HMS Monarch (1911) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Monarch'' was the second of four

The ''Orion'' class was equipped with 10 breech-loading (BL) Mark V guns in five hydraulically powered twin-

The ''Orion'' class was equipped with 10 breech-loading (BL) Mark V guns in five hydraulically powered twin-

Repeated reports of submarines in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to conclude that the defences there were inadequate and he ordered that the Grand Fleet be dispersed to other bases until the defences be reinforced. On 16 October the 2nd BS was sent to

Repeated reports of submarines in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to conclude that the defences there were inadequate and he ordered that the Grand Fleet be dispersed to other bases until the defences be reinforced. On 16 October the 2nd BS was sent to

The Grand Fleet conducted another fruitless sweep of the North Sea in late December and, while trying to enter Scapa Flow in a Force 8

The Grand Fleet conducted another fruitless sweep of the North Sea in late December and, while trying to enter Scapa Flow in a Force 8

dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

s built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in the early 1910s. She spent the bulk of her career assigned to the Home

A home, or domicile, is a space used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for one or many humans, and sometimes various companion animals. It is a fully or semi sheltered space and can have both interior and exterior aspects to it. H ...

and Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

s. Aside from participating in the failed attempt to intercept the German ships that had bombarded Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in late 1914, the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

in May 1916 and the inconclusive action of 19 August, her service during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

.

After the Grand Fleet was dissolved in early 1919, ''Monarch'' was transferred to back to the Home Fleet for a few months before she was assigned to the Reserve Fleet

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; a ...

. The ship was listed for disposal in mid-1922, but was hulked for use as a stationary training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

. In late 1923 ''Monarch'' was converted into a target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammuniti ...

and was sunk in early 1925.

Design and description

The ''Orion''-class ships were designed in response to the beginning of theAnglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship that ...

and were much larger than their predecessors of the to accommodate larger, more powerful guns and heavier armour. In recognition of these improvements, the class was sometimes called "super-dreadnoughts". The ships had an overall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a deep draught of . They displaced at normal load and at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

as built; by 1918 ''Monarch''s deep displacement had increased to . Her crew numbered 738 officers and ratings upon completion and 750 as of 1914.Burt, p. 136

The ''Orion'' class was powered by two sets of Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

direct-drive

A direct-drive mechanism is a mechanism design where the force or torque from a prime mover is transmitted directly to the effector device (such as the drive wheels of a vehicle) without involving any intermediate couplings such as a gear train or ...

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

s, each driving two shafts, using steam provided by 18 Yarrow boiler

Yarrow boilers are an important class of high-pressure water-tube boilers. They were developed by

Yarrow & Co. (London), Shipbuilders and Engineers and were widely used on ships, particularly warships.

The Yarrow boiler design is characteristic ...

s. The turbines were rated at and were intended to give the battleships a speed of .Parkes, p. 525 During her sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s on 9 December 1911, ''Monarch'' reached a maximum speed of from . The ships carried enough coal and fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

to give them a range of at a cruising speed of .

Armament and armour

The ''Orion'' class was equipped with 10 breech-loading (BL) Mark V guns in five hydraulically powered twin-

The ''Orion'' class was equipped with 10 breech-loading (BL) Mark V guns in five hydraulically powered twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, all on the centreline. The turrets were designated 'A', 'B', 'Q', 'X' and 'Y', from front to rear. Their secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of 16 BL Mark VII guns. These guns were split evenly between the forward and aft superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

, all in single mounts. Four 3-pounder () saluting gun

A salute is usually a formal hand gesture or other action used to display respect in military situations. Salutes are primarily associated with the military and law enforcement, but many civilian organizations, such as Girl Guides, Boy Sco ...

s were also carried. The ships were equipped with three 21-inch (533 mm) submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one on each broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

and another in the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

, for which 20 torpedoes were provided.

