HMS Prince Of Wales (53) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Prince of Wales'' was a ''King George V''-class

On 22 May 1941, ''Prince of Wales'', the

On 22 May 1941, ''Prince of Wales'', the  ''Prince of Wales'' fired unopposed until she began a port turn at 05:57, when ''Prinz Eugen'' took her under fire. After ''Hood'' exploded at 06:01, the Germans opened intense and accurate fire on ''Prince of Wales'', with 15-inch, 8-inch and 5.9-inch guns. A heavy hit was sustained below the waterline as ''Prince of Wales'' manoeuvred through the wreckage of ''Hood''. At 06:02, a 15-inch shell struck the starboard side of the compass platform and killed the majority of the personnel there. The navigating officer was wounded, but Captain Leach was unhurt. Casualties were caused by the fragments from the shell's ballistic cap and the material it dislodged in its diagonal path through the compass platform. A 15-inch diving shell penetrated the ship's side below the armour belt amidships, failed to explode and came to rest in the wing compartments on the starboard side of the after boiler rooms. The shell was discovered and defused when the ship was docked at

''Prince of Wales'' fired unopposed until she began a port turn at 05:57, when ''Prinz Eugen'' took her under fire. After ''Hood'' exploded at 06:01, the Germans opened intense and accurate fire on ''Prince of Wales'', with 15-inch, 8-inch and 5.9-inch guns. A heavy hit was sustained below the waterline as ''Prince of Wales'' manoeuvred through the wreckage of ''Hood''. At 06:02, a 15-inch shell struck the starboard side of the compass platform and killed the majority of the personnel there. The navigating officer was wounded, but Captain Leach was unhurt. Casualties were caused by the fragments from the shell's ballistic cap and the material it dislodged in its diagonal path through the compass platform. A 15-inch diving shell penetrated the ship's side below the armour belt amidships, failed to explode and came to rest in the wing compartments on the starboard side of the after boiler rooms. The shell was discovered and defused when the ship was docked at

On 25 October ''Prince of Wales'' and a destroyer escort left home waters bound for

On 25 October ''Prince of Wales'' and a destroyer escort left home waters bound for  At 11:00 that morning the first Japanese air attack began. Eight Type 96 "Nell" bombers dropped their bombs close to ''Repulse'', one passing through the hangar roof and exploding on the 1-inch plating of the main deck below. The second attack force, comprising seventeen "Nells" armed with torpedoes, arrived at 11:30, divided into two attack formations. Despite reports to the contrary, ''Prince of Wales'' was struck by only one torpedo.Garzke, William; Dulin, Robert; Denlay, Kevin: ''Death of a Battleship: The Loss of HMS Prince of Wales. A Marine Forensics Analysis of the Sinking'' https://www.pacificwrecks.com/ships/hms/prince_of_wales/death-of-a-battleship-2012-update.pdf Meanwhile, ''Repulse'' avoided the seven torpedoes aimed at her, as well as bombs dropped by six other "Nells" a few minutes later.

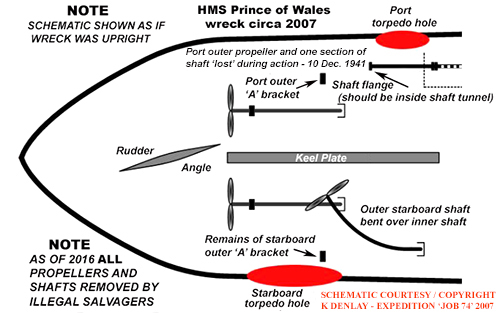

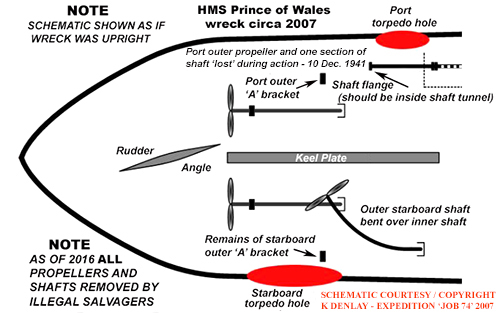

The torpedo struck ''Prince of Wales'' on the port side aft, abaft "Y" Turret, wrecking the outer

At 11:00 that morning the first Japanese air attack began. Eight Type 96 "Nell" bombers dropped their bombs close to ''Repulse'', one passing through the hangar roof and exploding on the 1-inch plating of the main deck below. The second attack force, comprising seventeen "Nells" armed with torpedoes, arrived at 11:30, divided into two attack formations. Despite reports to the contrary, ''Prince of Wales'' was struck by only one torpedo.Garzke, William; Dulin, Robert; Denlay, Kevin: ''Death of a Battleship: The Loss of HMS Prince of Wales. A Marine Forensics Analysis of the Sinking'' https://www.pacificwrecks.com/ships/hms/prince_of_wales/death-of-a-battleship-2012-update.pdf Meanwhile, ''Repulse'' avoided the seven torpedoes aimed at her, as well as bombs dropped by six other "Nells" a few minutes later.

