist, he founded and is the chairman of the Mises Institute, a non-profit dedicated to ...

. of John Thoreau, a pencil maker, and Cynthia Dunbar. His father was of French Protestant descent. His paternal grandfather had been born on the UK crown dependency island of Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, J├©rri, label=J├©rriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; J├©rriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependencies, Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west F ...

. His maternal grandfather, Asa Dunbar, led Harvard's 1766 student "Butter Rebellion The Butter Rebellion, which took place at Harvard University in 1766, was the first recorded Harvard student protest in what is now the United States. In the decade preceding the American Revolution, economic difficulties made the acquisition of fre ...

", the first recorded student protest in the American colonies. David Henry was named after his recently deceased paternal uncle, David Thoreau. He began to call himself Henry David after he finished college; he never petitioned to make a legal name change.

He had two older siblings, Helen and John Jr., and a younger sister, Sophia Thoreau

Sophia Elizabeth Thoreau (1819ŌĆō1876) was an American editor. As the sister of Henry David Thoreau and his close collaborator, she was responsible for the posthumous publication of many of his well-known works.

Sophia Thoreau was born in Chel ...

. None of the children married. Helen (1812ŌĆō1849) died at age 37 years, from tuberculosis. John Jr. (1814ŌĆō1842) died at age 27, of tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

after cutting himself while shaving. Henry David (1817ŌĆō1862) died at age 44, of tuberculosis. Sophia (1819ŌĆō1876) survived him by 14 years, dying at age 56 years, of tuberculosis.

He studied at Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

between 1833 and 1837. He lived in Hollis Hall

This is a list of dormitories at Harvard College. Only freshmen live in these dormitories, which are located in and around Harvard Yard. Sophomores, juniors and seniors live in the House system.

Apley Court

South of Harvard Yard on Holyoke Stre ...

and took courses in rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

, classics, philosophy, mathematics, and science. He was a member of the Institute of 1770 (now the Hasty Pudding Club

The Hasty Pudding Club, often referred to simply as the Pudding, is a social club at Harvard University, and one of three sub-organizations that comprise the Hasty Pudding - Institute of 1770. The club's motto, ''Concordia Discors'' (discordant h ...

). According to legend, Thoreau refused to pay the five-dollar fee (approximately ) for a Harvard diploma. In fact, the master's degree he declined to purchase had no academic merit: Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

offered it to graduates "who proved their physical worth by being alive three years after graduating, and their saving, earning, or inheriting quality or condition by having Five Dollars to give the college". He commented, "Let every sheep keep its own skin", a reference to the tradition of using sheepskin

Sheepskin is the Hide (skin), hide of a Domestic sheep, sheep, sometimes also called lambskin. Unlike common leather, sheepskin is Tanning (leather), tanned with the Wool, fleece intact, as in a Fur, pelt.Delbridge, Arthur, "The Macquarie Dictiona ...

vellum

Vellum is prepared animal skin or membrane, typically used as writing material. Parchment is another term for this material, from which vellum is sometimes distinguished, when it is made from calfskin, as opposed to that made from other anima ...

for diplomas.

Thoreau's birthplace still exists on Virginia Road in Concord. The house has been restored by the Thoreau Farm Trust, a nonprofit organization, and is now open to the public.

Return to Concord, 1837ŌĆō1844

The traditional professions open to college graduatesŌĆölaw, the church, business, medicineŌĆödid not interest Thoreau,Sattelmeyer, Robert (1988). ''Thoreau's Reading: A Study in Intellectual History with Bibliographical Catalogue''Chapter 2

. Princeton: Princeton University Press. so in 1835 he took a leave of absence from Harvard, during which he taught at a school in

Canton, Massachusetts

Canton is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 24,370 at the 2020 census. Canton is part of Greater Boston, about 15 miles (24 kilometers) southwest of downtown Boston.

Hist ...

