Hellenistic Astronomy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Greek astronomy is

Greek astronomy is

Although there is no material evidence of much of the work done by Greek philosophers between 600-300 BC, it is believed that Anaximander (c. 610 BC–c. 546 BC) described a cyclical Earth suspended in the center of the cosmos surrounded by rings of fire, and that

Although there is no material evidence of much of the work done by Greek philosophers between 600-300 BC, it is believed that Anaximander (c. 610 BC–c. 546 BC) described a cyclical Earth suspended in the center of the cosmos surrounded by rings of fire, and that

Plato's main books on cosmology are the ''

Plato's main books on cosmology are the ''

In the 3rd century BC, Aristarchus of Samos proposed an alternate

In the 3rd century BC, Aristarchus of Samos proposed an alternate

(

Almagest Planetary Model Animations

{{DEFAULTSORT:Greek Astronomy

Greek astronomy is

Greek astronomy is astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

written in the Greek language

Greek ( el, label= Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy ( Calabria and Salento), southe ...

in classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

, Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, Greco-Roman, and Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

eras. It is not limited geographic

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

ally to Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

or to ethnic Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, as the Greek language had become the language of scholarship throughout the Hellenistic world

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

following the conquests of Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

. This phase of Greek astronomy is also known as Hellenistic astronomy, while the pre-Hellenistic phase is known as Classical Greek astronomy. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, much of the Greek and non-Greek astronomers

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either obse ...

working in the Greek tradition studied at the Museum

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make thes ...

and the Library of Alexandria in Ptolemaic Egypt.

The development of astronomy by the Greek and notably Hellenistic astronomers is considered to be a major phase in the history of astronomy. Greek astronomy is characterized by seeking a geometrical model for celestial phenomena. Most of the names of the stars, planets, and constellations of the northern hemisphere are inherited from the terminology of Greek astronomy, which are however indeed transliterated from the empirical knowledge in Babylonian astronomy

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia.

Babylonian astronomy seemed to have focused on a select group of stars and constellations known as Ziqpu stars. These constellations ...

, characterized by its theoretical model formulation in terms of algebraic and numerical relations, and to a lesser extent from Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

astronomy. Later, the scientific work by astronomers and mathematicians of the arbo-moslem empire, of diverse backgrounds and religions (such as the Syriac Christians), to translate, comment and then correct Ptolemy's Almagest, influenced in their turn Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

and Western European

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

astronomy.

Archaic Greek astronomy

BothHesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet ...

and Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

were directly and deeply influenced by the mythologies of Phoenicia and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, thanks to Phoenician sailors and literate Babylonians

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. 1 ...

and Arameans, who went to Lefkandi in Greece during the Orientalizing Period, between c. 750 BC and c. 630 BC for maritime commerce and to live and work. The Babylonians and Arameans came from the Levant and North Syria where they were forcibly transported in their hundreds of thousands by the Assyrian army from Babylonia during the reign of the last six Assyrian kings, from 745 BC to 627 BC. Hesiod's theogony and cosmogony are the Greek version of two Phoenician myths. The Odyssey of Homer is inspired by the Epopee of Gilgamesh. See for references the work of M.L. West et W. Burkret.

In this context it is reasonable to suggest that whatever Homer and Hesiod hinted at in their small contributions comes from the knowledge they acquired from the Oriental people they rubbed shoulder with in Lefkandi, the center of Greek culture at that time. References to identifiable stars and constellations appear in the writings of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

and Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet ...

, the earliest surviving examples of Greek literature. In the oldest European texts, the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' and the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'', Homer has noted several astronomical phenomena including solar eclipses. In the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' and the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'', Homer refers to the following celestial objects:

* the constellation Boötes

* the star cluster Hyades Hyades may refer to:

* Hyades (band)

*Hyades (mythology)

*Hyades (star cluster)

The Hyades (; Greek Ὑάδες, also known as Caldwell 41, Collinder 50, or Melotte 25) is the nearest open cluster and one of the best-studied star clusters. Loca ...

* the constellation Orion

* the star cluster Pleiades

The Pleiades (), also known as The Seven Sisters, Messier 45 and other names by different cultures, is an asterism and an open star cluster containing middle-aged, hot B-type stars in the north-west of the constellation Taurus. At a distance ...

