Harry McNish on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry McNish (11 September 187424 September 1930), often referred to as Harry McNish or by the nickname Chippy, was the carpenter on Sir

McNish, at 40, was one of the oldest members of the crew of the ''Endurance'' (Shackleton though was seven months older). He suffered from piles and

McNish, at 40, was one of the oldest members of the crew of the ''Endurance'' (Shackleton though was seven months older). He suffered from piles and

During his watch one night while the crew were camped on the ice, a small part of the

During his watch one night while the crew were camped on the ice, a small part of the

McNish used the mast of another of the boats, the ''Stancomb Wills'', to strengthen the keel and build up the small 22 foot (6.7 m) long boat, so it would withstand the seas during the 800 mile (1480 km) trip. He caulked it using a mixture of seal blood and flour, and, using wood and nails taken from packing cases and the runners of the sledges, he built a makeshift frame which was then covered with canvas. Shackleton was worried the boat "bore a strong likeness to stage scenery", only giving the appearance of sturdiness. He later admitted that the crew could not have lived through the voyage without it.

When launching the boat McNish and John Vincent were thrown from the deck into the sea. Although soaked, both were unharmed, and managed to exchange some clothes with the Elephant Island party before the ''James Caird'' set off. The mood on board was buoyant and McNish recorded in his diary on 24 April 1916:

The mood did not last though: conditions aboard the small craft during the trip were terrible, with the crew constantly soaked and cold. McNish impressed Shackleton with his ability to bear up under the strain (more so than the younger Vincent, who collapsed from exhaustion and cold). The six men split into two watches of four hours: three of the men would handle the boat while the other three lay beneath the canvas decking attempting to sleep. McNish shared a watch with Shackleton and Crean. All the men complained of pains in their legs and, on the fourth day out from Elephant Island, McNish suddenly sat down and removed his boots, revealing his legs and feet were white and puffy with the early signs of

McNish used the mast of another of the boats, the ''Stancomb Wills'', to strengthen the keel and build up the small 22 foot (6.7 m) long boat, so it would withstand the seas during the 800 mile (1480 km) trip. He caulked it using a mixture of seal blood and flour, and, using wood and nails taken from packing cases and the runners of the sledges, he built a makeshift frame which was then covered with canvas. Shackleton was worried the boat "bore a strong likeness to stage scenery", only giving the appearance of sturdiness. He later admitted that the crew could not have lived through the voyage without it.

When launching the boat McNish and John Vincent were thrown from the deck into the sea. Although soaked, both were unharmed, and managed to exchange some clothes with the Elephant Island party before the ''James Caird'' set off. The mood on board was buoyant and McNish recorded in his diary on 24 April 1916:

The mood did not last though: conditions aboard the small craft during the trip were terrible, with the crew constantly soaked and cold. McNish impressed Shackleton with his ability to bear up under the strain (more so than the younger Vincent, who collapsed from exhaustion and cold). The six men split into two watches of four hours: three of the men would handle the boat while the other three lay beneath the canvas decking attempting to sleep. McNish shared a watch with Shackleton and Crean. All the men complained of pains in their legs and, on the fourth day out from Elephant Island, McNish suddenly sat down and removed his boots, revealing his legs and feet were white and puffy with the early signs of

After the expedition McNish returned to the Merchant Navy, working on various ships. He often complained that his bones permanently ached due to the conditions during the journey in the ''James Caird''; he would reportedly sometimes refuse to shake hands because of the pain. He divorced Lizzie Littlejohn on 2 March 1918, by which time he had already met his new partner, Agnes Martindale. McNish had a son named Tom and Martindale had a daughter named Nancy. Although she is mentioned frequently in his diary, it appears McNish was not Nancy's father.

He spent 23 years in the Navy in total during his life, but eventually secured a job with the New Zealand Shipping Company. After making five trips to New Zealand he moved there in 1925, leaving behind his wife and all of his carpentry tools. He worked on the waterfront in

After the expedition McNish returned to the Merchant Navy, working on various ships. He often complained that his bones permanently ached due to the conditions during the journey in the ''James Caird''; he would reportedly sometimes refuse to shake hands because of the pain. He divorced Lizzie Littlejohn on 2 March 1918, by which time he had already met his new partner, Agnes Martindale. McNish had a son named Tom and Martindale had a daughter named Nancy. Although she is mentioned frequently in his diary, it appears McNish was not Nancy's father.

