Gladiator on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the

Early literary sources seldom agree on the origins of gladiators and the gladiator games. In the late 1st century BC, Nicolaus of Damascus believed they were Etruscan. A generation later,

Early literary sources seldom agree on the origins of gladiators and the gladiator games. In the late 1st century BC, Nicolaus of Damascus believed they were Etruscan. A generation later,

Gladiatorial games offered their sponsors extravagantly expensive but effective opportunities for self-promotion, and gave their clients and potential voters exciting entertainment at little or no cost to themselves. Gladiators became big business for trainers and owners, for politicians on the make and those who had reached the top and wished to stay there. A politically ambitious '' privatus'' (private citizen) might postpone his deceased father's ''munus'' to the election season, when a generous show might drum up votes; those in power and those seeking it needed the support of the plebeians and their tribunes, whose votes might be won with the mere promise of an exceptionally good show. Sulla, during his term as ''

Gladiatorial games offered their sponsors extravagantly expensive but effective opportunities for self-promotion, and gave their clients and potential voters exciting entertainment at little or no cost to themselves. Gladiators became big business for trainers and owners, for politicians on the make and those who had reached the top and wished to stay there. A politically ambitious '' privatus'' (private citizen) might postpone his deceased father's ''munus'' to the election season, when a generous show might drum up votes; those in power and those seeking it needed the support of the plebeians and their tribunes, whose votes might be won with the mere promise of an exceptionally good show. Sulla, during his term as ''

This has been interpreted as a ban on gladiatorial combat. Yet, in the last year of his life, Constantine wrote a letter to the citizens of Hispellum, granting its people the right to celebrate his rule with gladiatorial games.

In 365, Valentinian I (r. 364–375) threatened to fine a judge who sentenced Christians to the arena and in 384 attempted, like most of his predecessors, to limit the expenses of ''gladiatora munera''.

In 393,

This has been interpreted as a ban on gladiatorial combat. Yet, in the last year of his life, Constantine wrote a letter to the citizens of Hispellum, granting its people the right to celebrate his rule with gladiatorial games.

In 365, Valentinian I (r. 364–375) threatened to fine a judge who sentenced Christians to the arena and in 384 attempted, like most of his predecessors, to limit the expenses of ''gladiatora munera''.

In 393,

The earliest types of gladiator were named after Rome's enemies of that time: the Samnite,

The earliest types of gladiator were named after Rome's enemies of that time: the Samnite,  Two other sources of gladiators, found increasingly during the Principate and the relatively low military activity of the

Two other sources of gladiators, found increasingly during the Principate and the relatively low military activity of the

Gladiator games were advertised well beforehand, on billboards that gave the reason for the game, its editor, venue, date and the number of paired gladiators (''ordinarii'') to be used. Other highlighted features could include details of ''venationes'', executions, music and any luxuries to be provided for the spectators, such as an awning against the sun, water sprinklers, food, drink, sweets and occasionally "door prizes". For enthusiasts and gamblers, a more detailed program (''libellus'') was distributed on the day of the ''munus'', showing the names, types and match records of gladiator pairs, and their order of appearance. Left-handed gladiators were advertised as a rarity; they were trained to fight right-handers, which gave them an advantage over most opponents and produced an interestingly unorthodox combination.

The night before the ''munus'', the gladiators were given a banquet and opportunity to order their personal and private affairs; Futrell notes its similarity to a ritualistic or sacramental "last meal". These were probably both family and public events which included even the ''noxii'', sentenced to die in the arena the following day; and the ''damnati'', who would have at least a slender chance of survival. The event may also have been used to drum up more publicity for the imminent game..

Gladiator games were advertised well beforehand, on billboards that gave the reason for the game, its editor, venue, date and the number of paired gladiators (''ordinarii'') to be used. Other highlighted features could include details of ''venationes'', executions, music and any luxuries to be provided for the spectators, such as an awning against the sun, water sprinklers, food, drink, sweets and occasionally "door prizes". For enthusiasts and gamblers, a more detailed program (''libellus'') was distributed on the day of the ''munus'', showing the names, types and match records of gladiator pairs, and their order of appearance. Left-handed gladiators were advertised as a rarity; they were trained to fight right-handers, which gave them an advantage over most opponents and produced an interestingly unorthodox combination.

The night before the ''munus'', the gladiators were given a banquet and opportunity to order their personal and private affairs; Futrell notes its similarity to a ritualistic or sacramental "last meal". These were probably both family and public events which included even the ''noxii'', sentenced to die in the arena the following day; and the ''damnati'', who would have at least a slender chance of survival. The event may also have been used to drum up more publicity for the imminent game..

