Gouverneur K. Warren on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

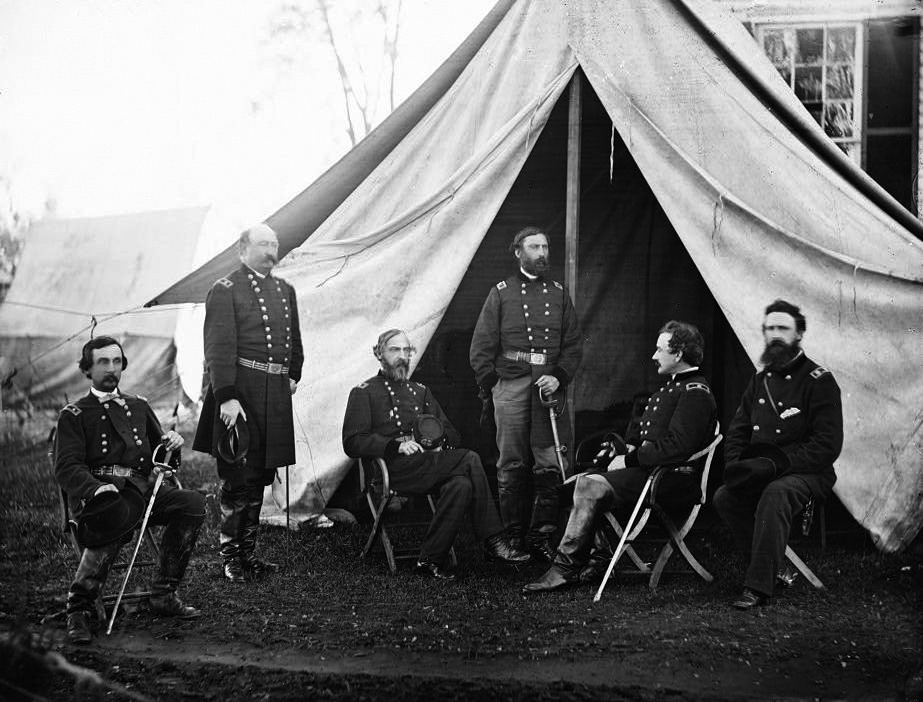

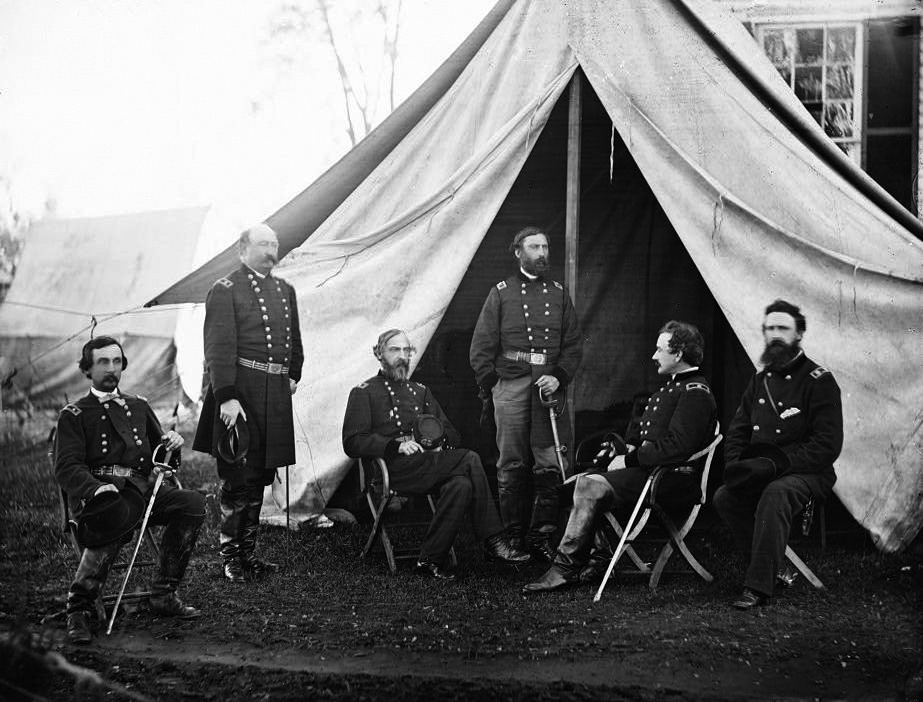

Gouverneur Kemble Warren (January 8, 1830 – August 8, 1882) was an American

Warren was promoted to

Warren was promoted to  At the

At the

2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. . * Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler. "Gouverneur Kemble Warren." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Wittenberg, Eric J. ''Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan''. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2002. .

civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

and Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. He is best remembered for arranging the last-minute defense of Little Round Top

Little Round Top is the smaller of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the companion to the adjacent, taller hill named Big Round Top. It was the site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederate troops against the Union left f ...

during the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

and is often referred to as the "Hero of Little Round Top". His subsequent service as a corps commander and his remaining military career were ruined during the Battle of Five Forks

The Battle of Five Forks was fought on April 1, 1865, southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, around the road junction of Five Forks, Dinwiddie County, at the end of the Siege of Petersburg, near the conclusion of the American Civil War.

The Union ...

, when he was relieved of command of the V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army ...

by Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close a ...

, who claimed that Warren had moved too slowly.

Early life

Warren was born in Cold Spring, Putnam County,New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, and named for Gouverneur Kemble

Gouverneur Kemble (January 25, 1786 – September 18, 1875) was a two-term United States Congressman, diplomat and industrialist. He helped found the West Point Foundry, a major producer of artillery during the American Civil War.

Early life and ...

, a prominent local Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

, diplomat, industrialist, and owner of the West Point Foundry. His sister, Emily Warren Roebling

Emily Warren Roebling (September 23, 1843 – February 28, 1903) was an engineer known for her contributions over a period of more than 10 years to the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge after her husband Washington Roebling developed caiss ...

, would later play a significant role in the building of the Brooklyn Bridge. He entered the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

across the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

from his hometown at age 16 and graduated second in his class of 44 cadets in 1850.Eicher, pp. 554–55. He was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

in the Corps of Topographical Engineers

The U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers was a branch of the United States Army authorized on 4 July 1838. It consisted only of officers who were handpicked from West Point and was used for mapping and the design and construction of federal ...

. In the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

years he worked on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

, on transcontinental railroad surveys, and mapped the trans-Mississippi West. He served as the engineer on William S. Harney's Battle of Ash Hollow in the Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

in 1855, where he saw his first combat.Heidler, pp. 2062–63.

He took part in studies of possible transcontinental railroad routes, creating the first comprehensive map of the United States west of the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

in 1857. This required extensive explorations of the vast Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

, including Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

, North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

, part of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, and part of Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

.

One region he surveyed was the Minnesota River Valley, a valley much larger than what would be expected from the low-flow Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

. In some places the valley is 5 miles (8 km) wide and 250 feet (80 m) deep. Warren first explained the hydrology of the region in 1868, attributing the gorge to a massive river, which drained Lake Agassiz

Lake Agassiz was a large glacial lake in central North America. Fed by glacial meltwater at the end of the last glacial period, its area was larger than all of the modern Great Lakes combined.

First postulated in 1823 by William H. Keating, i ...

between 11,700 and 9,400 years ago. The great river was named Glacial River Warren in his honor after his death.

Civil War

At the start of the war, Warren was afirst lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

and mathematics instructor at the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

. He helped raise a local regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

for service in the Union Army and was appointed lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

of the 5th New York Infantry on May 14, 1861. Warren and his regiment saw their first combat at the Battle of Big Bethel

The Battle of Big Bethel was one of the earliest land battles of the American Civil War. It took place on the Virginia Peninsula, near Newport News, on June 10, 1861.

Virginia's decision to secede from the Union had been ratified by popular ...

in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

on June 10, arguably the first major land engagement of the war. He was promoted to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

and regimental commander on September 10.

In the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, Warren commanded his regiment at the Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virg ...

and also assisted the chief topographical engineer of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys (November 2, 1810December 27, 1883), was a career United States Army officer, civil engineer, and a Union General in the American Civil War. He served in senior positions in the Army of the Potomac, including division ...

, by leading reconnaissance missions and drawing detailed maps of appropriate routes for the army in its advance up the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the n ...

. He commanded a small brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

...

