H. L. Mencken on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist,

In 1930, Mencken married

In 1930, Mencken married

During the

During the

The Sahara of the Bozart

'' (1920) * '' Gamalielese'' (1921) *

The Hills of Zion

(1925) * '' The Libido for the Ugly'' (1927) * The Penalty of Death

H. L. Mencken Collection

– Enoch Pratt Free Library (Digital Maryland)

Baltimore of Sara Haardt and H.L. Mencken, 1923–1935

– Goucher College (Digital Maryland)

at positiveatheism.org

The Papers of the Wilton C. Dinges Collection (H. L. Mencken Collection)

at

H. L. and Sara Haardt Mencken Collection

at

H. L. Mencken Papers

at

FBI file on H. L. Mencken

at

Recorded interview of H. L. Mencken in 1948

"Writings of H.L. Mencken"

from

H. L. Mencken, Le Contrat Social

(1922)

at the Archive of American Journalism *

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

H.L. Mencken correspondence, 1926–1937

Guide to the H. L. Mencken Collection 1925–1933

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

Arthur J. Gutman Collection of Menckeniana

at the

essayist

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal a ...

, satirist

This is an incomplete list of writers, cartoonists and others known for involvement in satire – humorous social criticism. They are grouped by era and listed by year of birth. Included is a list of modern satires.

Under Contemporary, 1930-1960 ...

, cultural critic

A cultural critic is a critic of a given culture, usually as a whole. Cultural criticism has significant overlap with social and cultural theory. While such criticism is simply part of the self-consciousness of the culture, the social positions of ...

, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, and contemporary movements. His satirical reporting on the Scopes Trial, which he dubbed the "Monkey Trial", also gained him attention.

As a scholar, Mencken is known for ''The American Language

''The American Language; An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States'', first published in 1919, is H. L. Mencken's book about the English language as spoken in the United States.

Origins and concept

Mencken was inspired by ...

'', a multi-volume study of how the English language is spoken in the United States. As an admirer of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, he was an outspoken opponent of organized religion

Organized religion, also known as institutional religion, is religion in which belief systems and rituals are systematically arranged and formally established. Organized religion is typically characterized by an official doctrine (or dogma), a ...

, theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

, and representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represen ...

, the last of which he viewed as a system in which inferior men dominated their superiors. Mencken was a supporter of scientific progress and was critical of osteopathy

Osteopathy () is a type of alternative medicine that emphasizes physical manipulation of the body's muscle tissue and bones. Practitioners of osteopathy are referred to as osteopaths.

Osteopathic manipulation is the core set of techniques in ...

and chiropractic

Chiropractic is a form of alternative medicine concerned with the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of mechanical disorders of the musculoskeletal system, especially of the spine. It has esoteric origins and is based on several pseudosci ...

. He was also an open critic of economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and intera ...

.

Mencken opposed the American entry into World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Some of the opinions in his private diary entries have been described by some researchers as racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

and anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, although this characterization has been disputed. Larry S. Gibson

Larry S. Gibson (born March 22, 1942) is a law professor, lawyer, political organizer, and historian. He currently serves as a professor at the Francis King Carey School of Law in the University of Maryland, Baltimore; where he has been on the f ...

argued that Mencken's views on race changed significantly between his early and later writings, and that it was more accurate to describe Mencken as elitist rather than racist. He seemed to show a genuine enthusiasm for militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

but never in its American form. "War is a good thing", he wrote, "because it is honest, it admits the central fact of human nature.... A nation too long at peace becomes a sort of gigantic old maid".

His longtime home in the Union Square

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

neighborhood of West Baltimore

West Baltimore station is a regional rail station located in the western part of the City of Baltimore, Maryland along the Northeast Corridor. It is served by MARC Penn Line trains. The station is positioned on an elevated grade above and betwe ...

was turned into a city museum, the H. L. Mencken House

The H. L. Mencken House was the home of ''Baltimore Sun'' journalist and author Henry Louis Mencken, who lived here from 1883 until his death in 1956. The Italianate brick row house at 1524 Hollins Street in Baltimore was designated a National ...

. His papers were distributed among various city and university libraries, with the largest collection held in the Mencken Room at the central branch of Baltimore's Enoch Pratt Free Library

The Enoch Pratt Free Library is the free public library system of Baltimore, Maryland. Its Central Library and office headquarters are located on 400 Cathedral Street (southbound) and occupy the northeastern three quarters of a city block bound ...

.

Early life

Mencken was born inBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, on September 12, 1880. He was the son of Anna Margaret (Abhau) and August Mencken Sr., a cigar factory owner. He was of German ancestry and spoke German in his childhood. When Henry was three, his family moved into a new home at 1524 Hollins Street facing Union Square park in the Union Square

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

neighborhood of old West Baltimore. Apart from five years of married life, Mencken was to live in that house for the rest of his life.

In his bestselling memoir ''Happy Days

''Happy Days'' is an American television sitcom that aired first-run on the ABC network from January 15, 1974, to July 19, 1984, with a total of 255 half-hour episodes spanning 11 seasons. Created by Garry Marshall, it was one of the most succ ...

'', he described his childhood in Baltimore as "placid, secure, uneventful and happy".

When he was nine years old, he read Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

's ''Huckleberry Finn

Huckleberry "Huck" Finn is a fictional character created by Mark Twain who first appeared in the book ''The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'' (1876) and is the protagonist and narrator of its sequel, ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' (1884). He is 12 ...

'', which he later described as "the most stupendous event in my life". He became determined to become a writer and read voraciously. In one winter while in high school he read William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

and then "proceeded backward to Addison

Addison may refer to:

Places Canada

* Addison, Ontario

United States

*Addison, Alabama

*Addison, Illinois

*Addison Street in Chicago, Illinois which runs by Wrigley Field

* Addison, Kentucky

*Addison, Maine

*Addison, Michigan

*Addison, New York

...