The entertainments often began with ''venationes'' (beast hunts) and ''bestiarii'' (beast fighters). Next came the ''ludi meridiani'', which were of variable content but usually involved executions of ''noxii'', some of whom were condemned to be subjects of fatal re-enactments, based on Greek or Roman myths. Gladiators may have been involved in these as executioners, though most of the crowd, and the gladiators themselves, preferred the "dignity" of an even contest. There were also comedy fights; some may have been lethal. A crude Pompeian graffito suggests a burlesque of musicians, dressed as animals named ''Ursus tibicen'' (flute-playing bear) and ''Pullus cornicen'' (horn-blowing chicken), perhaps as accompaniment to clowning by '' paegniarii'' during a "mock" contest of the ''ludi meridiani''.

The entertainments often began with ''venationes'' (beast hunts) and ''bestiarii'' (beast fighters). Next came the ''ludi meridiani'', which were of variable content but usually involved executions of ''noxii'', some of whom were condemned to be subjects of fatal re-enactments, based on Greek or Roman myths. Gladiators may have been involved in these as executioners, though most of the crowd, and the gladiators themselves, preferred the "dignity" of an even contest. There were also comedy fights; some may have been lethal. A crude Pompeian graffito suggests a burlesque of musicians, dressed as animals named ''Ursus tibicen'' (flute-playing bear) and ''Pullus cornicen'' (horn-blowing chicken), perhaps as accompaniment to clowning by '' paegniarii'' during a "mock" contest of the ''ludi meridiani''.

Image:Roman myrmillones gladiator helmet with relief depicting scenes from the Trojan War from Herculaneum 1st century CE Bronze 01.jpg, Murmillo gladiator helmet with relief depicting scenes from the Trojan War; from Herculaneum

Image:Roman gladiator helmet found in the gladiator barracks in Pompeii 1st century CE.jpg, Helmet found in the gladiator barracks in Pompeii

Image:Roman gladiator helmet from Herculaneum Iron 1st century CE.jpg, Iron gladiator helmet from Herculaneum

Image:Gladiator helmet found in Pompeii and richly decorated with scenes of Greek mythology, Gladiators – Death and Triumph at the Colosseum exhibition, Museum und Park Kalkriese (9618142634).jpg, Gladiator helmet found in Pompeii, with scenes from

Combats between experienced, well trained gladiators demonstrated a considerable degree of stagecraft. Among the cognoscenti, bravado and skill in combat were esteemed over mere hacking and bloodshed; some gladiators made their careers and reputation from bloodless victories. Suetonius describes an exceptional ''munus'' by Nero, in which no-one was killed, "not even ''noxii'' (enemies of the state)." Fagan speculates that Nero was perversely defying the crowd's expectations, or perhaps trying to please a different kind of crowd.

Trained gladiators were expected to observe professional rules of combat. Most matches employed a senior referee (''summa rudis'') and an assistant, shown in mosaics with long staffs (''rudes'') to caution or separate opponents at some crucial point in the match. Referees were usually retired gladiators whose decisions, judgement and discretion were, for the most part, respected; they could stop bouts entirely, or pause them to allow the combatants rest, refreshment and a rub-down.

Ludi and ''munera'' were accompanied by music, played as interludes, or building to a "frenzied crescendo" during combats, perhaps to heighten the suspense during a gladiator's appeal; blows may have been accompanied by trumpet-blasts. The Zliten mosaic in Libya (circa 80–100 AD) shows musicians playing an accompaniment to provincial games (with gladiators, ''bestiarii'', or ''venatores'' and prisoners attacked by beasts). Their instruments are a long straight trumpet ('' tubicen''), a large curved horn ('' Cornu'') and a water organ (''hydraulis''). Similar representations (musicians, gladiators and ''bestiari'') are found on a tomb relief in Pompeii.

Combats between experienced, well trained gladiators demonstrated a considerable degree of stagecraft. Among the cognoscenti, bravado and skill in combat were esteemed over mere hacking and bloodshed; some gladiators made their careers and reputation from bloodless victories. Suetonius describes an exceptional ''munus'' by Nero, in which no-one was killed, "not even ''noxii'' (enemies of the state)." Fagan speculates that Nero was perversely defying the crowd's expectations, or perhaps trying to please a different kind of crowd.

Trained gladiators were expected to observe professional rules of combat. Most matches employed a senior referee (''summa rudis'') and an assistant, shown in mosaics with long staffs (''rudes'') to caution or separate opponents at some crucial point in the match. Referees were usually retired gladiators whose decisions, judgement and discretion were, for the most part, respected; they could stop bouts entirely, or pause them to allow the combatants rest, refreshment and a rub-down.

Ludi and ''munera'' were accompanied by music, played as interludes, or building to a "frenzied crescendo" during combats, perhaps to heighten the suspense during a gladiator's appeal; blows may have been accompanied by trumpet-blasts. The Zliten mosaic in Libya (circa 80–100 AD) shows musicians playing an accompaniment to provincial games (with gladiators, ''bestiarii'', or ''venatores'' and prisoners attacked by beasts). Their instruments are a long straight trumpet ('' tubicen''), a large curved horn ('' Cornu'') and a water organ (''hydraulis''). Similar representations (musicians, gladiators and ''bestiari'') are found on a tomb relief in Pompeii.

The body of a gladiator who had died well was placed on a couch of Libitina and removed with dignity to the arena morgue, where the corpse was stripped of armour, and probably had its throat cut as confirmation of death. The Christian author

The body of a gladiator who had died well was placed on a couch of Libitina and removed with dignity to the arena morgue, where the corpse was stripped of armour, and probably had its throat cut as confirmation of death. The Christian author

Among the most admired and skilled ''auctorati'' were those who, having been granted manumission, volunteered to fight in the arena. Some of these highly trained and experienced specialists may have had no other practical choice open to them. Their legal status – slave or free – is uncertain. Under Roman law, a freed gladiator could not "offer such services [as those of a gladiator] after manumission, because they cannot be performed without endangering [his] life." All contracted volunteers, including those of equestrian and senatorial class, were legally enslaved by their ''auctoratio'' because it involved their potentially lethal submission to a master. All ''arenarii'' (those who appeared in the arena) were "''infamia, infames'' by reputation", a form of social dishonour which excluded them from most of the advantages and rights of citizenship. Payment for such appearances compounded their ''infamia''. The legal and social status of even the most popular and wealthy ''auctorati'' was thus marginal at best. They could not vote, plead in court nor leave a will; and unless they were manumitted, their lives and property belonged to their masters. Nevertheless, there is evidence of informal if not entirely lawful practices to the contrary. Some "unfree" gladiators bequeathed money and personal property to wives and children, possibly via a sympathetic owner or ''familia''; some had their own slaves and gave them their freedom. One gladiator was even granted "citizenship" to several Greek cities of the Eastern Roman world.

Caesar's ''munus'' of 46 BC included at least one equestrian, son of a Praetor, and two volunteers of possible senatorial rank. Augustus, who enjoyed watching the games, forbade the participation of senators, equestrians and their descendants as fighters or ''arenarii'', but in 11 AD he bent his own rules and allowed equestrians to volunteer because "the prohibition was no use". Under Tiberius, the Larinum decree (19AD) reiterated Augustus' original prohibitions. Thereafter,

Among the most admired and skilled ''auctorati'' were those who, having been granted manumission, volunteered to fight in the arena. Some of these highly trained and experienced specialists may have had no other practical choice open to them. Their legal status – slave or free – is uncertain. Under Roman law, a freed gladiator could not "offer such services [as those of a gladiator] after manumission, because they cannot be performed without endangering [his] life." All contracted volunteers, including those of equestrian and senatorial class, were legally enslaved by their ''auctoratio'' because it involved their potentially lethal submission to a master. All ''arenarii'' (those who appeared in the arena) were "''infamia, infames'' by reputation", a form of social dishonour which excluded them from most of the advantages and rights of citizenship. Payment for such appearances compounded their ''infamia''. The legal and social status of even the most popular and wealthy ''auctorati'' was thus marginal at best. They could not vote, plead in court nor leave a will; and unless they were manumitted, their lives and property belonged to their masters. Nevertheless, there is evidence of informal if not entirely lawful practices to the contrary. Some "unfree" gladiators bequeathed money and personal property to wives and children, possibly via a sympathetic owner or ''familia''; some had their own slaves and gave them their freedom. One gladiator was even granted "citizenship" to several Greek cities of the Eastern Roman world.

Caesar's ''munus'' of 46 BC included at least one equestrian, son of a Praetor, and two volunteers of possible senatorial rank. Augustus, who enjoyed watching the games, forbade the participation of senators, equestrians and their descendants as fighters or ''arenarii'', but in 11 AD he bent his own rules and allowed equestrians to volunteer because "the prohibition was no use". Under Tiberius, the Larinum decree (19AD) reiterated Augustus' original prohibitions. Thereafter,

The earliest known Roman amphitheatre was built at Pompeii by Sullan colonists, around 70 BC. The first in the city of Rome was the extraordinary wooden amphitheatre of Gaius Scribonius Curio (praetor 49 BC), Gaius Scribonius Curio (built in 53 BC). The first part-stone amphitheatre in Rome was inaugurated in 29–30 BC, in time for the triple triumph of Octavian (later Augustus). Shortly after it burned down in 64 AD, Vespasian began its replacement, later known as the Amphitheatrum Flavium (Colosseum), which seated 50,000 spectators and would remain the largest in the Empire. It was Inaugural games of the Flavian Amphitheatre, inaugurated by