* Sirius

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. Its name is derived from the Greek word , or , meaning 'glowing' or 'scorching'. The star is designated α Canis Majoris, Latinized to Alpha Canis Majoris, and abbreviated Alpha CM ...

, the Dog Star

* the constellation Ursa Major

Ursa Major (; also known as the Great Bear) is a constellation in the northern sky, whose associated mythology likely dates back into prehistory. Its Latin name means "greater (or larger) bear," referring to and contrasting it with nearby Ursa ...

Although there is no material evidence of much of the work done by Greek philosophers between 600-300 BC, it is believed that Anaximander (c. 610 BC–c. 546 BC) described a cyclical Earth suspended in the center of the cosmos surrounded by rings of fire, and that

Although there is no material evidence of much of the work done by Greek philosophers between 600-300 BC, it is believed that Anaximander (c. 610 BC–c. 546 BC) described a cyclical Earth suspended in the center of the cosmos surrounded by rings of fire, and that Philolaus

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pyt ...

(c. 480 BC–c. 405 BC) the Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

described a cosmos in which the stars and ten bodies including the planets, the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

, the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, and counter-Earth ('' Antichthon'') circle an unseen central fire. It is hence pure conjecture that Greeks of the 6th and 5th centuries BC were aware of the planets and speculated about the structure of the cosmos.

Also, a more detailed description about the cosmos, Stars, Sun, Moon and the Earth can be found in the Orphism, which dates back to the end of the 5th century BC. Within the lyrics of the Orphic poems we can find remarkable information such as that the Earth is round, it has an axis and it moves around it in one day, it has three climate zones and that the Sun magnetizes the Stars and planets.

The Planets in Early Greek Astronomy

The term "planet" comes from the Greek term πλανήτης (''planētēs''), meaning "wanderer", as ancient astronomers noted how certain points of lights moved across the sky in relation to the other stars. Five extraterrestrial planets can be seen with the naked eye: Mercury,Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

, and Saturn, the Greek names being Hermes, Aphrodite, Ares, Zeus and Cronus. Sometimes the luminaries, the Sun and Moon, are added to the list of naked eye planets to make a total of seven. Since the planets disappear from time to time when they approach the Sun, careful attention is required to identify all five. Observations of Venus are not straightforward. Early Greek astronomers thought that the evening and morning appearances of Venus represented two different objects, calling it ''Hesperus

In Greek mythology, Hesperus (; grc, Ἕσπερος, Hésperos) is the Evening Star, the planet Venus in the evening. He is one of the '' Astra Planeta''. A son of the dawn goddess Eos ( Roman Aurora), he is the half-brother of her other son, ...

'' ("evening star") when it appeared in the western evening sky and ''Phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

'' ("light-bringer") when it appeared in the eastern morning sky. They eventually came to recognize that both objects were the same planet. Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politi ...

is given credit for this realization.

Eudoxan astronomy

In classical Greece, astronomy was a branch of mathematics; astronomers sought to create geometrical models that could imitate the appearances of celestial motions. This tradition began with thePythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

, who placed astronomy among the four mathematical arts (along with arithmetic, geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ...

, and music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

). The study of number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The original examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers c ...

comprising the four arts was later called the ''Quadrivium

From the time of Plato through the Middle Ages, the ''quadrivium'' (plural: quadrivia) was a grouping of four subjects or arts—arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—that formed a second curricular stage following preparatory work in the ...

''.

Although he was not a creative mathematician, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

(427–347 BC) included the ''quadrivium'' as the basis for philosophical education in the ''Republic''. He encouraged a younger mathematician, Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 410 BC–c. 347 BC), to develop a system of Greek astronomy. According to a modern historian of science, David Lindberg:

The two-sphere model is a geocentric model that divides the cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

into two regions, a spherical Earth, central and motionless (the sublunary sphere In Aristotelian physics and Greek astronomy, the sublunary sphere is the region of the geocentric cosmos below the Moon, consisting of the four classical elements: earth, water, air, and fire.

The sublunary sphere was the realm of changing nature. ...

) and a spherical heavenly realm centered on the Earth, which may contain multiple rotating spheres made of aether.

Plato's main books on cosmology are the ''

Plato's main books on cosmology are the ''Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

*Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Greek ...

'' and the '' Republic''. In them he described the two-sphere model and said there were eight circles or spheres carrying the seven planets and the fixed stars.