, Steele

Steele may refer to:

Places America

* Steele, Alabama, a town

* Steele, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Steele, Kentucky, an unincorporated community

* Steele, Missouri, a city

* Lonetree, Montana, a ghost town originally called Steele ...

, Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, Swift

Swift or SWIFT most commonly refers to:

* SWIFT, an international organization facilitating transactions between banks

** SWIFT code

* Swift (programming language)

* Swift (bird), a family of birds

It may also refer to:

Organizations

* SWIFT, ...

, Johnson

Johnson is a surname of Anglo-Norman origin meaning "Son of John". It is the second most common in the United States and 154th most common in the world. As a common family name in Scotland, Johnson is occasionally a variation of ''Johnston'', a ...

and the other magnificos of the Eighteenth century". He read the entire canon of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and became an ardent fan of Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

and Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

. As a boy, Mencken also had practical interests, photography and chemistry in particular, and eventually had a home chemistry laboratory in which he performed experiments of his own design,

some of them inadvertently dangerous.

He began his primary education in the mid-1880s at Professor Knapp's School on the east side of Holliday Street between East Lexington and Fayette Streets, next to the Holliday Street Theatre

The Holliday Street Theater also known as the New Theatre, New Holliday, Old Holliday, The Baltimore Theatre, and Old Drury, was a historical theatrical venue in Federal Period Baltimore, Maryland. It is known for showing the first performance of F ...

and across from the newly constructed Baltimore City Hall

Baltimore City Hall is the official seat of government of the City of Baltimore, in the State of Maryland. The City Hall houses the offices of the Mayor and those of the City Council of Baltimore. The building also hosts the city Comptroller, som ...

. The site today is the War Memorial and City Hall Plaza laid out in 1926 in memory of World War I dead. At 15, in June 1896, he graduated as valedictorian from the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute

The Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, colloquially referred to as BPI, Poly, and The Institute, is a U.S. public high school founded in 1883. Established as an all-male manual trade / vocational school by the Baltimore City Council and the Baltim ...

, at the time a males-only mathematics, technical and science-oriented public high school.

He worked for three years in his father's cigar factory. He disliked the work, especially the sales aspect of it, and resolved to leave, with or without his father's blessing. In early 1898 he took a writing class at the Cosmopolitan University, a free correspondence school. This was to be the entirety of Mencken's formal post-secondary education in journalism, or in any other subject. Upon his father's death a few days after Christmas in the same year, the business passed to his uncle, and Mencken was free to pursue his career in journalism. He applied in February 1899 to the ''Morning Herald'' newspaper (which became the ''Baltimore Morning Herald

''The Baltimore Morning Herald'' was a daily newspaper published in Baltimore in the beginning of the twentieth century.

History

The first edition was published on February 10, 1900. The paper succeeded the ''Morning Herald'' and was absorbed b ...

'' in 1900) and was hired part-time, but still kept his position at the factory for a few months. In June he was hired as a full-time reporter.

Career

Mencken served as a reporter at the ''Herald'' for six years. Less than two-and-a-half years after theGreat Baltimore Fire

The Great Baltimore Fire raged in Baltimore, Maryland from Sunday, February 7, to Monday, February 8, 1904. More than 1,500 buildings were completely leveled, and some 1,000 severely damaged, bringing property loss from the disaster to an estimate ...

, the paper was purchased in June 1906 by Charles H. Grasty

Charles Henry Grasty (March 3, 1863—January 19, 1924) was a well-known American newspaper operator who at one time controlled '' The News'' an afternoon paper begun in 1871 and later '' The Sun'' of Baltimore, a morning major daily newspap ...

, the owner and editor of '' The News'' since 1892, and competing owner and publisher Gen. Felix Agnus

Felix Agnus (4 July 1839 – 31 October 1925) was a French-born sculptor, newspaper publisher and soldier who served in the Franco-Austrian War and the American Civil War. Agnus studied sculpture before enlisting to fight in the Franco-Austrian ...

, of the town's oldest (since 1773) and largest daily, '' The Baltimore American.'' They proceeded to divide the staff, assets and resources of ''The Herald'' between them. Mencken then moved to ''The Baltimore Sun

''The Baltimore Sun'' is the largest general-circulation daily newspaper based in the U.S. state of Maryland and provides coverage of local and regional news, events, issues, people, and industries.

Founded in 1837, it is currently owned by Tr ...

'', where he worked for Charles H. Grasty. He continued to contribute to ''The Sun,'' ''The Evening Sun'' (founded 1910) and ''The Sunday Sun'' full-time until 1948, when he stopped writing after suffering a stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

.

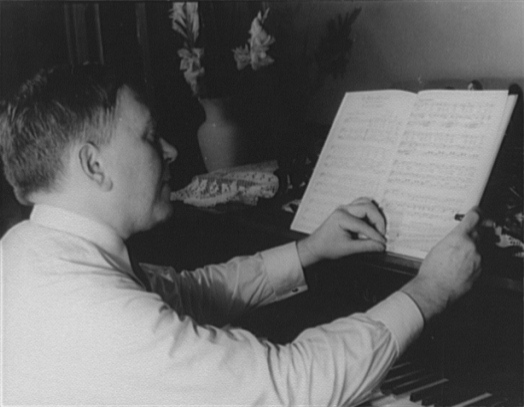

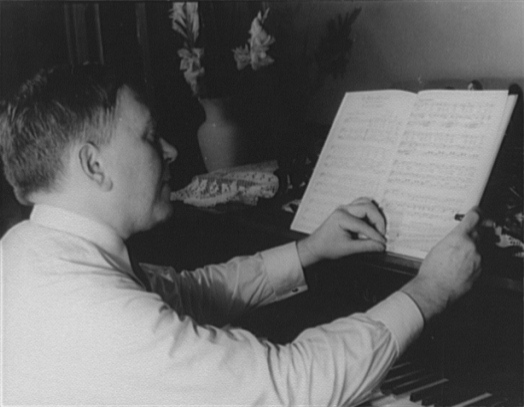

Mencken began writing the editorials and opinion pieces that made his name at ''The Sun.'' On the side, he wrote short stories, a novel, and even poetry, which he later revealed. In 1908, he became a literary critic for ''The Smart Set

''The Smart Set'' was an American literary magazine, founded by Colonel William d'Alton Mann and published from March 1900 to June 1930. Its headquarters was in New York City. During its Jazz Age heyday under the editorship of H. L. Mencken and G ...

