Hashshashin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of

The rulers of the Nizari Isma'ili State were religious leaders, at first '' da'i'' and later

The rulers of the Nizari Isma'ili State were religious leaders, at first '' da'i'' and later  While Assassins typically refers to the entire sect, only a group of disciples known as the ''

While Assassins typically refers to the entire sect, only a group of disciples known as the ''

The Assassins suffered a significant blow at the hands of the

The Assassins suffered a significant blow at the hands of the

In pursuit of their religious and political goals, the Isma'ilis adopted various military strategies popular in the Middle Ages. One such method was that of assassination, the selective elimination of prominent rival figures. The murders of political adversaries were usually carried out in public spaces, creating resounding intimidation for other possible enemies.Daftary 1998, p. 129 Throughout history, many groups have resorted to assassination as a means of achieving political ends. The assassinations were committed against those whose elimination would most greatly reduce aggression against the Ismailis and, in particular, against those who had perpetrated massacres against the community. A single assassination was usually employed in contrast with the widespread bloodshed which generally resulted from factional combat. Assassins are also said to be have been adept in ''

In pursuit of their religious and political goals, the Isma'ilis adopted various military strategies popular in the Middle Ages. One such method was that of assassination, the selective elimination of prominent rival figures. The murders of political adversaries were usually carried out in public spaces, creating resounding intimidation for other possible enemies.Daftary 1998, p. 129 Throughout history, many groups have resorted to assassination as a means of achieving political ends. The assassinations were committed against those whose elimination would most greatly reduce aggression against the Ismailis and, in particular, against those who had perpetrated massacres against the community. A single assassination was usually employed in contrast with the widespread bloodshed which generally resulted from factional combat. Assassins are also said to be have been adept in '' Marco Polo recounts the following method how the Hashashin were recruited for jihad and assassinations on behalf of their master in Alamut:

“He was named Alo−eddin, and his religion was that of Mahomet. In a beautiful valley enclosed between two lofty mountains, he had formed a luxurious garden, stored with every delicious fruit and every fragrant shrub that could be procured. Palaces of various sizes and forms were erected in different parts of the grounds, ornamented with works in gold, with paintings, and with furniture of rich silks. By means of small conduits contrived in these buildings, streams of wine, milk, honey, and some of pure water, were seen to flow in every direction. The inhabitants of these palaces were elegant and beautiful damsels, accomplished in the arts of singing, playing upon all sorts of musical instruments, dancing, and especially those of dalliance and amorous allurement. Clothed in rich dresses they were seen continually sporting and amusing themselves in the garden and pavilions, their female guardians being confined within doors and never suffered to appear. The object which the chief had in view in forming a garden of this fascinating kind, was this: that Mahomet having promised to those who should obey his will the enjoyments of Paradise, where every species of sensual gratification should be found, in the society of beautiful nymphs, he was desirous of its being understood by his followers that he also was a prophet and the compeer of Mahomet, and had the power of admitting to Paradise such as he should choose to favor. In order that none without his licence might find their way into this delicious valley, he caused a strong and inexpugnable castle to be erected at the opening of it, through which the entry was by a secret passage. At his court, likewise, this chief entertained a number of youths, from the age of twelve to twenty years, selected from the inhabitants of the surrounding mountains, who showed a disposition for martial exercises, and appeared to possess the quality of daring courage. To them he was in the daily practice of discoursing on the subject of the paradise announced by the prophet, and of his own power of granting admission; and at certain times he caused opium to be administered to ten or a dozen of the youths; and when half dead with sleep he had them conveyed to the several apartments of the palaces in the garden. Upon awakening from this state of lethargy, their senses were struck with all the delightful objects that have been described, and each perceived himself surrounded by lovely damsels, singing, playing, and attracting his regards by the most fascinating caresses, serving him also with delicate viands and exquisite wines; until intoxicated with excess of enjoyment amidst actual rivulets of milk and wine, he believed himself assuredly in Paradise, and felt an unwillingness to relinquish its delights. When four or five days had thus been passed, they were thrown once more into a state of somnolency, and carried out of the garden. Upon their being introduced to his presence, and questioned by him as to where they had been, their answer was, “In Paradise, through the favor of your highness:” and then before the whole court, who listened to them with eager curiosity and astonishment, they gave a circumstantial account of the scenes to which they had been witnesses. The chief thereupon addressing them, said: “We have the assurances of our prophet that he who defends his lord shall inherit Paradise, and if you show yourselves devoted to the obedience of my orders, that happy lot awaits you.” Animated to enthusiasm by words of this nature, all deemed themselves happy to receive the commands of their master, and were forward to die in his service. 5 The consequence of this system was, that when any of the neighboring princes, or others, gave umbrage to this chief, they were put to death by these his disciplined assassins; none of whom felt terror at the risk of losing their own lives, which they held in little estimation, provided they could execute their master's will.”

However , these methods described by Marco Polo are far from the truth (explained in the below section). It is believed by the Ismailis that the Fida'is were recruited for Jihad as it was a tenet of their faith (like other Muslims) and for their love of the Imam (Walayah).

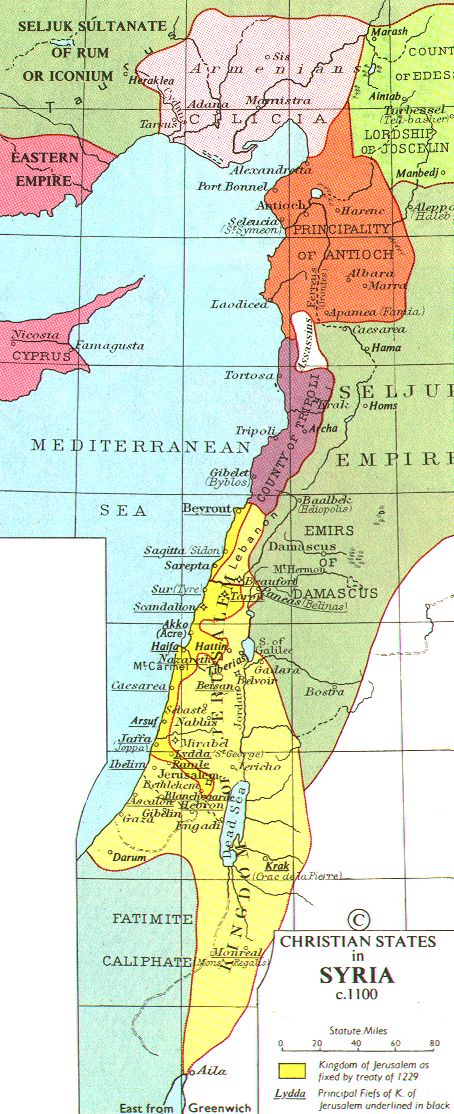

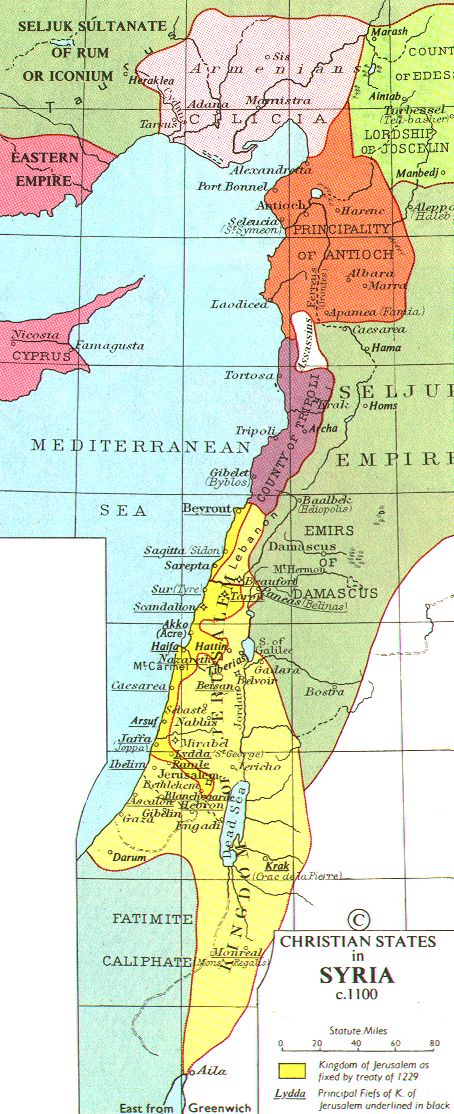

During the mid-12th century the Assassins captured or acquired several fortresses in the Nusayriyah Mountain Range in coastal Syria, including Masyaf, Rusafa, al-Kahf, al-Qadmus, Khawabi, Sarmin, Quliya,

