Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the

An earlier, influential concept was the geographically smaller version of the co-prosperity sphere which was called , which was announced by

An earlier, influential concept was the geographically smaller version of the co-prosperity sphere which was called , which was announced by

The took place in Tokyo on 5–6 November 1943: Japan hosted the

The took place in Tokyo on 5–6 November 1943: Japan hosted the

The failure of Japan to understand the goals and interests of the other countries involved in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere led to a weak association of countries bound to Japan only in theory and not in spirit. Dr. Ba Maw argues that Japan could have engineered a very different outcome if the Japanese had only managed to act in accord with the declared aims of "Asia for the Asiatics". He argues that if Japan had proclaimed this maxim at the beginning of the war, and if the Japanese had actually acted on that idea,

The failure of Japan to understand the goals and interests of the other countries involved in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere led to a weak association of countries bound to Japan only in theory and not in spirit. Dr. Ba Maw argues that Japan could have engineered a very different outcome if the Japanese had only managed to act in accord with the declared aims of "Asia for the Asiatics". He argues that if Japan had proclaimed this maxim at the beginning of the war, and if the Japanese had actually acted on that idea,

In Thailand, a street was built to demonstrate it, to be filled with modern buildings and shops, but of it consisted of false fronts. A network of Japanese-sponsored film production, distribution, and exhibition companies extended across the Japanese Empire and was collectively referred to as the Greater East Asian Film Sphere. These film centers mass-produced shorts, newsreels, and feature films to encourage Japanese language acquisition as well as cooperation with Japanese colonial authorities.

Prior to the escalation of World War II to the Pacific and East Asia, the Japanese planners regarded it as self-evident that the conquests secured in Japan's earlier wars with

Prior to the escalation of World War II to the Pacific and East Asia, the Japanese planners regarded it as self-evident that the conquests secured in Japan's earlier wars with

Parts of the plan depended on successful negotiations with Nazi Germany and a global victory by the Axis powers. After Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, Japan presented the Germans with a drafted military convention that would specifically delimit the Asian continent by a dividing line along the

Parts of the plan depended on successful negotiations with Nazi Germany and a global victory by the Axis powers. After Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, Japan presented the Germans with a drafted military convention that would specifically delimit the Asian continent by a dividing line along the

''War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War.''

New York:

"The Expansion of Japan: A Study in Oriental Geopolitics: Part II. The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere." ''The Geographical Journal'' (1950): 179–193.

* *Iriye, Akira. (1999)

''Pearl Harbor and the coming of the Pacific War :a Brief History with Documents and Essays.''

Boston: St. Martin's Press. ; * Lebra, Joyce C. (ed.) (1975)

''Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents.''

Oxford:

''The Pacific War:Japan versus the allies''

(Greenwood Publishing Group, ) *Myers, Ramon Hawley and Mark R. Peattie. (1984

''The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945.''

Princeton:

"The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945,"

i

''The Cambridge History of Japan: the Twentieth Century''

(editor, Peter Duus). Cambridge:

in JSTOR

"Japan's Intentions for Its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere as Indicated in Its Policy Plans for Thailand" ''Journal of Southeast Asian Studies'' 27#1 (1996) pp. 139–149 * * * * Ugaki, Matome. (1991)

''Fading Victory: The Diary of Ugaki Matome, 1941-1945.''

Pittsburgh:

''The 'money doctors' from Japan: finance, imperialism, and the building of the Yen Bloc, 1894–1937''

(abstract). FRIS/Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2007–2010. *Yellen, Jeremy A. (2019)

The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: When Total Empire Met Total War.

Ithaca:

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

at Britannica

Foreign Office Files for Japan and the Far EastWW2DB: Greater East Asia Conference

{{Authority control Axis powers British Malaya in World War II China in World War II Hong Kong in World War II Indonesia in World War II Japan in World War II Japanese colonial empire Japanese military occupations Japanese nationalism Manchukuo Military history of Japan during World War II Pan-Asianism Papua New Guinea in World War II Philippines in World War II Politics of World War II Shōwa Statism South Seas Mandate in World War II Spheres of influence Taiwan in World War II Thailand in World War II Vietnam in World War II