'' magazine, and in 1924 he and George Jean Nathan

George Jean Nathan (February 14, 1882 – April 8, 1958) was an American drama critic and magazine editor. He worked closely with H. L. Mencken, bringing the literary magazine ''The Smart Set'' to prominence as an editor, and co-founding and ...

founded and edited ''The American Mercury

''The American Mercury'' was an American magazine published from 1924Staff (Dec. 31, 1923)"Bichloride of Mercury."''Time''. to 1981. It was founded as the brainchild of H. L. Mencken and drama critic George Jean Nathan. The magazine featured wri ...

'', published by Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Alfred A. Knopf Sr. and Blanche Knopf in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers in ...

. It soon developed a national circulation and became highly influential on college campuses across America. In 1933, Mencken resigned as editor.

Personal life

Marriage

In 1930, Mencken married

In 1930, Mencken married Sara Haardt

Sara Powell Haardt (March 1, 1898 – May 31, 1935) was an American author and professor of English literature. Though she died at the age of 37 of meningitis, she produced a considerable body of work including newspaper reviews, articles, essay ...

, a German-American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

professor of English at Goucher College

Goucher College ( ') is a private liberal arts college in Towson, Maryland. It was chartered in 1885 by a conference in Baltimore led by namesake John F. Goucher and local leaders of the Methodist Episcopal Church.https://archive.org/details/h ...

in Baltimore and an author eighteen years his junior. Haardt had led an unsuccessful effort in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

to ratify the 19th Amendment. The two met in 1923, after Mencken delivered a lecture at Goucher; a seven-year courtship ensued. The marriage made national headlines, and many were surprised that Mencken, who once called marriage "the end of hope" and who was well known for mocking relations between the sexes, had gone to the altar. "The Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

informed and inspired me", Mencken said. "Like all other infidels, I am superstitious and always follow hunches: this one seemed to be a superb one." Even more startling, he was marrying an Alabama native, despite his having written scathing essays about the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Haardt was in poor health from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

throughout their marriage and died in 1935 of meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

, leaving Mencken grief-stricken. He had always championed her writing and, after her death, had a collection of her short stories published under the title ''Southern Album''.

Great Depression, war, and afterward

During the

During the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, Mencken did not support the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

, which cost him popularity, as did his strong reservations regarding U.S. participation in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and his overt contempt for President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. He ceased writing for ''The Baltimore Sun'' for several years, focusing on his memoirs and other projects as editor while he served as an adviser for the paper that had been his home for nearly his entire career. In 1948, he briefly returned to the political scene to cover the presidential election in which President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

faced Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Thomas Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

and Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. S ...

of the Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Italy

...

. His later work consisted of humorous, anecdotal, and nostalgic essays that were first published in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' and then collected in the books ''Happy Days'', ''Newspaper Days'', and ''Heathen Days''.

Last years

On November 23, 1948, Mencken suffered astroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

, which left him aware and fully conscious but nearly unable to read or write and able to speak only with difficulty. After his stroke, Mencken enjoyed listening to classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

and, after some recovery of his ability to speak, talking with friends, but he sometimes referred to himself in the past tense, as if he were already dead. During the last year of his life, his friend and biographer William Manchester

William Raymond Manchester (April 1, 1922 – June 1, 2004) was an American author, biographer, and historian. He was the author of 18 books which have been translated into over 20 languages. He was awarded the National Humanities Medal and the ...

read to him daily.

Death

Mencken died in his sleep on January 29, 1956. He was interred in Baltimore'sLoudon Park Cemetery

Loudon Park Cemetery is a historic cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland. It was incorporated on January 27, 1853, on of the site of the "Loudon" estate, previously owned by James Carey, a local merchant and politician. The entrance to the cemetery i ...

.

Though it does not appear on his tombstone, Mencken, during his ''Smart Set'' days, wrote a joking epitaph for himself:

A very small, short, and private service was held, in accordance with Mencken's wishes.

Mencken was preoccupied with his legacy and kept his papers, letters, newspaper clippings, columns, and even grade school report cards. After his death, those materials were made available to scholars in stages in 1971, 1981, and 1991 and include hundreds of thousands of letters sent and received. The only omissions were strictly personal letters received from women.

Beliefs

In his capacity as editor, Mencken became close friends with the leading literary figures of his time, includingTheodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm mora ...

, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Joseph Hergesheimer

Joseph Hergesheimer (February 15, 1880 – April 25, 1954) was an American writer of the early 20th century known for his naturalistic novels of decadent life amongst the very wealthy.

Early life

Hergesheimer was born on February 15, 1880 Phil ...

, Anita Loos

Corinne Anita Loos (April 26, 1888 – August 18, 1981) was an American actress, novelist, playwright and screenwriter. In 1912, she became the first female staff screenwriter in Hollywood, when D. W. Griffith put her on the payroll at Triang ...

, Ben Hecht

Ben Hecht (; February 28, 1894 – April 18, 1964) was an American screenwriter, director, producer, playwright, journalist, and novelist. A successful journalist in his youth, he went on to write 35 books and some of the most enjoyed screenplay ...

, Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

, James Branch Cabell

James Branch Cabell (; April 14, 1879 – May 5, 1958) was an American author of fantasy fiction and ''belles-lettres''. Cabell was well-regarded by his contemporaries, including H. L. Mencken, Edmund Wilson, and Sinclair Lewis. His works ...

, and Alfred Knopf, as well as a mentor to several young reporters, including Alistair Cooke

Alistair Cooke (born Alfred Cooke; 20 November 1908 – 30 March 2004) was a British-American writer whose work as a journalist, television personality and radio broadcaster was done primarily in the United States.Eddie Cantor

Eddie Cantor (born Isidore Itzkowitz; January 31, 1892 – October 10, 1964) was an American comedian, actor, dancer, singer, songwriter, film producer, screenwriter and author. Familiar to Broadway, radio, movie, and early television audiences, ...

(ghostwritten by David Freedman

David Freedman (April 26, 1898 – December 8, 1936) (aged 38) was a Romanian-born American playwright and biographer who became known as the "King of the Gag-writers" in the early days of radio.

Biography

David Freedman was born in Botoşan ...

) did more to pull America out of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

than all government measures combined. He also mentored John Fante

John Fante (April 8, 1909 – May 8, 1983) was an American novelist, short story writer, and screenwriter. He is best known for his semi-autobiographical novel ''Ask the Dust'' (1939) about the life of Arturo Bandini, a struggling writer in Depre ...

. Thomas Hart Benton illustrated an edition of Mencken's book ''Europe After 8:15''.

Mencken also published many works under various pseudonyms, including Owen Hatteras Major Owen Hatteras (1912–1923) is a composite personage and pseudonym created and employed by H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan for ''The Smart Set'' literary magazine and adapted by Willard Huntington Wright during his short tenure as edi ...

, John H Brownell, William Drayham, WLD Bell, and Charles Angoff

Charles Angoff (April 22, 1902 – May 3, 1979) was a managing editor of the American Mercury magazine as well as a professor of English of Fairleigh Dickinson University. H. L. Mencken called him "the best managing editor in America." He wa ...

. As a ghostwriter for the physician Leonard K. Hirshberg, he wrote a series of articles and, in 1910, most of a book about the care of babies.

Mencken admired the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

(he was the first writer to provide a scholarly analysis in English of Nietzsche's views and writings) and Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

. His humor and satire owed much to Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book ''The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by t ...

and Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

. He did much to defend Dreiser despite freely admitting his faults, including stating forthrightly that Dreiser often wrote badly and was gullible. Mencken expressed his appreciation for William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and classical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University—where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology—and be ...

in a 1941 collection of Sumner's essays and regretted never having known Sumner personally. In contrast, Mencken was scathing in his criticism of the German philosopher Hans Vaihinger

Hans Vaihinger (; September 25, 1852 – December 18, 1933) was a German philosopher, best known as a Kant scholar and for his ''Die Philosophie des Als Ob'' ('' The Philosophy of 'As if), published in 1911 although its statement of basic ...

, whom Mencken described as "an extremely dull author" and whose famous book ''Philosophy of 'As If he dismissed as an unimportant "foot-note to all existing systems".

Mencken recommended for publication philosopher and author Ayn Rand

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum;, . Most sources transliterate her given name as either ''Alisa'' or ''Alissa''. , 1905 – March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and p ...

's first novel, ''We the Living

''We the Living'' is the debut novel of the Russian American novelist Ayn Rand. It is a story of life in post-revolutionary Russia and was Rand's first statement against communism. Rand observes in the foreword that ''We the Living'' was the cl ...

'' and called it "a really excellent piece of work". Shortly afterward, Rand addressed him in correspondence as "the greatest representative of a philosophy" to which she wanted to dedicate her life, "individualism" and later listed him as her favorite columnist.

For Mencken, ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' or as it is known in more recent editions, ''The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'', is a novel by American author Mark Twain, which was first published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the United St ...

'' was the finest work of American literature

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and in the colonies that preceded it. The American literary tradition thus is part of the broader tradition of English-language literature, but also inc ...

. He particularly relished Mark Twain's depiction of a succession of gullible and ignorant townspeople, "boobs", as Mencken referred to them, who are repeatedly gulled by a pair of colorful con men

A confidence trick is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using their credulity, naïveté, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibility, and greed. Researchers have def ...

: the deliberately pathetic "Duke" and "Dauphin", with whom Huck and Jim

Jim or JIM may refer to:

* Jim (given name), a given name

* Jim, a diminutive form of the given name James

* Jim, a short form of the given name Jimmy

* OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism

* ''Jim'' (comics), a series by Jim Woodring

* ''Jim ...

travel down the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. For Mencken, the depiction epitomizes the hilarious dark side of America, where democracy, as defined by Mencken, is "the worship of jackals by jackasses".

Such turns of phrase evoked the erudite cynicism and rapier sharpness of language displayed by Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book ''The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by t ...

in his darkly-satiric ''The Devil's Dictionary

''The Devil's Dictionary'' is a satire, satirical dictionary written by American journalist Ambrose Bierce, consisting of common words followed by humorous and satirical definitions. The lexicon was written over three decades as a series of insta ...

''. A noted curmudgeon, democratic in subjects attacked, Mencken savaged politics, hypocrisy, and social convention. A master of English, he was given to bombast and once disdained the lowly hot dog bun's descent into "the soggy rolls prevailing today, of ground acorns, plaster of Paris, flecks of bath sponge and atmospheric air all compact".

Defining Puritanism

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

as "the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy", Mencken believed that the U.S. had not cast aside the Puritans' influence. He opined that American culture, unlike its European counterparts, had not attained intellectual freedom, and judged literature by moral orthodoxy and not by artistic merit. His most outspoken essay was "Puritanism as a Literary Force" from his 1917 collection of essays '' A Book of Prefaces'':

As a nationally-syndicated columnist

A columnist is a person who writes for publication in a series, creating an article that usually offers commentary and opinions. Column (newspaper), Columns appear in newspapers, magazines and other publications, including blogs. They take the fo ...

and book author, he commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians and contemporary movements, such as the temperance movement. Mencken was a keen cheerleader of scientific progress but was skeptical of economic theories and strongly opposed to osteopathic

Osteopathy () is a type of alternative medicine that emphasizes physical manipulation of the body's muscle tissue and bones. Practitioners of osteopathy are referred to as osteopaths.

