Hafez Abu Seada 5-3-2019 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Khwāje Shams-od-Dīn Moḥammad Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī ( fa, خواجه شمسالدین محمّد حافظ شیرازی), known by his

Hafez was born in Shiraz, Iran. Few details of his life are known. Accounts of his early life rely upon traditional anecdotes. Early '' tazkiras'' (biographical sketches) mentioning Hafez are generally considered unreliable. At an early age, he memorized the Quran and was given the title of '' Hafez'', which he later used as his pen name. The preface of his Divān, in which his early life is discussed, was written by an unknown contemporary whose name may have been Moḥammad Golandām.Khorramshahi. Accessed 25 July 2010 Two of the most highly regarded modern editions of Hafez's Divān are compiled by Moḥammad Ghazvini and Qāsem Ḡani (495 ''ghazals'') and by Parviz Natel-Khanlari (486 ''ghazals'').Lewisohn, p. 69. Hafez was a

Hafez was born in Shiraz, Iran. Few details of his life are known. Accounts of his early life rely upon traditional anecdotes. Early '' tazkiras'' (biographical sketches) mentioning Hafez are generally considered unreliable. At an early age, he memorized the Quran and was given the title of '' Hafez'', which he later used as his pen name. The preface of his Divān, in which his early life is discussed, was written by an unknown contemporary whose name may have been Moḥammad Golandām.Khorramshahi. Accessed 25 July 2010 Two of the most highly regarded modern editions of Hafez's Divān are compiled by Moḥammad Ghazvini and Qāsem Ḡani (495 ''ghazals'') and by Parviz Natel-Khanlari (486 ''ghazals'').Lewisohn, p. 69. Hafez was a

'agar 'ān Tork-e Šīrāzī * be dast ārad del-ē mā-rā

be khāl-ē Hendu-yaš baxšam * Samarqand ō Boxārā-rā

If that Shirazi Turk accepts my heart in their hand,

for their Indian mole I will give Samarkand and Bukhara.

His tomb is "crowded with devotees" who visit the site and the atmosphere is "festive" with visitors singing and reciting their favorite Hafez poems.

Many Iranians use Divan of Hafez for fortune telling. Iranian families usually have a Divan of Hafez in their house, and when they get together during the Nowruz or Yaldā holidays, they open the Divan to a random page and read the poem on it, which they believe to be an indication of things that will happen in the future.

His tomb is "crowded with devotees" who visit the site and the atmosphere is "festive" with visitors singing and reciting their favorite Hafez poems.

Many Iranians use Divan of Hafez for fortune telling. Iranian families usually have a Divan of Hafez in their house, and when they get together during the Nowruz or Yaldā holidays, they open the Divan to a random page and read the poem on it, which they believe to be an indication of things that will happen in the future.

Though Hafez is well known for his poetry, he is less commonly recognized for his intellectual and political contributions. A defining feature of Hafez' poetry is its ironic tone and the theme of hypocrisy, widely believed to be a critique of the religious and ruling establishments of the time. Persian satire developed during the 14th century, within the courts of the

Though Hafez is well known for his poetry, he is less commonly recognized for his intellectual and political contributions. A defining feature of Hafez' poetry is its ironic tone and the theme of hypocrisy, widely believed to be a critique of the religious and ruling establishments of the time. Persian satire developed during the 14th century, within the courts of the

The Collected Lyrics of Hafiz of Shiraz

', 603 p. (Cambridge: Archetype, 2007).

