Helen Millar Craggs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Helen Millar Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence (née Craggs; 1888–1969) was a suffragette and pharmacist.

Helen Millar Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence (née Craggs; 1888–1969) was a suffragette and pharmacist.

Helen Millar Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence (née Craggs; 1888–1969) was a suffragette and pharmacist.

Helen Millar Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence (née Craggs; 1888–1969) was a suffragette and pharmacist.

Life and activism

Craggs was born in Westminster, London in 1888, daughter to Sir John Craggs, an accountant, who donate money for tropical medicine research, and she had seven siblings. Craggs was educated atRoedean

Roedean is a village in the city of Brighton and Hove, England, UK, east of the seaside resort of Brighton.

Notable buildings and areas

Roedean Gap is a slight dip in the cliffs between Black Rock and Ovingdean Gap, and has been known by the ...

and wished to study medicine, but her father refused that idea and Craggs went to teach science and physical exercise at her formed school for a time. Although Craggs' mother supported suffragism and was a lead committee member in the national and Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensington Garden ...

Conservative and Unionist Women's Franchise Association

The Conservative and Unionist Women's Franchise Association (CUWFA) was a British women's suffrage organisation open to members of the Conservative and Unionist Party. Formed in 1908 by members of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, C ...

, she deplored activism.

Craggs used a pseudonym 'Helen Millar' (perhaps to protect her family and her teaching post) when she joined the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership an ...

activists during the Peckham election in 1908. She was chalking pavements and handing out campaigning literature on the women's suffrage. Craggs assisted Flora Drummond

Flora McKinnon Drummond (née Gibson) (born 4 August 1878, Manchester – died 17 January 1949, Carradale), was a British suffragette. Nicknamed 'The General' for her habit of leading Women's Rights marches wearing a military style uniform 'wit ...

with the aim of ousting Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

in the successful campaigning wiping out his majority on this and other equality themes during the election in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

. Churchill was then put forwards for the Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

seat, where WSPU were ready to challenge him again

Within two years, Craggs had to leave an unsympathetic home to become a full time WSPU organiser at 25 shillings per month, living in rented property in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest ...

. Craggs was joined at the Women's Press shop by Mary Richardson

Mary Raleigh Richardson (1882/3 – 7 November 1961) was a Canadian suffragette active in the women's suffrage movement in the United Kingdom, an arsonist, a socialist parliamentary candidate and later head of the women's section of the Br ...

who spoke about the obscene abuse whispered by male 'bystanders' and others who came in to tear up the suffrage materials.

The Museum of London

The Museum of London is a museum in London, covering the history of the UK's capital city from prehistoric to modern times. It was formed in 1976 by amalgamating collections previously held by the City Corporation at the Guildhall Museum (fou ...

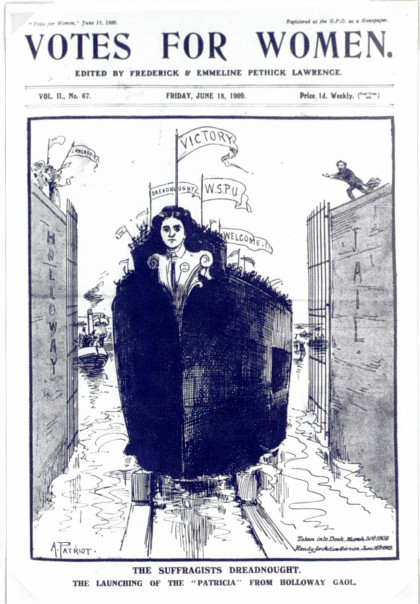

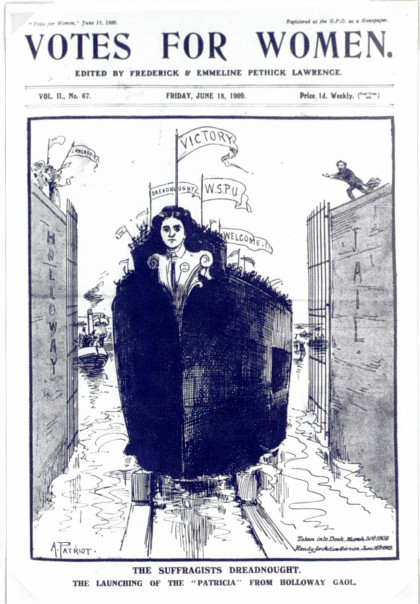

has an image of Craggs on a horsedrawn carriage for distributing the ''Votes for Women