The ''Orion''s were protected by a waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

armoured belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating t ...

that extended between the end barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s. Their decks ranged in thickness between and 4 inches with the thickest portions protecting the steering gear in the stern. The main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

turret faces were thick, and the turrets were supported by barbettes.

Modifications

In 1914 the shelter-deck guns were enclosed incasemates

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" mea ...

Friedman, p. 123 and a fire-control director was installed sometime in 1914, before August, on a platform below the spotting top

Spotting may refer to:

Medicine

* Vaginal spotting, light bleeding that is not a menstrual period

Photography:

* Aircraft spotting

* Bus spotting

* Car spotting

* Train spotting

Pastimes:

* Spots (cannabis), a method of smoking cannabis

Phys ...

. By October 1914, a pair of anti-aircraft (AA) guns had been installed. Additional deck armour was added after the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. Around the same time, three 4-inch guns were removed from the aft superstructure and the ship was modified to operate kite balloon

A kite balloon is a tethered balloon which is shaped to help make it stable in low and moderate winds and to increase its lift. It typically comprises a streamlined envelope with stabilising features and a harness or yoke connecting it to the mai ...

s. A flying-off platform

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the Deck (ship), surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the Helicopter deck ...

was mounted on 'B' turret's roof and extended onto the gun barrels during 1917–1918. A high-angle rangefinder was fitted in the forward superstructure by 1921.

Construction and career

''Monarch'', named after athird-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

, ''Monarque'', that had been captured from the French in 1747,Silverstone, p. 252 was the third ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy. The ship was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

by Armstrong Whitworth

Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd was a major British manufacturing company of the early years of the 20th century. With headquarters in Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, Armstrong Whitworth built armaments, ships, locomotives, automobiles and a ...

at their shipyard in Elswick on 1 April 1910 and launched on 30 March 1911.Preston, p. 28 She was completed on 31 March 1912, commissioned with a partial crew on 16 April and fully commissioned on 27 April. Including her armament, her cost is variously quoted at £1,888,736 or £1,886,912. ''Monarch'' was assigned to the 2nd division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

of the Home Fleet which was redesignated as the 2nd Battle Squadron (BS) on 1 May.Burt, p. 146 The ship, together with her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

s and , participated in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

. They then participated in training manoeuvres. The three sisters were present with the 2nd BS to receive the President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

, Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (, ; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France.

Trained in law, Poincaré was elected deputy in 1 ...

, at Spithead on 24 June 1913 and then participated in the annual fleet manoeuvres in August.Burt, pp. 146, 148, 150

World War I

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, ''Monarch'' took part in a testmobilisation

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

and fleet review as part of the British response to the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I (1914–1918). The crisis began on 28 June 1 ...

. Arriving in Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

on 25 July, she was ordered to proceed with the rest of the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

four days later to safeguard the fleet from a possible surprise attack by the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

. Following the outbreak of World War I in August, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

, and placed under the command of Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Sir John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutlan ...

. On 8 August, ''Monarch'' was conducting gunnery practice south-east of Fair Isle

Fair Isle (; sco, Fair Isle; non, Friðarey; gd, Fara) is an island in Shetland, in northern Scotland. It lies about halfway between mainland Shetland and Orkney. It is known for its bird observatory and a traditional style of knitting. Th ...

when she was unsuccessfully attacked by a submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

-fired torpedo. This was probably a false alarm as the area was too far to the west of the German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s' patrol zones to be likely. , however, has been suggested as a candidate for the attack, although the boat was sunk the following day with the loss of all hands and the truth will never be known.

Repeated reports of submarines in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to conclude that the defences there were inadequate and he ordered that the Grand Fleet be dispersed to other bases until the defences be reinforced. On 16 October the 2nd BS was sent to

Repeated reports of submarines in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to conclude that the defences there were inadequate and he ordered that the Grand Fleet be dispersed to other bases until the defences be reinforced. On 16 October the 2nd BS was sent to Loch na Keal

Loch na Keal ( gd, Loch na Caol), meaning Loch of the Kyle, or Narrows, also Loch of the Cliffs, is the principal sea loch on the western, or Atlantic coastline of the island of Mull, in the Inner Hebrides, Argyll and Bute, Scotland. Loch na Keal ...

on the western coast of Scotland. The squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

departed for gunnery practice off the northern coast of Ireland on the morning of 27 October and the dreadnought struck a mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

* Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

...

