Harriet Grote on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harriet Grote (1792–1878) was an English

Harriet Grote (1792–1878) was an English

From 1838, the Grotes also kept a country house at

From 1838, the Grotes also kept a country house at

Harriet Grote (1792–1878) was an English

Harriet Grote (1792–1878) was an English biographer

Biographers are authors who write an account of another person's life, while autobiographers are authors who write their own biography.

Biographers

Countries of working life: Ab=Arabia, AG=Ancient Greece, Al=Australia, Am=Armenian, AR=Ancient Rome ...

. She was married to George Grote

George Grote (; 17 November 1794 – 18 June 1871) was an English political radical and classical historian. He is now best known for his major work, the voluminous ''History of Greece''.

Early life

George Grote was born at Clay Hill near Be ...

and was acquatined with many of the English philosophical radicals of the earlier 19th century. A longterm friend described her as "absolutely unconventional".

Background

Her father, Thomas Lewin (1753–1837) spent some years in theMadras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

civil service. He returned to Europe, travelling from Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

in a ship with Madame Grand. Lewin remained with her for a time in Paris in the 1780s.

Settling in England, Lewin in 1784 married Mary Hale (died 1843). She was the daughter of General John Hale and Mary Chaloner, daughter of William Chaloner of Gisborough. Mrs Hale was a noted society beauty, the model in ''Mrs Hale as Euphrosyne'', a mythological painting—Euphrosyne

Euphrosyne (; grc, Εὐφροσύνη), in ancient Greek religion and mythology, was one of the Charites, known in ancient Rome as the ''Gratiae'' (Graces). She was sometimes called Euthymia (Εὐθυμία) or Eutychia (Εὐτυχία).

Fa ...

being one of the Three Graces—from 1764 by Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an English painter, specialising in portraits. John Russell said he was one of the major European painters of the 18th century. He promoted the "Grand Style" in painting which depend ...

. John Hale, on the other hand, was a radical involved in the Yorkshire Association

Christopher Wyvill (1740–1822) was an English cleric and landowner, a political reformer who inspired the formation of the ''Yorkshire Association'' movement in 1779.

The American Revolutionary War had forced the government of Lord North to ...

of the 1780s, something of which Harriet was conscious (letter of her husband to John Walker Ord).

Harriet Lewin, the second daughter, was born at The Ridgeway

The ancient tree-lined path winds over the downs countryside

The Ridgeway is a ridgeway or ancient trackway described as Britain's oldest road. The section clearly identified as an ancient trackway extends from Wiltshire along the chalk r ...

, near Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, on 1 July 1792. The Lewins had a large family, lived in style, and kept a London house as well as one in the country.

Marriage

The Lewins were living at The Hollies, nearBexley

Bexley is an area of south-eastern Greater London, England and part of the London Borough of Bexley. It is sometimes known as Bexley Village or Old Bexley to differentiate the area from the wider borough. It is located east-southeast of Char ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, when at the age of 22, Harriet was introduced by George Warde Norman

George Warde Norman (1793–1882) was an English director of the Bank of England, known as a writer on finance.

Early life

He was born at Bromley Common, Kent, on 20 September 1793, the son of George Norman, a merchant in the Norway timber trade ...

to George Grote. Peter Elmsley

Peter Elmsley (born Hampstead, London, 5 February 1774 – died Oxford, 8 March 1825) was an English classical scholar.

Early life and education

Peter Elmsley was the younger son of Alexander Elmsley of St Clement Danes, Westminster, who ...

, living at St Mary Cray

St Mary Cray is an area of South East London, England, within the London Borough of Bromley. Historically it was a market town in the county of Kent. It is located north of Orpington, and south-east of Charing Cross.

History

The name Cra ...

, allegedly in 1815 falsely claimed to George that he was engaged to Harriet.

George and Harriet were wed in a clandestine marriage at Bexley Church, after a two-year engagement and resistance to the match from George's father; it was made known in March 1820. Harriet wrote that she and George had "met but seldom". In fact her father had been turning George away from The Hollies. Despite the obstacles, this courtship period was for Harriet one of reading guided by George: political economy

Political economy is the study of how Macroeconomics, economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and Economy, national economies) and Politics, political systems (e.g. law, Institution, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied ph ...

and utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

, atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

, and the views of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

and Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book '' An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

.

For most of her engagement, Harriet Grote had been living with relations at Merley House, Wimborne

Merley House in Wimborne Minster, Wimborne, Dorset, England, is a building of historical significance and is Grade I listed on the English Heritage Register. It was built in 1752 by the bibliophile Ralph Willett and remained in the Willett family ...

