hamon (swordsmithing) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In swordsmithing, (from

In swordsmithing, (from

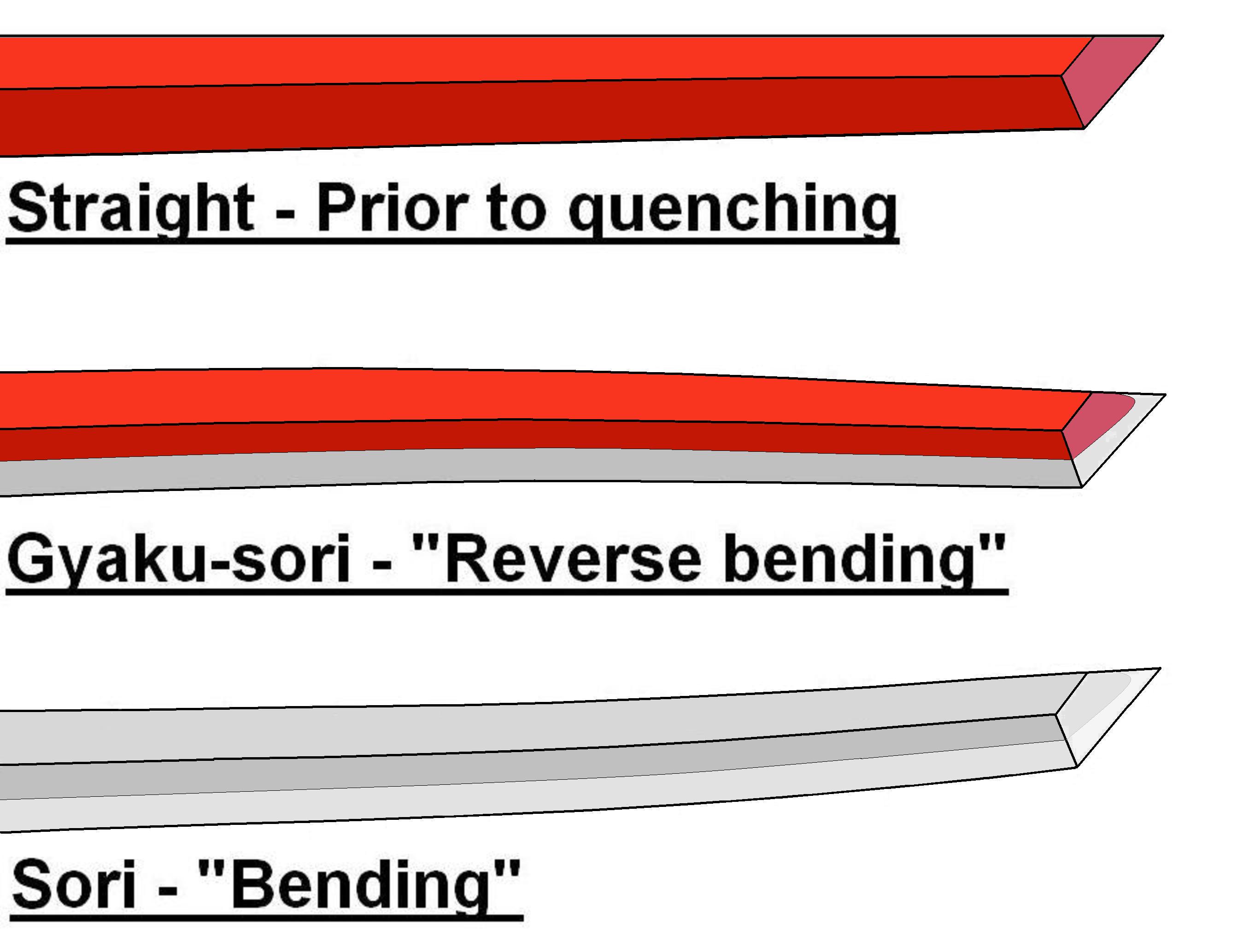

The hamon of a blade is created during the

The hamon of a blade is created during the

The shape of the hamon is affected by many factors, but is primarily controlled by the shape of the clay coating at the time of quenching. Although each school had its own methods of application, and kept secret the process, the exact mixture of the clay, the thickness of the coat, and even the temperature of the water, the clay was usually applied by painting it on in very thin layers, to help prevent shrinking, peeling, and cracking as it dried. Often, the clay is applied to the entire blade by piling up the layers very thickly over the entire sword, and then the clay was carefully cut away from the edge. However, in ancient times tempering was rarely used in Asia, and a fully exposed edge would cool too fast and become far too brittle, thus a thinner layer of clay was usually applied to the edge so as to achieve the correct hardness upon quenching without the need for tempering afterwards.

