Harriet Ann Jacobs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harriet Jacobs (1813 or 1815 – March 7, 1897) was an

When Jacobs was six years old, her mother died. She then lived with her owner, a daughter of the deceased tavern keeper, who taught her not only to sew, but also to read and write. Only very few slaves were literate, although it was only in 1830 that North Carolina explicitly outlawed teaching slaves to read or write. Although Harriet's brother John succeeded in teaching himself to read, Jacobs, ''Incidents''br>94

When Jacobs was six years old, her mother died. She then lived with her owner, a daughter of the deceased tavern keeper, who taught her not only to sew, but also to read and write. Only very few slaves were literate, although it was only in 1830 that North Carolina explicitly outlawed teaching slaves to read or write. Although Harriet's brother John succeeded in teaching himself to read, Jacobs, ''Incidents''br>94

/ref> he still wasn't able to write when he escaped from slavery as a young adult. J.Jacobs, ''Tale''br>126

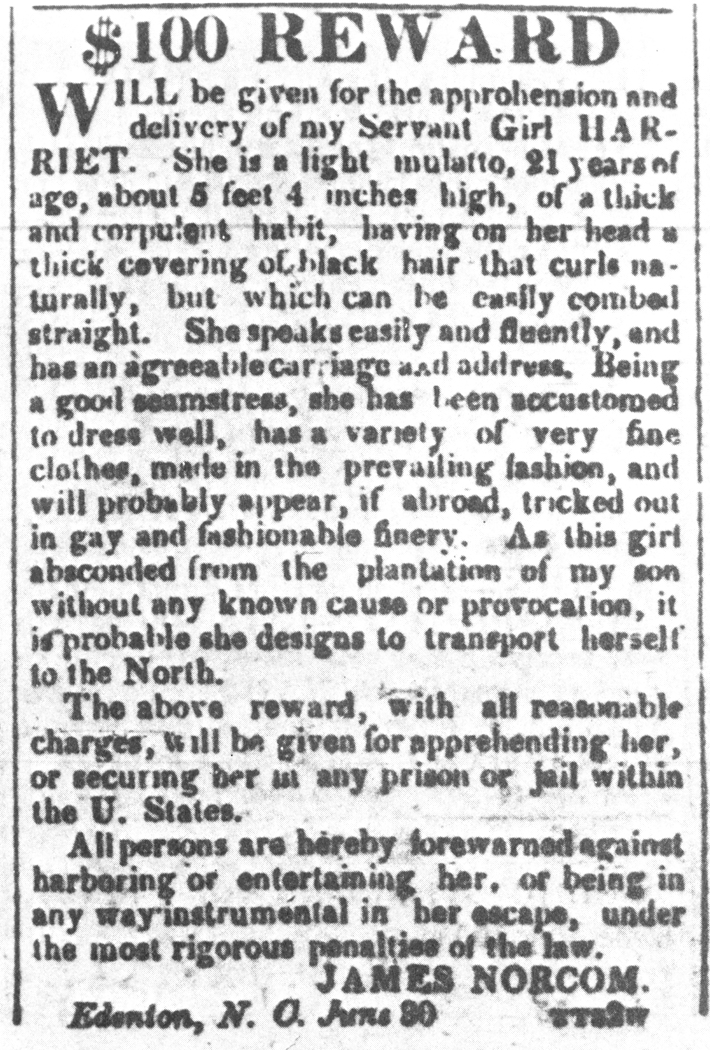

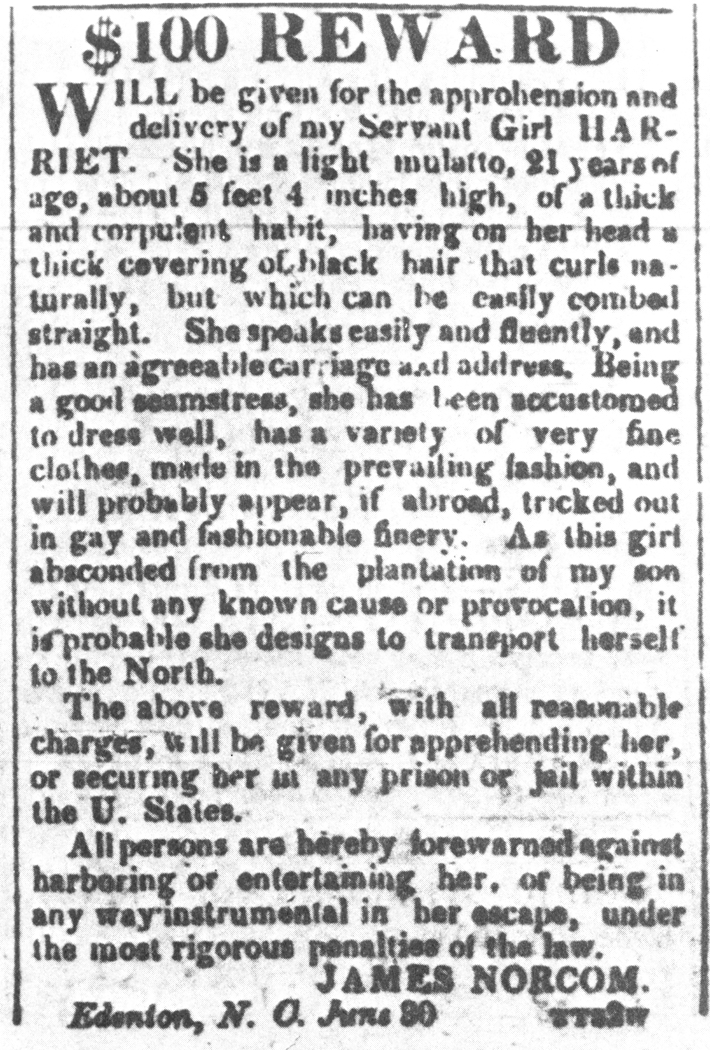

/ref> In 1825, the owner of Harriet and John Jacobs died. She willed Harriet to her three-year-old niece Mary Matilda Norcom. Mary Matilda's father, the physician Dr. James Norcom (son-in-law of the deceased tavern keeper), became her ''de facto'' master. Her brother John and most of her other property was inherited by the tavern keeper's widow. Dr. Norcom hired John, so that the Jacobs siblings lived together in his household. Following the death of the widow, her slaves were sold at the New Year's Day auction, 1828. Among them were Harriet's brother John, her grandmother Molly Horniblow and Molly's son Mark. Being sold at public auction was a traumatic experience for twelve-year old John. Friends of hers bought Molly Horniblow and Mark with money Molly had been working hard to save over the many years of her servitude at the tavern. Afterwards Molly Horniblow was set free, and her own son Mark became her slave. Because of legal restrictions on

Norcom reacted by selling her children and her brother John to a slave trader demanding that they should be sold in a different state, thus expecting to separate them forever from their mother and sister. However, the trader was secretly in league with Sawyer, to whom he sold all three of them, thus frustrating Norcom's plan on revenge. In her autobiography, Jacobs accuses Sawyer of not having kept his promise to legally manumit their children. Still, Sawyer allowed his enslaved children to live with their great-grandmother Molly Horniblow. After Sawyer married in 1838, Jacobs asked her grandmother to remind him of his promise. He asked and obtained Jacobs's approval to send their daughter to live with his cousin in Brooklyn, New York, where slavery had already been abolished. He also suggested to send their son to the Free States. While locked in her cell, Jacobs could often observe her unsuspecting children.

Norcom reacted by selling her children and her brother John to a slave trader demanding that they should be sold in a different state, thus expecting to separate them forever from their mother and sister. However, the trader was secretly in league with Sawyer, to whom he sold all three of them, thus frustrating Norcom's plan on revenge. In her autobiography, Jacobs accuses Sawyer of not having kept his promise to legally manumit their children. Still, Sawyer allowed his enslaved children to live with their great-grandmother Molly Horniblow. After Sawyer married in 1838, Jacobs asked her grandmother to remind him of his promise. He asked and obtained Jacobs's approval to send their daughter to live with his cousin in Brooklyn, New York, where slavery had already been abolished. He also suggested to send their son to the Free States. While locked in her cell, Jacobs could often observe her unsuspecting children.

In 1843 Jacobs heard that Norcom was on his way to New York to force her back into slavery, which was legal for him to do everywhere inside the United States. She asked Mary Willis for a leave of two weeks and went to her brother John in

In 1843 Jacobs heard that Norcom was on his way to New York to force her back into slavery, which was legal for him to do everywhere inside the United States. She asked Mary Willis for a leave of two weeks and went to her brother John in

John S. Jacobs got more and more involved with abolitionism, i. e. the anti-slavery movement led by

John S. Jacobs got more and more involved with abolitionism, i. e. the anti-slavery movement led by

When Jacobs came to know the Posts in Rochester, they were the first white people she met since her return from England, who didn't look down on her color. Soon, she developed enough trust in Amy Post to be able to tell her her story which she had kept secret for so long. Post later described how difficult it was for Jacobs to tell of her traumatic experiences: "Though impelled by a natural craving for human sympathy, she passed through a baptism of suffering, even in recounting her trials to me. ... The burden of these memories lay heavily on her spirit".