The earliest known Roman amphitheatre was built at Pompeii by Sullan colonists, around 70 BC. The first in the city of Rome was the extraordinary wooden amphitheatre of Gaius Scribonius Curio (praetor 49 BC), Gaius Scribonius Curio (built in 53 BC). The first part-stone amphitheatre in Rome was inaugurated in 29–30 BC, in time for the triple triumph of Octavian (later Augustus). Shortly after it burned down in 64 AD, Vespasian began its replacement, later known as the Amphitheatrum Flavium (Colosseum), which seated 50,000 spectators and would remain the largest in the Empire. It was Inaugural games of the Flavian Amphitheatre, inaugurated by  Amphitheatres were usually oval in plan. Their seating tiers surrounded the arena below, where the community's judgments were meted out, in full public view. From across the stands, crowd and ''editor'' could assess each other's character and temperament. For the crowd, amphitheatres afforded unique opportunities for free expression and free speech (''theatralis licentia''). Petitions could be submitted to the ''editor'' (as magistrate) in full view of the community. ''Factiones'' and claques could vent their spleen on each other, and occasionally on Emperors. The emperor Titus's dignified yet confident ease in his management of an amphitheatre crowd and its factions were taken as a measure of his enormous popularity and the rightness of his imperium. The amphitheatre ''munus'' thus served the Roman community as living theatre and a court in miniature, in which judgement could be served not only on those in the arena below, but on their judges.. Amphitheatres also provided a means of social control. Their seating was "disorderly and indiscriminate" until

Amphitheatres were usually oval in plan. Their seating tiers surrounded the arena below, where the community's judgments were meted out, in full public view. From across the stands, crowd and ''editor'' could assess each other's character and temperament. For the crowd, amphitheatres afforded unique opportunities for free expression and free speech (''theatralis licentia''). Petitions could be submitted to the ''editor'' (as magistrate) in full view of the community. ''Factiones'' and claques could vent their spleen on each other, and occasionally on Emperors. The emperor Titus's dignified yet confident ease in his management of an amphitheatre crowd and its factions were taken as a measure of his enormous popularity and the rightness of his imperium. The amphitheatre ''munus'' thus served the Roman community as living theatre and a court in miniature, in which judgement could be served not only on those in the arena below, but on their judges.. Amphitheatres also provided a means of social control. Their seating was "disorderly and indiscriminate" until

Popular factions supported favourite gladiators and gladiator types. Under Augustan legislation, the Samnite type was renamed ''Secutor'' ("chaser", or "pursuer"). The secutor was equipped with a long, heavy "large" shield called a ''Scutum (shield), scutum''; ''Secutores'', their supporters and any heavyweight ''secutor''-based types such as the Murmillo were ''secutarii''. Lighter types, such as the Thraex, were equipped with a smaller, lighter shield called a ''Parma (shield), parma'', from which they and their supporters were named ''parmularii'' ("small shields"). Titus and Trajan preferred the ''parmularii'' and Domitian the ''secutarii''; Marcus Aurelius took neither side. Nero seems to have enjoyed the brawls between rowdy, enthusiastic and sometimes violent factions, but called in the troops if they went too far..

There were also local rivalries. At Pompeii's amphitheatre, during Nero's reign, the trading of insults between Pompeii, Pompeians and Nucerian spectators during public ''ludi'' led to stone throwing and riot. Many were killed or wounded. Nero banned gladiator ''munera'' (though not the games) at Pompeii for ten years as punishment. The story is told in Pompeian graffiti and high quality wall painting, with much boasting of Pompeii's "victory" over Nuceria.

Popular factions supported favourite gladiators and gladiator types. Under Augustan legislation, the Samnite type was renamed ''Secutor'' ("chaser", or "pursuer"). The secutor was equipped with a long, heavy "large" shield called a ''Scutum (shield), scutum''; ''Secutores'', their supporters and any heavyweight ''secutor''-based types such as the Murmillo were ''secutarii''. Lighter types, such as the Thraex, were equipped with a smaller, lighter shield called a ''Parma (shield), parma'', from which they and their supporters were named ''parmularii'' ("small shields"). Titus and Trajan preferred the ''parmularii'' and Domitian the ''secutarii''; Marcus Aurelius took neither side. Nero seems to have enjoyed the brawls between rowdy, enthusiastic and sometimes violent factions, but called in the troops if they went too far..

There were also local rivalries. At Pompeii's amphitheatre, during Nero's reign, the trading of insults between Pompeii, Pompeians and Nucerian spectators during public ''ludi'' led to stone throwing and riot. Many were killed or wounded. Nero banned gladiator ''munera'' (though not the games) at Pompeii for ten years as punishment. The story is told in Pompeian graffiti and high quality wall painting, with much boasting of Pompeii's "victory" over Nuceria.

