Greek Love on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Greek love'' is a term originally used by

Male same-sex relationships of the kind portrayed by the "Greek love" ideal were increasingly disallowed within the

Male same-sex relationships of the kind portrayed by the "Greek love" ideal were increasingly disallowed within the

Homosexuality and Civilization

'. Harvard University Press, 2006. In the postclassical period, love poetry addressed by males to other males has been in general taboo.Crompton, Louis. ''Byron and Greek Love: Homophobia in 19th-century England''. Faber & Faber, London 1985. According to Reeser's book "Setting Plato Straight", it was the Renaissance that shifted the idea of love in Plato's sense to what we now refer to as "Platonic love"—as asexual and heterosexual. In 1469, the

The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art, and Homosexual Fantasy

' (Routledge, 1993) Ficino is "perhaps the most important Platonic commentator and teacher in the Renaissance". The ''Symposium'' became the most important text for conceptions of love in general during the

The German term ''griechische Liebe'' ("Greek love") appears in German literature between 1750 and 1850, along with ''socratische Liebe'' ("Socratic love") and ''platonische Liebe'' (" Platonic love") in reference to male-male attractions. The work of the German art historian

The German term ''griechische Liebe'' ("Greek love") appears in German literature between 1750 and 1850, along with ''socratische Liebe'' ("Socratic love") and ''platonische Liebe'' (" Platonic love") in reference to male-male attractions. The work of the German art historian  German 18th-century works from the "Greek love" milieu of classical studies include the academic essays of

German 18th-century works from the "Greek love" milieu of classical studies include the academic essays of

The concept of Greek love was important to two of the most significant poets of English

The concept of Greek love was important to two of the most significant poets of English  Shelley complained that contemporary reticence about homosexuality kept modern readers without a knowledge of the original languages from understanding a vital part of ancient Greek life. His poetry was influenced by the "androgynous male beauty" represented in Winckelmann's art history. Shelley wrote his ''Discourse on the Manners of the Antient Greeks Relative to the Subject of Love'' on the Greek conception of love in 1818 during his first summer in Italy, concurrently with his translation of Plato's ''Symposium''. Shelley was the first major English writer to analyse Platonic homosexuality, although neither work was published during his lifetime. His translation of the ''Symposium'' did not appear in complete form until 1910.

Shelley asserts that Greek love arose from the circumstances of Greek households, in which women were not educated and not treated as equals, and thus not suitable objects of ideal love.

Although Shelley recognised the homosexual nature of the love relationships between males in ancient Greece, he argued that homosexual lovers often engaged in no behaviour of a sexual nature, and that Greek love was based on the intellectual component, in which one seeks a complementary beloved. He maintains that the immorality of the homosexual acts are on par with the immorality of contemporary prostitution, and contrasts the pure version of Greek love with the later licentiousness found in Roman culture. Shelley cites Shakespeare's sonnets as another expression of the same sentiments, and ultimately argues that they are chaste and platonic in nature.

Shelley complained that contemporary reticence about homosexuality kept modern readers without a knowledge of the original languages from understanding a vital part of ancient Greek life. His poetry was influenced by the "androgynous male beauty" represented in Winckelmann's art history. Shelley wrote his ''Discourse on the Manners of the Antient Greeks Relative to the Subject of Love'' on the Greek conception of love in 1818 during his first summer in Italy, concurrently with his translation of Plato's ''Symposium''. Shelley was the first major English writer to analyse Platonic homosexuality, although neither work was published during his lifetime. His translation of the ''Symposium'' did not appear in complete form until 1910.

Shelley asserts that Greek love arose from the circumstances of Greek households, in which women were not educated and not treated as equals, and thus not suitable objects of ideal love.

Although Shelley recognised the homosexual nature of the love relationships between males in ancient Greece, he argued that homosexual lovers often engaged in no behaviour of a sexual nature, and that Greek love was based on the intellectual component, in which one seeks a complementary beloved. He maintains that the immorality of the homosexual acts are on par with the immorality of contemporary prostitution, and contrasts the pure version of Greek love with the later licentiousness found in Roman culture. Shelley cites Shakespeare's sonnets as another expression of the same sentiments, and ultimately argues that they are chaste and platonic in nature.

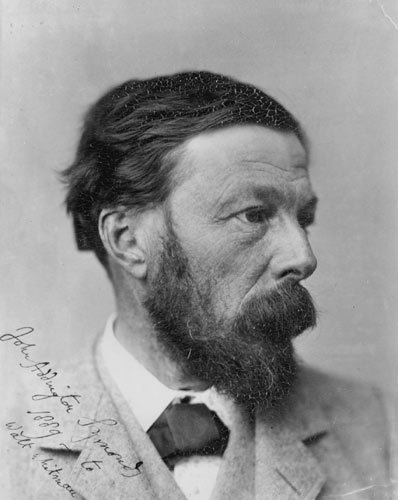

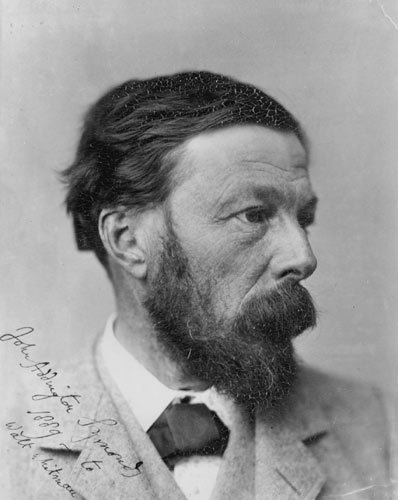

In 1873, the poet and literary critic John Addington Symonds wrote ''A Problem in Greek Ethics'', a work of what could later be called "

In 1873, the poet and literary critic John Addington Symonds wrote ''A Problem in Greek Ethics'', a work of what could later be called "

classicists

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

to describe the primarily homoerotic

Homoeroticism is sexual attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female. The concept differs from the concept of homosexuality: it refers specifically to the desire itself, which can be temporary, whereas "homose ...

customs, practices, and attitudes of the ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

. It was frequently used as a euphemism for homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

and pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and an ...