, laid a few days earlier by the German armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

. Thinking that the ship had been torpedoed by a submarine, the other dreadnoughts were ordered away from the area, while smaller ships rendered assistance. On the evening of 22 November 1914, the Grand Fleet conducted a fruitless sweep in the southern half of the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

; ''Monarch'' stood with the main body in support of Vice-Admiral David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back in port in Scapa Flow by 27 November.

Bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

The Royal Navy'sRoom 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (old building; officially part of NID25), was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the ...

had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans for a German attack on Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, su ...

, Hartlepool

Hartlepool () is a seaside and port town in County Durham, England. It is the largest settlement and administrative centre of the Borough of Hartlepool. With an estimated population of 90,123, it is the second-largest settlement in County ...

and Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in the Scarborough borough of North Yorkshire, England. Situated on the east coast of Yorkshire at the mouth of the River Esk, Whitby has a maritime, mineral and tourist heritage. Its East Clif ...

in mid-December using the four battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

s of ''Konteradmiral

''Konteradmiral'', abbreviated KAdm or KADM, is the second lowest naval flag officer rank in the German Navy. It is equivalent to '' Generalmajor'' in the '' Heer'' and ''Luftwaffe'' or to '' Admiralstabsarzt'' and ''Generalstabsarzt'' in the '' ...

'' (Rear-Admiral) Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Franz von Hipper joined the German Navy in 1881 as an officer cadet. He commanded several torpedo boat units an ...

's I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

. The radio messages did not mention that the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

with fourteen dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, prote ...

s would reinforce Hipper. The ships of both sides departed their bases on 15 December, with the British intending to ambush the German ships on their return voyage. They mustered the six dreadnoughts of Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender's 2nd BS, including ''Monarch'' and her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

s, ''Orion'' and ''Conqueror'', and Beatty's four battlecruisers.

The screening forces of each side blundered into each other during the early morning darkness and heavy weather of 16 December. The Germans got the better of the initial exchange of fire, severely damaging several British destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s, but Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Friedrich von Ingenohl (30 June 1857 – 19 December 1933) was a German admiral from Neuwied best known for his command of the German High Seas Fleet at the beginning of World War I.

He was the son of a tradesman. H ...

, commander of the High Seas Fleet, ordered his ships to turn away, concerned about the possibility of a massed attack by British destroyers in the dawn's light. A series of miscommunications and mistakes by the British allowed Hipper's ships to avoid an engagement with Beatty's forces.

1915–1916

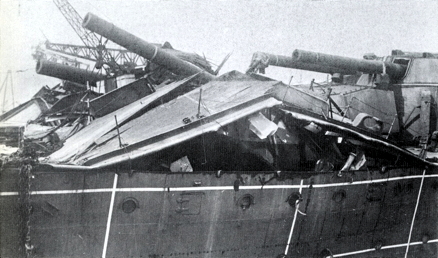

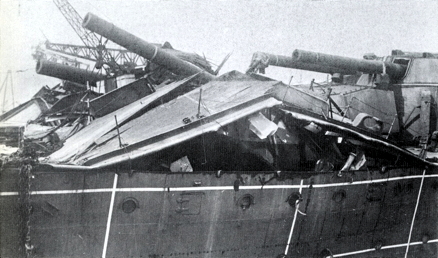

The Grand Fleet conducted another fruitless sweep of the North Sea in late December and, while trying to enter Scapa Flow in a Force 8