According to the "Myth of Er

The Myth of Er is a legend that concludes Plato's ''Republic'' (10.614–10.621). The story includes an account of the cosmos and the afterlife that greatly influenced religious, philosophical, and scientific thought for many centuries.

The story ...

" in the ''Republic'', the cosmos is the Spindle of Necessity

The Myth of Er is a legend that concludes Plato's ''Republic'' (10.614–10.621). The story includes an account of the cosmos and the afterlife that greatly influenced religious, philosophical, and scientific thought for many centuries.

The story ...

, attended by Siren

Siren or sirens may refer to:

Common meanings

* Siren (alarm), a loud acoustic alarm used to alert people to emergencies

* Siren (mythology), an enchanting but dangerous monster in Greek mythology

Places

* Siren (town), Wisconsin

* Siren, Wisc ...

s and spun by the three daughters of the Goddess Necessity known collectively as the Moirai

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Moirai (, also spelled Moirae or Mœræ; grc, Μοῖραι, "lots, destinies, apportioners"), often known in English as the Fates ( la, Fata, Fata, -orum (n)=), were the personifications of fat ...

or Fates.

According to a story reported by Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia (; el, Σιμπλίκιος ὁ Κίλιξ; c. 490 – c. 560 AD) was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian i ...

(6th century), Plato posed a question for the Greek mathematicians of his day: "By the assumption of what uniform and orderly motions can the apparent motions of the planets be accounted for?" (quoted in Lloyd 1970, p. 84). Plato proposed that the seemingly chaotic wandering motions of the planets could be explained by combinations of uniform circular motions centered on a spherical Earth, a novel idea in the 4th century.

Eudoxus rose to the challenge by assigning to each planet a set of concentric spheres. By tilting the axes of the spheres, and by assigning each a different period of revolution, he was able to approximate the celestial "appearances." Thus, he was the first to attempt a mathematical description of the motions of the planets. A general idea of the content of ''On Speeds'', his book on the planets, can be gleaned from Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

's ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

'' XII, 8, and a commentary by Simplicius on ''De caelo'', another work by Aristotle. Since all his own works are lost, our knowledge of Eudoxus is obtained from secondary sources. Aratus

Aratus (; grc-gre, Ἄρατος ὁ Σολεύς; c. 315 BC/310 BC240) was a Greek didactic poet. His major extant work is his hexameter poem ''Phenomena'' ( grc-gre, Φαινόμενα, ''Phainómena'', "Appearances"; la, Phaenomena), the ...

's poem on astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

is based on a work of Eudoxus, and possibly also Theodosius of Bithynia's ''Sphaerics

''Sphaerics'' ( grc, Σφαιρικά) was a set of three volumes on spherical geometry written by Theodosius of Bithynia in the 2nd century BC. These proved essential in the restoration of Euclidean geometry to Western civilization, when brought ...

''. They give us an indication of his work in spherical astronomy

Spherical astronomy, or positional astronomy, is a branch of observational astronomy used to locate astronomical objects on the celestial sphere, as seen at a particular date, time, and location on Earth. It relies on the mathematical methods o ...

as well as planetary motions.

Callippus

Callippus (; grc, Κάλλιππος; c. 370 BC – c. 300 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician.

Biography

Callippus was born at Cyzicus, and studied under Eudoxus of Cnidus at the Academy of Plato. He also worked with Aristotle at th ...

, a Greek astronomer of the 4th century, added seven spheres to Eudoxus' original 27 (in addition to the planetary spheres, Eudoxus included a sphere for the fixed stars). Aristotle described both systems, but insisted on adding "unrolling" spheres between each set of spheres to cancel the motions of the outer set. Aristotle was concerned about the physical nature of the system; without unrollers, the outer motions would be transferred to the inner planets.

Hellenistic astronomy

Planetary models and observational astronomy

The Eudoxan system had several critical flaws. One was its inability to predict motions exactly. Callippus' work may have been an attempt to correct this flaw. A related problem is the inability of his models to explain why planets appear to change speed. A third flaw is its inability to explain changes in the brightness of planets as seen from Earth. Because the spheres are concentric, planets will always remain at the same distance from Earth. This problem was pointed out in Antiquity byAutolycus of Pitane

Autolycus of Pitane ( el, Αὐτόλυκος ὁ Πιταναῖος; c. 360 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek astronomer, mathematician, and geographer. The lunar crater Autolycus was named in his honour.