. The phrase is a product of the enormous impact of the reception

Reception is a noun form of ''receiving'', or ''to receive'' something, such as art, experience, information, people, products, or vehicles. It may refer to:

Astrology

* Reception (astrology), when a planet is located in a sign ruled by another ...

of classical Greek culture on historical attitudes toward sexuality, and its influence on art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

and various intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

movements.Blanshard, Alastair J. L. ''Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010)

'Greece' as the historical memory of a treasured past was romanticised and idealised as a time and a culture when love between males was not only tolerated but actually encouraged, and expressed as the high ideal of same-sex camaraderie. ... If tolerance and approval ofFollowing the work of sexuality theorist Michel Foucault, the validity of an ancient Greek model for modernmale homosexuality Human male sexuality encompasses a wide variety of feelings and behaviors. Men's feelings of attraction may be caused by various physical and social traits of their potential partner. Men's sexual behavior can be affected by many factors, incl ...had happened once—and in a culture so much admired and imitated by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—might it not be possible to replicate inmodernity Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the "Age of Reas ...the antique homeland of the non-heteronormative Heteronormativity is the concept that heterosexuality is the preferred or normal mode of sexual orientation. It assumes the gender binary (i.e., that there are only two distinct, opposite genders) and that sexual and marital relations are most ...?

gay culture

Gay men are male homosexuals. Some bisexual and homoromantic men may also dually identify as gay, and a number of young gay men also identify as queer. Historically, gay men have been referred to by a number of different terms, including '' ...

has been questioned.Blanshard, Alastair J. L. "Greek Love," essay at p. 161 of Eriobon, Didier ''Insult and the Making of the Gay Self'', transl. Lucey M. (Duke University Press, 2004 In his essay "Greek Love", Alastair Blanshard sees "Greek love" as "one of the defining and divisive issues in the homosexual rights movement.

Historic terms

As a phrase in Modern English and other modern European languages, "Greek love" refers to various (mostly homoerotic) practices as part of the Hellenic heritage reinterpreted by adherents such asLytton Strachey

Giles Lytton Strachey (; 1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was an English writer and critic. A founding member of the Bloomsbury Group and author of '' Eminent Victorians'', he established a new form of biography in which psychological insight ...

; quotation marks

Quotation marks (also known as quotes, quote marks, speech marks, inverted commas, or talking marks) are punctuation marks used in pairs in various writing systems to set off direct speech, a quotation, or a phrase. The pair consists of an ...

are often placed on either or both words ("Greek" love, Greek "love", or "Greek love") to indicate that usage of the phrase is determined by context. It often serves as a "coded phrase" for pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and an ...

, or to "sanitize" homosexual desire in historical contexts where it was considered unacceptable.

The German term ''griechische Liebe'' ("Greek love") appears in German literature between 1750 and 1850, along with ''socratische Liebe'' ("Socratic love") and ''platonische Liebe'' (" Platonic love") in reference to male-male attractions. Ancient Greece became a positive reference point by which homosexual men of a certain class and education could engage in discourse that might otherwise be taboo. In the early Modern period, a disjuncture was carefully maintained between idealized male eros

In Greek mythology, Eros (, ; grc, Ἔρως, Érōs, Love, Desire) is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid ("desire").''Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia'', The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215. In the ear ...

in the classical tradition, which was treated with reverence, and sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''sod ...

, which was a term of contempt.

Ancient Greek background

In his classic study ''Greek Homosexuality'',Kenneth Dover

Sir Kenneth James Dover, (11 March 1920 – 7 March 2010) was a distinguished British classical scholar and academic. He was president of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, from 1976 to 1986. In addition, he was president of the British Academy fro ...

states that the English nouns "a homosexual" and "a heterosexual

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" ...

" have no equivalent in the ancient Greek language

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

. According to Dover, there was no concept in ancient Greece equivalent to the modern conception of "sexual preference"; it was assumed that a person could have both hetero- and homosexual responses at different times. Dover, Kenneth J., ''Greek Homosexuality'' (Harvard University Press, 1978, 1989) Evidence for same-sex attractions and behaviors is more abundant for men than for women. Both romantic love and sexual passion between men were often considered normal, and under some circumstances healthy or admirable. The most common male-male relationship was '' paiderasteia'', a socially-acknowledged institution in which a mature male ('' erastēs'', the active lover) bonded with or mentored a teen-aged youthSacks, David, ''A Dictionary of the Ancient Greek World'' (Oxford University Press, 1995) (''eromenos

In ancient Greece, an ''eromenos'' was the younger and passive (or 'receptive') partner in a male homosexual relationship. The partner of an ''eromenos'' was the ''erastes'', the older and active partner. The ''eromenos'' was often depicted as a ...

'', the passive lover, or ''pais'', "boy" understood as an endearment and not necessarily a category of age ). Martin Litchfield West

Martin Litchfield West, (23 September 1937 – 13 July 2015) was a British philologist and classical scholar. In recognition of his contribution to scholarship, he was awarded the Order of Merit in 2014.

West wrote on ancient Greek music, Gr ...

views Greek pederasty as "a substitute for heterosexual love, free contacts between the sexes being restricted by society".