(3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army ...

) during the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

consisting of his own 5th New York along with the 10th New York. At Gaines Mill, he was bruised in the knee by a shell fragment, but remained on the field. He continued to lead the brigade at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

, suffering heavy casualties in a heroic stand against an overwhelming enemy assault,Wittenberg, p. 117. and at Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, where the V Corps was in reserve and saw no combat.

Warren was promoted to

Warren was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

on September 26, 1862, and he and his brigade went to the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Bur ...

in December, but again were held in reserve and saw no action. When Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

reorganized the Army of the Potomac in February 1863, he named Warren his chief topographical engineer and then chief engineer. As chief engineer, Warren was commended for his service in the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

.

At the start of the Gettysburg Campaign, as Confederate General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

began his invasion of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, Warren advised Hooker on the routes the Army should take in pursuit. On the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

, July 2, 1863, Warren initiated the defense of Little Round Top

Little Round Top is the smaller of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the companion to the adjacent, taller hill named Big Round Top. It was the site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederate troops against the Union left f ...

, recognizing the importance of the undefended position on the left flank of the Union Army, and directing, on his own initiative, the brigade of Col. Strong Vincent to occupy it just minutes before it was attacked. Warren suffered a minor neck wound during the Confederate assault.

Promoted to major general after Gettysburg (August 8, 1863), Warren commanded the II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

from August 1863 until March 1864, replacing the wounded Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, and distinguishing himself at the Battle of Bristoe Station

The Battle of Bristoe Station was fought on October 14, 1863, at Bristoe Station, Virginia, between Union forces under Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren and Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill during the Bristoe Campaign of the Ameri ...

. On March 13, 1865, he was brevetted to major general in the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

for his actions at Bristoe Station. During the Mine Run Campaign

The Battle of Mine Run, also known as Payne's Farm, or New Hope Church, or the Mine Run campaign (November 27 – December 2, 1863), was conducted in Orange County, Virginia, in the American Civil War.

An unsuccessful attempt of the Union ...

, Warren's corps was ordered to attack Lee's army, but he perceived that a trap had been laid and refused the order from army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

. Although initially angry at Warren, Meade acknowledged that he had been right. Upon Hancock's return from medical leave, and the spring 1864 reorganization of the Army of the Potomac, Warren assumed command of the V Corps and led it through the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

, the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

, and the Appomattox Campaign.

During these Virginia campaigns, Warren established a reputation of bringing his engineering traits of deliberation and caution to the role of infantry corps commander. He won the Battle of Globe Tavern

The Battle of Globe Tavern, also known as the Second Battle of the Weldon Railroad, fought August 18–21, 1864, south of Petersburg, Virginia, was the second attempt of the Union Army to sever the Weldon Railroad during the siege of Petersburg ...

, August 18 to August 20, 1864, cutting the Weldon Railroad, a vital supply route north to Petersburg. He also won a limited success in the Battle of Peebles' Farm in September 1864, carrying a part of the Confederate lines protecting supplies moving to Petersburg on the Boydton Plank Road.

The aggressive Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close a ...

, a key subordinate of Lt. Gen.

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, was dissatisfied with Warren's performance. He was angry at Warren's corps for supposedly obstructing roads after the Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Ar ...

and its cautious actions during the Siege of Petersburg. At the beginning of the Appomattox Campaign, Sheridan requested that the VI Corps 6 Corps, 6th Corps, Sixth Corps, or VI Corps may refer to:

France

* VI Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry formation of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VI Corps (Grande Armée), a formation of the Imperial French army du ...

be assigned to his pursuit of Lee's army, but Grant insisted that the V Corps was better positioned. He gave Sheridan written permission to relieve Warren if he felt it was justified "for the good of the service".Wittenberg, p. 119. Grant later wrote in his ''Personal Memoirs'',

At the

At the Battle of Five Forks

The Battle of Five Forks was fought on April 1, 1865, southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, around the road junction of Five Forks, Dinwiddie County, at the end of the Siege of Petersburg, near the conclusion of the American Civil War.

The Union ...

on April 1, 1865, Sheridan judged that the V Corps had moved too slowly into the attack, and criticised Warren fiercely for not being at the front of his columns. Warren had been held up, searching for Samuel W. Crawford

Samuel Wylie Crawford (November 8, 1829 – November 3, 1892) was a United States Army surgeon and a Union general in the American Civil War.