Translated from ''Divān-e Hāfez'', Vol. 1, ''The Lyrics (Ghazals)'', edited by Parviz Natel-Khanlari ( Tehran, Iran, 1362 AH/1983-4). * Loloi, Parvin, ''Hafiz, Master of Persian Poetry: A Critical Bibliography - English Translations Since the Eighteenth Century'' (2004. I.B. Tauris) * Browne, E. G., ''Literary History of Persia''. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and twenty-five years in the writing with a new introduction by J.T.P De Bruijn). 1997. * Will Durant, ''The Reformation''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957 * Erkinov, A., “Manuscripts of the works by classical Persian authors (Hāfiz, Jāmī, Bīdil): Quantitative Analysis of 17th-19th c. Central Asian Copies”. ''Iran: Questions et connaissances. Actes du IVe Congrès Européen des études iraniennes organisé par la Societas Iranologica Europaea'', Paris, 6-10 Septembre 1999. vol. II: Périodes médiévale et moderne. ahiers de Studia Iranica. 26 M.Szuppe (ed.). Association pour l`avancement des études iraniennes-Peeters Press. Paris-Leiden, 2002, pp. 213–228. * Hafez, ''The Poems of Hafez''. Trans. Reza Ordoubadian. Ibex Publishers, 2006 * Hafez, ''The Green Sea of Heaven: Fifty ghazals from the Diwan of Hafiz''. Trans. Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. White Cloud Press, 1995 * Hafez, ''The Angels Knocking on the Tavern Door: Thirty Poems of Hafez.'' Trans. Robert Bly and Leonard Lewisohn. HarperCollins, 2008, p. 69. * Hafez, ''Divan-i-Hafiz'', translated by Henry Wilberforce-Clarke, Ibex Publishers, Inc., 2007. * * * Jan Rypka, ''History of Iranian Literature''. Reidel Publishing Company. 1968 . * Chopra, R. M., "Great Poets of Classical Persian", June 2014, Sparrow Publication, Kolkata, . * * * *

Hafiz Selections of his poetry on Allspirit

Hafez in English from ''Poems Found in Translation'' website

Life and Poetry of Hafez from "Hafiz on Love" website

Persian texts and resources

''Hafez Divan'' with readings in Persian

Scan of 1560 ''Dīwān Hāfiz'' manuscript on archive.org

An online Flash application of his poems in Persian.

Text-Based Fal e Hafez

A light-weight website ranked 1 on search engines for Fal e Hafez.

Fale Hafez iPhone App

an iPhone application for reading poems and taking 'faal'.

''Radio Programs on Hafez's life and poetry'

English language resources * *

, a translation of the Divan-i Hafiz by Peter Avery, published b

Archetype

2007 hb; pb

by Iraj Bashiri, University of Minnesota.

''Hafiz, Shams al-Din Muhammad''

A Biography by Iraj Bashiri

1979, by Iraj Bashiri

on the '' Encyclopædia Iranica'' ( Columbia University).

HAFEZ – Encyclopaedia Iranica

* * Other

Hafez Tomb in 2012 Nowruz Celebration

Photos. * {{Authority control 14th-century Persian-language poets Sufi poets Mystic poets People from Shiraz 1320s births 1390 deaths Angelic visionaries Injuid-period poets 14th-century Iranian people

pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

Hafez (, ''Ḥāfeẓ'', 'the memorizer; the (safe) keeper'; 1325–1390) and as "Hafiz", was a Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

lyric poet

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

, whose collected works are regarded by many Iranians as a pinnacle of Persian literature

Persian literature ( fa, ادبیات فارسی, Adabiyâte fârsi, ) comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources h ...

. His works are often found in the homes of people in the Persian-speaking world, who learn his poems by heart and use them as everyday proverbs and sayings. His life and poems have become the subjects of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, influencing post-14th century Persian writing more than any other Persian author.

Hafez is best known for his Divan of Hafez, a collection of his surviving poems probably compiled after his death. His works can be described as "antinomian

Antinomianism (Ancient Greek: ἀντί 'anti''"against" and νόμος 'nomos''"law") is any view which rejects laws or Legalism (theology), legalism and argues against moral, religious or social norms (Latin: mores), or is at least consid ...

" and with the medieval use of the term "theosophical"; the term " theosophy" in the 13th and 14th centuries was used to indicate mystical work by "authors only inspired by the holy books

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

" (as distinguished from theology). Hafez primarily wrote in the literary genre of lyric poetry or ghazals, that is the ideal style for expressing the ecstasy of divine inspiration in the mystical form of love poems. He was a Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

.

Themes of his ghazals include the beloved, faith and exposing hypocrisy. In his ghazals he deals with love, wine and taverns, all presenting ecstasy

Ecstasy may refer to:

* Ecstasy (emotion), a trance or trance-like state in which a person transcends normal consciousness

* Religious ecstasy, a state of consciousness, visions or absolute euphoria

* Ecstasy (philosophy), to be or stand outside o ...

and freedom from restraint, whether in actual worldly release or in the voice of the lover speaking of divine love.Shaida, Khalid Hameed (2014). Hafiz, Drunk with God: Selected Odes. Xlibris Corporation. p. 5. . Retrieved 2016-08-23. His influence on Persian speakers appears in divination by his poems ( fa, links=no, فال حافظ, ''fāl-e hāfez'', somewhat similar to the Roman tradition of ''sortes vergilianae

The Sortes Vergilianae (''Virgilian Lots'') is a form of divination by bibliomancy in which advice or predictions of the future are sought by interpreting passages from the works of the Roman poet Virgil. The use of Virgil for divination may dat ...