Greek art

Greek art began in the Cycladic and Minoan civilization, and gave birth to Western classical art in the subsequent Geometric, Archaic and Classical periods (with further developments during the Hellenistic Period). It absorbed influences of E ...

and literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

portray these relationships as sometimes erotic or sexual, or sometimes idealized, educational, non-consummated, or non-sexual. A distinctive feature of Greek male-male eros

In Greek mythology, Eros (, ; grc, Ἔρως, Érōs, Love, Desire) is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid ("desire").''Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia'', The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215. In the ear ...

was its occurrence within a military setting, as with the Theban Band, though the extent to which homosexual bonds played a military role has been questioned.

Some Greek myths have been interpreted as reflecting the custom of ''paiderasteia'', most notably the myth of Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek reli ...

kidnapping Ganymede to become his cupbearer in the Olympian symposium. The death of Hyacinthus is also frequently referenced as a pederastic myth.

The main Greek literary sources for Greek homosexuality are lyric poetry, Athenian comedy, the works of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

, and courtroom speeches from Athens. Vase paintings from the 500s and 400s BCE depict courtship and sex between males.

Ancient Rome

InLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, ''mos Graeciae'' or ''mos Graecorum'' ("Greek custom" or "the way of the Greeks") refers to a variety of behaviors the ancient Romans regarded as Greek, including but not confined to sexual practice. Homosexual behaviors at Rome were acceptable only within an inherently unequal relationship; male Roman citizens retained their masculinity as long as they took the active, penetrating role, and the appropriate male sexual partner was a prostitute or slave, who would nearly always be non-Roman. In Archaic and classical Greece, ''paiderasteia'' had been a formal social relationship between freeborn males; taken out of context and refashioned as the luxury product of a conquered people, pederasty came to express roles based on domination and exploitation.Pollini, John, "The Warren Cup: Homoerotic Love and Symposial Rhetoric in Silver", in ''Art Bulletin'' 81.1 (1999) Slaves often were given, and prostitutes sometimes assumed, Greek names regardless of their ethnic origin; the boys ''( pueri)'' to whom the poet Martial is attracted have Greek names. The use of slaves defined Roman pederasty; sexual practices were "somehow 'Greek when they were directed at "freeborn boys openly courted in accordance with the Hellenic tradition of pederasty".

Effeminacy or a lack of discipline in managing one's sexual attraction to another male threatened a man's "Roman-ness" and thus might be disparaged as "Eastern" or "Greek". Fears that Greek models might "corrupt" traditional Roman social codes (the '' mos maiorum'') seem to have prompted a vaguely documented law ('' Lex Scantinia'') that attempted to regulate aspects of homosexual relationships between freeborn males and to protect Roman youth from older men emulating Greek customs of pederasty.

By the close of the 2nd century BCE, however, the elevation of Greek literature

Greek literature () dates back from the ancient Greek literature, beginning in 800 BC, to the modern Greek literature of today.

Ancient Greek literature was written in an Ancient Greek dialect, literature ranges from the oldest surviving writte ...

and art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

as models of expression caused homoeroticism to be regarded as urbane and sophisticated. The consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

Quintus Lutatius Catulus

Quintus Lutatius Catulus (149–87 BC) was a consul of the Roman Republic in 102 BC. His consular colleague was Gaius Marius. During their consulship the Cimbri and Teutones marched south again and threatened the Republic. While Marius marched ag ...

was among a circle of poets who made short, light Hellenistic poems fashionable in the late Republic. One of his few surviving fragments is a poem of desire addressed to a male with a Greek name, signaling the new aesthetic in Roman culture. The Hellenization

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the H ...

of elite culture influenced sexual attitudes among "avant-garde, philhellenic Romans", as distinguished from sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

or behavior, and came to fruition in the "new poetry

''The New Poetry'' is a poetry anthology edited by Al Alvarez, published in 1962 and in a revised edition in 1966. It was greeted at the time as a significant review of the post-war scene in English poetry.

The introduction, written by Alvare ...

" of the 50s BCE. The poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His s ...

, written in forms adapted from Greek meters, include several expressing desire for a freeborn youth explicitly named "Youth" (''Iuventius''). His Latin name and free-born status subvert pederastic tradition at Rome. Catullus's poems are more often addressed to a woman.

The literary ideal celebrated by Catullus stands in contrast to the practice of elite Romans who kept a ''puer delicatus

Homosexuality in ancient Rome often differs markedly from the contemporary West. Latin lacks words that would precisely translate " homosexual" and "heterosexual". The primary dichotomy of ancient Roman sexuality was active/ dominant/masculine ...

'' ("exquisite boy") as a form of high-status sexual consumption, a practice that continued well into the Imperial era. The ''puer delicatus'' was a slave chosen from the pages who served in a high-ranking household. He was selected for his good looks and grace to serve at his master's side, where he is often depicted in art. Among his duties, at a '' convivium'' he would enact the Greek mythological

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of d ...

role of Ganymede, the Trojan

Trojan or Trojans may refer to:

* Of or from the ancient city of Troy

* Trojan language, the language of the historical Trojans

Arts and entertainment Music

* ''Les Troyens'' ('The Trojans'), an opera by Berlioz, premiered part 1863, part 189 ...

youth abducted by Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek reli ...

to serve as a divine cupbearer

A cup-bearer was historically an officer of high rank in royal courts, whose duty was to pour and serve the drinks at the royal table. On account of the constant fear of plots and intrigues (such as poisoning), a person must have been regarded as ...

. Attacks on emperors such as Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

and Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 11/12 March 222), better known by his nickname "Elagabalus" (, ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short reign was conspicuous for s ...