Marco Polo recounts the following method how the Hashashin were recruited for jihad and assassinations on behalf of their master in Alamut:

“He was named Alo−eddin, and his religion was that of Mahomet. In a beautiful valley enclosed between two lofty mountains, he had formed a luxurious garden, stored with every delicious fruit and every fragrant shrub that could be procured. Palaces of various sizes and forms were erected in different parts of the grounds, ornamented with works in gold, with paintings, and with furniture of rich silks. By means of small conduits contrived in these buildings, streams of wine, milk, honey, and some of pure water, were seen to flow in every direction. The inhabitants of these palaces were elegant and beautiful damsels, accomplished in the arts of singing, playing upon all sorts of musical instruments, dancing, and especially those of dalliance and amorous allurement. Clothed in rich dresses they were seen continually sporting and amusing themselves in the garden and pavilions, their female guardians being confined within doors and never suffered to appear. The object which the chief had in view in forming a garden of this fascinating kind, was this: that Mahomet having promised to those who should obey his will the enjoyments of Paradise, where every species of sensual gratification should be found, in the society of beautiful nymphs, he was desirous of its being understood by his followers that he also was a prophet and the compeer of Mahomet, and had the power of admitting to Paradise such as he should choose to favor. In order that none without his licence might find their way into this delicious valley, he caused a strong and inexpugnable castle to be erected at the opening of it, through which the entry was by a secret passage. At his court, likewise, this chief entertained a number of youths, from the age of twelve to twenty years, selected from the inhabitants of the surrounding mountains, who showed a disposition for martial exercises, and appeared to possess the quality of daring courage. To them he was in the daily practice of discoursing on the subject of the paradise announced by the prophet, and of his own power of granting admission; and at certain times he caused opium to be administered to ten or a dozen of the youths; and when half dead with sleep he had them conveyed to the several apartments of the palaces in the garden. Upon awakening from this state of lethargy, their senses were struck with all the delightful objects that have been described, and each perceived himself surrounded by lovely damsels, singing, playing, and attracting his regards by the most fascinating caresses, serving him also with delicate viands and exquisite wines; until intoxicated with excess of enjoyment amidst actual rivulets of milk and wine, he believed himself assuredly in Paradise, and felt an unwillingness to relinquish its delights. When four or five days had thus been passed, they were thrown once more into a state of somnolency, and carried out of the garden. Upon their being introduced to his presence, and questioned by him as to where they had been, their answer was, “In Paradise, through the favor of your highness:” and then before the whole court, who listened to them with eager curiosity and astonishment, they gave a circumstantial account of the scenes to which they had been witnesses. The chief thereupon addressing them, said: “We have the assurances of our prophet that he who defends his lord shall inherit Paradise, and if you show yourselves devoted to the obedience of my orders, that happy lot awaits you.” Animated to enthusiasm by words of this nature, all deemed themselves happy to receive the commands of their master, and were forward to die in his service. 5 The consequence of this system was, that when any of the neighboring princes, or others, gave umbrage to this chief, they were put to death by these his disciplined assassins; none of whom felt terror at the risk of losing their own lives, which they held in little estimation, provided they could execute their master's will.”

However , these methods described by Marco Polo are far from the truth (explained in the below section). It is believed by the Ismailis that the Fida'is were recruited for Jihad as it was a tenet of their faith (like other Muslims) and for their love of the Imam (Walayah).

During the mid-12th century the Assassins captured or acquired several fortresses in the Nusayriyah Mountain Range in coastal Syria, including Masyaf, Rusafa, al-Kahf, al-Qadmus, Khawabi, Sarmin, Quliya,

di Michele T. Mazzucato The tales of the ''fida'is'' training collected from anti-Ismaili historians and orientalist writers were compounded and compiled in Marco Polo's account, in which he described a "secret garden of paradise".Daftary 1998, p. 16 After being drugged, the Ismaili devotees were said to be taken to a paradise-like garden filled with attractive young maidens and beautiful plants in which these ''fida'is'' would awaken. Here, they were told by an "old" man that they were witnessing their place in Paradise and that should they wish to return to this garden permanently, they must serve the Nizari cause. So went the tale of the "Old Man in the Mountain", assembled by Marco Polo and accepted by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, an 18th-century Austrian orientalist writer responsible for much of the spread of this legend. Until the 1930s, von Hammer's retelling of the Assassin legends served as the standard account of the Nizaris across Europe. A well-known legend tells how Count Henry II of Champagne, returning from

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

and in Syria, and held a strict subterfuge policy throughout the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

through the covert murder of Muslim and Christian leaders who were considered enemies of the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī State. The modern term assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

is believed to stem from the tactics used by the Assassins.

Nizārī Ismāʿīlīsm formed in the late 11th century after a succession crisis within the Fatimid Caliphate between Nizār ibn al-Mustanṣir and his half-brother, caliph al-Musta‘lī. Contemporaneous historians include Arabs ibn al-Qalanisi

Abū Yaʿlā Ḥamzah ibn al-Asad ibn al-Qalānisī ( ar, ابو يعلى حمزة ابن الاسد ابن القلانسي; c. 1071 – 18 March 1160) was an Arab politician and chronicler in 12th-century Damascus.

Biography

Abu Ya‘la ('fath ...

and Ali ibn al-Athir, and the Persian Ata-Malik Juvayni. The first two referred to the Assassins as ''batiniyya

Batiniyya ( ar, باطنية, Bāṭiniyyah) refers to groups that distinguish between an outer, exoteric ('' zāhir'') and an inner, esoteric ('' bāṭin'') meaning in Islamic scriptures. The term has been used in particular for an allegoristi ...

'', an epithet widely accepted by Ismāʿīlīs themselves.

Overview

The Nizari Isma'ili State, later known as the Assassins, was founded byHassan-i Sabbah

Hasan-i Sabbāh ( fa, حسن صباح) or Hassan as-Sabbāh ( ar, حسن بن الصباح الحميري, full name: Hassan bin Ali bin Muhammad bin Ja'far bin al-Husayn bin Muhammad bin al-Sabbah al-Himyari; c. 1050 – 12 June 1124) was the ...

. The state was formed in 1090 after the capture of Alamut Castle

Alamut ( fa, الموت, meaning "eagle's nest") is a ruined mountain fortress located in the Alamut region in the South Caspian province of Qazvin near the Masoudabad region in Iran, approximately 200 km (130 mi) from present-day Te ...

in modern Iran, which served as the Assassins' headquarters. The Alamut and Lambsar castles became the foundation of a network of Isma'ili fortresses throughout Persia and Syria that formed the backbone of Assassin power, and included Syrian strongholds at Masyaf, Abu Qubays Abu Qubays may refer to the following places:

* Abu Qubays (mountain), a mountain near Mecca, Saudi Arabia

*Abu Qubays, Syria

Abu Qubays ( ar, أبو قبيس also spelled ''Abu Qobeis'', ''Abu Qubais'' or ''Bu Kubais''; also known as Qartal) is ...

, al-Qadmus and al-Kahf. The Nizari Isma'ili State was ruled by Hassan-i Sabbah until his death in 1124. The Western world was introduced to the Assassins by the works of Marco Polo who understood the name as deriving from the word hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a cannabis (drug), drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. Eu ...

.

The rulers of the Nizari Isma'ili State were religious leaders, at first '' da'i'' and later

The rulers of the Nizari Isma'ili State were religious leaders, at first '' da'i'' and later Imams

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

''.'' Prominent Assassin leaders operating in Syria included al-Hakim al-Munajjim, the physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

-astrologer

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

(d. 1103), Abu Tahir al-Sa’igh, the goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Nowadays they mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, goldsmiths have also made silverware, platters, goblets, decorative and servicea ...

(d. 1113), Bahram al-Da'i (d. 1127), and Rashid ad-Din Sinan, renowned as the greatest Assassin chief (d. 1193). While Assassins typically refers to the entire sect, only a group of disciples known as the ''

While Assassins typically refers to the entire sect, only a group of disciples known as the ''fida'i

"" ( ar, فدائي ; lit. " Fedayeen warrior"), is the national anthem of Palestine.

History

The anthem was adopted by the Palestinian Liberation Organization in 1996, in accordance with Article 31 of the Palestinian Declaration of Independenc ...