A vote is a formal method of choosing in an election.

Vote(s) or The Vote may also refer to:

Music

*''V.O.T.E.'', an album by Chris Stamey and Yo La Tengo, 2004

*"Vote", a song by the Submarines from ''Declare a New State!'', 2006

Television

* " ...

'' newspaper.

Craggs was close to Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

's son Harry, who suffered from polio, and visited his nursing home throughout and was with him when he died in January 1910. Craggs became organiser, after Grace Roe

Eleanor Grace Watney Roe (1885–1979) was Head of Suffragette operations for the Women's Social and Political Union. She was released from prison after the outbreak of World War I due to an amnesty for suffragettes negotiated with the govern ...

, at Brixton

Brixton is a district in south London, part of the London Borough of Lambeth, England. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. Brixton experienced a rapid rise in population during the 19th cent ...

WSPU branch, and later at Hamstead. Within the movement, Craggs befriended Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended t ...

, Evelyn Sharp Evelyn Sharp may refer to:

* Evelyn Sharp (aviator) (1919–1944), American aviator

* Evelyn Sharp (businesswoman) (died 1997), American hotelier

* Evelyn Sharp (suffragist) (1869–1955), British suffragist and author

* Evelyn Sharp, Baroness Shar ...

and Beatrice Harradan. Craggs also spent time with Marie Newby in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

influencing the campaign there. Craggs was also in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

and identified as the protester who jumped out at the Home Secretary at Llandaff Cathedral

Llandaff Cathedral ( cy, Eglwys Gadeiriol Llandaf) is an Anglican cathedral and parish church in Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales. It is the seat of the Bishop of Llandaff, head of the Church in Wales Diocese of Llandaff. It is dedicated to Saint Peter ...

during a Royal Visit at Cathays Park

Cathays Park ( cy, Parc Cathays) or Cardiff Civic Centre is a civic centre area in the city centre of Cardiff, the capital city of Wales, consisting of a number of early 20th century buildings and a central park area, Alexandra Gardens. It i ...

saying 'it was a shame he was going about the country while suffragettes where starving in prison'

In November 1910, Craggs went to the Paragon Theatre, Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

at 2a.m. to hide in the freezing roofspace overnight before Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

was due to speak. Craggs broke through the crowd from her hideout shouting at the Chancellor about women's rights, and was thrown brutally down a stone staircase. A bystanding man who said 'women pay taxes too' was beaten.

Cardiff University

, latin_name =

, image_name = Shield of the University of Cardiff.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms of Cardiff University

, motto = cy, Gwirionedd, Undod a Chytgord

, mottoeng = Truth, Unity and Concord

, established = 1 ...

Archive has an image of Craggs from the ''Daily Sketch

The ''Daily Sketch'' was a British national tabloid newspaper, founded in Manchester in 1909 by Sir Edward Hulton.

It was bought in 1920 by Lord Rothermere's Daily Mirror Newspapers, but in 1925 Rothermere sold it to William and Gomer Berr ...

'' in 1912.

In 1912, Craggs was imprisoned in Holloway Prison

HM Prison Holloway was a closed category prison for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, until its closure in 2016.

Histor ...

for smashing windows and went on hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

. Later Craggs was arrested for carrying materials for causing arson, near Nuneham Courtney

Nuneham Courtenay is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish about southeast of Oxford. It occupies a pronounced section of the left bank of the River Thames.