He spent 23 years in the Navy in total during his life, but eventually secured a job with the New Zealand Shipping Company. After making five trips to New Zealand he moved there in 1925, leaving behind his wife and all of his carpentry tools. He worked on the waterfront in

map

b. There was little doubt as to his skill as a shipwright even before he was called upon for the modifications to the boats. He was never seen to take measurements, producing perfect work by eye. Macklin commented that all the work he did was first class, and even

Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of ...

's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing ...

of 1914–1917. He was responsible for much of the work that ensured the crew's survival after their ship, the ''Endurance

Endurance (also related to sufferance, resilience, constitution, fortitude, and hardiness) is the ability of an organism to exert itself and remain active for a long period of time, as well as its ability to resist, withstand, recover from a ...

'', was destroyed when it became trapped in pack ice in the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

. He modified the small boat, '' James Caird'', that allowed Shackleton and five men (including McNish) to make a voyage of hundreds of miles to fetch help for the rest of the crew.

After the expedition he returned to work in the Merchant Navy and eventually emigrated to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, where he worked on the docks in Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

until poor health forced his retirement. He died destitute in the Ohiro Benevolent Home in Wellington.

Early life

Harry "Chippy" McNish was born in 1874 in the former Lyons Lane near the present site of the library inPort Glasgow

Port Glasgow ( gd, Port Ghlaschu, ) is the second-largest town in the Inverclyde council area of Scotland. The population according to the 1991 census for Port Glasgow was 19,426 persons and in the 2001 census was 16,617 persons. The most recen ...

, Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire () ( sco, Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Renfr ...

, Scotland. He was part of a large family, being the third of eleven children born to John and Mary Jane (née Wade) McNish. His father was a journeyman

A journeyman, journeywoman, or journeyperson is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that fie ...

shoemaker

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or cobblers (also known as '' cordwainers''). In the 18th century, dozens or even hundreds of masters, journeymen ...

. McNish held strong socialist views, was a member of the United Free Church of Scotland

The United Free Church of Scotland (UF Church; gd, An Eaglais Shaor Aonaichte, sco, The Unitit Free Kirk o Scotland) is a Scottish Presbyterian denomination formed in 1900 by the union of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (or UP) and ...

and detested bad language. He married three times: in 1895 to Jessie Smith, who died in February 1898; in 1898 to Ellen Timothy, who died in December 1904; and finally to Lizzie Littlejohn in 1907.

There is some confusion as to the correct spelling of his name. He is variously referred to as McNish, McNeish, and in Alexander Macklin

Alexander Hepburne Macklin (1889 – 21 March 1967) was a British physician who served as one of the two surgeons on Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917. In 1921–1922, he joined the Shackleton–Row ...

's diary of the expedition, MacNish. The McNeish spelling is common, notably in Shackleton's and Frank Worsley

Frank Arthur Worsley (22 February 1872 – 1 February 1943) was a New Zealand sailor and explorer who served on Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1916, as captain of ''Endurance''. He also served in the Royal N ...

's accounts of the expedition and on McNish's headstone, but McNish is also widely used, and appears to be the correct version. On a signed copy of the expedition photo his signature appears as "H. MacNish", but his spelling is in general idiosyncratic, as revealed in the diary he kept throughout the expedition. There also is a question regarding McNish's nickname. "Chippy" was a traditional nickname for a shipwright

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

; both this and the shorter "Chips" (as in wood chips from carpentry) seem to have been used.