Osteopathic manipulation is the core set of techniques in ...

/chiropractic

Chiropractic is a form of alternative medicine concerned with the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of mechanical disorders of the musculoskeletal system, especially of the spine. It has esoteric origins and is based on several pseudosci ...

medicine. He also debunked the idea of objective news reporting since "truth is a commodity that the masses of undifferentiated men cannot be induced to buy" and added a humorous description of how "Homo Boobus", like "higher mammalia", is moved by "whatever gratifies his prevailing yearnings".

As a frank admirer of Nietzsche, Mencken was a detractor of representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represen ...

, which he believed was a system in which inferior men dominated their superiors. Like Nietzsche, he also lambasted religious belief

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people often ...

and the very concept of God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

, as Mencken was an unflinching atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

, particularly Christian fundamentalism

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British and ...

, Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally know ...

and creationism

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 't ...

, and against the "Booboisie", his word for the ignorant middle classes. In the summer of 1925, he attended the famous Scopes "Monkey Trial" in Dayton, Tennessee, and wrote scathing columns for the ''Baltimore Sun'' (widely syndicated) and ''American Mercury'' mocking the anti-evolution

Objections to evolution have been raised since evolutionary ideas came to prominence in the 19th century. When Charles Darwin published his 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species'', his theory of evolution (the idea that species arose through desc ...

fundamentalists (especially William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

). The play '' Inherit the Wind'' is a fictionalized version of the trial, and as noted above the cynical reporter E.K. Hornbeck is based on Mencken. In 1926, he deliberately had himself arrested for selling an issue of ''The American Mercury'', which was banned in Boston

"Banned in Boston" is a phrase that was employed from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, to describe a literary work, song, motion picture, or play which had been prohibited from distribution or exhibition in Boston, Massachuset ...

by the Comstock laws

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression of ...

. Mencken heaped scorn not only on the public officials he disliked but also on the state of American elective politics itself.

In the summer of 1926, Mencken followed with great interest the Los Angeles grand jury inquiry into the famous Canadian-American evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson

Aimee Elizabeth Semple McPherson (née Kennedy; October 9, 1890 – September 27, 1944), also known as Sister Aimee or Sister, was a Canadian Pentecostalism, Pentecostal Evangelism, evangelist and media celebrity in the 1920s and 1930s,Ob ...

. She was accused of faking her reported kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

and the case attracted national attention. There was every expectation that Mencken would continue his previous pattern of anti-fundamentalist articles, this time with a searing critique of McPherson. Unexpectedly, he came to her defense by identifying various local religious and civic groups that were using the case as an opportunity to pursue their respective ideological agendas against the embattled Pentecostal

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement

minister. He spent several weeks in Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, and wrote many scathing and satirical columns on the movie industry and Southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most po ...

culture. After all charges had been dropped against McPherson, Mencken revisited the case in 1930 with a sarcastic and observant article. He wrote that since many of that town's residents had acquired their ideas "of the true, the good and the beautiful" from the movies and newspapers, "Los Angeles will remember the testimony against her long after it forgets the testimony that cleared her".

In 1931, the Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

legislature passed a motion to pray for Mencken's soul after he had called the state the "apex of moronia".

In the mid-1930s, Mencken feared Roosevelt and his New Deal liberalism

Modern liberalism in the United States, often simply referred to in the United States as liberalism, is a form of social liberalism found in American politics. It combines ideas of civil liberty and equality with support for social justice and ...

as a powerful force. Mencken, says Charles A. Fecher, was "deeply conservative, resentful of change, looking back upon the 'happy days' of a bygone time, wanted no part of the world that the New Deal promised to bring in".

Views

Race and elitism

In addition to his identification of races with castes, Mencken had views about the superior individual within communities. He believed that every community produced a few people of clear superiority. He considered groupings on a par with hierarchies, which led to a kind of naturalelitism

Elitism is the belief or notion that individuals who form an elite—a select group of people perceived as having an intrinsic quality, high intellect, wealth, power, notability, special skills, or experience—are more likely to be constructi ...

and natural aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At t ...

. "Superior" individuals, in Mencken's view, were those wrongly oppressed and disdained by their own communities but nevertheless distinguished by their will and personal achievement, not by race or birth.

In 1989, per his instructions, Alfred A. Knopf published Mencken's "secret diary" as ''The Diary of H. L. Mencken''. According to an Associated Press story, Mencken's views shocked even the "sympathetic scholar who edited it", Charles A. Fecher of Baltimore. A club in Baltimore, the Maryland Club

Founded in 1857, the Maryland Club is one of the oldest private clubs in the United States that was founded as an exclusive men's club. Its large Romanesque clubhouse, dating to 1891, is located in Baltimore’s historic Mount Vernon neighborho ...

, had one Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

member. When that member died, Mencken said, "There is no other Jew in Baltimore who seems suitable." The diary also quoted him as saying of blacks, in September 1943, that "it is impossible to talk anything resembling discretion or judgment to a colored woman. They are all essentially child-like, and even hard experience does not teach them anything".

Mencken opposed lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

. In 1935, he testified before Congress in support of the Costigan–Wagner Bill. While he had previously written negatively about lynchings during the 1910s and 1920s, the lynchings of Matthew Williams and George Armwood

George Armwood was lynched in Princess Anne, Maryland, on October 18, 1933. His murder was the last recorded lynching in Maryland.

