Henry B. Brown on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

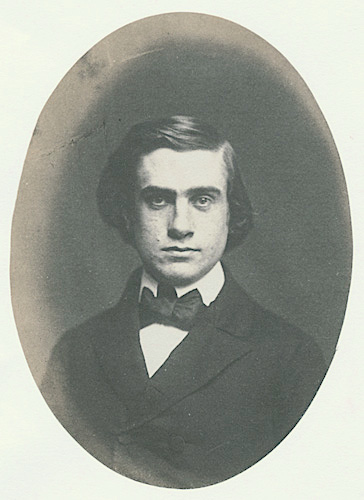

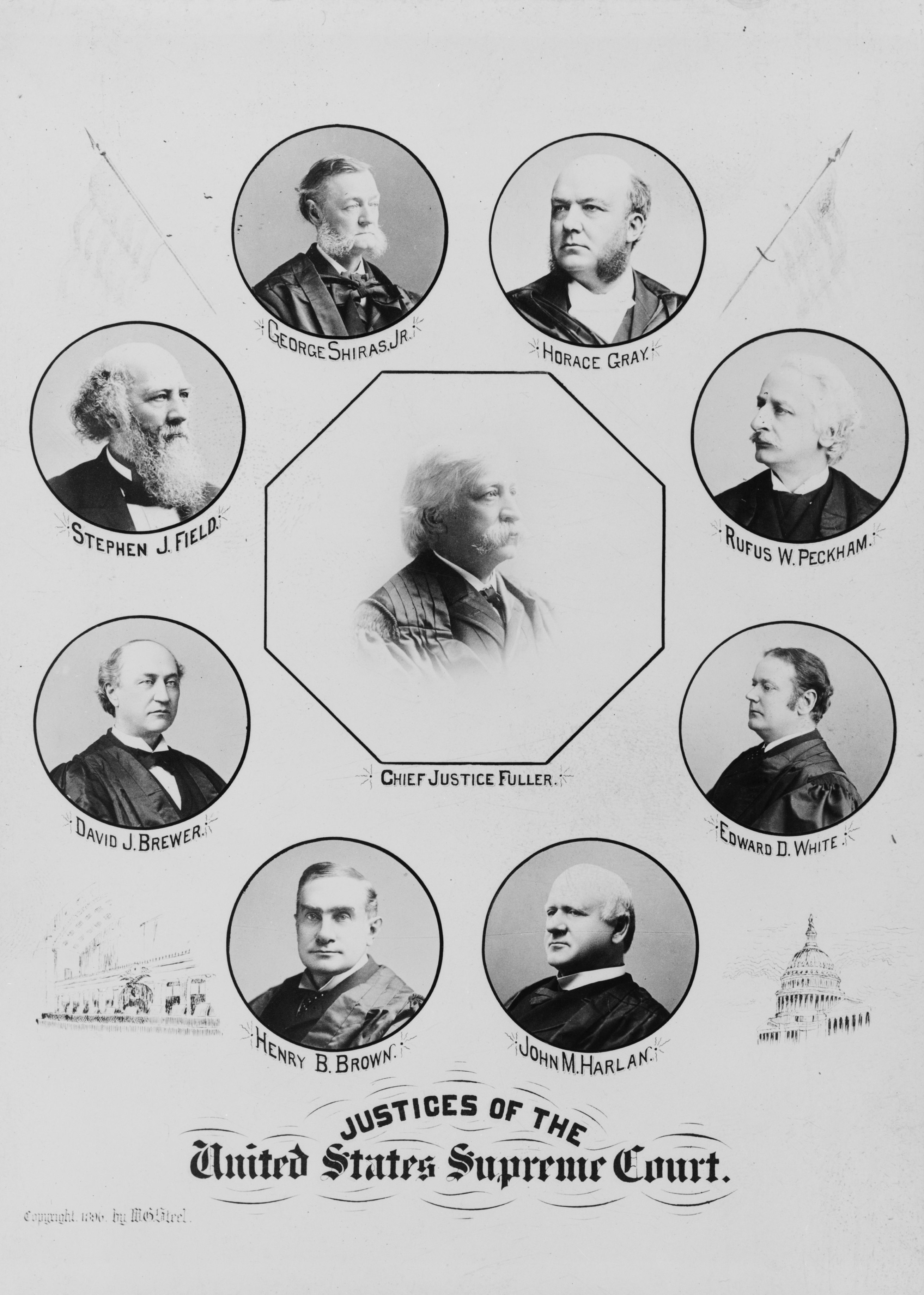

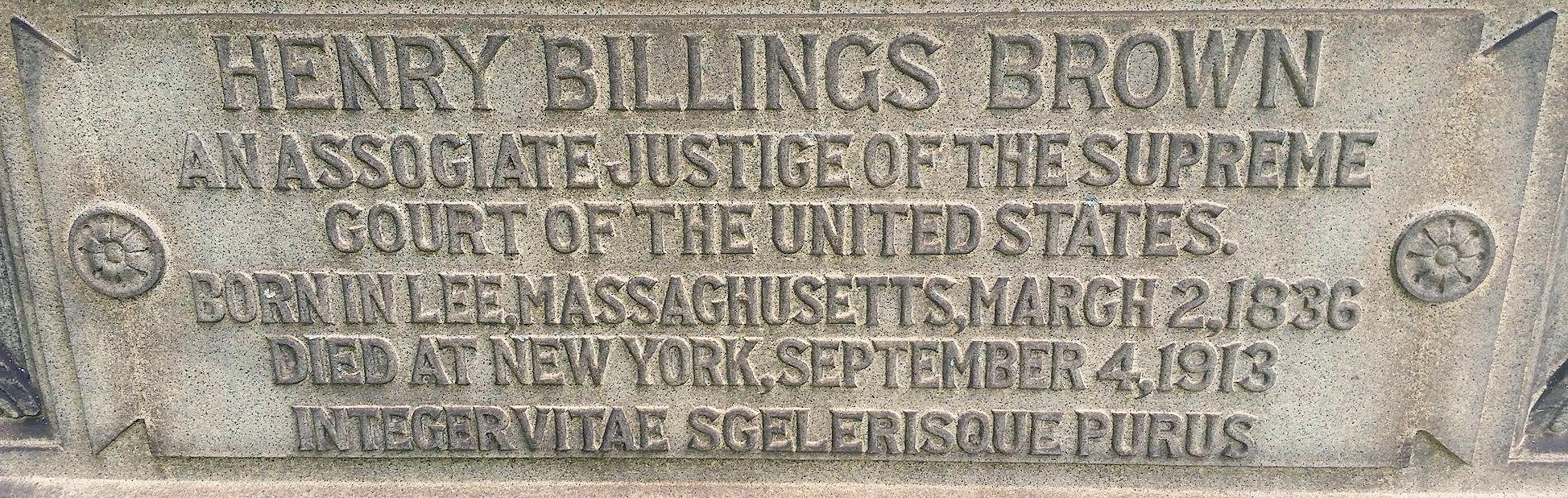

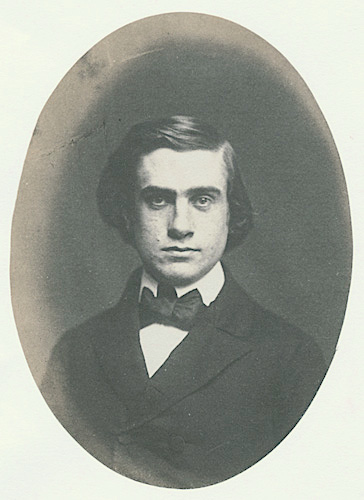

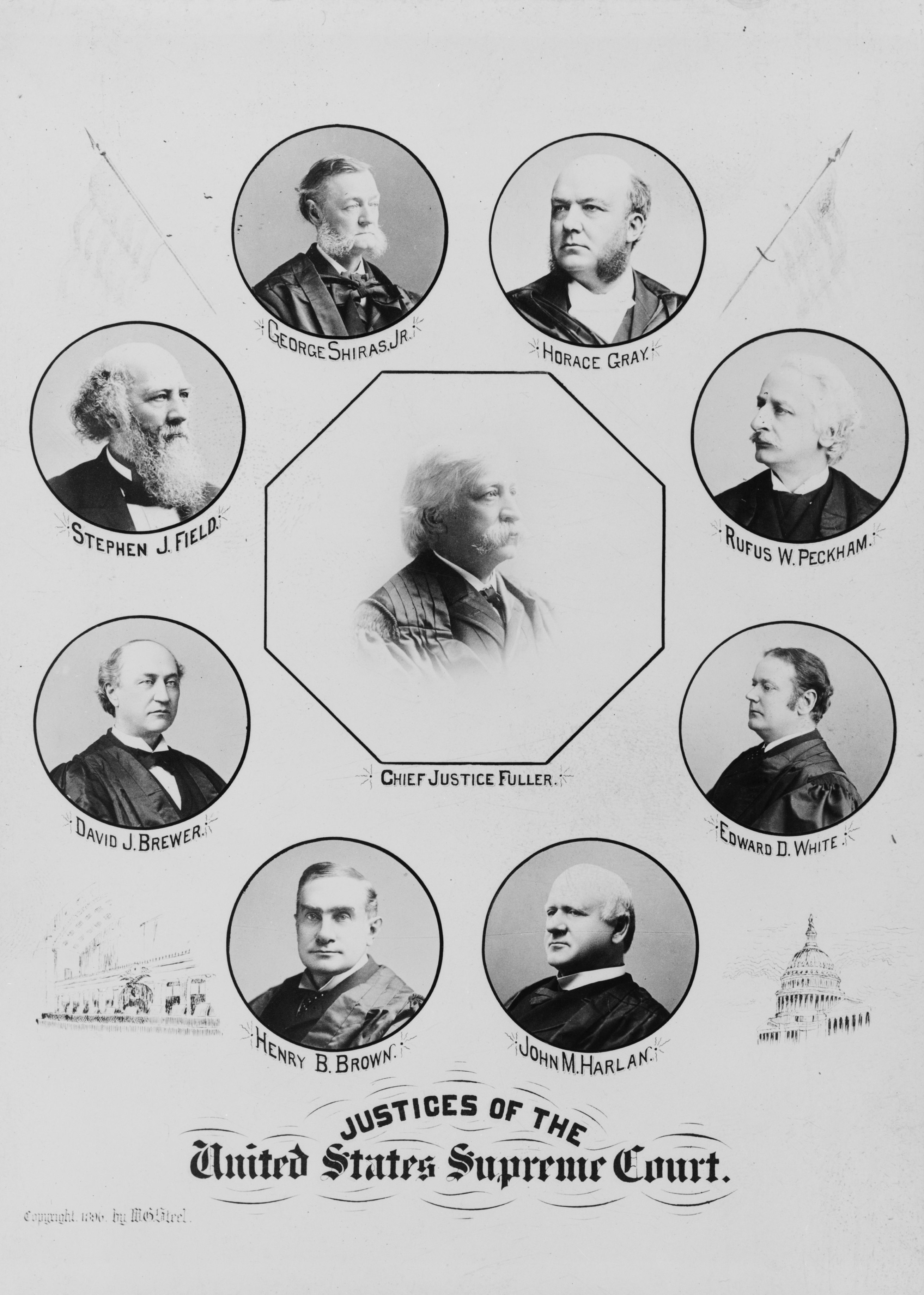

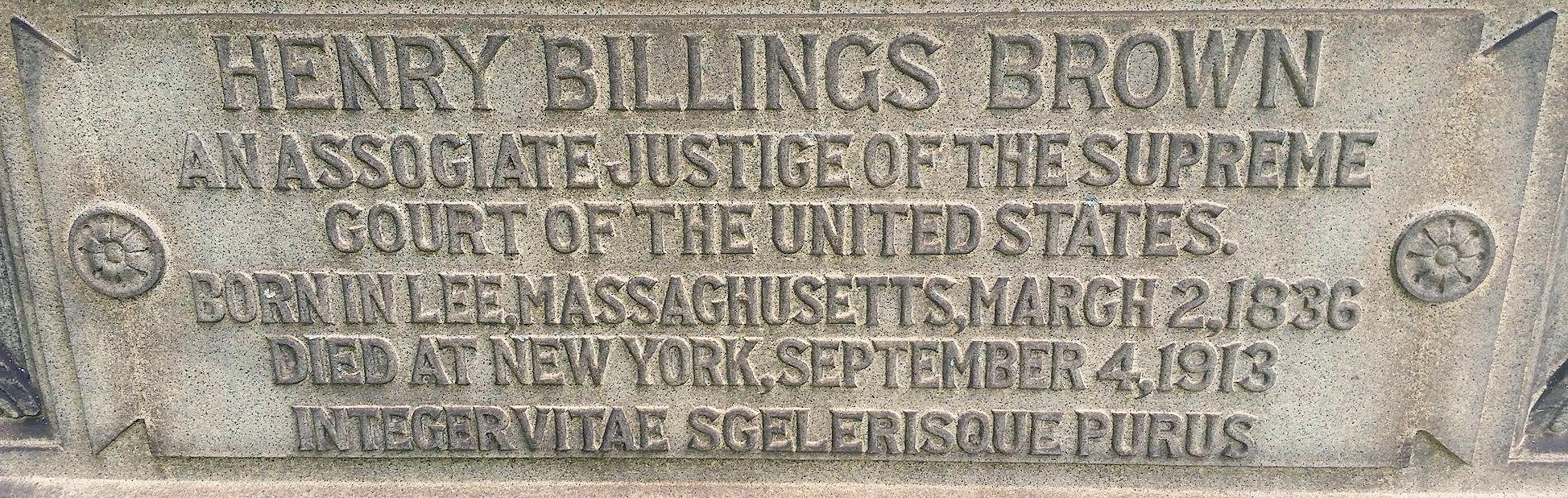

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1891 to 1906.

Although a respected lawyer and U.S. District Judge before ascending to the high court, Brown is harshly criticized for writing the majority opinion in ''

Brown was born in South Lee, Massachusetts, the son of Mary Tyler and Billings Brown, and grew up in

Brown was born in South Lee, Massachusetts, the son of Mary Tyler and Billings Brown, and grew up in

Admitted to the Michigan Bar in 1860, Brown's early law practice was in

Admitted to the Michigan Bar in 1860, Brown's early law practice was in

Brown was nominated by President