The smith shapes the hamon at the time of coating the blade. There are two basic styles, which are "straight edge" (''sugaha'') and "irregular pattern" (''midare'' or ''midareba''). Straight-edge hamons simply follow the edge of the sword with little deviation, except at the tip. This was by far the most popular style in every era and in every province, whereas the more complex patterns that were in themselves works of art tended to be reserved for the wealthy and elite. Straight patterns are usually classified by the width of the hardened zone (''yakiba''), and divided into "wide" (''hiro''), "medium" (''cho''), "narrow" (''hoso''), and extremely narrow or "string" (''ito'') hamons.

Conversely, irregular hamons do not simply follow the edge, but deviate from it considerably in various ways. The two main groups are "undulating" or "wavy" (''notare'') and tooth-like or "zig-zag" (''gunome''), and these are often classified by the

The shape of the hamon is affected by many factors, but is primarily controlled by the shape of the clay coating at the time of quenching. Although each school had its own methods of application, and kept secret the process, the exact mixture of the clay, the thickness of the coat, and even the temperature of the water, the clay was usually applied by painting it on in very thin layers, to help prevent shrinking, peeling, and cracking as it dried. Often, the clay is applied to the entire blade by piling up the layers very thickly over the entire sword, and then the clay was carefully cut away from the edge. However, in ancient times tempering was rarely used in Asia, and a fully exposed edge would cool too fast and become far too brittle, thus a thinner layer of clay was usually applied to the edge so as to achieve the correct hardness upon quenching without the need for tempering afterwards.

The smith shapes the hamon at the time of coating the blade. There are two basic styles, which are "straight edge" (''sugaha'') and "irregular pattern" (''midare'' or ''midareba''). Straight-edge hamons simply follow the edge of the sword with little deviation, except at the tip. This was by far the most popular style in every era and in every province, whereas the more complex patterns that were in themselves works of art tended to be reserved for the wealthy and elite. Straight patterns are usually classified by the width of the hardened zone (''yakiba''), and divided into "wide" (''hiro''), "medium" (''cho''), "narrow" (''hoso''), and extremely narrow or "string" (''ito'') hamons.

Conversely, irregular hamons do not simply follow the edge, but deviate from it considerably in various ways. The two main groups are "undulating" or "wavy" (''notare'') and tooth-like or "zig-zag" (''gunome''), and these are often classified by the

Many modern reproductions do not have natural hamon because they are thoroughly hardened monosteel; the appearance of a hamon is reproduced via various processes such as acid

Many modern reproductions do not have natural hamon because they are thoroughly hardened monosteel; the appearance of a hamon is reproduced via various processes such as acid

Cheness Inc page about Hamons and how to differentiate fakes

Japanese swords

In swordsmithing, (from

In swordsmithing, (from Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

, literally "edge pattern") is a visible effect created on the blade by the hardening process. The hamon is the outline of the hardened zone (''yakiba'') which contains the cutting edge (''ha''). Blades made in this manner are known as differentially hardened, with a harder cutting edge than spine (''mune'') (for example: spine 40 HRC vs edge 58 HRC). This difference in hardness results from clay being applied on the blade (''tsuchioki'') prior to the cooling process (quenching

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, such as pha ...

). Less or no clay allows the edge to cool faster, making it harder but more brittle, while more clay allows the center (''hira'') and spine to cool slower, thus retaining its resilience.''A History of Metallography'' By Cyril Stanley Smith -- MIT Press 1968 Page 40--57

Introduction

quenching

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, such as pha ...

process (''yakiire''). During the differential heat treatment

Differential heat treatment (also called selective heat treatment or local heat treatment) is a technique used during heat treating to harden or soften certain areas of a steel object, creating a difference in hardness between these areas. There ar ...