Life and work

Autolycus was born in Pitane, ...

(c. 310 BC).

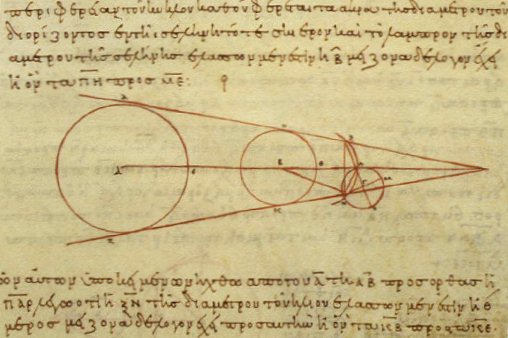

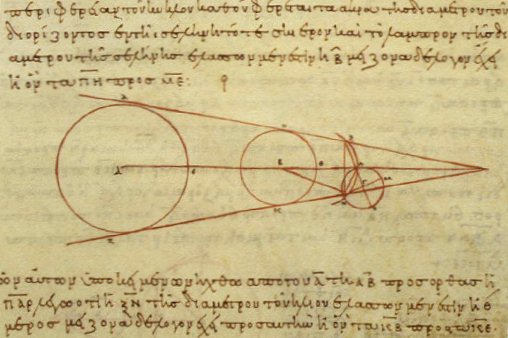

Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 BC–c. 190 BC) responded by introducing two new mechanisms that allowed a planet to vary its distance and speed: the eccentric

Eccentricity or eccentric may refer to:

* Eccentricity (behavior), odd behavior on the part of a person, as opposed to being "normal"

Mathematics, science and technology Mathematics

* Off-center, in geometry

* Eccentricity (graph theory) of a v ...

deferent and the deferent and epicycle

In the Hipparchian, Ptolemaic, and Copernican systems of astronomy, the epicycle (, meaning "circle moving on another circle") was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, S ...

. The deferent is a circle carrying the planet around the Earth. (The word ''deferent'' comes from the Greek fero φέρω "to carry"and Latin ''ferro, ferre'', meaning "to carry.") An eccentric deferent is slightly off-center from Earth. In a deferent and epicycle model, the deferent carries a small circle, the epicycle, which carries the planet. The deferent-and-epicycle model can mimic the eccentric model, as shown by Apollonius' theorem. It can also explain retrogradation

Retrogradation is the landward change in position of the front of a river delta with time. This occurs when the mass balance of sediment into the delta is such that the volume of incoming sediment is less than the volume of the delta that is lost ...

, which happens when planets appear to reverse their motion through the zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The pat ...

for a short time. Modern historians of astronomy have determined that Eudoxus' models could only have approximated retrogradation crudely for some planets, and not at all for others.

In the 2nd century BC, Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

, aware of the extraordinary accuracy with which Babylonian astronomers

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia.

Babylonian astronomy seemed to have focused on a select group of stars and constellations known as Ziqpu stars. These constellations m ...

could predict the planets' motions, insisted that Greek astronomers achieve similar levels of accuracy. Somehow he had access to Babylonian observations or predictions, and used them to create better geometrical models. For the Sun, he used a simple eccentric model, based on observations of the equinoxes

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun crosses the Earth's equator, which is to say, appears directly above the equator, rather than north or south of the equator. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise "due east" and set ...

, which explained both changes in the speed of the Sun and differences in the lengths of the seasons

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperate and po ...

. For the Moon, he used a deferent and epicycle

In the Hipparchian, Ptolemaic, and Copernican systems of astronomy, the epicycle (, meaning "circle moving on another circle") was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, S ...

model. He could not create accurate models for the remaining planets, and criticized other Greek astronomers for creating inaccurate models.

Hipparchus also compiled a star catalogue. According to Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

, he observed a '' nova'' (new star). So that later generations could tell whether other stars came to be, perished, moved, or changed in brightness, he recorded the position and brightness of the stars. Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

mentioned the catalogue in connection with Hipparchus' discovery of precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In oth ...

. (Precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In oth ...

of the equinoxes is a slow motion of the place of the equinoxes through the zodiac, caused by the shifting of the Earth's axis). Hipparchus thought it was caused by the motion of the sphere of fixed stars.