He served as a surgeon at Fort Sumter, South Carolina during the confederate bombardment in 1861. ...

’s division, which had gone astray in the woods. But overall, he had handled his corps efficiently, and their attack had carried the day at Five Forks, arguably the pivotal battle of the final days. Nevertheless, Sheridan relieved Warren of command on the spot. He was assigned to the defenses of Petersburg and then briefly to command of the Department of Mississippi.

Post-war

Humiliated by Sheridan, Warren resigned his commission as major general of volunteers in protest on May 27, 1865, reverting to his permanent rank asmajor

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

in the Corps of Engineers. He served as an engineer for 17 years, building railroads, with assignments along the Mississippi River, achieving the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1879. But the career that had shown so much promise at Gettysburg was ruined. He urgently requested a court of inquiry to exonerate him from the stigma of Sheridan's action. Numerous requests were ignored or refused until Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

retired from the presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified by ...

. President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

ordered a court of inquiry that convened in 1879 and, after hearing testimony from dozens of witnesses over 100 days, found that Sheridan's relief of Warren had been unjustified. On November 21, 1881 President Chester Alan Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A ...

directed that the findings be published; no other action was taken. Unfortunately for Warren, these results were not published until after his death.

In 1867, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

Warren's last assignment in the Army was as district engineer for Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, where he died of complications from diabetes on August 8, 1882. He was buried in the Island Cemetery

The Common Burying Ground and Island Cemetery are a pair of separate cemeteries on Farewell and Warner Street in Newport, Rhode Island. Together they contain over 5,000 graves, including a colonial-era slave cemetery and Jewish graves. The pair ...

in Newport in civilian clothes and without military honors at his own request. His last words were, "The flag! The flag!"

Legacy

A bronze statue of Warren stands on Little Round Top in Gettysburg National Military Park. It was created byKarl Gerhardt

Karl Gerhardt was a United States sculptor, best known for his death mask of President Ulysses S. Grant and a portrait bust of Mark Twain.

Biography

Karl Gerhardt was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 7, 1853.

He attended Phillip ...

(1853–1940) and dedicated in 1888. Another bronze statue, by Henry Baerer

Henry Baerer (1837-1908) was an American sculptor born in Munich, Germany.

Works include:

* two versions of the Puck magazine mascot on the Puck Building, New York (1886)

* Bronze bust of Beethoven for a monument in Central Park (1894)

** N ...

(1837–1908), was erected in the Grand Army Plaza

Grand Army Plaza, originally known as Prospect Park Plaza, is a public plaza that comprises the northern corner and the main entrance of Prospect Park in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. It consists of concentric oval rings arranged as s ...

, Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

. It depicts Warren standing in uniform, with field binoculars on a granite pedestal, made of stone quarried at Little Round Top.

Reflecting a pattern of naming many Washington, DC streets in newly developed areas in the Capital after Civil War generals, an east–west street in the Northwest quadrant is named Warren Street, NW.

The United States Army Transport was named for the general.

The G. K. Warren Prize The G. K. Warren Prize is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "for noteworthy and distinguished accomplishment in fluviatile geology and closely related aspects of the geological sciences." Named in honor of Gouverneur Kemble Warren, ...

is awarded approximately every four years by the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

. It is funded by a gift from his daughter, Miss Emily B. Warren, in memory of her father.

Mount Warren in California is named in his honor.Francis Peloubet Farquhar (1926), ''Place Names of the High Sierra'', Publisher: Sierra Club, p. 101

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-rank ...

Notes

References

* Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Grant, Ulysses S.br>''Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant''2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. . * Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler. "Gouverneur Kemble Warren." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Wittenberg, Eric J. ''Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan''. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2002. .

Further reading

* Jordan, David M. ''"Happiness Is Not My Companion": The Life of General G. K. Warren''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001. .External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Warren, Gouverneur K. 1830 births 1882 deaths People of New York (state) in the American Civil War United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers United States Military Academy alumni Union Army generals People from Cold Spring, New York American civil engineers Burials in Rhode Island Engineers from New York (state) Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences