Henry Allan Fagan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

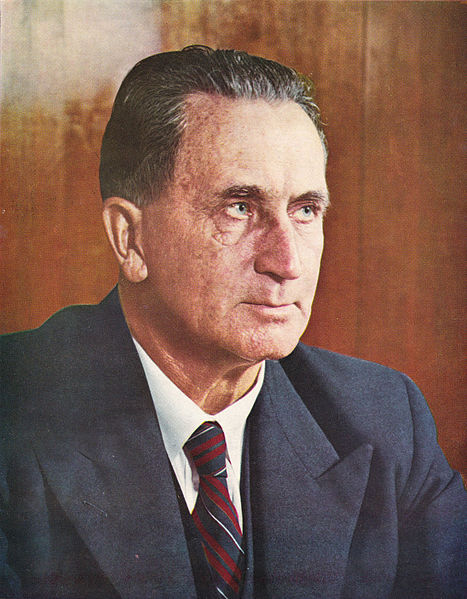

Henry Allan Fagan, KC (4 April 1889 – 6 December 1963) was the

In 1919, Fagan left ''Die Burger'' and became, for a brief period, the first

In 1919, Fagan left ''Die Burger'' and became, for a brief period, the first

Thus, although Fagan had been in the vanguard of the Afrikaner nationalist movement and began and ended his political career as a colleague of Malan's, he "was not a Malanite" and differed in crucial respects, and at crucial historical moments, from the post-Hertzog National Party. The best-known instance would be his report for the Native Laws Commission (commonly called the Fagan Commission), which recommended a gradual liberalisation of South Africa's system of

Thus, although Fagan had been in the vanguard of the Afrikaner nationalist movement and began and ended his political career as a colleague of Malan's, he "was not a Malanite" and differed in crucial respects, and at crucial historical moments, from the post-Hertzog National Party. The best-known instance would be his report for the Native Laws Commission (commonly called the Fagan Commission), which recommended a gradual liberalisation of South Africa's system of

Nevertheless, the Commission had firmly rejected the principles on which the National Party's official policy of

Nevertheless, the Commission had firmly rejected the principles on which the National Party's official policy of

Fagan's most significant judgments were about private law, raising little political intrigue: he established that gambling debts are unenforceable in

Fagan's most significant judgments were about private law, raising little political intrigue: he established that gambling debts are unenforceable in

The Chief Justiceship fell vacant upon the retirement at the end of 1956 of

The Chief Justiceship fell vacant upon the retirement at the end of 1956 of  In the end, after discussions with Schreiner, Fagan accepted the post. They decided it was best for him to accept the appointment, despite all its problems, to prevent notorious National Party favourite L. C. Steyn becoming Chief Justice. Initially they had, at Centlivres' suggestion, tried to reach an agreement among the judges of the Court that they would all refuse appointment, so that the government would be forced to appoint Schreiner. But this plan failed, unsurprisingly, when Steyn refused to agree. Fagan therefore accepted the Chief Justiceship with misgivings. He wrote to his wife after his appointment that he still felt "sick about Oliver chreiner and ashamed when people congratulated him.

In the end, after discussions with Schreiner, Fagan accepted the post. They decided it was best for him to accept the appointment, despite all its problems, to prevent notorious National Party favourite L. C. Steyn becoming Chief Justice. Initially they had, at Centlivres' suggestion, tried to reach an agreement among the judges of the Court that they would all refuse appointment, so that the government would be forced to appoint Schreiner. But this plan failed, unsurprisingly, when Steyn refused to agree. Fagan therefore accepted the Chief Justiceship with misgivings. He wrote to his wife after his appointment that he still felt "sick about Oliver chreiner and ashamed when people congratulated him.

Chief Justice of South Africa

The Chief Justice of South Africa is the most senior judge of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, Constitutional Court and head of the judiciary of South Africa, who exercises final authority over the functioning and management of all the c ...

from 1957 to 1959 and previously a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

and the Minister of Native Affairs

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

in J. B. M. Hertzog

General James Barry Munnik Hertzog (3 April 1866 – 21 November 1942), better known as Barry Hertzog or J. B. M. Hertzog, was a South African politician and soldier. He was a Boer general during the Second Boer War who served ...