'') and in the frequent use of his poems in Persian traditional music

Persian traditional music or Iranian traditional music, also known as Persian classical music or Iranian classical music, refers to the classical music of Iran (also known as ''Persia''). It consists of characteristics developed through the coun ...

, visual art and Persian calligraphy. His tomb is located in his birthplace of Shiraz. Adaptations, imitations and translations of his poems exist in all major languages.

Life

Hafez was born in Shiraz, Iran. Few details of his life are known. Accounts of his early life rely upon traditional anecdotes. Early '' tazkiras'' (biographical sketches) mentioning Hafez are generally considered unreliable. At an early age, he memorized the Quran and was given the title of '' Hafez'', which he later used as his pen name. The preface of his Divān, in which his early life is discussed, was written by an unknown contemporary whose name may have been Moḥammad Golandām.Khorramshahi. Accessed 25 July 2010 Two of the most highly regarded modern editions of Hafez's Divān are compiled by Moḥammad Ghazvini and Qāsem Ḡani (495 ''ghazals'') and by Parviz Natel-Khanlari (486 ''ghazals'').Lewisohn, p. 69. Hafez was a

Hafez was born in Shiraz, Iran. Few details of his life are known. Accounts of his early life rely upon traditional anecdotes. Early '' tazkiras'' (biographical sketches) mentioning Hafez are generally considered unreliable. At an early age, he memorized the Quran and was given the title of '' Hafez'', which he later used as his pen name. The preface of his Divān, in which his early life is discussed, was written by an unknown contemporary whose name may have been Moḥammad Golandām.Khorramshahi. Accessed 25 July 2010 Two of the most highly regarded modern editions of Hafez's Divān are compiled by Moḥammad Ghazvini and Qāsem Ḡani (495 ''ghazals'') and by Parviz Natel-Khanlari (486 ''ghazals'').Lewisohn, p. 69. Hafez was a Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

.

Modern scholars generally agree that he was born either in 1315 or 1317. According to an account by Jami, Hafez died in 1390. Hafez was supported by patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

from several successive local regimes: Shah Abu Ishaq, who came to power while Hafez was in his teens; Timur at the end of his life; and even the strict ruler Shah Mubariz ud-Din Muhammad ( Mubariz Muzaffar). Though his work flourished most under the 27-year rule of Jalal ud-Din Shah Shuja (Shah Shuja Shāh Shujā' ( fa, شاه شجاع, meaning: ''brave king'') may refer to the following:

*Shah Shoja Mozaffari, the 14th-century Muzaffarid ruler of Southern Iran

*Shah Shuja (Mughal prince) (1616-1661), the second son of Shah Jahan

*Shah Shujah D ...

),Gray, pp. 2-4. it is claimed Hāfez briefly fell out of favor with Shah Shuja for mocking inferior poets (Shah Shuja wrote poetry himself and may have taken the comments personally), forcing Hāfez to flee from Shiraz to Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

and Yazd, but no historical evidence is available. Hafez also exchanged letters and poetry with Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah, the Sultan of Bengal, who invited him to Sonargaon though he could not make it.

Twenty years after his death, a tomb, the ''Hafezieh'', was erected to honor Hafez in the Musalla Gardens in Shiraz. The current mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

was designed by André Godard, a French archeologist and architect, in the late 1930s, and the tomb is raised up on a dais amidst rose gardens, water channels, and orange trees. Inside, Hafez's alabaster sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek ...

bears the inscription of two of his poems.

Legends

Many semi-miraculous mythical tales were woven around Hafez after his death. It is said that by listening to his father's recitations, Hafez had accomplished the task of learning the Quran by heart at an early age (that is the meaning of the word ''Hafez''). At the same time, he is said to have known by heart the works ofRumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

( Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi), Saadi, Farid ud-Din, and Nizami.