Heliocentrism and cosmic scales

In the 3rd century BC, Aristarchus of Samos proposed an alternate

In the 3rd century BC, Aristarchus of Samos proposed an alternate cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

(arrangement of the universe): a heliocentric model of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

, placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the known universe (hence he is sometimes known as the "Greek Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

"). His astronomical ideas were not well-received, however, and only a few brief references to them are preserved. We know the name of one follower of Aristarchus: Seleucus of Seleucia

Seleucus of Seleucia ( el, Σέλευκος ''Seleukos''; born c. 190 BC; fl. c. 150 BC) was a Hellenistic astronomer and philosopher. Coming from Seleucia on the Tigris, Mesopotamia, the capital of the Seleucid Empire, or, alternatively, Seleuk ...

.

Aristarchus also wrote a book '' On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon'', which is his only work to have survived. In this work, he calculated the sizes of the Sun and Moon, as well as their distances from the Earth in Earth radii

Earth radius (denoted as ''R''🜨 or R_E) is the distance from the center of Earth to a point on or near its surface. Approximating the figure of Earth by an Earth spheroid, the radius ranges from a maximum of nearly (equatorial radius, deno ...

. Shortly afterwards, Eratosthenes calculated the size of the Earth, providing a value for the Earth radii which could be plugged into Aristarchus' calculations. Hipparchus wrote another book '' On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon'', which has not survived. Both Aristarchus and Hipparchus drastically underestimated the distance of the Sun from the Earth.

Astronomy in the Greco-Roman and Late Antique eras

Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

is considered to have been among the most important Greek astronomers, because he introduced the concept of exact prediction into astronomy. He was also the last innovative astronomer before Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

, a mathematician who worked at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

in Roman Egypt in the 2nd century. Ptolemy's works on astronomy and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

include the '' Almagest'', the ''Planetary Hypotheses'', and the ''Tetrabiblos

''Tetrabiblos'' () 'four books', also known in Greek as ''Apotelesmatiká'' () "Effects", and in Latin as ''Quadripartitum'' "Four Parts", is a text on the philosophy and practice of astrology, written in the 2nd century AD by the Alexandrian ...

'', as well as the ''Handy Tables'', the ''Canobic Inscription'', and other minor works.

Ptolemaic astronomy

The ''Almagest'' is one of the most influential books in the history of Western astronomy. In this book, Ptolemy explained how to predict the behavior of the planets, as Hipparchus could not, with the introduction of a new mathematical tool, theequant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

. The ''Almagest'' gave a comprehensive treatment of astronomy, incorporating theorems, models, and observations from many previous mathematicians. This fact may explain its survival, in contrast to more specialized works that were neglected and lost. Ptolemy placed the planets in the order that would remain standard until it was displaced by the heliocentric system and the Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the Universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" bene ...

:

# Moon

# Mercury

# Venus

# Sun

# Mars

# Jupiter

# Saturn

# Fixed stars

The extent of Ptolemy's reliance on the work of other mathematicians, in particular his use of Hipparchus' star catalogue, has been debated since the 19th century. A controversial claim was made by Robert R. Newton in the 1970s. in ''The Crime of Claudius Ptolemy'', he argued that Ptolemy faked his observations and falsely claimed the catalogue of Hipparchus as his own work. Newton's theories have not been adopted by most historians of astronomy.

Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importa ...

of Alexandria performed a deep examination of the shape and motion of the Earth and celestial bodies. He worked at the museum, or instructional center, school and library of manuscripts in Alexandria. Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

is responsible for a lot of concepts, but one of his most famous works summarizing these concepts is the Almagest, a series of 13 books where he presented his astronomical theories. Ptolemy discussed the idea of epicycles and center of the world. The epicycle center moves at a constant rate in a counter clockwise direction. Once other celestial bodies, such as the planets, were introduced into this system, it became more complex. The models for Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars included the center of the circle, the equant point, the epicycle, and an observer from earth to give perspective. The discovery of this model was that the center of the Mercury and Venus epicycles must always be colinear with the Sun. This assures of bounded elongation. (Bowler, 2010, 48) Bounded elongation is the angular distance of celestial bodies from the center of the universe. Ptolemy's model of the cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

and his studies landed him an important place in history in the development of modern-day science.