's government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

. Fagan had been an early supporter of the Afrikaans language movement The Afrikaans language movement is one of three efforts that have been organised to promote Afrikaans in South Africa.Hein Willemse"More than an oppressor’s language: reclaiming the hidden history of Afrikaans" ''theconversation.com'', April 27, 2 ...

and a noted Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gra ...

playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

and novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire to ...

. Though he was a significant figure in the rise of Afrikaner nationalism

Afrikaner nationalism ( af, Afrikanernasionalisme) is a nationalistic political ideology which created by Afrikaners residing in Southern Africa during the Victorian era. The ideology was developed in response to the significant events in Afrik ...

and a long-term member of the Broederbond

The Afrikaner Broederbond (AB) or simply the Broederbond was an exclusively Afrikaner Calvinist and male secret society in South Africa dedicated to the advancement of the Afrikaner people. It was founded by H. J. Klopper, H. W. van der Merw ...

, he later became an important opponent of Hendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of ''Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

's National Party and is best known for the report of the Fagan Commission

The Native Laws Commission, commonly known as the Fagan Commission, was appointed by the South African Government in 1946 to investigate changes to the system of segregation. Its members were: Henry Allan Fagan, A. S. Welsh, A. L. Barrett, E. E. v ...

, whose relatively liberal approach to racial integration amounted to the Smuts government's last, doomed stand against the policy of apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

.

Early life and education

Fagan was born inTulbagh

Tulbagh, named after Dutch Cape Colony Governor Ryk Tulbagh, is a town located in the "Land van Waveren" mountain basin (also known as the Tulbagh basin), in the Winelands of the Western Cape, South Africa. The basin is fringed on three sides ...

, a historical town in the winelands of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

, in 1889. He was the oldest of seven children. His father was a lawyer and amateur poet, and kept a vast collection of books at the family's Cape Dutch

Cape Dutch, also commonly known as Cape Afrikaners, were a historic socioeconomic class of Afrikaners who lived in the Western Cape during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The terms have been evoked to describe an affluent, apolitical se ...

residence (now a National Monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure.

The term may also refer to a spec ...

) on Kerk Straat, including leading works of theology and English literature. Fagan began his schooling in Tulbagh but completed the bulk of it in Somerset West

Somerset West ( af, Somerset-Wes) is a town in the Western Cape, South Africa. Organisationally and administratively it is included in the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality as a suburb of the Helderberg region (formerly called Hottent ...

. In 1905 he went to Victoria College (later to become the University of Stellenbosch), from which he earned a BA in Literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

. He hoped (like many of his peers) to be a minister of religion

In Christianity, a minister is a person authorised by a church or other religious organization to perform functions such as teaching of beliefs; leading services such as weddings, baptisms or funerals; or otherwise providing spiritual guidanc ...

, and went to the seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

in Stellenbosch

Stellenbosch (; )A Universal Pronounc ...

; but his father's long-standing wish was that he would become a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

, and continued to pay for private lessons in law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

.

In the end, Fagan opted for law, and was admitted to the LLB

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the China, People's Republic ...

program at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

in 1911. There he lived with his maternal uncle, J. J. Smith, who was researching Afrikaans in the library of the Museum of London

The Museum of London is a museum in London, covering the history of the UK's capital city from prehistoric to modern times. It was formed in 1976 by amalgamating collections previously held by the City Corporation at the Guildhall, London, Gui ...

and would later become the leading figure in the Afrikaans language movement The Afrikaans language movement is one of three efforts that have been organised to promote Afrikaans in South Africa.Hein Willemse"More than an oppressor’s language: reclaiming the hidden history of Afrikaans" ''theconversation.com'', April 27, 2 ...

and compiler of the language's first standard dictionary. Smith soon persuaded Fagan of the cultural importance of Afrikaans — Fagan had believed hitherto that a simplified form of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

was the best way to develop a written language for the Afrikaner people

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from Free Burghers, predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: ...

— and encouraged him to write his first Afrikaans poetry and short stories. Fagan earned his LLB

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the China, People's Republic ...

in 1914, and was admitted to the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wal ...

the following year. He then returned to South Africa to practice at the Cape Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

.