The Grand Fleet conducted another fruitless sweep of the North Sea in late December and, while trying to enter Scapa Flow in a Force 8 gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface winds moving at a speed of between 34 and 47 knots (, or ).rammed by ''Conqueror'' on 27 December. The former had to unexpectedly manoeuvre to avoid a  The Grand Fleet sortied in response to an attack by German ships on British light forces near Dogger Bank on 10 February 1916, but it was recalled two days later when it became clear that no German ships larger than a destroyer were involved. The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the

The Grand Fleet sortied in response to an attack by German ships on British light forces near Dogger Bank on 10 February 1916, but it was recalled two days later when it became clear that no German ships larger than a destroyer were involved. The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, departed the

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, departed the

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German  ''Monarch'' was

''Monarch'' was

Bird's eye view of the deck of H.M.S. ''Monarch''

(''Marine Engineer & Naval Architect'', December 1911)

Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project - HMS ''Monarch'' Crew List

{{DEFAULTSORT:Monarch (1911) Orion-class battleships Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Ships built on the River Tyne 1911 ships World War I battleships of the United Kingdom Ships sunk as targets Shipwrecks in the English Channel Maritime incidents in 1925

guardship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

at the entrance and ''Conqueror'' could not avoid her. ''Monarch'' suffered moderate damage to her stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

and received temporary repairs at Scapa before proceeding to Devonport for full repairs on 4 January 1915, rejoining the Grand Fleet on 20 January.

On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers, but ''Monarch'' and the rest of the fleet did not participate in the ensuing Battle of Dogger Bank the following day. On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet conducted a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March. On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

on 20–21 April.

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June, the fleet conducted gunnery practice and battle exercises west of Shetland and more training off Shetland beginning on 11 July. The 2nd BS conducted gunnery practice in the Moray Firth

The Moray Firth (; Scottish Gaelic: ''An Cuan Moireach'', ''Linne Mhoireibh'' or ''Caolas Mhoireibh'') is a roughly triangular inlet (or firth) of the North Sea, north and east of Inverness, which is in the Highland council area of north of Scotl ...

on 2 August and then returned to Scapa Flow. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises. The ship, together with the majority of the Grand Fleet, conducted another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Almost three weeks later, ''Monarch'' participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

during 2–5 November and repeated the exercise at the beginning of December.

The Grand Fleet sortied in response to an attack by German ships on British light forces near Dogger Bank on 10 February 1916, but it was recalled two days later when it became clear that no German ships larger than a destroyer were involved. The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the

The Grand Fleet sortied in response to an attack by German ships on British light forces near Dogger Bank on 10 February 1916, but it was recalled two days later when it became clear that no German ships larger than a destroyer were involved. The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, a p ...

to sweep the Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (german: Helgoländer Bucht) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends fro ...

, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea. Another sweep began on 6 March, but had to be abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the escorting destroyers. On the night of 25 March, ''Monarch'' and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface winds moving at a speed of between 34 and 47 knots (, or ).Horns Reef

Horns Rev is a shallow sandy reef of glacial deposits in the eastern North Sea, about off the westernmost point of Denmark, Blåvands Huk.

to distract the Germans while the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

relaid its defensive minefields

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft, but only arrived in the area after the Germans had withdrawn. On 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea.

Battle of Jutland

Jade Bight

The Jade Bight (or ''Jade Bay''; german: Jadebusen) is a bight or bay on the North Sea coast of Germany. It was formerly known simply as ''Jade'' or ''Jahde''. Because of the very low input of freshwater, it is classified as a bay rather than an ...

early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Hipper's five battlecruisers. Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.

On 31 May, ''Monarch'', under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

George Borrett

Admiral George Holmes Borrett, CB (10 March 1868 – 10 June 1952) was an officer of the Royal Navy. He served during the First World War, commanding a battleship at the Battle of Jutland, and later rising to the rank of admiral.

Early life ...