Brown was nominated by President

Brown is best known, and widely criticized, for the 1896 decision in ''

Brown is best known, and widely criticized, for the 1896 decision in ''

File:Toutorsky Mansion.JPG, House of Justice Henry Billings Brown in Washington, D.C.

File:Justice Brown's residence, Washington, D.C. LCCN2001698379.jpg, Justice Brown's residence around 1895

In 1891 he paid $25,000 () to the Riggs family for land at 1720 16th Street, NW, in

Brown died of heart disease on September 4, 1913, at a hotel in Bronxville, New York. He is buried next to his first wife in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

Brown died of heart disease on September 4, 1913, at a hotel in Bronxville, New York. He is buried next to his first wife in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

The Character and Services of James Valentine Campbell, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the States of Michigan

'. Delivered at the request of the Detroit Bar Association, 1890. *

The Dissenting Opinions of Mr. Justice Daniel

'. 24 Am. L. Rev. 869 (1887). *''The Dissenting Opinions of Mr. Justice Harlan''. 46 Am. L. Rev. 321 (1912). *''The Distribution of Property'', in Report of the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the

Federal Law and Federal Courts.

' 11 Library Am. L. & Practice 323 (1912). *

International Courts

'' 20 Yale L.J. 1 (1910). *''Judicial Independence'', in Report of the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the American Bar Association, 265 (1889). *''Judicial Treatment of Criminal Offenders.'' 17 Chicago Legal News 171 (1910). *

Jurisdiction of the Admiralty in Cases of Tort

'' 9 Columbia L. Rev. 1 (1909). *''Lake Erie Piracy Case.'' 21 Green Bag 143 (1909). *''Law and Procedure in Divorce.'' 44 Am. L. Rev. 321 (1910). *''Liberty of the Press.'' 23 Proc. N.Y. St. Bar Ass'n 130 (1900). *''The New Federal Judicial Code,'' in Report of the Thirty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the American Bar Association, 339 (1911). *''Proposed International Prize Court.'' 2 Am. J. Int. L. 476 (1908).

Reports of Admiralty and Revenue Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States, for the Western Lake and River Districts

New York: Baker, Voorhies & Co., 1876. *

The Status of the Automobile

'' 17 Yale L.J. 223 (1908). *

The Twentieth Century. An address delivered before the graduating classes at the seventy-first anniversary of Yale Law School, on June 24th, 1895

'. New Haven: Hoggson & Robinson (1895).

''Woman Suffrage; a paper read by ex-Justice Brown ... before the Ladies Congressional Club of Washington D.C. Boston: Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women'' (1910)

Federal Judicial Center biography

Photograph, Henry Billings Brown Home, Washington, D.C.