, whose young male partners accompanied them in public for official ceremonies, criticized the perceived "Greekness" of male-male sexuality. Vout C., ''Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome'', Cambridge University Press (2007) "Greek love", or the cultural model of Greek pederasty in ancient Rome, is a "topos

In mathematics, a topos (, ; plural topoi or , or toposes) is a category that behaves like the category of sheaves of sets on a topological space (or more generally: on a site). Topoi behave much like the category of sets and possess a notio ...

or literary game" that "never stops being Greek in the Roman imagination", an erotic pose to be distinguished from the varieties of real-world sexuality among individuals. Vout sees the views of Williams and MacMullen as opposite extremes on the subject

Renaissance

Male same-sex relationships of the kind portrayed by the "Greek love" ideal were increasingly disallowed within the

Male same-sex relationships of the kind portrayed by the "Greek love" ideal were increasingly disallowed within the Judaeo-Christian

The term Judeo-Christian is used to group Christianity and Judaism together, either in reference to Christianity's derivation from Judaism, Christianity's borrowing of Jewish Scripture to constitute the "Old Testament" of the Christian Bible, or ...

traditions of western society.Crompton, Louis. Homosexuality and Civilization

'. Harvard University Press, 2006. In the postclassical period, love poetry addressed by males to other males has been in general taboo.Crompton, Louis. ''Byron and Greek Love: Homophobia in 19th-century England''. Faber & Faber, London 1985. According to Reeser's book "Setting Plato Straight", it was the Renaissance that shifted the idea of love in Plato's sense to what we now refer to as "Platonic love"—as asexual and heterosexual. In 1469, the

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

Marsilio Ficino reintroduced Plato's ''Symposium'' to western culture with his Latin translation titled ''De Amore'' ("On Love").Berry, Phillippa. ''Of Chastity and Power: Elizabethan Literature and the Unmarried Queen'' (Routledge, 1989, 1994) Aldrich, Robert. The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art, and Homosexual Fantasy

' (Routledge, 1993) Ficino is "perhaps the most important Platonic commentator and teacher in the Renaissance". The ''Symposium'' became the most important text for conceptions of love in general during the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

. In his commentary

Commentary or commentaries may refer to:

Publications

* ''Commentary'' (magazine), a U.S. public affairs journal, founded in 1945 and formerly published by the American Jewish Committee

* Caesar's Commentaries (disambiguation), a number of works ...

on Plato, Ficino interprets ''amor platonicus'' (" Platonic love") and ''amor socraticus'' ("Socratic love") allegorically as idealized male love, in keeping with the Church doctrine of his time. Ficino's interpretation of the ''Symposium'' influenced a philosophical view that the pursuit of knowledge, particularly self-knowledge, required the sublimation of sexual desire. Ficino thus began the long historical process of suppressing the homoeroticism of in particular, the dialogue ''Charmides'' "threatens to expose the carnal nature of Greek love" which Ficino sought to minimize.

For Ficino, "Platonic love" was a bond between two men that fosters a shared emotional and intellectual life, as distinguished from the "Greek love" practiced historically as the '' erastes/eromenos

In ancient Greece, an ''eromenos'' was the younger and passive (or 'receptive') partner in a male homosexual relationship. The partner of an ''eromenos'' was the ''erastes'', the older and active partner. The ''eromenos'' was often depicted as a ...

'' relationship. Ficino thus points toward the modern usage of "Platonic love" to mean love without sexuality. In his commentary to the ''Symposium'', Ficino carefully separates the act of sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''sod ...

, which he condemned, and praises Socratic love as the highest form of friendship. Ficino maintained that men could use each other's beauty and friendship to discover the greatest good, that is, God, and thus Christianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

idealized male love as expressed by Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

.

During the Renaissance, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

and Michelangelo used Plato's philosophy as inspiration for some of their greatest works. The "rediscovery" of classical antiquity was perceived as a liberating experience, and Greek love as an ideal after a Platonic model. Michelangelo presented himself to the public as a Platonic lover of men, combining Catholic orthodoxy and pagan enthusiasm in his portrayal of the male form, most notably the ''David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

'', but his great-nephew edited his poems to diminish references to his love for Tommaso Cavalieri.

By contrast, the French Renaissance

The French Renaissance was the cultural and artistic movement in France between the 15th and early 17th centuries. The period is associated with the pan-European Renaissance, a word first used by the French historian Jules Michelet to define th ...

essayist Montaigne, whose view of love and friendship was humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

and rationalist, rejected "Greek love" as a model in his essay "De l'amitié" ("On Friendship"); it did not accord with the social needs of his own time, he wrote, because it involved "a necessary disparity in age and such a difference in the lovers' functions". Because Montaigne saw friendship as a relationship between equals in the context of political liberty

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", ''Between Past and F ...

, this inequality diminished the value of Greek love. The physical beauty and sexual attraction inherent in the Greek model for Montaigne were not necessary conditions of friendship, and he dismisses homosexual relations, which he refers to as ''licence grecque'', as socially repulsive. Although the wholesale importation of a Greek model would be socially improper, ''licence grecque'' seems to refer only to licentious homosexual conduct, in contrast to the moderate behavior between men in the perfect friendship. When Montaigne chooses to introduce his essay on friendship with recourse to the Greek model, "homosexuality's role as trope

Trope or tropes may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Trope (cinema), a cinematic convention for conveying a concept

* Trope (literature), a figure of speech or common literary device

* Trope (music), any of a variety of different things ...

is more important than its status as actual male-male desire or act ... ''licence grecque'' becomes an aesthetic device to frame the center."