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

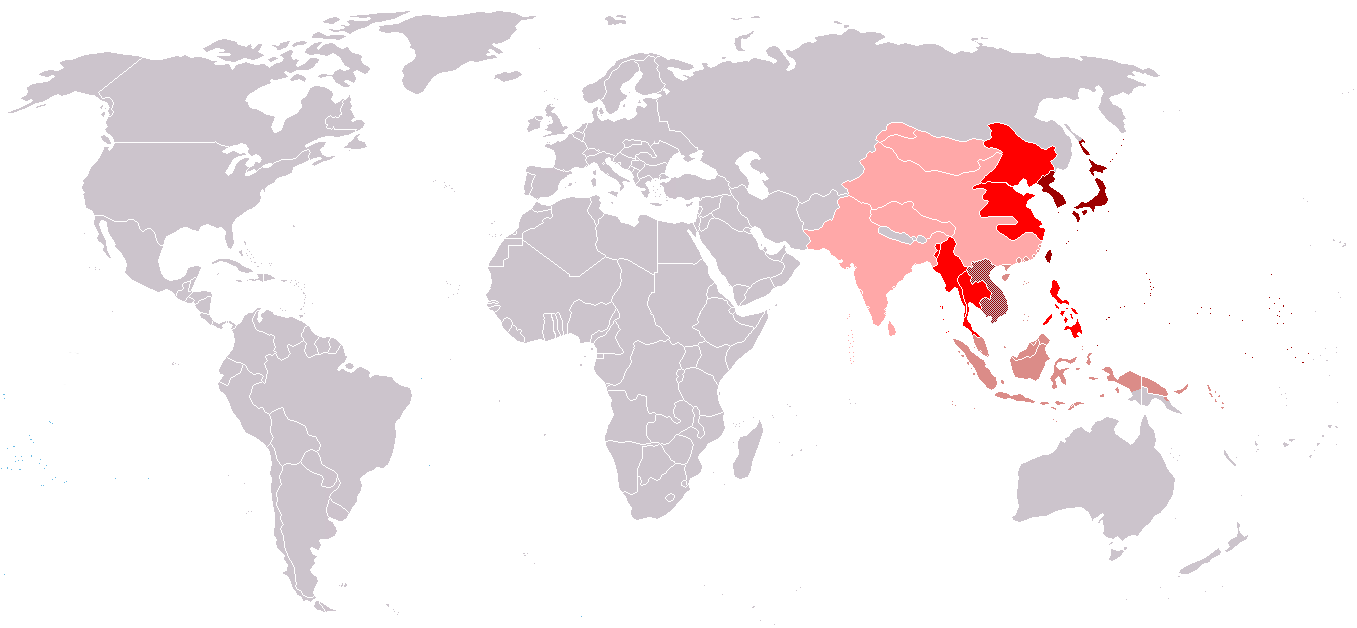

and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peoples and states that would be led by the Japanese and be free from the rule of Western powers. The idea was first announced on 1 August 1940 in a radio address delivered by Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

Yōsuke Matsuoka.

The intent and practical implementation of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere varied widely depending on the group and government department involved. Policy theorists who conceived it, as well as the vast majority of the Japanese population at large, saw it for its pan-Asian ideals of freedom and independence from Western colonial rule. In practice, however, it was frequently used by militarists and nationalists, who saw an effective policy vehicle through which to strengthen Japan's position and advance its dominance within Asia. The latter approach was reflected in a document released by Japan's Ministry of Health and Welfare, ''An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus

was a secret Japanese government report created by the Ministry of Health and Welfare's Institute of Population Problems (now the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research), and completed on July 1, 1943.

The document, co ...

'', which laid out the central position of Japan within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, and promoted the idea of Japanese superiority over other Asians. Japanese spokesmen openly described the Great East Asia Co-Prosperity as a device for the "development of the Japanese race." When World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

ended, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere became a source of criticism and scorn.

Development of the concept

An earlier, influential concept was the geographically smaller version of the co-prosperity sphere which was called , which was announced by

An earlier, influential concept was the geographically smaller version of the co-prosperity sphere which was called , which was announced by Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

on 3 November 1938 and was limited to East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

only.

The original concept was an idealistic wish to liberate Asia from the rule of European colonial powers. However, some Japanese nationalists believed it could be used to gain resources which would be used to ensure that Japan would continue to be a modern power, and militarists believed that resource-rich Western colonies contained abundant supplies of raw materials which could be used to wage wars. Many Japanese nationalists were drawn to it as an ideal. Many of them remained convinced throughout the war that the Sphere was idealistic, offering slogans in a newspaper competition praising the sphere for constructive efforts and peace.

Prior to the invasion of Southeast Asia, Konoe planned the Sphere in 1940 in an attempt to create a Great East Asia, comprising Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, and parts of Southeast Asia, that would, according to imperial propaganda, establish a new international order seeking "co-prosperity" for Asian countries which would share prosperity and peace, free from Western colonialism and domination of the White man.Iriye, Akira. (1999). ''Pearl Harbor and the coming of the Pacific War: a Brief History with Documents and Essays'', p. 6. Military goals of this expansion included naval operations in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

and the isolation of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. This would enable the principle of hakkō ichiu.James L. McClain, ''Japan: A Modern History'' p 470

This was just one of a number of slogans and concepts which were used to justify Japanese aggression in East Asia from the 1930s through the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The term "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" is largely remembered by Western scholars as a front for the Japanese control of occupied countries during World War II, in which puppet governments manipulated local populations and economies for the benefit of Imperial Japan.

To combat the protectionist dollar and sterling zones, Japanese economic planners called for a "yen bloc".