.

Harriet and George were married by the Rev. Edward Barnard, vicar of Bexley, and the ceremony took place early in March 1820, according to Harriet's account.

Residences

The Grotes lived in their early married days in London'sThreadneedle Street

Threadneedle Street is a street in the City of London, England, between Bishopsgate at its northeast end and Bank junction in the southwest. It is one of nine streets that converge at Bank. It lies in the ward of Cornhill.

History

The stree ...

, in a house next to Prescott & Grote, the Grote family bank.

George Grote the elder and his wife Selina were living in Badgemore

Badgemore is the site of an ancient manor situated West of Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire.

History

William the Conqueror gave Henry de Ferrers a considerable number of manors including Badgemore in Oxfordshire. In the early 19th century the hous ...

, and Harriet and George paid a visit after their marriage, in autumn 1820. Harriet, "herself possessed of a domineering character", did not enjoy Selina's nearly uncontested regime of a strict, somewhat gloomy and exclusive evangelicalism, which she characterised as "positively disheartening" and affecting the home with "dullness and vapidity". In Selina's letters, Harriet and George occur in 1826, paying a visit to the Grote home at Beckenham

Beckenham () is a town in Greater London, England, within the London Borough of Bromley, in Greater London. Until 1965 it was part of the historic county of Kent. It is located south-east of Charing Cross, situated north of Elmers End and E ...

, and later that year attending a muster of Grote sons for the wedding of George's sister Selina to Edward Frederick. From a large family, George's brother John Grote

John Grote (5 May 1813, Beckenham – 21 August 1866, Trumpington, Cambridgeshire) was an English moral philosopher and Anglican clergyman.

Life and career

The son of a banker, John Grote was younger brother to the historian, philosopher and ...

, who became a distinguished Cambridge academic, was then still a boy. George and John came to share interests in philosophy. While Sidney Gelber has cast some doubt on whether Harriet and John got on well, Alexander Bain thought that the brothers had a good relationship, and Gibbins considers that for the 1830s the evidence is that all three were on good terms.

In 1826 Harriet and George bought a small house in Stoke Newington

Stoke Newington is an area occupying the north-west part of the London Borough of Hackney in north-east London, England. It is northeast of Charing Cross. The Manor of Stoke Newington gave its name to Stoke Newington the ancient parish.

The ...

. The elder George Grote died in 1830, with the consequence that George the younger became independently wealthy. Selina moved to Clapham Common

Clapham Common is a large triangular urban park in Clapham, south London, England. Originally common land for the parishes of Battersea and Clapham, it was converted to parkland under the terms of the Metropolitan Commons Act 1878. It is of gr ...

.

From 1832 to 1837, the Grotes lived mainly at Dulwich Wood

Dulwich Wood, together with the adjacent Sydenham Hill Wood, is the largest extant part of the ancient Great North Wood in the London Borough of Southwark.

. Then, moving nearer Parliament, they lived at 3 Eccleston Street, off Chester Square

Chester Square is an elongated residential garden square in London's Belgravia district. It was developed by the Grosvenor family, as were the nearby Belgrave and Eaton Square. The square is named after the city of Chester, the city nearest t ...

. According to William Thomas, Harriet "aspired to be a radical hostess, and to make her house in Ecclestone Street a radical Holland House

Holland House, originally known as Cope Castle, was an early Jacobean country house in Kensington, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

."

The Grotes moved in 1848 within London's West End to 12 Savile Row

Savile Row (pronounced ) is a street in Mayfair, central London. Known principally for its traditional bespoke tailoring for men, the street has had a varied history that has included accommodating the headquarters of the Royal Geographical ...

.

