Hemagglutinin (influenza) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Influenza hemagglutinin (HA) or haemagglutinin /sup> (

A highly pathogenic avian flu virus of H5N1 type has been found to infect humans at a low rate. It has been reported that single

A highly pathogenic avian flu virus of H5N1 type has been found to infect humans at a low rate. It has been reported that single

Jmol tutorial of influenza hemagglutinin structure and activity.

* (April 2006)

Influenza Research Database

Database of influenza protein sequences and structures

3D macromolecular structures of influenza hemagglutinin from the EM Data Bank(EMDB)

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hemagglutinin (Influenza) Influenza A virus Viral structural proteins

British English

British English (BrE, en-GB, or BE) is, according to Lexico, Oxford Dictionaries, "English language, English as used in Great Britain, as distinct from that used elsewhere". More narrowly, it can refer specifically to the English language in ...

) is a homotrimeric glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as g ...

found on the surface of influenza virus

A virus is a wikt:submicroscopic, submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and ...

es and is integral to its infectivity.

Hemagglutinin is a Class I Fusion Protein, having multifunctional activity as both an attachment factor and membrane fusion protein

Membrane fusion proteins (not to be confused with chimeric or fusion proteins) are proteins that cause fusion of biological membranes. Membrane fusion is critical for many biological processes, especially in eukaryotic development and viral entry ...

. Therefore, HA is responsible for binding Influenza virus

A virus is a wikt:submicroscopic, submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and ...

to sialic acid on the surface of target cells, such as cells in the upper respiratory tract or erythrocytes, causing as a result the internalization of the virus. Secondarily, HA is responsible for the fusion of the viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

with the late endosomal membrane once exposed to low pH (5.0-5.5).

The name "hemagglutinin" comes from the protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

's ability to cause red blood cells (erythrocytes) to clump together ("agglutinate

In linguistics, agglutination is a morphological process in which words are formed by stringing together morphemes, each of which corresponds to a single syntactic feature. Languages that use agglutination widely are called agglutinative langu ...

") ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in biology and ...

''.

Subtypes

Hemagglutinin (HA) in influenza A has at least 18 different subtypes. These subtypes are named H1 through H18. H16 was discovered in 2004 on influenza A viruses isolated from black-headedgull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the family Laridae in the suborder Lari. They are most closely related to the terns and skimmers and only distantly related to auks, and even more distantly to waders. Until the 21st century, ...

s from Sweden and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. H17 was discovered in 2012 in fruit bats. Most recently, H18 was discovered in a Peruvian bat in 2013. The first three hemagglutinins, H1, H2, and H3, are found in human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

influenza viruses. By phylogenic similarity, the HA proteins are divided into 2 groups, with H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, H9, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, and H18 belonging to group 1 and the rest in group 2. The serotype of influenza A virus is determined by the Hemagglutinin (HA) and Neuraminidase (NA) proteins present on its surface. Neuraminidase (NA) has 11 known subtypes, hence influenza virus is named as H1N1, H5N2 etc., depending on the combinations of HA and NA.

A highly pathogenic avian flu virus of H5N1 type has been found to infect humans at a low rate. It has been reported that single

A highly pathogenic avian flu virus of H5N1 type has been found to infect humans at a low rate. It has been reported that single amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

changes in this avian virus strain's type H5 hemagglutinin have been found in human patients that "can significantly alter receptor specificity of avian H5N1 viruses, providing them with an ability to bind to receptors optimal for human influenza viruses". This finding seems to explain how an H5N1 virus that normally does not infect humans can mutate and become able to efficiently infect human cells. The hemagglutinin of the H5N1 virus has been associated with the high pathogenicity of this flu virus strain, apparently due to its ease of conversion to an active form by proteolysis.

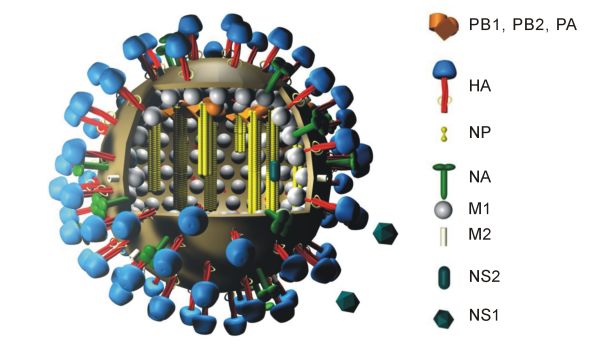

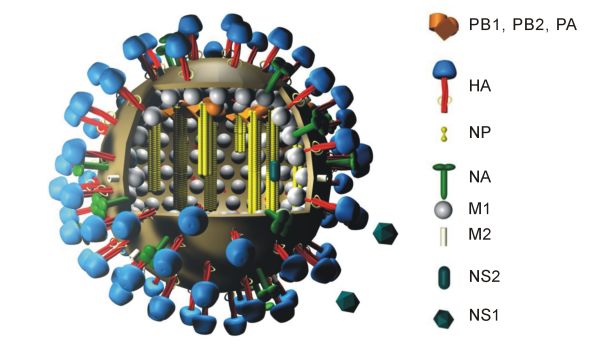

Structure

HA is a homotrimeric integral membraneglycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as g ...

. It is shaped like a cylinder, and is approximately 13.5 nanometres long. HA trimer is made of three identical monomers. Each monomer is made of an intact HA0 single polypeptide chain with HA1 and HA2 regions that are linked by 2 disulfide bridges. Each HA2 region adopts alpha helical coiled coil structure and sits on top of the HA1 region, which is a small globular domain that consists of a mix of α/β structures. The HA trimer is synthesized as inactive precursor protein HA0 to prevent any premature and unwanted fusion activity and must be cleaved by host proteases in order to be infectious. At neutral pH, the 23 residues near the N-terminus

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

of HA2, also known as the fusion peptide that is eventually responsible for fusion between viral and host membrane, is hidden in a hydrophobic pocket between the HA2 trimeric interface. The C-terminus

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein i ...

of HA2, also known as the transmembrane domain, spans the viral membrane and anchors protein to the membrane.

;HA1

: HA1 is mostly composed of antiparallel beta-sheets.

;HA2

:HA2 domain contains three long alpha helices, one from each monomer. Each of these helices is connected by a flexible, loop region called Loop-B (residue 59 to 76).

Function

HA plays two key functions in viral entry. Firstly, it allows the recognition of targetvertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxon, taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with vertebral column, backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the ...

cells, accomplished through the binding to these cells' sialic acid-containing receptors. Secondly, once bound it facilitates the entry of the viral genome into the target cells by causing the fusion of host endosomal membrane with the viral membrane.

Specifically, the HA1 domain of the protein binds to the monosaccharide sialic acid which is present on the surface of its target cells, allowing attachment of viral particle to the host cell surface. HA17 and HA18 have been described to bind MHC class II molecules as a receptor for entry rather than sialic acid. The host cell membrane then engulfs the virus, a process known as endocytosis, and pinches off to form a new membrane-bound compartment within the cell called an endosome. The cell then attempts to begin digesting the contents of the endosome by acidifying its interior and transforming it into a lysosome. Once the pH within the endosome drops to about 5.0 to 6.0, a series of conformational rearrangement occurs to the protein. First, fusion peptide is released from the hydrophobic pocket and HA1 is dissociated from HA2 domain. HA2 domain then undergoes extensive conformation change that eventually bring the two membranes into close contact.

This so-called " fusion peptide" that was released as pH is lowered, acts like a molecular grappling hook by inserting itself into the endosomal membrane and locking on. Then, HA2 refolds into a new structure (which is more stable at the lower pH), it "retracts the grappling hook" and pulls the endosomal membrane right up next to the virus particle's own membrane, causing the two to fuse together. Once this has happened, the contents of the virus such as viral RNA are released in the host cell's cytoplasm and then transported to the host cell nucleus for replication.