, the clay coating on the back of the sword reduces the cooling speed of the red-hot metal when it is plunged into the water and allows the steel to turn into pearlite, a soft structure consisting of cementite

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, brit ...

and ferrite (iron)

At atmospheric pressure, three allotropic forms of iron exist, depending on temperature: alpha iron (α-Fe), gamma iron (γ-Fe), and delta iron (δ-Fe). At very high pressure, a fourth form exists, called epsilon iron (ε-Fe). Some controvers ...

laminations. On the other hand, the exposed edge cools very rapidly, changing into a phase called martensite, which is nearly as hard and brittle as glass.

The hamon outlines the transition between the region of harder martensitic

Martensite is a very hard form of steel crystalline structure. It is named after German metallurgist Adolf Martens. By analogy the term can also refer to any crystal structure that is formed by diffusionless transformation.

Properties

Mart ...

steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

at the blade

A blade is the portion of a tool, weapon, or machine with an edge that is designed to puncture, chop, slice or scrape surfaces or materials. Blades are typically made from materials that are harder than those they are to be used on. Historic ...

's edge and the softer pearlitic

Pearlite is a two-phased, lamellar (or layered) structure composed of alternating layers of ferrite (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. During slow cooling of an iron-carbon alloy, pearlite form ...

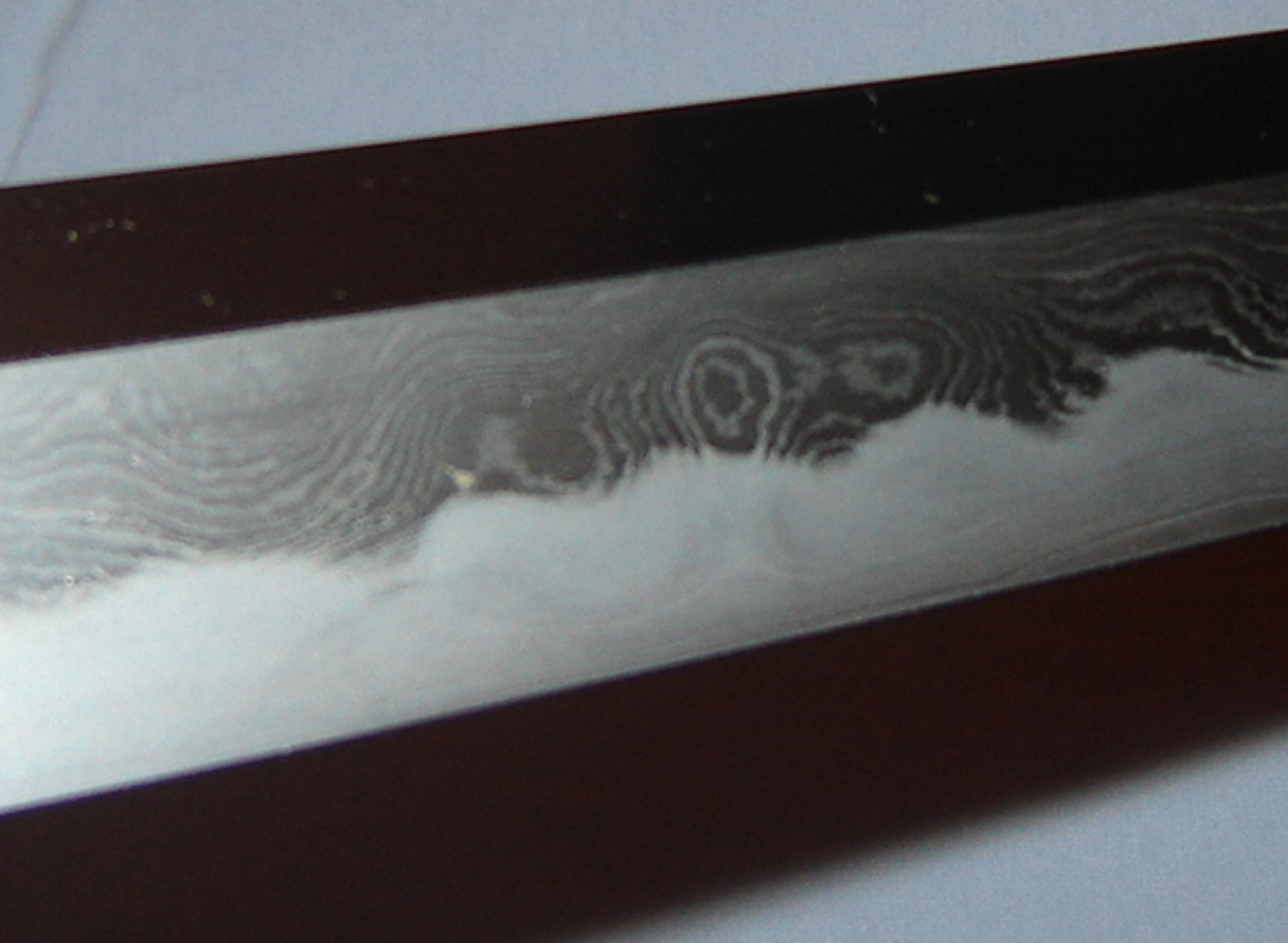

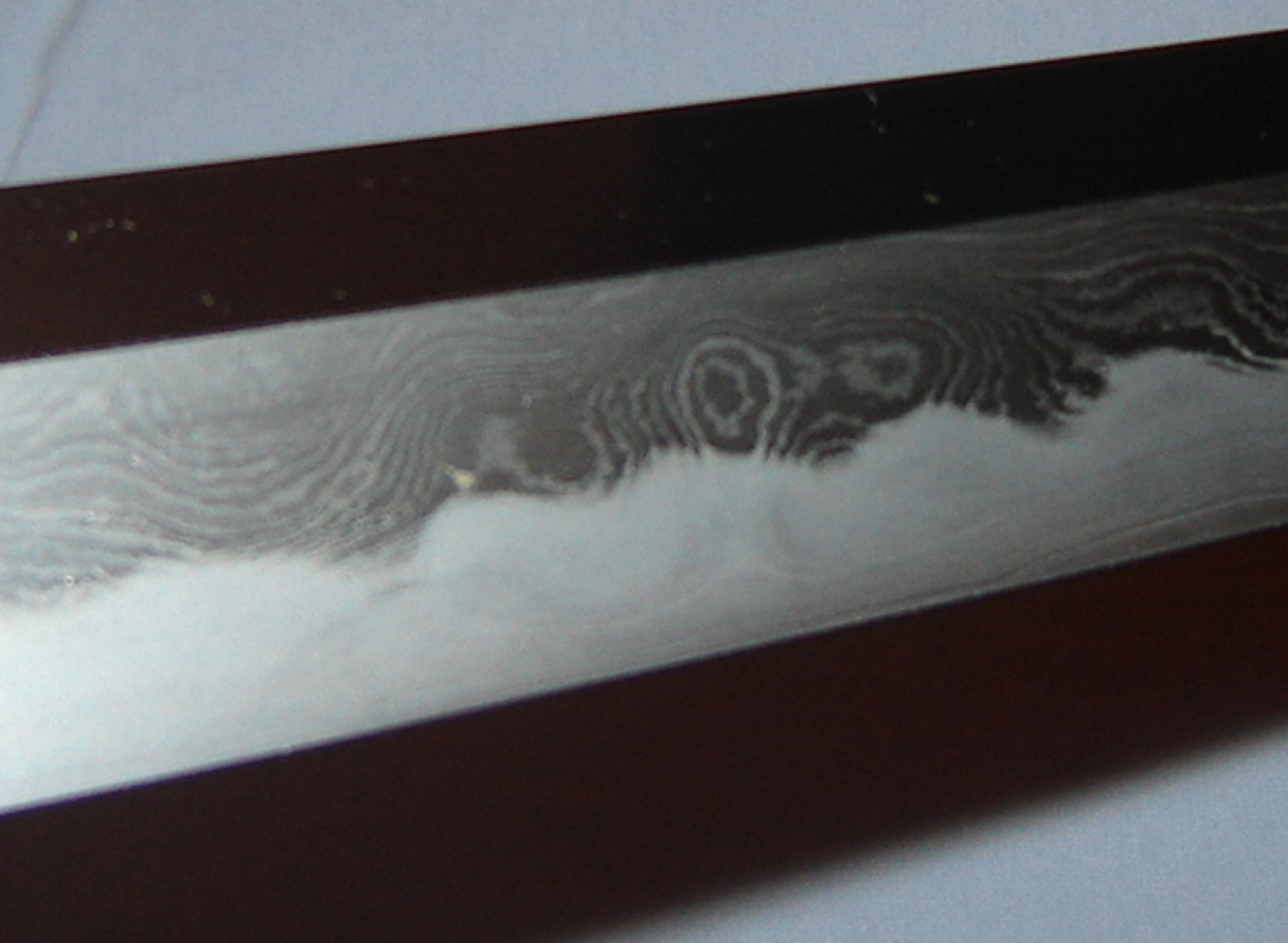