, living for two years at an earlier version of today's Colonial Inn in Concord. His grandfather owned the earliest of the three buildings that were later combined.''The History of Concord, Massachusetts, Vol. I, Colonial Concord, Volume 1'', Alfred Sereno Hudson (1904), p. 311 After he graduated in 1837, Thoreau joined the faculty of the Concord public school, but he resigned after a few weeks rather than administer corporal punishment. He and his brother John then opened the Concord Academy, a grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

in Concord, in 1838. They introduced several progressive concepts, including nature walks and visits to local shops and businesses. The school closed when John became fatally ill from tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

in 1842 after cutting himself while shaving. He died in Henry's arms.

Upon graduation Thoreau returned home to Concord, where he met Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

through a mutual friend. Emerson, who was 14 years his senior, took a paternal and at times patron-like interest in Thoreau, advising the young man and introducing him to a circle of local writers and thinkers, including Ellery Channing, Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 ŌĆō July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

, Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 ŌĆō March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and a ...

, and Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 ŌĆō May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

and his son Julian Hawthorne

Julian Hawthorne (June 22, 1846 – July 14, 1934) was an American writer and journalist, the son of novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody. He wrote numerous poems, novels, short stories, mysteries and detective fiction, essays, t ...

, who was a boy at the time.

Emerson urged Thoreau to contribute essays and poems to a quarterly periodical, ''The Dial

''The Dial'' was an American magazine published intermittently from 1840 to 1929. In its first form, from 1840 to 1844, it served as the chief publication of the Transcendentalists. From the 1880s to 1919 it was revived as a political review and ...

'', and lobbied the editor, Margaret Fuller, to publish those writings. Thoreau's first essay published in ''The Dial'' was "Aulus Persius Flaccus", an essay on the Roman poet and satirist, in July 1840. It consisted of revised passages from his journal, which he had begun keeping at Emerson's suggestion. The first journal entry, on October 22, 1837, reads, "'What are you doing now?' he asked. 'Do you keep a journal?' So I make my first entry to-day."

Thoreau was a philosopher of nature and its relation to the human condition. In his early years he followed transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

, a loose and eclectic idealist

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to id ...

philosophy advocated by Emerson, Fuller, and Alcott. They held that an ideal spiritual state transcends, or goes beyond, the physical and empirical, and that one achieves that insight via personal intuition rather than religious doctrine. In their view, Nature is the outward sign of inward spirit, expressing the "radical correspondence of visible things and human thoughts", as Emerson wrote in ''Nature'' (1836).

On April 18, 1841, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house.Cheever, Susan (2006). ''American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau; Their Lives, Their Loves, Their Work''. Detroit: Thorndike Press. p. 90. . There, from 1841 to 1844, he served as the children's tutor; he was also an editorial assistant, repairman and gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William Emerson on

On April 18, 1841, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house.Cheever, Susan (2006). ''American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau; Their Lives, Their Loves, Their Work''. Detroit: Thorndike Press. p. 90. . There, from 1841 to 1844, he served as the children's tutor; he was also an editorial assistant, repairman and gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William Emerson on Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull an ...

, and tutored the family's sons while seeking contacts among literary men and journalists in the city who might help publish his writings, including his future literary representative Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 ŌĆō November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

.

Thoreau returned to Concord and worked in his family's pencil

A pencil () is a writing or drawing implement with a solid pigment core in a protective casing that reduces the risk of core breakage, and keeps it from marking the user's hand.

Pencils create marks by physical abrasion, leaving a trail ...

factory, which he would continue to do alongside his writing and other work for most of his adult life. He rediscovered the process of making good pencils with inferior graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on large ...

by using clay as the binder. This invention allowed profitable use of a graphite source found in New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

that had been purchased in 1821 by Thoreau's uncle, Charles Dunbar. The process of mixing graphite and clay, known as the Cont├® process, had been first patented by Nicolas-Jacques Cont├®

Nicolas-Jacques Cont├® (4 August 1755 ŌĆō 6 December 1805) was a French painter, balloonist, army officer, and inventor of the modern pencil.

He was born at Saint-C├®neri-pr├©s-S├®es (now Aunou-sur-Orne) in Normandy and distinguished himself for ...

in 1795. The company's other source of graphite had been Tantiusques

Tantiusques ("Tant-E-oos-kwiss") is a open space reservation and historic site registered with the National Register of Historic Places. The reservation is located in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, and is owned and managed by The Trustees of Rese ...