In late 1852 or early 1853, Amy Post suggested that Jacobs should write her life story. Jacobs's brother had for some time been urging her to do so, and she felt a moral obligation to tell her story to help build public support for the antislavery cause and thus save others from suffering a similar fate.

Still, Jacobs had acted against moral ideas commonly shared in her time, including by herself, by consenting to a sexual relationship with Sawyer. The shame caused by this memory and the resulting fear of having to tell her story had been the reason for her initially avoiding contact with the abolitionist movement her brother John had joined in the 1840s. Finally, Jacobs overcame her trauma and feeling of shame, and she consented to publish her story. Her reply to Post describing her internal struggle has survived.

When Jacobs came to know the Posts in Rochester, they were the first white people she met since her return from England, who didn't look down on her color. Soon, she developed enough trust in Amy Post to be able to tell her her story which she had kept secret for so long. Post later described how difficult it was for Jacobs to tell of her traumatic experiences: "Though impelled by a natural craving for human sympathy, she passed through a baptism of suffering, even in recounting her trials to me. ... The burden of these memories lay heavily on her spirit".

In late 1852 or early 1853, Amy Post suggested that Jacobs should write her life story. Jacobs's brother had for some time been urging her to do so, and she felt a moral obligation to tell her story to help build public support for the antislavery cause and thus save others from suffering a similar fate.

Still, Jacobs had acted against moral ideas commonly shared in her time, including by herself, by consenting to a sexual relationship with Sawyer. The shame caused by this memory and the resulting fear of having to tell her story had been the reason for her initially avoiding contact with the abolitionist movement her brother John had joined in the 1840s. Finally, Jacobs overcame her trauma and feeling of shame, and she consented to publish her story. Her reply to Post describing her internal struggle has survived.

In June 1853, Jacobs chanced to read a defense of slavery entitled "The Women of England vs. the Women of America" in an old newspaper. Written by

In June 1853, Jacobs chanced to read a defense of slavery entitled "The Women of England vs. the Women of America" in an old newspaper. Written by

In May 1858, Harriet Jacobs sailed to England, hoping to find a publisher there. She carried good letters of introduction, but wasn't able to get her manuscript into print. The reasons for her failure are not clear. Yellin supposes that her contacts among the British abolitionists feared that the story of her liaison with Sawyer would be too much for Victorian Britain's prudery. Disheartened, Jacobs returned to her work at Idlewild and made no further efforts to publish her book until the fall of 1859.

On October 16, 1859, the anti-slavery activist

In May 1858, Harriet Jacobs sailed to England, hoping to find a publisher there. She carried good letters of introduction, but wasn't able to get her manuscript into print. The reasons for her failure are not clear. Yellin supposes that her contacts among the British abolitionists feared that the story of her liaison with Sawyer would be too much for Victorian Britain's prudery. Disheartened, Jacobs returned to her work at Idlewild and made no further efforts to publish her book until the fall of 1859.

On October 16, 1859, the anti-slavery activist

After the

After the

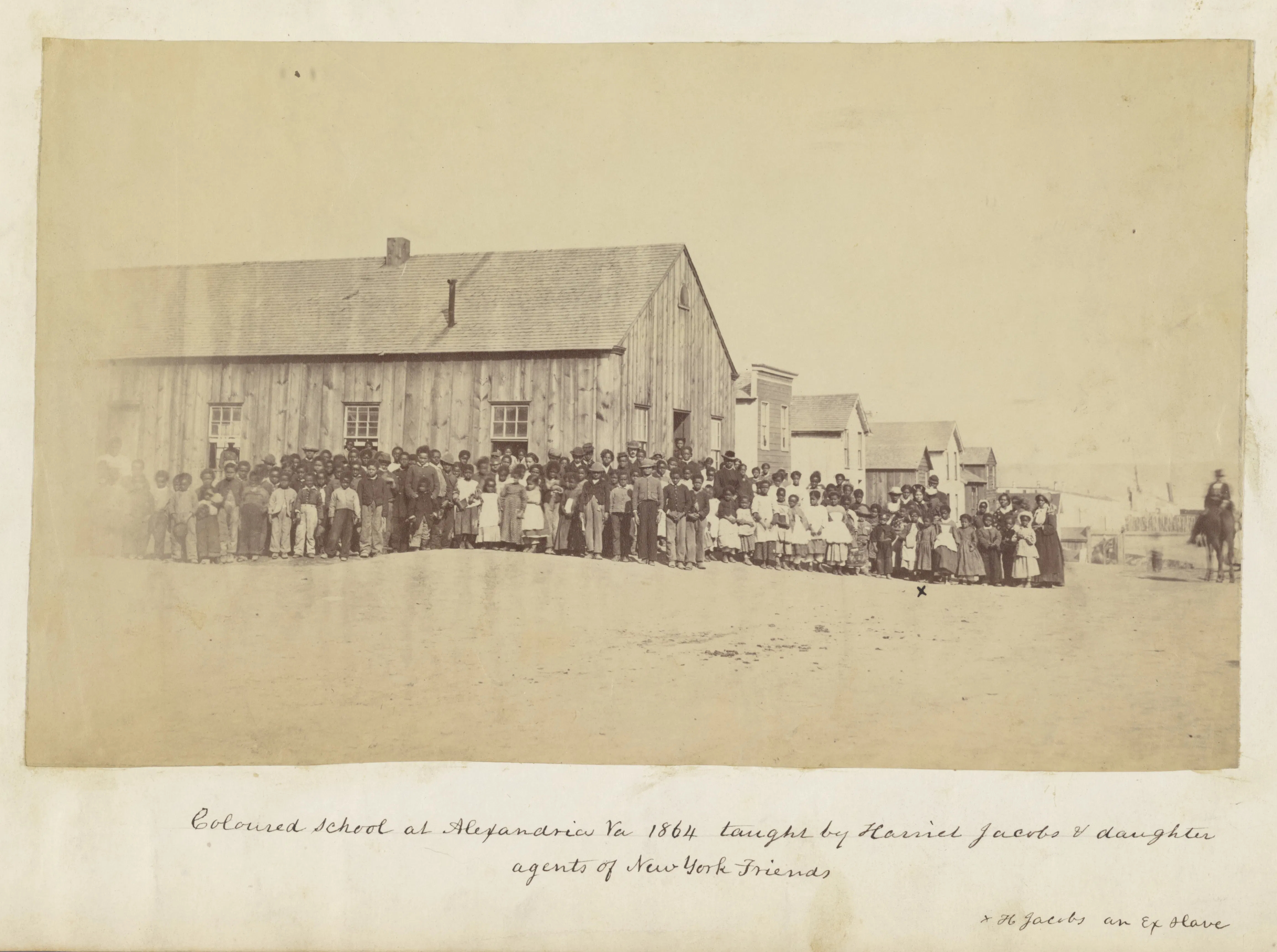

In most slave states, teaching slaves to read and write had been forbidden. Virginia had even prohibited teaching these skills to free blacks. After Union troops occupied Alexandria in 1861, some schools for blacks emerged, but there was not a single free school under African American control. Jacobs supported a project conceived by the black community in 1863 to found a new school. In the fall of 1863 her daughter Louisa Matilda who had been trained as a teacher, came to Alexandria in the company of Virginia Lawton, a black friend of the Jacobs family. After some struggle with white missionaries from the North who wanted to take control of the school, the ''Jacobs School'' opened in January 1864 under Louisa Matilda's leadership. In the ''National Anti-Slavery Standard'', Harriet Jacobs explained that it was not disapproval of white teachers that made her fight for the school being controlled by the black community. But she wanted to help the former slaves, who had been raised "to look upon the white race as their natural superiors and masters", to develop "respect for their race".

Jacobs's work in Alexandria was recognized on the local as well as on the national level, especially in abolitionist circles. In the spring of 1864 she was elected to the executive committee of the

In most slave states, teaching slaves to read and write had been forbidden. Virginia had even prohibited teaching these skills to free blacks. After Union troops occupied Alexandria in 1861, some schools for blacks emerged, but there was not a single free school under African American control. Jacobs supported a project conceived by the black community in 1863 to found a new school. In the fall of 1863 her daughter Louisa Matilda who had been trained as a teacher, came to Alexandria in the company of Virginia Lawton, a black friend of the Jacobs family. After some struggle with white missionaries from the North who wanted to take control of the school, the ''Jacobs School'' opened in January 1864 under Louisa Matilda's leadership. In the ''National Anti-Slavery Standard'', Harriet Jacobs explained that it was not disapproval of white teachers that made her fight for the school being controlled by the black community. But she wanted to help the former slaves, who had been raised "to look upon the white race as their natural superiors and masters", to develop "respect for their race".

