Harpoon Head 1 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A harpoon is a long

A harpoon is a long

In the 1990s, harpoon points, known as the

In the 1990s, harpoon points, known as the

(

The first use of explosives in the hunting of whales was made by the British

The first use of explosives in the hunting of whales was made by the British  Together with the steam-powered whale catcher, this development ushered in the modern age of commercial whaling. Euro-American whalers were now equipped to hunt faster and more powerful species, such as the

Together with the steam-powered whale catcher, this development ushered in the modern age of commercial whaling. Euro-American whalers were now equipped to hunt faster and more powerful species, such as the  The modern whaling harpoon consists of a deck-mounted launcher (mostly a cannon) and a projectile which is a large harpoon with an explosive (penthrite) charge, attached to a thick rope. The spearhead is shaped in a manner which allows it to penetrate the thick layers of whale blubber and stick in the flesh. It has sharp spikes to prevent the harpoon from sliding out. Thus, by pulling the rope with a motor, the whalers can drag the whale back to their ship.

A recent development in harpoon technology is the hand-held

The modern whaling harpoon consists of a deck-mounted launcher (mostly a cannon) and a projectile which is a large harpoon with an explosive (penthrite) charge, attached to a thick rope. The spearhead is shaped in a manner which allows it to penetrate the thick layers of whale blubber and stick in the flesh. It has sharp spikes to prevent the harpoon from sliding out. Thus, by pulling the rope with a motor, the whalers can drag the whale back to their ship.

A recent development in harpoon technology is the hand-held

Problems hit Philae after historic first comet landing

''

*

*

Whalecraft: Harpoons

{{Authority control Fishing equipment Personal weapons Projectile weapons Ancient weapons Inuit tools

A harpoon is a long

A harpoon is a long spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

-like instrument and tool used in fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

, whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

, sealing, and other marine hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

to catch and injure large fish or marine mammal

Marine mammals are aquatic mammals that rely on the ocean and other marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as seals, whales, manatees, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reli ...

s such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal and securing it with barb or toggling claws, allowing the fishermen to use a rope or chain attached to the projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found in ...

to catch the animal. A harpoon can also be used as a weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

. Certain harpoons are made with different builds to perform better with the type of target being aimed at. For example, the Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

have short, fixed foreshaft harpoons for hunting seals at their breathing holes while loose shafted ones are made for attaching to the game thrown at.

History

In the 1990s, harpoon points, known as the

In the 1990s, harpoon points, known as the Semliki harpoon The Semliki harpoon, also known as the Katanda harpoon, refers to a group of complex barbed harpoon heads carved from bone, which were found at an archaeologic site on the Semliki River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire); the a ...

s or the Katanda harpoons, were found in the Katanda Katanda may refer to:

* Katanda, Russia, a locality in the Altai Republic

*In the Democratic Republic of the Congo:

** Katanda Territory, an administrative division of Kasaï-Oriental province

*** Katanda, the town that is its administrative cente ...

region in Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

(called the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

today). As the earliest known harpoons, these weapons were made and used 90,000 years ago, most likely to spear catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Named for their prominent barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, catfish range in size and behavior from the three largest species alive, ...

es. Later, in Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, spearfishing

Spearfishing is a method of fishing that involves impaling the fish with a straight pointed object such as a spear, gig or harpoon. It has been deployed in artisanal fishing throughout the world for millennia. Early civilisations were familia ...

with poles (harpoons) was widespread in palaeolithic times, especially during the Solutrean

The Solutrean industry is a relatively advanced flint tool-making style of the Upper Paleolithic of the Final Gravettian, from around 22,000 to 17,000 BP. Solutrean sites have been found in modern-day France, Spain and Portugal.