Japan's experiment with such financial imperialism encompassed both official and semi-official colonies. In the period between 1895 (when Japan annexed Taiwan) and 1937 (the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

), monetary specialists in Tokyo directed and managed programs of coordinated monetary reforms in Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, and the peripheral Japanese-controlled islands in the Pacific. These reforms aimed to foster a network of linked political and economic relationships. These efforts foundered in the eventual debacle of the Greater East-Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

History

The concept of a unified East Asia was developed by Hachirō Arita, who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1936 to 1940. The Japanese Army said that the new Japanese empire was the Asian equivalent of the Monroe Doctrine, especially with the Roosevelt Corollary. The regions of Asia, it was argued, were as essential to Japan as Latin America was to the United States. The JapaneseForeign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

Yōsuke Matsuoka formally announced the idea of the Co-Prosperity Sphere on 1 August 1940, in a press interview, but it had existed in other forms for many years. Leaders in Japan had long had an interest in the idea. The outbreak of World War II fighting in Europe had given the Japanese an opportunity to demand the withdrawal of support from China in the name of "Asia for Asiatics", with the European powers unable to effectively retaliate. Many of the other countries within the boundaries of the sphere were under colonial rule and elements of their population were sympathetic to Japan (as in the case of Indonesia), occupied by Japan in the early phases of the war and reformed under puppet governments, or already under Japan's control at the outset (as in the case of Manchukuo). These factors helped make the formation of the sphere, while lacking any real authority or joint power, come together without much difficulty.

After Japan's advancements into French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

in 1940, knowing that Japan was completely dependent on other countries for natural resources, President Roosevelt ordered a trade embargo on steel and oil, raw materials that were vital to Japan's war effort. Without steel and oil imports, Japan's military could not fight for long. As a result of the embargo, Japan decided to attack the British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia, seizing the raw materials needed for the war effort. On 1 August 1940, Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yōsuke announced the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere; on 7 December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor; and on 19 December 1941, after the Japanese invasions of the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

, in a radio broadcast Japanese politician Kishi Nobusuke

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Sh� ...

announced the vast resources available for Japanese use in the newly conquered territories.

As part of its war drive, Japanese propaganda included phrases like "Asia for the Asiatics!" and talked about the need to liberate Asian colonies from the control of Western powers.Anthony Rhodes, ''Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II'', p. 248, 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York The Japanese failure to bring the ongoing Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

to a swift conclusion was blamed in part on the lack of resources; Japanese propaganda claimed this was due to the refusal by Western powers to supply Japan's military. Although invading Japanese forces sometimes received rapturous welcomes throughout Western colonies in Asia that they had recently captured, the subsequent brutality of the Japanese military led many of the inhabitants of those regions to regard Japan as being worse than their former colonial rulers. The Japanese government directed that economies of occupied territories be managed strictly for the production of raw materials for the Japanese war effort; a cabinet member declared, "There are no restrictions. They are enemy possessions. We can take them, do anything we want". For example, according to estimates, under Japanese occupation, about 100,000 Burmese and Malay Indian laborers died while constructing the Burma-Siam Railway

The Burma Railway, also known as the Siam–Burma Railway, Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, or as the Death Railway, is a railway between Ban Pong, Thailand and Thanbyuzayat, Burma (now called Myanmar). It was built from 1940 to 1943 ...

.

''An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus

was a secret Japanese government report created by the Ministry of Health and Welfare's Institute of Population Problems (now the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research), and completed on July 1, 1943.

The document, co ...

'' – a secret document completed in 1943 for high-ranking government use – laid out that Japan, as the originators and strongest military power within the region, would naturally take the superior position within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, with the other nations under Japan's umbrella of protection.

The booklet ''Read This and the War is Won''—for the Japanese army—presented colonialism as an oppressive group of colonists living in luxury by burdening Asians. According to Japan, since racial ties of blood connected other Asians to the Japanese, and Asians had been weakened by colonialism, it was Japan's self-appointed role to "make men of them again" and liberate them from their Western oppressors.

According to Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō (in office 1941–1942 and 1945), should Japan be successful in creating this sphere, it would emerge as the leader of Eastern Asia, and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere would be synonymous with the Japanese Empire.

Greater East Asia Conference

heads of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

of various component members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The conference was also referred to as the ''Tokyo Conference''. The common language used by the delegates during the conference was English. The conference was mainly used as propaganda.

At the conference Tojo greeted them with a speech praising the "spiritual essence" of Asia, as opposed to the "materialistic civilization" of the West. Their meeting was characterized by praise of solidarity and condemnation of Western colonialism but without practical plans for either economic development or integration. Because of a lack of military representatives at the conference, the conference served little military value.

With the simultaneous use of Wilsonian

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and p ...

and Pan-Asianism rhetoric, the goals of the conference were to solidify the commitment of certain Asian countries to Japan's war effort and to improve Japan's world image; however, the representatives of the other attending countries were neither independent nor treated as equals by Japan, and as a result, Asian countries were violently used to achieve Japan's imperialist ambitions.

The following dignitaries attended:

*Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

, Prime Minister of the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

* Zhang Jinghui, Prime Minister of the Empire of Manchuria

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese in ...

* Wang Jingwei, President of the Republic of China (Nanjing)

*Ba Maw

Ba Maw ( my, ဘမော်, ; 8 February 1893 – 29 May 1977) was a Burmese lawyer and political leader, active during the interwar and World War II periods. Dr. Ba Maw is a descendant of the Mon Dynasty. He was the first Burma Premier ...

