Great Railroad Strike of 1877 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in

American Catholic History Classroom, The Catholic University of America, accessed 20 May 2016

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 started on July 14 in

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 started on July 14 in

''Technology and Culture'' 41.3 (2000) 636-638, via Project MUSE, accessed 20 May 2016

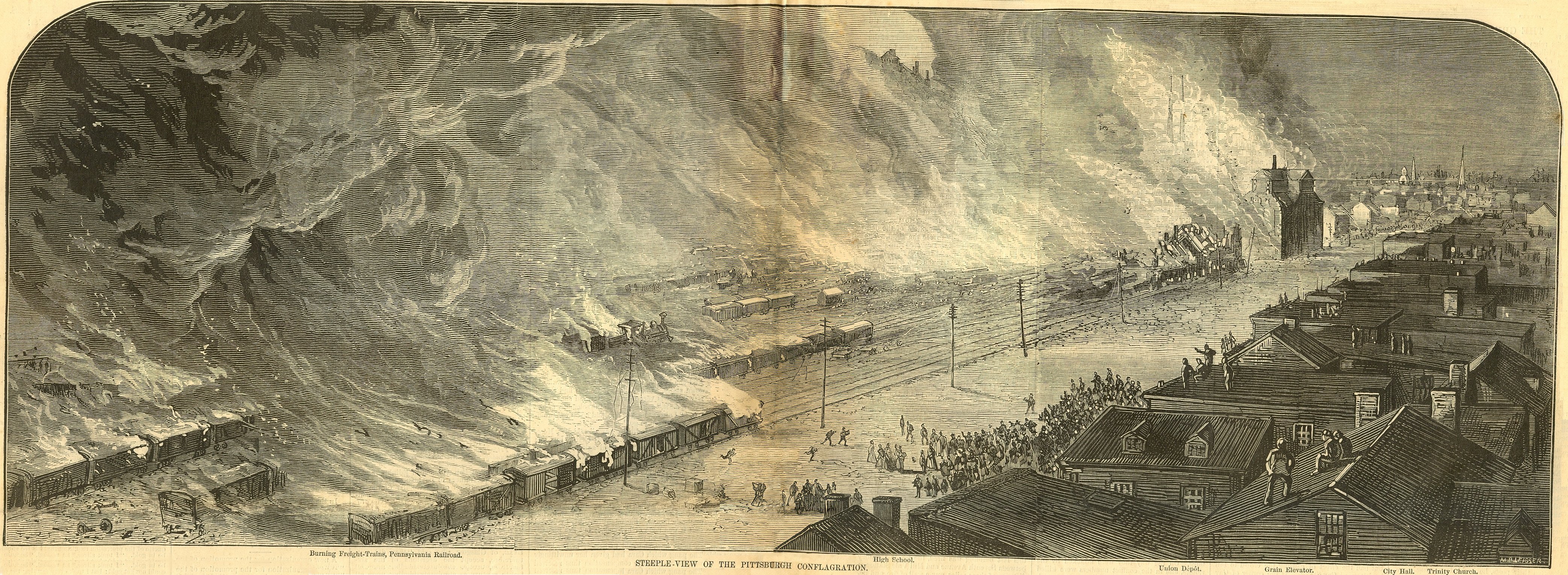

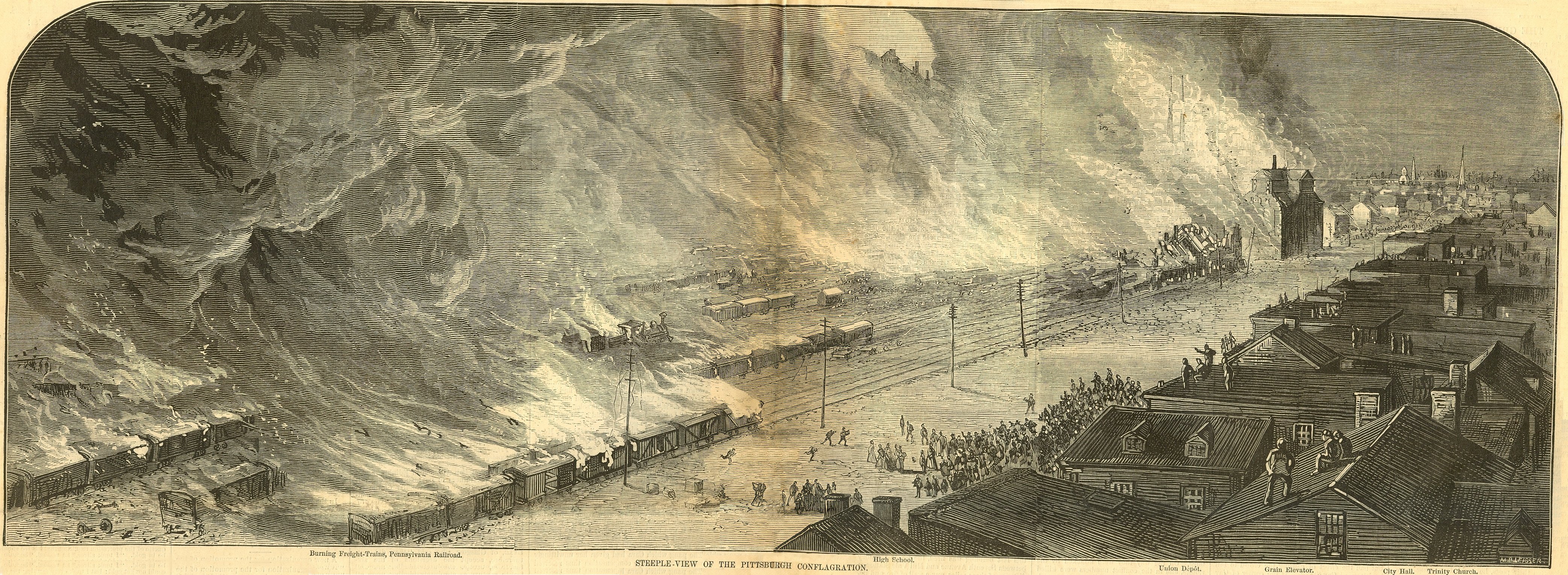

On July 21, National Guard members bayoneted and fired on rock-throwing strikers, killing 20 people and wounding 29. Rather than quell the uprising, these actions infuriated the strikers, who retaliated and forced the National Guard to take refuge in a railroad roundhouse. Strikers set fires that razed 39 buildings and destroyed rolling stock: 104 locomotives and 1,245 freight and passenger cars. On July 22, the National Guard mounted an assault on the strikers, shooting their way out of the roundhouse and killing 20 more people on their way out of the city. After more than a month of rioting and bloodshed in Pittsburgh, President

On July 21, National Guard members bayoneted and fired on rock-throwing strikers, killing 20 people and wounding 29. Rather than quell the uprising, these actions infuriated the strikers, who retaliated and forced the National Guard to take refuge in a railroad roundhouse. Strikers set fires that razed 39 buildings and destroyed rolling stock: 104 locomotives and 1,245 freight and passenger cars. On July 22, the National Guard mounted an assault on the strikers, shooting their way out of the roundhouse and killing 20 more people on their way out of the city. After more than a month of rioting and bloodshed in Pittsburgh, President

Digital History, University of Houston (and others), accessed 27 May 2016 Damage estimates ranged from five to 10 million dollars. ''Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate the Railroad Riots in July, 1877''

Harrisburg: L.S. Hart, state printer, 1878, p. 19

online