Details

T ...

and Magdalenian

The Magdalenian cultures (also Madelenian; French: ''Magdalénien'') are later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic in western Europe. They date from around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. It is named after the type site of La Madele ...

periods. Cosquer Cave

The Cosquer Cave is located in the ''Calanque de Morgiou'' in Marseille, France, near Cap Morgiou. The entrance to the cave is located underwater, due to the Holocene sea level rise. The cave contains various prehistoric rock art engravings. Its ...

in Southern France contains cave art over 16,000 years old, including drawings of seals which appear to have been harpooned.

There are references to harpoons in ancient literature; though, in most cases, the descriptions do not go into detail. An early example can be found in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

in Job

Work or labor (or labour in British English) is intentional activity people perform to support the needs and wants of themselves, others, or a wider community. In the context of economics, work can be viewed as the human activity that contr ...

br>41:7(

NIV Niv may refer to:

* Niv, a personal name; for people with the name, see

* Niv Art Movies, a film production company of India

* Niv Art Centre, in New Delhi, India

NIV may refer to:

* The New International Version, a translation of the Bible into E ...

): "Can you fill its hide with harpoons or its head with fishing spears?" The Greek historian Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

(c. 203 BC – 120 BC), in his ''Histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), ...

'', describes hunting for swordfish by using a harpoon with a barbed and detachable head. Copper harpoons were known to the seafaring Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

ns well into antiquity. Early hunters in India include the Mincopie people, aboriginal inhabitants of India's Andaman and Nicobar

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands is a union territory of India consisting of 572 islands, of which 37 are inhabited, at the junction of the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. The territory is about north of Aceh in Indonesia and separated f ...

islands, who have used harpoons with long cords for fishing since early times.