The torpedo struck ''Prince of Wales'' on the port side aft, abaft "Y" Turret, wrecking the outer

The wreck lies upside down in of water at . A Royal Navy White Ensign attached to a line on a buoy tied to a propeller shaft is periodically renewed. The wreck site was designated a 'Protected Place' in 2001 under the

The wreck lies upside down in of water at . A Royal Navy White Ensign attached to a line on a buoy tied to a propeller shaft is periodically renewed. The wreck site was designated a 'Protected Place' in 2001 under the

Link to a wreck survey report compiled after Expedition 'Job 74', May 2007

2012 update analysis of the loss of Prince of Wales, by Garzke, Dulin and Denlay

Description of lower hull indentation damage on wreck of HMS Prince of Wales

SI 2008/0950

Current designation under Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

Navy News 2001

Announcement of designation under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

Link to a 2008 survey report, specifically regarding the stern torpedo damage to PoW.

* *

Newsreel footage of Operation Halberd, as filmed from ''Prince of Wales''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Prince of Wales (53) 1939 ships Battleships sunk by aircraft King George V-class battleships (1939) Maritime incidents in December 1941 Ships built on the River Mersey Military of Singapore under British rule Protected Wrecks of the United Kingdom World War II battleships of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the South China Sea Ships sunk by Japanese aircraft Wreck diving sites Underwater diving sites in Malaysia

battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

that was built at the Cammell Laird

Cammell Laird is a British shipbuilding company. It was formed from the merger of Laird Brothers of Birkenhead and Johnson Cammell & Co of Sheffield at the turn of the twentieth century. The company also built railway rolling stock until 1929, ...

shipyard in Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liver ...

, England. She had an extensive battle history, first seeing action in August 1940 while still being outfitted in her drydock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

when she was attacked and damaged by German aircraft. In her brief career, she was involved in several key actions of the Second World War, including the May 1941 Battle of the Denmark Strait

The Battle of the Denmark Strait was a naval engagement in the Second World War, which took place on 24 May 1941 between ships of the Royal Navy and the ''Kriegsmarine''. The British battleship and the battlecruiser fought the German battlesh ...

where she scored three hits on the German battleship ''Bismarck'', forcing ''Bismarck'' to abandon her raiding mission and head to port for repairs. ''Prince of Wales'' later escorted one of the Malta convoy

The Malta convoys were Allied supply convoys of the Second World War. The convoys took place during the Siege of Malta in the Mediterranean Theatre. Malta was a base from which British sea and air forces could attack ships carrying supplies f ...

s in the Mediterranean, during which she was attacked by Italian aircraft. In her final action, she attempted to intercept Japanese troop convoys off the coast of Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

as part of Force Z

Force Z was a British naval squadron during the Second World War, consisting of the battleship , the battlecruiser and accompanying destroyers. Assembled in 1941, the purpose of the group was to reinforce the British colonial garrisons in the ...

when she was sunk by Japanese aircraft on 10 December 1941, two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

.

She was sunk alongside her consort __NOTOC__

Consort may refer to:

Music

* "The Consort" (Rufus Wainwright song), from the 2000 album ''Poses''

* Consort of instruments, term for instrumental ensembles

* Consort song (musical), a characteristic English song form, late 16th–earl ...

, the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

HMS ''Repulse'', in an attack by 85 Mitsubishi G3M

The was a Japanese bomber and transport aircraft used by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) during World War II.

The Yokosuka L3Y (Allied reporting name "Tina"), was a transport variant of the aircraft manufactured by the Yokosu ...

and G4M bombers of the Japanese navy air service. HMS ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Repulse'' became the first capital ships to be sunk solely by air power on the open sea, a harbinger of the diminishing role this class of ships was subsequently to play in naval warfare. The wreck of ''Prince of Wales'' lies upside down in of water, near Kuantan

Kuantan ( Jawi: ) is a city and the state capital of Pahang, Malaysia. It is located near the mouth of the Kuantan River. Kuantan is the 18th largest city in Malaysia based on 2010 population, and the largest city in the East Coast of Penin ...

, in the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Phil ...

.