Jacobs's work in Alexandria was recognized on the local as well as on the national level, especially in abolitionist circles. In the spring of 1864 she was elected to the executive committee of the

Mother and daughter Jacobs continued their relief work in Alexandria until after the victory of the Union. Convinced that the freedmen in Alexandria were able to care for themselves, they followed the call of the ''New England Freedmen's Aid Society'' for teachers to help instruct the freedmen in

Mother and daughter Jacobs continued their relief work in Alexandria until after the victory of the Union. Convinced that the freedmen in Alexandria were able to care for themselves, they followed the call of the ''New England Freedmen's Aid Society'' for teachers to help instruct the freedmen in

After her return from England, Jacobs retired to private life. In

After her return from England, Jacobs retired to private life. In

Works by Harriet Jacobs

at DocSouth including her first published text, some of her reports from her work with fugitives, and ''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl''

''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl''.

Critical edition ed. Julie R. Adams, with introduction and resources for teachers and students. American Studies at the University of Virginia.

Short biography by Friends of Mount Auburn, including pictures of the tombstones of Harriet, John and Louisa Jacobs

listed by Donna Campbell, Professor at Washington State University

Selected Writings and Correspondence: Harriet Jacobs.

Collection of documents and resource guide from Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition,

Video of a 2013 lecture by Jean Fagan Yellin on Harriet Jacobs

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jacobs, Harriet 1813 births 1897 deaths 19th-century African-American people 19th-century American slaves 19th-century American women writers Activists from North Carolina African-American abolitionists African-American women writers African Americans in the American Civil War Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Burials in Massachusetts Christian abolitionists Literate American slaves People from Edenton, North Carolina People who wrote slave narratives 19th-century African-American women 19th-century African-American writers American women slaves

African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

writer whose autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

, ''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself'' is an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs, a mother and fugitive slave, published in 1861 by L. Maria Child, who edited the book for its author. Jacobs used the pseudonym Linda Brent. The ...

'', published in 1861 under the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

Linda Brent, is now considered an "American classic". Born into slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in Edenton, North Carolina

Edenton is a town in, and the county seat of, Chowan County, North Carolina, United States, on Albemarle Sound. The population was 4,397 at the 2020 census. Edenton is located in North Carolina's Inner Banks region. In recent years Edenton has b ...

, she was sexually harassed by her enslaver. When he threatened to sell her children if she did not submit to his desire, she hid in a tiny crawl space under the roof of her grandmother's house, so low she could not stand up in it. After staying there for seven years, she finally managed to escape to the free North, where she was reunited with her children Joseph and Louisa Matilda and her brother John S. Jacobs

John S. Jacobs (1815 or 1817 – December 19, 1873) was an African-American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. After escaping from Slavery in the United States, slavery he published his autobiography entitled ''A True Ta ...

. She found work as a nanny and got into contact with abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

reformers. Even in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, her freedom was in danger until her employer was able to pay off her legal owner.

During and immediately after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, she went to the Union-occupied parts of the South together with her daughter, organizing help and founding two schools for fugitive and freed slaves.

Biography

Family and name

Harriet Jacobs was born in 1813 inEdenton, North Carolina

Edenton is a town in, and the county seat of, Chowan County, North Carolina, United States, on Albemarle Sound. The population was 4,397 at the 2020 census. Edenton is located in North Carolina's Inner Banks region. In recent years Edenton has b ...

, to Delilah Horniblow, enslaved by the Horniblow family who owned a local tavern. Under the principle of ''partus sequitur ventrem

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The ...

'', both Harriet and her brother John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

were enslaved at birth by the tavern keeper's family, as a mother's status was passed to her children. Still, according to the same principle, mother and children should have been free, because Molly Horniblow, Delilah's mother, had been freed by her white father, who also was her owner. But she had been kidnapped, and had no chance for legal protection because of her dark skin. Harriet and John's father was Elijah Knox, also enslaved, but enjoying some privileges due to his skill as an expert carpenter. He died in 1826.

While Harriet's mother and grandmother were known by their owner's family name of Horniblow, Harriet used the opportunity of the baptism of her children to register Jacobs as their family name. She and her brother John also used that name after having escaped from slavery. The baptism was conducted without the knowledge of Harriet's master, Dr. Norcom. Harriet was convinced that her father should have been called Jacobs because his father was Henry Jacobs, a free white man. After Harriet's mother died, her father married a free African American. The only child from that marriage, Harriet's half brother, was called Elijah after his father and always used Knox as his family name, which was the name of his father's enslaver.

Early life in slavery

When Jacobs was six years old, her mother died. She then lived with her owner, a daughter of the deceased tavern keeper, who taught her not only to sew, but also to read and write. Only very few slaves were literate, although it was only in 1830 that North Carolina explicitly outlawed teaching slaves to read or write. Although Harriet's brother John succeeded in teaching himself to read, Jacobs, ''Incidents''br>94

When Jacobs was six years old, her mother died. She then lived with her owner, a daughter of the deceased tavern keeper, who taught her not only to sew, but also to read and write. Only very few slaves were literate, although it was only in 1830 that North Carolina explicitly outlawed teaching slaves to read or write. Although Harriet's brother John succeeded in teaching himself to read, Jacobs, ''Incidents''br>94/ref> he still wasn't able to write when he escaped from slavery as a young adult. J.Jacobs, ''Tale''br>126

/ref> In 1825, the owner of Harriet and John Jacobs died. She willed Harriet to her three-year-old niece Mary Matilda Norcom. Mary Matilda's father, the physician Dr. James Norcom (son-in-law of the deceased tavern keeper), became her ''de facto'' master. Her brother John and most of her other property was inherited by the tavern keeper's widow. Dr. Norcom hired John, so that the Jacobs siblings lived together in his household. Following the death of the widow, her slaves were sold at the New Year's Day auction, 1828. Among them were Harriet's brother John, her grandmother Molly Horniblow and Molly's son Mark. Being sold at public auction was a traumatic experience for twelve-year old John. Friends of hers bought Molly Horniblow and Mark with money Molly had been working hard to save over the many years of her servitude at the tavern. Afterwards Molly Horniblow was set free, and her own son Mark became her slave. Because of legal restrictions on

manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

, Mark had to remain his mother's slave until in 1847/48 she finally succeeded in getting him freed. John Jacobs was bought by Dr. Norcom, thus he and his sister stayed together.