* DeMichele, Matthew. "Policing protest events: The Great Strike of 1877 and WTO protests of 1999." ''American Journal of Criminal Justice'' 33.1 (2008): 1-18. * Jentz, John B., and Richard Schneirov. “Combat in the Streets: The Railroad Strike of 1877 and Its Consequences.” in ''Chicago in the Age of Capital: Class, Politics, and Democracy during the Civil War and Reconstruction'' (University of Illinois Press, 2012), pp. 194–219

online

* Lesh, Bruce. "Using Primary Sources to Teach the Rail Strike of 1877" ''OAH Magazine of History'' (1999) 13#w pp 38-47. DOI: 10.2307/2516330

online

* Lloyd, John P. "The strike wave of 1877" in ''The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History'' (2009) pp 177-190

online

* Piper, Jessica. "The great railroad strike of 1877: A catalyst for the American labor movement." ''History Teacher'' 47.1 (2013): 93-110

online

* Roediger, David. " '‘Not Only the Ruling Classes to Overcome, but Also the So-Called Mob': Class, Skill and Community in the St. Louis General Strike of 1877." ''Journal of Social History'' 19#2 (1985), pp. 213–39

online

* Rondinole, Troy. "Drifting toward Industrial War: The Great Strike of 1877 and the Coming of a New Era." in ''The Great Industrial War: Framing Class Conflict in the Media, 1865-1950'' (Rutgers University Press, 2010), pp. 38–57

online

* Salvatore, Nick. "Railroad Workers and the Great Strike of 1877," ''Labor History'' (1980) 21#4 pp 522–4

online

* Smith, Shannon M. “‘They Met Force with Force’: African American Protests and Social Status in Louisville’s 1877 Strike.” ''Register of the Kentucky Historical Society'' 115#1 (2017), pp. 1–37

online

* Stowell, David O. ''Streets, Railroads, and the Great Strike of 1877,'' University of Chicago Press, 1999 * Stowell, David O., editor. ''The Great Strikes of 1877,'' University of Illinois Press, 2008 * Stowell, David O. “Albany’s Great Strike of 1877.” ''New York History'' 76#1 , 1995, pp. 31–55

online

* Walker, Samuel C. “Railroad Strike of 1877 in Altoona.” ''Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin'', no. 117, 1967, pp. 18–25. in Altoona, Pennsylvani

online

* White, Richard. ''Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of modern America'' (W.W. Norton, 2011)

online

* Yearley, Clifton K., Jr. "The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Strike of 1877," ''Maryland Historical Magazine'' (1956) 51#3 pp. 118–211.