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

''Endurance''

The aim of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was to be the first to cross theAntarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and other ...

continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

from one side to the other. McNish was apparently attracted by Shackleton's advertisement for the expedition (although there are doubts as to whether the advertisement ever appeared):

McNish, at 40, was one of the oldest members of the crew of the ''Endurance'' (Shackleton though was seven months older). He suffered from piles and

McNish, at 40, was one of the oldest members of the crew of the ''Endurance'' (Shackleton though was seven months older). He suffered from piles and rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including art ...

in his legs. He was regarded as somewhat odd and unrefined, but also highly respected as a carpenterFrank Worsley

Frank Arthur Worsley (22 February 1872 – 1 February 1943) was a New Zealand sailor and explorer who served on Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1916, as captain of ''Endurance''. He also served in the Royal N ...

, the captain of the ''Endurance'', refers to him as a "splendid shipwright". The pipe-smoking Scot was, however, the only man of the crew that Shackleton was "not dead certain of". His Scots accent was described as rasping like "frayed cable wire".

During the initial stage of the voyage to Antarctica from Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, he was kept busy with a number of routine tasks. He worked on the pram dinghy ''Nancy Endurance''; made a small chest of drawers for Shackleton; specimen shelves for the biologist, Robert Clark Robert, Bob, or Bobby Clark may refer to:

Television and film

*Robert Clark (actor) (born 1987), American-born Canadian television actor

*Bob Clark (1939–2007), Canadian filmmaker

*Bob Clark (television reporter), retired American television rep ...

; and instrument cases for Leonard Hussey

Leonard Duncan Albert Hussey, Officer of the Order of the British Empire, OBE (6 May 1891 – 25 February 1964) was an English meteorologist, archaeologist, explorer, medical doctor and member of Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expe ...

, the meteorologist; and put up wind screens to protect the helmsman. He constructed a false deck, extending from the poop-deck to the chart-room to cover the extra coal that the ship had taken on board. He also acted as the ship's barber. As the ship pushed into the pack ice in the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

it became increasingly difficult to navigate. McNish constructed a six-foot wooden semaphore on the bridge to enable the navigating officer to give the helmsman directions, and built a small stage over the stern to allow the propeller to be watched in order to keep it clear of the heavy ice.

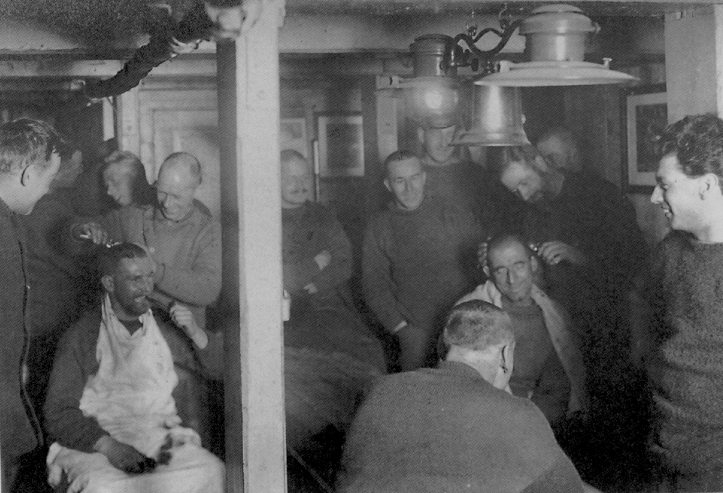

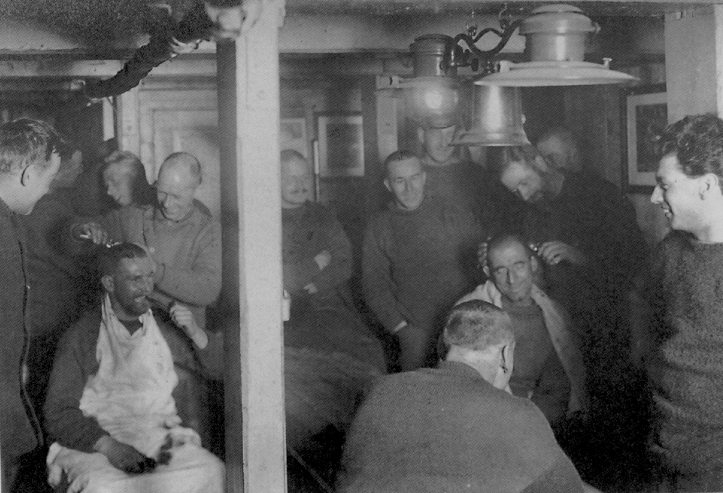

When the ship became trapped in pack ice his duties expanded to constructing makeshift housing, and, once it became clear that the ship was doomed, to altering the sledges for the journey over the ice to open water. He built the quarters where the crew took their meals (nicknamed ''The Ritz'') and cubicles where the men could sleep. These were all christened as well; McNish shared ''The Sailors' Rest'' with Alfred Cheetham