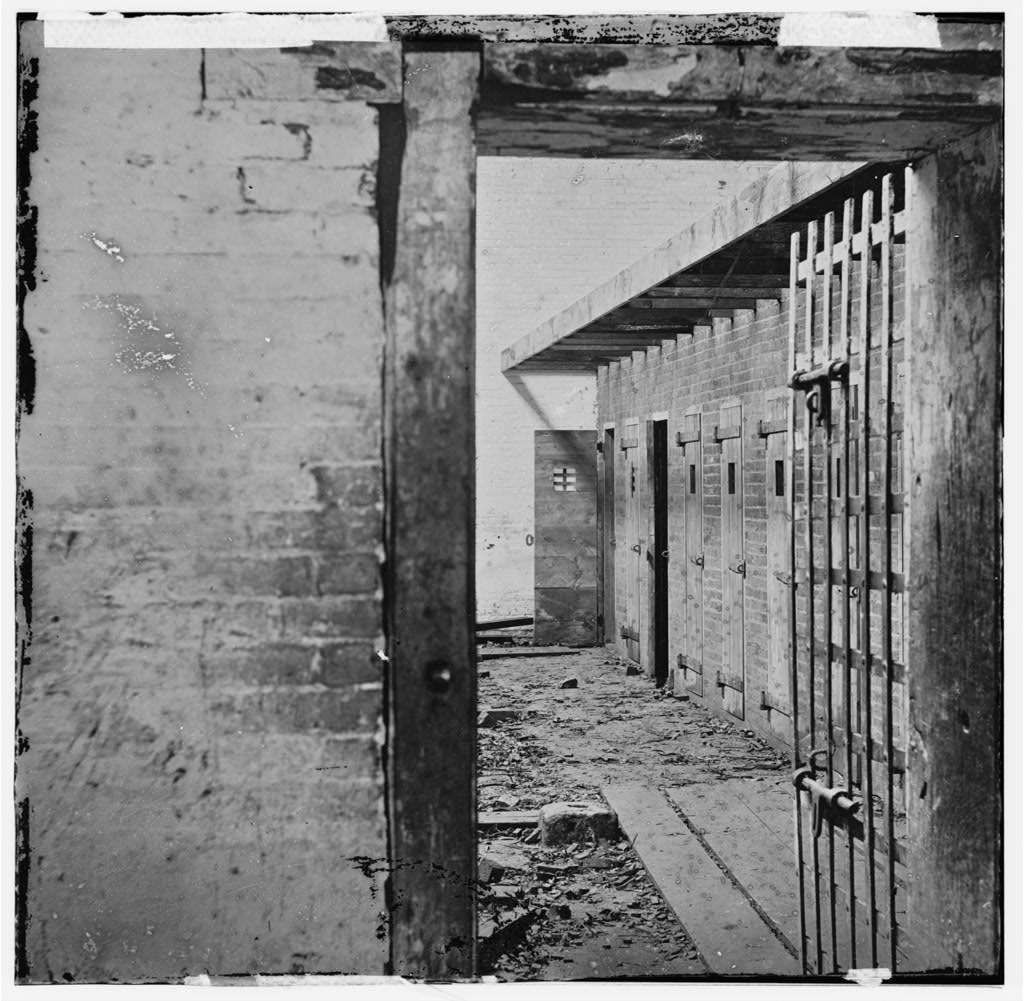

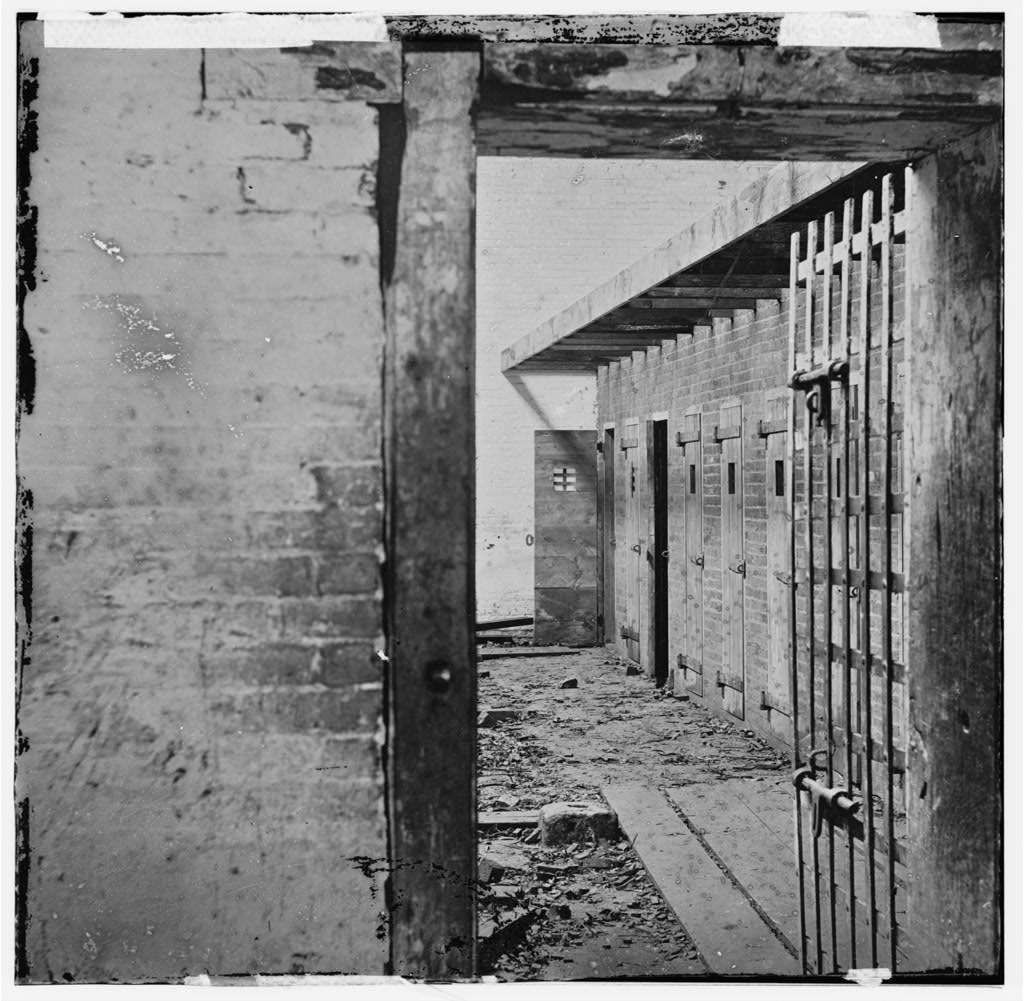

The same year, 1828, Molly Horniblow's youngest son, Joseph, tried to escape. He was caught, paraded in chains through Edenton, put into jail, and finally sold to New Orleans. The family later learned that he escaped again and reached New York. After that he was lost to the family. The Jacobs siblings who even as children were talking about escaping to freedom, saw him as a hero. Both of them would later name their sons for him.

Coping with sexual harassment

Norcom soon started harassing Jacobs sexually, causing the jealousy of his wife. When Jacobs fell in love with a free black man who wanted to buy her freedom and marry her, Norcom intervened and forbade her to continue with the relationship. Hoping for protection from Norcom's harassment, Jacobs started a relationship with Samuel Sawyer, a white lawyer and member of North Carolina's white elite, who would some years later be elected to theHouse of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

. Sawyer became the father of Jacobs's only children, Joseph (born 1829/30) and Louisa Matilda (born 1832/33). When she learned of Jacobs's pregnancy, Mrs. Norcom forbade her to return to her house, which enabled Jacobs to live with her grandmother. Still, Norcom continued his harassment during his numerous visits there; the distance ''as the crow flies'' between the two houses was only .