"The Great Strike"

''

"The B&O Railroad Strike of 1877."

''The Statesman'' (Martinsburg, WV), July 24, 1877. (West Virginia Division of Culture and History) *

online

"Catholics and Labor Unionization"

American Catholic History Classroom, The Catholic University of America; Overview, archives and primary documents

Britannica

Teaching Resources—Maryland State Archives * {{Authority control 1877 in rail transport 1877 in the United States 1877 labor disputes and strikes Riots and civil disorder in Pittsburgh Martinsburg, West Virginia Political repression in the United States Rail transportation labor disputes in the United States 1877 in West Virginia Labor disputes in Illinois Labor disputes in Pennsylvania Labor disputes in West Virginia Labor disputes in Maryland Labor disputes in Missouri Pinkerton (detective agency) July 1877 events August 1877 events September 1877 events

Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

(B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 days later, after it was put down by unofficial militias, the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

, and federal troops. Because of economic problems and pressure on wages by the railroads, workers in numerous other cities, in New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland, into Illinois and Missouri, also went out on strike. An estimated 100 people were killed in the unrest across the country. In Martinsburg, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and other cities, workers burned down and destroyed both physical facilities and the rolling stock

The term rolling stock in the rail transport industry refers to railway vehicles, including both powered and unpowered vehicles: for example, locomotives, freight and passenger cars (or coaches), and non-revenue cars. Passenger vehicles ca ...

of the railroads—engines and railroad cars. Local populations feared that workers were rising in revolution such as the Paris Commune of 1871.

At the time, the workers were not represented by trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

s. The city and state governments were aided by unofficial militias, the National Guard, federal troops and private militias organized by the railroads, who all fought against the workers. Disruption was widespread and at its height, the strikes were supported by about 100,000 workers. With the intervention of federal troops in several locations, most of the strikes were suppressed by early August. Labor continued to work to organize into unions to work for better wages and conditions. Fearing the social disruption, many cities built armories to support the local National Guard units; these defensive buildings still stand as symbols of the effort to suppress the labor unrest of this period.

With public attention on workers' wages and conditions, the B&O in 1880 founded an Employee Relief Association to provide death benefits and some health care. In 1884, it established a worker pension plan. Other improvements were implemented later.

Panic of 1873 and the Long Depression

TheLong Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

, beginning in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

with the financial Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

and lasting 65 months, became the longest economic contraction in American history, including the later more famous, 45-month-long Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s. The failure of the Jay Cooke

Jay Cooke (August 10, 1821 – February 16, 1905) was an American financier who helped finance the Union war effort during the American Civil War and the postwar development of railroads in the northwestern United States. He is generally acknowle ...

bank in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, was followed quickly by that of Henry Clews

Henry Clews (August 14, 1834 – January 31, 1923) was a British-American financier and author.

Early life

Clews was born on August 14, 1834, in Staffordshire, England.Ingham, John N. "Clews, Henry." 'Biographical Dictionary of American Business ...

, and set off a chain reaction of bank failures, temporarily closing the New York stock market.

Unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refe ...

rose dramatically, reaching 14 percent by 1876, many more were severely underemployed, and wages overall dropped to 45% of their previous level. Thousands of American businesses failed, defaulting on more than a billion dollars of debt. One in four laborers in New York were out of work in the winter of 1873-1874. National construction of new rail lines dropped from 7,500 miles of track in 1872 to just 1,600 miles in 1875,Paul Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," in Arthur M. Schlesinger (ed.), ''History of U.S. Political Parties: Volume II, 1860–1910, The Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

of Politics.'' New York: Chelsea House/R.R. Bowker Co., 1973; pg. 1556. and production in iron and steel alone dropped as much as 45%.

Reason for strike

When theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

ended, a boom in railroad construction ensued, with roughly 35,000 miles (55,000 kilometers) of new track being laid from coast to coast between 1866 and 1873. The railroads, then the second-largest employer outside of agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

, required large amounts of capital investment, and thus entailed massive financial risk. Speculators fed large amounts of money into the industry, causing abnormal growth and over-expansion. Jay Cooke's firm, like many other banking firms, invested a disproportionate share of depositors' funds in the railroads, thus laying the track for the ensuing collapse.

In addition to Cooke's direct infusion of capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

in the railroads, the firm had become a federal agent for the government in the government's direct financing of railroad construction. As building new track in areas where land had not yet been cleared or settled required land grants

A land grant is a gift of real estate—land or its use privileges—made by a government or other authority as an incentive, means of enabling works, or as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service. Grants ...

and loans

In finance, a loan is the lending of money by one or more individuals, organizations, or other entities to other individuals, organizations, etc. The recipient (i.e., the borrower) incurs a debt and is usually liable to pay interest on that de ...

that only the government could provide, the use of Jay Cooke's firm as a conduit for federal funding worsened the effects that Cooke's bankruptcy had on the nation's economy.

In the wake of the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, a bitter antagonism between workers and the leaders of industry developed. Immigration from Europe was underway, as was migration of rural workers into the cities, increasing competition for jobs and enabling companies to drive down wages and easily lay off workers. By 1877, 10 percent wage cuts, distrust of capitalists and poor working conditions led to workers conducting numerous railroad strikes that prevented the trains from moving, with spiraling effects in other parts of the economy. Suppressed by violence, workers continued to organize to try to improve their conditions. Management worked to break up such movements, and mainstream society feared labor organizing as signs of revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolut ...

. Tensions lingered well after the depression ended in 1878–79.

Many of the new immigrant workers were Catholics, and their church had forbidden participation in secret societies since 1743, partially as a reaction against the anti-Catholicism of Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

. But by the late 19th century, the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

, a national and predominately European and Catholic organization, had 700,000 members seeking to represent all workers. In 1888 Archbishop James Cardinal Gibbons

James Cardinal Gibbons (July 23, 1834 – March 24, 1921) was a senior-ranking American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Apostolic Vicar of North Carolina from 1868 to 1872, Bishop of Richmond from 1872 to 1877, and as ninth ...

of Baltimore sympathized with the workers and collaborated with other bishops to lift the prohibition against workers joining the KOL. Other workers also took actions, and unrest marked the following decades. In 1886 Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

founded the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

for the skilled craft trades, attracting skilled workers from other groups. Other labor organizing followed. "The Catholic Church and the Knights of Labor"American Catholic History Classroom, The Catholic University of America, accessed 20 May 2016

The strike

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 started on July 14 in

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 started on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

, in response to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

(B&O) cutting wages of workers for the third time in a year. Striking workers would not allow any of the trains, mainly freight trains, to roll until this third wage cut was revoked. West Virginia Governor

The governor of West Virginia is the head of government of West VirginiaWV Constitution article VII, § 5. and the commander-in-chief of the U.S. state, state's West Virginia National Guard, military forces.WV Constitution article VII, § 12. Th ...

Henry M. Mathews

Henry Mason Mathews (March 29, 1834April 28, 1884) was an American military officer, lawyer, and politician in the U.S. State of West Virginia. Mathews served as 7th Attorney General of West Virginia (1873–1877) and 5th Governor of West Virgi ...

sent in National Guard units to restore train service but the soldiers refused to fire on the strikers. The governor then appealed for federal troops.

Maryland

Meanwhile, the Strike also spread intowestern Maryland

upright=1.2, An enlargeable map of Maryland's 23 counties and one independent city

Western Maryland, also known as the Maryland Panhandle, is the portion of the U.S. state of Maryland that typically consists of Washington, Allegany, and Garre ...

to the major railroad hub of Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

, county seat of Allegany County where railway workers stopped freight and passenger traffic.

In Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, the famous Fifth ("Dandy Fifth") and Sixth Regiments of the former state militia, reorganized since the Civil War as the Maryland National Guard

The Maryland Military Department (MMD) is a department of the State of Maryland directed by the adjutant general of Maryland.

The Maryland Military Department consists of the:

*State Operations section, which manages fiscal and administrative du ...

, were called up by Maryland Governor

The Governor of the State of Maryland is the head of government of Maryland, and is the commander-in-chief of the state's National Guard units. The Governor is the highest-ranking official in the state and has a broad range of appointive powers ...

John Lee Carroll

John Lee Carroll (September 30, 1830 – February 27, 1911), a member of the United States Democratic Party, was the 37th Governor of Maryland from 1876 to 1880.

Early life

Carroll was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of Col. Charles Carr ...

, at the request of powerful B. & O. President John Work Garrett

John Work Garrett (July 31, 1820 – September 26, 1884), was an American merchant turned banker who became president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) in 1858 and led the railroad for nearly three decades. The B&O became one of the most ...

. The Fifth marched down North Howard Street from its armory above the old Richmond Market (at present North Howard and West Read Streets) in the Mount Vernon-Belvedere neighborhood and were generally unopposed heading south for the B. & O.'s general headquarters and main depot at the Camden Street Station to board waiting westward trains to Hagerstown and Cumberland.

The Sixth assembled at its armory at East Fayette and North Front Streets (by the old Phoenix Shot Tower) in the Old Town /Jonestown area and headed to Camden. It had to fight its way west through sympathetic Baltimore citizens, rioters and striking workers. The march erupted into bloodshed along Baltimore Street, the main downtown commercial thoroughfare, the way to get to Camden. It was a horrible scene reminiscent of the worst of the bloody "Pratt Street Riots" of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

era in April 1861, over 15 years earlier. When the outnumbered troops of the 6th Regiment finally fired volleys on an attacking crowd, they killed 10 civilians and wounded 25. The rioters injured several members of the National Guard, damaged B. & O. engines and train cars, and burned portions of the train station at South Howard and West Camden Streets. The National Guard was trapped in the Camden Yards

The Oriole Park at Camden Yards is a baseball stadium located in Baltimore, Maryland. It is the home field of Major League Baseball's Baltimore Orioles, and the first of the "retro" major league ballparks constructed during the 1990s and early ...