, a mine operated by Native Americans in Sturbridge, Massachusetts

Sturbridge is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. It is home to Old Sturbridge Village living history museum and other sites of historical interest such as Tantiusques.

The population was 9,867 at the 2020 census, with mo ...

. Later, Thoreau converted the pencil factory to produce plumbago, a name for graphite at the time, which was used in the electrotyping

Electrotyping (also galvanoplasty) is a chemical method for forming metal parts that exactly reproduce a model. The method was invented by Moritz von Jacobi

Moritz Hermann or Boris Semyonovich (von) Jacobi (russian: ąæąŠčĆąĖčü ąĪąĄą╝čæąĮąŠą▓ąĖ ...

process.

Once back in Concord, Thoreau went through a restless period. In April 1844 he and his friend Edward Hoar accidentally set a fire that consumed of Walden Woods.

"Civil Disobedience" and the Walden years, 1845ŌĆō1850

simple living

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

, moving to a small house he had built on land owned by Emerson in a second growth forest

A secondary forest (or second-growth forest) is a forest or woodland area which has re-grown after a timber harvest or clearing for agriculture, until a long enough period has passed so that the effects of the disturbance are no longer evident. I ...

around the shores of Walden Pond

Walden Pond is a pond in Concord, Massachusetts, in the United States. A famous example of a kettle hole, it was formed by retreating glaciers 10,000ŌĆō12,000 years ago. The pond is protected as part of Walden Pond State Reservation, a state pa ...

. The house was in "a pretty pasture and woodlot" of that Emerson had bought, from his family home. Whilst there, he wrote his only extended piece of literary criticism, "Thomas Carlyle and His Works

"Thomas Carlyle and His Works" is an essay written by Henry David Thoreau that praises the writings of Thomas Carlyle.

The essay demonstrates a few themes that show up elsewhere in Thoreau's writings. First of these is Thoreau's eagerness to fi ...

".

On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local

On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local tax collector

A tax collector (also called a taxman) is a person who collects unpaid taxes from other people or corporations. The term could also be applied to those who audit tax returns. Tax collectors are often portrayed as being evil, and in the modern wo ...

, Sam Staples, who asked him to pay six years of delinquent poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

. Thoreau refused because of his opposition to the MexicanŌĆōAmerican War

The MexicanŌĆōAmerican War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

and slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slaveŌĆösomeone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and he spent a night in jail because of this refusal. The next day Thoreau was freed when someone, likely to have been his aunt, paid the tax, against his wishes.Rosenwald, Lawrence.The Theory, Practice and Influence of Thoreau's Civil Disobedience

. William Cain, ed. (2006). ''A Historical Guide to Henry David Thoreau''. Cambridge: Oxford University Press. The experience had a strong impact on Thoreau. In January and February 1848, he delivered lectures on "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government", explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Bronson Alcott attended the lecture, writing in his journal on January 26: Thoreau revised the lecture into an essay titled " Resistance to Civil Government" (also known as "Civil Disobedience"). It was published by

Elizabeth Peabody

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody (May 16, 1804January 3, 1894) was an American educator who opened the first English-language kindergarten in the United States. Long before most educators, Peabody embraced the premise that children's play has intrinsic de ...

in the ''Aesthetic Papers'' in May 1849. Thoreau had taken up a version of Percy Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achie ...

's principle in the political poem "The Mask of Anarchy

''The Masque of Anarchy'' (or ''The Mask of Anarchy'') is a British political poem written in 1819 (see 1819 in poetry) by Percy Bysshe Shelley following the Peterloo Massacre of that year. In his call for freedom, it is perhaps the first moder ...

" (1819), which begins with the powerful images of the unjust forms of authority of his time and then imagines the stirrings of a radically new form of social action.

At Walden Pond, Thoreau completed a first draft of ''A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers

''A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers'' (1849) is a book by American writer Henry David Thoreau (1817ŌĆō1862). It recounts his experience on a boat trip with his brother on the Concord River and Merrimack River.

Overview

''A Week on the ...

'', an elegy

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

to his brother John, describing their trip to the White Mountains in 1839. Thoreau did not find a publisher for the book and instead printed 1,000 copies at his own expense; fewer than 300 were sold. He self-published the book on the advice of Emerson, using Emerson's publisher, Munroe, who did little to publicize the book.