The account notes, uncomfortably, the bloodless human sacrifices performed to help turn the tide of the war in Rome's favour. While the Senate mustered their willing slaves, Hannibal offered his dishonoured Roman captives a chance for honourable death, in what Livy describes as something very like the Roman ''munus''. The ''munus'' thus represented an essentially military, self-sacrificial ideal, taken to extreme fulfillment in the gladiator's oath. By the ''devotio'' of a voluntary oath, a slave might achieve the quality of a Roman (''Romanitas''), become the embodiment of true ''virtus'' (manliness, or manly virtue), and paradoxically, be granted ''missio'' while remaining a slave. The gladiator as a specialist fighter, and the ethos and organization of the gladiator schools, would inform the development of the Roman military as the most effective force of its time. In 107 BC, the Gaius Marius, Marian Reforms established the Roman army as a professional body. Two years later, following its defeat at the Battle of Arausio:

The account notes, uncomfortably, the bloodless human sacrifices performed to help turn the tide of the war in Rome's favour. While the Senate mustered their willing slaves, Hannibal offered his dishonoured Roman captives a chance for honourable death, in what Livy describes as something very like the Roman ''munus''. The ''munus'' thus represented an essentially military, self-sacrificial ideal, taken to extreme fulfillment in the gladiator's oath. By the ''devotio'' of a voluntary oath, a slave might achieve the quality of a Roman (''Romanitas''), become the embodiment of true ''virtus'' (manliness, or manly virtue), and paradoxically, be granted ''missio'' while remaining a slave. The gladiator as a specialist fighter, and the ethos and organization of the gladiator schools, would inform the development of the Roman military as the most effective force of its time. In 107 BC, the Gaius Marius, Marian Reforms established the Roman army as a professional body. Two years later, following its defeat at the Battle of Arausio:

File:Brot und Spiele Gladiators1.jpg, Gladiator show fight in Trier in 2005.

File:5791 Arenes NIM 6062 C Recoura.jpg, Nimes, 2005.

File:Provacatores show fight 02.jpg, Carnuntum, Austria, 2007.

File:Villa-borg-2011-gladiatoren1.ogv, Video of a show fight at the Roman Villa Borg, Germany, in 2011 (Retiarius vs. Secutor, Thraex vs. Murmillo).

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

and Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalized, and segregated even in death.

Irrespective of their origin, gladiators offered spectators an example of Rome's martial ethics and, in fighting or dying well, they could inspire admiration and popular acclaim. They were celebrated in high and low art, and their value as entertainers was commemorated in precious and commonplace objects throughout the Roman world.

The origin of gladiatorial combat is open to debate. There is evidence of it in funeral rites during the Punic Wars of the 3rd century BC, and thereafter it rapidly became an essential feature of politics and social life in the Roman world. Its popularity led to its use in ever more lavish and costly games

A game is a structured form of play, usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator sports or games) or art (suc ...

.

The gladiator games lasted for nearly a thousand years, reaching their peak between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD. Christians disapproved of the games because they involved idolatrous pagan rituals, and the popularity of gladatorial contests declined in the fifth century, leading to their disappearance.

History

Origins

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

wrote that they were first held in 310 BC by the Campanians in celebration of their victory over the Samnites. Long after the games had ceased, the 7th century AD writer Isidore of Seville derived Latin '' lanista'' (manager of gladiators) from the Etruscan word for "executioner", and the title of " Charon" (an official who accompanied the dead from the Roman gladiatorial arena) from Charun

In Etruscan mythology, Charun (also spelled Charu, or Karun) acted as one of the psychopompoi of the underworld (not to be confused with the god of the underworld, known to the Etruscans as Aita). He is often portrayed with Vanth, a winged f ...

, psychopomp of the Etruscan underworld. This was accepted and repeated in most early modern, standard histories of the games.

For some modern scholars, reappraisal of pictorial evidence supports a Campanian origin, or at least a borrowing, for the games and gladiators. Campania hosted the earliest known gladiator schools (''ludi

''Ludi'' ( Latin plural) were public games held for the benefit and entertainment of the Roman people (''populus Romanus''). ''Ludi'' were held in conjunction with, or sometimes as the major feature of, Roman religious festivals, and were also ...

''). Tomb frescoes from the Campanian city of Paestum (4th century BC) show paired fighters, with helmets, spears and shields, in a propitiatory funeral blood-rite that anticipates early Roman gladiator games. Compared to these images, supporting evidence from Etruscan tomb-paintings is tentative and late. The Paestum frescoes may represent the continuation of a much older tradition, acquired or inherited from Greek colonists of the 8th century BC.