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, Henry Billings 1836 births 1913 deaths 19th-century American judges 20th-century American judges American Congregationalists Burials at Elmwood Cemetery (Detroit) Death in New York (state) Harvard Law School alumni Judges of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan Michigan lawyers Michigan Republicans People from Lee, Massachusetts People from Berkshire County, Massachusetts People from Detroit People from Wayne County, Michigan Lawyers from Detroit United States federal judges appointed by Benjamin Harrison United States federal judges appointed by Ulysses S. Grant Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States University of Michigan Law School faculty Washington, D.C., Republicans Yale College alumni Yale University alumni Yale Law School alumni Georgetown University Law Center faculty Wayne State University faculty Wayne State University people Assistant United States Attorneys

Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'', widely regarded as one of the most ill-considered decisions ever issued by the Court, which upheld the legality of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in public transport

Public transport (also known as public transportation, public transit, mass transit, or simply transit) is a system of transport for passengers by group travel systems available for use by the general public unlike private transport, typi ...

ation. ''Plessy'' legitimized existing state laws establishing racial segregation, and provided an impetus for later segregation statutes. Legislative achievements won during the Reconstruction Era were erased through ''Plessy's'' "separate but equal" doctrine.

Brown has mostly been forgotten, or remembered only in derision for his obtuse statements in the ''Plessy'' opinion, such as his frequently-ridiculed rejection of a claim that the Louisiana segregation statute at issue "stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so rown wrote it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it."

Early career

Family and education

Brown was born in South Lee, Massachusetts, the son of Mary Tyler and Billings Brown, and grew up in

Brown was born in South Lee, Massachusetts, the son of Mary Tyler and Billings Brown, and grew up in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

. His was a New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

merchant family. He attended Monson Academy, Monson, MA and entered Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

at 16. There he was a member of Alpha Delta Phi fraternity and was elected to membership in Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

. He earned a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four year ...

degree there in 1856. Among his undergraduate classmates were Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, as ...

, later a U.S. Senator from New York, and David Josiah Brewer

David Josiah Brewer (June 20, 1837 – March 28, 1910) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1890 to 1910. An appointee of President Benjamin Harrison, he supported states' righ ...

, who became Brown's colleague on the Supreme Court. Depew roomed across the hall from Brown for three years in Old North Middle Hall, and remembered "a feminine quality bout Brownwhich led to his being called Henrietta" by classmates in his all-male college. After a yearlong tour of Europe, Brown studied law with Judge John H. Brockway

John Hall Brockway (January 31, 1801 – July 29, 1870) was a U.S. Representative from Connecticut.

Biography

Born the son of the Reverend Diodate and Miranda Hall Brockway in Ellington, Connecticut, Brockway pursued preparatory studies and w ...

in Ellington, Connecticut

Ellington is a town in Tolland County, Connecticut, United States. Ellington was incorporated in May 1786, from East Windsor. As of the 2020 census, the town population was 16,426.

History

Originally the area in what is now Ellington was named ...

, but his refusal to participate in a local religious revival made life there unpleasant for him. He left Ellington to pursue legal studies, with a year at Yale Law School

Yale Law School (Yale Law or YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824 and has been ranked as the best law school in the United States by '' U.S. News & Worl ...

, and a semester at Harvard Law School.

Legal activities in Detroit

Admitted to the Michigan Bar in 1860, Brown's early law practice was in

Admitted to the Michigan Bar in 1860, Brown's early law practice was in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

, where he specialized in admiralty law as it applied to shipping on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

. In addition to his private law practice, at times between 1861 and 1868 Brown served as Deputy U.S. Marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforce ...

, Assistant United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

, and to fill an opening was appointed judge of the Wayne County Circuit Court in Detroit, although he only served briefly in that position and lost an election for a full term. He then became a partner specializing in admiralty law in the firm of Newberry, Pond & Brown, and practiced there for seven years. In 1872 Brown failed in an attempt to win the Republican nomination for a congressional seat.

Personal life

In 1864, Brown married Caroline Pitts, the daughter of a wealthy Michiganlumber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

merchant. They had no children. He did not serve in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, but like many well-to-do men instead hired a substitute soldier to take his place.