Alfred Cheetham (6 May 1866 – 22 August 1918) was a member of several Antarctic expeditions. He served as third officer for both the ''Nimrod'' expedition and Imperial Trans-Antarctic expedition.

He died at sea when his ship was torpe ...

, the Third Officer. Assisted by the crew, he constructed kennels for the dogs on the upper deck. Once ''Endurance'' became trapped, and the crew were spending the days on the ice, McNish erected goalposts and football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

became a daily fixture for the men. To pass the time in the evening, McNish joined Frank Wild

John Robert Francis Wild (18 April 1873 – 19 August 1939), known as Frank Wild, was an English sailor and explorer. He participated in five expeditions to Antarctica during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, for which he was awar ...

, Tom Crean Tom or Thomas Crean may refer to:

*Thomas Crean (1873–1923), Irish rugby union player, British Army soldier and doctor

*Tom Crean (explorer) (1877–1938), Irish seaman and Antarctic explorer

*Tom Crean (basketball)

Thomas Aaron Crean (born Ma ...

, James McIlroy, Worsley and Shackleton playing poker in the wardroom

The wardroom is the mess cabin or compartment on a warship or other military ship for commissioned naval officers above the rank of midshipman. Although the term typically applies to officers in a navy, it is also applicable to marine officers ...

.

The pressure from the ice caused ''Endurance'' to start to take on water. To prevent the ship from flooding McNish built a cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for construction or re ...

, caulking

Caulk or, less frequently, caulking is a material used to seal joints or seams against leakage in various structures and piping.

The oldest form of caulk consisted of fibrous materials driven into the wedge-shaped seams between boards on w ...

it with strips of blankets and nailing strips over the seams, standing for hours up to his waist in freezing water as he worked. He could not prevent the pressure from the ice crushing the ship though and was experienced enough to know when to stop trying. Once the ship had been destroyed he was put in charge of rescuing the stores from what had been ''The Ritz''. With McNish in charge it took only a couple of hours to open the deck far enough to retrieve a good quantity of provisions.

On the ice

During his watch one night while the crew were camped on the ice, a small part of the

During his watch one night while the crew were camped on the ice, a small part of the ice floe

An ice floe () is a large pack of floating ice often defined as a flat piece at least 20 m across at its widest point, and up to more than 10 km across. Drift ice is a floating field of sea ice composed of several ice floes. They may caus ...

broke away and he was only rescued due to the quick intervention of the men of the next watch who threw him a line allowing him to jump back to safety. Shackleton reported that McNish calmly mentioned his narrow escape the next day after further cracks appeared in the ice. Mrs Chippy

Mrs Chippy was a male ship's cat who accompanied Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917.

Life

Mrs Chippy, a tiger-striped tabby cat, tabby, was taken on board the ship used by the expedition's Weddell Sea pa ...

, the cat McNish had brought on board, had to be shot after the loss of the ''Endurance'', as it was obvious he would not survive the harsh conditions. McNish apparently never forgave Shackleton for giving the order.