Construction

In the aftermath of the First World War, theWashington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

was drawn up in 1922 in an effort to stop an arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and t ...

developing between Britain, Japan, France, Italy and the United States. This treaty limited the number of ships each nation was allowed to build and capped the tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically ref ...

of all capital ships

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

at 35,000 tons. These restrictions were extended in 1930 through the Treaty of London, however, by the mid-1930s Japan and Italy had withdrawn from both of these treaties, and the British became concerned about a lack of modern battleships within their navy. As a result, the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

ordered the construction of a new battleship class: the ''King George V'' class. Due to the provisions of both the Washington Naval Treaty and the Treaty of London, both of which were still in effect when the ''King George V''s were being designed, the main armament of the class was limited to the guns prescribed under these instruments. They were the only battleships built at that time to adhere to the treaty, and even though it soon became apparent to the British that the other signatories to the treaty were ignoring its requirements, it was too late to change the design of the class before they were laid down in 1937.Konstam, p. 20

''Prince of Wales'' was originally to be named ''King Edward VIII'' but upon the abdication of Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

the ship was renamed even before she had been laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

. This occurred at Cammell Laird

Cammell Laird is a British shipbuilding company. It was formed from the merger of Laird Brothers of Birkenhead and Johnson Cammell & Co of Sheffield at the turn of the twentieth century. The company also built railway rolling stock until 1929, ...

's shipyard in Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liver ...

on 1 January 1937, although it was not until 3 May 1939 that she was launched. She was still fitting out when war was declared in September, causing her construction schedule, and that of her sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares one or more parents with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to refer to ...

, , to be accelerated. Nevertheless, the late delivery of gun mountings caused delays in her outfitting.Garzke p. 177

In early August 1940, while she was still being outfitted and was in a semi-complete state, ''Prince of Wales'' was attacked by German aircraft. One bomb fell between the ship and a wet basin wall, narrowly missing a 100-ton dockside crane, and exploded underwater below the bilge keel

A bilge keel is a nautical device used to reduce a ship's tendency to roll. Bilge keels are employed in pairs (one for each side of the ship). A ship may have more than one bilge keel per side, but this is rare. Bilge keels increase hydrodynamic re ...

. The explosion took place about six feet from the ship's port side in the vicinity of the aft group of 5.25-inch guns. Buckling of the shell plating took place over a distance of 20 to , rivets were sprung and considerable flooding took place in the port outboard compartments in the area of damage, causing a ten-degree port list. The flooding was severe, because final compartment air tests had not yet been made and the ship did not have her pumping system in operation.

The water was pumped out through the joint efforts of a local fire company and the shipyard, and ''Prince of Wales'' was later dry-docked for permanent repairs. This damage and the problem with the delivery of her main guns and turrets delayed her completion. As the war progressed there was an urgent need for capital ships, and so her completion was advanced by postponing compartment air tests, ventilation tests and thorough testing of her bilge, ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship, ...

and fuel-oil systems.

Description

''Prince of Wales'' displaced as built and fully loaded. The ship had anoverall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draught of . Her designed metacentric height

The metacentric height (GM) is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the centre of gravity of a ship and its metacentre. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial stab ...

was at normal load and at deep load.

She was powered by Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

geared steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

s, driving four propeller shafts. Steam was provided by eight Admiralty boiler

Three-drum boilers are a class of water-tube boiler used to generate steam, typically to power ships. They are compact and of high evaporative power, factors that encourage this use. Other boiler designs may be more efficient, although bulkier, an ...

s which normally delivered , but could deliver at emergency overload.

This gave ''Prince of Wales'' a top speed of . The ship carried of fuel oil.Garzke, p. 253 She also carried of diesel oil, of reserve feed water and of freshwater. During full-power trials on 31 March 1941, ''Prince of Wales'' at 42,100 tons displacement achieved 28 knots with 111,600 shp at 228 rpm and a specific fuel consumption of 0.73 lb per shp. ''Prince of Wales'' had a range of at .

Armament

''Prince of Wales'' mounted 10 BL 14-inch (356 mm) Mk VII guns. The 14-inch guns were mounted in one Mark II twin turret forward and two Mark III quadruple turrets, one forward and oneaft

"Aft", in nautical terminology, is an adjective or adverb meaning towards the stern (rear) of the ship, aircraft or spacecraft, when the frame of reference is within the ship, headed at the fore. For example, "Able Seaman Smith; lie aft!" or "Wh ...

. The guns could be elevated 40 degrees and depressed 3 degrees. Training arcs were: turret "A", 286 degrees; turret "B", 270 degrees; turret "Y", 270 degrees. Training and elevating was done by hydraulic drives, with rates of two and eight degrees per second, respectively. A full gun broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

weighed , and a salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in one blow and prevent them from fighting b ...

could be fired every 40 seconds. The secondary armament consisted of 16 QF 5.25-inch (133 mm) Mk I guns which were mounted in eight twin mounts, weighing 81 tons each.Garzke, p. 229 The maximum range of the Mk I guns was at a 45-degree elevation, the anti-aircraft ceiling was . The guns could be elevated to 70 degrees and depressed to 5 degrees. The normal rate of fire was ten to twelve rounds per minute, but in practice, the guns could only fire seven to eight rounds per minute

Round or rounds may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* The contour of a closed curve or surface with no sharp corners, such as an ellipse, circle, rounded rectangle, cant, or sphere

* Rounding, the shortening of a number to reduce the numbe ...