'' actually engaged in conflict. Lacking their own army, the Nizari relied on these warriors to carry out espionage and assassinations of key enemy figures. The preferred method of killing was by dagger, nerve poison or arrows. The Assassins posed a substantial strategic threat to Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muh ...

, Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

, and Seljuk authority. Over the course of nearly 300 years, they killed hundreds - including three caliphs, a ruler of Jerusalem and several Muslim and Christian leaders. The first instance of murder in the effort to establish a Nizari Isma'ili state in Persia was the assassination of Seljuk vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called '' katib'' (secretary), who was ...

Nizam al-Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising ...

in 1092.

Other notable victims of the Assassins include Janah ad-Dawla, emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

of Homs, (1103), Mawdud ibn Altuntash, atabeg of Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second large ...

(1113), Fatimid vizier Al-Afdal Shahanshah (1121), Seljuk atabeg Aqsunqur al-Bursuqi (1126), Fatimid caliph al-Amir bi-Ahkami’l-Lah (1130), Taj al-Mulk Buri

Taj al-Muluk Buri ( ar, تاج الملوك بوري; died 6 June 1132) was an atabeg of Damascus from 1128 to 1132. He was initially an officer in the army of Duqaq, the Seljuk ruler of Damascus, together with his father Toghtekin. When the lat ...

, atabeg of Damascus (1132), and Abbasid caliphs al-Mustarshid

Abu Mansur al-Faḍl ibn Ahmad al-Mustazhir ( ar, أبو منصور الفضل بن أحمد المستظهر; 1092 – 29 August 1135) better known by his regnal name Al-Mustarshid Billah ( ar, المسترشد بالله) was the Abbasid calip ...

(1135) and ar-Rashid (1138). Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

, a major foe of the Assassins, escaped assassination twice (1175–1176). The first Frank known to have been killed by the Assassins was Raymond II, Count of Tripoli

Raymond II ( la, Raimundus; 1116 – 1152) was count of Tripoli from 1137 to 1152. He succeeded his father, Pons, Count of Tripoli, who was killed during a campaign that a commander from Damascus launched against Tripoli. Raymond accused the l ...

, in 1152. The Assassins were acknowledged and feared by the Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, losing the ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' King of Jerusalem

The King of Jerusalem was the supreme ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Crusader states, Crusader state founded in Jerusalem by the Latin Church, Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade, when the city was Siege of Jerusalem (1099), conqu ...

, Conrad of Montferrat

Conrad of Montferrat ( Italian: ''Corrado del Monferrato''; Piedmontese: ''Conrà ëd Monfrà'') (died 28 April 1192) was a nobleman, one of the major participants in the Third Crusade. He was the ''de facto'' King of Jerusalem (as Conrad I) by ...

, to an Assassin's blade in 1192 and Lord Philip of Montfort of Tyre in 1270.

During the rule of Imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, se ...

Rukn al-Din Khurshah, the Nizari Isma'ili State declined internally, and was eventually destroyed as Khurshah surrendered the castles after the Mongol invasion of Persia

The Mongol conquest of Persia comprised three Mongol campaigns against Islamic states in the Middle East and Central Asia between 1219 and 1256. These campaigns led to the termination of the Khwarazmian dynasty, the Nizari Ismaili state, an ...

. Khurshah died in 1256 and, by 1275, the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

had destroyed and eliminated the order of Assassins.

Accounts of the Assassins were preserved within Western, Arabic, Syriac, and Persian sources where they are depicted as trained killers, responsible for the systematic elimination of opposing figures. European orientalists in the 19th and 20th centuries also referred to the Isma'ili Assassins in their works, writing about them based on accounts in seminal works by medieval Sunni Arab and Persian authors, particularly ibn al-Qalanisi's '' Mudhayyal Ta'rikh Dimashq'' (''Continuation of the Chronicle of Damascus''), ibn al-Athir's '' al-Kāmil fit-Tārīkh'' (''The Complete History''), and Juvayni's '' Tarīkh-i Jahān-gushā'' (''History of the World Conqueror'')''.''

Origins

Hassan-i Sabbah

Hasan-i Sabbāh ( fa, حسن صباح) or Hassan as-Sabbāh ( ar, حسن بن الصباح الحميري, full name: Hassan bin Ali bin Muhammad bin Ja'far bin al-Husayn bin Muhammad bin al-Sabbah al-Himyari; c. 1050 – 12 June 1124) was the ...

was born in Qom

Qom (also spelled as "Ghom", "Ghum", or "Qum") ( fa, قم ) is the seventh largest metropolis and also the seventh largest city in Iran. Qom is the capital of Qom Province. It is located to the south of Tehran. At the 2016 census, its popul ...

, ca. 1050, and did his religious studies in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

with the Fatimids. Sabbah's father was a Qahtanite

The terms Qahtanite and Qahtani ( ar, قَحْطَانِي; transliterated: Qaḥṭānī) refer to Arabs who originate from South Arabia. The term "Qahtan" is mentioned in multiple ancient Arabian inscriptions found in Yemen. Arab traditions ...

Arab, said to be a descendant of Himyaritic kings, having emigrated to Qom from Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Naja ...

. His support of Nizar ibn al-Mustansir in the succession crisis resulted in his imprisonment and deportation. He made his way to Persia where, through subterfuge, he and his followers captured Alamut Castle in 1090. This was the beginning of the Nizari Isma'ili State and the Assassins. Hassan-i Sabbah was not a direct descendant of Nizar and so a ''da'i'' rather than an Imam. It was Isma'ili doctrine that he kept Nizar's lineage intact through the so-called "concealed Imams". Sabbah adapted the fortress to suit his needs not only for defense from hostile forces, but also for indoctrination of his followers. After laying claim to the fortress at Alamut, Sabbah began expanding his influence outwards to nearby towns and districts, using his agents to gain political favour and to intimidate the local populations. Spending most of his days at Alamut producing religious works and developing doctrines for his order, Sabbah would never again leave his fortress. Murder for religious purposes was not new to the region, as the strangler sects of southern Iraq dating to the eighth century have shown. The strangler sects were stopped by the Umayyads; the Assassins would not be by the later caliphates.

Shortly after establishing their headquarters at Alamut Castle, the sect captured Lambsar Castle, to be the largest of the Isma'ili fortresses and confirming the Assassins' power in northern Persia. The estimated date of the capture of Lambsar varies between 1096 and 1102. The castle was taken under the command of Kiya Buzurg Ummid

Kiyā Buzurg-Ummīd ( fa, کیا بزرگ امید; died 1138) was a ''dawah, dāʿī'' and the second ruler (''da'i'') of the Nizari Ismaili state#Rulers and Imams, Nizari Isma'ili State, ruling Alamut Castle from 1124 to 1138 CE (or 518—532 A ...

, later Sabbah's successor, who remained commandant of the fortress for twenty years. No interactions between the Christian forces of the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

and the Assassins have been noted, with the latter concentrating on the Muslim enemies of the former. Other than a mention of Tancred's 1106 taking of Apamea (see below) in ''Gesta Tancredi ''Gesta Tancredi in expeditione Hierosolymitana'' (The Deeds of Tancred in the Crusade), also known by its full title ''Gesta Tancredi Siciliae Regis in expeditione Hierosolymitana, is'' usually called simply ''Gesta Tancredi'', is a prosimetric hi ...

'', Western Europe likely first learned of the Assassins from the chronicles of William of Tyre

William of Tyre ( la, Willelmus Tyrensis; 113029 September 1186) was a medieval prelate and chronicler. As archbishop of Tyre, he is sometimes known as William II to distinguish him from his predecessor, William I, the Englishman, a forme ...

, ''A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea,'' published much later. William coined the phrase "Old Man of the Mountain" to describe the Nizari Isma'ili ''da'i'' at Alamut.

The Assassins were immediately threatened by the forces of Seljuk sultan Malik-Shah I, marking the beginning of the Nizari-Seljuk wars. One of Sabbah's disciples named Dihdar Bu-Ali from Qazvin

Qazvin (; fa, قزوین, , also Romanized as ''Qazvīn'', ''Qazwin'', ''Kazvin'', ''Kasvin'', ''Caspin'', ''Casbin'', ''Casbeen'', or ''Ghazvin'') is the largest city and capital of the Province of Qazvin in Iran. Qazvin was a capital of the ...

rallied local supporters to deflect the Seljuks. Their attack on Alamut Castle and surrounding areas was canceled upon the death of the sultan. The new sultan Barkiyaruq, son of Malik-Shah I, did not continue the direct attack on Alamut, concentrating on securing his position against rivals, including his half-brother Muhammad I Tapar

Abu Shuja Ghiyath al-Dunya wa'l-Din Muhammad ibn Malik-Shah ( fa, , Abū Shujāʿ Ghiyāth al-Dunyā wa ’l-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Malik-Šāh; 1082 – 1118), better known as Muhammad I Tapar (), was the sultan of the Seljuk Empire from 1105 to 111 ...