Details of the crime

On October 16, 1933, a 71-year-old woman named Mary Denston was assaulted walking home from the ...

caused him to write in support of the bill give political advice to Walter Francis White

Walter Francis White (July 1, 1893 – March 21, 1955) was an American civil rights activist who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for a quarter of a century, 1929–1955, after joining the organi ...

on how to maximize the liklihood of the bill's passing. The two lynchings in his home state made the issue directly relevant to him. His arguments against lynching were influenced by his interpretation of civilization, as he believed that a civilized society would not tolerate it.

Mencken also wrote:

In a review of ''The Skeptic: A Life of H. L. Mencken'', by Terry Teachout

Terrance Alan Teachout (February 6, 1956 – January 13, 2022) was an American author, critic, biographer, playwright, stage director, and librettist.

He was the drama critic of ''The Wall Street Journal'', the critic-at-large of ''Commentary'' ...

, journalist Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British-American author and journalist who wrote or edited over 30 books (including five essay collections) on culture, politics, and literature. Born and educated in England, ...

described Mencken as a German nationalist

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of Germans and German-speakers into one unified nation state. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism and national identity of Germans as one nat ...

, "an antihumanist as much as an atheist", who was "prone to the hyperbole and sensationalism he distrusted in others". Hitchens also criticized Mencken for writing a scathing critique of Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

but nothing equally negative of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

.

Larry S. Gibson

Larry S. Gibson (born March 22, 1942) is a law professor, lawyer, political organizer, and historian. He currently serves as a professor at the Francis King Carey School of Law in the University of Maryland, Baltimore; where he has been on the f ...

argued that Mencken's views on race changed significantly between his early and later writings, attributing some of the changes in Mencken's views to his personal experiences of being treated as an outsider due to his German heritage during World War I. Gibson speculated that much of Mencken's language was intended to lure in readers by suggesting a shared negative view of other races, and then writing about their positive aspects. Describing Mencken as elitist rather than racist, he says Mencken ultimately believed that humans consisted of a small group of those of superior intelligence and a mass of inferior people, regardless of race.

Anglo-Saxons

Mencken countered the arguments for Anglo-Saxon superiority prevalent in his time in a 1923 essay entitled "The Anglo-Saxon", which argued that if there was such a thing as a pure "Anglo-Saxon" race, it was defined by its inferiority and cowardice: "The normal American of the 'pure-blooded' majority goes to rest every night with an uneasy feeling that there is a burglar under the bed and he gets up every morning with a sickening fear that his underwear has been stolen."Jews

In the 1930 edition of ''Treatise on the Gods

''Treatise on the Gods'' (1930) is H. L. Mencken's survey of the history and philosophy of religion, and was intended as an unofficial companion volume to his ''Treatise on Right and Wrong'' (1934). The first and second printings were sold out be ...

'', Mencken wrote:

That passage was removed from subsequent editions at his express direction.

Chaz Bufe Charles Bufe, better known as Chaz Bufe, is a contemporary American anarchist author. Bufe primarily writes on the problems faced by the modern anarchist movement (as in his pamphlet " Listen, Anarchist!"), and also on atheism, music theory and inte ...

, an admirer of Mencken, wrote that Mencken's various anti-Semitic statements should be understood in the context that Mencken made bombastic and over-the-top denunciations of almost any national, religious, and ethnic group. That said, Bufe still wrote that some of Mencken's statements were "odious", such as his claim in his 1918 introduction to Nietzsche's ''The Anti-Christ'' that "The case against the Jews is long and damning; it would justify ten thousand times as many pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s as now go on in the world".

Author Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal (; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his epigrammatic wit, erudition, and patrician manner. Vidal was bisexual, and in his novels and ...

later deflected claims of anti-Semitism against Mencken:

As Germany gradually conquered Europe, Mencken attacked Roosevelt for refusing to admit Jewish refugees into the United States and called for their wholesale admission:

Democracy

This sentiment is fairly consistent with Mencken's distaste for common notions and the philosophical outlook he unabashedly set down throughout his life as a writer (drawing on Friedrich Nietzsche andHerbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest" ...

, among others).

Mencken wrote as follows about the difficulties of good men reaching national office when such campaigns must necessarily be conducted remotely:The larger the mob, the harder the test. In small areas, before small electorates, a first-rate man occasionally fights his way through, carrying even the mob with him by force of his personality. But when the field is nationwide, and the fight must be waged chiefly at second and third hand, and the force of personality cannot so readily make itself felt, then all the odds are on the man who is, intrinsically, the most devious and mediocre—the man who can most easily adeptly disperse the notion that his mind is a virtual vacuum. The Presidency tends, year by year, to go to such men. As democracy is perfected, the office represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. We move toward a lofty ideal. On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart's desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.

Science and mathematics

Mencken defended the evolutionary views ofCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

but spoke unfavorably of many prominent physicists and had little regard for pure mathematics. Regarding theoretical physics

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experim ...

, he said to longtime editor Charles Angoff

Charles Angoff (April 22, 1902 – May 3, 1979) was a managing editor of the American Mercury magazine as well as a professor of English of Fairleigh Dickinson University. H. L. Mencken called him "the best managing editor in America." He wa ...

, "Imagine measuring infinity! That's a laugh."Angoff, Charles. ''H. L. Mencken: A Portrait from Memory''. A. S. Barnes (New York, 1961), p. 141

In response, Angoff said: "Well, without mathematics there wouldn't be any engineering, no chemistry, no physics." Mencken responded: "That's true, but it's reasonable mathematics. Addition, subtraction, multiplication, fractions, division, that's what real mathematics is. The rest is baloney. Astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of Celestial o ...

. Religion. All of our sciences still suffer from their former attachment to religion, and that is why there is so much metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

and astrology, the two are the same, in science."