, was the sixth ship from the head of the battle line

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

after deployment. During the first stage of the general engagement, the ship fired three salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in one blow and prevent them from fighting b ...

s of armour-piercing, capped (APC) shells from her main guns at a group of five battleships at 18:32, scoring one hit on the dreadnought that knocked out a gun, temporarily disabled three boilers and started several small fires.The times used in this section are in UT, which is one hour behind CET

CET or cet may refer to:

Places

* Cet, Albania

* Cet, standard astronomical abbreviation for the constellation Cetus

* Colchester Town railway station (National Rail code CET), in Colchester, England

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Comcast En ...

, which is often used in German works. At 19:14, she engaged the battlecruiser at a range of with five salvos of APC shells and claimed to straddle

In finance, a straddle strategy involves two transactions in options on the same underlying, with opposite positions. One holds long risk, the other short. As a result, it involves the purchase or sale of particular option derivatives that allow ...

her with the last two salvos. ''Lützow'' was also fired at by ''Orion'' during this time and was hit five times between the sisters. They knocked out two of her main guns, temporarily knocked out the power to the sternmost turret and caused a fair amount of flooding. This was the last time that ''Monarch'' fired her guns during the battle, having expended a total of fifty-three 13.5-inch APC shells.

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or there was a strong possibility it could be forced into an engagement under suitable conditions.

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet again sortied, to attack British convoys to Norway. They enforced strict wireless silence during the operation, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser forced her to break radio silence to inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty then ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany. The ship was present at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

, Scotland, when the High Seas Fleet surrendered there on 21 November and she remained part of the 2nd BS through 1 March 1919.

By 1 May, ''Monarch'' had been assigned to the 3rd BS of the Home Fleet. On 1 November, the 3rd BS was disbanded and ''Monarch'' was transferred to the Reserve Fleet

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; a ...

at Portland, together with her sisters. The ship had been transferred back to Portsmouth by 18 March 1920. She was temporarily recommissioned during the summers of 1920 and 1921 to ferry troops to the Mediterranean and back. On 5 May 1922, ''Monarch'' was paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship in ...

and placed on the disposal list in accordance with the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

. Put up for sale in August, the ship was later withdrawn and attached to the gunnery school at as a hulk

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of ''The Incredible Hulk (comic book), The Incredible Hulk' ...

.