steel at the center and back of the sword. This difference in hardness is the objective of the process; the appearance is purely a side effect. However, the aesthetic qualities of the hamon are quite valuable—not only as proof of the differential-hardening treatment but also in its artistic value—and the patterns can be quite complex.

Types

The shape of the hamon is affected by many factors, but is primarily controlled by the shape of the clay coating at the time of quenching. Although each school had its own methods of application, and kept secret the process, the exact mixture of the clay, the thickness of the coat, and even the temperature of the water, the clay was usually applied by painting it on in very thin layers, to help prevent shrinking, peeling, and cracking as it dried. Often, the clay is applied to the entire blade by piling up the layers very thickly over the entire sword, and then the clay was carefully cut away from the edge. However, in ancient times tempering was rarely used in Asia, and a fully exposed edge would cool too fast and become far too brittle, thus a thinner layer of clay was usually applied to the edge so as to achieve the correct hardness upon quenching without the need for tempering afterwards.

The smith shapes the hamon at the time of coating the blade. There are two basic styles, which are "straight edge" (''sugaha'') and "irregular pattern" (''midare'' or ''midareba''). Straight-edge hamons simply follow the edge of the sword with little deviation, except at the tip. This was by far the most popular style in every era and in every province, whereas the more complex patterns that were in themselves works of art tended to be reserved for the wealthy and elite. Straight patterns are usually classified by the width of the hardened zone (''yakiba''), and divided into "wide" (''hiro''), "medium" (''cho''), "narrow" (''hoso''), and extremely narrow or "string" (''ito'') hamons.