Elsewhere, he dismissed higher mathematics and probability theory

Probability theory is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expressing it through a set o ...

as "nonsense", after he read Angoff's article for Charles S. Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for t ...

in the ''American Mercury'': "So you believe in that garbage, too—theories of knowledge, infinity, laws of probability. I can make no sense of it, and I don't believe you can either, and I don't think your god Peirce knew what he was talking about."

Mencken repeated these opinions in articles for the ''American Mercury''. He said mathematics is a fiction, compared with individual facts that make up science. In a review for Hans Vaihinger

Hans Vaihinger (; September 25, 1852 – December 18, 1933) was a German philosopher, best known as a Kant scholar and for his ''Die Philosophie des Als Ob'' ('' The Philosophy of 'As if), published in 1911 although its statement of basic ...

's ''The Philosophy of "As If",'' he said:

Mencken repeatedly identified mathematics with metaphysics and theology. According to Mencken, mathematics is necessarily infected with metaphysics. Mathematicians tend to engage in metaphysical speculation. In a review of Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He is best known as the defining figure of the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which today has found applicat ...

's ''The Aims of Education,'' Mencken remarked that, although he agreed with Whitehead's thesis and admired his writing style, "Now and then he falls into mathematical jargon and pollutes his discourse with equations", and " ere are moments when he seems to be following some of his mathematical colleagues into the gaudy metaphysics which now entertains them". For Mencken, theology was characterized by the fact that it uses correct reasoning from false premises. Mencken uses the term "theology" more generally to refer to the use of logic in science or any field of knowledge. In a review of Arthur Eddington

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He was also a philosopher of science and a populariser of science. The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the lumin ...

's ''The Nature of the Physical World'' and Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, in ...

's ''Man a Machine

''Man a Machine'' (French: ''L'homme Machine'') is a work of materialist philosophy by the 18th-century French physician and philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie, first published in 1747. In this work, de La Mettrie extends Descartes' argum ...

'', Mencken ridiculed the use of reasoning to establish any fact in science. Theologians happen to be masters of "logic" and yet are mental defectives:

Mencken wrote a review of Sir James Jeans

Sir James Hopwood Jeans (11 September 187716 September 1946) was an English physicist, astronomer and mathematician.

Early life

Born in Ormskirk, Lancashire, the son of William Tulloch Jeans, a parliamentary correspondent and author. Jeans was ...

's book, ''The Mysterious Universe'', in which Mencken wrote that mathematics is not necessary for physics. Instead of mathematical "speculation" (such as quantum theory

Quantum theory may refer to:

Science

*Quantum mechanics, a major field of physics

*Old quantum theory, predating modern quantum mechanics

* Quantum field theory, an area of quantum mechanics that includes:

** Quantum electrodynamics

** Quantum ch ...

), Mencken believed physicists should directly look at individual facts in the laboratory, as do chemists:

In the same article, which he re-printed in the ''Mencken Chrestomathy,'' Mencken primarily contrasts what real scientists do, which is to simply directly look at the existence of "shapes and forces" confronting them instead of (such as in statistics) attempting to speculate and use mathematical models. Physicists and especially astronomers are consequently not real scientists, because when looking at shapes or forces, they do not simply "patiently wait for further light", but resort to mathematical theory. There is no need for statistics in scientific physics, since one should simply look at the facts while statistics attempts to construct mathematical models. On the other hand, the really competent physicists do not bother with the "theology" or reasoning of mathematical theories (such as in quantum mechanics):

Mencken ridiculed Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

's theory of general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

, believing that "in the long run his curved space may be classed with the psychosomatic bumps of ranz JosefGall and ohannSpurzheim". In his private letters, he said:

Memorials

Home

Mencken's home at 1524 Hollins Street inBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

's Union Square

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

neighborhood, where he lived for 67 years, was bequeathed to the University of Maryland, Baltimore

The University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) is a public university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1807, it comprises some of the oldest professional schools of dentistry, law, medicine, pharmacy, social work and nursing in the United States ...

on the death of his younger brother, August, in 1967. The City of Baltimore acquired the property in 1983, and the H. L. Mencken House

The H. L. Mencken House was the home of ''Baltimore Sun'' journalist and author Henry Louis Mencken, who lived here from 1883 until his death in 1956. The Italianate brick row house at 1524 Hollins Street in Baltimore was designated a National ...

became part of the City Life Museums. It has been closed to general admission since 1997, but is opened for special events and group visits by arrangement.

Papers

Shortly afterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Mencken expressed his intention of bequeathing his books and papers to Baltimore's Enoch Pratt Free Library

The Enoch Pratt Free Library is the free public library system of Baltimore, Maryland. Its Central Library and office headquarters are located on 400 Cathedral Street (southbound) and occupy the northeastern three quarters of a city block bound ...

. At his death, it was in possession of most of the present large collection. As a result, his papers as well as much of his personal library, which includes many books inscribed by major authors, are held in the Library's Central Branch on Cathedral Street in Baltimore. The original third floor ''H. L. Mencken Room and Collection'' housing this collection was dedicated on April 17, 1956. The new Mencken Room, on the first floor of the Library's Annex, was opened in November 2003.

The collection contains Mencken's typescripts, newspaper and magazine contributions, published books, family documents and memorabilia, clipping books, large collection of presentation volumes, file of correspondence with prominent Marylanders, and the extensive material he collected while he was preparing ''The American Language

''The American Language; An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States'', first published in 1919, is H. L. Mencken's book about the English language as spoken in the United States.

Origins and concept

Mencken was inspired by ...

''.

Other Mencken related collections of note are at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native A ...

, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

, Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

, and Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

. In 2007, Johns Hopkins acquired "nearly 6,000 books, photographs and letters by and about Mencken" from "the estate of an Ohio accountant".