. Along with her main and secondary batteries, ''Prince of Wales'' carried 32 QF 2 pdr (1.575-inch, 40.0 mm) Mk.VIII "pom-pom" anti-aircraft guns. She also carried 80 UP projectors, short-range rocket-firing anti-aircraft weapons used in the early days of the Second World War by the Royal Navy.

Operational service

Action with ''Bismarck''

On 22 May 1941, ''Prince of Wales'', the

On 22 May 1941, ''Prince of Wales'', the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

and six destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s were ordered to take station south of Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

and intercept the if she attempted to break out into the Atlantic. Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

John Leach knew that main-battery breakdowns were likely to occur, since Vickers-Armstrongs

Vickers-Armstrongs Limited was a British engineering conglomerate formed by the merger of the assets of Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company in 1927. The majority of the company was nationalised in the 1960s and 1970s, w ...

technicians had already corrected some that took place during training exercises in Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

. These technicians were personally requested by the captain to remain aboard. They did so and played an important role in the resulting action.Garzke pp. 177–79

The next day ''Bismarck'', in company with the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

, was reported heading south-westward in the Denmark Strait

The Denmark Strait () or Greenland Strait ( , 'Greenland Sound') is an oceanic strait between Greenland to its northwest and Iceland to its southeast. The Norwegian island of Jan Mayen lies northeast of the strait.

Geography

The strait connect ...

. At 20:00 Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland

Vice-Admiral Lancelot Ernest Holland, (13 September 1887 – 24 May 1941) was a Royal Navy officer who commanded the British force in the Battle of the Denmark Strait in May 1941 against the German battleship ''Bismarck''. Holland was lost ...

, in his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

''Hood'', ordered the force to steam at , which it did most of the night. His battle plan called for ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Hood'' to concentrate on ''Bismarck'', while the cruisers and would handle ''Prinz Eugen''. However the two cruisers were not informed of this plan because of strict radio silence

In telecommunications, radio silence or Emissions Control (EMCON) is a status in which all fixed or mobile radio stations in an area are asked to stop transmitting for safety or security reasons.

The term "radio station" may include anything cap ...

. At 02:00, on 24 May, the destroyers were sent as a screen to search for the German ships to the north, and at 02:47 ''Hood'' and ''Prince of Wales'' increased speed to and changed course slightly to obtain a better target angle on the German ships. The weather improved, with visibility, and crews were at action stations by 05:10.

At 05:37 an enemy contact report was made, and course was changed to starboard to close range. Neither ship was in good fighting trim. ''Hood'', designed twenty-five years earlier, lacked adequate decking armour and would have to close the range quickly, as she would become progressively less vulnerable to plunging shellfire at shorter ranges. She had completed an overhaul in March and her crew had not been adequately retrained. ''Prince of Wales'', with thicker armour, was less vulnerable to 15-inch shells at ranges greater than , but her crew had also not been trained to battle efficiency. The British ships made their last course change at 05:49, but they had made their approach too fine (the German ships were only 30 degrees on the starboard bow) and their aft

"Aft", in nautical terminology, is an adjective or adverb meaning towards the stern (rear) of the ship, aircraft or spacecraft, when the frame of reference is within the ship, headed at the fore. For example, "Able Seaman Smith; lie aft!" or "Wh ...

turrets could not fire. ''Prinz Eugen'', with ''Bismarck'' astern

This list of ship directions provides succinct definitions for terms applying to spatial orientation in a marine environment or location on a vessel, such as ''fore'', ''aft'', ''astern'', ''aboard'', or ''topside''.

Terms

* Abaft (preposition ...

, had ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Hood'' slightly forward of the beam, and both ships could deliver full broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

s.Garzke p. 179

At 05:53, despite seas breaking over the bows, ''Prince of Wales'' opened fire on ''Bismarck'' at .ADM 234/509 There was some confusion among the British as to which ship was ''Bismarck'' and thirty seconds earlier ''Hood'' had mistakenly opened fire on ''Prinz Eugen'' as the German ships had similar profiles. ''Hood''s first salvo straddled the enemy ship, but ''Prinz Eugen'', in less than three minutes, scored 8-inch-shell hits on ''Hood''. The first shots by ''Prince of Wales'' – two three-gun salvoes at ten-second intervals – were 1,000 yards over. The turret rangefinders on ''Prince of Wales'' could not be used because of spray over the bow and fire was instead directed from the rangefinders in the control tower.Garzke p. 180