Political career

Early involvement in the Afrikaner language movement

Fagan returned to the Cape at a time of great turbulence and excitement. The Afrikaans language movement was taking shape andJ. B. M. Hertzog

General James Barry Munnik Hertzog (3 April 1866 – 21 November 1942), better known as Barry Hertzog or J. B. M. Hertzog, was a South African politician and soldier. He was a Boer general during the Second Boer War who served ...

would soon found his National Party, and Fagan was thrust into this emerging movement for Afrikaner nationalism

Afrikaner nationalism ( af, Afrikanernasionalisme) is a nationalistic political ideology which created by Afrikaners residing in Southern Africa during the Victorian era. The ideology was developed in response to the significant events in Afrik ...

. He was the secretary of the committee which founded the Nasionale Pers, becoming a director of the Pers and the assistant editor of its flagship newspaper, ''Die Burger

''Die Burger'' (English: The Citizen) is a daily Afrikaans-language newspaper, published by Naspers. By 2008, it had a circulation of 91,665 in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces of South Africa. Along with ''Beeld'' and ''Volksblad'', it is ...

'', under D. F. Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforc ...

, then beginning his political career as leader of the National Party in the Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

. He also lent editorial supervision to the Pers's family magazine ''Die Huisgenoot

''Huisgenoot'' (Afrikaans for ''House Companion'') is a weekly South African Afrikaans-language general-interest family magazine. It has the highest circulation figures of any South African magazine and is followed by sister magazine ''YOU'', i ...

'', of which his uncle J. J. Smith was the first editor, and translated the works of Theodor Storm

Hans Theodor Woldsen Storm (; 14 September 18174 July 1888), commonly known as Theodor Storm, was a German writer. He is considered to be one of the most important figures of German realism.

Life

Storm was born in the small town of Husum, on th ...

into Afrikaans.

In 1919, Fagan left ''Die Burger'' and became, for a brief period, the first

In 1919, Fagan left ''Die Burger'' and became, for a brief period, the first Professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who pr ...

of Roman-Dutch law

Roman-Dutch law (Dutch: ''Rooms-Hollands recht'', Afrikaans: ''Romeins-Hollandse reg'') is an uncodified, scholarship-driven, and judge-made legal system based on Roman law as applied in the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries. As such, it ...

in the newly formed law faculty at the University of Stellenbosch

Stellenbosch University ( af, Universiteit Stellenbosch) is a public research university situated in Stellenbosch, a town in the Western Cape province of South Africa. Stellenbosch is the oldest university in South Africa and the oldest extant ...

. The following year he returned to legal practice. He continued to be involved in the Afrikaner language movement, and helped ensure, along with his close friend C. J. Langenhoven

Cornelis Jacobus Langenhoven (13 August 1873 – 15 July 1932), who published under his initials C.J. Langenhoven, was a South African poet who played a major role in the development of Afrikaans literature and cultural history. His poetry was ...

, that Afrikaans was made an official language (replacing Dutch) in 1925.

In Parliament

Though Fagan's practice had become very reputable, and he had been appointed aKing's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel ( post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister or ...

in 1927, he was "bitten by the political bug" after Hertzog's National Party achieved electoral success. He decided to stand for election to the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies as the colony gained more internal responsible governme ...

, the lower house of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, in 1929 in the Hottentots-Holland (now Helderberg

Helderberg refers to a planning district of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality, the mountain after which it is named, a wine-producing area in the Western Cape province of South Africa, or a small census area in Somerset West.

Or ...

) district, but lost narrowly. He succeeded four years later, becoming a National Party MP representing Swellendam

Swellendam is the fifth oldest town in South Africa (after Cape Town, Stellenbosch, Simon's Town, and Paarl), a town with 17,537 inhabitants situated in the Western Cape province. The town has over 50 provincial heritage sites, most of them b ...

. When Hertzog fused with Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

' South African Party

nl, Zuidafrikaanse Partij

, leader1_title = Leader (s)

, leader1_name = Louis Botha,Jan Smuts, Barry Hertzog

, foundation =

, dissolution =

, merger = Het VolkSouth African PartyAfrikaner BondOrangia Unie

, merged ...

in 1934, leading to rancor with Malan's now 'purified' National Party

The Purified National Party ( af, Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party) was a break away from Hertzog's National Party (South Africa), National Party which lasted from 1935 to 1948

In 1935 the main portion of the National Party, led by J. B. M. Hertzog, m ...