The Sara Haardt Mencken collection at Goucher College

Goucher College ( ') is a private liberal arts college in Towson, Maryland. It was chartered in 1885 by a conference in Baltimore led by namesake John F. Goucher and local leaders of the Methodist Episcopal Church.https://archive.org/details/h ...

includes letters exchanged between Haardt and Mencken and condolences written after her death. Some of Mencken's vast literary correspondence is held at the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

. "Gift of HL Mencken 1929" is stamped on ''The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

''The Marriage of Heaven and Hell'' is a book by the English poet and printmaker William Blake. It is a series of texts written in imitation of biblical prophecy but expressing Blake's own intensely personal Romantic and revolutionary beliefs ...

'', Luce 1906 edition of William Blake, which shows up from the Library of Congress online version for reading. Mencken's letters to Louise (Lou) Wylie, a reporter and feature writer for New Orleans's ''The Times-Picayune

''The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate'' is an American newspaper published in New Orleans, Louisiana, since January 25, 1837. The current publication is the result of the 2019 acquisition of ''The Times-Picayune'' (itself a result of th ...

'' newspaper, are archived at Loyola University New Orleans

Loyola University New Orleans is a Private university, private Jesuit university in New Orleans, New Orleans, Louisiana. Originally established as Loyola College in 1904, the institution was chartered as a university in 1912. It bears the name o ...

.

Works

Books

* '' George Bernard Shaw: His Plays'' (1905) * ''The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche

''The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche'' is a book by H. L. Mencken, the first edition in 1908. The book covers both better and lesser known areas of Friedrich Nietzsche's life and philosophy. It is notable both for its suggestion of Mencken's s ...

'' (1907)

* ''The Gist of Nietzsche'' (1910)

* ''What You Ought to Know about your Baby'' (Ghostwriter

A ghostwriter is hired to write literary or journalistic works, speeches, or other texts that are officially credited to another person as the author. Celebrities, executives, participants in timely news stories, and political leaders often h ...

for Leonard K. Hirshberg; 1910)

* ''Men versus the Man: a Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist and H. L. Mencken, Individualist'' (1910)

* ''Europe After 8:15'' (1914)

* ''A Book of Burlesques'' (1916)

* ''A Little Book in C Major'' (1916)

* '' A Book of Prefaces'' (1917)

* ''In Defense of Women

''In Defense of Women'' is H. L. Mencken's 1918 book on women and the relationship between the sexes. Some laud the book as progressive while others brand it as reactionary. While Mencken did not champion women's rights, he described women as ...

'' (1918)

* ''Damn! A Book of Calumny'' (1918)

* ''The American Language

''The American Language; An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States'', first published in 1919, is H. L. Mencken's book about the English language as spoken in the United States.

Origins and concept

Mencken was inspired by ...

'' (1919)

* Prejudices (1919–27)

** ''First Series'' (1919)

** ''Second Series'' (1920)

** ''Third Series'' (1922)

** ''Fourth Series'' (1924)

** ''Fifth Series'' (1926)

** ''Sixth Series'' (1927)

** ''Selected Prejudices'' (1927)

* ''Heliogabalus (A Buffoonery in Three Acts)'' (1920)

* ''The American Credo'' (1920)

* ''Notes on Democracy

''Notes on Democracy'' is a 1926 book by American journalist, satirist, cultural critic H. L. Mencken.

The initial print run was only 235 copies; another edition was printed later in 1926. A number of reprints of the book have continued to be is ...

'' (1926)

* '' Menckeneana: A Schimpflexikon'' (1928) – Editor

* ''Treatise on the Gods

''Treatise on the Gods'' (1930) is H. L. Mencken's survey of the history and philosophy of religion, and was intended as an unofficial companion volume to his ''Treatise on Right and Wrong'' (1934). The first and second printings were sold out be ...

'' (1930)

* ''Making a President'' (1932)

* ''Treatise on Right and Wrong'' (1934)

* ''Happy Days, 1880–1892

''Happy Days, 1880–1892'' (1940) is the first of an autobiographical trilogy by H.L. Mencken, covering his days as a child in Baltimore, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares border ...

'' (1940)

* ''Newspaper Days, 1899–1906'' (1941)

* ''A New Dictionary of Quotations on Historical Principles from Ancient and Modern Sources'' (1942)

* ''Heathen Days, 1890–1936'' (1943)

* ''Christmas Story'' (1944)

* ''The American Language, Supplement I'' (1945)

* ''The American Language, Supplement II'' (1948)

* ''A Mencken Chrestomathy'' (1949) (edited by H.L. Mencken)

Posthumous collections

* ''Minority Report'' (1956)

* ''On Politics: A Carnival of Buncombe'' (1956)

* .

* ''The Bathtub Hoax and Other Blasts and Bravos from the Chicago Tribune'' (1958)

* .

* .

* .

* ''A Second Mencken Chrestomathy'' (1994) (edited by Terry Teachout

Terrance Alan Teachout (February 6, 1956 – January 13, 2022) was an American author, critic, biographer, playwright, stage director, and librettist.

He was the drama critic of ''The Wall Street Journal'', the critic-at-large of ''Commentary'' ...

)

* ''Thirty-five Years of Newspaper Work'' (1996)

* .

Chapbooks, pamphlets, and notable essays

* ''Ventures into Verse'' (1903) * ''The Artist: A Drama Without Words'' (1912) * ''The Creed of a Novelist'' (1916) * ''Pistols for Two'' (1917) *The Sahara of the Bozart

'' (1920) * '' Gamalielese'' (1921) *

The Hills of Zion

(1925) * '' The Libido for the Ugly'' (1927) * The Penalty of Death

See also

* Bathtub hoax * ''Elmer Gantry

''Elmer Gantry'' is a satirical novel written by Sinclair Lewis in 1926 that presents aspects of the religious activity of America in fundamentalist and evangelistic circles and the attitudes of the 1920s public toward it. The novel's protagonis ...

'', a 1927 satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

novel dedicated to Mencken by Sinclair Lewis