Livy places the first Roman gladiator games (264 BC) in the early stage of Rome's First Punic War, against Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, when Decimus Junius Brutus Scaeva had three gladiator pairs fight to the death in Rome's "cattle market" forum ('' Forum Boarium'') to honor his dead father, Brutus Pera. Livy describes this as a "''munus''" (plural: '' munera''), a gift, in this case a commemorative duty owed the manes

In ancient Roman religion, the ''Manes'' (, , ) or ''Di Manes'' are chthonic deities sometimes thought to represent souls of deceased loved ones. They were associated with the '' Lares'', '' Lemures,'' '' Genii'', and ''Di Penates'' as deities ( ...

(spirit, or shade) of a dead ancestor by his descendants. The development of the gladiator ''munus'' and its gladiator types was most strongly influenced by Samnium's support for Hannibal and the subsequent punitive expeditions against the Samnites by Rome and its Campanian allies; the earliest, most frequently mentioned and probably most popular type was the Samnite.

The war in Samnium, immediately afterwards, was attended with equal danger and an equally glorious conclusion. The enemy, besides their other warlike preparation, had made their battle-line to glitter with new and splendid arms. There were two corps: the shields of the one were inlaid with gold, of the other with silver ... The Romans had already heard of these splendid accoutrements, but their generals had taught them that a soldier should be rough to look on, not adorned with gold and silver but putting his trust in iron and in courage ... The Dictator, as decreed by the senate, celebrated a triumph, in which by far the finest show was afforded by the captured armour. So the Romans made use of the splendid armour of their enemies to do honour to their gods; while the Campanians, in consequence of their pride and in hatred of the Samnites, equipped after this fashion the gladiators who furnished them entertainment at their feasts, and bestowed on them the name Samnites.Livy's account skirts the funereal, sacrificial function of early Roman gladiator combats and reflects the later theatrical ethos of the Roman gladiator show: splendidly, exotically armed and armoured

barbarians

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be les ...

, treacherous and degenerate, are dominated by Roman iron and native courage. His plain Romans virtuously dedicate the magnificent spoils of war to the gods. Their Campanian allies stage a dinner entertainment using gladiators who may not be Samnites, but play the Samnite role. Other groups and tribes would join the cast list as Roman territories expanded. Most gladiators were armed and armoured in the manner of the enemies of Rome. The gladiator ''munus'' became a morally instructive form of historic enactment in which the only honourable option for the gladiator was to fight well, or else die well.

Development

In 216 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, lateconsul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

and augur, was honoured by his sons with three days of ''gladiatora munera'' in the Forum Romanum, using twenty-two pairs of gladiators. Ten years later, Scipio Africanus gave a commemorative ''munus'' in Iberia for his father and uncle, casualties in the Punic Wars. High status non-Romans, and possibly Romans too, volunteered as his gladiators.. The context of the Punic Wars and Rome's near-disastrous defeat at the Battle of Cannae (216 BC) link these early games to munificence, the celebration of military victory and the religious expiation of military disaster; these ''munera'' appear to serve a morale-raising agenda in an era of military threat and expansion. The next recorded ''munus'', held for the funeral of Publius Licinius in 183 BC, was more extravagant. It involved three days of funeral games, 120 gladiators, and public distribution of meat (''visceratio data'') – a practice that reflected the gladiatorial fights at Campanian banquets described by Livy and later deplored by Silius Italicus.

The enthusiastic adoption of ''gladiatoria munera'' by Rome's Iberian allies shows how easily, and how early, the culture of the gladiator ''munus'' permeated places far from Rome itself. By 174 BC, "small" Roman ''munera'' (private or public), provided by an '' editor'' of relatively low importance, may have been so commonplace and unremarkable they were not considered worth recording:

Many gladiatorial games were given in that year, some unimportant, one noteworthy beyond the rest – that of Titus Flamininus which he gave to commemorate the death of his father, which lasted four days, and was accompanied by a public distribution of meats, a banquet, and scenic performances. The climax of the show which was big for the time was that in three days seventy four gladiators fought.In 105 BC, the ruling consuls offered Rome its first taste of state-sponsored " barbarian combat" demonstrated by gladiators from Capua, as part of a training program for the military. It proved immensely popular.. Wiedemann is citing Valerius Maximus, 2.3.2. Thereafter, the gladiator contests formerly restricted to private ''munera'' were often included in the state games (''

ludi

''Ludi'' ( Latin plural) were public games held for the benefit and entertainment of the Roman people (''populus Romanus''). ''Ludi'' were held in conjunction with, or sometimes as the major feature of, Roman religious festivals, and were also ...

'') that accompanied the major religious festivals. Where traditional ''ludi'' had been dedicated to a deity, such as Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

, the ''munera'' could be dedicated to an aristocratic sponsor's divine or heroic ancestor..