According to one tradition, before meeting his self-chosen Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

master Hajji Zayn al-Attar, Hafez had been working in a bakery, delivering bread to a wealthy quarter of the town. There, he first saw Shakh-e Nabat, a woman of great beauty, to whom some of his poems are addressed. Ravished by her beauty but knowing that his love for her would not be requited, he allegedly held his first mystic vigil in his desire to realize this union. Still, he encountered a being of surpassing beauty who identified himself as an angel, and his further attempts at union became mystic; a pursuit of spiritual union with the divine.

At 60, he is said to have begun a ''Chilla-nashini

Chilla ( fa, چله, ar, أربعين, both literally "forty"), also known as Chilla-nashini, is a spiritual practice of penance and solitude in Sufism known mostly in Indian and Persian traditions. In this ritual a mendicant or ascetic

As ...

'', a 40-day-and-night vigil by sitting in a circle that he had drawn for himself. On the 40th day, he once again met with Zayn al-Attar on what is known to be their fortieth anniversary and was offered a cup of wine. It was there where he is said to have attained "Cosmic Consciousness". He hints at this episode in one of his verses in which he advises the reader to attain "clarity of wine" by letting it "sit for 40 days".

In one tale, Tamerlane (Timur) angrily summoned Hafez to account for one of his verses:

Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, ...

was Tamerlane's capital and Bokhara was the kingdom's finest city. "With the blows of my lustrous sword", Timur complained, "I have subjugated most of the habitable globe... to embellish Samarkand and Bokhara, the seats of my government; and you would sell them for the black mole of some girl in Shiraz!"

Hafez, the tale goes, bowed deeply and replied, "Alas, O Prince, it is this prodigality which is the cause of the misery in which you find me". So surprised and pleased was Timur with this response that he dismissed Hafez with handsome gifts.

Influence

Intellectual and artistic legacy

Hafez was acclaimed throughout theIslamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

during his lifetime, with other Persian poets

The list is not comprehensive, but is continuously being expanded and includes Persian poets as well as poets who write in Persian from Iran, Azerbaijan, Iraq, Georgia, Dagestan, Turkey, Syria, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Le ...

imitating his work, and offers of patronage from Baghdad to India.

His work was first translated into English in 1771 by William Jones. It would leave a mark on such Western writers as Thoreau, Goethe, W. B. Yeats, in his prose anthology book of essays, ''Discoveries'', as well as gaining a positive reception within West Bengal, in India, among some of the most prolific religious leaders and poets in this province, Debendranath Tagore, Rabindranath Tagore's father, who knew Persian and used to recite from Hafez's Divans and in this line, Gurudev himself, who, during his visit to Persia in 1932, also made a homage visit to Hafez's tomb in Shiraz and Ralph Waldo Emerson (the last referred to him as "a poet's poet"). Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

has his character Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

state that "there is as much sense in Hafiz as in Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, and as much knowledge of the world" (in A Case of Identity). Friedrich Engels mentioned him in an 1853 letter to Karl Marx.

There is no definitive version of his collected works (or ''Dīvān''); editions vary from 573 to 994 poems. Only since the 1940s has a sustained scholarly attempt (by Mas'ud Farzad

Masoud (; ) is a given name and surname, with origins in Persian and Arabic. The name is found in the Arab world, Iran, Turkey, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Russia, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and China. Masoud has spelling varia ...

, Qasim Ghani Qasim, Qasem or Casim may refer to:

* Qasim (name), a given name of Arabic origin and the name of several people

* Port Qasim, port in Karachi, Pakistan

* ''Kasım'' and ''Casim'', respectively the Ottoman Turkish and Romanian names for General To ...

and others in Iran) been made to authenticate his work and to remove errors introduced by later copyist

A copyist is a person that makes duplications of the same thing. The term is sometimes used for artists who make copies of other artists' paintings. However, the modern use of the term is almost entirely confined to music copyists, who are emplo ...

s and censors. However, the reliability of such work has been questioned, and in the words of Hāfez scholar Iraj Bashiri, "there remains little hope from there (i.e.: Iran) for an authenticated diwan".

In contemporary Iranian culture

Hafez is the most popular poet in Iran, and his works can be found in almost every Iranian home. In fact, October 12 is celebrated as Hafez Day in Iran. His tomb is "crowded with devotees" who visit the site and the atmosphere is "festive" with visitors singing and reciting their favorite Hafez poems.