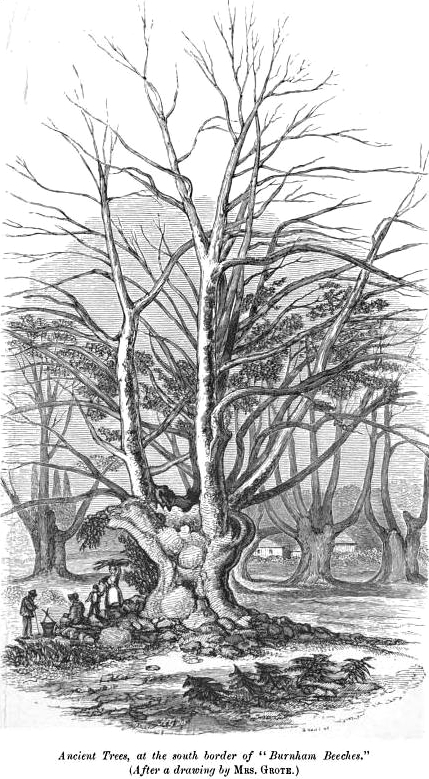

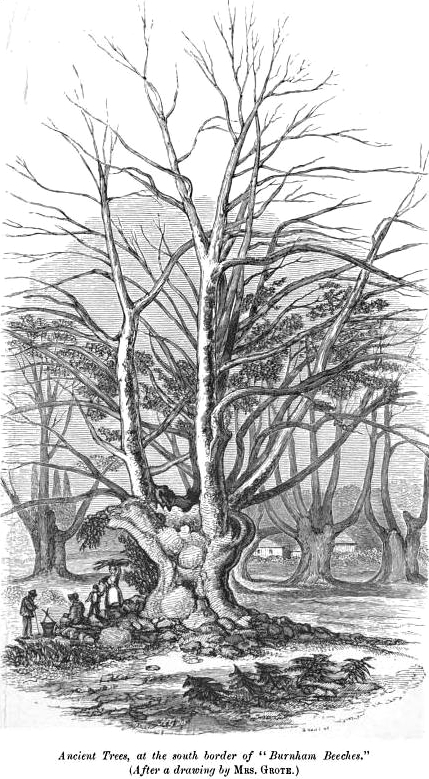

Country place at East Burnham, and the History Hut

From 1838, the Grotes also kept a country house at

From 1838, the Grotes also kept a country house at East Burnham

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

, near Burnham Beeches

Burnham Beeches is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest situated west of Farnham Common in the village of Burnham, Buckinghamshire. The southern half is owned by the Corporation of London and is open to the public. It is also a Na ...

in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

. The "weird picturesqueness" of Burnham Beeches became popular when the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

was constructed, with stations a few miles away.

They lived first at East Burnham Cottage. It was associated with Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Irish satirist, a politician, a playwright, poet, and long-term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. He is known for his plays such as ''The Rivals'', ''The Sc ...

, his future wife Elizabeth Ann Linley

Elizabeth Ann Sheridan ( Linley; September 1754 – 28 June 1792) was an 18th-century English singer who was known to have possessed great beauty. She was the subject of several paintings by Thomas Gainsborough, who was a family friend, Joshu ...

, and her escape from an importunate suitor. There was a portrait of Elizabeth by Joshua Reynolds at The Hollies, Harriet's parental home.

East Burnham Cottage was replaced by a small house, which they had built in the neighbourhood and occupied under the name of "History Hut", from the beginning of 1853 until the end of 1857. It was in fact Harriet's project, "a small Elizabethan house to be built in Popple's Park", undertaken from 1852, once profits from the multi-volume ''History of Greece'' began to accrue. Harriet had given support to this, George Grote's major scholarly work, from the outset, suggesting the title and dealing with the publisher. She had a bowl of punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

made, for Christmas 1855, to celebrate at the History Hut the completion of its 12 volumes.

Then for reasons detailed by Harriet Grote in her ''Account of the Hamlet of East Burnham'', they decided to leave the area. According to Francis George Heath, writing on Burnham Beeches in 1879, "no right of estovers

In English law, an estover is an allowance made to a person out of an estate, or other thing, for his or her support. The word estover can also mean specifically an allowance of wood that a tenant is allowed to take from the commons, for life o ...

has belonged to the commoners of East Burnham, and the lord of the manor ... had alone the sole right of touching the trees." Grote's work deals in part with "commoners' rights and privileges, and ... her efforts to maintain them on behalf of her poor neighbours". In 1885, when the East Burnham Common was bought by the Corporation of London

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the municipal governing body of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United King ...

, it was considered that the commoners had rights of pasture and turbary

Turbary is the ancient right to cut turf, or peat, for fuel on a particular area of bog. The word may also be used to describe the associated piece of bog or peatland and, by extension, the material extracted from the turbary. Turbary rights, whic ...

, but not estovers. There is evidence, however, that pollarding

Pollarding is a pruning system involving the removal of the upper branches of a tree, which promotes the growth of a dense head of foliage and branches. In ancient Rome, Propertius mentioned pollarding during the 1st century BCE. The practice oc ...

of the trees did occur in conjunction with pasturage.