The cosmos was a concept further developed by Ptolemy that included equant circles, however Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

model of the universe was simpler. In the Ptolemaic system, the Earth was at the center of the universe with the Moon, the Sun, and five planets circling it. The circle of fixed stars marked the outermost sphere of the universe and beyond that would be the philosophical “aether” realm. The Earth was at the exact center of the cosmos, most likely because people at the time believed the Earth had to be at the center of the universe because of the deductions made by observers in the system. The sphere carrying the Moon is described as the boundary between the corruptible and changing sublunary world and the incorruptible and unchanging heavens above it (Bowler, 2010, 26). The heavens were defined as incorruptible and unchanging based on theology and mythology of the past.

The Almagest introduced the idea of the sphericity of heavens. The assumption is that the sizes and mutual distances of the stars must appear to vary however one supposes the earth to be positioned, yet no such variation occurred (Bowler, 2010, 55), The aether is the area that describes the universe above the terrestrial sphere. This component of the atmosphere is unknown and named by philosophers, though many do not know what lies beyond the realm of what has been seen by human beings. The aether is used to affirm the sphericity of the heavens and this is confirmed by the belief that different shapes have an equal boundary and those with more angles are greater, the circle is greater than all other surfaces, and a sphere greater than all other solids. Therefore, through physical considerations, and heavenly philosophy, there is an assumption that the heavens must be spherical. The Almagest also suggested that the earth was spherical because of similar philosophy. The differences in the hours across the globe are proportional to the distances between the spaces at which they are being observed. Therefore, it can be deduced that the Earth is spherical because of the evenly curving surface and the differences in time that was constant and proportional. In other words, the Earth must be spherical because they change in time-zones across the world occur in a uniform fashion, as with the rotation of a sphere. The observation of eclipses further confirmed these findings because everyone on Earth could see a lunar eclipse, for example, but it would be at different hours.

The ''Almagest'' also suggest that the Earth is at the center of the universe. The basis on which this is found is in the fact that six zodiac signs can be seen above Earth, while at the same time the other signs are not visible (Bowler, 2010, 57). The way that we observe the increase and decrease of daylight would be different if the Earth was not at the center of the universe. Though this view later proofed to be invalid, this was a good proponent to the discussion of the design of the universe. Ideas on the universe were later developed and advanced through the works of other philosophers such as Copernicus, who built on ideas through his knowledge of the world and God.

A few mathematicians of Late Antiquity wrote commentaries on the ''Almagest'', including Pappus of Alexandria

Pappus of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Πάππος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; AD) was one of the last great Greek mathematicians of antiquity known for his ''Synagoge'' (Συναγωγή) or ''Collection'' (), and for Pappus's hexagon theorem i ...

as well as Theon of Alexandria

Theon of Alexandria (; grc, Θέων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; 335 – c. 405) was a Greek scholar and mathematician who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. He edited and arranged Euclid's '' Elements'' and wrote commentaries on wor ...

and his daughter Hypatia

Hypatia, Koine pronunciation (born 350–370; died 415 AD) was a neoplatonist philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician, who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, then part of the Eastern Roman Empire. She was a prominent thinker in Alexandria where ...

. Ptolemaic astronomy became standard in medieval western European and Islamic astronomy

Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age (9th–13th centuries), and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle ...

until it was displaced by Maraghan, heliocentric and Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the Universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" bene ...

s by the 16th century. However, recently discovered manuscripts reveal that Greek astrologers

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

of Antiquity continued using pre-Ptolemaic methods for their calculations (Aaboe, 2001).

Influence on Indian astronomy

Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

astronomy is known to have been practiced near India in the Greco-Bactrian

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the India ...

city of Ai-Khanoum

Ai-Khanoum (, meaning ''Lady Moon''; uz, Oyxonim) is the archaeological site of a Hellenistic city in Takhar Province, Afghanistan. The city, whose original name is unknown, was probably founded by an early ruler of the Seleucid Empire and se ...

from the 3rd century BC. Various sun-dials, including an equatorial sundial adjusted to the latitude of Ujjain

Ujjain (, Hindustani pronunciation: �d͡ːʒɛːn is a city in Ujjain district of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It is the fifth-largest city in Madhya Pradesh by population and is the administrative centre of Ujjain district and Ujjain ...

have been found in archaeological excavations there. Numerous interactions with the Mauryan Empire, and the later expansion of the Indo-Greeks

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era Ancient Greece, Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern r ...

into India suggest that some transmission may have happened during that period.