Conversely, irregular hamons do not simply follow the edge, but deviate from it considerably in various ways. The two main groups are "undulating" or "wavy" (''notare'') and tooth-like or "zig-zag" (''gunome''), and these are often classified by the

The shape of the hamon is affected by many factors, but is primarily controlled by the shape of the clay coating at the time of quenching. Although each school had its own methods of application, and kept secret the process, the exact mixture of the clay, the thickness of the coat, and even the temperature of the water, the clay was usually applied by painting it on in very thin layers, to help prevent shrinking, peeling, and cracking as it dried. Often, the clay is applied to the entire blade by piling up the layers very thickly over the entire sword, and then the clay was carefully cut away from the edge. However, in ancient times tempering was rarely used in Asia, and a fully exposed edge would cool too fast and become far too brittle, thus a thinner layer of clay was usually applied to the edge so as to achieve the correct hardness upon quenching without the need for tempering afterwards.

The smith shapes the hamon at the time of coating the blade. There are two basic styles, which are "straight edge" (''sugaha'') and "irregular pattern" (''midare'' or ''midareba''). Straight-edge hamons simply follow the edge of the sword with little deviation, except at the tip. This was by far the most popular style in every era and in every province, whereas the more complex patterns that were in themselves works of art tended to be reserved for the wealthy and elite. Straight patterns are usually classified by the width of the hardened zone (''yakiba''), and divided into "wide" (''hiro''), "medium" (''cho''), "narrow" (''hoso''), and extremely narrow or "string" (''ito'') hamons.