, Fagan decided — after a two-year delay, during which he occupied his parliamentary seat as a so-called independent Nationalist — to break with Malan and his other old friends and follow Hertzog into the United Party, whose relatively conciliatory racial politics he preferred. In 1936, he was instrumental in setting up the Cape Town-based newspaper ''Die Suiderstem'', an Afrikaans-language mouthpiece for Hertzog (who had lost ''Die Burger''Minister of Native Affairs

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

in Hertzog's government (alongside the likes of Jan Kemp Jan Kemp may refer to:

*Jan Kemp (general) (1872–1946), South African Boer officer, rebel general, and politician

*Jan Kemp (writer)

Janet Mary Riemenschneider-Kemp (born 12 March 1949) is a New Zealand poet, short story writer and public p ...

and Oswald Pirow

Oswald Pirow, QC (Aberdeen, Cape Colony (now Eastern Cape South Africa), 14 August 1890 – Pretoria, Transvaal, Union of South Africa , 11 October 1959) was a South African lawyer and far right politician, who held office as minister of Just ...

) after the 1938 general election and was, in the view of one leading historian, the "most outstanding" of Hertzog's associates. Just a year later, however, Hertzog left the United Party in protest at Smuts' decision, in the face of clamant calls for neutrality from Afrikaans-speakers, to take the country into War

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

in support of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, and Fagan "felt bound to go with him into the political wilderness". Fagan resumed legal practice, but remained an MP. Both he and Hertzog rejoined the National Party a few months later, a move Fagan strongly supported. When Hertzog once again split from Malan in 1941 to form the Afrikaner Party

The Afrikaner Party (AP) was a South African political party from 1941 to 1951.

Origins

The Afrikaner Party's roots can be traced back to September 1939, when South Africa declared war on Germany shortly after the start of World War II. The then ...

, however, Fagan did not follow him, staying instead in the NP caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to a meeting ...

.

Thus, although Fagan had been in the vanguard of the Afrikaner nationalist movement and began and ended his political career as a colleague of Malan's, he "was not a Malanite" and differed in crucial respects, and at crucial historical moments, from the post-Hertzog National Party. The best-known instance would be his report for the Native Laws Commission (commonly called the Fagan Commission), which recommended a gradual liberalisation of South Africa's system of

Thus, although Fagan had been in the vanguard of the Afrikaner nationalist movement and began and ended his political career as a colleague of Malan's, he "was not a Malanite" and differed in crucial respects, and at crucial historical moments, from the post-Hertzog National Party. The best-known instance would be his report for the Native Laws Commission (commonly called the Fagan Commission), which recommended a gradual liberalisation of South Africa's system of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and was accordingly "savaged" by his old party. Fagan was described, at least in these early years, as a "moderate", and retained significant ties to the Afrikaner establishment.

Judicial career

Fagan was made a judge of theCape Provincial Division

The Western Cape Division of the High Court of South Africa (previously named the Cape Provincial Division and the Western Cape High Court, and commonly known as the Cape High Court) is a superior court of law with general jurisdiction over th ...

by Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Smuts in March 1943. It was Smuts who had, as Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a v ...

under Hertzog, offered Fagan the same post some years earlier. Fagan also had eight months' experience as an acting judge in the Kimberley High Court before entering politics. One contemporary observer wrote that Fagan's appointment to the bench was "richly deserved" and met with "universal approbation" from the legal profession. Despite Fagan's association with the ruling United Party, concerns about political interference in judicial appointments were in Fagan's case relatively attenuated.

Unsurprisingly given his previous professorial appointment, Fagan was a "great exponent of Roman-Dutch law

Roman-Dutch law (Dutch: ''Rooms-Hollands recht'', Afrikaans: ''Romeins-Hollandse reg'') is an uncodified, scholarship-driven, and judge-made legal system based on Roman law as applied in the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries. As such, it ...

", and his best-known judgments were those which dealt closely with the old authorities like Voet and the '' Digest''. Yet, unlike many other judges with Afrikaner nationalist leanings, Fagan did not shun English law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

on principle.