In August 1846, Thoreau briefly left Walden to make a trip to Mount Katahdin

Mount Katahdin ( ) is the highest mountain in the U.S. state of Maine at . Named Katahdin, which means "Great Mountain", by the Penobscot Native Americans, it is within Northeast Piscataquis, Piscataquis County, and is the centerpiece of Bax ...

in Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

, a journey later recorded in "Ktaadn", the first part of ''The Maine Woods''.

Thoreau left Walden Pond on September 6, 1847. At Emerson's request, he immediately moved back to the Emerson house to help Emerson's wife, Lidian, manage the household while her husband was on an extended trip to Europe. Over several years, as he worked to pay off his debts, he continuously revised the manuscript of what he eventually published as '' Walden, or Life in the Woods'' in 1854, recounting the two years, two months, and two days he had spent at Walden Pond. The book compresses that time into a single calendar year, using the passage of the four seasons to symbolize human development. Part memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobi ...

and part spiritual quest, ''Walden'' at first won few admirers, but later critics have regarded it as a classic American work that explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models for just social and cultural conditions.

The American poet Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March26, 1874January29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in the United States. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloq ...

wrote of Thoreau, "In one book ... he surpasses everything we have had in America."

The American author John Updike

John Hoyer Updike (March 18, 1932 ŌĆō January 27, 2009) was an American novelist, poet, short-story writer, art critic, and literary critic. One of only four writers to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction more than once (the others being Booth ...

said of the book, "A century and a half after its publication, Walden has become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible."

Thoreau moved out of Emerson's house in July 1848 and stayed at a house on nearby Belknap Street. In 1850, he moved into a house at 255 Main Street, where he lived until his death.

In the summer of 1850, Thoreau and Channing journeyed from Boston to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montr├®al, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

and Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Qu├®bec), officially Qu├®bec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communaut├® m├®trop ...

. These would be Thoreau's only travels outside the United States. It is as a result of this trip that he developed lectures that eventually became ''A Yankee in Canada''. He jested that all he got from this adventure "was a cold". In fact, this proved an opportunity to contrast American civic spirit and democratic values with a colony apparently ruled by illegitimate religious and military power. Whereas his own country had had its revolution, in Canada history had failed to turn.

Later years, 1851ŌĆō1862

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and narratives of travel and expedition. He read avidly on

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and narratives of travel and expedition. He read avidly on botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

and often wrote observations on this topic into his journal. He admired William Bartram

William Bartram (April 20, 1739 ŌĆō July 22, 1823) was an American botanist, ornithologist, natural historian and explorer. Bartram was the author of an acclaimed book, now known by the shortened title ''Bartram's Travels'', which chronicled ...

and Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 ŌĆō 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