Brown kept diaries from his college days until his appointment as a federal judge in 1875. Now held in the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library

The Detroit Public Library is the second largest library system in the U.S. state of Michigan by volumes held (after the University of Michigan Library) and the 21st-largest library system (and the fourth-largest public library system) in the Uni ...

, they suggest that he was both genial and ambitious, but also depressed and doubtful about himself. As a child Brown attended his family's Congregational Church, and when married to his first wife he accompanied her to a Presbyterian Church, but he was generally uninterested in religious matters.

Federal judicial service

District court service

Appointment

The death of Brown's father-in-law left Brown and his wife financially independent, so he was willing to accept the relatively low salary of a federal judge. On March 17, 1875, Brown was nominated by PresidentUlysses Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

to a seat on the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan (in case citations, E.D. Mich.) is the federal district court with jurisdiction over of the eastern half of the Lower Peninsula of the State of Michigan. The Court is based ...

left vacant by the death of John Wesley Longyear. Brown was confirmed

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

two days later and immediately received his commission.

Publishing and teaching

Brown edited a collection of rulings and orders in important admiralty cases from inland waters, and later compiled a case book on admiralty law for lectures atGeorgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

. He also taught admiralty law classes at the University of Michigan Law School

The University of Michigan Law School (Michigan Law) is the law school of the University of Michigan, a public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Founded in 1859, the school offers Master of Laws (LLM), Master of Comparative Law (MCL ...

from 1860 to 1875, and medical jurisprudence

Medical jurisprudence or legal medicine is the branch of science and medicine involving the study and application of scientific and medical knowledge to legal problems, such as inquests, and in the field of law. As modern medicine is a legal ...

at the Detroit Medical College

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

(now the medical school of Wayne State University

Wayne State University (WSU) is a public research university in Detroit, Michigan. It is Michigan's third-largest university. Founded in 1868, Wayne State consists of 13 schools and colleges offering approximately 350 programs to nearly 25,000 ...

) from 1868 to 1871. Brown received honorary doctoral degrees from the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

in 1887, and from Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

in 1891.

Supreme Court

Appointment

Brown was nominated by President

Brown was nominated by President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

as an associate justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

on December 23, 1890, to succeed Samuel Freeman Miller

Samuel Freeman Miller (April 5, 1816 – October 13, 1890) was an American lawyer and physician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1862 until his death in 1890.

Early life, education, and medical career

Born ...

. Harrison, who had earlier considered Brown for a Supreme Court appointment following the death of Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews, CBE (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English footballer who played as an outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the British game, he is the only player to have been knighted while sti ...

the previous year, actively lobbied senators on Brown's behalf. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate by voice vote on December 29, 1890, and was sworn into office on January 5, 1891. In an autobiographical essay, Brown commented "While I had been much attached to Detroit and its people, there was much to compensate me in my new sphere of activity. If the duties of the new office were not so congenial to my taste as those of district judge, it was a position of far more dignity, was better paid and was infinitely more gratifying to one's ambition."

Jurisprudence

As a jurist, Brown was generally against government intervention in business, and joined the majority opinion in '' Lochner v. New York'' (1905) striking down a limitation on maximum working hours. He did, however, support thefederal income tax

Income taxes in the United States are imposed by the federal government, and most states. The income taxes are determined by applying a tax rate, which may increase as income increases, to taxable income, which is the total income less allow ...

in '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'' (1895), and wrote for the Court in '' Holden v. Hardy'' (1898), upholding a Utah law restricting male miners to an eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

.

=''Plessy v. Ferguson''

= Brown is best known, and widely criticized, for the 1896 decision in ''

Brown is best known, and widely criticized, for the 1896 decision in ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'', in which he wrote the majority opinion upholding the principle and legitimacy of "separate but equal" facilities for American blacks and whites. In his opinion, Brown argued that the recognition of racial difference did not necessarily violate constitutional principle. As long as equal facilities and services were available to all citizens, the "commingling of the two races" need not be enforced. ''Plessy'', which provided legal support for the system of Jim Crow Laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

, was effectively overruled by the Court in ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' in 1954. When issued, ''Plessy'' attracted relatively little attention, but in the late 20th century it came to be condemned, with maledictions falling on Brown for having written it.