Fagan Commission

In 1946, as pressure was building from Malan's reactionary National Party, Smuts sought to devise a comprehensive United Party position on the so-called native question. For this purpose he appointed the independent Native Laws Commission, with Fagan as its head, to investigate changes to the system of segregation. When the Commission reported in 1948, it stated that the total segregation or apartheid envisaged by the National Party was "utterly impracticable", since South Africa's racial groups were inevitably interdependent, and the 'reserves' set aside for black South Africans were far too small to support them. It therefore recommended that 'influx control' measures be relaxed, allowing black South Africans to move to cities with relative freedom and the incremental integration of the races. Yet the report did not favour racial equality, and rejected the full social or political integration of black people as unacceptable. It recommended liberalisation primarily on the basis that it would benefit the white population economically, and recommended accordingly that only those black persons who would benefit industry should be allowed to stay in the cities. Nevertheless, the Commission had firmly rejected the principles on which the National Party's official policy of

Nevertheless, the Commission had firmly rejected the principles on which the National Party's official policy of apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

was based, and therefore raised its ire. Hendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of ''Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

, then an MP and the editor of ''Die Transvaler

''Die Transvaler'' was a South African newspaper founded in 1937 with the aim of promoting Afrikaner nationalism and supporting the Transvaal branch of the National Party. Hendrik Verwoerd was its first editor.

In 1937, ''Nasionale Pers'' set ...

'', was especially critical. And a declaration signed by a prominent group of Stellenbosch academics angrily pointed out that if Fagan's racial integration were allowed this would lead inevitably to ''gelykstelling'' (social levelling) and, as a result of pressure to give blacks equal civil rights, the political marginalisation of the white population; the upshot would be the death of the Afrikaner ''volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term ''folk'') ...

''. Though they were angry, the Nationalists had not been caught unprepared: in fact, Malan had already set up a rival commission headed by his closest confidante, Paul Sauer, and staffed by three NP parliamentarians, and which had reported in 1947. The Sauer Commission

The Sauer Commission (South Africa), was created in 1948 largely in response to the Fagan Commission. It was appointed by the Herenigde Nasionale Party and favoured even stricter segregation laws.

The Sauer Commission was concerned with the 'pro ...

had given added detail and heft to the Nationalists' policy of apartheid, recommending that influx control measures be strengthened to prevent any mixing between the races, with black people consigned to the reserves. It was this hard-line view which triumphed when Malan's National Party won the 1948 general election.

Appellate Division

Despite the uncongenial report of his Commission, the Malan government was willing to elevate Fagan to the Appellate Division, the country's highest court, in October 1950, to replace the departed Chief Justice Watermeyer. Concern was growing at that stage that the Nationalists were trying to fill the Appellate Division with loyalists, but in Fagan's case these concerns were, again, attenuated; despite his links with the government, he was a moderate whose appointment was justified on merit.South African law

South Africa has a 'hybrid' or 'mixed' legal system, formed by the interweaving of a number of distinct legal traditions: a civil law system inherited from the Dutch, a common law system inherited from the British, and a customary law syste ...

, and that undue influence

Undue influence (UI) is a psychological process by which a person's free will and judgement is supplanted by that of another. It is a legal term and the strict definition varies by jurisdiction. Generally speaking, it is a means by which a pers ...

vitiates a contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to tran ...

. But he did find against the government in its attempt to enforce the Population Registration Act, 1950

The Population Registration Act of 1950 required that each inhabitant of South Africa be classified and registered in accordance with their racial characteristics as part of the system of apartheid.

Social rights, political rights, educational ...

, raising the standard of proof required to classify a person as 'non-European' on the provocative basis that Parliament could not have intended something so unjust as foisting that status on a person without adequate proof.

Chief Justice

Greater political intrigue marked his appointment and tenure asChief Justice of South Africa

The Chief Justice of South Africa is the most senior judge of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, Constitutional Court and head of the judiciary of South Africa, who exercises final authority over the functioning and management of all the c ...

.

The Chief Justiceship fell vacant upon the retirement at the end of 1956 of

The Chief Justiceship fell vacant upon the retirement at the end of 1956 of Albert van der Sandt Centlivres

Albert van der Sandt Centlivres (13 January 1887 – 19 September 1966), was the Chief Justice of South Africa from 1950 to 1957.

Biography

Centlivres was born in Newlands, Cape Town, the son of Frederick James Centlivres and Albertina de V ...

. Centlivres had stood firm, in the ''Harris v Minister of the Interior'' cases, against the Nationalists' first attempts to strip coloured

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

voters in the Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

of their right to vote, which was constitutionally entrenched in the South Africa Act

The South Africa Act 1909 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which created the Union of South Africa from the British Cape Colony, Colony of Natal, Orange River Colony, and Transvaal Colony. The Act also made provisions for pote ...