The park land on which the History Hut was built was purchased in 1844 by George Grote from Robert Gordon Robert Gordon may refer to:

Entertainment

* Robert Gordon (actor) (1895–1971), silent-film actor

* Robert Gordon (director) (1913–1990), American director

* Robert Gordon (singer) (1947–2022), American rockabilly singer

* Robert Gordon (scr ...

. Another aspect of ''Account of the Hamlet of East Burnham'' was Harriet's tracing of the descent of the old East Burnham House from Charles Eyre (died 1786) to Gordon. That house had been demolished by Gordon c.1837; the name continued, attached to the History Hut.

Later life

During the 1850s Grote promoted the Society of Female Artists.Augustus Hare

Augustus John Cuthbert Hare (13 March 1834 – 22 January 1903) was an English writer and raconteur.

Early life

He was the youngest son of Francis George Hare of Herstmonceux, East Sussex, and Gresford, Flintshire, Wales, and nephew of ...

described a visit she made to Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in 1857:

"Mrs Grote sat with one leg over the other, both high in the air, and talked for two hours, turning with equal facility to Saffi on Italian Literature,From 1859, the Grotes took Barrow Green Court inMax Müller Friedrich Max Müller (; 6 December 1823 – 28 October 1900) was a German-born philologist and Orientalist, who lived and studied in Britain for most of his life. He was one of the founders of the western academic disciplines of Indian ...on Epic Poetry, andArthur Arthur is a common male given name of Brittonic languages, Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. An ...on Ecclesiastical History, and then plunged into a discourse on the best manure for turnips, and the best way of forcingCotswold The Cotswolds (, ) is a region in central-southwest England, along a range of rolling hills that rise from the meadows of the upper Thames to an escarpment above the Severn Valley and Evesham Vale. The area is defined by the bedrock of Juras ...mutton, with an interlude first upon the 'harmony of shadow' in water-colour drawing, and then upon rat-hunts at Jemmy Shawe's – a low public-house inWestminster Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster. The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu .... Upon all these subject she was equally vigorous, and gave all her decisions with the manner and tone of one laying down the laws of Athens...Augustus Hare Augustus John Cuthbert Hare (13 March 1834 – 22 January 1903) was an English writer and raconteur. Early life He was the youngest son of Francis George Hare of Herstmonceux, East Sussex, and Gresford, Flintshire, Wales, and nephew of ..., ''The Story of My Life'', Volume I (Dodd, Mead and Company, New York, 1896), p. 431.

Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

, which had once been occupied by Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

. The marriage was under threat during the early 1860s, when George (on Harriet's account) became infatuated with Susan Durant. They left Barrow Green Court in 1863. In 1864 they settled finally at Shere

Shere is a village in the Guildford district of Surrey, England east south-east of Guildford and west of Dorking, centrally bypassed by the A25. It is a small still partly agricultural village chiefly set in the wooded 'Vale of Holmesdale' b ...

, Surrey, at The Ridgeway, as it was called by Harriet after the place of her birth.

In a piece published in her ''Collected Papers'', on the law of marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between ...

, Harriet Grote wrote

...I maintain, and shall maintain to the end, that the first of all remedial measures to be sought for by women, and for which they should clamour, beg, and agitate, is "equality of rights over property with the other sex."George Grote had been a party in a chancery case on such a matter, ''Peters v Grote'', of 1835, occurring in the family of a radical reformer (see

Henry Revell

Henry Revell (1767–1847) was a London radical of the Reform Bill period, a leading figure in the National Political Union (England), National Political Union.

Early life

He was the eldest son of John Read of Walthamstow, known in early life a ...

). With this legal side as priority, Harriet did become involved in other women's issues. She supported the Langham Place circle

The ''English Woman's Journal'' was a periodical dealing primarily with female employment and equality issues. It was established in 1858 by Barbara Bodichon, Matilda Mary Hays and Bessie Rayner Parkes. Published monthly between March 1858 an ...

. She contributed to the ''Victoria Regia'' of Adelaide Anne Procter

Adelaide Anne Procter (30 October 1825 – 2 February 1864) was an English poet and philanthropist.

Her literary career began when she was a teenager, her poems appearing in Charles Dickens's periodicals ''Household Words'' and '' All the ...

in 1861, with an essay ''On Art, Ancient and Modern''. Her niece Sarah Lewin acted as secretary of the associated Society for Promoting the Employment of Women

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW) was one of the earliest British women's organisations.