, besieged by armed rioters until July 21–22, when President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

sent federal troops and the U.S. Marines to Baltimore to restore order.

New York

There were strike actions also further north in Albany,Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

and Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

on other railroad lines. On July 25, 1877, workers gathered on Van Woert Street Rail Crossing in Albany, New York. The workers waited for a train arrival then proceeded to barrage the train with projectiles. The arrival of militiamen caused the crowd to rouse and throw their projectiles at the militia. A second night proceeded of attacks on the rail line. After the second night the mayor rescinded the militia and ordered local police to protect the rail. Workers in the cities in industries other than railroads still attacked them because of how they cut through the cities and dominated city life. Their resentment of the railroads' economic power was expressed in physical attacks against them at a time when many workers' wages were lowered. Protestors "included cross-class elements from other work sites, small businesses, and commercial establishments. Some protestors acted out of solidarity with the strikers, but many more vented militant displeasure against dangerous railroad traffic that crisscrossed urban centers in that area."Scott Molloy, "Book Review: ''Streets, Railroads, and the Great Strike of 1877'' By David O. Stowell"''Technology and Culture'' 41.3 (2000) 636-638, via Project MUSE, accessed 20 May 2016

Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

became the site of the worst violence of related strikes. Thomas Alexander Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

, described as one of the first robber barons, suggested that the strikers should be given "a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread." As in some other cities and towns, local law enforcement officers such as sheriffs, deputies and police refused to fire on the strikers. Several Pennsylvania National Guard

The Pennsylvania National Guard is one of the oldest and largest National Guards in the United States Department of Defense. It traces its roots to 1747 when Benjamin Franklin established the Associators in Philadelphia.

With more than 18,000 pe ...

units were ordered into service by Governor John Hartranft

John Frederick Hartranft (December 16, 1830 – October 17, 1889) was the United States military officer who read the death warrant to the individuals who were executed on July 7, 1865 for conspiring to assassinate American President Abraham Lin ...

, including the 3rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment under the command of Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

George R. Snowden.

On July 21, National Guard members bayoneted and fired on rock-throwing strikers, killing 20 people and wounding 29. Rather than quell the uprising, these actions infuriated the strikers, who retaliated and forced the National Guard to take refuge in a railroad roundhouse. Strikers set fires that razed 39 buildings and destroyed rolling stock: 104 locomotives and 1,245 freight and passenger cars. On July 22, the National Guard mounted an assault on the strikers, shooting their way out of the roundhouse and killing 20 more people on their way out of the city. After more than a month of rioting and bloodshed in Pittsburgh, President

On July 21, National Guard members bayoneted and fired on rock-throwing strikers, killing 20 people and wounding 29. Rather than quell the uprising, these actions infuriated the strikers, who retaliated and forced the National Guard to take refuge in a railroad roundhouse. Strikers set fires that razed 39 buildings and destroyed rolling stock: 104 locomotives and 1,245 freight and passenger cars. On July 22, the National Guard mounted an assault on the strikers, shooting their way out of the roundhouse and killing 20 more people on their way out of the city. After more than a month of rioting and bloodshed in Pittsburgh, President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

sent in federal troops as in West Virginia and Maryland to end the strikes.

Philadelphia

Three hundred miles to the east,Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

strikers battled local National Guard units and set fire to much of Center City before Pennsylvania Governor John Hartranft

John Frederick Hartranft (December 16, 1830 – October 17, 1889) was the United States military officer who read the death warrant to the individuals who were executed on July 7, 1865 for conspiring to assassinate American President Abraham Lin ...

gained assistance and federal troops from President Hayes to put down the uprising.

Reading

Workers inReading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spell ...

, Pennsylvania's third-largest industrial city at the time, also broke out into a strike. This city was home of the engine works and shops of the Philadelphia and Reading Railway

The Reading Company ( ) was a Philadelphia-headquartered railroad that provided passenger and commercial rail transport in eastern Pennsylvania and neighboring states that operated from 1924 until its 1976 acquisition by Conrail.

Commonly called ...

, against which engineers had struck since April 1877. The National Guard shot 16 citizens. Preludes to the massacre included: fresh work stoppage by all classes of the railroad's local workforce; mass marches; blocking of rail traffic; and trainyard arson. Workers burned down the only railroad bridge offering connections to the west, in order to prevent local National Guard companies from being mustered to actions in the state capital of Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in ...

or Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

. Authorities used the National Guard, local police and Pinkerton detectives in an attempt to break the strike.

Philadelphia and Reading Railway management mobilized a private militia, the members of which committed the shootings in the city.

Shamokin

On July 25, 1,000 men and boys, many of them coal miners, marched to the Reading Railroad Depot in Shamokin, east of Sunbury along theSusquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

valley. They looted the depot when the town announced it would pay them only $1/day for emergency public employment. The mayor, who owned coal mines, organized an unofficial militia. It committed 14 civilian shooting casualties, resulting in the deaths of two persons.