Many Iranians use Divan of Hafez for fortune telling. Iranian families usually have a Divan of Hafez in their house, and when they get together during the Nowruz or Yaldā holidays, they open the Divan to a random page and read the poem on it, which they believe to be an indication of things that will happen in the future.

His tomb is "crowded with devotees" who visit the site and the atmosphere is "festive" with visitors singing and reciting their favorite Hafez poems.

Many Iranians use Divan of Hafez for fortune telling. Iranian families usually have a Divan of Hafez in their house, and when they get together during the Nowruz or Yaldā holidays, they open the Divan to a random page and read the poem on it, which they believe to be an indication of things that will happen in the future.

In Iranian music

In the genre of Persian classical music Hafez along with Sa'di have been the most popular poets in the art of āvāz, non-metered form of singing. Also the form 'Sāqi-Nāmeh' in the radif of Persian music is based on the same title by Hafez. A number of contemporary composers such as Parviz Meshkatian (Sheydaie), Hossein Alizadeh (Ahu-ye Vahshi), Mohammad Reza Lotfi (Golestān), and Siamak Aghaie (Yād Bād) have composed metric songs (tasnif) based on ghazals of Hafez which have become very popular in the genre of classical music. Hayedeh performed the song "Padeshah-e Khooban", with music by Farid Zoland. The Ottoman composerBuhurizade Mustafa Itri

Mustafa Itri, more commonly known as Buhurizade Mustafa Itri, or just simply Itri (1640 - 1712) was an Ottoman-Turkish musician, composer, singer and poet. With over a thousand works to his name, although only about forty of these have survived t ...

composed his magnum opus Neva Kâr based upon one of Hafez's poems. The Polish composer Karol Szymanowski

Karol Maciej Szymanowski (; 6 October 188229 March 1937) was a Polish composer and pianist. He was a member of the modernist Young Poland movement that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Szymanowski's early works show the inf ...

composed The Love Songs of Hafiz based upon a German translation of Hafez poems.

In Afghan music

Many Afghan singers, including Ahmad Zahir and Sarban, have composed songs such as "Ay Padeshah-e Khooban", "Gar-Zulfe Parayshanat".Interpretation

The question of whether his work is to be interpreted literally, mystically, or both has been a source of contention among western scholars. On the one hand, some of his early readers such as William Jones saw in him a conventional lyricist similar to European love poets such as Petrarch. Others scholars such asHenry Wilberforce Clarke

Henry Wilberforce Clarke (1840–1905) was the British translator of Persian works by mystic poets Saadi, Hafez, Nizami and Suhrawardi, as well as writing some works himself. He was an officer in the British India corps Bengal Engineers, and ...

saw him as purely a poet of didactic, ecstatic mysticism in the manner of Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

, a view that a minority of twentieth century critics and literary historians have come to challenge. Ralph Waldo Emerson rejected the Sufistic view of wine in Hafez's poems.

This confusion stems from the fact that, early in Persian literary history, the poetic vocabulary was usurped by mystics, who believed that the ineffable could be better approached in poetry than in prose. In composing poems of mystic content, they imbued every word and image with mystical undertones, causing mysticism and lyricism to converge into a single tradition. As a result, no fourteenth-century Persian poet could write a lyrical poem without having a flavor of mysticism forced on it by the poetic vocabulary itself. While some poets, such as Ubayd Zakani, attempted to distance themselves from this fused mystical-lyrical tradition by writing satires, Hafez embraced the fusion and thrived on it. Wheeler Thackston has said of this that Hafez "sang a rare blend of human and mystic love so balanced... that it is impossible to separate one from the other".

For reasons such as that, the history of the translation of Hāfez is fraught with complications, and few translations into western languages have been wholly successful.

One of the figurative gestures for which he is most famous (and which is among the most difficult to translate) is ''īhām

''Īhām'' (ایهام) in Persian, Urdu, Kurdish and Arabic poetry is a literary device in which an author uses a word, or an arrangement of words, that can be read in several ways. Each of the meanings may be logically sound, equally true and i ...

'' or artful punning. Thus, a word such as ''gowhar'', which could mean both "essence, truth" and "pearl", would take on ''both'' meanings at once as in a phrase such as "a pearl/essential truth outside the shell of superficial existence".