, who eventually settled for a smaller role, becoming '' malik'' (translated as "king") in Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

and Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

.

The first notable assassination was that of powerful Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising ...

in 1092, who had helped propel Barkiyaruq to lead the sultanate. Sabbah is reputed to have remarked, "the killing of this devil is the beginning of bliss" on hearing to the death of Nizam. Of the 50 assassinations conducted during Sabbah's reign, more than half were Seljuk officials, many of whom supported Muhammad I Tapar. The story (presented here) claiming a friendship among Nizam al-Mulk, Hassan-i Sabbah and Omar Khayyam described by Edward FitzGerald in his translation of '' The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam'' is most certainly false.

The Assassins seized Persian castles of Rudkhan and Gerdkuh in 1096, before turning to Syria. Gerdkuh was re-fortified by Mu'ayyad al-Din Muzaffar ibn Ahmad Mustawfi, a Seljuk who was a secret Isma'ili convert, and his son Sharaf al-Din Muhammad. There they occupied the fortress at Shaizar held by the Banu Munqidh, using it to spread terror to Isfahan, the heart of the Seljuk Empire. A rebellion by the local population drove the Assassins out, but they continued to occupy a smaller fortress at Khalinjan. In 1097, Barkiyaruq associate Bursuq was killed by Assassins.

By 1100, Barkiyaruq had consolidated his power, and the Assassins increased their presence by infiltrating the sultan's court and army. Day-to-day functions of the court were frequently performed while armored and with weapons. The next year, he tasked his brother Ahmad Sanjar, then ruler of Khorasan, to attack Assassin strongholds in Quhistan. The siege at Tabas was at first successful, with the walls of the fortress breached, but then was lifted, possibly because the Seljuk commander had been bribed. The subsequent attack was devastating to the Assassins, but the terms granted were generous and they were soon reestablished at both Quhistan and Tabas. In the years following, the Assassins continued their mission against religious and secular leaders. Given these successes, they began expanding their operations into Syria.

Expansion into Syria

The first ''da'i'' Hassan-i dispatched to Syria was al-Hakim al-Munajjim, a Persian known as the physician-astrologer, establishing a cell in Aleppo in the early 12th century. Ridwan, the emir of Aleppo, was in search of allies and worked closely with al-Hakim leading to speculation that Ridwan himself was a Nizari. The alliance was first shown in the assassination in 1103 of Janah ad-Dawla, emir of Homs and a key opponent of Ridwan. He was murdered by three Assassins at the Great Mosque of al-Nuri in Homs. Al-Hakim died a few weeks later and was succeeded by Abu Tahir al-Sa’igh, a Persian known as the goldsmith. After the death of Barkiyaruq in 1105, his successor Muhammad I Tapar began his anti-Nizari campaign. While successful in cleaning the Assassins out of parts of Persia, they remained untouchable in their strongholds in the north. An eight-year war of attrition was initiated under the command ofAhmad ibn Nizam al-Mulk

Ḍiyaʾ al-Mulk Aḥmad ibn Niẓām al-Mulk ( fa, ضیاءالملک احمد بن نظامالملک), was a Persian vizier of the Seljuq Empire and then the Abbasid Caliphate. He was the son of Nizam al-Mulk, one of the most famous viziers ...

, the son of the first Assassin victim. The mission had some successes, negotiating a surrender of Khalinjan with local Assassin leader Ahmad ibn 'Abd al-Malik ibn Attāsh, with the occupants allowed to go to Tabas and Arrajan. But ibn Nizam al-Mulk was unable to take Alamut Castle and avenge the deaths of his father and brother Fakhr al-Mulk. During the siege of Alamut,Wasserman, p. 102 a famine resulted and Hassan had his wife and daughters sent to the fortress at Gerdkuh. After that time, Assassins never allowed their women to be at their fortresses during military campaigns, both for protection and secrecy. In the end, ibn Attāsh did not fulfill his commitment and was flayed alive, his head delivered to the sultan.

In Syria, Abu Tahir al-Sa’igh, Ridwan and Abu'l Fath of Sarmin conspired in 1106 to send a team of Assassins to murder Khalaf ibn Mula'ib, emir of Apamea (Qalaat al-Madiq

Qalaat al-Madiq ( ar, قلعة المضيق also spelled Kal'at al-Mudik or Qal'at al-Mudiq; also known as Afamiyya or Famiyyah) is a town and medieval fortress in northwestern Syria, administratively part of the Hama Governorate, located north ...

). Some of Khalaf's sons and guards were also killed and, after the murder, Ridwan became overlord of Apamea and its fortress Qal'at al-Madiq, with Abu'l Fath as emir. A surviving son of Khalaf escaped and turned to Tancred

Tancred or Tankred is a masculine given name of Germanic origin that comes from ''thank-'' (thought) and ''-rath'' (counsel), meaning "well-thought advice". It was used in the High Middle Ages mainly by the Normans (see French Tancrède) and espec ...

, who was at first content to leave the city in the hands of the Isma'ilis and simply collect tribute. Later, he returned and captured the city for Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, as the town's residents overwhelmingly approved of Frankish rule. Abu'l Fath was tortured to death, while Abu Tahir ransomed himself and returned to Aleppo. This encounter, the first between the Crusaders and the Assassins, did not deter the latter from their prime mission against the Seljuks.

Some time later, after 1108, Ahmad ibn Nizam al-Mulk himself was attacked by Assassins for revenge but survived. Not so lucky were Ubayd Allah al-Khatib, ''qadi'' of Isfahan, and a ''qadi'' of Nishapur

Nishapur or officially Romanized as Neyshabur ( fa, ;Or also "نیشاپور" which is closer to its original and historic meaning though it is less commonly used by modern native Persian speakers. In Persian poetry, the name of this city is w ...

, both of whom succumbed to the Assassins' blade.

The Assassins wreaked havoc on the Syrian rulers, with their first major kill being that of Mawdud, atabeg of Mosul, in 1113. Mawdud was felled by Assassins in Damascus while a guest of Toghtekin, atabeg of Damascus. He was replaced at Mosul by al-Bursuqi, who himself would be a victim of the Assassins in 1126. Toghtekin's son, the great Buri, founder of the Burid dynasty

The Burid dynasty was a dynasty of Turkish origin ''Burids'', R. LeTourneau, The Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. I, ed. H.A.R. Gibb, J.H. Kramers, É. Lévi-Provençal and J. Schacht, (Brill, 1986), 1332. which ruled over the Emirate of Damascus ...

, would fall victim to the Assassins in 1131, dying a year later due to his injuries.

Ridwan died in 1113 and was succeeded as ruler of Aleppo by his son Alp Arslan al-Akhras. Alp Arslan continued his father's conciliatory approach to the Assassins. A warning from Muhammad I Tapar and a prior attempt of the assassination of Abu Harb Isa ibn Zayd, a wealthy Persian merchant, led to a wholescale expulsion of the Assassins from Aleppo in that same year. Led by militia commander Sāʿid ibn Badī, the attack resulted in the execution of Abu Tahir al-Sa’igh and the brother of al-Hakim al-Munajjim, with 200 other Assassins killed or imprisoned, some thrown from the top of the citadel. Many took refuge with the Banu Munqidh at Shaizar. Revenge was slow but sure, taken out on Sāʿid ibn Badī in 1119. The shiftless Arp Arslan had exiled Sāʿid to Qalʿat Jaʿbar, where he was murdered along with two of his sons by Assassins.

The Assassins struck again in Damascus in 1116. While a guest of Toghtekin's, Kurdish emir Ahmad-Il ibn Ibrāhim ibn Wahsūdān was sitting next to his host when a grieving man approached with a petition he wished be conveyed to Muhammad I Tapar. When Ahmad-Il accepted the document, he was stuck with a dagger, then again and again by a second and third accomplice. It was thought that the real target may have Toghtekin, but the attackers were discovered to be Assassins, likely after Ahmad-Il, the foster brother of sultan.

