H. Newell Martin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

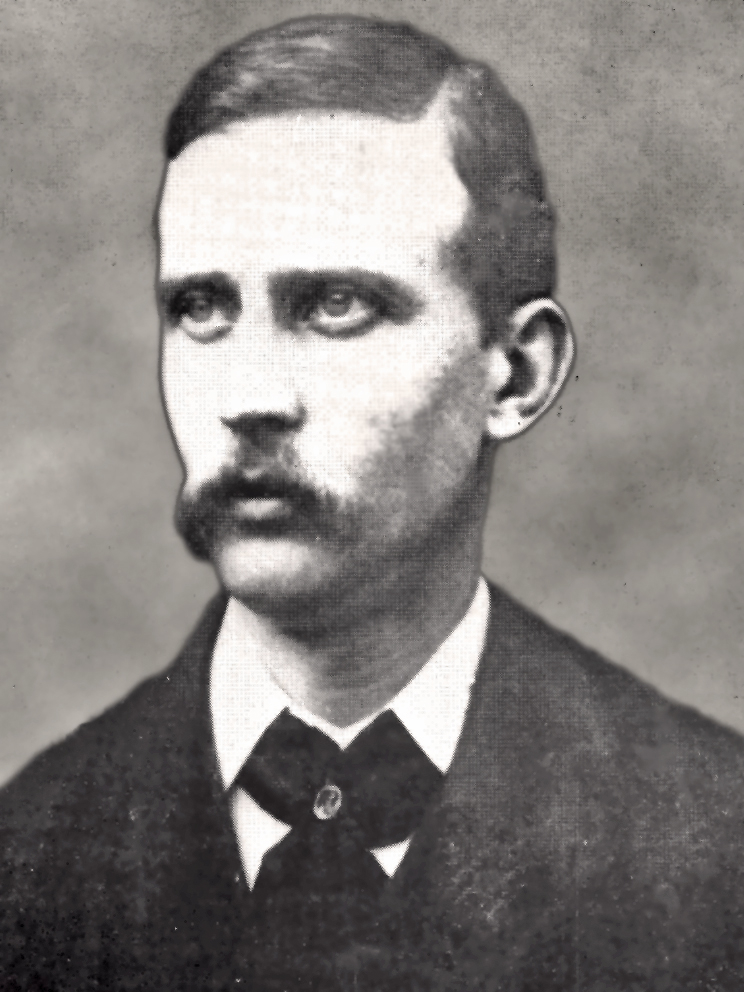

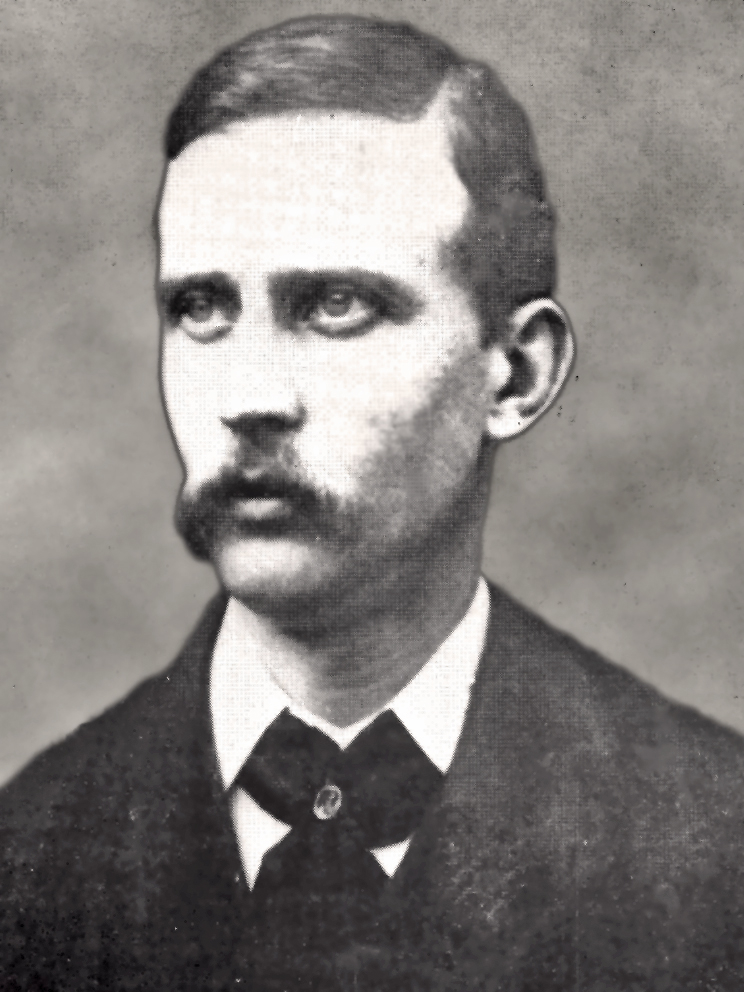

Henry Newell Martin, FRS (1 July 1848 – 27 October 1896) was a British

Henry Newell Martin, FRS (1 July 1848 – 27 October 1896) was a British

Introductory lecture, 23 October 1876. * * * * * * * * *

Various co-authors (including his wife for the 1st edition

10th edition online

*

Quoted by Fye. *

Collected articles.