The sixth, ninth and thirteenth salvos were straddles and two hits were made on ''Bismarck''. One shell holed her bow and caused ''Bismarck'' to lose 1,000 tons of fuel oil, mostly to salt-water contamination. The other fell short, and entered ''Bismarck'' below her side armour belt, the shell exploded and flooded the auxiliary boiler machinery room and forced the shutdown of two boilers due to a slow leak in the boiler room immediately aft. The loss of fuel and boiler power were decisive factors in the ''Bismarck''s decision to return to port. In ''Prince of Wales'', "A1" gun ceased fire after the first salvo due to a defect. Sporadic breakdowns occurred until the decision to turn away was made, and during the turn "Y" turret jammed.

Both German ships initially concentrated their fire on ''Hood'' and destroyed her with salvoes of 8- and 15-inch shells. An 8-inch shell hit the boat deck and struck a ready service locker for ammunition, and a fire blazed high above the first superstructure deck. At 05:58 at a range of , the force commander ordered a turn of 20 degrees to port to open the range and bring the full battery of the British ships to bear on ''Bismarck''. As the turn began, ''Bismarck'' straddled ''Hood'' with her third and fourth four-gun salvoes and at 06:01 the fifth salvo hit her, causing a large explosion. Flames shot up near ''Hood''s masts, then an orange-coloured fireball and an enormous smoke cloud obliterated the ship. On ''Prince of Wales'', it seemed that ''Hood'' collapsed amidships, and the bow and stern could be seen rising as she rapidly settled. ''Prince of Wales'' made a sharp starboard turn to avoid hitting the debris and in doing so further closed the range between her and the German ships. In the four-minute action, ''Hood'', the largest battlecruiser in the world, had been sunk. 1,419 officers and men were killed. Only three men survived.

''Prince of Wales'' fired unopposed until she began a port turn at 05:57, when ''Prinz Eugen'' took her under fire. After ''Hood'' exploded at 06:01, the Germans opened intense and accurate fire on ''Prince of Wales'', with 15-inch, 8-inch and 5.9-inch guns. A heavy hit was sustained below the waterline as ''Prince of Wales'' manoeuvred through the wreckage of ''Hood''. At 06:02, a 15-inch shell struck the starboard side of the compass platform and killed the majority of the personnel there. The navigating officer was wounded, but Captain Leach was unhurt. Casualties were caused by the fragments from the shell's ballistic cap and the material it dislodged in its diagonal path through the compass platform. A 15-inch diving shell penetrated the ship's side below the armour belt amidships, failed to explode and came to rest in the wing compartments on the starboard side of the after boiler rooms. The shell was discovered and defused when the ship was docked at

''Prince of Wales'' fired unopposed until she began a port turn at 05:57, when ''Prinz Eugen'' took her under fire. After ''Hood'' exploded at 06:01, the Germans opened intense and accurate fire on ''Prince of Wales'', with 15-inch, 8-inch and 5.9-inch guns. A heavy hit was sustained below the waterline as ''Prince of Wales'' manoeuvred through the wreckage of ''Hood''. At 06:02, a 15-inch shell struck the starboard side of the compass platform and killed the majority of the personnel there. The navigating officer was wounded, but Captain Leach was unhurt. Casualties were caused by the fragments from the shell's ballistic cap and the material it dislodged in its diagonal path through the compass platform. A 15-inch diving shell penetrated the ship's side below the armour belt amidships, failed to explode and came to rest in the wing compartments on the starboard side of the after boiler rooms. The shell was discovered and defused when the ship was docked at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

.

At 06:05 Captain Leach decided to disengage and laid down a heavy smokescreen to cover ''Prince of Wales''s escape. Leach then radioed ''Norfolk'' that ''Hood'' had been sunk and went to join ''Suffolk'' astern of ''Bismarck''. The British ships continued to chase ''Bismarck'' until 18:16 when ''Suffolk'' sighted the German battleship at . ''Prince of Wales'' then opened fire on ''Bismarck'' at an extreme range of . All 12 salvos missed. At 01:00 on 25 May ''Prince of Wales'' again regained contact and opened fire at a radar range of , after observers believed that she had scored a hit on ''Bismarck'', ''Prince of Wales''s "A" turret temporarily jammed, leaving her with only six operational guns. After losing ''Bismarck'' owing to poor visibility, and after searching for 12 hours, ''Prince of Wales'' headed for Iceland. Thirteen of her crew had been killed, and nine wounded.

On Friday 6 June, while in dry dock, a hole was found just above the starboard bilge keel

A bilge keel is a nautical device used to reduce a ship's tendency to roll. Bilge keels are employed in pairs (one for each side of the ship). A ship may have more than one bilge keel per side, but this is rare. Bilge keels increase hydrodynamic re ...