McNish proposed building a smaller craft from the wreckage of the ship, but was overruled, with Shackleton instead deciding to head across the ice to open water pulling the ship's three lifeboats. McNish had been suffering with piles and homesickness from almost before the voyage had begun, and once the ship was lost his frustration began to grow. He vented his feelings in his diary, targeting his tent-mates' language:

In great pain while pulling sledges across the ice, McNish briefly rebelled, refusing to take his turn in the harness and protesting to Frank Worsley that since the ''Endurance'' had been destroyed the crew was no longer under any obligation to follow orders. Accounts vary as to how Shackleton handled this: some report that he threatened to shoot McNish; others that he read him the ship's articles, making it clear that the crew were still under obligation until they reached port. McNish's assertion would have normally been correct: duty to the master (and pay) normally stopped when a ship was lost, but the articles the crew had signed for the ''Endurance'' had a special clause inserted in which the crew agreed "to perform any duty on board, in the boats, or on the shore as directed by the master and owner". Aside from this, McNish really had no choice but to comply: he could not survive alone and could not continue with the rest of the party unless he obeyed orders.

As supplies began to dwindle the party grew hungry. McNish records that he smoked himself sick trying to alleviate the pangs of hunger and although he thought the shooting of the dogs terribly sad, he was happy to eat the meat they provided stating "Their flesh tastes a treat. It is a big treat for us after being so long on seal meat

Seal meat is the flesh, including the blubber and organs, of Pinniped, seals used as food for humans or other animals. It is prepared in numerous ways, often being hung and dried before consumption. Historically, it has been eaten in many parts of ...

."

When the ice finally brought the camp to the edge of the pack ice, Shackleton decided that the three boats, the ''James Caird'', ''Stancomb Wills'', and ''Dudley Docker'', should make initially for Elephant Island

Elephant Island is an ice-covered, mountainous island off the coast of Antarctica in the outer reaches of the South Shetland Islands, in the Southern Ocean. The island is situated north-northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, west-so ...

. McNish had prepared the boats as best he could for a long journey in the open ocean, building up their sides to give them a higher clearance from the water.

Elephant Island and the ''James Caird''

On the sea journey toElephant Island

Elephant Island is an ice-covered, mountainous island off the coast of Antarctica in the outer reaches of the South Shetland Islands, in the Southern Ocean. The island is situated north-northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, west-so ...

, McNish was in the '' James Caird'' with Shackleton and Frank Wild

John Robert Francis Wild (18 April 1873 – 19 August 1939), known as Frank Wild, was an English sailor and explorer. He participated in five expeditions to Antarctica during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, for which he was awar ...

. As they approached the island, Wild, who had been at the tiller for 24 hours straight, was close to collapse, so Shackleton ordered McNish to relieve him. McNish was not in a much better state himself and, despite the terrible conditions, he fell asleep after half an hour. The boat swung around and a huge wave drenched him. This was enough to wake him, but Shackleton, seeing McNish too was exhausted, ordered him to be relieved.

After the crew had made it to Elephant Island, Shackleton decided to take a small crew and make for South Georgia

South Georgia ( es, Isla San Pedro) is an island in the South Atlantic Ocean that is part of the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It lies around east of the Falkland Islands. Stretching in the east� ...

, where there was a possibility that they would find crews from the whaling ships to help effect a rescue for the rest of the men. McNish was called upon by Shackleton to make the ''James Caird'' seaworthy for the long voyage and was selected as part of the crew, possibly because Shackleton was afraid of the effect he would have on morale if left behind with the other men. For his part, McNish seemed happy to go; he was unimpressed by the island and the chances of survival for the men overwintering there:

trench foot

Trench foot is a type of foot damage due to moisture. Initial symptoms often include tingling or itching which can progress to numbness. The feet may become red or bluish in color. As the condition worsens the feet can start to swell and smel ...

. On seeing the state of McNish's feet Shackleton ordered all the men to remove their boots.

South Georgia

The crew of the ''James Caird'' reached South Georgia on 10 May 1916, 15 days after setting out from Elephant Island. They landed inCave Cove

King Haakon Bay, or King Haakon Sound, is an inlet on the southern coast of the island of South Georgia Island, South Georgia. The inlet is approximately 13 km (8 miles) long and 4 km (2.5 miles) wide. The inlet was named for King Haak ...

on King Haakon Bay

King Haakon Bay, or King Haakon Sound, is an inlet on the southern coast of the island of South Georgia. The inlet is approximately 13 km (8 miles) long and 4 km (2.5 miles) wide. The inlet was named for King Haakon VII of Norway by ...