Peak

Gladiatorial games offered their sponsors extravagantly expensive but effective opportunities for self-promotion, and gave their clients and potential voters exciting entertainment at little or no cost to themselves. Gladiators became big business for trainers and owners, for politicians on the make and those who had reached the top and wished to stay there. A politically ambitious '' privatus'' (private citizen) might postpone his deceased father's ''munus'' to the election season, when a generous show might drum up votes; those in power and those seeking it needed the support of the plebeians and their tribunes, whose votes might be won with the mere promise of an exceptionally good show. Sulla, during his term as ''

Gladiatorial games offered their sponsors extravagantly expensive but effective opportunities for self-promotion, and gave their clients and potential voters exciting entertainment at little or no cost to themselves. Gladiators became big business for trainers and owners, for politicians on the make and those who had reached the top and wished to stay there. A politically ambitious '' privatus'' (private citizen) might postpone his deceased father's ''munus'' to the election season, when a generous show might drum up votes; those in power and those seeking it needed the support of the plebeians and their tribunes, whose votes might be won with the mere promise of an exceptionally good show. Sulla, during his term as ''praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

'', showed his usual acumen in breaking his own sumptuary

Sumptuary laws (from Latin ''sūmptuāriae lēgēs'') are laws that try to regulate consumption. ''Black's Law Dictionary'' defines them as "Laws made for the purpose of restraining luxury or extravagance, particularly against inordinate expendit ...

laws to give the most lavish ''munus'' yet seen in Rome, for the funeral of his wife, Metella.

In the closing years of the politically and socially unstable Late Republic, any aristocratic owner of gladiators had political muscle at his disposal. In 65 BC, newly elected '' curule aedile'' Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

held games that he justified as ''munus'' to his father, who had been dead for 20 years. Despite an already enormous personal debt, he used 320 gladiator pairs in silvered armour. He had more available in Capua but the senate, mindful of the recent Spartacus revolt and fearful of Caesar's burgeoning private armies and rising popularity, imposed a limit of 320 pairs as the maximum number of gladiators any citizen could keep in Rome. Caesar's showmanship was unprecedented in scale and expense; he had staged a ''munus'' as memorial rather than funeral rite, eroding any practical or meaningful distinction between ''munus'' and ''ludi''.

Gladiatorial games, usually linked with beast shows, spread throughout the republic and beyond. Anti-corruption laws of 65 and 63 BC attempted but failed to curb the political usefulness of the games to their sponsors. Following Caesar's assassination and the Roman Civil War, Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

assumed imperial authority over the games, including ''munera'', and formalised their provision as a civic and religious duty. His revision of sumptuary law capped private and public expenditure on ''munera'', claiming to save the Roman elite from the bankruptcies they would otherwise suffer, and restricting gladiator ''munera'' to the festivals of Saturnalia and Quinquatria. Henceforth, an imperial praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

's official ''munus'' was allowed a maximum of 120 gladiators at a ceiling cost of 25,000 denarii; an imperial ''ludi'' might cost no less than 180,000 denarii. Throughout the empire, the greatest and most celebrated games would now be identified with the state-sponsored imperial cult, which furthered public recognition, respect and approval for the emperor's divine ''numen

Numen (plural numina) is a Latin term for " divinity", "divine presence", or "divine will." The Latin authors defined it as follows:For a more extensive account, refer to Cicero writes of a "divine mind" (''divina mens''), a god "whose numen ev ...

'', his laws, and his agents. Between 108 and 109 AD, Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

celebrated his Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

n victories using a reported 10,000 gladiators and 11,000 animals over 123 days. The cost of gladiators and ''munera'' continued to spiral out of control. Legislation of 177 AD by Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good E ...

did little to stop it, and was completely ignored by his son, Commodus.

Decline

The decline of the gladiatorial ''munus'' was a far from straightforward process. The crisis of the 3rd century imposed increasing military demands on the imperial purse, from which the Roman Empire never quite recovered, and lesser magistrates found their provision of various obligatory ''munera'' an increasingly unrewarding tax on the doubtful privileges of office. Still, emperors continued to subsidize the games as a matter of undiminished public interest. In the early 3rd century AD, the Christian writerTertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

condemned the attendance of Christians: the combats, he said, were murder, their witnessing spiritually and morally harmful and the gladiator an instrument of pagan human sacrifice. Carolyn Osiek comments:

The reason, we would suppose, would be primarily the bloodthirsty violence, but his is different: the extent of religious ritual and meaning in them, which constitutes idolatry. Although Tertullian states that these events are forbidden to believers, the fact that he writes a whole treatise to convince Christians that they should not attend (''De Spectaculis'') shows that apparently not everyone agreed to stay away from them.In the next century,

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

deplored the youthful fascination of his friend (and later fellow-convert and bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

) Alypius of Thagaste

Alypius of Thagaste was bishop of the see of Tagaste (in what is now Algeria) in 394. He was a lifelong friend of Augustine of Hippo and joined him in his conversion (in 386; ''Confessions'' 8.12.28) and life in Christianity. He is credited with ...