The society was established in 1859 by Jessie Boucherett, Barbara Bodichon and Adelaide Anne Proctor to promote the training and emp ...

, which Harriet also supported. She was close to the activist Lady Amberley. Her social views generally are taken to be "radical-individualist".

Harriet signed the suffrage petition of 1866. She spoke at the first public meeting of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage in 1869. She spoke again at Clementia Taylor

Clementia Taylor (Name at birth, née Doughty; 17 December 1810 – 11 April 1908) was an English women's rights activist and radical.''ODNB''.

Life

Clementia (known as Mentia to her friends) was born in Brockdish, Norfolk, one of twelve childr ...

's 1870 meeting in the Hanover Square Rooms, her suffragist arguments being reported by Helen Blackburn

Helen Blackburn (25 May 1842 – 11 January 1903) was a feminist, writer and campaigner for women's rights, especially in the field of employment. Blackburn was an editor of the ''Englishwoman's Review'' magazine. She wrote books about women work ...

.

She remained active to the last. W. E. Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

met Mark Pattison at her home in 1875. She died at Shere on 29 December 1878, in her 87th year, and was buried there. Biographical works appeared, by Jules Fournet in 1879, and by Lady Eastlake

Elizabeth, Lady Eastlake (17 November 1809 – 2 October 1893), born Elizabeth Rigby, was an English author, art critic and art historian, who made regular contributions for the ''Quarterly Review''. She is known not only for her writing but also ...

in 1880.

Associations

Her marriage detached Harriet Grote from the gentry circles in which she had been brought up. ThePhilosophical Radicals

The Philosophical Radicals were a philosophically-minded group of English political radicals in the nineteenth century inspired by Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and James Mill (1773–1836). Individuals within this group included Francis Place (177 ...

, who formed George's intellectual and social circle, she found dour, theoretical and irreligious. A number of them were near neighbours in Threadneedle Street, in particular Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

and James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of British ...

. There were regular mornings with Charles Buller

Charles Buller (6 August 1806 – 29 November 1848) was a British barrister, politician and reformer.

Background and education

Born in Calcutta, British India, Buller was the son of Charles Buller (1774–1848), a member of a well-known Corn ...

, John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

, Thomas Eyton Tooke and others. An overlapping discussion group on political economy, in which Harriet also joined and which she called the "Brangles", included too David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British Political economy, political economist. He was one of the most influential of the Classical economics, classical economists along with Thomas Robert Malthus, Thomas Malthus, Ad ...

and John Ramsay McCulloch

John Ramsay McCulloch (1 March 1789 – 11 November 1864) was a Scottish economist, author and editor, widely regarded as the leader of the Ricardian school of economists after the death of David Ricardo in 1823. He was appointed the first pr ...

.

Of old friends, and not of interest to George, Harriet retained the Plumers of Gilston Park

Gilston Park is a Grade II* listed country house in Gilston, Hertfordshire, England. It was designed by Philip Hardwick

Philip Hardwick (15 June 1792 in London – 28 December 1870) was an English architect, particularly associated with rai ...

; William Plumer (1736–1822)

William Plumer (1736–1822) was a British politician who served 54 years in the House of Commons between 1763 and 1822.

Life

Plumer was the son of William Plumer and his wife Elizabeth Byde, daughter of Thomas Byde of Ware Park, and was born on ...

MP, close to Lord William Bentinck

Lieutenant General Lord William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (14 September 177417 June 1839), known as Lord William Bentinck, was a British soldier and statesman who served as the Governor of Fort William (Bengal) from 1828 to 1834 and the First G ...

, was a "distant cousin" of the Lewins, and Lord William and his wife befriended Harriet. Her naval brother Richard John Lewin married in 1825 Plumer's widow Jane, daughter of George Hamilton, but died after two years. Harriet arranged a small dinner for the purpose of discussion between James Mill and Lord William, shortly before the latter sailed to become Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

in 1828.

During George Grote's parliamentary period, from 1832 to 1841, Harriet supported him by holding together the party of radical reformers socially. Indeed, in letters such as she wrote to Francis Place

Francis Place (3 November 1771 in London – 1 January 1854 in London) was an English social reformer.

Early life

He was an illegitimate son of Simon Place and Mary Gray. His father was originally a journeyman baker. He then became a Marshalse ...

, she was more assertive than that, playing a leadership role. Both Place and Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 – 2 April 1865) was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti-Corn Law League and the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty.