In 1118, Muhammad I Tapar died and his brother Ahmad Sanjar became Seljuk sultan, and Hassan sent ambassadors to seek peace. When Sanjar rebuffed these ambassadors, Hassan then sent his Assassins to the sultan. Sanjar woke up one morning with a dagger stuck in the ground beside his bed. Alarmed, he kept the matter a secret. A messenger from Hassan arrived and stated, "Did I not wish the sultan well that the dagger which was struck in the hard ground would have been planted on your soft breast". For the next several decades there ensued a ceasefire between the Isma'ilis and the Seljuks. Sanjar himself pensioned the Assassins on taxes collected from the lands they owned, gave them grants and licenses, and even allowed them to collect tolls from travelers.

By 1120, the Assassins position in Aleppo had improved to the point that they demanded the small citadel of Qal'at ash-Sharif from Ilghazi, then Artuqid emir of Aleppo. Rather than refuse, he had the citadel demolished. The end of Assassin influence in Aleppo ended in 1124 when they were expelled by Belek Ghazi, a successor to Ilghazi. Nevertheless, the ''qadi'' ibn al-Khashahab who had overseen the demolition of Qal'at ash-Sharif was killed by Assassins in 1125. At the same time, the Assassins of Diyarbakir were set upon by the locals, resulting in hundreds killed.

No one was more responsible for the succession crisis that caused the exile of Nizar ibn Mustarstir than the powerful Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah. In 1121, al-Afdal was murdered by three Assassins from Aleppo, causing a seven-day celebration among the Isma'ilis and no great mourning among the court of Fatimid caliph al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah who resented his growing boldness. Al-Afdal Shahanshah was replaced as vizier by al-Ma'mum al-Bata'ihi who was instructed to prepare a letter of rapprochement between Cairo and Alamut. Upon learning of a plot to kill both al-Amir and al-Ma'mum, such ideas were disbanded, and severe restrictions on dealing with the Assassins were instead put in place.

The next generation

In 1124, Hassan-i Sabbah died, leaving a legacy that reverberated throughout the Middle East for centuries. He was succeeded at Alamut byKiya Buzurg Ummid

Kiyā Buzurg-Ummīd ( fa, کیا بزرگ امید; died 1138) was a ''dawah, dāʿī'' and the second ruler (''da'i'') of the Nizari Ismaili state#Rulers and Imams, Nizari Isma'ili State, ruling Alamut Castle from 1124 to 1138 CE (or 518—532 A ...

.

The appointment of a new ''da'i'' at Alamut may have led the Seljuks to believe the Assassins were in a weakened position, and Ahmad Sanjar launched an attack on them in 1126. Led by Sanjar's vizier Mu'in ad-Din Kashi, the Seljuks again struck at Quhistan and also Nishapur

Nishapur or officially Romanized as Neyshabur ( fa, ;Or also "نیشاپور" which is closer to its original and historic meaning though it is less commonly used by modern native Persian speakers. In Persian poetry, the name of this city is w ...

in the east, and at Rudbar to the north. In the east, the Seljuks had minor successes at a village near Sabzevar

Sabzevar ( fa, سبزوار ), previously known as Beyhagh (also spelled "Beihagh"; fa, بيهق), is a city and capital of Sabzevar County, in Razavi Khorasan Province, approximately west of the provincial capital Mashhad, in northeastern ...

, where the population was destroyed, their leader leaping from the mosque's minaret, and at Turaythirth in Nishapur, where the attackers "killed many, took much booty, and then returned." At best, the results were not decisive, but superior to the routing the Seljuks received in the north, with one expedition driven back, losing their previous booty, and another having a Seljuk commander captured. In the end, the Isma'ili position was better than before the offensive. In the guise of a peace offering of two Arabian horses, Assassins gained the confidence of Mu'in ad-Din Kashi and killed him in 1127.

At the same time, in Syria, a Persian named Bahram al-Da'i, the successor to Abu Tahir al-Sa’igh who had been executed in Aleppo in 1113, appeared in Damascus reflecting cooperation between the Assassins and Toghtekin, including a joint operation against the Crusaders. Bahram, a Persian from Asterabad (present-day Gorgan

Gorgan ( fa, گرگان ; also romanized as ''Gorgān'', ''Gurgān'', and ''Gurgan''), formerly Esterabad ( ; also romanized as ''Astarābād'', ''Asterabad'', and ''Esterābād''), is the capital city of Golestan Province, Iran. It lies appro ...

), had lived in secrecy after the expulsion of the Assassins from Aleppo and was the nephew of an Assassin Abu Ibrahim al-Asterbadi who had been executed by Barkiyaruq in 1101. Bahram was most likely behind the murder of al-Bursuqi in 1126, whose assassination may have been ordered by the Seljuk sultan Mahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, محمود ثانى, Maḥmûd-u s̠ânî, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

. He later established a stronghold near Banias

Banias or Banyas ( ar, بانياس الحولة; he, בניאס, label=Modern Hebrew; Judeo-Aramaic, Medieval Hebrew: פמייס, etc.; grc, Πανεάς) is a site in the Golan Heights near a natural spring, once associated with the Gree ...

. During an attack on the Lebanese valley of Wadi al-Taym, Bahram captured and tortured to death a local chieftain named Baraq ibn Jandal. In retaliation, his brother Dahhak ibn Jandal killed Bahram in 1127. So great was the fear and hatred of the Assassins that the messenger delivering Bahram's head and hands to Cairo was rewarded with a robe of honor. That fear was justified as caliph al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah was murdered at court in 1130 by ten Assassins.

The Isma'ili response to the Seljuk invasion of 1126 was multi-faceted. In Rudbar, a new and powerful fortress was built at Maymundiz and new territories acquired. To the east, the Seljuk stronghold of Sistan

Sistān ( fa, سیستان), known in ancient times as Sakastān ( fa, سَكاستان, "the land of the Saka"), is a historical and geographical region in present-day Eastern Iran ( Sistan and Baluchestan Province) and Southern Afghanistan ...

was raided in 1129. That same year, Mahmud II, son of Muhammad I Tapar, and sultan of Isfahan, decided to sue for peace with Alamut. Unfortunately, the Isma'ili envoys to Mahmud II were lynched by an angry mob following their audience with the sultan. The demand by Kiya Buzurg Ummid for punishment of the perpetrators was refused. That prompted an Assassin attack on Qazvin

Qazvin (; fa, قزوین, , also Romanized as ''Qazvīn'', ''Qazwin'', ''Kazvin'', ''Kasvin'', ''Caspin'', ''Casbin'', ''Casbeen'', or ''Ghazvin'') is the largest city and capital of the Province of Qazvin in Iran. Qazvin was a capital of the ...

, resulting in the loss of 400 lives in addition to a Turkish emir. A counterattack on Alamut was inconclusive.

In Syria, Assassin leader Bahram was replaced by another mysterious Persian named Isma'il al-'Ajami who, like Bahram, was supported by al-Mazdaghani, the pro-Isma'ili vizier to Toghtekin. After the death of Toghtekin in 1128, his son and successor Taj a-Mulk Buri began to free Damascus of Assassins. Supported by his military commander Yusuf ibn Firuz, al-Mazdaghani was murdered and his head publicly displayed. The Damascenes turned on the Assassins leaving "dogs yelping and quarreling over their limbs and corpses." At least 6000 Assassins died, and the rest, including Isma'il (who had turned Banias over to the Franks), fled to Frankish territory. Isma'il was killed in 1130, temporarily disabling the Assassins' Syrian mission. Nevertheless, Alamut organized a counterstrike, with two Persian Assassins disguised as Turkish soldiers who struck down Buri in 1131. The Assassins were hacked to pieces by Buri's guards, and he died of his wounds the following year.

Mahmud II died in 1131 and his brother Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud

Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud ( 1108 – 13 September 1152) was the Seljuq Sultan of Iraq and western Persia in 1133–1152.

Reign

Ghiyath ad-Din Masud was the son of sultan Muhammad I Tapar, and his wife Nistandar Jahan Khatun. At the age of twelve ( ...

(Mas'ud) was recognized as successor by Abbasid caliph al-Mustarshid

Abu Mansur al-Faḍl ibn Ahmad al-Mustazhir ( ar, أبو منصور الفضل بن أحمد المستظهر; 1092 – 29 August 1135) better known by his regnal name Al-Mustarshid Billah ( ar, المسترشد بالله) was the Abbasid calip ...