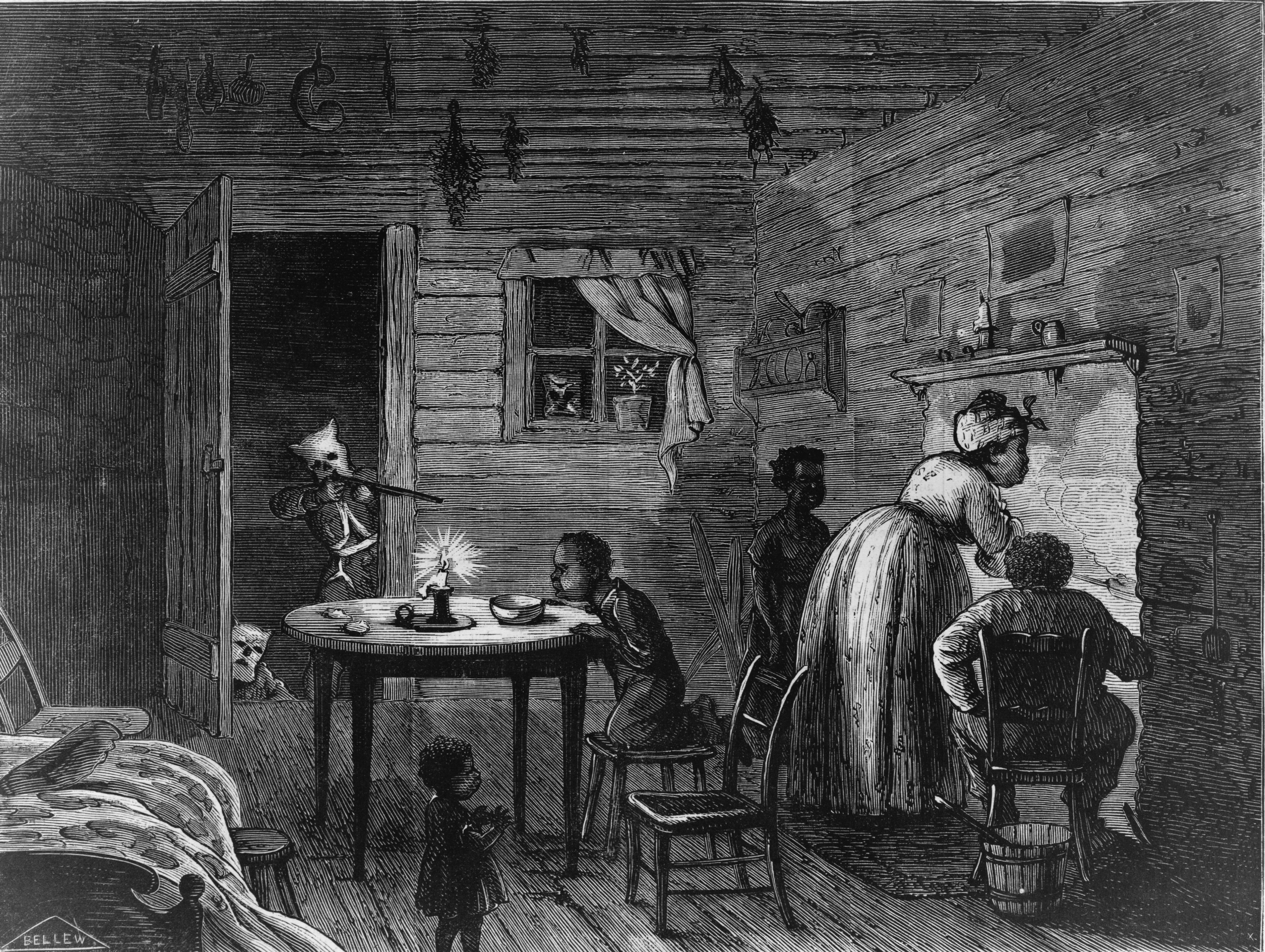

Seven years concealed

In April 1835, Norcom finally moved Jacobs from her grandmother's to the plantation of his son, some away. He also threatened to expose her children to the hard life of the plantation slaves and to sell them, separately and without the mother, after some time. In June 1835, Harriet Jacobs decided to escape. A white woman, who was a slaveholder herself, hid her at great personal risk in her house. After a short time, Jacobs had to hide in a swamp near the town, and at last she found refuge in a "tiny crawlspace" under the roof of her grandmother's house. The "garret" was only by and at its highest point. The impossibility of bodily exercise caused health problems which she still felt while writing her autobiography many years later. She bored a series of small holes into the wall, thus creating an opening approximately an inch square that allowed fresh air and some light to enter and that allowed her to see out. The light was barely sufficient to sew and to read the Bible and newspapers. Norcom reacted by selling her children and her brother John to a slave trader demanding that they should be sold in a different state, thus expecting to separate them forever from their mother and sister. However, the trader was secretly in league with Sawyer, to whom he sold all three of them, thus frustrating Norcom's plan on revenge. In her autobiography, Jacobs accuses Sawyer of not having kept his promise to legally manumit their children. Still, Sawyer allowed his enslaved children to live with their great-grandmother Molly Horniblow. After Sawyer married in 1838, Jacobs asked her grandmother to remind him of his promise. He asked and obtained Jacobs's approval to send their daughter to live with his cousin in Brooklyn, New York, where slavery had already been abolished. He also suggested to send their son to the Free States. While locked in her cell, Jacobs could often observe her unsuspecting children.

Norcom reacted by selling her children and her brother John to a slave trader demanding that they should be sold in a different state, thus expecting to separate them forever from their mother and sister. However, the trader was secretly in league with Sawyer, to whom he sold all three of them, thus frustrating Norcom's plan on revenge. In her autobiography, Jacobs accuses Sawyer of not having kept his promise to legally manumit their children. Still, Sawyer allowed his enslaved children to live with their great-grandmother Molly Horniblow. After Sawyer married in 1838, Jacobs asked her grandmother to remind him of his promise. He asked and obtained Jacobs's approval to send their daughter to live with his cousin in Brooklyn, New York, where slavery had already been abolished. He also suggested to send their son to the Free States. While locked in her cell, Jacobs could often observe her unsuspecting children.

Escape and freedom

In 1842, Jacobs finally got a chance to escape by boat toPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, where she was aided by anti-slavery activists of the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee

The Vigilant Association of Philadelphia was an abolitionist organization founded in August 1837 in Philadelphia to "create a fund to aid colored persons in distress". The initial impetus came from Robert Purvis, who had served on a previous '' ...

. After a short stay, she continued to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Although she had no references, Mary Stace Willis, the wife of the then extremely popular author Nathaniel Parker Willis

Nathaniel Parker Willis (January 20, 1806 – January 20, 1867), also known as N. P. Willis,Baker, 3 was an American author, poet and editor who worked with several notable American writers including Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfello ...

, accepted to hire Jacobs as the nanny of her baby daughter Imogen. The two women agreed on a trial period of one week, not suspecting that the relationship between the two families would last into the next generation, until the death of Louisa Matilda Jacobs at the home of Edith Willis Grinnell, the daughter of Nathaniel Willis and his second wife, in 1917.

In 1843 Jacobs heard that Norcom was on his way to New York to force her back into slavery, which was legal for him to do everywhere inside the United States. She asked Mary Willis for a leave of two weeks and went to her brother John in

In 1843 Jacobs heard that Norcom was on his way to New York to force her back into slavery, which was legal for him to do everywhere inside the United States. She asked Mary Willis for a leave of two weeks and went to her brother John in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. John Jacobs, in his capacity as personal servant, had accompanied his owner Sawyer on his marriage trip through the North in 1838. He had gained his freedom by leaving his master in New York. After that he had gone whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

and had been absent for more than three years. From Boston, Harriet Jacobs wrote to her grandmother asking her to send Joseph there, so that he could live there with his uncle John. After Joseph's arrival, she returned to her work as Imogen Willis's nanny.

Her work with the Willis family came to an abrupt end in October 1843, when Jacobs learned that her whereabouts had been betrayed to Norcom. Again, she had to flee to Boston, where the strength of the abolitionist movement

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

guaranteed a certain level of security. Moving to Boston also gave her the opportunity to take her daughter Louisa Matilda from the house of Sawyer's cousin in Brooklyn, where she had been treated not much better than a slave.

In Boston Jacobs took on odd jobs. Her stay there was interrupted by the death of Mary Stace Willis in March 1845. Nathaniel Willis took his daughter Imogen on a ten-month visit to the family of his deceased wife in England. For the journey, Jacobs resumed her job as nanny. In her autobiography, she reflects on the experiences made during the journey: She didn't notice any sign of racism, which often embittered her life in the USA. In consequence of this, she gained a new access to her Christian faith. At home, Christian ministers treating blacks with contempt or even buying and selling slaves had been an obstacle to her spiritual life.

The autobiography

Background: Abolitionism and early feminism

John S. Jacobs got more and more involved with abolitionism, i. e. the anti-slavery movement led by

John S. Jacobs got more and more involved with abolitionism, i. e. the anti-slavery movement led by William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

. He undertook several lecture tours, either alone or with fellow abolitionists, among them Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, three years his junior. In 1849, John S. Jacobs took responsibility for the ''Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room'' in Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

. His sister Harriet supported him, having been relieved of the daily care for her children (Joseph had left the Boston print shop where his mother had apprenticed him after suffering from racist abuse and had gone on a whaling voyage while his mother had been in England, and Louisa had been sent to a boarding school).

The former "slave girl" who had never been to school, and whose life had mostly been confined by the struggle for her own survival in dignity and that of her children, now found herself in circles that were about to change America through their - by the standards of the time - radical set of ideas. The ''Reading Room'' was in the same building as the newspaper '' The North Star'', run by Frederick Douglass, who today is considered the most influential African American of his century. Jacobs lived at the house of the white couple Amy and Isaac Post

Isaac and Amy Post, were radical Hicksite Quakers from Rochester, New York, and leaders in the nineteenth-century anti-slavery and women's rights movements. Among the first believers in Spiritualism, they helped to associate the young religious ...

. Douglass and the Posts were staunch enemies of slavery and racism, and supporters of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

. The year before, Douglass and Amy Post had attended the Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Methodist Church ...

, the world's first convention on women's rights, and had signed the Declaration of Sentiments

The Declaration of Sentiments, also known as the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, is a document signed in 1848 by 68 women and 32 men—100 out of some 300 attendees at the first women's rights convention to be organized by women. Held in Sen ...

, which demanded equal rights for women.

Obtaining legal freedom

In 1850, Jacobs paid a visit to Nathaniel Parker Willis in New York, wanting to see the now eight-years old Imogen again. Willis's second wife, Cornelia Grinnell Willis, who had not recovered well after the birth of her second child, prevailed upon Jacobs once again to become the nanny of the Willis children. Knowing that this involved a considerable risk for Jacobs, especially since theFugitive Slave Law of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most co ...

had made it much easier for slaveholders to reclaim their fugitive "chattels", she gave her word to John S. Jacobs that she would not let his sister fall into the hands of her persecutors.

In the spring of 1851, Jacobs was again informed that she was in danger of being recaptured. Cornelia Willis sent Jacobs together with her (Willis's) one-year-old daughter Lilian to Massachusetts which was comparatively safe. Jacobs, in whose autobiography the constant danger for herself and other enslaved mothers of being separated from their children is an important theme, spoke to her employer of the sacrifice that letting go of her baby daughter meant to her. Cornelia Willis answered by explaining that the slave catchers would have to return the baby to the mother, if Jacobs should be caught. She would then try to rescue Jacobs.

In February 1852, Jacobs read in the newspaper that her legal owner, the daughter of the recently deceased Dr. Norcom, had arrived at a New York Hotel together with her husband, obviously intending to re-claim their fugitive slave. Again, Cornelia Willis sent Jacobs to Massachusetts together with Lilian. Some days later, she wrote a letter to Jacobs informing her of her intention to buy Jacobs's freedom. Jacobs replied that she preferred to join her brother who had gone to California. Regardless, Cornelia Willis bought her freedom for $300. In her autobiography, Jacobs describes her mixed feelings: Bitterness at the thought that "a human being as''sold'' in the free city of New York", happiness at the thought that her freedom was secured, and "love" and "gratitude" for Cornelia Willis.