. After the inner space had been pumped out, an unexploded shell from ''Bismarck'' was found nose forward, with its fuse, but without a ballistic cap

Armour-piercing, capped, ballistic capped (APCBC) is a type of configuration for armour-piercing ammunition introduced in the 1930s to improve the armour-piercing capabilities of both naval and anti-tank guns. The configuration consists of an ar ...

. The shell was removed by the Bomb Disposal Officer from ''HMS Cochrane

Two ships and a shore establishment of the Royal Navy have borne the name HMS ''Cochrane'', after Admiral Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald:

* was a armoured cruiser launched in 1905. She was stranded in 1918 and broken up.

* HMS ''Cochra ...

''

Atlantic Charter meeting

After repairs at Rosyth, ''Prince of Wales'' took Prime MinisterWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

across the Atlantic for a secret conference with US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

.Chesneau p. 12 On 5 August Roosevelt boarded the cruiser from the presidential yacht

Presidential yacht may refer to a vessel of a country's navy that would be specially used by the country's president. It is common for a vessel to be designated as the presidential yacht during a fleet review.

Some countries (below) have vessels p ...

. ''Augusta'' proceeded from Massachusetts to Placentia Bay

Placentia Bay (french: Baie de Plaisance) is a body of water on the southeast coast of Newfoundland, Canada. It is formed by Burin Peninsula on the west and Avalon Peninsula on the east. Fishing grounds in the bay were used by native people long ...

and Argentia

Argentia ( ) is a Canadian commercial seaport and industrial park located in the Town of Placentia, Newfoundland and Labrador. It is situated on the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula and defined by a triangular shaped headland which r ...

in Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

with the cruiser and five destroyers, arriving on 7 August while the presidential yacht played a decoy role by continuing to cruise New England waters as if the president were still on board. On 9 August, Churchill arrived in the bay aboard ''Prince of Wales'', escorted by the destroyers HMS ''Ripley'', and . At Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, Roosevelt transferred to the destroyer to meet Churchill on board ''Prince of Wales''. The conference continued from 10 to 12 August aboard ''Augusta'' and, at the end of the conference, the Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and ...

was proclaimed. ''Prince of Wales'' arrived back at Scapa Flow on 18 August.

Mediterranean duty

In September 1941, ''Prince of Wales'' was assigned toForce H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

, in the Mediterranean. On 24 September ''Prince of Wales'' formed part of Group II, led by Vice-Admiral Alban Curteis

Admiral (Royal Navy), Admiral Sir Alban Thomas Buckley Curteis Order of the Bath, KCB Royal Victorian Order, CVO Distinguished Service Order, DSO (13 January 1887 – 27 November 1961) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be North America a ...

and consisting of the battleships ''Prince of Wales'' and , the cruisers , , and , and twelve destroyers. The force provided an escort for Operation Halberd

Operation Halberd was a British naval operation that took place on 27 September 1941, during the Second World War. The British were attempting to deliver a convoy from Gibraltar to Malta. The convoy was escorted by several battleships and an air ...

, a supply convoy from Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

to Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

. On 27 September the convoy was attacked by Italian aircraft, with ''Prince of Wales'' shooting down several with her guns. Later that day there were reports that units of the Italian Fleet were approaching. ''Prince of Wales'', the battleship ''Rodney'' and the aircraft carrier were despatched to intercept, but the search proved fruitless. The convoy arrived in Malta without further incident, and ''Prince of Wales'' returned to Gibraltar, before sailing on to Scapa Flow, arriving there on 6 October.

Far East

On 25 October ''Prince of Wales'' and a destroyer escort left home waters bound for

On 25 October ''Prince of Wales'' and a destroyer escort left home waters bound for Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, there to rendezvous with the battlecruiser and the aircraft carrier . ''Indomitable'' however ran aground off Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

a few days later and was unable to proceed. Calling at Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

and Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

South Africa to refuel and generate publicity, ''Prince of Wales'' also stopped in Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

and the Maldive Islands

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

. ''Prince of Wales'' reached Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, on 28 November, joining ''Repulse'' the next day. On 2 December the fleet docked in Singapore. ''Prince of Wales'' then became the flagship of Force Z

Force Z was a British naval squadron during the Second World War, consisting of the battleship , the battlecruiser and accompanying destroyers. Assembled in 1941, the purpose of the group was to reinforce the British colonial garrisons in the ...

, under the command of Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Sir Tom Phillips. Admiral of the Home Fleet Sir John Tovey

Admiral of the Fleet John Cronyn Tovey, 1st Baron Tovey, (7 March 1885 – 12 January 1971), sometimes known as Jack Tovey, was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he commanded the destroyer at the Battle of Jutland and then co ...

was opposed to sending any of the new ''King George V'' battleships as he believed that they were not suited to operating in tropical climates.