, Head of State of the State of Burma

*Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose ( ; 23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*) was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperi ...

, Head of State of the Provisional Government of Free India

The Provisional Government of Free India (''Ārzī Hukūmat-e-Āzād Hind'') or, more simply, ''Azad Hind'', was an Indian provisional government established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II. It was created in October 1943 ...

*José P. Laurel

José Paciano Laurel y García (; March 9, 1891 – November 6, 1959) was a Filipino politician, lawyer, and judge, who served as the president of the Japanese-occupied Second Philippine Republic, a puppet state during World War II, from 194 ...

, President of the Republic of the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

*Prince Wan Waithayakon

Wan Waithayakon (full title: His Royal Highness Prince Vanna Vaidhayakara, the Prince Naradhip Bongsprabandh), known in the West as ''Wan Waithayakon'' (1891–1976), was a Thai royal prince and diplomat. He was President of the Eleventh Session ...

, envoy from the Kingdom of Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

Members of the Sphere

Member countries and the year in which they joined the sphere: * (30 November 1940) * (30 November 1940) * Republic of China (Nanjing) (30 November 1940) * (21 December 1941) * State of Burma (1 August 1943) * (14 October 1943) *Provisional Government of Free India

The Provisional Government of Free India (''Ārzī Hukūmat-e-Āzād Hind'') or, more simply, ''Azad Hind'', was an Indian provisional government established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II. It was created in October 1943 ...

(21 October 1943)

* Kingdom of Kampuchea (9 March 1945)

* Empire of Vietnam

The Empire of Vietnam (; Literary Chinese and Contemporary Japanese: ; Modern Japanese: ja, ベトナム帝国, Betonamu Teikoku, label=none) was a short-lived puppet state of Imperial Japan governing the former French protectorates of Ann ...

(11 March 1945)

* Kingdom of Luang Phrabang (8 April 1945)

Imperial rule

The ideology of theJapanese colonial empire

The territorial conquests of the Empire of Japan in the Western Pacific and East Asia regions began in 1895 with its victory over Qing China in the First Sino-Japanese War. Subsequent victories over the Russian Empire (Russo-Japanese War) and Ge ...

, as it expanded dramatically during the war, contained two contradictory impulses. On the one hand, it preached the unity of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a coalition of Asian races, directed by Japan, against Western imperialism in Asia. This approach celebrated the spiritual values of the East in opposition to the "crass materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

" of the West. In practice, however, the Japanese installed organizationally-minded bureaucrats and engineers to run their new empire, and they believed in ideals of efficiency, modernization, and engineering solutions to social problems. Japanese was the official language of the bureaucracy in all of the areas and was taught at schools as a national language.

Japan set up puppet regimes in Manchuria and China; they vanished at the end of the war. The Imperial Army operated ruthless administrations in most of the conquered areas, but paid more favorable attention to the Dutch East Indies. The main goal was to obtain oil. The Dutch colonial government destroyed the oil wells, however, the Japanese were able to repair and reopen them within a few months of their conquest. However most of the tankers transporting oil to Japan were sunk by U.S. Navy submarines, so Japan's oil shortage became increasingly acute. Japan sponsored an Indonesian nationalist movement under Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

. Sukarno finally came to power in the late 1940s after several years of battling the Dutch.

Philippines

With a view of building up the economic base of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, the Japanese Army envisioned using the Philippine islands as a source of agricultural products needed by its industry. For example, Japan had a surplus of sugar from Taiwan, and a severe shortage ofcotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

, so they tried to grow cotton on sugar lands with disastrous results. They lacked the seeds, pesticides, and technical skills to grow cotton. Jobless farm workers flocked to the cities, where there was minimal relief and few jobs. The Japanese Army also tried using cane sugar for fuel, castor beans and copra

Copra (from ) is the dried, white flesh of the coconut from which coconut oil is extracted. Traditionally, the coconuts are sun-dried, especially for export, before the oil, also known as copra oil, is pressed out. The oil extracted from co ...

for oil, '' Derris'' for quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, cotton for uniforms, and abacá for rope. The plans were very difficult to implement in the face of limited skills, collapsed international markets, bad weather, and transportation shortages. The program was a failure that gave very little help to Japanese industry, and diverted resources needed for food production. As Karnow reports, Filipinos "rapidly learned as well that 'co-prosperity' meant servitude to Japan's economic requirements".

Living conditions were bad throughout the Philippines during the war. Transportation between the islands was difficult because of a lack of fuel. Food was in very short supply, with sporadic famines and epidemic diseases that killed hundreds of thousands of people. In October 1943, Japan declared the Philippines an independent republic. The Japanese-sponsored Second Philippine Republic headed by President José P. Laurel

José Paciano Laurel y García (; March 9, 1891 – November 6, 1959) was a Filipino politician, lawyer, and judge, who served as the president of the Japanese-occupied Second Philippine Republic, a puppet state during World War II, from 194 ...

proved to be ineffective and unpopular as Japan maintained very tight controls.