Neoclassicism

German Hellenism

The German term ''griechische Liebe'' ("Greek love") appears in German literature between 1750 and 1850, along with ''socratische Liebe'' ("Socratic love") and ''platonische Liebe'' (" Platonic love") in reference to male-male attractions. The work of the German art historian

The German term ''griechische Liebe'' ("Greek love") appears in German literature between 1750 and 1850, along with ''socratische Liebe'' ("Socratic love") and ''platonische Liebe'' (" Platonic love") in reference to male-male attractions. The work of the German art historian Johann Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (; ; 9 December 17178 June 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the differences between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and founding he ...

was a major influence on the formation of classical ideals in the 18th century, and is also a frequent starting point for histories of gay German literature.Robert Tobin, "German Literature", in ''Gay Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia'' (Taylor & Francis, 2000) Winckelmann observed the inherent homoeroticism of Greek art

Greek art began in the Cycladic and Minoan civilization, and gave birth to Western classical art in the subsequent Geometric, Archaic and Classical periods (with further developments during the Hellenistic Period). It absorbed influences of E ...

, though he felt he had to leave much of this perception implicit: "I should have been able to say more if I had written for the Greeks, and not in a modern tongue, which imposed on me certain restrictions." His own homosexuality influenced his response to Greek art and often tended toward the rhapsodic: "from admiration I pass to ecstasy ...," he wrote of the Apollo Belvedere

The ''Apollo Belvedere'' (also called the ''Belvedere Apollo, Apollo of the Belvedere'', or ''Pythian Apollo'') is a celebrated marble sculpture from Classical Antiquity.

The ''Apollo'' is now thought to be an original Roman creation of Hadri ...

, "I am transported to Delos and the sacred grove

Sacred groves or sacred woods are groves of trees and have special religious importance within a particular culture. Sacred groves feature in various cultures throughout the world. They were important features of the mythological landscape and ...

s of Lycia

Lycia ( Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is ...

—places Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

honoured with his presence—and the statue seems to come alive like the beautiful creation of Pygmalion

Pygmalion or Pigmalion may refer to:

Mythology

* Pygmalion (mythology), a sculptor who fell in love with his statue

Stage

* ''Pigmalion'' (opera), a 1745 opera by Jean-Philippe Rameau

* ''Pygmalion'' (Rousseau), a 1762 melodrama by Jean-Jacques ...

." Although now regarded as "ahistorical and utopian", his approach to art history provided a "body" and "set of trope

Trope or tropes may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Trope (cinema), a cinematic convention for conveying a concept

* Trope (literature), a figure of speech or common literary device

* Trope (music), any of a variety of different things ...

s" for Greek love, "a semantics

Semantics (from grc, σημαντικός ''sēmantikós'', "significant") is the study of reference, meaning, or truth. The term can be used to refer to subfields of several distinct disciplines, including philosophy, linguistics and comp ...

surrounding Greek love that ... feeds into the related eighteenth-century discourses on friendship and love".

Winckelmann inspired German poets

This list contains the names of individuals (of any ethnicity or nationality) who wrote poetry in the German language. Most are identified as "German poets", but some are not German.

A

*Abraham a Sancta Clara

Abraham a Sancta Clara (July 2, 1 ...

in the latter 18th and throughout the 19th century, including Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

, who pointed to Winckelmann's glorification of the nude male youth in ancient Greek sculpture

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monument ...

as central to a new aesthetics of the time, and for whom Winckelmann himself was a model of Greek love as a superior form of friendship. While Winckelmann did not invent the euphemism "Greek love" for homosexuality, he has been characterized as an "intellectual midwife" for the Greek model as an aesthetic and philosophical ideal that shaped the 18th-century homosocial

In sociology, homosociality means same-sex relationships that are not of a romantic or sexual nature, such as friendship, mentorship, or others. Researchers who use the concept mainly do so to explain how men uphold men's dominance in society.

...

"cult of friendship".

German 18th-century works from the "Greek love" milieu of classical studies include the academic essays of

German 18th-century works from the "Greek love" milieu of classical studies include the academic essays of Christoph Meiners

Christoph Meiners (31 July 1747 – 1 May 1810) was a German racialist, philosopher, historian, and writer born in Warstade. He supported the polygenist theory of human origins. He was a member of the Göttingen School of History.

Biogra ...

and Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

, the parodic poem "Juno and Ganymede" by Christoph Martin Wieland, and '' A Year in Arcadia: Kyllenion'' (1805), a novel about an explicitly male-male love affair in a Greek setting by Augustus, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg

Augustus, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (full name: ''Emil Leopold August'') (23 November 1772 — 17 May 1822), was a Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, and the author of one of the first modern novels to treat of homoerotic love. He was the maternal ...

.

French Neoclassicism

Neoclassical works of art often represented ancient society and an idealized form of "Greek love". Jacques-Louis David's ''Death of Socrates'' is meant to be a "Greek" painting, imbued with an appreciation of "Greek love", a tribute and documentation of leisured, disinterested, masculine fellowship.English Romanticism

The concept of Greek love was important to two of the most significant poets of English

The concept of Greek love was important to two of the most significant poets of English Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

and Shelley. During the Regency era

The Regency era of British history officially spanned the years 1811 to 1820, though the term is commonly applied to the longer period between and 1837. King George III succumbed to mental illness in late 1810 and, by the Regency Act 1811, h ...

in which they lived, homosexuality was looked upon with increased disfavour and denounced by many in the general public, in line with the encroachment of Victorian values into the public mainstream. The terms "homosexual" and "gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

" were not used during this period, but "Greek love" among Byron's contemporaries became a way to conceptualize homosexuality, otherwise taboo, within the precedents of a highly esteemed classical past. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

, for instance, appealed to social models of classical antiquity, such as the homoerotic bonds of the Theban Band and pederasty, to demonstrate how these relationships did not inherently erode heterosexual marriages or the family structure.