Hafez often took advantage of the aforementioned lack of distinction between lyrical, mystical, and panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

writing by using highly intellectualized, elaborate metaphors and images to suggest multiple possible meanings. For example, a couplet

A couplet is a pair of successive lines of metre in poetry. A couplet usually consists of two successive lines that rhyme and have the same metre. A couplet may be formal (closed) or run-on (open). In a formal (or closed) couplet, each of the ...

from one of Hafez's poems reads:

The cypress

Cypress is a common name for various coniferous trees or shrubs of northern temperate regions that belong to the family Cupressaceae. The word ''cypress'' is derived from Old French ''cipres'', which was imported from Latin ''cypressus'', the ...

tree is a symbol both of the beloved and of a regal presence; the nightingale and birdsong evoke the traditional setting for human love. The "lessons of spiritual stations" suggest, obviously, a mystical undertone as well (though the word for "spiritual" could also be translated as "intrinsically meaningful"). Therefore, the words could signify at once a prince addressing his devoted followers, a lover courting a beloved, and the reception of spiritual wisdom.Meisami, Julie Scott. "Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez." '' International Journal of Middle East Studies'' 17(2) (May 1985), 229-260

Satire, religion, and politics

Though Hafez is well known for his poetry, he is less commonly recognized for his intellectual and political contributions. A defining feature of Hafez' poetry is its ironic tone and the theme of hypocrisy, widely believed to be a critique of the religious and ruling establishments of the time. Persian satire developed during the 14th century, within the courts of the

Though Hafez is well known for his poetry, he is less commonly recognized for his intellectual and political contributions. A defining feature of Hafez' poetry is its ironic tone and the theme of hypocrisy, widely believed to be a critique of the religious and ruling establishments of the time. Persian satire developed during the 14th century, within the courts of the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

. In this period, Hafez and other notable early satirists, such as Ubayd Zakani, produced a body of work that has since become a template for the use of satire as a political device. Many of his critiques are believed to be targeted at the rule of Mubariz al-Din Muhammad, specifically, towards the disintegration of important public and private institutions.

His work, particularly his imaginative references to monasteries, convents, Shahneh, and muhtasib, ignored the religious taboos of his period, and he found humor in some of his society's religious doctrines. Employing humor polemically has since become a common practice in Iranian public discourse and satire is now perhaps the de facto language of Iranian social commentary.

Modern English editions

A standard modern English edition of Hafez is ''Faces of Love'' (2012) translated by Dick Davis for Penguin Classics. ''Beloved: 81 poems from Hafez'' (Bloodaxe Books

Bloodaxe Books is a British publishing house specializing in poetry.

History

Bloodaxe Books was founded in 1978 in Newcastle upon Tyne by Neil Astley, who is still editor and managing director. Bloodaxe moved its editorial office to Northumbe ...

, 2018) is a recent English selection noted by Fatemeh Keshavarz

Fatemeh Keshavarz Ph.D. ( fa, فاطمه كشاورز) is an Iranian academic, Rumi and Persian studies scholar, and a poet in Persian and English. She is the Roshan Chair of Persian Studies and Director of the Roshan Institute for Persian Studies ...

(Roshan Institute for Persian studies, University of Maryland) for preserving "that audacious and multilayered richness one finds in the originals".

Peter Avery translated a complete edition of Hafez in English, ''The Collected Lyrics of Hafiz of Shiraz'', published in 2007. hb; pb It was awarded Iran's Farabi prize."Obituary: Peter Avery", ''The Daily Telegraph'', (14 October 2008), page 29, (not online 19 October 2008) Avery's translations are published with notes explaining allusions in the text and filling in what the poets would have expected their readers to know. An abridged version exists, titled ''Hafiz of Shiraz: Thirty Poems: An Introduction to the Sufi Master''.