. The succession was contested by Mahmud's son and other brothers, and al-Mustarshid was draw into the conflict. The caliph al-Mustarshid was taken prisoner by Seljuk forces in 1135 near Hamadan

Hamadan () or Hamedan ( fa, همدان, ''Hamedān'') (Old Persian: Haŋgmetana, Ecbatana) is the capital city of Hamadan Province of Iran. At the 2019 census, its population was 783,300 in 230,775 families. The majority of people living in Ham ...

and pardoned with the proviso that he abdicate. Left in his tent studying the Quran, he was murdered by a large group of Assassins. Some suspected Mas'ud and even Ahmad Sanjar with complicity, but the chronicles of contemporaneous Arab historians ibn al-Athir and ibn al-Jawzi do not bear that out. The Isma'ilis commemorated the caliph's death with seven days and nights of celebration.

The reign of Buzurg Ummid ended with his death in 1138, showing a relatively small list of assassinations. He was succeeded by his son Muhammad Buzurg Ummid, sometimes referred to as Kiya Muhammad.

The Abbasids' celebration of the death of the Assassin leader Buzurg Ummid was short-lived. The son and successor of the last high-profile victim of the Assassins, al-Mustarshid, was ar-Rashid. Ar-Rashid was deposed by his uncle al-Muqtafi

Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Mustazhir ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد بن أحمد المستظهر; 9 April 1096 – 12 March 1160), better known by his regnal name al-Muqtafi li-Amr Allah (), was the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad f ...

in 1136 and, while recovering from an illness in Isfahan, was murdered by Assassins. The addition of a second caliph to the Assassins' so-called "role of honor" of victims again resulted in a week of celebration at Alamut. Another significant success was the assassination of the son of Mahmud II, Da'ud, who ruled in Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

and Jibal

Jibāl ( ar, جبال), also al-Jabal ( ar, الجبل), was the name given by the Arabs to a region and province located in western Iran, under the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates.

Its name means "the Mountains", being the plural of ''jabal'' ...

. Da'ud was felled by four Assassins in Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quru River valley in Iran's historic Azerbaijan region between long ridges of vo ...

in 1143, rumored to have been dispatched by Zengi

Zangi or Zengi may refer to:

People

* Imad al-Din Zengi (1085–1146), Turkish noble

** Zengid dynasty, a Muslim dynasty of Oghuz Turkic origin

** Nur ad-Din (died 1174) (Nūr al-Dīn Maḥmūd Zengī), his second son

* Mohammad Shammaa Al Zeng ...

, atabeg of Mosul.

The decades after the assassination of al-Mustarshid showed an expansion of Assassin castles in Jabal Bahrā', to the northwest of their Syrian fortresses in Jabal as-Summaq. In 1132, Saif al-Mulk ibn Amrun, emir of al-Kahf, recovered the fortress of al-Qadmus from the Franks, known to them as ''Bokabeis.'' He then sold the fortress to the Assassins in 1133. This was followed by the ceding of al-Kahf Castle itself to Assassin control in 1138 by Saif's son Musa in the midst of a succession struggle. These were followed by the acquisition of the castle at Masyaf in 1140 and of Qala'at al-Khawabi, known to the Crusaders as ''La Coible'', in 1141.

Relatively little is recorded concerning Assassin activity during this period until the Second Crusade

The Second Crusade (1145–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crus ...

. In 1149, an Assassin named Ali ibn-Wafa allied with Raymond of Poitiers

Raymond of Poitiers (c. 1105–29 June 1149) was Prince of Antioch from 1136 to 1149. He was the younger son of William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, and his wife Philippa, Countess of Toulouse, born in the very year that his father the Duke began hi ...

, son of William IX of Aquitaine

William IX ( oc, Guilhèm de Peitieus; ''Guilhem de Poitou'' french: Guillaume de Poitiers) (22 October 1071 – 10 February 1126), called the Troubadour, was the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and Count of Poitou (as William VII) between 1086 an ...

, to defend the borders of the Principality of Antioch against Zengid expansion. The forces met at the battle of Inab

The Battle of Inab, also called Battle of Ard al-Hâtim or Fons Muratus, was fought on 29 June 1149, during the Second Crusade. The Zengid army of Atabeg Nur ad-Din Zangi destroyed the combined army of Prince Raymond of Poitiers and the Assass ...

, with Zengi's son and heir Nur ad-Din defeating the Franks, killing both Raymond and ibn-Wafa. Nur ad-Din would again foil the Assassins in 1158, incorporating a castle at Shaizar that they had occupied after the 1157 earthquake into his territory. Two assassinations are known from this period. In a revenge attack, Dahhak ibn Jandal, the Wadi al-Taym chieftain who had killed Assassin ''da'i'' Bahram in 1127, died from an Assassin's blade in 1149. A few years later in 1152, possibly in retaliation to the establishment of the Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon ( la, Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Salomonici), also known as the Order of Solomon's Temple, the Knights Templar, or simply the Templars, was a Catholic military order, o ...

at Tartus

)

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, imagesize =

, image_caption = Tartus corniche Port of Tartus • Tartus beach and boulevard Cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa • Al-Assad Stadium& ...

, Raymond II, count of Tripoli, was killed by Assassins. This marked the first known Christian victim.

Hassan II and Rashid ad-Din Sinan

The fourteen known assassinations during the reign of Kiya Muhammad was a far cry from the tally of his predecessors, representing a significant decline in the power of the Isma'ilis. This was exemplified by the governors of Mazandaran and of Rayy who were said to have built towers out of Isma'ili skulls. That was to change with the ascension in 1162 of Ḥasan ʿAlā Zikrihi's Salām, known as Hassan II, the first to be recognized asImam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, se ...

.

In the middle of Ramadan in 559 AH, Hassan II gathered his followers and announced to "jinn

Jinn ( ar, , ') – also romanized as djinn or anglicized as genies (with the broader meaning of spirit or demon, depending on sources)

– are invisible creatures in early pre-Islamic Arabian religious systems and later in Islamic my ...

, men and angels" that the Hidden Imam had freed them "from the burden of the rules of Holy Law". With that, the assembled took part in a ritual violation of Sharia, a banquet with wine, in violation of the Ramadan fast, with their backs turned towards Medina. Observance of Islamic rites (fasting, salat prayer, etc.) was punishable by the utmost severity. (According to Shīʿa hadiths, when the Hidden Imam/mahdi reappears, "he will bring a new religion, a new book and a new law").

Resistance was nonetheless deep, and Hasan was stabbed to death by his own brother-in-law. Filiu, ''Apocalypse in Islam '', 2011: p.53

Hassan II shifted the focus of his followers from the exoteric to the esoteric ( batin). He traced his genealogy to the Fatimid Imams and Imam Nizar, which the da'is of Alamut confirmed as they were the ones in contact with the Imam. He abrogated the exoteric practice of Sharia and stressed on the esoteric ( batini) side of the laws. And "while outwardly he was known as the grandson of Buzurgumid", in this esoteric reality, Lewis writes, Hasan claimed "he was the Imam of the time

Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Mahdī ( ar, محمد بن الحسن المهدي) is believed by the Twelver Shia to be the last of the Twelve Imams and the eschatological Mahdi, who will emerge in the end of time to establish peace and justic ...

" (the last Imam of Shia Islam before the end of the world). The impact of these changes on Isma'ili life and politics were vast and continued after Hassan II's death in 1166 by his son Nūr al-Dīn Muhammad, known as the Imam Muhammad II, who ruled from 1166 to 1210. It is in this context and the changes in the Muslim world brought about by the disintegration of the Seljuk empire that a new chief ''da'i'' of the Assassins was thrust: Rashid ad-Din Sinan, referred to as Sinān

Rashid ad-Din Sinan, an alchemist and schoolmaster, was dispatched to Syria by Hassan II as a messenger of his Islamic views and to continue the Assassins' mission. Known as the greatest of the Assassin chiefs, Sinān first made headquarters at al-Kahf Castle and then the fortress of Masyaf. At al-Kahf, he worked with chief ''da'i'' Abu-Muhammad who was succeeded at his death by Khwaja Ali ibn Mas'ud without authority from Alamut. Khwaja was murdered by Abu-Muhammad's nephew Abu Mansur, causing Alamut to reassert control. After seven years at al-Kahf, Sinān assumed that role'','' operating independently of and feared by Alamut, relocating the capital to Masyaf. Among his first tasks were the refurbishing of the fortress of ar-Rusafa and of Qala'at al-Khawabi, constructing a tower at the citadel of the latter. Sinān also captured the castle of al-'Ullaiqah at Aleika, near Tartus.