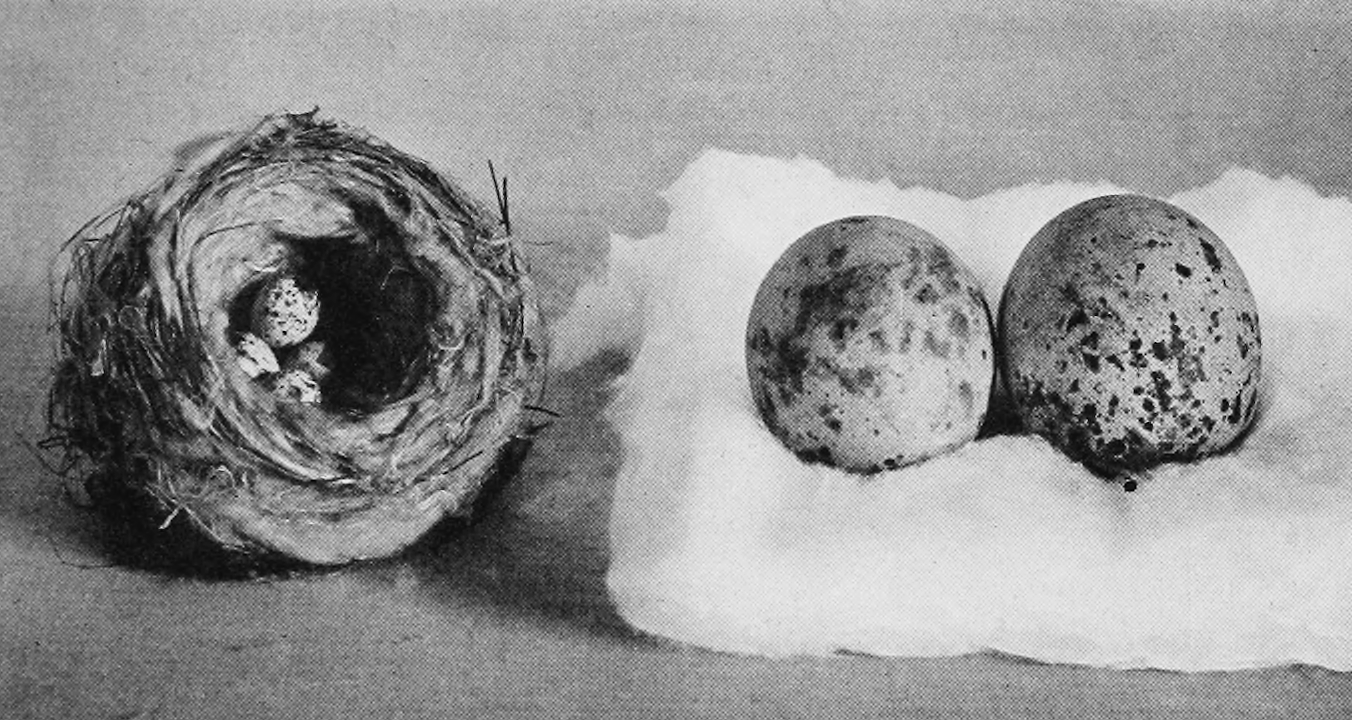

's '' Voyage of the Beagle''. He kept detailed observations on Concord's nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds migrated. The point of this task was to "anticipate" the seasons of nature, in his word.

He became a land surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is c ...

and continued to write increasingly detailed observations on the natural history of the town, covering an area of , in his journal, a two-million-word document he kept for 24 years. He also kept a series of notebooks, and these observations became the source of his late writings on natural history, such as "Autumnal Tints", "The Succession of Trees", and "Wild Apples", an essay lamenting the destruction of the local wild apple

''Malus sieversii'' is a wild apple native to the mountains of Central Asia in southern Kazakhstan. It has recently been shown to be the primary ancestor of most cultivars of the domesticated apple (''Malus domestica''). It was first described a ...

species.

With the rise of environmental history

Environmental history is the study of human interaction with the natural world over time, emphasising the active role nature plays in influencing human affairs and vice versa.

Environmental history first emerged in the United States out of th ...

and ecocriticism

Ecocriticism is the study of literature and ecology from an interdisciplinary point of view, where literature scholars analyze texts that illustrate environmental concerns and examine the various ways literature treats the subject of nature. It wa ...

as academic disciplines, several new readings of Thoreau began to emerge, showing him to have been both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in fields and woodlots. For instance, "The Succession of Forest Trees", shows that he used experimentation and analysis to explain how forests regenerate after fire or human destruction, through the dispersal of seeds by winds or animals. In this lecture, first presented to a cattle show in Concord, and considered his greatest contribution to ecology, Thoreau explained why one species of tree can grow in a place where a different tree did previously. He observed that squirrel

Squirrels are members of the family Sciuridae, a family that includes small or medium-size rodents. The squirrel family includes tree squirrels, ground squirrels (including chipmunks and prairie dogs, among others), and flying squirrels. Squ ...

s often carry nuts far from the tree from which they fell to create stashes. These seeds are likely to germinate and grow should the squirrel die or abandon the stash. He credited the squirrel for performing a "great service ... in the economy of the universe."