As a young ...

were under the impression that, had she been a man, she could have emerged as the leader of the Philosophical Radicals. George and Harriet took under their wing Sir William Molesworth, 8th Baronet

Sir William Molesworth, 8th Baronet, (23 May 181022 October 1855) was a Radical British politician, who served in the coalition cabinet of The Earl of Aberdeen from 1853 until his death in 1855 as First Commissioner of Works and then Secret ...

, a radical MP from 1832, and Harriet became "his mentor and confidante", a relationship lasting until his marriage in 1844.

Later, Harriet Grote's social circle was broad: it has been described as "an extensive group of (mainly but not exclusively) liberal and radical intellectuals, politicians, writers and artists." One opinion was that Harriet Grote had

a most curious salon, where practically all worlds met, artists as well as savants and politicians, and which was quite assiduously frequented by, among others,John Stuart Mill John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ..., Carlyle and his wife, Cornwall Lewis, Sidney Smith, not to mention Thalberg, Lablache, and, during his visits to London, Mendelssohn ../blockquote> The witSydney Smith Sydney Smith (3 June 1771 – 22 February 1845) was an English wit, writer, and Anglican cleric. Early life and education Born in Woodford, Essex, England, Smith was the son of merchant Robert Smith (1739–1827) and Maria Olier (1750–1801), ...coined "queen of the radicals" for Harriet, but also the unkind quip that she was the origin of the termgrotesque Since at least the 18th century (in French and German as well as English), grotesque has come to be used as a general adjective for the strange, mysterious, magnificent, fantastic, hideous, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting, and thus ....

The musical world

An accomplished musician, Grote cultivated friendly relations with performers includingJenny Lind Johanna Maria "Jenny" Lind (6 October 18202 November 1887) was a Swedish opera singer, often called the "Swedish Nightingale". One of the most highly regarded singers of the 19th century, she performed in soprano roles in opera in Sweden and a ....Richard Monckton Milnes Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, FRS (19 June 1809 – 11 August 1885) was an English poet, patron of literature and a politician who strongly supported social justice. Background and education Milnes was born in London, the son of ...wrote to Sophia MacCarthy, wife ofCharles Justin MacCarthy Sir Charles Justin MacCarthy (1811–1864) was the 12th Governor of British Ceylon and the 12th Accountant General and Controller of Revenue. He was appointed on 22 October 1860 and was Governor until 1 December 1863. He also served as acting gov ..., in 1849 about an important passage in Lind's emotional life:Jenny Lind's marriage is again deferred. She cannot make up her mind to marry a very good, good-looking, infinitely stupid man she has engaged herself to, and at the same time has not the cruelty to throw him over; so she goes to Paris, to Mrs Grote, for a month or two, when she is to give her final decision.

French connections

Thomas Lewin, Harriet's father, was an admirer of French literature. Harriet first visited Paris in 1817. By 1827 she was corresponding on political economy withJean Baptiste Say Jean-Baptiste Say (; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a liberal French economist and businessman who argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law—also known as the law of .... In May 1830, the Grotes were in Paris, staying also at theChâteau de la Grange-Bléneau A château (; plural: châteaux) is a manor house or residence of the lord of the manor, or a fine country house of nobility or gentry, with or without fortifications, originally, and still most frequently, in French-speaking regions. Nowaday ...withGilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemasonry, freemason and military officer who fought in the Ameri .... This visit to Lafayette, on a shortened form of an intended journey toSwitzerland ). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ..., took place with an introduction fromCharles Comte François-Charles-Louis Comte (1782–1837) was a French lawyer, journalist and political writer. Biography In 1814, Comte, along with Charles Dunoyer, founded with '' Le Censeur'', a liberal journal. In 1820, he was found guilty of attacks agai ..., son-in-law of Say. It was shortly before theJuly Revolution The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...: George Grote sent money to support it, through Comte. Harriet from then on cultivated French public men. Thomas Carlyle in the late 1830s described with relish toJane Carlyle Jane Baillie Carlyle ( Welsh; 14 July 1801 – 21 April 1866) was a Scottish writer and the wife of Thomas Carlyle. She did not publish any work in her lifetime, but she was widely seen as an extraordinary letter writer. Virginia Woolf ca ...the process of Charles Buller introducing Godefroi Cavaignac to her.George Sand Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. One of the most popular writers in Europe in her lifetime, bein ...gave her writer friend Charles Duvernet a detailed briefing on what to say to Harriet on meeting. In 1852, Harriet took a political article in Paris fromAlexis de Tocqueville Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (; 29 July 180516 April 1859), colloquially known as Tocqueville (), was a French aristocrat, diplomat, political scientist, political philosopher and historian. He is best known for his works ..., on the1851 French coup d'état The Coup d'état of 2 December 1851 was a self-coup staged by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (later Napoleon III), at the time President of France under the Second Republic. Code-named Operation Rubicon and timed to coincide with the anniversary ..., and saw through Henry Reeve that it was published in London in ''The Times ''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...''.