. But virtually his last act as a judge was finally to relent, in ''Collins v Minister of the Interior'', and to give legal sanction to the disenfranchisement, which the National Party, now led by J. G. Strydom after Malan's death, had secured by packing the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. Fagan, too, had sat in this last case (but not in ''Harris''), and concurred in Centlivres' judgment. The lone dissentient was Oliver Schreiner

Oliver Deneys Schreiner Military Cross, MC King's Counsel, KC (29 December 1890 – 27 July 1980), was a judge of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of South Africa. One of the most renowned South African judges, he was passed over twice ...

, a noted liberal judge of very high esteem. Schreiner was also the most senior judge on the Appellate Division after Centlivres' retirement, and was therefore first in line, according to long-standing convention, for appointment as Chief Justice. Yet he had plainly proven himself to be politically unsafe during this so-called coloured vote crisis, and was, presumably as a result, passed over by the Nationalist government. This move was widely condemned. The next most senior judge, Hoexter, had joined Centlivres' judgment in ''Collins'', but had voted against the government in the ''Harris'' cases, so he, too, was disfavoured. That left Fagan, untainted by any association with ''Harris'' and with clear Afrikaner and Nationalist ties, who was offered the post by Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a v ...

C. R. Swart

Charles Robberts Swart (5 December 1894 – 16 July 1982), nicknamed ''Blackie'', was a South African politician who served as the last governor-general of the Union of South Africa from 1959 to 1961 and the first state president of the Repub ...

. Fagan was shocked by the offer, describing it as a "bolt from the blue". In a letter to Swart, Fagan said he was faced with "a very difficult choice", noting his concerns about superseding the more senior Schreiner and the obvious implication that the offer was politically motivated.

In the end, after discussions with Schreiner, Fagan accepted the post. They decided it was best for him to accept the appointment, despite all its problems, to prevent notorious National Party favourite L. C. Steyn becoming Chief Justice. Initially they had, at Centlivres' suggestion, tried to reach an agreement among the judges of the Court that they would all refuse appointment, so that the government would be forced to appoint Schreiner. But this plan failed, unsurprisingly, when Steyn refused to agree. Fagan therefore accepted the Chief Justiceship with misgivings. He wrote to his wife after his appointment that he still felt "sick about Oliver chreiner and ashamed when people congratulated him.

In the end, after discussions with Schreiner, Fagan accepted the post. They decided it was best for him to accept the appointment, despite all its problems, to prevent notorious National Party favourite L. C. Steyn becoming Chief Justice. Initially they had, at Centlivres' suggestion, tried to reach an agreement among the judges of the Court that they would all refuse appointment, so that the government would be forced to appoint Schreiner. But this plan failed, unsurprisingly, when Steyn refused to agree. Fagan therefore accepted the Chief Justiceship with misgivings. He wrote to his wife after his appointment that he still felt "sick about Oliver chreiner and ashamed when people congratulated him.

Retirement

When Fagan's judicial career ended in 1959, he re-entered politics, and became a strong opponent of the National Party's increasingly conservative policies underHendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of ''Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

. His remarks on the government's racial policy, serialized in the largest Afrikaans newspaper, '' Die Landstem'', were hailed for "breaking the facade of Nationalist unity" and finally sparking an effective opposition to apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

from within the establishment. Though there had been many black opponents of the government, as well as some prominent critics among white English-speakers, Fagan was one of the first Afrikaners to break ranks. His views had added traction among ordinary Afrikaners as a result of his being a celebrated Afrikaner author.

Fagan's monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monograph ...

, ''Our Responsibility'', published in February 1960, said (echoing the words of the Fagan Commission) that Verwoerd's policies were "hopelessly impractical", and that South Africa's white population had to accept racial integration. The book was given a scathing review by Piet Cillié, then editor of ''Die Burger

''Die Burger'' (English: The Citizen) is a daily Afrikaans-language newspaper, published by Naspers. By 2008, it had a circulation of 91,665 in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces of South Africa. Along with ''Beeld'' and ''Volksblad'', it is ...

'' and a staunch Nationalist.