H. Newell Martin bibliography

medicalarchives.jhmi.edu. Retrieved 6 May 2014. {{DEFAULTSORT:Martin, Henry Newell 1848 births 1896 deaths British physiologists Fellows of the Royal Society People from Newry Vivisection activists

Henry Newell Martin, FRS (1 July 1848 – 27 October 1896) was a British

Henry Newell Martin, FRS (1 July 1848 – 27 October 1896) was a British physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemica ...

and vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

activist.

Biography

He was born inNewry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Armagh, Armagh and County Down, Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to th ...

, the son of Henry Martin, a Congregational minister. He was educated at University College, London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = � ...

and Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

, where he matriculated in 1870, took the Part I Natural Sciences in 1873, and graduated B.A. in 1874. At the University of London, where he had graduated B.Sc. in 1870, he went on to become M.B. in 1871, and D.Sc. in 1872.

Martin worked as demonstrator to Michael Foster of Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

from 1870 to 1876; and was a Fellow of Christ's College for five years from 1874. Daniel Coit Gilman

Daniel Coit Gilman (; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic. Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College, and subsequently served as the second president of the University ...

of Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

, on advice from Foster and Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stori ...

, hired Martin in 1876 and set up the university's Biology Department around him.

Martin was appointed to the university's first professorship of physiology, one of the first five full professors appointed to the Hopkins faculty. It was understood that he would be laying the foundation for a medical school: Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM) is the medical school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1893, the School of Medicine shares a campus with the Johns Hopkins Hospi ...

eventually opened in 1893.

Having delivered the Croonian Lecture

The Croonian Medal and Lecture is a prestigious award, a medal, and lecture given at the invitation of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians.

Among the papers of William Croone at his death in 1684, was a plan to endow a single ...

in 1883 on ''"The Direct Influence of Gradual Variations of Temperature upon the Rate of Beat of the Dog's Heart"'', Martin was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

in 1885.

Martin's scientific career was curtailed around 1893, by alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

. He died on 27 October 1896 in Burley-in-Wharfedale

Burley in Wharfedale is a village and (as just Burley) a civil parish in the City of Bradford in West Yorkshire, England. It is situated in the Wharfedale valley.

The village is situated on the A65 road, approximately north-west from Leed ...

, Yorkshire.

Work

Martin developed the first isolated mammalian heart lung preparation (described in 1881), whichErnest Henry Starling

Ernest Henry Starling (17 April 1866 – 2 May 1927) was a British physiologist who contributed many fundamental ideas to this subject. These ideas were important parts of the British contribution to physiology, which at that time led the world. ...

later used. He collaborated with George Nuttall

George Henry Falkiner Nuttall FRS (5 July 1862 – 16 December 1937) was an American-British bacteriologist who contributed much to the knowledge of parasites and of insect carriers of diseases. He made significant innovative discoveries in immu ...

, at Baltimore for a year around 1885. With the hiring of William Keith Brooks

William Keith Brooks (March 25, 1848 – November 12, 1908) was an American zoologist, born in Cleveland, Ohio, March 25, 1848. Brooks studied embryological development in invertebrates and founded a marine biological laboratory where he and oth ...

came the opening of the Chesapeake Zoological Laboratory. It conducted its work at stations from Beaufort, North Carolina

Beaufort ( ) is a town in and the county seat of Carteret County, North Carolina, United States. Established in 1713 and incorporated in 1723, Beaufort is the fourth oldest town in North Carolina (after Bath, New Bern and Edenton).

On February ...

, to the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

, studying marine life and interdependencies between species.

Views

Martin represented and spread the views of the Cambridge school of physiology around Michael Foster, which took account in a basic way of thetheory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

. He co-wrote ''A Course of Practical Instruction in Elementary Biology'' (1875) with Thomas Huxley, a leading proponent of evolution. It was based on Huxley's annual summer course, given since 1871, of laboratory teaching for future science teachers; and concentrated on a small number of types of plants and animals.

Biology labs were under attack by those opposed to experiments on live animals, a procedure known as vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

. Martin defended vivisection, stating "Physiology is concerned with the phenomena going on in living things, and vital processes cannot be observed in dead bodies." He invited visitors to his lab to observe experiments.Hugh Hawkins, ''Pioneer: A History of the Johns Hopkins University, 1874-1889'' (Ithaca, NY, 1960)

Selected publications

* * *Introductory lecture, 23 October 1876. * * * * * * * * *

Various co-authors (including his wife for the 1st edition

10th edition online

*

Quoted by Fye. *

Collected articles.

Personal life

In 1879, Martin marriedHetty Cary

Hetty Carr Cary (May 15, 1836 – September 27, 1892) was the wife of Confederate General John Pegram and, later, of pioneer physiologist H. Newell Martin. She is best remembered for making the first three battle flags of the Confederacy (al ...

, widow of Confederate General John Pegram

John Pegram (November 16, 1773April 8, 1831) was a Virginia planter, soldier and politician who served in the United States House of Representatives, both houses of the Virginia General Assembly and a major general during the War of 1812.

Ear ...

.

References

External links

*H. Newell Martin bibliography

medicalarchives.jhmi.edu. Retrieved 6 May 2014. {{DEFAULTSORT:Martin, Henry Newell 1848 births 1896 deaths British physiologists Fellows of the Royal Society People from Newry Vivisection activists