Obstacles: Trauma and shame

When Jacobs came to know the Posts in Rochester, they were the first white people she met since her return from England, who didn't look down on her color. Soon, she developed enough trust in Amy Post to be able to tell her her story which she had kept secret for so long. Post later described how difficult it was for Jacobs to tell of her traumatic experiences: "Though impelled by a natural craving for human sympathy, she passed through a baptism of suffering, even in recounting her trials to me. ... The burden of these memories lay heavily on her spirit".

In late 1852 or early 1853, Amy Post suggested that Jacobs should write her life story. Jacobs's brother had for some time been urging her to do so, and she felt a moral obligation to tell her story to help build public support for the antislavery cause and thus save others from suffering a similar fate.

Still, Jacobs had acted against moral ideas commonly shared in her time, including by herself, by consenting to a sexual relationship with Sawyer. The shame caused by this memory and the resulting fear of having to tell her story had been the reason for her initially avoiding contact with the abolitionist movement her brother John had joined in the 1840s. Finally, Jacobs overcame her trauma and feeling of shame, and she consented to publish her story. Her reply to Post describing her internal struggle has survived.

When Jacobs came to know the Posts in Rochester, they were the first white people she met since her return from England, who didn't look down on her color. Soon, she developed enough trust in Amy Post to be able to tell her her story which she had kept secret for so long. Post later described how difficult it was for Jacobs to tell of her traumatic experiences: "Though impelled by a natural craving for human sympathy, she passed through a baptism of suffering, even in recounting her trials to me. ... The burden of these memories lay heavily on her spirit".

In late 1852 or early 1853, Amy Post suggested that Jacobs should write her life story. Jacobs's brother had for some time been urging her to do so, and she felt a moral obligation to tell her story to help build public support for the antislavery cause and thus save others from suffering a similar fate.

Still, Jacobs had acted against moral ideas commonly shared in her time, including by herself, by consenting to a sexual relationship with Sawyer. The shame caused by this memory and the resulting fear of having to tell her story had been the reason for her initially avoiding contact with the abolitionist movement her brother John had joined in the 1840s. Finally, Jacobs overcame her trauma and feeling of shame, and she consented to publish her story. Her reply to Post describing her internal struggle has survived.

Writing of the manuscript

At first, Jacobs didn't feel that she was up to writing a book. She wrote a short outline of her story and asked Amy Post to send it toHarriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the harsh ...

, proposing to tell her story to Stowe so that Stowe could transform it into a book. Before Stowe's answer arrived, Jacobs read in the papers that the famous author, whose novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U. ...

'', published in 1852, had become an instant bestseller, was going to England. Jacobs then asked Cornelia Willis to propose to Stowe that Jacobs's daughter Louisa accompany her to England and tell the story during the journey. In reply, Stowe forwarded the story outline to Willis and declined to let Louisa join her, citing the possibility of Louisa being spoiled by too much sympathy shown to her in England. Jacobs felt betrayed because her employer thus came to know about the parentage of her children, which was the cause for Jacobs feeling ashamed. In a letter to Post, she analyzed the racist thinking behind Stowe's remark on Louisa with bitter irony: "what a pity we poor blacks can have the firmness and stability of character that you white people have." In consequence, Jacobs gave up the idea of enlisting Stowe's help.

In June 1853, Jacobs chanced to read a defense of slavery entitled "The Women of England vs. the Women of America" in an old newspaper. Written by

In June 1853, Jacobs chanced to read a defense of slavery entitled "The Women of England vs. the Women of America" in an old newspaper. Written by Julia Tyler

Julia Tyler ( ''née'' Gardiner; May 4, 1820 – July 10, 1889) was the second wife of John Tyler, who was the tenth president of the United States. As such, she served as the first lady of the United States from June 26, 1844, to March 4, 184 ...

, wife of former president John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president dire ...

, the text claimed that the household slaves were "well clothed and happy". Jacobs spent the whole night writing a reply, which she sent to the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

''. Her letter, signed "A Fugitive Slave", published on June 21, was her first text to be printed. Her biographer, Jean Fagan Yellin

Jean Fagan Yellin (September 19, 1930 – July 19, 2023) was an American historian specializing in women's history and African-American history, and Distinguished Professor Emerita of English at Pace University. She is best known for her scholars ...

, comments, "When the letter was printed ..., an author was born."

In October 1853, she wrote to Amy Post that she had decided to become the author of her own story. In the same letter, only a few lines earlier, she had informed Post of her grandmother's death. Yellin concludes that the "death of her revered grandmother" made it possible for Jacobs to "reveal her troubled sexual history" which she could never have done "while her proud, judgmental grandmother lived."

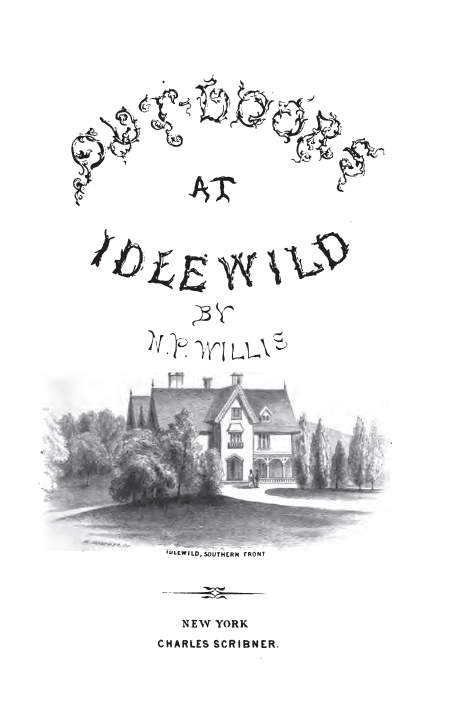

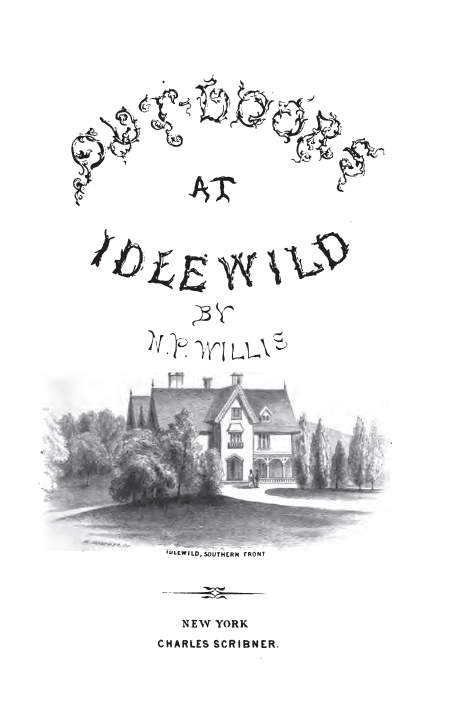

While using the little spare time a children's nurse had to write her story, Jacobs lived with the Willis family at Idlewild, their new country residence. With N.P.Willis being largely forgotten today, Yellin comments on the irony of the situation: "Idlewild had been conceived as a famous writer's retreat, but its owner never imagined that it was his children's nurse who would create an American classic there".

Louisa copied the manuscript, standardizing orthography and punctuation. Yellin observes that both style and content are "completely consistent" with the rest of Jacobs's writing and states, "there is no evidence to suggest that Louisa Matilda had any significant impact on either the subject matter or the style of the book."

When by mid-1857 her work was finally nearing completion, she asked Amy Post for a preface. Even in this letter she mentions the shame that made writing her story difficult for herself: "as much pleasure as it would afford me and as great an honor as I would deem it to have your name associated with my Book –Yet believe me dear friend there are many painful things in it – that make me shrink from asking the sacrifice from one so good and pure as your self–."

Searching for a publisher

In May 1858, Harriet Jacobs sailed to England, hoping to find a publisher there. She carried good letters of introduction, but wasn't able to get her manuscript into print. The reasons for her failure are not clear. Yellin supposes that her contacts among the British abolitionists feared that the story of her liaison with Sawyer would be too much for Victorian Britain's prudery. Disheartened, Jacobs returned to her work at Idlewild and made no further efforts to publish her book until the fall of 1859.

On October 16, 1859, the anti-slavery activist

In May 1858, Harriet Jacobs sailed to England, hoping to find a publisher there. She carried good letters of introduction, but wasn't able to get her manuscript into print. The reasons for her failure are not clear. Yellin supposes that her contacts among the British abolitionists feared that the story of her liaison with Sawyer would be too much for Victorian Britain's prudery. Disheartened, Jacobs returned to her work at Idlewild and made no further efforts to publish her book until the fall of 1859.

On October 16, 1859, the anti-slavery activist John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

tried to incite a slave rebellion at Harper's Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

. Brown, who was executed in December, was considered a martyr and hero by many abolitionists, among them Harriet Jacobs, who added a tribute to Brown as the final chapter to her manuscript. She then sent the manuscript to publishers Phillips and Samson in Boston. They were ready to publish it under the condition that either Nathaniel Parker Willis or Harriet Beecher Stowe would supply a preface. Jacobs was unwilling to ask Willis, who held pro-slavery views, but she asked Stowe, who declined. Soon after, the publishers failed, thus frustrating Jacobs's second attempt to get her story printed.