Failure

The Co-Prosperity Sphere collapsed with Japan's surrender to the Allies in September 1945. Dr.Ba Maw

Ba Maw ( my, ဘမော်, ; 8 February 1893 – 29 May 1977) was a Burmese lawyer and political leader, active during the interwar and World War II periods. Dr. Ba Maw is a descendant of the Mon Dynasty. He was the first Burma Premier ...

, wartime President of Burma under the Japanese, blamed the Japanese military:

In other words, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere operated not for the betterment of all the Asian countries, but rather for Japan's own interests, and thus the Japanese failed to gather support in other Asian countries. Nationalist movements did appear in these Asian countries during this period and these nationalists did, to some extent, cooperate with the Japanese. However, Willard Elsbree, professor emeritus of political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and ...

at Ohio University

Ohio University is a public research university in Athens, Ohio. The first university chartered by an Act of Congress and the first to be chartered in Ohio, the university was chartered in 1787 by the Congress of the Confederation and subse ...

, claims that the Japanese government and these nationalist leaders never developed "a real unity of interests between the two parties, ndthere was no overwhelming despair on the part of the Asians at Japan's defeat".

Propaganda efforts

Pamphlets were dropped by airplane on the Philippines, Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, Singapore, and Indonesia, urging them to join this movement. Mutual cultural societies were founded in all conquered lands to ingratiate with the natives and try to supplant English with Japanese as the commonly used language. Multi-lingual pamphlets depicted many Asians marching or working together in happy unity, with the flags of all the states and a map depicting the intended sphere. Others proclaimed that they had given independent governments to the countries they occupied, a claim undermined by the lack of power given these puppet governments.JAPANESE PSYOP DURING WWIIIn Thailand, a street was built to demonstrate it, to be filled with modern buildings and shops, but of it consisted of false fronts. A network of Japanese-sponsored film production, distribution, and exhibition companies extended across the Japanese Empire and was collectively referred to as the Greater East Asian Film Sphere. These film centers mass-produced shorts, newsreels, and feature films to encourage Japanese language acquisition as well as cooperation with Japanese colonial authorities.

Projected territorial extent

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

(South Sakhalin

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

and Kwantung), Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

(South Seas Mandate

The South Seas Mandate, officially the Mandate for the German Possessions in the Pacific Ocean Lying North of the Equator, was a League of Nations mandate in the " South Seas" given to the Empire of Japan by the League of Nations following W ...

) and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

(Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

) would be retained, as well as Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

(''Chōsen''), Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

(''Formosa''), the recently seized additional portions of China and occupied French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

.Weinberg, L. Gerhard. (2005). ''Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders'' p.62-65.

The Land Disposal Plan

A reasonably accurate indication as to the geographic dimensions of the Co-Prosperity Sphere are elaborated on in a Japanese wartime document prepared in December 1941 by the Research Department of the Imperial Ministry of War. Known as the "Land Disposal Plan in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" () it was put together with the consent of and according to the directions of the Minister of War (later Prime Minister) Hideki Tōjō. It assumed that the already established puppet governments ofManchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

, Mengjiang, and the Wang Jingwei regime

The Wang Jingwei regime or the Wang Ching-wei regime is the common name of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China ( zh , t = 中華民國國民政府 , p = Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guómín Zhèngfǔ ), the government of the pu ...

in Japanese-occupied China would continue to function in these areas. Beyond these contemporary parts of Japan's sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

it also envisaged the conquest of a vast range of territories covering virtually all of East Asia, the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

, and even sizable portions of the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the te ...

, including in locations as far removed from Japan as South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

and the eastern Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

.

Although the projected extension of the Co-Prosperity Sphere was extremely ambitious, the Japanese goal during the "Greater East Asia War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

" was not to acquire all the territory designated in the plan at once, but to prepare for a future decisive war some 20 years later by conquering the Asian colonies of the defeated European powers, as well as the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. When Tōjō spoke on the plan to the House of Peers he was vague about the long-term prospects, but insinuated that the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

might be allowed independence, although vital territories such as Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

would remain under Japanese rule.W. G. Beasley, ''The Rise of Modern Japan'', p 204

The Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, ...

n islands that had been seized from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and which were assigned to Japan as C-Class Mandates, namely the Marianas

The Mariana Islands (; also the Marianas; in Chamorro: ''Manislan Mariånas'') are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, betw ...

, Carolines, Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Inte ...

, and several others do not figure in this project. They were the subject of earlier negotiations with the Germans and were expected to be officially ceded to Japan in return for economic and monetary compensations.

The plan divided Japan's future empire into two different groups. The first group of territories were expected to become either part of Japan or otherwise be under its direct administration. Second were those territories that would fall under the control of a number of tightly controlled pro-Japanese vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back t ...

s based on the model of Manchukuo, as nominally "independent" members of the Greater East Asian alliance.