The high regard for classical antiquity in the 18th century caused some adjustment in homophobic

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred or antipathy, m ...

attitudes on the Continent

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

. In Germany, the prestige of classical philology

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

led eventually to more honest translations and essays that examined the homoeroticism of Greek culture, particularly pederasty, in the context of scholarly inquiry rather than moral condemnation. An English archbishop penned what may be the most effusive account of Greek pederasty available in English at the time, duly noted by Byron on the "List of Historical Writers Whose Works I Have Perused" that he drew up at age 19.

Plato was little read in Byron's time, in contrast to the later Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

when translations of the '' Symposium'' and '' Phaedrus'' would have been the most likely way for a young student to learn about Greek sexuality. The one English translation of the ''Symposium'', published in two parts in 1761 and 1767, was an ambitious undertaking by the scholar Floyer Sydenham, who nevertheless was at pains to suppress its homoeroticism: Sydenham regularly translated the word ''eromenos

In ancient Greece, an ''eromenos'' was the younger and passive (or 'receptive') partner in a male homosexual relationship. The partner of an ''eromenos'' was the ''erastes'', the older and active partner. The ''eromenos'' was often depicted as a ...

'' as "mistress", and "boy" often becomes "maiden" or "woman". At the same time, the classical curriculum in English schools passed over works of history and philosophy in favor of Latin and Greek poetry that often dealt with erotic themes.

In describing homoerotic aspects of Byron's life and work, Louis Crompton uses the umbrella term "Greek love" to cover literary and cultural models of homosexuality from classical antiquity as a whole, both Greek and Roman, as received by intellectuals, artists, and moralists of the time. To those such as Byron who were steeped in classical literature, the phrase "Greek love" evoked pederastic myths such as Ganymede and Hyacinthus, as well as historical figures such as the political martyrs Harmodius and Aristogeiton

Harmodius (Greek: Ἁρμόδιος, ''Harmódios'') and Aristogeiton (Ἀριστογείτων, ''Aristogeíton''; both died 514 BC) were two lovers in Classical Athens who became known as the Tyrannicides (τυραννόκτονοι, ''tyranno ...

, and Hadrian's beloved Antinous; Byron refers to all these stories in his writings. He was even more familiar with the classical tradition of male love in Latin literature, and quoted or translated homoerotic passages from Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His ...

, Horace, Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, and Petronius, whose name "was a byword for homosexuality in the eighteenth century". In Byron's circle at Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

, "Horatian" was a code word for " bisexual". In correspondence, Byron and his friends resorted to the code of classical allusion

Allusion is a figure of speech, in which an object or circumstance from unrelated context is referred to covertly or indirectly. It is left to the audience to make the direct connection. Where the connection is directly and explicitly stated (as ...

s, in one exchange referring with elaborate pun

A pun, also known as paronomasia, is a form of word play that exploits multiple meanings of a term, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect. These ambiguities can arise from the intentional use of homophoni ...

s to "Hyacinths" who might be struck by coits

Quoits ( or ) is a traditional game which involves the throwing of metal, rope or rubber rings over a set distance, usually to land over or near a spike (sometimes called a hob, mott or pin). The game of quoits encompasses several distinct vari ...

, as the mythological Hyacinthus was accidentally felled while throwing the discus with Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

.

Shelley complained that contemporary reticence about homosexuality kept modern readers without a knowledge of the original languages from understanding a vital part of ancient Greek life. His poetry was influenced by the "androgynous male beauty" represented in Winckelmann's art history. Shelley wrote his ''Discourse on the Manners of the Antient Greeks Relative to the Subject of Love'' on the Greek conception of love in 1818 during his first summer in Italy, concurrently with his translation of Plato's ''Symposium''. Shelley was the first major English writer to analyse Platonic homosexuality, although neither work was published during his lifetime. His translation of the ''Symposium'' did not appear in complete form until 1910.

Shelley asserts that Greek love arose from the circumstances of Greek households, in which women were not educated and not treated as equals, and thus not suitable objects of ideal love.

Although Shelley recognised the homosexual nature of the love relationships between males in ancient Greece, he argued that homosexual lovers often engaged in no behaviour of a sexual nature, and that Greek love was based on the intellectual component, in which one seeks a complementary beloved. He maintains that the immorality of the homosexual acts are on par with the immorality of contemporary prostitution, and contrasts the pure version of Greek love with the later licentiousness found in Roman culture. Shelley cites Shakespeare's sonnets as another expression of the same sentiments, and ultimately argues that they are chaste and platonic in nature.

Shelley complained that contemporary reticence about homosexuality kept modern readers without a knowledge of the original languages from understanding a vital part of ancient Greek life. His poetry was influenced by the "androgynous male beauty" represented in Winckelmann's art history. Shelley wrote his ''Discourse on the Manners of the Antient Greeks Relative to the Subject of Love'' on the Greek conception of love in 1818 during his first summer in Italy, concurrently with his translation of Plato's ''Symposium''. Shelley was the first major English writer to analyse Platonic homosexuality, although neither work was published during his lifetime. His translation of the ''Symposium'' did not appear in complete form until 1910.

Shelley asserts that Greek love arose from the circumstances of Greek households, in which women were not educated and not treated as equals, and thus not suitable objects of ideal love.

Although Shelley recognised the homosexual nature of the love relationships between males in ancient Greece, he argued that homosexual lovers often engaged in no behaviour of a sexual nature, and that Greek love was based on the intellectual component, in which one seeks a complementary beloved. He maintains that the immorality of the homosexual acts are on par with the immorality of contemporary prostitution, and contrasts the pure version of Greek love with the later licentiousness found in Roman culture. Shelley cites Shakespeare's sonnets as another expression of the same sentiments, and ultimately argues that they are chaste and platonic in nature.