Lydia Maria Child as the book's editor

Jacobs now contactedThayer and Eldridge

Thayer & Eldridge (c.1860–1861) was a publishing firm in Boston, Massachusetts, established by William Wilde Thayer and Charles W. Eldridge. During its brief existence the firm issued works by James Redpath, Charles Sumner, and Walt Whitman, bef ...

, who had recently published a sympathizing biography of John Brown. Thayer and Eldridge demanded a preface by Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child ( Francis; February 11, 1802October 20, 1880) was an American abolitionist, women's rights activist, Native American rights activist, novelist, journalist, and opponent of American expansionism.

Her journals, both fiction and ...

. Jacobs confessed to Amy Post, that after suffering another rejection from Stowe, she could hardly bring herself to asking another famous writer, but she "resolved to make my last effort".

Jacobs met Child in Boston, and Child not only agreed to write a preface, but also to become the editor of the book. Child then re-arranged the material according to a more chronological order. She also suggested dropping the final chapter on Brown and adding more information on the anti-black violence which occurred in Edenton after Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion. She kept contact with Jacobs via mail, but the two women failed to meet a second time during the editing process, because with Cornelia Willis passing through a dangerous pregnancy and premature birth Jacobs was not able to leave Idlewild.

After the book had been stereotyped

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example ...

, Thayer and Eldridge, too, failed. Jacobs succeeded in buying the stereotype plates and to get the book printed and bound.

In January 1861, nearly four years after she had finished the manuscript, Jacobs's ''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl'' finally appeared before the public. The next month, her brother John S. published his own, much shorter memoir, entitled ''A True Tale of Slavery'', in London. Both siblings relate in their respective narratives their own experiences, experiences made together, and episodes in the life of the other sibling.

In her book, Harriet Jacobs doesn't mention the town or even the state, where she was held as a slave, and changes all personal names, given names as well as family names, with the only exception of the Post couple, whose names are given correctly. However, John Jacobs (called "William" in his sister's book) mentions Edenton as his birthplace and uses the correct given names, but abbreviates most family names. So Dr. Norcom is "Dr. Flint" in Harriet's book, but "Dr. N-" in John's. An author's name is not given on the title page, but the "Preface by the author" is signed "Linda Brent" and the narrator is called by that name throughout the story.

Reception of the book

The book was promoted via the abolitionist networks and was well received by the critics. Jacobs arranged for a publication in Great Britain, which was published in the first months of 1862, soon followed by a pirated edition. The publication did not cause contempt as Jacobs had feared. On the contrary, Jacobs gained respect. Although she had used a pseudonym, in abolitionist circles she was regularly introduced with words like "Mrs. Jacobs, the author of Linda", thereby conceding her the honorific "Mrs." which normally was reserved for married women. The ''London Daily News

The ''London Daily News'' was a short-lived London newspaper owned by Robert Maxwell. It was published from 24 February to 23 July 1987.

History

The ''London Daily News'' was intended to be a "24-hour" paper challenging the local dominance of t ...

'' wrote in 1862, that Linda Brent was a true "heroine", giving an example "of endurance and persistency in the struggle for liberty" and "moral rectitude".

Civil War and Reconstruction

Relief work and politics

After the

After the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

of president Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

in November 1860, the slavery question caused first the secession of most slave states and then the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. Thousands of African Americans, having escaped from slavery in the South, gathered just north of the front. Since Lincoln's administration continued to regard them as their masters' property, these refugees were in most cases declared "contraband of war" and simply called "Contrabands

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

". Many of them found refuge in makeshift camps, suffering and dying from want of the most basic necessities. Originally, Jacobs had planned to follow the example her brother John S. had set nearly two decades ago and become an abolitionist speaker, but now she saw that helping the ''Contrabands'' would mean rendering her race a service more urgently needed.

In the spring of 1862, Harriet Jacobs went to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

and neighboring Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in the northern region of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Downto ...

. She summarized her experiences during the first months in a report entitled ''Life among the Contrabands'', published in September in Garrison's ''The Liberator

Liberator or The Liberators or ''variation'', may refer to:

Literature

* ''Liberators'' (novel), a 2009 novel by James Wesley Rawles

* ''The Liberators'' (Suvorov book), a 1981 book by Victor Suvorov

* ''The Liberators'' (comic book), a Britis ...

''. The author was featured as "Mrs. Jacobs, the author of 'Linda'". This report is a description of the fugitives' misery designed to appeal to donors, but it is also a political denunciation of slavery. Jacobs emphasizes her conviction that the freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

will be able to build self-determined lives, if they get the necessary support.

During the fall of 1862, she traveled through the North using her popularity as author of ''Incidents'' to build up a network to support her relief work. The ''New York Friends'' (i.e. the Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

) gave her credentials as a relief agent.

From January 1863, she made Alexandria the center of her activity. Together with Quaker Julia Wilbur, the teacher, feminist and abolitionist, whom she had already known in Rochester, she was distributing clothes and blankets and at the same time struggling with incompetent, corrupt, or openly racist authorities.

While doing relief work in Alexandria, Jacobs was also involved in the political world. In May 1863 she attended the yearly conference of the New England Anti-Slavery Society in Boston. Together with the other participants she watched the parade of the newly created 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The unit was the second African-American regiment, following the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry ...

, consisting of black soldiers led by white officers. Since the Lincoln administration had declined to use African American soldiers only a few months past, this was a highly symbolic event. Jacobs expressed her joy and pride in a letter to Lydia Maria Child: "How my heart swelled with the thought that my poor oppressed race were to strike a blow for freedom !"

The Jacobs School

In most slave states, teaching slaves to read and write had been forbidden. Virginia had even prohibited teaching these skills to free blacks. After Union troops occupied Alexandria in 1861, some schools for blacks emerged, but there was not a single free school under African American control. Jacobs supported a project conceived by the black community in 1863 to found a new school. In the fall of 1863 her daughter Louisa Matilda who had been trained as a teacher, came to Alexandria in the company of Virginia Lawton, a black friend of the Jacobs family. After some struggle with white missionaries from the North who wanted to take control of the school, the ''Jacobs School'' opened in January 1864 under Louisa Matilda's leadership. In the ''National Anti-Slavery Standard'', Harriet Jacobs explained that it was not disapproval of white teachers that made her fight for the school being controlled by the black community. But she wanted to help the former slaves, who had been raised "to look upon the white race as their natural superiors and masters", to develop "respect for their race".

Jacobs's work in Alexandria was recognized on the local as well as on the national level, especially in abolitionist circles. In the spring of 1864 she was elected to the executive committee of the

In most slave states, teaching slaves to read and write had been forbidden. Virginia had even prohibited teaching these skills to free blacks. After Union troops occupied Alexandria in 1861, some schools for blacks emerged, but there was not a single free school under African American control. Jacobs supported a project conceived by the black community in 1863 to found a new school. In the fall of 1863 her daughter Louisa Matilda who had been trained as a teacher, came to Alexandria in the company of Virginia Lawton, a black friend of the Jacobs family. After some struggle with white missionaries from the North who wanted to take control of the school, the ''Jacobs School'' opened in January 1864 under Louisa Matilda's leadership. In the ''National Anti-Slavery Standard'', Harriet Jacobs explained that it was not disapproval of white teachers that made her fight for the school being controlled by the black community. But she wanted to help the former slaves, who had been raised "to look upon the white race as their natural superiors and masters", to develop "respect for their race".

Jacobs's work in Alexandria was recognized on the local as well as on the national level, especially in abolitionist circles. In the spring of 1864 she was elected to the executive committee of the Women's Loyal National League

The Women's Loyal National League, also known as the Woman's National Loyal League and other variations of that name, was formed on May 14, 1863, to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. It was organized b ...

, a women's organization founded in 1863 in response to an appeal by Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to so ...

which aimed at collecting signatures for a constitutional amendment

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, t ...

to abolish slavery. On August 1, 1864, she delivered the speech on occasion of the celebration of the British West Indian Emancipation in front of the African American soldiers of a military hospital in Alexandria. Many abolitionists, among them Frederick Douglass, stopped over in Alexandria while touring the South in order to see Jacobs and her work. On a personal level, she found her labors highly rewarding. Already in December 1862 she had written to Amy Post that the preceding six months had been the happiest in her whole life.

Relief work with freedmen in Savannah

Mother and daughter Jacobs continued their relief work in Alexandria until after the victory of the Union. Convinced that the freedmen in Alexandria were able to care for themselves, they followed the call of the ''New England Freedmen's Aid Society'' for teachers to help instruct the freedmen in

Mother and daughter Jacobs continued their relief work in Alexandria until after the victory of the Union. Convinced that the freedmen in Alexandria were able to care for themselves, they followed the call of the ''New England Freedmen's Aid Society'' for teachers to help instruct the freedmen in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. They arrived in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

in November 1865, only 11 months after the slaves there had been freed by Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, major ...