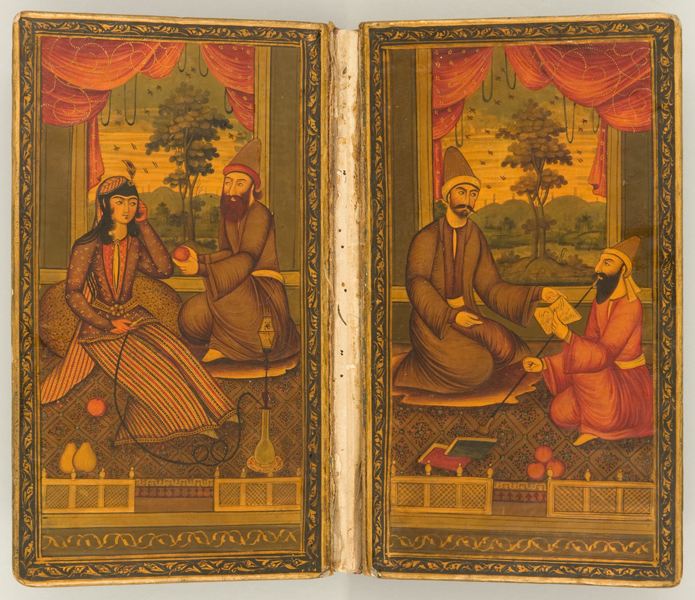

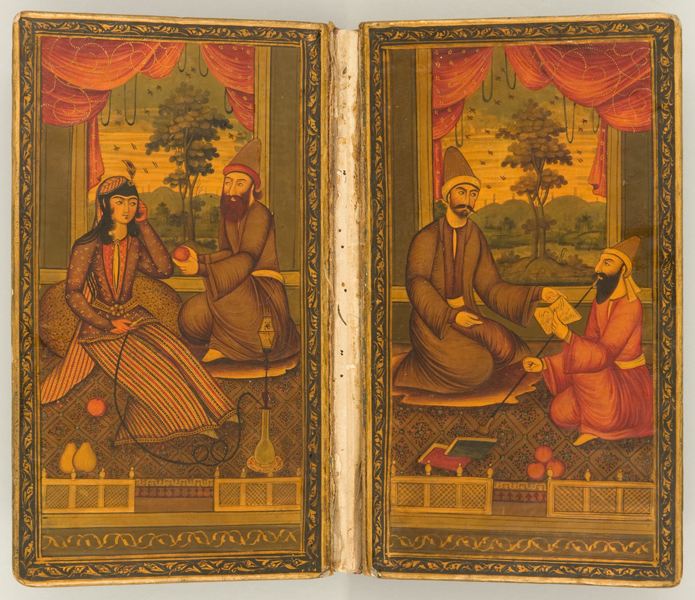

Divan-e-Hafez

Divan Hafez is a book containing all the remaining poems of Hafez. Most of these poems are in Persian and the most crucial part of this Divan isghazal

The ''ghazal'' ( ar, غَزَل, bn, গজল, Hindi-Urdu: /, fa, غزل, az, qəzəl, tr, gazel, tm, gazal, uz, gʻazal, gu, ગઝલ) is a form of amatory poem or ode, originating in Arabic poetry. A ghazal may be understood as a ...

s. There are poems in other poetic formats such as piece, ode, Masnavi

The ''Masnavi'', or ''Masnavi-ye-Ma'navi'' ( fa, مثنوی معنوی), also written ''Mathnawi'', or ''Mathnavi'', is an extensive poem written in Persian by Jalal al-Din Muhammad Balkhi, also known as Rumi. The ''Masnavi'' is one of the most ...

and quatrain

A quatrain is a type of stanza, or a complete poem, consisting of four lines.

Existing in a variety of forms, the quatrain appears in poems from the poetic traditions of various ancient civilizations including Persia, Ancient India, Ancient Greec ...

in this Divan.

There is no evidence that most of Hafez's poems were destroyed. In addition, Hafez was very famous during his lifetime; Therefore, the small number of poetry in the court indicates that he was not a prolific poet.

Hafez's Divan was probably compiled for the first time by Mohammad Glendam after his death. Of course, some unconfirmed reports indicate that Hafez published his court in 770 AH. that is, edited more than twenty years before his death.

Death and the tomb

The year of Hafez's death is 791 AH. Hafez was buried in the prayer hall of Shiraz calledhafezieh

The Tomb of Hafez ( Persian: آرامگاه حافظ), commonly known as Hāfezieh (), are two memorial structures erected in the northern edge of Shiraz, Iran, in memory of the celebrated Persian poet Hafez. The open pavilion structures are ...

. In 855 AH, after the conquest of Shiraz by Abolghasem Babar Teymouri, they built a tomb under the command of his minister, Maulana Mohammad Mamaei.