Several Greco-Roman astrological treatises are also known to have been imported into India during the first few centuries of our era. The ''Yavanajataka

The Yavanajātaka (Sanskrit: ''yavana'' 'Greek' + ''jātaka'' ' nativity' = 'nativity according to the Greeks'), written by Sphujidhvaja, is an ancient text in Indian astrology.

According to David Pingree, it is a later versification of an earl ...

'' ("Sayings of the Greeks") was translated from Greek to Sanskrit by Yavanesvara

The Yavanajātaka (Sanskrit: ''yavana'' 'Greek' + ''jātaka'' ' nativity' = 'nativity according to the Greeks'), written by Sphujidhvaja, is an ancient text in Indian astrology.

According to David Pingree, it is a later versification of an earl ...

during the 2nd century, under the patronage of the Western Satrap

The Western Satraps, or Western Kshatrapas (Brahmi:, ''Mahakṣatrapa'', "Great Satraps") were Indo-Scythian (Saka) rulers of the western and central part of India ( Saurashtra and Malwa: modern Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh ...

Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who hist ...

king Rudradaman I

Rudradāman I (r. 130–150) was a Śaka ruler from the Western Kshatrapas dynasty. He was the grandson of the king Caṣṭana. Rudradāman I was instrumental in the decline of the Sātavāhana Empire. Rudradāman I took up the title of ''Mah ...

. Rudradaman's capital at Ujjain "became the Greenwich of Indian astronomers and the Arin of the Arabic and Latin astronomical treatises; for it was he and his successors who encouraged the introduction of Greek horoscopy and astronomy into India."

Later in the 6th century, the ''Romaka Siddhanta

The ''Romaka Siddhanta'' (), literally "The Doctrine of the Romans", is one of the five siddhantas mentioned in Varahamihira's ''Panchasiddhantika'' which is an Indian astronomical treatise.

Content

It is the only one of all Indian astronomical ...

'' ("Doctrine of the Romans"), and the ''Paulisa Siddhanta

The Pauliṣa Siddhānta (literally, "The scientific-treatise of Pauliṣa Muni") refers to multiple Indian astronomical treatises, at least one of which is based on a Western source. "'' Siddhānta''" literally means "doctrine" or "tradition".

It ...

'' (sometimes attributed as the "Doctrine of Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

" or in general the Doctrine of Paulisa muni) were considered as two of the five main astrological treatises, which were compiled by Varahamihira in his ''Pañca-siddhāntikā'' ("Five Treatises"). Varahamihira wrote in the Brihat-Samhita: "For, the Greeks are foreigners. This science is well established among them. Although they are revered as sages, how much more so is a twice-born person who knows the astral science."":Mleccha hi yavanah tesu samyak shastram idam sthitam

:Rsivat te api pujyante kim punar daivavid dvijah

:-(Brhatsamhita 2.15)

Sources for Greek astronomy

Many Greek astronomical texts are known only by name, and perhaps by a description or quotations. Some elementary works have survived because they were largely non-mathematical and suitable for use in schools. Books in this class include the ''Phaenomena'' ofEuclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

and two works by Autolycus of Pitane

Autolycus of Pitane ( el, Αὐτόλυκος ὁ Πιταναῖος; c. 360 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek astronomer, mathematician, and geographer. The lunar crater Autolycus was named in his honour.

Life and work

Autolycus was born in Pitane, ...

. Three important textbooks, written shortly before Ptolemy's time, were written by Cleomedes, Geminus

Geminus of Rhodes ( el, Γεμῖνος ὁ Ῥόδιος), was a Greek astronomer and mathematician, who flourished in the 1st century BC. An astronomy work of his, the ''Introduction to the Phenomena'', still survives; it was intended as an int ...

, and Theon of Smyrna

Theon of Smyrna ( el, Θέων ὁ Σμυρναῖος ''Theon ho Smyrnaios'', ''gen.'' Θέωνος ''Theonos''; fl. 100 CE) was a Greek philosopher and mathematician, whose works were strongly influenced by the Pythagorean school of thought. Hi ...

. Books by Roman authors like Pliny the Elder and Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

contain some information on Greek astronomy. The most important primary source is the ''Almagest'', since Ptolemy refers to the work of many of his predecessors (Evans 1998, p. 24).