=Insular Cases

= Justice Brown authored the Court's 1901 opinions in '' DeLima v. Bidwell'' and ''Downes v. Bidwell

''Downes v. Bidwell'', 182 U.S. 244 (1901), was a case in which the US Supreme Court decided whether US territories were subject to the provisions and protections of the US Constitution. The issue is sometimes stated as whether the Constitution fo ...

'', two of the Insular Cases

The Insular Cases are a series of opinions by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1901 about the status of U.S. territories acquired in the Spanish–American War. Some scholars also include cases regarding territorial status decided up unt ...

, considering the status of territories acquired by the U.S. in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

of 1898.

=''Hale v. Henkel''

= Brown expounded for the majority the powers accorded to the grand jury in '' Hale v. Henkel'', a 1906 case where the defendant—a tobacco company executive—refused to testify to the grand jury on several grounds in a case based upon theSherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

...

. This opinion, said to be among his best, was rendered March 12, 1906, only 10 weeks before his retirement.

Personal life in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, hired architect William Henry Miller, and built a five-story, 18-room mansion for $40,000 (). He would live in this house, later known as the Toutorsky Mansion

The Toutorsky Mansion, also called the Brown-Toutorsky House, is a five-story, 18-room house located at 1720 16th Street, NW in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Since 2012, it has housed the Embassy of the Republic of the Con ...

, until his death. Ironically—in light of Brown's racial attitudes—the house is now the embassy of the Republic of the Congo.

Brown's wife Caroline died in 1901. Three years later, Brown married a close friend of hers, the widow Josephine E. Tyler, who survived him.

Retirement

Near the end of his years on the Court, Brown largely lost his eyesight. He retired from the Court on May 28, 1906, at the age of 70.Women's suffrage

In April 1910, retired Justice Brown presented a talk to The Ladies' Congressional Club of Washington, D.C., entitled "Woman Suffrage". In it he advocated against extending the vote to women, arguing that no persons, male or female, have a natural right to the vote, and that for a litany of reasons women should not have the legal ability to participate in elections. From the perspective of the 21st century, the talk is full of risible assertions and clichés about the role of women in society.Death

Brown died of heart disease on September 4, 1913, at a hotel in Bronxville, New York. He is buried next to his first wife in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

Brown died of heart disease on September 4, 1913, at a hotel in Bronxville, New York. He is buried next to his first wife in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

Legacy

Decisions concerning minority groups

Despite ''Plessy v. Ferguson,'' Brown as a judge did not invariably vote against the interests of minority litigants. For example, in '' Ward v. Race Horse'', Brown was the sole dissenter when the Court held that tribal hunting rights granted under an 1869 treaty with the Bannock Indians must yield to a state law prohibiting them. As to theChinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

, Brown voted with the majority in '' United States v. Wong Kim Ark'' that a child born in the United States of Chinese parents was a U.S. citizen under the Citizenship Clause

The Citizenship Clause is the first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was adopted on July 9, 1868, which states:

This clause reversed a portion of the ''Dred Scott v. Sandford'' decision, which had d ...

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Brown also voted with the majority in ''Wong Wing v. United States,'' in holding that Chinese persons allegedly in the United States illegally may not be imprisoned at hard labor without a trial pending deportation. Brown also joined Justice David Brewer's dissent in '' Giles v. Harris'', arguing Black Americans had a right to challenge voter suppression in federal court.

Abilities

Brown has been remembered as "a capable and solid, if unimaginative, legal technician." One of his friends offered the faint praise that Brown's life "shows how a man without perhaps extraordinary abilities may attain and honour the highest judicial position by industry, by good character, pleasant manners and some aid from fortune". His obituary in the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' stated that on the Supreme Court Brown "gained a reputation for the strictest impartiality"; that he was "courteous to counsel", "was noted for his willingness to admit that he had committed an error", and finally that "he was remarkably free from pride of opinion".

Elena Kagan confirmation hearing

Perhaps the public nadir of Brown's legacy occurred during the 2010Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

confirmation hearings for then Solicitor General, and former Harvard Law School Dean, Elena Kagan, to be an associate justice of the Supreme Court. Kagan admitted that she did not know who Brown was, and her questioner, Republican Senator Lindsey Graham

Lindsey Olin Graham (born July 9, 1955) is an American lawyer and politician serving as the senior United States senator from South Carolina, a seat he has held since 2003. A member of the Republican Party, Graham chaired the Senate Committee on ...

of South Carolina, then mentioned Brown with disdain:

Absence of memorials

ALiberty ship

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Ma ...

named after him, the '' Henry B. Brown'' (hull number 938), was launched in 1943 and scrapped in 1965.