Conversely, irregular hamons do not simply follow the edge, but deviate from it considerably in various ways. The two main groups are "undulating" or "wavy" (''notare'') and tooth-like or "zig-zag" (''gunome''), and these are often classified by the wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tro ...

or breadth of the irregularities. Sometimes hamons can consist of one style, a mixture of two, or all three (e.g.: ''gunome midare'', ''notare midare'', '' toran midare'', etc.), with many other differences sometimes added in for effect. ''Kataochi gunome'' resembled saw teeth, whereas ''uma-no-ha gunome'' resembled horse teeth. ''Fukushiki gunome'' consists of multiple sizes and shapes of teeth mixed with areas of regularly sized and shaped teeth. ''Koshi-no-hiraita midare'' consists of waves with wide valleys and steep crests, and were mainly found on ''Bizen'' swords of the Muromachi period

The is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate (''Muromachi bakufu'' or ''Ashikaga bakufu''), which was officially established in 1338 by t ...

.

The specific shape and style of the hamons were often unique and served as a sort of signature of the various swordsmithing schools or even for individual smiths that produced them. ''Kataochi gunome'' originated with Osafune Kagemitsu and was carried on by Kunimitsu, whereas ''togari gunome'' (very orderly and pointed peaks) were mainly found on swords of the Sue-Seki school. On the most ancient swords, the hamon typically ended just before the sword guard, but on most later and contemporary swords the hamon extends far past the guard, under the handle, and ends with the tang, which provided added strength to the tang.

The shape of the hamon is affected by other factors as well. If a sword is made of a composite steel (as most ancient swords were) consisting of alternating layers of steel with different carbon contents, then the steel with higher hardenability will change into martensite deeper underneath the clay coating than the lower-carbon steel. This leaves a pattern of bright streaks that jut a short distance away from the hamon, called ''niye'', which give it a wispy, misty, or foggy appearance. Likewise, complex swords that consist of sections of different steels welded together may show evidence of the welds near the hamon.

Modern reproductions

etching

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types ...

, sandblasting, or more crude ones such as wire brush

A wire brush is a tool consisting of a brush whose bristles are made of wire, most often steel wire. The steel used is generally a medium- to high-carbon variety and very hard and springy. Other wire brushes feature bristles made from brass ...

ing. Some modern reproductions with natural hamons are also subjected to acid etching to enhance their hamons' prominence. A true hamon can be easily discerned by the presence of a "nioi," which is a bright, speckled line a few millimeters wide, following the length of the hamon. The nioi is typically best viewed at long angles, and cannot be faked with etching or other methods. When viewed through a magnifying lens, the nioi appears as a sparkly line, being made up of many bright martensite grains, which are surrounded by darker, softer pearlite.

Origins

China was the first country to produce iron in Asia, around 1200 BC. The Chinese developedcast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

, and from this developed processes of making wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

, mild steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

, and crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other flux (metallurgy), fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using char ...

. For a period of over 1000 years, from the first to the eleventh century, China was the world's largest producer and exporter of steel and iron. Nearly all metals then were imported into Japan from China, through Korea, including swords and weapons. Iron-making technology was typically a closely guarded secret, but was eventually imported into Japan from China around 600 or 700 AD, albeit with only a small amount of information to build on, so the ancient smiths began by trying to reverse engineer

Reverse engineering (also known as backwards engineering or back engineering) is a process or method through which one attempts to understand through deductive reasoning how a previously made device, process, system, or piece of software accompli ...

the Chinese methods, coming up with very different processes in the end.

The Chinese swords had edges made of crucible steel similar to the metal found in Damascus swords, which were welded to a back of soft iron, to give both a hard and strong cutting edge but keeping the rest of the sword soft to prevent breakage. These produced a very hard and visible patterned-edge with a very visible transition at the weld, due to the different composition of the steels, despite the lack of any form of heat treatment. In tying to imitate the Chinese swords, the Japanese came up with unique processes and their own methods of creating a visible hardened edge, taking the Chinese methods and "refining them beyond recognition".