Geography

The parish is bounded to the west by the River Thames and on ...

, the home of Government Cabinet member, Lewis Harcourt

Lewis Vernon Harcourt, 1st Viscount Harcourt (born Reginald Vernon Harcourt; 31 January 1863 – 24 February 1922), was a British Liberal Party politician who held the Cabinet post of Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1910 to 1915. Lord ...

. WSPU insisted Craggs was acting alone, as this was the first threat to property. The incident was described in detail in court about two women hiring a canoe, and surprise encounter with a policeman, to whom Craggs said they were camping nearby and had come to 'look around the house'. The constable later identified Craggs, but the second woman (Norah Smyth

Norah Lyle-Smyth (22 March 1874 – 1963) was a British suffragette, photographer and socialist activist.

Life

Smyth was born into a wealthy family, and was the niece of the composer and suffragette Ethel Smyth. Until his death in 1912 her ...

) escaped and police found food and WSPU flag colours (white green and purple) and phone numbers of the property and the Oxford Fire Station. Craggs wore ' a striking costume prominently displaying the suffragist colours' when she appeared in Bullingdon Petty Sessions court the next day and admitted her intent would not give her name. Craggs was held in remand due to the seriousness of the crime (as 8 people were in the house) and sentenced at the Assizes

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes e ...

court in Oxford, bailed at £1000, half was provided by Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended t ...

. Craggs was sent for 9 months with hard labour in Oxford Prison

Oxford Castle is a large, partly ruined medieval castle on the western side of central Oxford in Oxfordshire, England. Most of the original moated, wooden motte and bailey castle was replaced in stone in the late 12th or early 13th century and ...

, and wrote thanking Hugh Franklin for allegedly getting photographs of the property. Craggs was moved to Holloway Prison

HM Prison Holloway was a closed category prison for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, until its closure in 2016.

Histor ...

, again went on hunger strike and was force fed

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into t ...

five times in two days and suffered internal and external bruising for 11 days then released due to her health. Lewis Harcourt gave £1000 donation to the League for Opposing Women's Suffrage.

Craggs moved to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

where she trained at the Rotunda Hospital

The Rotunda Hospital ( ga, Ospidéal an Rotunda; legally the Hospital for the Relief of Poor Lying-in Women, Dublin) is a maternity hospital on Parnell Street in Dublin, Ireland, now managed by RCSI Hospitals. The eponymous Rotunda in Parnell S ...

as a midwife

A midwife is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialization known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughout their lifespan; co ...

, married a London East End

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

General practitioner, Duncan Alexander McCrombie, from Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

. Her parents did not attend the wedding in 1914. Craggs trained as a pharmacist to support her husband's practice. Craggs was widowed in 1936, at a young age, starting in business making jigsaws as a means of earning income for her two children, Sarah (Sallie) (born in 1923) and John Alexander Somerville (born in 1925).

Later life

AfterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Craggs and her daughter emigrated to North America, settling in Canada, and saw Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British suffragette born in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bord ...

sometimes in Los Angeles Craggs returned to London became private secretary and then the second wife to Lord Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, a long-standing suffrage movement leader and sponsor from Surrey, three years after his first wife suffragette Emmeline

''Emmeline, The Orphan of the Castle'' is the first novel written by English writer Charlotte Smith; it was published in 1788. A Cinderella story in which the heroine stands outside the traditional economic structures of English society and ...

had died, on St. Valentine's Day, 14 February 1957.

In 1969, Craggs, then Baroness Helen Pethick-Lawrence, died on 15 January in Victoria, British Columbia

Victoria is the capital city of the Canadian province of British Columbia, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific coast. The city has a population of 91,867, and the Greater Victoria area has a population of 397,237. Th ...

, Canada.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Craggs, Helen Millar 1888 births 1969 deaths Women's Social and Political Union People educated at Roedean School, East Sussex Pethick-Lawrence