; it was on the wrong side of the island, but it was a relief for all of them to make land; McNish wrote in his diary:

They found albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacifi ...

chicks and seals to eat, but despite the relative comfort of the island compared to the small boat, they still urgently needed to reach the whaling station at Husvik

Husvik is a former whaling station on the north-central coast of South Georgia Island. It was one of three such stations in Stromness Bay, the other two being Stromness and Leith Harbour. Husvik initially began as a floating, offshore factory sit ...

on the other side of the island to fetch help for the men on Elephant Island. It was clear that McNish and Vincent could not continue, so Shackleton left them in the care of Timothy McCarthy camped in the upturned ''James Caird'', and with Worsley and Crean made the hazardous trip over the mountains. McNish took screws from the ''James Caird'' and attached them to the boots of the men making the journey to help them grip the ice. He also fashioned a crude sledge from driftwood he found on the beach, but it proved too clumsy to be practical. When Shackleton's party set off on 18 May 1916, McNish accompanied them for a few hundred yards but he was unable to go any further. He shook hands with each of the men, wishing them good luck, and then Shackleton sent him back. Putting McNish in command of the remaining men, Shackleton charged him to wait for relief and if none had come by the end of winter to attempt to sail to the east coast. Once Shackleton's party had crossed the mountains and arrived in Husvik, he sent Worsley with one of the whaler's ships, ''Samson'', to pick up McNish and the other men. After seeing the emaciated and drawn McNish on his arrival at the whaling station, Shackleton recorded that he felt that the rescue had come just in time for him.

Polar Medal

Whatever the true story of the rebellion on the ice, neither Worsley nor McNish ever mentioned the incident in writing. Shackleton omitted it entirely from ''South'', his account of the expedition, and referred to it only tangentially in his diary: "Everyone working well except the carpenter. I shall never forget him in this time of strain and stress". The event was recorded in the ship's log, but the log entry was struck during the sea voyage in the ''James Caird'', Shackleton being impressed by the carpenter's show of "grit and spirit". Nevertheless, McNish's name appeared on the list of the four men not recommended for the Polar Medal in the letter sent by Shackleton on his return. Macklin thought the denial of the medal unjustified: Macklin believed that Shackleton may have been influenced in his decision by Worsley who shared a mutual enmity with McNish, and had accompanied Shackleton back from Antarctica. Members of theScott Polar Research Institute

The Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) is a centre for research into the polar regions and glaciology worldwide. It is a sub-department of the Department of Geography in the University of Cambridge, located on Lensfield Road in the south o ...

, New Zealand Antarctic Society

New Zealand Antarctic Society was formed in 1933 by New Zealand businessman Arthur Leigh Hunt and Antarctic explorers Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd and Sir Douglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson OBE FRS FAA (5 May 1882 – 14 October 1958) ...

and Caroline Alexander, the author of ''Endurance'', have criticised Shackleton's denial of the award to McNish.

Later life, memorials and records

After the expedition McNish returned to the Merchant Navy, working on various ships. He often complained that his bones permanently ached due to the conditions during the journey in the ''James Caird''; he would reportedly sometimes refuse to shake hands because of the pain. He divorced Lizzie Littlejohn on 2 March 1918, by which time he had already met his new partner, Agnes Martindale. McNish had a son named Tom and Martindale had a daughter named Nancy. Although she is mentioned frequently in his diary, it appears McNish was not Nancy's father.

He spent 23 years in the Navy in total during his life, but eventually secured a job with the New Zealand Shipping Company. After making five trips to New Zealand he moved there in 1925, leaving behind his wife and all of his carpentry tools. He worked on the waterfront in

After the expedition McNish returned to the Merchant Navy, working on various ships. He often complained that his bones permanently ached due to the conditions during the journey in the ''James Caird''; he would reportedly sometimes refuse to shake hands because of the pain. He divorced Lizzie Littlejohn on 2 March 1918, by which time he had already met his new partner, Agnes Martindale. McNish had a son named Tom and Martindale had a daughter named Nancy. Although she is mentioned frequently in his diary, it appears McNish was not Nancy's father.