He traveled to

He traveled to Canada East

Canada East (french: links=no, Canada-Est) was the northeastern portion of the United Province of Canada. Lord Durham's Report investigating the causes of the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions recommended merging those two colonies. The new ...

once, Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

four times, and Maine three times; these landscapes inspired his "excursion" books, '' A Yankee in Canada'', ''Cape Cod'', and ''The Maine Woods'', in which travel itineraries frame his thoughts about geography, history and philosophy. Other travels took him southwest to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and New York City in 1854 and west across the Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational CanadianŌĆōAmerican region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin along with the Canadian p ...

in 1861, when he visited Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

, St. Paul

Paul; grc, ╬Ā╬▒ß┐”╬╗╬┐Žé, translit=Paulos; cop, Ō▓ĪŌ▓üŌ▓®Ō▓ŚŌ▓¤Ō▓ź; hbo, ūżūÉūĢū£ūĢūĪ ūöū®ū£ūÖūŚ (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, ž©┘ł┘äž│ ž¦┘äžĘž▒ž│┘łž│┘Ŗ; grc, ╬Ż╬▒ß┐”╬╗╬┐Žé ╬ż╬▒ŽüŽā╬ĄŽŹŽé, Sa┼®los Tarse├║s; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

and Mackinac Island

Mackinac Island ( ; french: ├Äle Mackinac; oj, Mishimikinaak ßÆźßöæßÆźßæŁßōłßÆā; otw, Michilimackinac) is an island and resort area, covering in land area, in the U.S. state of Michigan. The name of the island in Odawa is Michilimackinac an ...

. He was provincial in his own travels, but he read widely about travel in other lands. He devoured all the first-hand travel accounts available in his day, at a time when the last unmapped regions of the earth were being explored. He read Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fern├Żo de Magalh├Żes, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 ŌĆō 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the East ...

and James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October ŌĆō 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

; the arctic explorers John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 ŌĆō 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through ...

, Alexander Mackenzie and William Parry; David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 ŌĆō 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

and Richard Francis Burton

Sir Richard Francis Burton (; 19 March 1821 ŌĆō 20 October 1890) was a British explorer, writer, orientalist scholar,and soldier. He was famed for his travels and explorations in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, as well as his extraordinary kn ...

on Africa; Lewis and Clark

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

; and hundreds of lesser-known works by explorers and literate travelers. Astonishing amounts of reading fed his endless curiosity about the peoples, cultures, religions and natural history of the world and left its traces as commentaries in his voluminous journals. He processed everything he read, in the local laboratory of his Concord experience. Among his famous aphorisms is his advice to "live at home like a traveler".

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, many prominent voices in the abolitionist movement distanced themselves from Brown or damned him with faint praise. Thoreau was disgusted by this, and he composed a key speech, '' A Plea for Captain John Brown'', which was uncompromising in its defense of Brown and his actions. Thoreau's speech proved persuasive: the abolitionist movement began to accept Brown as a martyr, and by the time of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 ŌĆō May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

entire armies of the North were literally singing Brown's praises. As a biographer of Brown put it, "If, as Alfred Kazin suggests, without John Brown there would have been no Civil War, we would add that without the Concord Transcendentalists, John Brown would have had little cultural impact."

Death

Thoreau contractedtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in 1835 and suffered from it sporadically afterwards. In 1860, following a late-night excursion to count the rings of tree stumps during a rainstorm, he became ill with bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

. His health declined, with brief periods of remission, and he eventually became bedridden. Recognizing the terminal nature of his disease, Thoreau spent his last years revising and editing his unpublished works, particularly ''The Maine Woods'' and ''Excursions'', and petitioning publishers to print revised editions of ''A Week'' and ''Walden''. He wrote letters and journal entries until he became too weak to continue. His friends were alarmed at his diminished appearance and were fascinated by his tranquil acceptance of death. When his aunt Louisa asked him in his last weeks if he had made his peace with God, Thoreau responded, "I did not know we had ever quarreled."

Aware he was dying, Thoreau's last words were "Now comes good sailing", followed by two lone words, "moose" and "Indian". He died on May 6, 1862, at age 44.

Aware he was dying, Thoreau's last words were "Now comes good sailing", followed by two lone words, "moose" and "Indian". He died on May 6, 1862, at age 44. Amos Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 ŌĆō March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and a ...

planned the service and read selections from Thoreau's works, and Channing presented a hymn. Emerson wrote the eulogy spoken at the funeral. Thoreau was buried in the Dunbar family plot; his remains and those of members of his immediate family were eventually moved to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, is the final resting place of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is set in the adjacent burying ground at the Old Dutch C ...

in Concord, Massachusetts.