One of the first orders of business that Sinān confronted was the continuing threat from Nur ad-Din as well as the Knights Templar's presence at Tartus. In 1173, Sinān proposed to Amalric of Jerusalem an alliance against Nur ad-Din in exchange for cancellation of the tribute imposed upon Assassin villages near Tartus. The Assassin envoys to the king were ambushed and slain returning from their negotiations near Tripoli by a Templar knight named Walter du Mesnil, an act apparently sanctioned by the Grand Master Odo de Saint Amand. Amalric demanded the knight be surrendered, but Odo refused, claiming only the pope had the authority to punish du Mesnil. Amalric had du Mesnil kidnapped and imprisoned at Tyre. Sinān accepted the king's apology, assured that justice had been done. The point of the alliance became moot as both Nur ad-Din and Amalric died of natural causes soon thereafter.

These developments could not have been better for Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

who wished to expand beyond Egypt into Jerusalem and Syria, first taking Damascus. With the Kingdom of Jerusalem being led by the 13-year old leperous Baldwin IV and Syria by the 11-year old as-Salih Ismail al-Malik, son of Nur ad-Din, he continued his campaign in Syria, moving against Aleppo. While besieging Aleppo in late 1174 or early 1175, the camp of Saladin was infiltrated by Assassins sent by Sinān and As-Salih's regent Gümüshtigin. Nasih al-Din Khumartekin, emir of Abu Qubays Abu Qubays may refer to the following places:

* Abu Qubays (mountain), a mountain near Mecca, Saudi Arabia

*Abu Qubays, Syria

Abu Qubays ( ar, أبو قبيس also spelled ''Abu Qobeis'', ''Abu Qubais'' or ''Bu Kubais''; also known as Qartal) is ...

, was killed in the attack which left Saladin unscathed. The next year, after taking Azaz, Assassins again struck, wounding Saladin. Gümüshtigin was again believed to be complicit in the assassination attempt. Turning his attention to Aleppo, the city was soon conquered and Saladin allowed as-Salih and Gümüshtigin to continue to rule, but under his sovereignty. Saladin then turned his attention back to the Assassins, besieging Masyaf in 1176. Failing to capture the stronghold, he settled for a truce. Accounts of a mystical encounter between Saladin and Sinān have been offered :

Saladin had his guards supplied with link lights and had chalk and cinders strewed around his tent outside Masyaf—which he was besieging—to detect any footsteps by the Assassins. According to this version, one night Saladin's guards noticed a spark glowing down the hill of Masyaf and then vanishing among the Ayyubid tents. Presently, Saladin awoke to find a figure leaving the tent. He saw that the lamps were displaced and beside his bed laid hot scones of the shape peculiar to the Assassins with a note at the top pinned by a poisoned dagger. The note threatened that he would be killed if he did not withdraw from his assault. Saladin gave a loud cry, exclaiming that Sinan himself was the figure that had left the tent.

Another version claims that Saladin hastily withdrew his troops from Masyaf because they were urgently needed to fend off a Crusader force in the vicinity of Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

. In reality, Saladin sought to form an alliance with Sinan and his Assassins, consequently depriving the Crusaders of a potent ally against him. Viewing the expulsion of the Crusaders as a mutual benefit and priority, Saladin and Sinan maintained cooperative relations afterwards, the latter dispatching contingents of his forces to bolster Saladin's army in a number of decisive subsequent battlefronts.

By 1177, The conflict between Sinān and as-Salih continued with the assassination of Shihab ad-Din abu-Salih, vizier to both as-Salih and Nur ad-Din. A letter from as-Salih to Sinān requesting the murder was found to be a forgery by Gümüshtigin, causing his removal. As-Salih seized the village of al-Hajira from the Assassins, and in response Sinān's followers burned the marketplace in Aleppo.

In 1190, Isabella I was Queen of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

had just begun. The daughter of Amalric, she married her first husband Conrad of Montferrat

Conrad of Montferrat ( Italian: ''Corrado del Monferrato''; Piedmontese: ''Conrà ëd Monfrà'') (died 28 April 1192) was a nobleman, one of the major participants in the Third Crusade. He was the ''de facto'' King of Jerusalem (as Conrad I) by ...

, who became king by virtue of marriage, not yet crowned. Conrad was of royal blood, the cousin of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt ...

and Louis VII of France

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

. Conrad had been in charge of Tyre during the siege of Tyre in 1187 launched by Saladin, successfully defending the city. Guy of Lusignan

Guy of Lusignan (c. 1150 – 18 July 1194) was a French Poitevin knight, son of Hugh VIII of Lusignan and as such born of the House of Lusignan. He was king of Jerusalem from 1186 to 1192 by right of marriage to Sibylla of Jerusalem, and Kin ...

, married to Isabella's half-sister Sybilla of Jerusalem Sibylla is a female given name. It may refer to:

* Sibylla of Jerusalem (c. 1160–1190), queen regnant of Jerusalem

* Sybilla of Normandy (c. 1092–1122), queen consort of Scotland

* Sibylla of Acerra (1153–1205), queen consort of Sicily

* Siby ...

, was king of Jerusalem by right of marriage and had been captured by Saladin during the battle of Hattin in that same year, 1187. When Guy was released in 1188, he was denied entry to Tyre by Conrad and launched the siege of Acre in 1189. Queen Sybilla died of an epidemic sweeping her husband's military camp in 1190, negating Guy's claim to the throne and resulting in Isabella becoming queen.

Assassins disguised as Christian monks had infiltrated the bishopric of Tyre, gaining the confidence of both the archbishop Joscius and Conrad of Montferrat. There in 1192, they stabbed Conrad to death. The surviving Assassin is reputed to have named Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and Duchy of Gascony, Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Co ...

as the instigator, who had much to gain as demonstrated by the rapidity at which the widow married Henry II of Champagne. That account is disputed by ibn al-Athir who names Saladin in a plot with Sinān to kill both Conrad and Richard. Richard I was captured by Leopold V, Duke of Austria

Leopold V (1157 – 31 December 1194), known as the Virtuous (german: der Tugendhafte) was a member of the House of Babenberg who reigned as Duke of Austria from 1177 and Duke of Styria from 1192 until his death. The Georgenberg Pact resulted ...

, and held by Henry VI, who had become Holy Roman Emperor in 1191, accused of murder. Sinān wrote to Leopold V absolving Richard I of complicity in the plot. Regardless, Richard I was released in 1194 after England paid his ransom and the murder remains unsolved. Adding to the continued cold case is the belief by modern historians that Sinan's letter to Leopold V is a forgery, written by members of Richard I's administration.

Conrad was Sinān's last assassination. The great Assassin Rashid ad-Din Sinan, the Old Man of the Mountain, died in 1193, the same year that claimed Saladin. He died of natural causes at al-Kahf Castle and was buried at Salamiyah

A full view of Shmemis (spring 1995)

Salamieh ( ar, سلمية ') is a city and district in western Syria, in the Hama Governorate. It is located southeast of Hama, northeast of Homs. The city is nicknamed the "mother of Cairo" because it was ...

, which had been a secret hub of Isma'ili activity in the 9th and 10th centuries. His successor was Nasr al-'Ajami, under the control of Alamut, who reportedly met with emperor Henry VI in 1194. Later successors through 1227 included Kamāl ad-Din al-Hasan and Majd ad-Din, again under the control of Alamut. Saladin left his Ayyubid dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladi ...

under his sons al-Aziz Uthman, sultan of Egypt, al-Afdal ibn Salah ad-Din, emir of Damascus, and az-Zahir Ghazi, emir of Aleppo. Al-Aziz died soon thereafter, replaced by Saladin's brother al-Adil I

Al-Adil I ( ar, العادل, in full al-Malik al-Adil Sayf ad-Din Abu-Bakr Ahmed ibn Najm ad-Din Ayyub, ar, الملك العادل سيف الدين أبو بكر بن أيوب, "Ahmed, son of Najm ad-Din Ayyub, father of Bakr, the Just K ...

.

13th century

In 1210, Muhammad III died and his son Jalāl al-Din Hasan (known as Hassan III) became Imam of the Nizari Isma'ili State. His first actions included the return to the Islamic orthodoxy by practisingTaqiyyah

In Shi'ism, ''Taqiya'' or ''Taqiyya'' ( ar, تقیة ', literally "prudence, fear")R. STROTHMANN, MOKTAR DJEBLI. Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed, Brill. "TAKIYYA", vol. 10, p. 134. Quote: "TAKIYYA "prudence, fear" ..denotes dispensing with th ...

to ensure safety of the Ismailis in the hostile environment. He claimed allegiance to the Sunnis

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word ''Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagree ...

to protect himself and his followers from further persecution. He had a Sunni mother and four Sunni wives. Hassan III recognized the Abbasid caliph al-Nasir who in turn granted a diploma of investiture. The Alamuts had a previous history with al-Nasir, supplying Assassins to attack a Kwarezm representative of shah Ala ad-Din Tekish, but that was more of an action of convenience than formal alliance. Maintaining ties to western Christian influences, the Alamuts became tributaries to the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

beginning at the Isma'ili stronghold Abu Qubays Abu Qubays may refer to the following places:

* Abu Qubays (mountain), a mountain near Mecca, Saudi Arabia

*Abu Qubays, Syria

Abu Qubays ( ar, أبو قبيس also spelled ''Abu Qobeis'', ''Abu Qubais'' or ''Bu Kubais''; also known as Qartal) is ...