Parts of the plan depended on successful negotiations with Nazi Germany and a global victory by the Axis powers. After Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, Japan presented the Germans with a drafted military convention that would specifically delimit the Asian continent by a dividing line along the

Parts of the plan depended on successful negotiations with Nazi Germany and a global victory by the Axis powers. After Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, Japan presented the Germans with a drafted military convention that would specifically delimit the Asian continent by a dividing line along the 70th meridian east

The meridian 70° east of Prime Meridian, Greenwich is a line of longitude that extends from the North Pole across the Arctic Ocean, Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and Antarctica to the South Pole.

The 70th meridian east forms a gr ...

longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

. This line, running southwards through the Ob River

}

The Ob ( rus, Обь, p=opʲ: Ob') is a major river in Russia. It is in western Siberia; and together with Irtysh forms the world's seventh-longest river system, at . It forms at the confluence of the Biya and Katun which have their origins ...

's Arctic estuary, southwards to just east of Khost

Khōst ( ps, خوست) is the capital of Khost Province in Afghanistan. It is the largest city in the southeastern part of the country, and also the largest in the region of Loya Paktia. To the south and east of Khost lie Waziristan and Kurram ...

in Afghanistan and heading into the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

just west of Rajkot

Rajkot () is the fourth-largest city in the Indian state of Gujarat after Ahmedabad, Vadodara, and Surat, and is in the centre of the Saurashtra region of Gujarat. Rajkot is the 35th-largest metropolitan area in India, with a population ...

in India, would have split Germany's ''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

'' and Italy's '' spazio vitale'' territories to the west of it, and Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and its other areas to the east of it. The plan of the Third Reich for fortifying its own ''Lebensraum'' territory's eastern limits, beyond which the Co-Prosperity Sphere's northwestern frontier areas would exist in East Asia, involved the creation of a "living wall" of '' Wehrbauer'' "soldier-peasant" communities defending it. However, it is unknown if the Axis powers ever formally negotiated a possible, complementary ''second'' demarcation line that would have divided the Western Hemisphere.

Japanese-governed

*''Government-General of Formosa'' :Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Portuguese Macau

Portuguese Macau (officially the Province of Macau until 1976, and then the Autonomous Region of Macau from 1976 to 1999) was a Portuguese colony that existed from the first official Portuguese settlement in 1557 to the end of colonial rul ...

(to be purchased from Portugal), the Paracel Islands, and Hainan Island

Hainan (, ; ) is the smallest and southernmost province of the People's Republic of China (PRC), consisting of various islands in the South China Sea. , the largest and most populous island in China,The island of Taiwan, which is slight ...

(to be purchased from the Chinese puppet regime). Contrary to its name it was not intended to include the island of Formosa (Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

).

*''South Seas Government Office''

:Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, Nauru

Nauru ( or ; na, Naoero), officially the Republic of Nauru ( na, Repubrikin Naoero) and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Oceania, in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in ...

, Ocean Island, the Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands ( gil, Tungaru;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this n ...

and Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of T ...

.

*''Melanesian Region Government-General'' or ''South Pacific Government-General''

:British New Guinea, Australian New Guinea, the Admiralties

The Admiralty Islands are an archipelago group of 18 islands in the Bismarck Archipelago, to the north of New Guinea in the South Pacific Ocean. These are also sometimes called the Manus Islands, after the largest island.

These rainforest-cov ...

, New Britain

New Britain ( tpi, Niu Briten) is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi the D ...

, New Ireland, the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

, the Santa Cruz Archipelago, the Ellice Islands, the Fiji Islands

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

, the New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides, Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the isla ...

, New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

, the Loyalty Islands, and the Chesterfield Islands.

*''Eastern Pacific Government-General''

: Hawaii Territory, Howland Island

Howland Island () is an uninhabited coral island located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean, about southwest of Honolulu. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii and Australia and is an unorganized, unincorporated ter ...

, Baker Island

Baker Island, formerly known as New Nantucket, is an uninhabited atoll just north of the Equator in the central Pacific Ocean about southwest of Honolulu. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbor is H ...

, the Phoenix Islands

The Phoenix Islands, or Rawaki, are a group of eight atolls and two submerged coral reefs that lie east of the Gilbert Islands and west of the Line Islands in the central Pacific Ocean, north of Samoa. They are part of the Republic of Kiri ...

, the Rain Islands, the Marquesas

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in t ...

and Tuamotu Islands, the Society Islands

The Society Islands (french: Îles de la Société, officially ''Archipel de la Société;'' ty, Tōtaiete mā) are an archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the F ...

, the Cook

Cook or The Cook may refer to:

Food preparation

* Cooking, the preparation of food

* Cook (domestic worker), a household staff member who prepares food

* Cook (professional), an individual who prepares food for consumption in the food industry

* ...

and Austral Islands

The Austral Islands (french: Îles Australes, officially ''Archipel des Australes;'' ty, Tuha'a Pae) are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of the French Republic in the South Pacific. Geographically, t ...