Japanese troop-convoys were first sighted on 6 December. Two days later, Japanese aircraft raided Singapore; although the ''Prince of Wales''s anti-aircraft batteries opened fire, they scored no hits and had no effect on the Japanese aircraft. A signal was received from the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

in London ordering the British squadron to commence hostilities, and that evening, confident that a protective air umbrella would be provided by the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

presence in the region, Admiral Phillips set sail. Force Z at this time comprised the battleship ''Prince of Wales'', the battlecruiser ''Repulse'', and the destroyers , , and .Chesneau, pp. 12–13

The object of the sortie was to attack Japanese transports at Kota Bharu

Kota Bharu, colloquially referred to as KB, is a town in Malaysia that serves as the state capital and royal seat of Kelantan. It is situated in the northeastern part of Peninsular Malaysia and lies near the mouth of the Kelantan River.

The t ...

, but in the afternoon of 9 December the Japanese submarine ''I-65'' spotted the British ships, and in the evening they were detected by Japanese aerial reconnaissance. By this time it had been made clear that no RAF fighter support would be forthcoming. At midnight a signal was received that Japanese forces were landing at Kuantan in Malaya. Force Z was diverted to investigate. At 02:11 on 10 December the force was again sighted by a Japanese submarine and at 08:00 arrived off Kuantan, only to discover that the reported landings were a diversion.

propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power and torque and rotation, usually used to connect ...

on that side and destroying bulkheads to one degree or another along the shaft all the way to B Engine Room. This caused rapid uncontrollable flooding and put the entire electrical system in the after part of the ship out of action. Lacking effective damage control, she soon took on a heavy list.Chesneau, p. 13

A third torpedo attack developed against ''Repulse'' and once again she avoided taking any hits.

A fourth attack, conducted by torpedo-carrying Type 1 "Bettys", developed. This one scored hits on ''Repulse'' and she sank at 12:33. Six aircraft from this wave also attacked ''Prince of Wales'', hitting her with three torpedoes, causing further damage and flooding. Finally, a bomb hit ''Prince of Waless catapult deck, penetrated to the main deck, where it exploded, causing many casualties in the makeshift aid centre in the Cinema Flat. Several other bombs from this attack scored very near misses, indenting the hull, popping rivets and causing hull plates to split along the seams and intensifying the flooding. At 13:15 the order to abandon ship was given, and at 13:20 ''Prince of Wales'' capsized to port, floated for a few brief moments upside down, and sank stern first; Admiral Phillips and Captain Leach were among the 327 fatalities.

Aftermath

''Prince of Wales'' and ''Repulse'' were the first capital ships to be sunk solely by naval air power on the open sea (albeit by land-based rather than carrier-based aircraft), a harbinger of the diminishing role this class of ships was to play in naval warfare thereafter. It is often pointed out, however, that contributing factors to the sinking of ''Prince of Wales'' were her surface-scanningradar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

s being inoperable in the humid tropic climate, depriving Force Z of one of its most potent early-warning devices, and the critical early damage she sustained from the first torpedo. Another factor which led to ''Prince of Wales''s demise was the loss of her dynamo

file:DynamoElectricMachinesEndViewPartlySection USP284110.png, "Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator (electric), commutator. Dynamos were the f ...

s, depriving ''Prince of Wales'' of many of her electric pumps. Further electrical failures left parts of the ship in total darkness, and added to the difficulties of her damage repair parties as they attempted to counter the flooding.

The sinking was the subject of an inquiry chaired by Mr. Justice Bucknill, but the true causes of the ship's loss were only established when divers examined the wreck after the war. The Director of Naval Construction's report on the sinking claimed that the ship's anti-aircraft guns could have inflicted heavy casualties before torpedoes were dropped, if not preventing the successful conclusion of attack had crews been more adequately trained in their operation.

The wreck

The wreck lies upside down in of water at . A Royal Navy White Ensign attached to a line on a buoy tied to a propeller shaft is periodically renewed. The wreck site was designated a 'Protected Place' in 2001 under the

The wreck lies upside down in of water at . A Royal Navy White Ensign attached to a line on a buoy tied to a propeller shaft is periodically renewed. The wreck site was designated a 'Protected Place' in 2001 under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

Protection is any measure taken to guard a thing against damage caused by outside forces. Protection can be provided to physical objects, including organisms, to systems, and to intangible things like civil and political rights. Although th ...

, just prior to the 60th anniversary of her sinking. The ship's bell

A ship's bell is a bell on a ship that is used for the indication of time as well as other traditional functions. The bell itself is usually made of brass or bronze, and normally has the ship's name engraved or cast on it.

