HMS Penelope (97) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Penelope'' was an light cruiser of the

She left Malta, again with ''Breconshire'' on 13 February 1942 and an eastbound convoy aided by six destroyers, Operation MG5, returning to Malta on 15 February, with the destroyers and . On 23 March, she left Malta with ''Legion'' for Operation MG1, a further convoy to Malta. ''Breconshire'' was hit and taken in tow by ''Penelope'' and was later safely secured to a buoy in

She left Malta, again with ''Breconshire'' on 13 February 1942 and an eastbound convoy aided by six destroyers, Operation MG5, returning to Malta on 15 February, with the destroyers and . On 23 March, she left Malta with ''Legion'' for Operation MG1, a further convoy to Malta. ''Breconshire'' was hit and taken in tow by ''Penelope'' and was later safely secured to a buoy in

The damage was extensive and required several months at home after temporary repairs in Gibraltar. The ship was visited by the

The damage was extensive and required several months at home after temporary repairs in Gibraltar. The ship was visited by the

/ref> She has made reference to this fact in the House of Commons.

* ttp://www.world-war.co.uk/index.php3 HMS Penelope - WW2 Cruisers

IWM Interview with survivor Walter Pettyfer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Penelope (97) Arethusa-class cruisers (1934) Ships built in Belfast 1935 ships World War II cruisers of the United Kingdom Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea Maritime incidents in February 1944 Ships built by Harland and Wolff

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. She was built by Harland & Wolff (Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

); her keel was laid down on 30 May 1934. She was launched on 15 October 1935, and commissioned 13 November 1936. She was torpedoed and sunk by German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

U-410 near Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

with great loss of life on 18 February 1944. On wartime service with Force K

Force K was the name given to three British Royal Navy groups of ships during the Second World War. The first Force K operated from West Africa in 1939, to intercept commerce raiders. The second Force K was formed in October 1941 at Malta, to op ...

, she was holed so many times by bomb fragments that she acquired the nickname "HMS ''Pepperpot''".

History

Home Fleet

At the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

''Penelope'' was with the 3rd Cruiser Squadron in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

, having arrived at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

on 2 September 1939. ''Penelope'' and her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

were reallocated to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron in the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

and arrived at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

on 11 January 1940. On 3 February she left for the River Clyde

The River Clyde ( gd, Abhainn Chluaidh, , sco, Clyde Watter, or ) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. It is the ninth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the third-longest in Scotland. It runs through the major cit ...

en route to Rosyth, arrived on 7 February and operated with the 2nd Cruiser Squadron on convoy escort duties. In April and May 1940, she took part in the Norwegian Campaign.

On 11 April ''Penelope'' ran aground off Fleinvær while hunting German merchant ships entering the Vestfjord

Vestfjord, meaning "West Fjord" in the Danish language, is a fjord in King Christian X Land, eastern Greenland.

This fjord is part of the Scoresby Sound system in the area of Sermersooq municipality. Geography

This tributary fjord extends between ...

. Her boiler room was flooded and she was holed forward. The destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

towed her to Skjelfjord where an advanced base had been improvised. Despite air attacks, temporary repairs were made and she was towed home a month later. She arrived at Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

in Scotland on 16 May 1940 where additional temporary repairs were carried out, before proceeding on 19 August to the Tyne for permanent repairs.

After repairs and trials were completed in August 1941, ''Penelope'' reappeared as 'a new ship from the water line down'. She returned to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

on 17 August 1941. On 9 September she left Greenock escorting the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

to Rosyth. Later that month she was employed in patrolling the Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

–Faroes

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway betw ...

passage to intercept enemy surface ships.

On 6 October 1941 ''Penelope'' left Hvalfjord, Iceland, with another battleship, , escorting the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

for the successful Operation E. J., an air attack on German shipping between Glom Fjord and the head of West Fjord, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. The force returned to Scapa Flow on 10 October 1941.