Poems by Hafez

The number in the edition by Muhammad Qazvini and Qasem Ghani (1941) is given, as well as that of Parviz Nātel-Khānlari (2nd ed. 1983): *'' Alā yā ayyoha-s-sāqī'' – QG 1; PNK 1 *'' Dūš dīdam ke malā'ek'' – QG 184; PNK 179 *'' Goftā borūn šodī'' – QG 406; PNK 398 *'' Mazra'-ē sabz-e falak'' – QG 407; PNK 399 *'' Naqdhā rā bovad āyā'' – QG 185; PNK 180 *'' Sālhā del talab-ē jām'' – QG 142 (Ganjoor 143); PNK 136 *'' Shirazi Turk'' – QG 3; PNK 3 *'' Sīne mālāmāl'' – QG 470; PNK 461 *'' Zolf-'āšofte'' – QG 26; PNK 22See also

* Diwan (poetry) * List of Persian poets and authors * Persian metres * Persian mysticism **Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

, Persian poet

*Persian literature

Persian literature ( fa, ادبیات فارسی, Adabiyâte fârsi, ) comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources h ...

*'' The Love Songs of Hafiz''

*'' West-östlicher Diwan''

References

Sources

* * Peter Avery,The Collected Lyrics of Hafiz of Shiraz

', 603 p. (Cambridge: Archetype, 2007).

Translated from ''Divān-e Hāfez'', Vol. 1, ''The Lyrics (Ghazals)'', edited by Parviz Natel-Khanlari ( Tehran, Iran, 1362 AH/1983-4). * Loloi, Parvin, ''Hafiz, Master of Persian Poetry: A Critical Bibliography - English Translations Since the Eighteenth Century'' (2004. I.B. Tauris) * Browne, E. G., ''Literary History of Persia''. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and twenty-five years in the writing with a new introduction by J.T.P De Bruijn). 1997. * Will Durant, ''The Reformation''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957 * Erkinov, A., “Manuscripts of the works by classical Persian authors (Hāfiz, Jāmī, Bīdil): Quantitative Analysis of 17th-19th c. Central Asian Copies”. ''Iran: Questions et connaissances. Actes du IVe Congrès Européen des études iraniennes organisé par la Societas Iranologica Europaea'', Paris, 6-10 Septembre 1999. vol. II: Périodes médiévale et moderne. ahiers de Studia Iranica. 26 M.Szuppe (ed.). Association pour l`avancement des études iraniennes-Peeters Press. Paris-Leiden, 2002, pp. 213–228. * Hafez, ''The Poems of Hafez''. Trans. Reza Ordoubadian. Ibex Publishers, 2006 * Hafez, ''The Green Sea of Heaven: Fifty ghazals from the Diwan of Hafiz''. Trans. Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. White Cloud Press, 1995 * Hafez, ''The Angels Knocking on the Tavern Door: Thirty Poems of Hafez.'' Trans. Robert Bly and Leonard Lewisohn. HarperCollins, 2008, p. 69. * Hafez, ''Divan-i-Hafiz'', translated by Henry Wilberforce-Clarke, Ibex Publishers, Inc., 2007. * * * Jan Rypka, ''History of Iranian Literature''. Reidel Publishing Company. 1968 . * Chopra, R. M., "Great Poets of Classical Persian", June 2014, Sparrow Publication, Kolkata, . * * * *

External links

English translations of Poetry by HafezHafiz Selections of his poetry on Allspirit

Hafez in English from ''Poems Found in Translation'' website

Life and Poetry of Hafez from "Hafiz on Love" website

Persian texts and resources

''Hafez Divan'' with readings in Persian

Scan of 1560 ''Dīwān Hāfiz'' manuscript on archive.org

An online Flash application of his poems in Persian.

Text-Based Fal e Hafez

A light-weight website ranked 1 on search engines for Fal e Hafez.

Fale Hafez iPhone App

an iPhone application for reading poems and taking 'faal'.

''Radio Programs on Hafez's life and poetry'

English language resources * *

, a translation of the Divan-i Hafiz by Peter Avery, published b

Archetype

2007 hb; pb

by Iraj Bashiri, University of Minnesota.

''Hafiz, Shams al-Din Muhammad''

A Biography by Iraj Bashiri

1979, by Iraj Bashiri

on the '' Encyclopædia Iranica'' ( Columbia University).

HAFEZ – Encyclopaedia Iranica

* * Other

Hafez Tomb in 2012 Nowruz Celebration

Photos. * {{Authority control 14th-century Persian-language poets Sufi poets Mystic poets People from Shiraz 1320s births 1390 deaths Angelic visionaries Injuid-period poets 14th-century Iranian people