Scranton

On August 1, 1877, inScranton

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 U.S. census, Scranton is the largest city in Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Wyoming V ...

in northeast Pennsylvania, one day after railroad workers commenced a strike, a city posse of 51 men armed with new rifles and under the command of William Walker Scranton

William Walker Scranton (April 4, 1844 – December 3, 1916) was an American businessman based in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He became president and manager of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company after his father's death in 1872. The company ...

, general manager of the Lackawanna Iron & Coal Company, returned fire on a group of rioters, strikers, and, most likely, bystanders. The posse immediately killed or fatally wounded four and wounded an undetermined number of others, estimated at 20 to 50, according to different sources.

Pennsylvania Governor Hartranft declared Scranton to be under martial law; it was occupied by state and federal troops armed with Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

The Gatling gun's operation centered on a c ...

s. Later the posse leader and about 20 of his men were charged with assault and murder. They were all acquitted. Under military occupation, and suffering the effects of protracted violence against them, the miners ended their strike without achieving any of their demands.

Illinois

On July 24, rail traffic inChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

was paralyzed when angry mobs of unemployed citizens wreaked havoc in the rail yards, shutting down both the Baltimore and Ohio

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

and the Illinois Central

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also c ...

railroads. Soon, other railroads throughout the state were brought to a standstill, with demonstrators shutting down railroad traffic in Bloomington, Aurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

, Peoria, Decatur, Urbana __NOTOC__

Urbana can refer to:

Places Italy

*Urbana, Italy

United States

*Urbana, Illinois

**Urbana (conference), a Christian conference formerly held in Urbana, Illinois

*Urbana, Indiana

* Urbana, Iowa

*Urbana, Kansas

* Urbana, Maryland

*Urbana, ...

and other rail centers throughout Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

. In sympathy, coal miners in the pits at Braidwood, LaSalle, Springfield, and Carbondale went on strike as well. In Chicago, the Workingmen's Party

The Workingmen's Party of the United States (WPUS), established in 1876, was one of the first Marxist-influenced political parties in the United States. It is remembered as the forerunner of the Socialist Labor Party of America.

Organizational ...

organized demonstrations that drew crowds of 20,000 people.

Judge Thomas Drummond

Captain Thomas Drummond (10 October 1797 – 15 April 1840), from Edinburgh was a Scottish army officer, civil engineer and senior public official. He used the Drummond light which was employed in the trigonometrical survey of Great Britain an ...

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (in case citations, 7th Cir.) is the U.S. federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the courts in the following districts:

* Central District of Illinois

* Northern District of ...

, who was overseeing numerous railroads that had declared bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debto ...

in the wake of the earlier financial Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, ruled that "A strike or other unlawful interference with the trains will be a violation of the United States law, and the court will be bound to take notice of it and enforce the penalty." Drummond told the U.S. Marshals to protect the railroads, and asked for federal troops to enforce his decision: he subsequently had strikers arrested and tried them for contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

.

The Mayor of Chicago

The mayor of Chicago is the chief executive of city government in Chicago, Illinois, the third-largest city in the United States. The mayor is responsible for the administration and management of various city departments, submits proposals and ...

, Monroe Heath, recruited 5,000 men as an unofficial militia, asking for help in restoring order. They were partially successful, and shortly thereafter were reinforced by the arrival of the Illinois National Guard

The Illinois National Guard comprises both Army National Guard and Air National Guard components of Illinois. As of 2013, the Illinois National Guard has approximately 13,200 members. The National Guard is the only United States military force em ...

and U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

troops, mobilized by the governor. On July 25, violence between police and the mob erupted, with events reaching a peak the following day. These blood-soaked confrontations between police and enraged mobs are known as the Battle of the Viaduct as they took place near the Halsted Street viaduct, although confrontations also took place at nearby 16th Street, on 12th, and on Canal Street. The headline of the ''Chicago Times

The ''Chicago Times'' was a newspaper in Chicago from 1854 to 1895, when it merged with the ''Chicago Herald'', to become the ''Chicago Times-Herald''. The ''Times-Herald'' effectively disappeared in 1901 when it merged with the ''Chicago Record' ...

'' screamed, "Terrors Reign, The Streets of Chicago Given Over to Howling Mobs of Thieves and Cutthroats." Order was finally restored. An estimated 20 men and boys died, none of whom were law enforcement or troops; scores more were wounded, and the loss of property was valued in the millions of dollars.

Missouri

On July 21, workers in the industrial rail hub ofEast St. Louis

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

, Illinois, halted all freight traffic, with the city remaining in the control of the strikers for almost a week. The St. Louis Workingman's Party led a group of approximately 500 men across the Missouri River in an act of solidarity with the nearly 1,000 workers on strike. It was a catalyst for labor unrest spreading, with thousands of workers in several industries striking for the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

and a ban on child labor

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

. This was the first such general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coa ...

in the United States.

The strike on both sides of the river was ended after the governor appealed for help and gained the intervention of some 3,000 federal troops and 5,000 deputized special police. These armed forces killed at least eighteen people in skirmishes around the city. On July 28, 1877, they took control of the Relay Depot, the command center for the uprising, and arrested some seventy strikers.