Force K

''Penelope'' and her sister were then assigned to form the core ofForce K

Force K was the name given to three British Royal Navy groups of ships during the Second World War. The first Force K operated from West Africa in 1939, to intercept commerce raiders. The second Force K was formed in October 1941 at Malta, to op ...

based at Malta and departed Scapa on 12 October 1941, arriving in Malta on 21 October. On 8 November, both cruisers and their escorting destroyers sailed from Malta to intercept an Italian convoy of six destroyers and seven merchant ships sailing for Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

, which had been sighted by aircraft at 37°53'N – 16°36'E. During the ensuing Battle of the Duisburg Convoy on 9 November off Cape Spartivento

Domus de Maria is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of South Sardinia in the Italian region Sardinia, located about southwest of Cagliari.

Domus de Maria borders the following municipalities: Pula, Santadi, and Teulada.

See also ...

, the British sank one enemy destroyer () and all of the merchant ships.

On 23 November, Force K sailed again to intercept another enemy convoy; next day they sank two more merchant ships west of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. Force K received the Prime Minister's congratulations on their fine work. On 1 December 1941, Force K sank the Italian merchant vessel ''Adriatico'', at 32°52'N – 2°30'E, the destroyer ''Alvise da Mosto'', and the tanker ''Iridio Mantovani'' at 33°45'N – 12°30'E. The First Sea Lord congratulated them on 3 December.

On 19 December, while operating off Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

, ''Penelope'' struck a mine but was not seriously damaged, although the cruiser and the destroyer were sunk by mines in the same action. ''Penelope'' was sent into the dockyard for repairs and returned to service at the beginning of January 1942. On 5 January, she left Malta with Force K, escorting the Special Service Vessel ''Glengyle'' to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

(Operation ME9), returning on 27 January, escorting the supply ship ''Breconshire''.

She left Malta, again with ''Breconshire'' on 13 February 1942 and an eastbound convoy aided by six destroyers, Operation MG5, returning to Malta on 15 February, with the destroyers and . On 23 March, she left Malta with ''Legion'' for Operation MG1, a further convoy to Malta. ''Breconshire'' was hit and taken in tow by ''Penelope'' and was later safely secured to a buoy in

She left Malta, again with ''Breconshire'' on 13 February 1942 and an eastbound convoy aided by six destroyers, Operation MG5, returning to Malta on 15 February, with the destroyers and . On 23 March, she left Malta with ''Legion'' for Operation MG1, a further convoy to Malta. ''Breconshire'' was hit and taken in tow by ''Penelope'' and was later safely secured to a buoy in Marsaxlokk

Marsaxlokk () is a small, traditional fishing village in the South Eastern Region of Malta. It has a harbour, and is a tourist attraction known for its views, fishermen and history. As at March 2014, the village had a population of 3,534. The ...

harbour, the whole operation was under the charge of ''Penelope''s commanding officer, Captain A. D. Nicholl, of whose work the Naval Officer In Command (NOIC), Malta expressed appreciation.