Fagan's public pronouncements resulted in calls for him to lead a political movement. He agreed to become the leader of the National Union (NU), a party newly founded by Japie Basson, a firebrand MP who had been recently expelled from the National Party for criticising Verwoerd. The party was intended to provide a home for Nationalist supporters who refused to tolerate Strydom's disregard for constitutional principles (particularly during the coloured vote crisis, as Fagan well knew). Fagan stood for election as South Africa's first State President

The State President of the Republic of South Africa ( af, Staatspresident) was the head of state of South Africa from 1961 to 1994. The office was established when the country became a republic on 31 May 1961, albeit, outside the Commonweal ...

after whites voted in a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

in 1960 to establish a republic, but was defeated by former NP minister and the last Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

C. R. Swart

Charles Robberts Swart (5 December 1894 – 16 July 1982), nicknamed ''Blackie'', was a South African politician who served as the last governor-general of the Union of South Africa from 1959 to 1961 and the first state president of the Repub ...

by 139 votes to 71. However, he became a senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

for the NU, and also its leader. The NU contested the 1961 election in alliance with the United Party, now led by Sir De Villiers Graaff

Sir De Villiers Graaff, 2nd Baronet, (8 December 1913 – 4 October 1999) (first name De Villiers, surname Graaff) known as Div Graaff, was a South African politician who succeeded his father, Sir David Pieter de Villiers Graaff, 1st Baronet, ...

.

The NU soon fizzled out, and Fagan spent his final years as a Senator for the United Party, continuing to argue publicly for racial conciliation, now in the ''Johannesburg Star

''The Star'' is a daily newspaper based in Gauteng, South Africa. The paper is distributed mainly in Gauteng and other provinces such as Mpumalanga, Limpopo, North West, and Free State.

''The Star'' is one of the titles of the South African I ...

''. His second treatise on racial politics, ''Co-existence'', was published shortly before his death in 1963.

Legacy

One prominent journalist wrote in 1998, in light of theFagan Commission

The Native Laws Commission, commonly known as the Fagan Commission, was appointed by the South African Government in 1946 to investigate changes to the system of segregation. Its members were: Henry Allan Fagan, A. S. Welsh, A. L. Barrett, E. E. v ...

's liberal report, which might have changed South African history had the Nats not suppressed it, that Fagan was one of the "unsung heroes" of Afrikaner history. According to ''Die Burger'', however, the report, by documenting the extent to which the races had become integrated, had only helped show how imperative it was to forcibly separate them. That assessment was self-serving, but undoubtedly Fagan's views were more conservative than other critics of the government, like Alan Paton

Alan Stewart Paton (11 January 1903 – 12 April 1988) was a South African writer and anti-apartheid activist. His works include the novels ''Cry, the Beloved Country'' and '' Too Late the Phalarope''.

Family

Paton was born in Pietermaritzbu ...

's Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, and did not question the fact that South Africa's white population ought to be preserved and indeed preferred. Throughout his time as an MP, his views were sufficiently close to Malan's that he could move seamlessly in and out of the National Party, with which he keenly reunified in 1940. Even after the antipathy sparked by the Fagan Commission, and his retirement from the judiciary, his recommendations on the racial question were, in essence, to re-institute Hertzog's racial policies. Yet in part it was precisely because he was no more than a "moderate", who retained significant ties to the Afrikaner establishment, and whose criticisms were so "measured", that his criticisms were able to have an impact.

Family life

Fagan married Jessie "Queeny" Theron, also from Tulbagh, in 1922. She was often the lead actress in performances of Fagan's plays. They had three sons, the last of whom,Johannes

Johannes is a Medieval Latin form of the personal name that usually appears as "John" in English language contexts. It is a variant of the Greek and Classical Latin variants (Ιωάννης, ''Ioannes''), itself derived from the Hebrew name '' Yeh ...

, became a judge of the Cape Provincial Division

The Western Cape Division of the High Court of South Africa (previously named the Cape Provincial Division and the Western Cape High Court, and commonly known as the Cape High Court) is a superior court of law with general jurisdiction over th ...

in 1977. The family lived in Bishopscourt, Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, where Fagan died of a heart attack on 6 December 1963.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fagan, Henry Allan 1889 births 1963 deaths Stellenbosch University alumni Alumni of the University of London Chief justices of South Africa People from Tulbagh South African people of British descent South African people of Irish descent South African Queen's Counsel White South African people South African judges