Strike ends

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 began to lose momentum when President Hayes sent federal troops from city to city. These troops suppressed strike after strike, until approximately 45 days after it had started, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was over.Aftermath and legacy

San Francisco riot of 1877

Momentum from the East Coast strikes and the long-brewing anti-Chinese sentiment led to three days of deadly violence. A rally in support of workers' rights quickly turned into violence directed at the city's Chinese residents.Economic effects

Strikers in Pittsburgh burned in total 39 buildings, 104 engines, 46–66 passenger cars, and 1,200–1,383 freight cars."The Great Railroad Strike of 1877"- Digital History ID 1097Digital History, University of Houston (and others), accessed 27 May 2016 Damage estimates ranged from five to 10 million dollars. ''Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate the Railroad Riots in July, 1877''

Harrisburg: L.S. Hart, state printer, 1878, p. 19

Labor relations

After the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, union organizers planned for their next battles while politicians and business leaders took steps to prevent a repetition of this chaos. Many states enacted conspiracy statutes. States formed new National Guard units and constructed armories in numerous industrial cities. For workers and employers alike, the strikes had shown the power of workers in combination to challenge the status quo. A National Guard member in Pittsburgh, ordered to break the 1877 strike, pointed out that the workers were driven by "one spirit and one purpose among them – that they were justified in resorting to any means to break down the power of the corporations." Unions became better organized as well as more competent, and the number of strikes increased. The tumultuous Knights of Labor grew to be a national organization of predominately white Catholic workers, numbering 700,000 by the early 1880s. In the 1880s nearly 10,000 strike actions and lockouts took place. In 1886 nearly 700,000 workers went on strike. Business leaders strengthened their opposition to the unions, often firing men who tried to organize or join them. Nonetheless, the labor movement continued to grow. One result of the strike was increased public awareness of the grievances of railroad workers. On May 1, 1880, the B&O Railroad, which had the lowest wage rate of any major railroad, established the Baltimore and Ohio Employees' Relief Association, which provided coverage for sickness, injury from accidents, and a death benefit. In 1884, the B&O became the first major employer to offer apension plan

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payment ...

.

National Guard

Militias had almost completely disappeared in the Midwest after the Civil War, leaving many cities defenseless to civil unrest. In response to the Great Strike, West Virginia GovernorHenry M. Mathews

Henry Mason Mathews (March 29, 1834April 28, 1884) was an American military officer, lawyer, and politician in the U.S. State of West Virginia. Mathews served as 7th Attorney General of West Virginia (1873–1877) and 5th Governor of West Virgi ...

was the first state commander-in-chief to call-up militia units to restore peace. This action has been viewed in retrospect as a catalyst that would transform the National Guard. In the years to come the Guard would quell strikers and double their forces; in the years 1886-1895, the Guard put down 328 civil disorders, mostly in the industrial states of Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio and New York; workers came to see the guardsmen as tools of their employers. Attempts to utilize the National Guard to quell violent outbreaks in 1877 highlighted its ineffectiveness, and in some cases its propensity to side with strikers and rioters. In response, as earlier riots in the mid-1800s had prompted the modernization of police forces, the violence of 1877 provided the impetus for modernizing the National Guard, "to aid the civil officers, to suppress or prevent riot or insurrections."

Commemoration

In 2003 the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Martinsburg Shops, where the strike began, were declared aNational Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places liste ...

.Michael Caplinger and John Bond (October, 2003) , National Park Service and

In 2013 a historical marker commemorating the event was placed in Baltimore, MD, by the Maryland Historical Trust

The Maryland Historical Trust is an agency of Maryland Department of Planning and serves as the Maryland State Historic Preservation Office. The agency serves to assist in research, conservation, and education, of Maryland's historical and cultural ...

and Maryland State Highway Administration

The Maryland State Highway Administration (abbreviated MDOT SHA or simply SHA) is the state transportation business unit responsible for maintaining Maryland's numbered highways outside Baltimore City. Formed originally under authority of the ...

. Its inscription reads:

The first national strike began July 16, 1877, with Baltimore and Ohio Railroad workers in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland. It spread across the nation halting rail traffic and closing factories in reaction to widespread worker discontent over wage cuts and conditions during a national depression. Broken by Federal troops in early August, the strike energized the labor movement and was precursor to labor unrest in the 1880s and 1890s.Another was placed in 1978 in Martinsburg, WV by the West Virginia Department of Culture and History.

Posse Comitatus Act

The use of federal troops prompted bipartisan support for the 1878Posse Comitatus Act

The Posse Comitatus Act is a United States federal law (, original at ) signed on June 18, 1878, by President Rutherford B. Hayes which limits the powers of the federal government in the use of federal military personnel to enforce domestic p ...

, limiting the power of the president to use federal troops for domestic law enforcement.