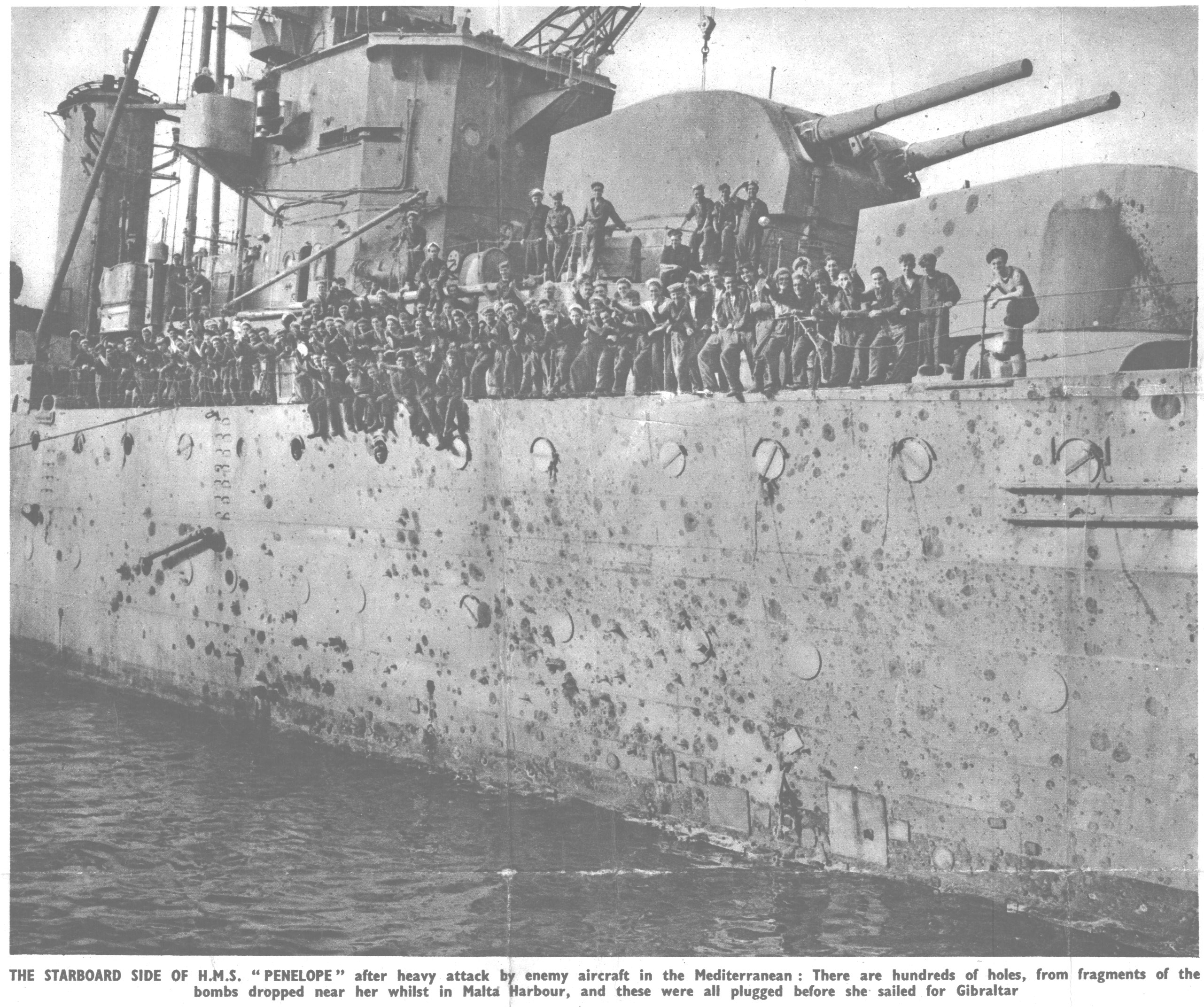

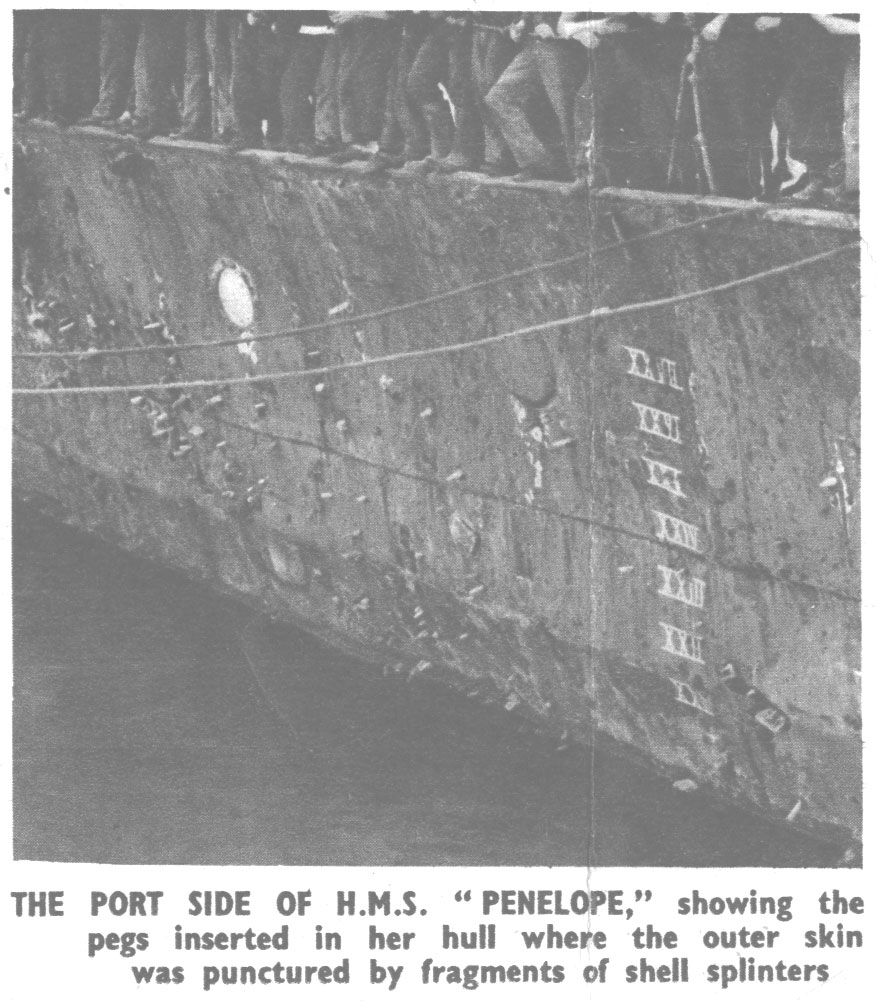

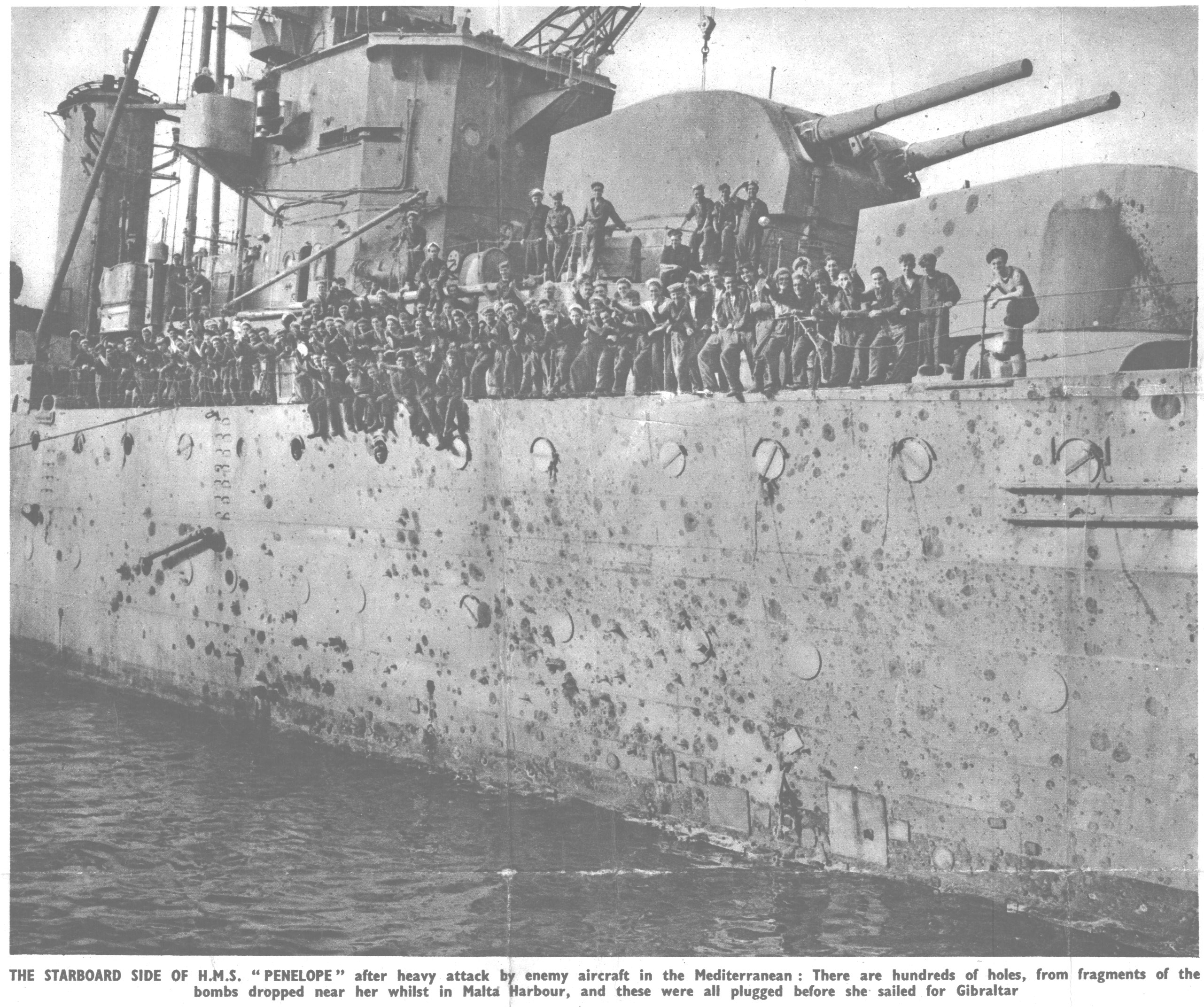

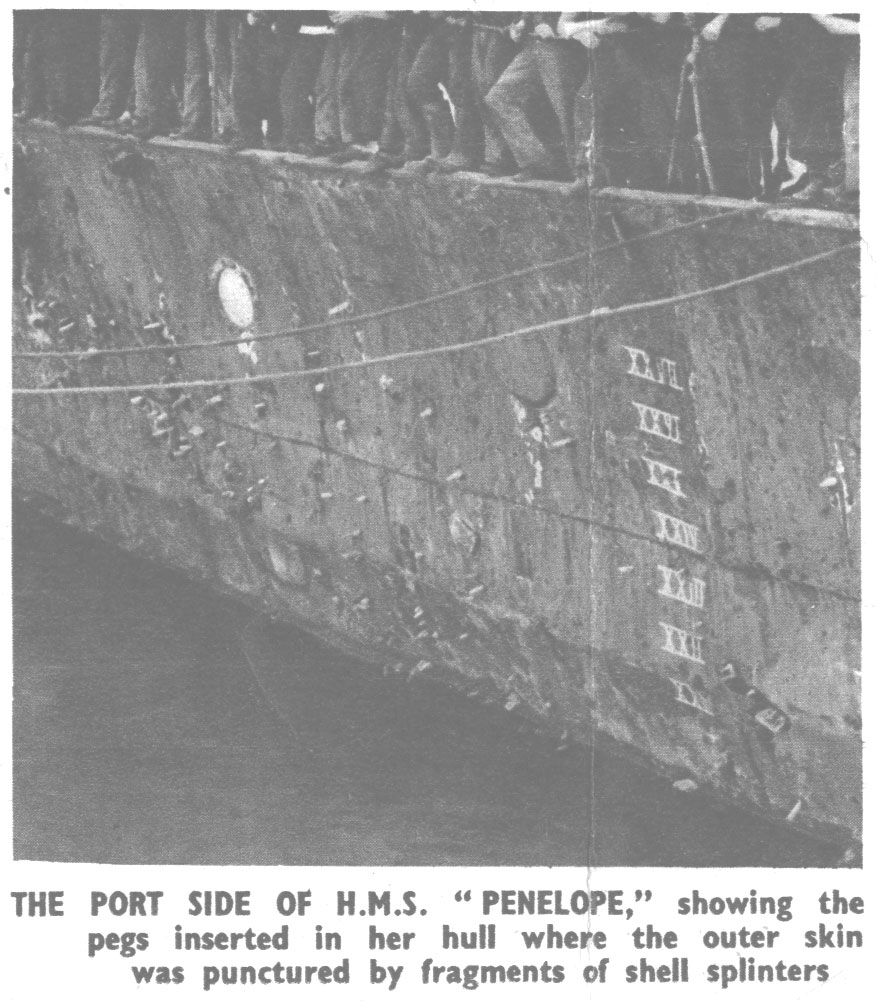

''Penelope'' was holed both forward and aft by near-misses during air attacks on Malta on 26 March. While in the island, she was docked and repaired at the Malta Dry Docks. Day after day she was attacked by German aircraft and the crew worked to fix a myriad of shrapnel holes, so many that she was nicknamed HMS ''Pepperpot''; when these had been plugged with long pieces of wood, HMS ''Porcupine''. ''Penelope'' gun-loader, Albert Hewitt, was blown off his feet but regained consciousness still safely holding a four inch shell. ''Penelope'' sailed for Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

on 8 April and on the next day was repeatedly attacked from the air. She arrived in Gibraltar on 10 April, with further damage from near-misses. Later that day she received a signal from Vice Admiral, Malta, "True to your usual form. Congratulations".