Victorian era

Throughout the 19th century, upper-class men of same-sex orientation or sympathies regarded "Greek love", often used as a euphemism for the ancient pederastic relationship between a man and a youth, as a "legitimating ideal": "the prestige of Greece among educated middle-classVictorians

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian ...

... was so massive that invocations of Hellenism could cast a veil of respectability over even a hitherto unmentionable vice or crime."Dowling, Linda. ''Hellenism and Homosexuality in Victorian Oxford'' (Cornell University Press, 1994) Homosexuality emerged as a category of thought during the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

in relation to classical studies and "manly" nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

; the discourse of "Greek love" during this time generally excluded women's sexuality. Late Victorian writers such as Walter Pater

Walter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 – 30 July 1894) was an English essayist, art critic and literary critic, and fiction writer, regarded as one of the great stylists. His first and most often reprinted book, ''Studies in the History of the Re ...

, Oscar Wilde, and John Addington Symonds saw in "Greek love" a way to introduce individuality and diversity within their own civilization. Pater's short story "Apollo in Picardy" is set at a fictional monastery where a pagan stranger named Apollyon causes the death of the young novice Hyacinth; the monastery "maps Greek love" as the site of a potential "homoerotic community" within Anglo-Catholicism

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglican ...

. Others who addressed the subject of Greek love in letters, essays, and poetry include Arthur Henry Hallam

Arthur Henry Hallam (1 February 1811 – 15 September 1833) was an English poet, best known as the subject of a major work, '' In Memoriam'', by his close friend and fellow poet Alfred Tennyson. Hallam has been described as the ''jeune homme fat ...

.

The efforts among aesthetes and intellectuals to legitimate various forms of homosexual behaviors and attitudes by virtue of a Hellenic model were not without opposition. The 1877 essay "The Greek Spirit in Modern Literature" by Richard St. John Tyrwhitt warned against the perceived immorality of this agenda. Tyrwhitt, who was a vigorous supporter of studying Greek, characterized the Hellenism of his day as "the total denial of any moral restraint on any human impulses", and outlined what he saw as the proper scope of Greek influence on the education of young men. Tyrwhitt and other critics attacked by name several scholars and writers who had tried to use Plato to support an early gay-rights agenda and whose careers were subsequently damaged by their association with "Greek love".

Symonds and Greek ethics

In 1873, the poet and literary critic John Addington Symonds wrote ''A Problem in Greek Ethics'', a work of what could later be called "

In 1873, the poet and literary critic John Addington Symonds wrote ''A Problem in Greek Ethics'', a work of what could later be called "gay history

Societal attitudes towards same-sex relationships have varied over time and place, from requiring all males to engage in same-sex relationships to casual integration, through acceptance, to seeing the practice as a minor sin, repressing it throu ...

", inspired by the poetry of Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

. The work, "perhaps the most exhaustive eulogy of Greek love",DeJean, "Sex and Philology", p. 139. remained unpublished for a decade, and then was printed at first only in a limited edition for private distribution. Symonds's approach throughout most of the essay is primarily philological

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as t ...

. He treats "Greek love" as central to Greek "aesthetic morality". Aware of the taboo nature of his subject matter, Symonds referred obliquely to pederasty as "that unmentionable custom" in a letter to a prospective reader of the book, but defined "Greek love" in the essay itself as "a passionate and enthusiastic attachment subsisting between man and youth, recognised by society and protected by opinion, which, though it was not free from sensuality, did not degenerate into mere licentiousness".

Symonds studied classics under Benjamin Jowett

Benjamin Jowett (, modern variant ; 15 April 1817 – 1 October 1893) was an English tutor and administrative reformer in the University of Oxford, a theologian, an Anglican cleric, and a translator of Plato and Thucydides. He was Master of B ...

at Balliol College, Oxford, and later worked with Jowett on an English translation of Plato's ''Symposium''. When Jowett was critical of Symonds' opinions on sexuality, Dowling notes that Jowett, in his lectures and introductions, discussed love between men and women when Plato himself had been talking about the Greek love for boys. Symonds asserted that "Greek love was for Plato no 'figure of speech', but a present and poignant reality. Greek love is for modern studies of Plato no 'figure of speech' and no anachronism, but a present poignant reality." Symonds struggled against the desexualization of " Platonic love", and sought to debunk the association of effeminacy with homosexuality by advocating a Spartan-inspired view of male love as contributing to military and political bonds. When Symonds was falsely accused of corrupting choirboys, Jowett supported him, despite his own equivocal views of the relation of Hellenism to contemporary legal and social issues that affected homosexuals.

Symonds also translated classical poetry on homoerotic themes, and wrote poems drawing on ancient Greek imagery and language such as ''Eudiades'', which has been called "the most famous of his homoerotic poems": "The metaphors are Greek, the tone Arcadian and the emotions a bit sentimental for present-day readers."

One of the ways in which Symonds and Whitman expressed themselves in their correspondence on the subject of homosexuality was through references to ancient Greek culture, such as the intimate friendship between Callicrates

Callicrates or Kallikrates (; el, Καλλικράτης ) was an ancient Greek architect active in the middle of the fifth century BC. He and Ictinus were architects of the Parthenon (Plutarch, ''Pericles'', 13). An inscription identifies him ...

, "the most beautiful man among the Spartans", and the soldier Aristodemus

In Greek mythology, Aristodemus (Ancient Greek: Ἀριστόδημος) was one of the Heracleidae, son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Temenus. He was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final attac ...

. Symonds was influenced by Karl Otfried Müller's work on the Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ionian ...