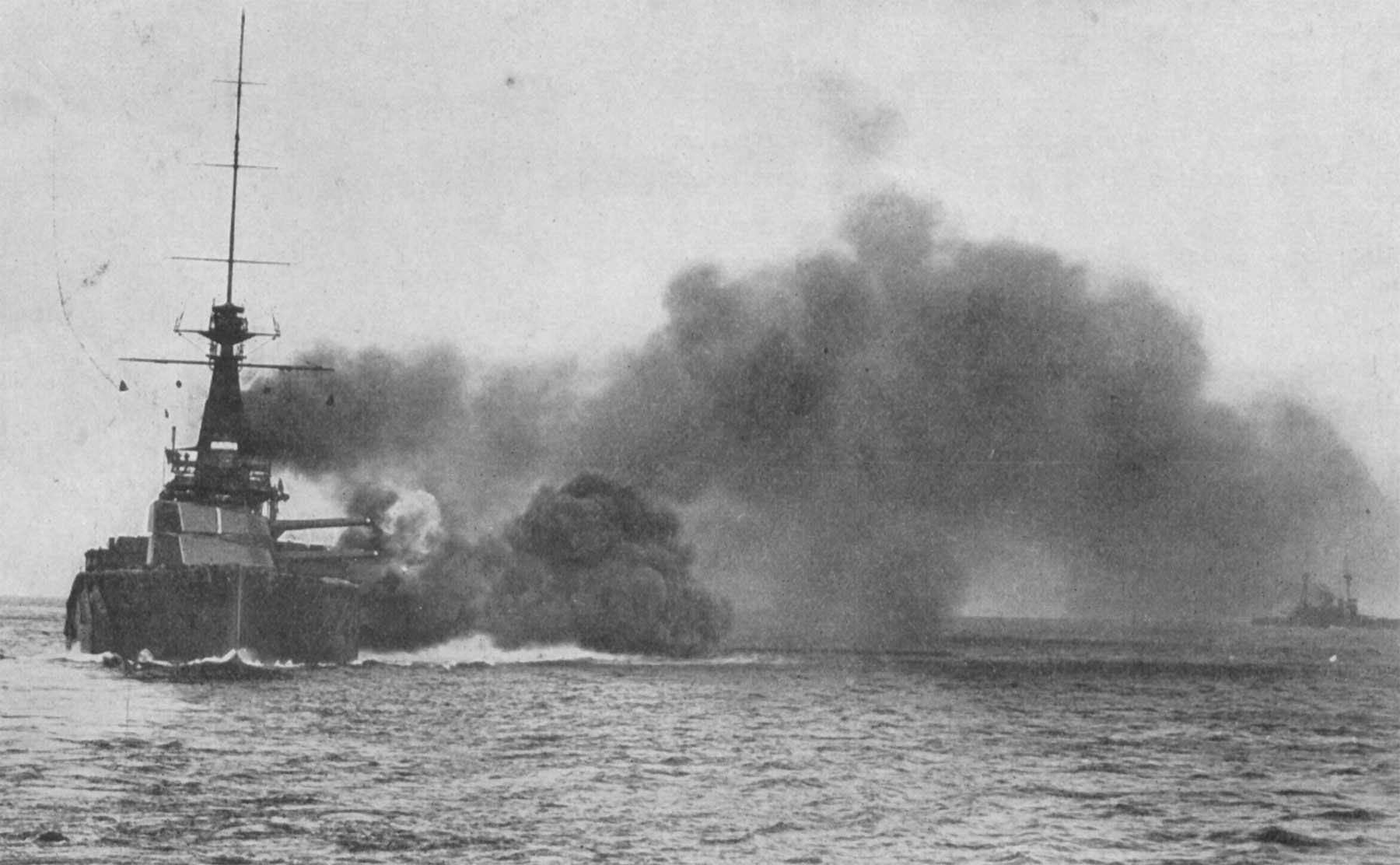

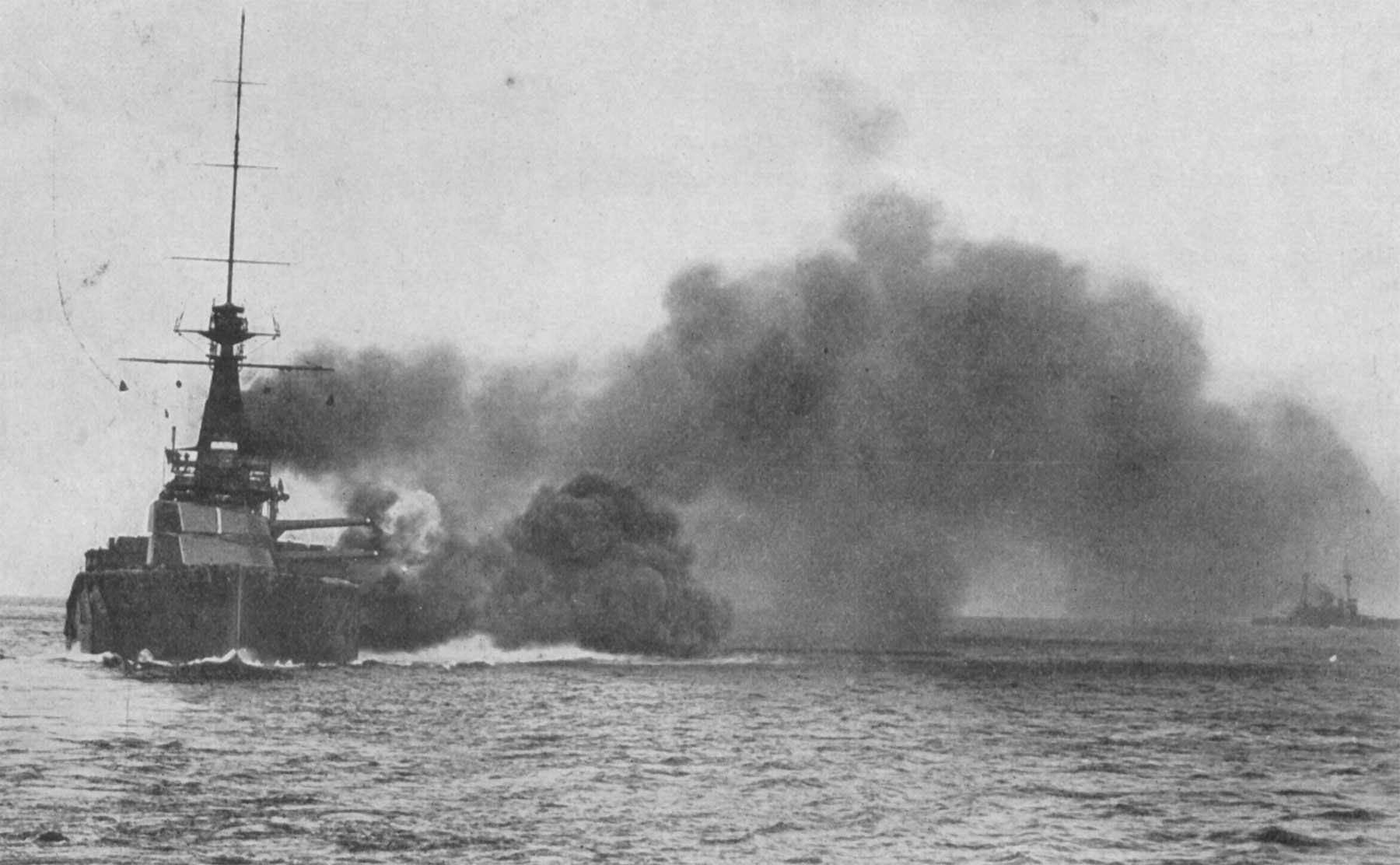

''Monarch'' was

''Monarch'' was paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship in ...

on 13 June 1923 and she was converted into a target ship at HM Dockyard, Portsmouth

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is l ...

in October 1923.Burt, p. 142 A replica of the underwater side protection of the s added to test the blast effects of large bombs detonating alongside the hull. A device consisting of of TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

(representing the explosives in a aerial bomb) was exploded at a depth of and from her side. Although damaged, the structure remained watertight after the test. The following year, live bombs of various sizes were dropped on the ship by Airco DH.9A

The Airco DH.9A was a British single-engined light bomber designed and first used shortly before the end of the First World War. It was a development of the unsuccessful Airco DH.9 bomber, featuring a strengthened structure and, crucially, repl ...

bombers with little effect. Bombs were then positioned and detonated internally to evaluate their effects. On 20 January 1925, ''Monarch'' was towed out from Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

by dockyard tugs into Hurd's Deep

Hurd's Deep (or Hurd Deep) is an underwater valley in the English Channel, northwest of the Channel Islands. Its maximum depth is about 180 m (590 ft; 98 fathoms), making it the deepest point in the English Channel.

Etymology

It is m ...

in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, approximately south of the Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain, being over further south than the most southerly point of the ...

. On 21 January she was attacked by a wave of Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

bombers, which scored several hits; this was followed by four light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s firing six-inch (152-mm) shells, and the destroyer , using her 4-inch guns. For the finale, the fast battleships and and the five s opened fire with their 15-inch (381-mm) guns. The number of hits on ''Monarch'' is unknown, but after nine hours of shelling she finally sank at 22:00. after a final hit by .

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Bird's eye view of the deck of H.M.S. ''Monarch''

(''Marine Engineer & Naval Architect'', December 1911)

Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project - HMS ''Monarch'' Crew List

{{DEFAULTSORT:Monarch (1911) Orion-class battleships Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Ships built on the River Tyne 1911 ships World War I battleships of the United Kingdom Ships sunk as targets Shipwrecks in the English Channel Maritime incidents in 1925