Repairs and awards

The damage was extensive and required several months at home after temporary repairs in Gibraltar. The ship was visited by the

The damage was extensive and required several months at home after temporary repairs in Gibraltar. The ship was visited by the Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester () is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curren ...

on 11 April, who had originally laid down her keel plate. The duke also visited Captain Nicholl in hospital. The First Sea Lord congratulated the ship on her successful arrival in Gibraltar. The question of ''Penelope''s repairs had been reconsidered, and it was decided to send her to the United States. She accordingly left Gibraltar on 10 May 1942, for the Navy Yard at New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

via Bermuda, arriving on 19 May. She was under repair until September and arrived in Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

on 15 September, proceeding, again via Bermuda, to Portsmouth, England, which she reached on 1 October 1942. The King, at an investiture at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

, decorated 21 officers and men from ''Penelope'' as "Heroes of Malta". Among their awards were two Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

s, a Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

and two Distinguished Service Medals.

Western Mediterranean

''Penelope'' arrived at Scapa Flow on 2 December and remained in home waters until the middle of January 1943. She left the Clyde on 17 January for Gibraltar, where she arrived on 22 January. She had been allocated to the 12th Cruiser Squadron, in which she operated with the Western Mediterranean Fleet under the flag of Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham during the follow-up of OperationOperation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

, the landings in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

.

On 1 June 1943, ''Penelope'' and the destroyers and shelled the Italian island of Pantelleria. The force received enemy gunfire in return and ''Penelope'' was hit once but suffered little damage. On 8 June 1943, with the cruiser and other ships, she took part in a further heavy bombardment of the island. A demand for its surrender was refused. The same force left Malta on 10 June, to cover the assault (Operation Corkscrew

Operation Corkscrew was the codename for the Allied invasion of the Italian island of Pantelleria (between Sicily and Tunisia) on 11 June 1943, prior to the Allied invasion of Sicily, during the Second World War. There had been an early plan to ...

), which resulted in the surrender of the island on 11 June 1943. On 11 and 12 June ''Penelope'' also took part in the attack on Lampedusa

Lampedusa ( , , ; scn, Lampidusa ; grc, Λοπαδοῦσσα and Λοπαδοῦσα and Λοπαδυῦσσα, Lopadoûssa; mt, Lampeduża) is the largest island of the Italian Pelagie Islands in the Mediterranean Sea.

The ''comune'' of L ...

, which fell to the British forces on 12 June 1943.

On 10 July 1943, with ''Aurora'' and two destroyers, ''Penelope'' carried out a diversionary bombardment of Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also by ...

as part of the conquest of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, (Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily). The flotilla then moved to Taormina

Taormina ( , , also , ; scn, Taurmina) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Messina, on the east coast of the island of Sicily, Italy. Taormina has been a tourist destination since the 19th century. Its beaches on ...

where the railway station was shelled. On 11 July, ''Penelope'' left Malta with the 12th Cruiser Squadron as part of Force H to provide cover for the northern flank of the assault on Sicily. During the remainder of July and August, she took part in various other naval gunfire support and sweeps during the campaign for Sicily.

Force Q

On 9 September 1943, ''Penelope'' was part of Force Q forOperation Avalanche

Operation Avalanche was the codename for the Allied landings near the port of Salerno, executed on 9 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II. The Italians withdrew from the war the day before the invasion, but ...

, the allied landings at Salerno, Italy, during which she augmented the bombardment force. ''Penelope'' left the Salerno area on 26 September with ''Aurora'' and at the beginning of October was transferred to the Levant in view of a possible attack on the island of Kos in the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

. On 7 October, with the cruiser and other ships, she sank six enemy landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. Pr ...

, one ammunition ship and an armed trawler off Stampalia

Astypalaia (Greek: Αστυπάλαια, ), is a Greek island with 1,334 residents (2011 census). It belongs to the Dodecanese, an archipelago of fifteen major islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea.

The island is long, wide at the most, an ...