, which included an "unembarrassed" examination of the place of pederasty in Spartan pedagogy, military life, and society. Symonds distinguished between "heroic love", for which the ideal friendship of Achilles and Patroclus

The relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is a key element of the stories associated with the Trojan War. Its exact nature—whether homosexual, a non-sexual deep friendship, or something else entirely—has been a subject of dispute in bot ...

served as a model, and "Greek love", which combined social ideals with "vulgar" reality. Symonds envisioned a "nationalist homosexuality" based on the model of Greek love, distanced from effeminacy and "debasing" behaviors and viewed as "in its origin and essence, military". He tried to reconcile his presentation of Greek love with Christian and chivalrous values. His strategy for influencing social acceptance of homosexuality and legal reform in England included evoking an idealized Greek model that reflected Victorian moral values such as honor, devotion, and self-sacrifice.

The trial of Oscar Wilde

During his relationship with Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, Wilde frequently invoked the historical precedent of Greek models of love and masculinity, calling Douglas the contemporary "Hyacinthus, whom Apollo loved so madly," in a letter to him in July 1893. The trial of Oscar Wilde marked the end of the period when proponents of "Greek love" could hope to legitimate homosexuality by appeals to a classical model. During the cross examination, Wilde defended his statement that "pleasure is the only thing one should live for," by acknowledging: "I am, on that point, entirely on the side of the ancients—the Greeks. It is a pagan idea." With the rise of sexology, however, that kind of defense failed to hold.20th and 21st centuries

The legacy of Greece in homosexual aesthetics became problematic, and the meaning of a "costume" derived from classical antiquity was questioned. The French theorist Michel Foucault (1926–1984), perhaps best known for his work ''The History of Sexuality

''The History of Sexuality'' (french: L'Histoire de la sexualité) is a four-volume study of sexuality in the Western world by the French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault, in which the author examines the emergence of "sexuality" as a di ...

'', rejected essentialist

Essentialism is the view that objects have a set of attributes that are necessary to their identity. In early Western thought, Plato's idealism held that all things have such an "essence"—an "idea" or "form". In ''Categories'', Aristotle si ...

conceptions of gay history, and fostered a now "widely accepted" view that "Greek love is not a prefiguration of modern homosexuality."Eriobon, Didier. ''Insult and the Making of the Gay Self'', translated by Michael Lucey (Duke University Press, 2004)

See also

*Catamite

In ancient Greece and Rome, a catamite (Latin: ''catamitus'') was a pubescent boy who was the intimate companion of an older male, usually in a pederastic relationship. It was generally a term of affection and literally means " Ganymede" in ...

* Diotima of Mantinea

Diotima of Mantinea (; el, Διοτίμα; la, Diotīma) is the name or pseudonym of an ancient Greek character in Plato's dialogue ''Symposium'', possibly an actual historical figure, indicated as having lived circa 440 B.C. Her ideas and doct ...

* Eros

In Greek mythology, Eros (, ; grc, Ἔρως, Érōs, Love, Desire) is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid ("desire").''Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia'', The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215. In the ear ...

*''The Four Loves

''The Four Loves'' is a 1960 book by C. S. Lewis which explores the nature of love from a Christian and philosophical perspective through thought experiments. The book was based on a set of radio talks from 1958 which had been criticised in the ...

'' by C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

* Greek words for love

* History of erotic depictions

The history of erotic depictions includes paintings, sculpture, photographs, dramatic arts, music and writings that show scenes of a sexual nature throughout time. They have been created by nearly every civilization, ancient and modern. Early ...

* Homosexuality in Ancient Greece

In classical antiquity, writers such as Herodotus, Plato, Xenophon, Athenaeus and many others explored aspects of homosexuality in Greek society. The most widespread and socially significant form of same-sex sexual relations in ancient Greece amo ...

* Homosexuality in Ancient Rome

Homosexuality in ancient Rome often differs markedly from the contemporary West. Latin lacks words that would precisely translate "homosexual" and "heterosexual". The primary dichotomy of ancient Roman sexuality was active/ dominant/masculine ...

* Intellectual virtue

Intellectual virtues are qualities of mind and character that promote intellectual flourishing, critical thinking, and the pursuit of truth. They include: intellectual responsibility, perseverance, open-mindedness, empathy, integrity, intellect ...

– Greek words for knowledge

* Pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and an ...

* Pederasty in ancient Greece

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged romantic relationship between an older male (the ''erastes'') and a younger male (the '' eromenos'') usually in his teens. It was characteristic of the Archaic and Classical periods. The i ...

* Sapphic love

Terms used to describe homosexuality have gone through many changes since the emergence of the first terms in the mid-19th century. In English, some terms in widespread use have been sodomite, Achillean, Sapphic, Uranian, homophile, lesbian, ...

* Uranian poetry

The Uranians were a 19th-century clandestine group of up to several dozen male homosexual poets and prose writers who principally wrote on the subject of the love of (or by) adolescent boys. In a strict definition they were an English literary a ...

References

Sources

* * *Bibliography

*Blanshard, Alastair J. L. (2004) "Greek Love," essay at p. 161 of Eriobon, Didier ''Insult and the Making of the Gay Self'', transl. Lucey M. (Duke University Press). * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Greek love Philosophy of love Philosophy of sexuality LGBT and society Same-sex sexuality Sexuality in classical antiquity Sexuality in ancient Rome LGBT literature LGBT terminology LGBT themes in mythology LGBT themes in Greek mythology Gay history LGBT history in the United Kingdom Euphemisms Sexuality in ancient Greece LGBT history in Greece Cultural depictions of ancient Greek people Ancient Greece in art and culture