As a treatment target

Since hemagglutinin is the major surface protein of the influenza A virus and is essential to the entry process, it is the primary target ofneutralizing antibodies

A neutralizing antibody (NAb) is an antibody that defends a cell from a pathogen or infectious particle by neutralizing any effect it has biologically. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic.

Neutralizing antibo ...

. These antibodies against flu have been found to act by two different mechanisms, mirroring the dual functions of hemagglutinin:

Head antibodies

Some antibodies against hemagglutinin act by inhibiting attachment. This is because these antibodies bind near the top of the hemagglutinin "head" (blue region in figure above) and physically block the interaction with sialic acid receptors on target cells.Stem antibodies

This group of antibodies acts by preventing membrane fusion (only ''in vitro''; the efficacy of these antibodies ''in vivo'' is believed to be a result of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and the complement system). The stem or stalk region of HA (HA2), is highly conserved across different strains of influenza viruses. The conservation makes it an attractive target for broadly neutralizing antibodies that target all flu subtypes, and for developing universal vaccines that let humans produce these antibodies naturally. Its structural changes from prefusion to postfusion conformation drives fusion between viral membrane and host membrane. Therefore, antibodies targeting this region can block key structural changes that eventually drive the membrane fusion process, and therefore are able to achieve antiviral activity against several influenza virus subtypes. At least one fusion-inhibiting antibody was found to bind closer to the top of hemagglutinin, and is thought to work by cross-linking the heads together, the opening of which is thought to be the first step in the membrane fusion process. Examples are human antibodies F10, FI6, CR6261. They recognize sites in the stem/stalk region (orange region in figure at right), far away from the receptor binding site. In 2015 researchers designed an immunogen mimicking the HA stem, specifically the area where the antibody ties to the virus of the antibody CR9114. Rodent and nonhuman primate models given the immunogen produced antibodies that could bind with HAs in many influenza subtypes, including H5N1. When the HA head is present, the immune system does not generally make bNAbs (broadly neutralizing antibodies). Instead, it makes the head antibodies that only recognize a few subtypes. Since the head is responsible for holding the three HA units together, a stem-only HA needs its own way to hold itself together. One team designed self-assembling HA-stem nanoparticles, using a protein called ferritin to hold the HA together. Another replaced and addedamino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s to stabilize a mini-HA lacking a proper head.

A 2016 vaccine trial in humans found many broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting the stem produced by the immune system. Three classes of highly similar antibodies were recovered from multiple human volunteers, suggesting that a universal vaccine that produces reproducible antibodies is indeed possible.

Other agents

There are also other hemagglutinin-targeted influenza virus inhibitors that are not antibodies: #Arbidol

Umifenovir, sold under the brand name Arbidol, is an antiviral medication for the treatment of influenza and COVID infections used in Russia and China. The drug is manufactured by Pharmstandard (russian: Фармстандарт). It is not a ...

# Small Molecules

# Natural compounds

# Proteins and peptides

See also

* FI6 antibody * Phytohemagglutinin * Hemagglutinin * Neuraminidase * Antigenic shift * Sialic acid * Epitope *H5N1 genetic structure

H5N1 genetic structure is the molecular structure of the H5N1 virus's RNA.

H5N1 is an Influenza A virus subtype. Experts believe it might mutate into a form that transmits easily from person to person. If such a mutation occurs, it might rema ...

Notes

: /small> ^Hemagglutinin is pronounced /he-mah-Glue-tin-in/.References

External links

Jmol tutorial of influenza hemagglutinin structure and activity.

* (April 2006)

Influenza Research Database

Database of influenza protein sequences and structures

3D macromolecular structures of influenza hemagglutinin from the EM Data Bank(EMDB)

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hemagglutinin (Influenza) Influenza A virus Viral structural proteins