. While the ships were retiring through the Scarpanto Straits south of Rhodes, they were attacked by 18 Ju 87 "Stuka" dive-bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact through ...

s of I Gruppe Sturzkampfgeschwader 3

''Sturzkampfgeschwader 3'' (StG 3—Dive Bomber Wing 3) was a Dive bomber Wing (air force unit), wing in the German ''Luftwaffe'' during World War II and operated the Junkers Ju 87 ''Stuka''.

The wing was activated on 9 July 1940 using personne ...

MEGARA. Although damaged by a bomb, ''Penelope'' was able to return to Alexandria at . On 19 November 1943 the ship moved to Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

in connection with possible developments in the Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

situation. Towards the end of 1943, she was ordered to Gibraltar for Operation Stonewall

Operation Stonewall was a World War II operation to intercept blockade runners off the west coast of German-occupied France. It was an effective example of inter-service and international co-operation.

Background

From the start of the war, the ...

, (anti-blockade-runner duties), in the Atlantic. On 27 December, the forces in this operation destroyed the German blockade-runner ''Alsterufer'' which was sunk by aircraft co-operating with Royal Navy ships. ''Penelope'' returned to Gibraltar on 30 December and took part in Operation Shingle, the amphibious assault on Anzio

Anzio (, also , ) is a town and ''comune'' on the coast of the Lazio region of Italy, about south of Rome.

Well known for its seaside harbour setting, it is a Port, fishing port and a departure point for ferries and hydroplanes to the Pontine I ...

, Italy, providing gunfire support as part of Force X with on 22 January 1944. She also assisted in the bombardments in the Formia area during the later operations. She made eight shoots on 8 February.

Sinking

On 18 February 1944, ''Penelope'', under the command of Captain G. D. Belben, was leavingNaples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

to return to the Anzio area when she was torpedoed at by the under the command of Horst-Arno Fenski. A torpedo struck her in the after engine room and was followed sixteen minutes later by another torpedo that hit in the after boiler room, causing her immediate sinking; 417 of the crew, including the captain, went down with the ship and 206 survived. A memorial plaque commemorating those lost is in St Ann's Church, HM Dockyard, Portsmouth.

Cultural References

''The Ship''

C. S. Forester

Cecil Louis Troughton Smith (27 August 1899 – 2 April 1966), known by his pen name Cecil Scott "C. S." Forester, was an English novelist known for writing tales of naval warfare, such as the 12-book Horatio Hornblower series depicting a Roya ...

, author of the Horatio Hornblower

Horatio Hornblower is a fictional officer in the British Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, the protagonist of a series of novels and stories by C. S. Forester. He later became the subject of films, radio and television programmes, an ...

series of sea stories

Nautical fiction, frequently also naval fiction, sea fiction, naval adventure fiction or maritime fiction, is a genre of literature with a setting on or near the sea, that focuses on the human relationship to the sea and sea voyages and highligh ...

set at the time of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, published his novel ''The Ship'' in May 1943. It is set in the war in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

and follows a Royal Navy light cruiser in an action where it defeats a superior Italian force. The character and motivation of many of the men on board and the contributions they make are considered. The author dedicated the book "with the deepest respect to the officers and crew of HMS ''Penelope''". The story of the fictional HMS ''Artemis'' is based on but does not follow in detail, the Second Battle of Sirte

The Second Battle of Sirte (on 22 March 1942) was a naval engagement in the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Gulf of Sidra and southeast of Malta, during the Second World War. The escorting warships of a British convoy to Malta held off a much ...

. The book was published before ''Penelope'' was sunk.

Penelope Mordaunt

Penny Mordaunt, the Defence Secretary of the United Kingdom for 85 days in 2019, is named after HMS ''Penelope''.bbc.com 2 May 2019/ref> She has made reference to this fact in the House of Commons.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

* The book describes in detail the missions of I.StG 3 against British forces in the Aegean sea in 1943. *External links

** ttp://www.world-war.co.uk/index.php3 HMS Penelope - WW2 Cruisers

IWM Interview with survivor Walter Pettyfer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Penelope (97) Arethusa-class cruisers (1934) Ships built in Belfast 1935 ships World War II cruisers of the United Kingdom Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea Maritime incidents in February 1944 Ships built by Harland and Wolff