According to legend, Amakuni Yasutsuna

is the legendary swordsmith who supposedly created the first single-edged longsword (tachi) with curvature along the edge in the Yamato Province around 700 AD. He was the head of a group of swordsmiths employed by the Emperor of Japan to make we ...

developed the process of differentially hardening the blades around the 8th century AD. The emperor was returning from battle with his soldiers when Amakuni noticed that half of the swords were broken:

Although impossible to ascertain who actually invented the technique, surviving blades by Amakuni from around 749–811 AD suggest that at the very least Amakuni helped establish the tradition of differentially hardening the blades.

In the most ancient swords, all hamons were of the straight-edge variety. Irregular patterns started to emerge around the 1300s, with famous smiths such as Kunimitsu, Muramasa, and Masamune

, was a medieval Japanese blacksmith widely acclaimed as Japan's greatest swordsmith. He created swords and daggers, known in Japanese as ''tachi'' and ''tantō'', in the ''Sōshū'' school. However, many of his forged ''tachi'' were made into ...

, among many others. By the 1600--1700s, hamons with various shapes in them became common, such as trees, flowers, rat's feet, clovers, pillboxes, and many others. Common themes included ''juka choji'' (multiple, overlapping clovers), ''kikusui'' (chrysanthemum

Chrysanthemums (), sometimes called mums or chrysanths, are flowering plants of the genus ''Chrysanthemum'' in the family Asteraceae. They are native to East Asia and northeastern Europe. Most species originate from East Asia and the center ...

s floating on a stream), ''Yoshino'' (cherry blossom

A cherry blossom, also known as Japanese cherry or sakura, is a flower of many trees of genus ''Prunus'' or ''Prunus'' subg. ''Cerasus''. They are common species in East Asia, including China, Korea and especially in Japan. They generally ...

s on the Yoshino River

The Yoshino River (吉野川 ''Yoshino-gawa'') is a river on the island of Shikoku, Japan. It is long and has a watershed of . It is the second longest river in Shikoku (slightly shorter than the Shimanto), and is the only river whose watershe ...

), or ''Tatsuta'' (maple leaves

The maple leaf is the characteristic leaf of the maple tree. It is the most widely recognized national symbol of Canada.

History of use in Canada

By the early 1700s, the maple leaf had been adopted as an emblem by the French Canadians along the ...

on the Tatsuta River Tatsuta may refer to:

* Tatsuta, Aichi, a former village in Japan, merged into the city of Aisai in 2010

* , a pre-war Japanese ocean liner of the NYK Line

* , an unprotected cruiser in the early Imperial Japanese Navy

* , the second vessel of the ...

). By the 1800s, with the addition of decorative forging techniques, hamons were being created that depicted entire landscapes. These often depicted specific scenery or skyline

A skyline is the outline or shape viewed near the horizon. It can be created by a city’s overall structure, or by human intervention in a rural setting, or in nature that is formed where the sky meets buildings or the land.

City skylines ...

s familiar in everyday life, such as specific islands or mountains, towns and cities, grassy country-sides, or violent crashing-waves in the ocean complete with sandy beaches and spraying surf. A common such design was ''Fujimi Saigyo'' (Priest Saigyo viewing Mount Fuji

, or Fugaku, located on the island of Honshū, is the highest mountain in Japan, with a summit elevation of . It is the second-highest volcano located on an island in Asia (after Mount Kerinci on the island of Sumatra), and seventh-highest p ...

). Sometimes low spots were cut into the clay to produce ''niye'' disconnected from the hamon in the center of the blade, creating the appearance of stars, clouds, wind-blown snowy peaks, or even birds in the sky.''The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords'' by Kokan Nagayama -- Kodansha International 1997 Page 92--96

See also

* Glossary of Japanese swords *Pattern welding

Pattern welding is the practice in sword and knife making of forming a blade of several metal pieces of differing composition that are forge welding, forge-welded together and twisted and manipulated to form a pattern. Often mistakenly called Dam ...

References

{{ReflistExternal links

Cheness Inc page about Hamons and how to differentiate fakes

Japanese swords