Apart from a sepulchral monument in a Detroit cemetery, there are no known statues, named schools or buildings or institutions, or any other memorials to Brown. There has been no book-length biography published about him.

Brown's non-judicial bibliography

*Cases on the Law of Admiralty. St. Paul, Minn.: West Publishing Co., 1896. *The Character and Services of James Valentine Campbell, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the States of Michigan

'. Delivered at the request of the Detroit Bar Association, 1890. *

The Dissenting Opinions of Mr. Justice Daniel

'. 24 Am. L. Rev. 869 (1887). *''The Dissenting Opinions of Mr. Justice Harlan''. 46 Am. L. Rev. 321 (1912). *''The Distribution of Property'', in Report of the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

, 213 (1893).

*Federal Law and Federal Courts.

' 11 Library Am. L. & Practice 323 (1912). *

International Courts

'' 20 Yale L.J. 1 (1910). *''Judicial Independence'', in Report of the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the American Bar Association, 265 (1889). *''Judicial Treatment of Criminal Offenders.'' 17 Chicago Legal News 171 (1910). *

Jurisdiction of the Admiralty in Cases of Tort

'' 9 Columbia L. Rev. 1 (1909). *''Lake Erie Piracy Case.'' 21 Green Bag 143 (1909). *''Law and Procedure in Divorce.'' 44 Am. L. Rev. 321 (1910). *''Liberty of the Press.'' 23 Proc. N.Y. St. Bar Ass'n 130 (1900). *''The New Federal Judicial Code,'' in Report of the Thirty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the American Bar Association, 339 (1911). *''Proposed International Prize Court.'' 2 Am. J. Int. L. 476 (1908).

Reports of Admiralty and Revenue Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States, for the Western Lake and River Districts

New York: Baker, Voorhies & Co., 1876. *

The Status of the Automobile

'' 17 Yale L.J. 223 (1908). *

The Twentieth Century. An address delivered before the graduating classes at the seventy-first anniversary of Yale Law School, on June 24th, 1895

'. New Haven: Hoggson & Robinson (1895).

''Woman Suffrage; a paper read by ex-Justice Brown ... before the Ladies Congressional Club of Washington D.C. Boston: Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women'' (1910)

See also

*List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight associate justices, any six of ...

* List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

A total of 116 people have served on the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest judicial body in the United States, since it was established in 1789. Supreme Court justices have life tenure, and so they serve until they die, resign, reti ...

* List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 4)

Law clerks have assisted the justices of the United States Supreme Court in various capacities since the first one was hired by Justice Horace Gray in 1882. Each Associate Justice is permitted to employ four law clerks per Court term; the Chie ...

* List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Fuller Court

This is a partial chronological list of cases decided by the United States Supreme Court during the Fuller Court, the tenure of Chief Justice Melville Weston Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was a ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Kermit L. Hall (ed.), ''Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States'', 2nd edition, 2005 () * Robert J. Glennon Jr., ''Justice Henry Billings Brown: Values in Tension'',University of Colorado Law Review

The University of Colorado Law School is one of the professional graduate schools within the University of Colorado System. It is a public law school, with more than 500 students attending and working toward a Juris Doctor or Master of Studies in ...

44 (1973): 553–604

*

* ''Memoir of Henry Billings Brown'', by Charles A. Kent of the Detroit Bar, 1915 ()

External links

Federal Judicial Center biography

Photograph, Henry Billings Brown Home, Washington, D.C.

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, Henry Billings 1836 births 1913 deaths 19th-century American judges 20th-century American judges American Congregationalists Burials at Elmwood Cemetery (Detroit) Death in New York (state) Harvard Law School alumni Judges of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan Michigan lawyers Michigan Republicans People from Lee, Massachusetts People from Berkshire County, Massachusetts People from Detroit People from Wayne County, Michigan Lawyers from Detroit United States federal judges appointed by Benjamin Harrison United States federal judges appointed by Ulysses S. Grant Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States University of Michigan Law School faculty Washington, D.C., Republicans Yale College alumni Yale University alumni Yale Law School alumni Georgetown University Law Center faculty Wayne State University faculty Wayne State University people Assistant United States Attorneys