Nature and human existence

Thoreau was an early advocate of recreational hiking andcanoeing

Canoeing is an activity which involves paddling a canoe with a single-bladed paddle. Common meanings of the term are limited to when the canoeing is the central purpose of the activity. Broader meanings include when it is combined with other acti ...

, of conserving natural resources on private land, and of preserving wilderness as public land. He was himself a highly skilled canoeist; Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 ŌĆō May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

, after a ride with him, noted that "Mr. Thoreau managed the boat so perfectly, either with two paddles or with one, that it seemed instinct with his own will, and to require no physical effort to guide it."

He was not a strict vegetarian, though he said he preferred that diet and advocated it as a means of self-improvement. He wrote in ''Walden'', "The practical objection to animal food in my case was its uncleanness; and besides, when I had caught and cleaned and cooked and eaten my fish, they seemed not to have fed me essentially. It was insignificant and unnecessary, and cost more than it came to. A little bread or a few potatoes would have done as well, with less trouble and filth."Cheever, Susan (2006). ''American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau; Their Lives, Their Loves, Their Work''. Detroit: Thorndike Press. Large print edition. p. 241. .

Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead he sought a middle ground, the

Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead he sought a middle ground, the pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

realm that integrates nature and culture. His philosophy required that he be a didactic arbitrator between the wilderness he based so much on and the spreading mass of humanity in North America. He decried the latter endlessly but felt that a teacher needs to be close to those who needed to hear what he wanted to tell them. The wildness he enjoyed was the nearby swamp or forest, and he preferred "partially cultivated country". His idea of being "far in the recesses of the wilderness" of Maine was to "travel the logger's path and the Indian trail", but he also hiked on pristine land. In the essay "Henry David Thoreau, Philosopher" Roderick Nash

Roderick Frazier Nash is a professor emeritus of history and environmental studies at the University of California Santa Barbara. He was the first person to descend the Tuolumne River using a raft.

Scholarly biography

Nash received his Bache ...

wrote, "Thoreau left Concord in 1846 for the first of three trips to northern Maine. His expectations were high because he hoped to find genuine, primeval America. But contact with real wilderness in Maine affected him far differently than had the idea of wilderness in Concord. Instead of coming out of the woods with a deepened appreciation of the wilds, Thoreau felt a greater respect for civilization and realized the necessity of balance."

Of alcohol, Thoreau wrote, "I would fain keep sober always. ... I believe that water is the only drink for a wise man; wine is not so noble a liquor. ... Of all ebriosity, who does not prefer to be intoxicated by the air he breathes?"

Sexuality

Thoreau never married and was childless. In 1840, when he was 23, he proposed to eighteen-year old Ellen Sewall, but she refused him, on the advice of her father. Thoreau's sexuality has long been the subject of speculation, including by his contemporaries. Critics have called him heterosexual,homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

, or asexual. There is no evidence to suggest he had physical relations with anyone, man or woman. Some scholars have suggested that homoerotic sentiments run through his writings and concluded that he was homosexual.Harding, Walter (1991). "Thoreau's Sexuality". ''Journal of Homosexuality'' 21.3. pp. 23ŌĆō45. The elegy "Sympathy" was inspired by the eleven-year-old Edmund Sewall, who had just spent five days in the Thoreau household in 1839. One scholar has suggested that he wrote the poem to Edmund because he could not bring himself to write it to Edmund's sister Anna, and another that Thoreau's "emotional experiences with women are memorialized under a camouflage of masculine pronouns", but other scholars dismiss this. It has been argued that the long paean in ''Walden'' to the French-Canadian woodchopper Alek Therien, which includes allusions to Achilles and Patroclus

The relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is a key element of the stories associated with the Trojan War. Its exact natureŌĆöwhether homosexual, a non-sexual deep friendship, or something else entirelyŌĆöhas been a subject of dispute in bot ...