, near Margat.

The count of Tripoli in 1213 was Bohemond IV, the fourth prince of Antioch of that name. That year his 18-year-old son Raymond, namesake of his grandfather, was murdered by the Assassins under Nasr al-'Ajami while at church in Tartus

)

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, imagesize =

, image_caption = Tartus corniche Port of Tartus • Tartus beach and boulevard Cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa • Al-Assad Stadium& ...

. Suspecting both Assassin and Hospitaller involvement, Bohemond and the Knights Templar laid siege to Qala'at al-Khawabi, an Isma'ili stronghold near Tartus, Appealing to the Ayyubids for help, az-Zahir Ghazi dispatched a relief force from Aleppo. His forces were nearly destroyed at Jabal Bahra. Az-Zahir's uncle al-Adil I, emir of Damascus, responded and the Franks ended the siege by 1216. Bohemond IV would again fight the Ayyudibs in the Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign in a series of Crusades by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by al-Adil, brother of Sala ...

.

Majd ad-Din was the new chief ''da'i'' in Syria in 1220, assuming that role from Kamāl ad-Din al-Hasan of whom very little is known. At that time the Seljuk sultanate of Rûm

fa, سلجوقیان روم ()

, status =

, government_type = Hereditary monarchy Triarchy (1249–1254)Diarchy (1257–1262)

, year_start = 1077

, year_end = 1308

, p1 = B ...

paid an annual tribute to Alamut, and Majd ad-Din notified the sultan Kayqubad I

Alā ad-Dīn Kayqubād ibn Kaykhusraw ( fa, علاء الدين كيقباد بن كيخسرو; tr, I. Alâeddin Keykûbad, 1190–1237), also known as Kayqubad I, was the Seljuq Sultan of Rûm who reigned from 1220 to 1237. He expanded th ...

that henceforth the tribute was to be paid to him. Kayqubad I requested clarification from Hassan III who informed him that the monies had indeed been assigned to Syria.Lewis (2003), pg. 120

Hassan III died in 1221, likely from poisoning. He was succeeded by his 9-year-old son Imam 'Alā ad-Din Muhammad, known as Muhammad III, and was the penultimate Isma'ili ruler of Alamut before the Mongol conquest. Because of his age, Hassan's vizier served as regent to the young Imam, and put Hassan's wives and sister to death for the suspected poisoning. Muhammad III reversed the Sunni course his father had set, returning to Shi'ite orthodoxy. His attempts to accommodate the advancing Mongols failed.

In 1225, Frederick II was Holy Roman Emperor, a position his father Henry VI had held until 1197. He had committed to prosecuting the Sixth Crusade

The Sixth Crusade (1228–1229), also known as the Crusade of Frederick II, was a military expedition to recapture Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land. It began seven years after the failure of the Fifth Crusade and involved very little actu ...

and married the heiress to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Isabella II. The next year, the once and future king sent envoys to Majd ad-Din with significant gifts for the imam to ensure his safe passage. Khwarezm

Khwarazm (; Old Persian: ''Hwârazmiya''; fa, خوارزم, ''Xwârazm'' or ''Xârazm'') or Chorasmia () is a large oasis region on the Amu Darya river delta in western Central Asia, bordered on the north by the (former) Aral Sea, on the ...

had collapsed under the Mongols, but many of the Kwarezmians still operated as mercenaries in northern Iraq. Under the pretense that the road to Alamut was unsafe due to these mercenaries, Majd ad-Din kept the gifts for himself, and provided the safe passage. As a precaution, Majd ad-Din informed al-Aziz Muhammad, emir of Aleppo and son of az-Zahir Ghazi, of the emperor's embassy. In the end, Frederick did not complete that trip to the Holy Land due to illness, being excommunicated in 1227. The Knights Hospitaller were not as accommodating as Alamut, demanding their share of the tribute. When Majd ad-Din refused, the Hospitallers attacked and carried off the majority of the booty. Majd ad-Din was succeeded by Sirāj ad-Din Muzaffa ibn al-Husain in 1227, serving as chief ''da'i'' until 1239.

Taj ad-Din Abu'l-Futūh ibn Muhammad was chief ''da'i'' in Syria in 1239, succeeding Sirāj ad-Din Muzaffa. At this point, the Assassins were an integral part of Syrian politics. The Arab historian Ibn Wasil had a friendship with Taj ad-Din and writes of Badr ad-Din, ''qadi'' of Sinjar, who sought refuge with Taj ad-Din to escape the wrath of Egyptian Ayyubid ruler as-Salih Ayyub

Al-Malik as-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub (5 November 1205 – 22 November 1249), nickname: Abu al-Futuh ( ar, أبو الفتوح), also known as al-Malik al-Salih, was the Ayyubid Kurdish ruler of Egypt from 1240 to 1249.

Early life

In 1221, as- ...

. Taj ad-Din served until at least 1249 when he was replaced by Radi ad-Din Abu'l-Ma'āli.

In that same year, Louis IX of France embarked on the Seventh Crusade in Egypt. He captured the port of Damietta from the aging al-Salih Ayyub which he refused to turn over to Conrad II, who had inherited the throne of Jerusalem from his parents Frederick II and Isabella II. The Frankish Crusaders were soundly defeated by Abu Futuh Baibars, then a commander in the Egyptian army, at the battle of al-Mansurah in 1250. Saint Louis, as Louis IX was known, was captured by the Egyptians and, after a handsome reward was paid, spent four years in Acre, Caesarea and Jaffa. One of the captives with Louis was Jean de Joinville, biographer of the king, who reported the interaction of the monarch with the Assassins. While at Acre, emissaries of Radi ad-Din Abu'l-Ma'āli met with him, demanding a tribute be paid to their chief "as the emperor of Germany, the king of Hungary, the sultan of Egypt and the others because they know well they can only live as long as it please him." Alternately, the king could pay the tribute the Assassins paid the Templars and Hospitallers. Later the king's Arabic interpreter Yves the Breton met personally with Radi ad-Din and discussed the respective beliefs. Afterwards, the chief ''da'i'' went riding, with his valet proclaiming: "Make way before him who bears the death of kings in his hands!"

The Egyptian victory at al-Mansurah led to the establishment of the Mamluk dynasty in Egypt. Muhammad III was murdered in 1255 and replaced by his son Rukn al-Din Khurshah, the last Imam to rule Alamut. Najm ad-Din later became chief ''da'i'' of the Assassins in Syria, the last to be associated with Alamut. Louis IX returned to north Africa during the Eighth Crusade

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see any ...

where he died of natural causes in Tunis.

Downfall and aftermath

The Assassins suffered a significant blow at the hands of the

The Assassins suffered a significant blow at the hands of the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe ...

during the well-documented invasion of Khwarazm

Khwarazm (; Old Persian: ''Hwârazmiya''; fa, خوارزم, ''Xwârazm'' or ''Xârazm'') or Chorasmia () is a large oasis region on the Amu Darya river delta in western Central Asia, bordered on the north by the (former) Aral Sea, on the e ...

. A decree was handed over to the Mongol commander Kitbuqa

Kitbuqa Noyan (died 1260), also spelled Kitbogha, Kitboga, or Ketbugha, was an Eastern Christian of the Naimans, a group that was subservient to the Mongol Empire. He was a lieutenant and confidant of the Mongol Ilkhan Hulagu, assisting him ...

who began to assault several Assassin fortresses in 1253 before Hulagu's advance in 1256, seizing Alamut late that year. Lambsar fell in 1257, Masyaf in 1267. The Assassins recaptured and held Alamut for a few months in 1275, but they were crushed and their political power was lost forever. Rukn al-Din Khurshah was put to death shortly thereafter.Lewis (2003), pp. 121–122

Though the Mongol massacre at Alamut was widely interpreted to be the end of Isma'ili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor ( imām) to Ja'far al- ...