Whaling

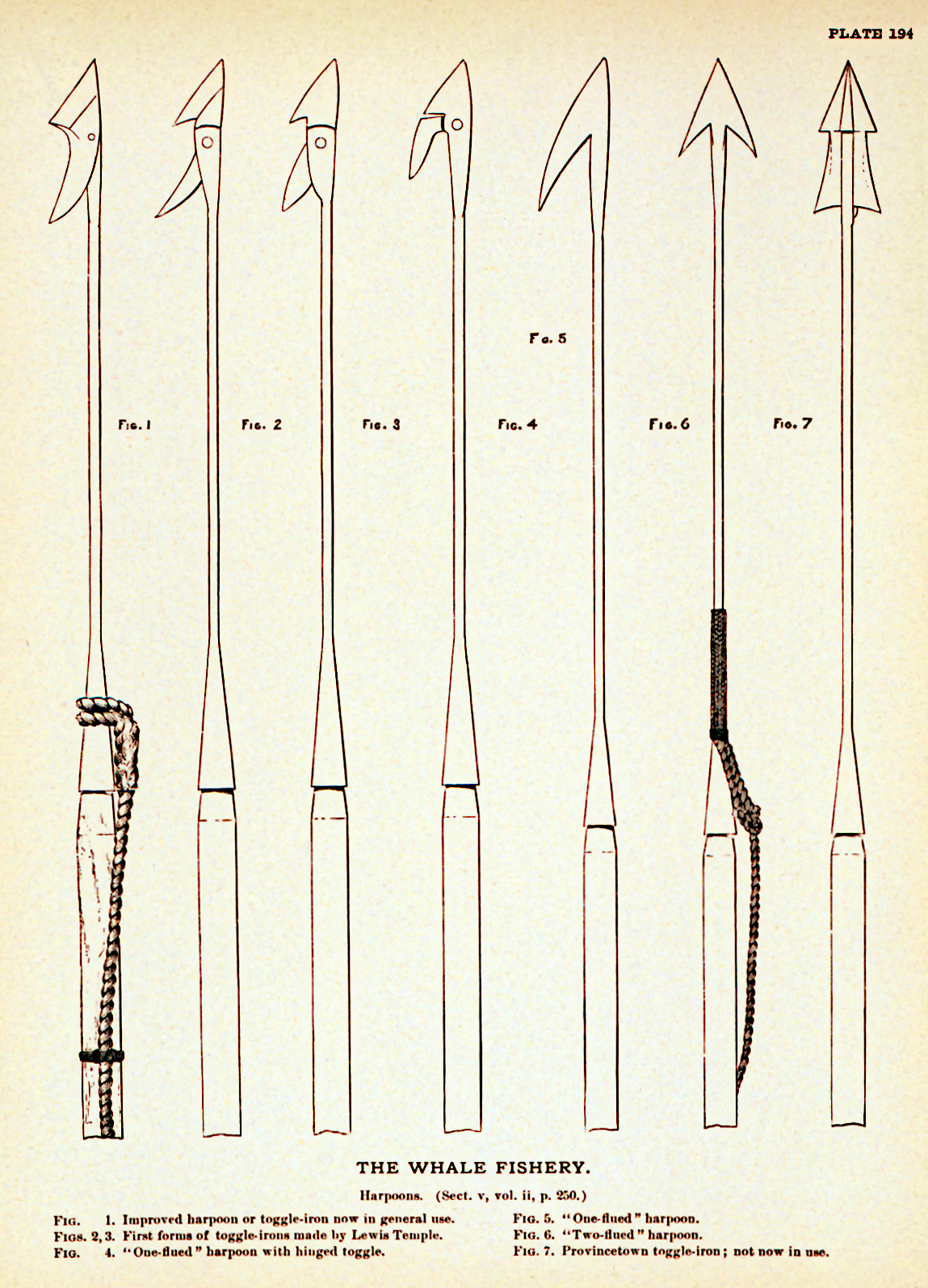

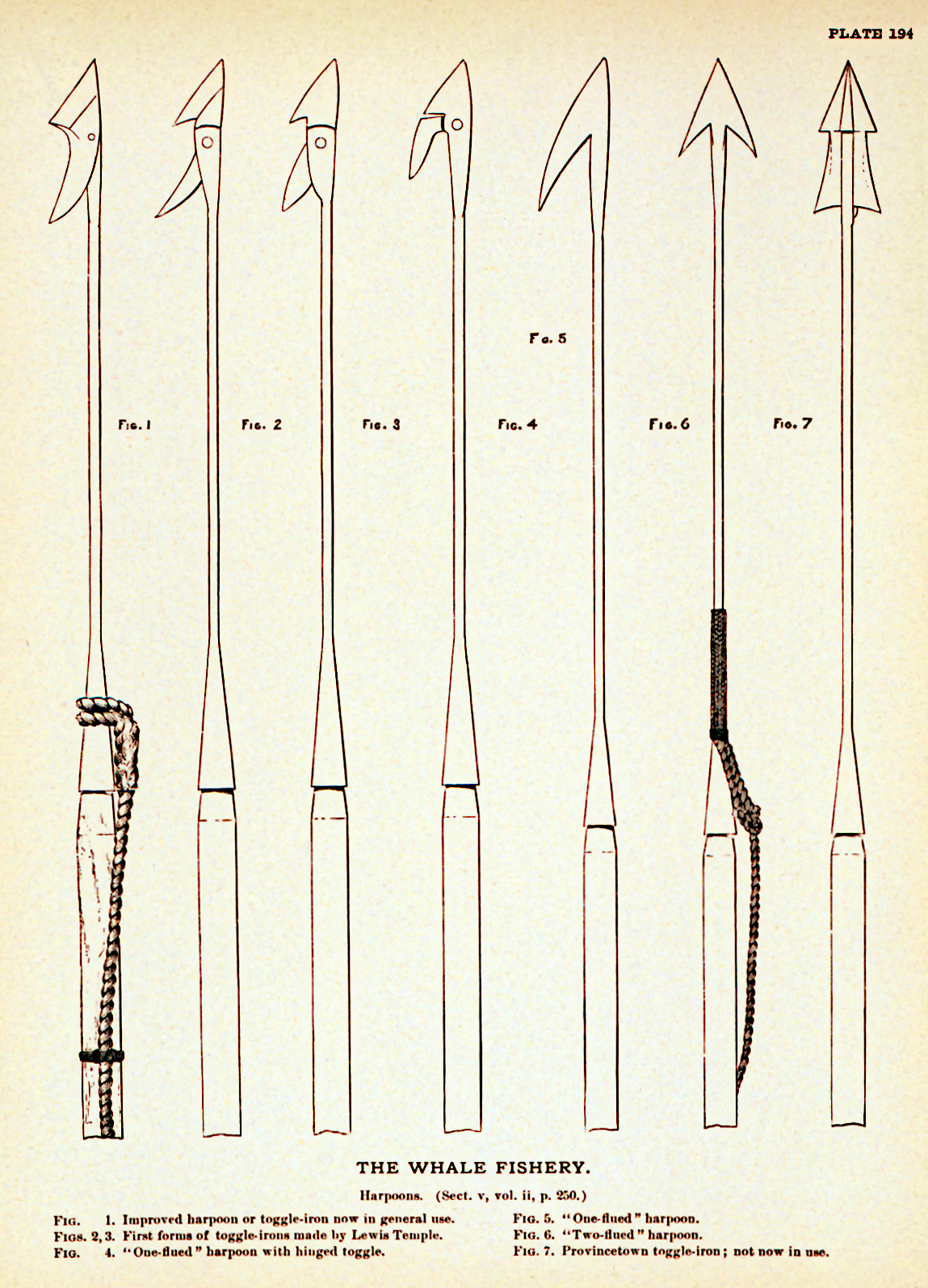

The two flue harpoon was the primary weapon used inwhaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

around the world, but it tended to penetrate no deeper than the soft outer layer of blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians.

Description

Lipid-rich, collagen fiber-laced blubber comprises the hypodermis and covers the whole body, except for pa ...

. Thus it was often possible for the whale to escape by struggling or swimming away forcefully enough to pull the shallowly embedded barbs out backwards. This flaw was corrected in the early nineteenth century with the creation of the one flue harpoon

{{no footnotes, date=February 2014

The one-flue harpoon or one-flue iron (sometimes "single" instead of "one" is used) is a type of harpoon used in whaling after its introduction in the early 19th century when it replaced the two-flue harpoon. Due ...

; by removing one of the flues, the head of the harpoon was narrowed, making it easier for it to penetrate deep enough to hold fast. In the Arctic, the indigenous people used the more advanced toggling harpoon

The toggling harpoon is an ancient weapon and tool used in whaling to impale a whale when thrown. Unlike earlier harpoon versions which had only one point, a toggling harpoon has a two-part point. One half of the point is firmly attached to the ...

design. In the mid-19th century, the toggling harpoon was adapted by Lewis Temple, using iron. The Temple toggle was widely used, and quickly came to dominate whaling.

In the novel ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael (Moby-Dick), Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Captain Ahab, Ahab, captain of the whaler, whaling ship ''Pequod (Moby- ...

'', Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

explained the reason for the harpoon's effectiveness:

He also describes another device that was at times a necessary addition to harpoons:

Explosive harpoons

The first use of explosives in the hunting of whales was made by the British

The first use of explosives in the hunting of whales was made by the British South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

in 1737, after some years of declining catches. A large fleet was sent, armed with cannon-fired harpoons. Although the weaponry was successful in killing the whales, most of the catch sank before being retrieved. However, the system was still occasionally used, and underwent successive improvements at the hands of various inventors over the next century, including Abraham Stagholt in the 1770s and George Manby

Captain George William Manby FRS (28 November 1765 – 18 November 1854) was an English author and inventor. He designed an apparatus for saving life from shipwrecks and also the first modern form of fire extinguisher.

Early life

Manby was bo ...

in the early 19th century.