, all of the Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands ( sm, Motu o Sāmoa) are an archipelago covering in the central South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Independent State of Samoa an ...

and Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

. The possibility of re-establishing the defunct Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent islan ...

was also considered, based on the model of Manchukuo.Levine (1995), p. 92 Those favoring annexation of Hawaii (on the model of Karafuto) intended to use the local Japanese community, which had constituted 43% (c. 160,000) of Hawaii's population in the 1920s, as a leverage. Hawaii was to become self-sufficient in food production, while the Big Five corporations of sugar and pineapple processing were to be broken up. No decision was ever reached regarding whether Hawaii would be annexed to Japan, become a puppet kingdom, or be used as a bargaining chip for leverage against the US.

*''Australian Government-General''

:All of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

including Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. Australia and New Zealand were to accommodate up to two million Japanese settlers. However, there are indications that the Japanese were also looking for a separate peace with Australia, and a satellite rather than colony status similar to that of Burma and the Philippines.

*''New Zealand Government-General''

:The New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

and South Island

The South Island, also officially named , is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand in surface area, the other being the smaller but more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman ...

s, Macquarie Island, as well as the rest of the Southwest Pacific.

*''Ceylon Government-General''

:All of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

below a line running approximately from Portuguese Goa to the coastline of the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line bet ...

.

*''Alaska Government-General''

:The Alaska Territory

The Territory of Alaska or Alaska Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from August 24, 1912, until Alaska was granted statehood on January 3, 1959. The territory was previously Russian America, 1784–1867; th ...

, the Yukon Territory

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

, the western portion of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

, Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest T ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

, and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. There were also plans to make the American West Coast (comprising California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

) a semi-autonomous satellite state. This latter plan was not seriously considered; it depended upon a global victory of Axis forces.

*''Government-General of Central America''

:Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by Hon ...

, El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south ...

, Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

, British Honduras

British Honduras was a British Crown colony on the east coast of Central America, south of Mexico, from 1783 to 1964, then a self-governing colony, renamed Belize in June 1973,

, Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the coun ...

, Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

, Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

, Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the ...

, the Maracaibo

)

, motto = "''Muy noble y leal''"(English: "Very noble and loyal")

, anthem =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_alt = ...

(western) portion of Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

, Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, and the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

. In addition, if either Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

or Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

were to enter the war against Japan, substantial parts of these states would also be ceded to Japan. Events that transpired between May 22, 1942, when Mexico declared war on the Axis, through Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

's declaration of war on February 12, 1944, and concluding with Chile only declaring war on Japan by April 11, 1945 (as Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

was nearly defeated at that time), brought all three of these southeast Pacific Rim

The Pacific Rim comprises the lands around the rim of the Pacific Ocean. The '' Pacific Basin'' includes the Pacific Rim and the islands in the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific Rim roughly overlaps with the geologic Pacific Ring of Fire.

List of ...

nations of the Western Hemisphere's Pacific coast into conflict with Japan by the war's end. The future of Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

, British and Dutch Guiana, and the British and French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

possessions in the Leeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean Sea North Atlantic Ocean

, co ...

at the hands of Imperial Japan were meant to be left open for negotiations with Nazi Germany had the Axis forces been victorious.

Asian puppet states

*''East Indies Kingdom'' :Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

, British Borneo

British Borneo comprised the four northern parts of the island of Borneo, which are now the country of Brunei, two Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, and the Malaysian federal territory of Labuan. During the British colonial rule before Wor ...

, the Christmas Islands

Christmas Island, officially the Territory of Christmas Island, is an Australian external territory comprising the island of the same name. It is located in the Indian Ocean, around south of Java and Sumatra and around north-west of the ...

, Cocos Islands

)

, anthem = "''Advance Australia Fair''"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = Australia on the globe (Cocos (Keeling) Islands special) (Southeast Asia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

, map_caption = ...

, Andaman, Nicobar Islands

The Nicobar Islands are an archipelagic island chain in the eastern Indian Ocean. They are located in Southeast Asia, northwest of Aceh on Sumatra, and separated from Thailand to the east by the Andaman Sea. Located southeast of the Indian ...

and Portuguese Timor

Portuguese Timor ( pt, Timor Português) was a colonial possession of Portugal that existed between 1702 and 1975. During most of this period, Portugal shared the island of Timor with the Dutch East Indies.

The first Europeans to arrive in th ...

(to be purchased from Portugal).

*''Kingdom of Burma

The Konbaung dynasty ( my, ကုန်းဘောင်ခေတ်, ), also known as Third Burmese Empire (တတိယမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်) and formerly known as the Alompra dynasty (အလောင်းဘ ...

''

:Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

proper, Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

(a province of the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

) and a large part of Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

.

*''Kingdom of Malaya''

:Remainder of the Malay states

The monarchies of Malaysia refer to the constitutional monarchy system as practised in Malaysia. The political system of Malaysia is based on the Westminster parliamentary system in combination with features of a federation.

Nine of the state ...

.

*''Kingdom of Annam''

: Annam, Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist s ...

and Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain '' Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includ ...

.

*'' Kingdom of Cambodia''

:Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

and French Cochinchina.

Puppet states which already existed at the time, the Land Disposal Plan has been drafted, were:

*''Empire of Manchuria

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese in ...

''

:Chinese Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

.

*'' RNG Republic of China''

:Other parts of China occupied by Japan

*'' Mengjiang''

:Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

territories west of Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

, since 1940 officially a part of the Republic of China. It was meant as a starting point for a regime which would cover all of Mongolia.