See also

*Baltimore railroad strike of 1877

The Baltimore railroad strike of 1877 involved several days of work stoppage and violence in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1877. It formed a part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, during which widespread civil unrest spread nationwide following ...

* Chicago railroad strike of 1877

The Chicago railroad strike of 1877 was a series of work stoppages and civil unrest in Chicago, Illinois, which occurred as part of the larger national strikes and rioting of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Meetings of working men in Chicago ...

* Pittsburgh railroad strike of 1877

The Pittsburgh railway strike occurred in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania as part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. It was one of many incidents of strikes, labor unrest and violence in cities across the United States, including several in Pennsy ...

* 1877 St. Louis general strike

The 1877 St. Louis general strike was one of the first general strikes in the United States. It grew out of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The strike was largely organized by the Knights of Labor and the Marxist-leaning Workingmen's Party, ...

* Scranton general strike

* 1877 Shamokin uprising

The 1877 Shamokin uprising occurred in Shamokin, Pennsylvania, in July 1877, as one of the several cities in the state where strikes occurred as part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The Great Strike was the first in the United States in w ...

* Great Railroad Strike of 1922

The Great Railroad Strike of 1922, commonly known as the railroad shopmen, Railway Shopmen's Strike, was a nationwide Strike action, strike of railroad workers in the United States. Launched on July 1, 1922, by seven of the sixteen List of Amer ...

* History of rail transport in the United States

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

* List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

Listed are major episodes of civil unrest in the United States. This list does not include the numerous incidents of destruction and violence associated with various sporting events.

18th century

*1783 – Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, June 20. ...

References

Further reading

* *online

* DeMichele, Matthew. "Policing protest events: The Great Strike of 1877 and WTO protests of 1999." ''American Journal of Criminal Justice'' 33.1 (2008): 1-18. * Jentz, John B., and Richard Schneirov. “Combat in the Streets: The Railroad Strike of 1877 and Its Consequences.” in ''Chicago in the Age of Capital: Class, Politics, and Democracy during the Civil War and Reconstruction'' (University of Illinois Press, 2012), pp. 194–219

online

* Lesh, Bruce. "Using Primary Sources to Teach the Rail Strike of 1877" ''OAH Magazine of History'' (1999) 13#w pp 38-47. DOI: 10.2307/2516330

online

* Lloyd, John P. "The strike wave of 1877" in ''The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History'' (2009) pp 177-190

online

* Piper, Jessica. "The great railroad strike of 1877: A catalyst for the American labor movement." ''History Teacher'' 47.1 (2013): 93-110

online

* Roediger, David. " '‘Not Only the Ruling Classes to Overcome, but Also the So-Called Mob': Class, Skill and Community in the St. Louis General Strike of 1877." ''Journal of Social History'' 19#2 (1985), pp. 213–39

online

* Rondinole, Troy. "Drifting toward Industrial War: The Great Strike of 1877 and the Coming of a New Era." in ''The Great Industrial War: Framing Class Conflict in the Media, 1865-1950'' (Rutgers University Press, 2010), pp. 38–57

online

* Salvatore, Nick. "Railroad Workers and the Great Strike of 1877," ''Labor History'' (1980) 21#4 pp 522–4

online

* Smith, Shannon M. “‘They Met Force with Force’: African American Protests and Social Status in Louisville’s 1877 Strike.” ''Register of the Kentucky Historical Society'' 115#1 (2017), pp. 1–37

online

* Stowell, David O. ''Streets, Railroads, and the Great Strike of 1877,'' University of Chicago Press, 1999 * Stowell, David O., editor. ''The Great Strikes of 1877,'' University of Illinois Press, 2008 * Stowell, David O. “Albany’s Great Strike of 1877.” ''New York History'' 76#1 , 1995, pp. 31–55

online

* Walker, Samuel C. “Railroad Strike of 1877 in Altoona.” ''Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin'', no. 117, 1967, pp. 18–25. in Altoona, Pennsylvani

online

* White, Richard. ''Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of modern America'' (W.W. Norton, 2011)

online

* Yearley, Clifton K., Jr. "The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Strike of 1877," ''Maryland Historical Magazine'' (1956) 51#3 pp. 118–211.

Primary sources

"The Great Strike"

''

Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

,'' August 11, 1877. (Catskill Archive)

"The B&O Railroad Strike of 1877."

''The Statesman'' (Martinsburg, WV), July 24, 1877. (West Virginia Division of Culture and History) *

online

Popular history

"Catholics and Labor Unionization"

American Catholic History Classroom, The Catholic University of America; Overview, archives and primary documents

Britannica

External links

Teaching Resources—Maryland State Archives * {{Authority control 1877 in rail transport 1877 in the United States 1877 labor disputes and strikes Riots and civil disorder in Pittsburgh Martinsburg, West Virginia Political repression in the United States Rail transportation labor disputes in the United States 1877 in West Virginia Labor disputes in Illinois Labor disputes in Pennsylvania Labor disputes in West Virginia Labor disputes in Maryland Labor disputes in Missouri Pinkerton (detective agency) July 1877 events August 1877 events September 1877 events