Strikes Timing of s ...

was manually raised in 2002 by British technical divers with the permission of the Ministry of Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

and blessing of the Force Z Survivors Association. It was restored, then presented for display by First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed ...

and Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral Sir Alan West, to the Merseyside Maritime Museum

The Merseyside Maritime Museum is a museum based in the city of Liverpool, Merseyside, England. It is part of National Museums Liverpool and an Anchor Point of ERIH, The European Route of Industrial Heritage. It opened for a trial season in 198 ...

in Liverpool. The bell has been since moved to the National Museum of the Royal Navy

The National Museum of the Royal Navy was created in early 2009 to act as a single non-departmental public body for the museums of the Royal Navy. With venues across the United Kingdom, the museums detail the history of the Royal Navy operating o ...

at the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard

Portsmouth Historic Dockyard is an area of HM Naval Base Portsmouth which is open to the public; it contains several historic buildings and ships. It is managed by the National Museum of the Royal Navy as an umbrella organization representing f ...

for display in the Hear My Story Galleries.

In May 2007, Expedition 'Job 74', a dedicated survey of the exterior hull of both ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Repulse'', was conducted. The expedition's findings sparked considerable interest among naval architects and marine engineers around the world; as they detailed the nature of the damage to ''Prince of Wales'' and the exact location and number of torpedo hits. Consequently, the findings contained in the initial expedition report and later supplementary reports were analysed by the SNAME (Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers) Marine Forensics Committee and a resultant paper was drawn up entitled ''Death of a Battleship: A Re-analysis of the Tragic Loss of HMS Prince of Wales'', and was subsequently presented at a meeting of RINA (Royal Institution of Naval Architects) and IMarEST (Institute of Marine Engineering, Science & Technology) members in London in 2009 by Mr William Garzke. This report was also presented to the IMarEST, this time in New York, in 2011. However, in 2012 the original paper was updated and expanded (and renamed ''Death of a Battleship: The Loss of HMS Prince of Wales. A Marine Forensics Analysis of the Sinking'') in light of a subsequent diver being able to penetrate deep into the port outer propeller shaft tunnel with a high definition camera, taking photos along the entire length of the propeller shaft all the way to the aft bulkhead of 'B' Engine Room.

In October 2014, the ''Daily Telegraph'' reported that both ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Repulse'' were being "extensively damaged" with explosives by scrap metal dealers.

It is currently traditional for every passing Royal Navy ship to perform a remembrance service over the site of the wrecks.

Replica bell for successor

In spring 2019, Cammell Laird was commissioned to make a replica of the ship's bell for the ship's successor, , the second . The original at the National Museum of the Royal Navy's Portsmouth Historic Dockyard location was surveyed as part of the process. Cammell Laird were able to contact Utley Offshore in St Helens, the foundry that made both the original bell and 's bell, who still had the original pattern based on the 1908 Admiralty design. Compared to the bronze or bell metal that is used in most modern ship bells, specially sourced nickel silver was used for authenticity. The engraving was done by Shawcross in Birkenhead, while Cammell Laird shipwrights constructed the hardwood base. Cammell Laird COO Tony Graham presented the finished replica to commanding officer Captain Darren Houston during the ship's week-long visit to Liverpool in March 2020.Refits

During her career, ''Prince of Wales'' was refitted on several occasions, to bring her equipment up to date. The following are the dates and details of the refits undertaken.Chesneau p. 52References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * Hein, David. "Vulnerable: HMS ''Prince of Wales'' in 1941". ''Journal of Military History'' 77, no. 3 (July 2013): 955–989. Abstract online: http://www.smh-hq.org/jmh/jmhvols/773.html * Horodyski, Joseph M. ''Military Heritage'' 3, no. 3 (December 2001): 69–77. * * * * * * * *Web

Link to a wreck survey report compiled after Expedition 'Job 74', May 2007

2012 update analysis of the loss of Prince of Wales, by Garzke, Dulin and Denlay

Description of lower hull indentation damage on wreck of HMS Prince of Wales

SI 2008/0950

Current designation under Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

Navy News 2001

Announcement of designation under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

Link to a 2008 survey report, specifically regarding the stern torpedo damage to PoW.

* *

External links

* ttp://www.forcez-survivors.org.uk/biographies/listprincecrew.html List of CrewNewsreel footage of Operation Halberd, as filmed from ''Prince of Wales''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Prince of Wales (53) 1939 ships Battleships sunk by aircraft King George V-class battleships (1939) Maritime incidents in December 1941 Ships built on the River Mersey Military of Singapore under British rule Protected Wrecks of the United Kingdom World War II battleships of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the South China Sea Ships sunk by Japanese aircraft Wreck diving sites Underwater diving sites in Malaysia