Reputation and appearance

Charles Sumner Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...wrote toHoratio Greenough Horatio Greenough (September 6, 1805 – December 18, 1852) was an American sculptor best known for his United States government commissions '' The Rescue'' (1837–50), ''George Washington'' (1840), and ''The Discovery of America'' (1840–4 ...in 1841 about a letter of introduction to the Grotes, stating that Harriet was "a masculine person, without children, interested very much in politics, and one of the most remarkable women in England." He added that fromWilliam Ellery Channing William Ellery Channing (April 7, 1780 – October 2, 1842) was the foremost Unitarian preacher in the United States in the early nineteenth century and, along with Andrews Norton (1786–1853), one of Unitarianism's leading theologians. Channi ...he had hadCatharine Sedgwick Catharine Maria Sedgwick (December 28, 1789 – July 31, 1867) was an American novelist of what is sometimes referred to as " domestic fiction". With her work much in demand, from the 1820s to the 1850s, Sedgwick made a good living writing short ...'s opinion that Harriet was "the most remarkable woman she had met in Europe." According to Augustus Hare who had met her, "She was, to the last, one of the most original women in England, shrewd, generous, and excessively vain."G. M. Young George Malcolm Young (29 April 1882 – 18 November 1959) was an English historian, best known for his book on Victorian times in Britain, ''Portrait of an Age'' (1936). After a short time as an academic and a career as a civil servant lasting ...in an essay wrote of her:In Mrs. Grote, who would have been a far more effective Member of Parliament than her husband, who sat with her red stockings higher than her head, discomfited a dinner-party by saying "disembowelled" quite bold and plain, and knew when a hoop was off a pail in the back kitchen, the great lady is formidably ascendant ../blockquote> Minnie Simpson (1825–1907), née Mary Charlotte Mair Senior, was a daughter ofNassau Senior Nassau William Senior (; 26 September 1790 – 4 June 1864), was an English lawyer known as an economist. He was also a government adviser over several decades on economic and social policy on which he wrote extensively. Early life He was born .... She knew Harriet as a long-term family friend, and wrote in ''Many Memories of Many People'' (1898) an extended account of her as a person, initially comparing her toQueen Elizabeth I Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen". El .... It is stated there that it was the shoes that were red "which she said were admired by Sydney Smith":Her dress was characteristic; it did not change with the fashion. She always wore short skirts, noThe comment about the pail is found in Lady Eastlake's memoir, coming from a discussion of neighbours in Surrey. Minnie Simpson gives a basis for Harriet's approach to estate management, quoting a letter from the Grotes' property atcrinoline A crinoline is a stiff or structured petticoat designed to hold out a woman's skirt, popular at various times since the mid-19th century. Originally, crinoline described a stiff fabric made of horsehair ("crin") and cotton or linen which was ..., white stockings and high shoes ...Long Bennington Long Bennington is a linear village and civil parish in South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, just off the A1 road, north of Grantham and south of Newark-on-Trent. It had a population of 2,100 in 2014 and 2,018 at the 2011 Census. ....