. During the following months they distributed clothes, opened a school and were planning to start an orphanage and an asylum for old people.

But the political situation had changed: Lincoln had been assassinated and his successor Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

was a Southerner and former slaveholder. He ordered the removal of many freedmen from the land which had been allotted to them by the army just one year before. The land question together with the unjust labor contracts forced on the former slaves by their former enslavers with the help of the army, are an important subject in Jacobs's reports from Georgia.

Already in July 1866, mother and daughter Jacobs left Savannah which was more and more suffering from anti-black violence. Once again, Harriet Jacobs went to Idlewild, to assist Cornelia Willis in caring for her dying husband until his death in January 1867.

In the spring of 1867, she visited the widow of her uncle Mark who was the only survivor of the family still living in Edenton. At the end of the year she undertook her last journey to Great Britain in order to collect money for the projected orphanage and asylum in Savannah. But after her return she had to realize that the anti-black terror in Georgia by the Ku-Klux-Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

and other groups rendered these projects impossible. The money collected was given to the asylum fund of the ''New York Friends''.

In the 1860s a personal tragedy occurred: In the early 1850s, her son Joseph had gone to California to search for gold together with his uncle John. Later the two had continued on to Australia. John S. Jacobs later went to England, while Joseph stayed in Australia. Some time later, no more letters reached Jacobs from Australia. Using her connections to Australian clergymen, Child had an appeal on behalf of her friend read in Australian churches, but to no avail. Jacobs never again heard of her son.

Later years and death

After her return from England, Jacobs retired to private life. In

After her return from England, Jacobs retired to private life. In Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, she kept a boarding house together with her daughter. Among her boarders were faculty members of nearby Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. In 1873, her brother John S. returned to the U.S. together with his English wife, their son Joseph and two stepchildren to live close to his sister in Cambridge. He died in December of the same year, 1873. In 1877 Harriet and Louisa Jacobs moved to Washington, D.C., where Louisa hoped to get work as a teacher. However, she found work only for short periods. Mother and daughter again took to keeping a boarding house, until in 1887/88 Harriet Jacobs became too sick to continue with the boarding house. Mother and daughter took on odd jobs and were supported by friends, among them Cornelia Willis. Harriet Jacobs died on March 7, 1897, in Washington, D.C., and was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery

Mount Auburn Cemetery is the first rural cemetery, rural, or garden, cemetery in the United States, located on the line between Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cambridge and Watertown, Massachusetts, Watertown in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Middl ...

in Cambridge next to her brother. Her tombstone reads, "Patient in tribulation, fervent in spirit serving the Lord". (Cf. Epistle to the Romans

The Epistle to the Romans is the sixth book in the New Testament, and the longest of the thirteen Pauline epistles. Biblical scholars agree that it was composed by Paul the Apostle to explain that salvation is offered through the gospel of J ...

, 12:11–12)

Legacy

Prior toJean Fagan Yellin

Jean Fagan Yellin (September 19, 1930 – July 19, 2023) was an American historian specializing in women's history and African-American history, and Distinguished Professor Emerita of English at Pace University. She is best known for her scholars ...

's research in the 1980s, the accepted academic opinion, voiced by such historians as John Blassingame

John Wesley Blassingame (March 23, 1940 – February 13, 2000) was an American historian and pioneer in the study of slavery in the United States. He was the former chairman of the African-American studies program at Yale University.

Blassing ...

, was that ''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself'' is an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs, a mother and fugitive slave, published in 1861 by L. Maria Child, who edited the book for its author. Jacobs used the pseudonym Linda Brent. The ...

'' was a fictional novel written by Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child ( Francis; February 11, 1802October 20, 1880) was an American abolitionist, women's rights activist, Native American rights activist, novelist, journalist, and opponent of American expansionism.

Her journals, both fiction and ...

. However, Yellin found and used a variety of historical documents, including from the Amy Post

Amy Kirby Post (December 20, 1802 – January 29, 1889) was an activist who was central to several important social causes of the 19th century, including the abolition of slavery and women's rights. Post's upbringing in Quakerism shaped her belie ...

papers at the University of Rochester, state and local historical societies, and the Horniblow and Norcom papers at the North Carolina state archives, to establish both that Harriet Jacobs was the true author of ''Incidents,'' and that the narrative was her autobiography, not a work of fiction. Her edition of ''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl'' was published in 1987 with the endorsement of Professor John Blassingame.

In 2004, Yellin published an exhaustive biography (394 pages) entitled ''Harriet Jacobs: A Life''. Yellin also conceived of the idea of the Harriet Jacobs Papers Project. In 2000, an advisory board for the project was established, and after funding was awarded, the project began on a full-time basis in September 2002. Of the approximately 900 documents by, to, and about Harriet Jacobs, her brother John S. Jacobs, and her daughter Louisa Matilda Jacobs amassed by the Project, over 300 were published in 2008 in a two volume edition entitled ''The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers''.

Today, Jacobs is seen as an "icon of female resistance". David S. Reynolds

David S. Reynolds (born 1948) is an American literary critic, biographer, and historian who has written about American literature and culture. He is the author or editor of fifteen books, on the Civil War era—including figures such as Walt W ...

' review of Yellin's 2004 biography in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', states that ''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl'' "and ''Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

''Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass'' is an 1845 memoir and treatise on abolition written by famous orator and former slave Frederick Douglass during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts. It is generally held to be the most famous of a numbe ...

'' are commonly viewed as the two most important slave narratives."

In an interview, Colson Whitehead

Arch Colson Chipp Whitehead (born November 6, 1969) is an American novelist. He is the author of eight novels, including his 1999 debut work '' The Intuitionist''; '' The Underground Railroad'' (2016), for which he won the 2016 National Book Awa ...

, author of the best selling novel, '' The Underground Railroad'', published in 2016, said: "Harriet Jacobs is a big referent for the character of Cora", the heroine of the novel. Cora has to hide in a place in the attic of a house in Jacobs's native North Carolina, where like Jacobs she is not able to stand, but like her can observe the outside life through a hole that "had been carved from the inside, the work of a previous occupant" (p. 185).

In 2017 Jacobs was the subject of an episode of the Futility Closet Podcast

Futility Closet is a blog, podcast, and database started in 2005 by editorial manager and publishing journalist Greg Ross. As of February 2021 the database totaled over 11,000 items. They range over the fields of history, literature, language, ...

, where her experience living in a crawl space was compared with the wartime experience of Patrick Fowler

Trooper Patrick Fowler (died 1964, aged 90), from Dublin, was a member of a cavalry regiment of the British Army, the 11th Hussars (Prince Albert's Own) who served during World War I. During an advance, Fowler was cut off from his regiment, and af ...

.

According to a 2017 article in ''Forbes'' magazine, a 2013 translation of ''Incidents'' by Yuki Horikoshi became a bestseller in Japan.

At the end of her preface to the 2000 edition of ''Incidents'', Yellin writes,

Timeline: Harriet Jacobs, abolitionism and literature

See also

*African-American literature

African American literature is the body of literature produced in the United States by writers of African descent. It begins with the works of such late 18th-century writers as Phillis Wheatley. Before the high point of slave narratives, African-A ...

* Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa (), was a writer and abolitionist from, according to his memoir, the Eboe (Igbo) region of the Kingdom of Benin (today southern Nigeria). Enslaved as ...

* Mary Prince

Mary Prince (c. 1 October 1788 – after 1833) was a British abolitionist and autobiographer, born in Bermuda to a slave family of African descent. After being sold a number of times, and being moved around the Caribbean, she was brought to Engl ...

* Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup (born July 10, 1807-1808) was an American abolitionist and the primary author of the memoir ''Twelve Years a Slave''. A free-born African American from New York, he was the son of a freed slave and a free woman of color. A far ...

Notes and references

Notes

References

Bibliography

* . * . * . * . * . * . * . * .External links

* * * *Works by Harriet Jacobs

at DocSouth including her first published text, some of her reports from her work with fugitives, and ''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl''

''Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl''.

Critical edition ed. Julie R. Adams, with introduction and resources for teachers and students. American Studies at the University of Virginia.

Short biography by Friends of Mount Auburn, including pictures of the tombstones of Harriet, John and Louisa Jacobs

listed by Donna Campbell, Professor at Washington State University

Selected Writings and Correspondence: Harriet Jacobs.

Collection of documents and resource guide from Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition,

Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

Video of a 2013 lecture by Jean Fagan Yellin on Harriet Jacobs

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jacobs, Harriet 1813 births 1897 deaths 19th-century African-American people 19th-century American slaves 19th-century American women writers Activists from North Carolina African-American abolitionists African-American women writers African Americans in the American Civil War Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Burials in Massachusetts Christian abolitionists Literate American slaves People from Edenton, North Carolina People who wrote slave narratives 19th-century African-American women 19th-century African-American writers American women slaves