Contrary to the plan Japan installed a puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

on the Philippines instead of exerting direct control. In the former French Indochina, the Empire of Vietnam

The Empire of Vietnam (; Literary Chinese and Contemporary Japanese: ; Modern Japanese: ja, ベトナム帝国, Betonamu Teikoku, label=none) was a short-lived puppet state of Imperial Japan governing the former French protectorates of Ann ...

, Kingdom of Kampuchea and Kingdom of Luang Phrabang were founded. The Empire of Vietnam, despite being pro-Japan, attempted to work for independence and made some progressive reforms. The State of Burma did not become a Kingdom.

Political parties and movements with Japanese support

*Azad Hind

The Provisional Government of Free India (''Ārzī Hukūmat-e-Āzād Hind'') or, more simply, ''Azad Hind'', was an Indian provisional government established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II. It was created in October 194 ...

( Indian nationalist movement)

* Indian Independence League (Indian nationalist movement)

* Indonesian Nationalist Party (Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

n nationalist movement)

* Kapisanan ng Paglilingkod sa Bagong Pilipinas (Philippine nationalist ruling party of the Second Philippine Republic)

* Kesatuan Melayu Muda (Malayan nationalist movement)

*Khmer Issarak

The Khmer Issarak ( km, ខ្មែរឥស្សរៈ, or 'Independent Khmer') was a "loosely structured" anti- French and anti-colonial independence movement. The movement has been labelled as “amorphous”. The Issarak was ...

(Cambodian-Khmer nationalist group)

*Dobama Asiayone

Dobama Asiayone ( my, တို့ဗမာအစည်းအရုံး, ''Dóbăma Ăsì-Ăyòun'', meaning ''We Burmans Association'', DAA), commonly known as the Thakhins ( my, သခင် ''sa.hkang'', lit. Lords), was a Burmese national ...

(We Burmans Association) ( Burmese nationalist association)

See also

*Axis power negotiations on the division of Asia

As the Axis powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan cemented their military alliance by mutually declaring war against the United States on December 11, 1941, the Japanese proposed a clear territorial arrangement with the two main European Axis ...

*Discrimination based on skin color

Discrimination based on skin color, also known as colorism, or shadeism, is a form of prejudice and/or discrimination in which people who share similar ethnicity traits or perceived race are treated differently based on the social implications t ...

* East Asia Development Board

* Flying geese paradigm

*Greater East Asia Conference

was an international summit held in Tokyo from 5 to 6 November 1943, in which the Empire of Japan hosted leading politicians of various component members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The event was also referred to as the Toky ...

(November 1943)

*Greater Germanic Reich

The Greater Germanic Reich (german: Großgermanisches Reich), fully styled the Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation (german: Großgermanisches Reich deutscher Nation), was the official state name of the political entity that Nazi Germany ...

* Hachirō Arita: an Army thinker who thought up the Greater East Asian concept

* Hakkō ichiu

* Ikki Kita: a Japanese nationalist who developed a similar pan-Asian concept

* Imperial Rule Assistance Association

* Japanese nationalism

* Jewish settlement in the Japanese Empire

*Latin Bloc (proposed alliance) The Latin Bloc ( it, Blocco Latino; french: Bloc Latin; es, Bloque Latino; pt, Bloco Latino; ro, Blocul Latin) was a proposal for an alliance made between the 1920s to the 1940s that began with Italy's ''Duce'' Benito Mussolini proposing such a b ...

* List of East Asian leaders in the Japanese sphere of influence (1931–1945)

* Ministry of Greater East Asia

* Monroe Doctrine

* Propaganda in Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II

* Racial Equality Proposal

*Satō Nobuhiro

was a Japanese scientist and early advocate of Japanese Westernization. He is considered the founder of the "Greater East Asia" concept.

Satō attempted to synthesize Western science (especially Astronomy) with Japanese political and philosophica ...

: the alleged developer of the Greater East Asia concept

References

Citations

Further reading

* * Dower, John W. (1986)''War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War.''

New York:

Pantheon Books

Pantheon Books is an American book publishing imprint with editorial independence. It is part of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.Random House, Inc. Datamonitor Company Profiles Authority: Retrieved 6/20/2007, from EBSCO Host Business Source ...

. ;

*Fisher, Charles A. (1950"The Expansion of Japan: A Study in Oriental Geopolitics: Part II. The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere." ''The Geographical Journal'' (1950): 179–193.

* *Iriye, Akira. (1999)

''Pearl Harbor and the coming of the Pacific War :a Brief History with Documents and Essays.''

Boston: St. Martin's Press. ; * Lebra, Joyce C. (ed.) (1975)

''Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents.''

Oxford:

Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

. ;

*Levine, Alan J. (1995)''The Pacific War:Japan versus the allies''

(Greenwood Publishing Group, ) *Myers, Ramon Hawley and Mark R. Peattie. (1984

''The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945.''

Princeton:

Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial ...

.

* Peattie, Mark R. (1988)"The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945,"

i