William Congreve

William Congreve (24 January 1670 – 19 January 1729) was an English playwright and poet of the Restoration period. He is known for his clever, satirical dialogue and influence on the comedy of manners style of that period. He was also a min ...

, who invented some of the first rockets

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

for British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

use, designed a rocket-propelled whaling harpoon in the 1820s. The shell was designed to explode on contact and impale the whale with the harpoon. The weapon was in turn attached by a line to the boat, and the hope was that the explosion would generate enough gas within the whale to keep it afloat for retrieval. Expeditions were sent out to try this new technology; many whales were killed, but most of them sank. These early devices, called bomb lances, became widely used for the hunting of humpbacks and right whale

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus ''Eubalaena'': the North Atlantic right whale (''E. glacialis''), the North Pacific right whale (''E. japonica'') and the Southern right whale (''E. australis''). They are clas ...

s. A notable user of these early explosive harpoons was the American Thomas Welcome Roys

Thomas Welcome Roys (c. 1816 - d. 1877) was an American whaleman. He was significant in the history of whaling in that he discovered the Western Arctic bowhead whale population and developed and patented whaling rockets in order to hunt the faste ...

in 1865, who set up a shore station in Seydisfjördur, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

. A slump in oil prices after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

forced their endeavor into bankruptcy in 1867.

An early version of the explosive harpoon was designed by Jacob Nicolai Walsøe, a Norwegian painter and inventor. His 1851 application was rejected by the interior ministry on the grounds that he had received public funding for his experiments. In 1867, a Danish fireworks manufacturer, Gaetano Amici, patented a cannon-fired harpoon, and in the same year, an Englishman, George Welch, patented a grenade harpoon very similar to the version which transformed whaling in the following decade.

In 1870, the Norwegian shipping magnate Svend Foyn

Svend Foyn (July 9, 1809 – November 30, 1894) was a Norwegian whaling, shipping magnate and philanthropist. He pioneered revolutionary methods for hunting and processing whales. Svend Foyn introduced the modern harpoon cannon and brought ...

patented and pioneered the modern exploding whaling harpoon and gun. Foyn had studied the American method in Iceland. His basic design is still in use today. He perceived the failings of other methods and solved these problems in his own system. He included, with the help of H.M.T. Esmark, a grenade tip that exploded inside the whale. This harpoon design also utilized a shaft that was connected to the head with a moveable joint. His original cannons were muzzle-loaded with special padding and also used a unique form of gunpowder. The cannons were later replaced with safer breech-loading types.

Together with the steam-powered whale catcher, this development ushered in the modern age of commercial whaling. Euro-American whalers were now equipped to hunt faster and more powerful species, such as the

Together with the steam-powered whale catcher, this development ushered in the modern age of commercial whaling. Euro-American whalers were now equipped to hunt faster and more powerful species, such as the rorquals

Rorquals () are the largest group of baleen whales, which comprise the family Balaenopteridae, containing ten extant species in three genera. They include the largest animal that has ever lived, the blue whale, which can reach , and the fin whale ...

. Because rorquals sank when they died, later versions of the exploding harpoon injected air into the carcass to keep it afloat.

The modern whaling harpoon consists of a deck-mounted launcher (mostly a cannon) and a projectile which is a large harpoon with an explosive (penthrite) charge, attached to a thick rope. The spearhead is shaped in a manner which allows it to penetrate the thick layers of whale blubber and stick in the flesh. It has sharp spikes to prevent the harpoon from sliding out. Thus, by pulling the rope with a motor, the whalers can drag the whale back to their ship.

A recent development in harpoon technology is the hand-held

The modern whaling harpoon consists of a deck-mounted launcher (mostly a cannon) and a projectile which is a large harpoon with an explosive (penthrite) charge, attached to a thick rope. The spearhead is shaped in a manner which allows it to penetrate the thick layers of whale blubber and stick in the flesh. It has sharp spikes to prevent the harpoon from sliding out. Thus, by pulling the rope with a motor, the whalers can drag the whale back to their ship.