He spent 23 years in the Navy in total during his life, but eventually secured a job with the New Zealand Shipping Company. After making five trips to New Zealand he moved there in 1925, leaving behind his wife and all of his carpentry tools. He worked on the waterfront in Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

until his career was ended by an injury. Destitute, he would sleep in the wharf sheds under a tarpaulin and relied on monthly collections from the dockworkers. He was found a place in the Ohiro Benevolent Home, but his health continued to deteriorate and he died on 24 September 1930, aged 56, in Wellington Hospital.

He was buried in Karori Cemetery

Karori Cemetery is New Zealand's second largest cemetery, located in the Wellington suburb of Karori.

History

Karori Cemetery opened in 1891 to address overcrowding at Bolton Street Cemetery.

In 1909, it received New Zealand's first cremato ...

, Wellington, on 26 September 1930, with full naval honours; ''HMS Dunedin

HMS ''Dunedin'' was a light cruiser of the Royal Navy, pennant number D93. She was launched from the yards of Armstrong Whitworth, Newcastle-on-Tyne on 19 November 1918 and commissioned on 13 September 1919. She has been the only ship of t ...

'' (which happened to be in port at the time) provided twelve men for the firing party and eight bearers. However, his grave remained unmarked for almost thirty years; the New Zealand Antarctic Society (NZAC) erected a headstone on 10 May 1959. In 2001, it was reported that the grave was untended and surrounded by weeds. However, in 2004 the grave was tidied and a life size bronze sculpture of McNish's beloved cat, Mrs Chippy, was placed on his grave by NZAC, having been paid for by public subscription. His grandson, Tom, believes this tribute would have meant more to him than receiving the Polar Medal.

In 1958, the British Antarctic Survey

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) is the United Kingdom's national polar research institute. It has a dual purpose, to conduct polar science, enabling better understanding of global issues, and to provide an active presence in the Antarctic on ...

named a small island in his honour, McNeish Island, which lies in the approaches to King Haakon Bay, South Georgia. The island was renamed McNish Island in 1998 after his birth certificate was presented to the United Kingdom Antarctic Place-Names Committee

The UK Antarctic Place-Names Committee (or UK-APC) is a United Kingdom government committee, part of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, responsible for recommending names of geographical locations within the British Antarctic Territory (BAT) and ...

.

On 18 October 2006, a small oval wall plaque commemorating his achievements was unveiled at the Port Glasgow Library in his home town, and earlier in the same year he was the subject of an exhibition at the McLean Museum

The McLean Museum and Art Gallery (now officially the Watt Institution) is a museum and art gallery situated in Greenock, Inverclyde, Scotland. It is the main museum in the Inverclyde area, it is free to visit and was opened in 1876. Most notabl ...

, Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

. His journals are held in the Alexander Turnbull Library

The National Library of New Zealand ( mi, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa) is New Zealand's legal deposit library charged with the obligation to "enrich the cultural and economic life of New Zealand and its interchanges with other nations" (''Nat ...

in Wellington, New Zealand.

Notes

a. For the location of McNish's birth, semap

b. There was little doubt as to his skill as a shipwright even before he was called upon for the modifications to the boats. He was never seen to take measurements, producing perfect work by eye. Macklin commented that all the work he did was first class, and even

Thomas Orde-Lees

Major (United Kingdom), Major Thomas Hans Orde-Lees, Order of the British Empire, OBE, Air Force Cross (United Kingdom), AFC (23 May 1877 – 1 December 1958) was a member of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914&n ...

, who disliked him, grudgingly admitted he was an "expert wooden ship's man".

c. "Mrs" Chippy was discovered to be a male a month after the voyage started, but by that time the name had stuck.

d. "Wife" in this source probably refers to Agnes Martindale, who was his partner but not his wife. McNish was already divorced by this time.

Citations

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:McNish, Harry 1874 births 1930 deaths British Merchant Navy personnel Burials at Karori Cemetery Explorers of Antarctica Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition People from Port Glasgow Scottish emigrants to New Zealand Scottish explorers Scottish sailors