Works

Grote wrote books: *''The Case of the Poor against the Rich, fairly considered'' (1850), anonymous. It was influenced by works of de Tocqueville andLéon Faucher Léonard Joseph (Léon) Faucher (; 8 September 1803 – 14 December 1854) was a French politician and economist. Biography Faucher was born at Limoges, Haute-Vienne. When he was nine years old the family moved to Toulouse, where the boy was se ...dealing with economics andpauperism Pauperism (Lat. ''pauper'', poor) is poverty or generally the state of being poor, or particularly the condition of being a "pauper", i.e. receiving relief administered under the English Poor Laws. From this, pauperism can also be more generally ..., in the British context. *''Some Account of the Hamlet of East Burnham'' (1858), for private circulation *''Memoir of the Life'' ofAry Scheffer Ary Scheffer (10 February 179515 June 1858) was a Dutch-French Romantic painter. He was known mostly for his works based on literature, with paintings based on the works of Dante, Goethe, and Lord Byron, as well as religious subjects. He was als ...(1860 and second edition that year) *''Collected Papers'' (1862). It included articles first published in the ''Edinburgh Review The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929. ''Edinburgh Review'', ...'', ''Westminster Review The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal until ...'' and ''The Spectator''. *''The Philosophical Radicals of 1832'' (1866, printed for private circulation). It included a ''Life'' ofSir William Molesworth, 8th Baronet Sir William Molesworth, 8th Baronet, (23 May 181022 October 1855) was a Radical British politician, who served in the coalition cabinet of The Earl of Aberdeen from 1853 until his death in 1855 as First Commissioner of Works and then Secret .... *''The Personal Life of George Grote'' (1873) *''Posthumous Papers'' (1874, for private circulation), edited by Harriet Grote, is a miscellany of materials, such as correspondence, articles andcommonplace book Commonplace books (or commonplaces) are a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. They have been kept from antiquity, and were kept particularly during the Renaissance and in the nineteenth century. Such books are simi ...entries, related to the Grotes and their circle. *''A brief Retrospect of the Political Events of 1831–1832, as illustrated by the Greville and Althorp Memoirs'' (1878), pamphlet From 1842 to 1852 she wrote in ''The Spectator ''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world. It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...''.

Family

Harriet Grote went down withpuerperal fever Postpartum infections, also known as childbed fever and puerperal fever, are any bacterial infections of the female reproductive tract following childbirth or miscarriage. Signs and symptoms usually include a fever greater than , chills, lower ab ...after the premature delivery in 1821 of the only child of her marriage, a boy who lived only a week. She was attended by Dr. Robert Batty. In later life she suffered fromneuralgia Neuralgia (Greek ''neuron'', "nerve" + ''algos'', "pain") is pain in the distribution of one or more nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Classification Under the general heading of neuralg .... George's brother Andrew Grote, of theBengal Civil Service The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947. Its members ruled over more than 300 million p ..., died in 1835, shortly after his wife; leaving two sons and two daughters as orphans. Another brother in Bengal,Arthur Grote Arthur Grote (29 November 1814 – 4 December 1886) was an English colonial administrator. Life He was born on 29 November 1814 at Beckenham in Kent, England. He was the son of George Grote (1760–1830), a London banker, and Selina Peckwell (177 ..., lost his first wife in childbirth in 1838, and sent his children home. Harriet "supposed" that she would take them in, in a letter of 1843 to her sister Frances Eliza in Stockholm, married to Neil von Koch, which said also that Andrew's eldest daughter, aged 13, was ill. That daughter was Alexandrina Jessie ("Ally" or "Allie") Grote (1831–1927), adopted by George's brother John. She marriedJoseph Bickersteth Mayor Rev. Joseph Bickersteth Mayor (24 October 1828 – 29 November 1916) was an English professor, classical scholar, and Anglican clergyman. Early life and education Mayor was born in Cape Colony''1911 England Census'' while his parents returne ...and was mother of the novelistF. M. Mayor Flora Macdonald Mayor (20 October 1872, Kingston Hill, Surrey – 28 January 1932, Hampstead, London), was an English novelist and short story writer, who published under the name F. M. Mayor. Life and work Flora MacDonald Mayor was born on 20 O .... The actorWilliam Terriss William Terriss (20 February 1847 – 16 December 1897), born as William Charles James Lewin, was an English actor, known for his swashbuckling hero roles, such as Robin Hood, as well as parts in classic dramas and comedies. He was also a nota ..., the father ofEllaline Terriss Mary Ellaline Terriss, Lady Hicks (born Mary Ellaline Lewin, 13 April 1871 – 16 June 1971), known professionally as Ellaline Terriss, was a popular British actress and singer, best known for her performances in Edwardian musical comedies. Sh ..., was Harriet's nephew, the son of her brother George Herbert Lewin and his wife Mary Friend."The Terriss Tragedy", in ''New York Dramatic Mirror The ''New York Dramatic Mirror'' (1879–1922) was a prominent theatrical trade newspaper. History The paper was founded in January 1879 by Ernest Harvier as the ''New York Mirror''. In stating its purpose to cover the theater, it proclaimed t ...'', 21 December 1897

Notes

External links

*

Victorian Commons blogpost 4 January 2021, ''"Had she been a man, she would have been the leader of a party": Harriet Grote (1792-1878), radicalism and Parliament, 1820-41'', Martin Spychal

Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Grote, Harriet 1792 births 1878 deaths 19th-century English women writers 19th-century English writers Writers from Southampton English political hostesses Society of Women Artists members