Famous astronomers of antiquity

In addition to the authors named in the article, the following list of people who worked on mathematical astronomy or cosmology may be of interest. *Aglaonice

Aglaonice or Aganice of Thessaly ( grc, Ἀγλαονίκη, ''Aglaoníkē'', compound of αγλαὸς (''aglaòs'') "luminous" and νίκη (''nikē'') "victory") was a Greek astronomer and thaumaturge of the 2nd or 1st century BC.Pe ...

* Anaxagoras

* Archimedes

* Archytas

* Aristaeus

A minor god in Greek mythology, attested mainly by Athenian writers, Aristaeus (; ''Aristaios'' (Aristaîos); lit. “Most Excellent, Most Useful”), was the culture hero credited with the discovery of many useful arts, including bee-keepin ...

* Aristarchus

* Aristyllus

* Callippus

Callippus (; grc, Κάλλιππος; c. 370 BC – c. 300 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician.

Biography

Callippus was born at Cyzicus, and studied under Eudoxus of Cnidus at the Academy of Plato. He also worked with Aristotle at th ...

* Cleostratus

Cleostratus ( el, Κλεόστρατος; b. c. 520 BC; d. possibly 432 BC) was an astronomer of ancient Greece. He was a native of Tenedos. He is believed by ancient historians to have introduced the zodiac (beginning with Aries and Sagittarius ...

* Conon of Samos

Conon of Samos ( el, Κόνων ὁ Σάμιος, ''Konōn ho Samios''; c. 280 – c. 220 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician. He is primarily remembered for naming the constellation Coma Berenices.

Life and work

Conon was born on Samos ...

* Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

* Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

* Hephaestio

Hephaestio of Thebes (born AD 380) was an ancient writer on astrology. He wrote the ''Apotelesmatics'', which relies heavily on the work of Ptolemy and Dorotheus of Sidon

Dorotheus of Sidon ( grc-gre, Δωρόθεος Σιδώνιος, c. 75 CE ...

* Heraclides Ponticus

* Hicetas

Hicetas ( grc, Ἱκέτας or ; c. 400 – c. 335 BC) was a Greek philosopher of the Pythagorean School. He was born in Syracuse. Like his fellow Pythagorean Ecphantus and the Academic Heraclides Ponticus, he believed that the daily movemen ...

* Hippocrates of Chios

Hippocrates of Chios ( grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Χῖος; c. 470 – c. 410 BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician, geometer, and astronomer.

He was born on the isle of Chios, where he was originally a merchant. After some misadve ...

* Macrobius

* Martianus Capella

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a nati ...

* Menelaus of Alexandria

Menelaus of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Μενέλαος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς, ''Menelaos ho Alexandreus''; c. 70 – 140 CE) was a GreekEncyclopædia Britannica "Greek mathematician and astronomer who first conceived and defined a spheric ...

(

Menelaus theorem

Menelaus's theorem, named for Menelaus of Alexandria, is a proposition about triangles in plane geometry. Suppose we have a triangle ''ABC'', and a Transversal (geometry), transversal line that crosses ''BC'', ''AC'', and ''AB'' at points ''D'', ...

)

* Meton of Athens

Meton of Athens ( el, Μέτων ὁ Ἀθηναῖος; ''gen''.: Μέτωνος) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, geometer, and engineer who lived in Athens in the 5th century BC. He is best known for calculations involving the eponymou ...

* Parmenides

* Porphyry

* Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher nativ ...

* Proclus

* Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

* Theodosius of Bithynia

Theodosius of Bithynia ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος; c. 169 BCc. 100 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician who wrote the ''Sphaerics'', a book on the geometry of the sphere.

Life

Born in Tripolis, in Bithynia, Theodosius was m ...

See also

*Astronomy instruments

Astronomical instruments include:

*Alidade

*Armillary sphere

*Astrarium

*Astrolabe

*Astronomical clock

*the Antikythera mechanism, an astronomical clock

*Blink comparator

*Bolometer

*the Canterbury Astrolabe Quadrant

*Celatone

*Celestial sphere

*C ...

*Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism ( ) is an Ancient Greek hand-powered orrery, described as the oldest example of an analogue computer used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses decades in advance. It could also be used to track the four-yea ...

* Greek mathematics

* History of astronomy

* Babylonian influence on Greek astronomy

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * Bowler, Peter J., and Iwan Rhys Morus. Making Modern Science: A Historical Survey. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2010.External links

Almagest Planetary Model Animations

{{DEFAULTSORT:Greek Astronomy

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

Early scientific cosmologies