A recent development in harpoon technology is the hand-held speargun

A speargun is a ranged underwater fishing device designed to launch a tethered spear or harpoon to impale fish or other marine animals and targets. Spearguns are used in sport fishing and underwater target shooting. The two basic types are ''pne ...

. Divers use the speargun for spearing fish. They may also be used for defense against dangerous marine animals. Spearguns may be powered by pressurized gas

A compressed fluid (also called a compressed or unsaturated liquid, subcooled fluid or liquid) is a fluid under mechanical or thermodynamic conditions that force it to be a liquid.

At a given pressure, a fluid is a compressed fluid if it is at ...

or with mechanical means like springs or elastic bands.

Space

The Philae spacecraft carried harpoons for helping the probe anchor itself to the surface ofcomet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ar ...

67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko

67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (abbreviated as 67P or 67P/C–G) is a Jupiter-family comet, originally from the Kuiper belt, with a current orbital period of 6.45 years, a rotation period of approximately 12.4 hours and a maximum velocity of . Chu ...

. However, the harpoons failed to fire.Aron, Jacob.Problems hit Philae after historic first comet landing

''

New Scientist

''New Scientist'' is a magazine covering all aspects of science and technology. Based in London, it publishes weekly English-language editions in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. An editorially separate organisation publishe ...

''.

See also

Hawaiian sling

The Hawaiian sling is a device used in spearfishing. The sling operates much like a bow and arrow does on land, but energy is stored in rubber tubing rather than a wooden or fiberglass bow.

Description

Mechanically, the device is simple: the only ...

* Speargun

A speargun is a ranged underwater fishing device designed to launch a tethered spear or harpoon to impale fish or other marine animals and targets. Spearguns are used in sport fishing and underwater target shooting. The two basic types are ''pne ...

* Trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the God of the Sea in classical mythology. The trident may occasionally be held by other marine ...

* Kakivak

A kakivak is an Inuit leister that is used for spear fishing and fishing at the short range. It is comparable to a harpoon or a trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trid ...

Notes

References

*Lødingen Local History Society (1986) Yearbook Lødingen. The modern history of whaling, . *Lødingen local historical society (1999/2000) Yearbook Lødingen. More about Jacob Nicolai Walsøe, granatharpunens inventor, . * Information aboutErik Eriksen

Erik Eriksen (20 November 1902 – 7 October 1972) was a Denmark, Danish politician, who served as Prime Minister of Denmark from 1950 to 1953 and as the fourth President of the Nordic Council in 1956. Eriksen was leader of the Denmark, Dan ...

based on ''The Discovery of King Karl Land, Spitsbergen'', by Adolf Hoel

Adolf Hoel (15 May 1879 – 19 February 1964) was a Norwegian geologist, environmentalist and Polar region researcher. He led several scientific expeditions to Svalbard and Greenland. Hoel has been described as one of the most iconic and influentia ...

, '' The Geographical Review'' Vol. XXV, No. 3, July, 1935, Pp. 476–478, American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows from around the ...

, Broadway AT 156th Street, New York" and Store norske leksikon, Aschehoug & Gyldendal (Great Norwegian Encyclopedia, last edition)

* F.R. Allchin in ''South Asian Archaeology 1975: Papers from the Third International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, Held in Paris'' (December 1979) edited by J.E.van Lohuizen-de Leeuw. Brill Academic Publishers, Incorporated. Pages 106–118. .

* Edgerton; et al. (2002). ''Indian and Oriental Arms and Armour''. Courier Dover Publications. .

* Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2003). ''The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia''. Cambridge University Press. .

External links

Whalecraft: Harpoons

{{Authority control Fishing equipment Personal weapons Projectile weapons Ancient weapons Inuit tools