, is an expression of conflicted desire. In some of Thoreau's writing there is the sense of a secret self. In 1840 he writes in his journal: "My friend is the apology for my life. In him are the spaces which my orbit traverses". Thoreau was strongly influenced by the moral reformers of his time, and this may have instilled anxiety and guilt over sexual desire.

Politics

Thoreau was fervently against

Thoreau was fervently against slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slaveŌĆösomeone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and actively supported the abolitionist movement. He participated as a conductor in the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

, delivered lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

, and in opposition to the popular opinion of the time, supported radical abolitionist militia leader John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800ŌĆō1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763ŌĆō1842), Ir ...

and his party. Two weeks after the ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry and in the weeks leading up to Brown's execution, Thoreau delivered a speech to the citizens of Concord, Massachusetts, in which he compared the American government to Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (; grc-gre, ╬ĀŽī╬ĮŽä╬╣╬┐Žé ╬Ā╬╣╬╗ߊȎä╬┐Žé, ) was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of J ...

and likened Brown's execution to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and consider ...

:

In ''The Last Days of John Brown

"The Last Days of John Brown" is an essay by Henry David Thoreau, written in 1860, that praised the executed abolitionist militia leader John Brown.

See also

* "A Plea for Captain John Brown

"A Plea for Captain John Brown" is an essay by ...

'', Thoreau described the words and deeds of John Brown as noble and an example of heroism.The Last Days of John Brownfrom the Writings of Henry David Thoreau: The Digital Collection In addition, he lamented the newspaper editors who dismissed Brown and his scheme as "crazy". Thoreau was a proponent of

limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal Theo ...

and individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

. Although he was hopeful that mankind could potentially have, through self-betterment, the kind of government which "governs not at all", he distanced himself from contemporary "no-government men" (anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

), writing: "I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government."

Thoreau deemed the evolution from absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

to limited monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

to democracy

Democracy (From grc, ╬┤╬Ę╬╝╬┐╬║Žü╬▒Žä╬»╬▒, d─ōmokrat├Ła, ''d─ōmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

as "a progress toward true respect for the individual" and theorized about further improvements "towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man". Echoing this belief, he went on to write: "There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly."

It is on this basis that Thoreau could so strongly inveigh against the British administration and Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in ''A Yankee in Canada''. Despotic authority, Thoreau argued, had crushed the people's sense of ingenuity and enterprise; the Canadian ''habitants'' had been reduced, in his view, to a perpetual childlike state. Ignoring the recent rebellions, he argued that there would be no revolution in the St. Lawrence River valley.

Although Thoreau believed resistance to unjustly exercised authority could be both violent (exemplified in his support for John Brown) and nonviolent (his own example of tax resistance

Tax resistance is the refusal to pay tax because of opposition to the government that is imposing the tax, or to government policy, or as opposition to taxation in itself. Tax resistance is a form of direct action and, if in violation of the tax ...

displayed in ''Resistance to Civil Government''), he regarded pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

nonresistance as temptation to passivity,The Servicefrom the Writings of Henry David Thoreau: The Digital Collection writing: "Let not our Peace be proclaimed by the rust on our swords, or our inability to draw them from their scabbards; but let her at least have so much work on her hands as to keep those swords bright and sharp." Furthermore, in a formal lyceum debate in 1841, he debated the subject "Is it ever proper to offer forcible resistance?", arguing the affirmative. Likewise, his condemnation of the

MexicanŌĆōAmerican War

The MexicanŌĆōAmerican War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

did not stem from pacifism, but rather because he considered Mexico "unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army" as a means to expand the slave territory.

Thoreau was ambivalence, ambivalent towards industrialization and capitalism. On one hand he regarded commerce as "unexpectedly confident and serene, adventurous, and unwearied" and expressed admiration for its associated cosmopolitanism, writing:

On the other hand, he wrote disparagingly of the factory system:

Thoreau also favored bioregionalism, the protection of animals and wild areas, free trade, and taxation for schools and highways. He disapproved of the subjugation of Native Americans, slavery, technological utopianism, consumerism, philistinism, mass entertainment, and frivolous applications of technology.

Intellectual interests, influences, and affinities

Indian sacred texts and philosophy