, with the ''munera'' spectacle as inimical to a Christian life and salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

. Amphitheatres continued to host the spectacular administration of Imperial justice: in 315 Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

condemned child-snatchers ''ad bestias

''Damnatio ad bestias'' (Latin for "condemnation to beasts") was a form of Roman capital punishment where the condemned person was killed by wild animals, usually lions or other big cats. This form of execution, which first appeared during the Ro ...

'' in the arena. Ten years later, he forbade criminals being forced to fight to the death as gladiators:

Bloody spectacles do not please us in civil ease and domestic quiet. For that reason we forbid those people to be gladiators who by reason of some criminal act were accustomed to deserve this condition and sentence. You shall rather sentence them to serve in the mines so that they may acknowledge the penalties of their crimes with blood.

This has been interpreted as a ban on gladiatorial combat. Yet, in the last year of his life, Constantine wrote a letter to the citizens of Hispellum, granting its people the right to celebrate his rule with gladiatorial games.

In 365, Valentinian I (r. 364–375) threatened to fine a judge who sentenced Christians to the arena and in 384 attempted, like most of his predecessors, to limit the expenses of ''gladiatora munera''.

In 393,

This has been interpreted as a ban on gladiatorial combat. Yet, in the last year of his life, Constantine wrote a letter to the citizens of Hispellum, granting its people the right to celebrate his rule with gladiatorial games.

In 365, Valentinian I (r. 364–375) threatened to fine a judge who sentenced Christians to the arena and in 384 attempted, like most of his predecessors, to limit the expenses of ''gladiatora munera''.

In 393, Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

(r. 379–395) adopted Nicene

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire and banned pagan festivals. The ''ludi'' continued, very gradually shorn of their stubbornly pagan elements. Honorius (r. 395–423) legally ended gladiator games in 399, and again in 404, at least in the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

. According to Theodoret, the ban was in consequence of Saint Telemachus' martyrdom by spectators at a gladiator ''munus.'' Valentinian III (r. 425–455) repeated the ban in 438, perhaps effectively, though ''venationes'' continued beyond 536. By this time, interest in gladiator contests had waned throughout the Roman world. In the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

Empire, theatrical shows and chariot races continued to attract the crowds, and drew a generous imperial subsidy.

Organisation

The earliest '' munera'' took place at or near the tomb of the deceased and these were organised by their ''munerator'' (who made the offering). Later games were held by an ''editor'', either identical with the ''munerator'' or an official employed by him. As time passed, these titles and meanings may have merged.. In the republican era, private citizens could own and train gladiators, or lease them from a ''lanista'' (owner of a gladiator training school). From the ''principate'' onwards, private citizens could hold ''munera'' and own gladiators only with imperial permission, and the role of ''editor'' was increasingly tied to state officialdom. Legislation byClaudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Drusus and Antonia Minor ...

required that ''quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

s'', the lowest rank of Roman magistrate, personally subsidise two-thirds of the costs of games for their small-town communities – in effect, both an advertisement of their personal generosity and a part-purchase of their office. Bigger games were put on by senior magistrates, who could better afford them. The largest and most lavish of all were paid for by the emperor himself..

The gladiators

The earliest types of gladiator were named after Rome's enemies of that time: the Samnite,

The earliest types of gladiator were named after Rome's enemies of that time: the Samnite, Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

and Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. The Samnite, heavily armed, elegantly helmed and probably the most popular type, was renamed secutor and the Gaul renamed murmillo, once these former enemies had been conquered then absorbed into Rome's Empire. In the mid-republican ''munus'', each type seems to have fought against a similar or identical type. In the later Republic and early Empire, various "fantasy" types were introduced, and were set against dissimilar but complementary types. For example, the bareheaded, nimble retiarius ("net-man"), armoured only at the left arm and shoulder, pitted his net, trident and dagger against the more heavily armoured, helmeted Secutor. Most depictions of gladiators show the most common and popular types. Passing literary references to others has allowed their tentative reconstruction. Other novelties introduced around this time included gladiators who fought from chariots or carts, or from horseback. At an unknown date, cestus fighters were introduced to Roman arenas, probably from Greece, armed with potentially lethal boxing gloves.

The trade in gladiators was empire-wide, and subjected to official supervision. Rome's military success produced a supply of soldier-prisoners who were redistributed for use in State mines or amphitheatres and for sale on the open market. For example, in the aftermath of the Jewish Revolt, the gladiator schools received an influx of Jews – those rejected for training would have been sent straight to the arenas as ''noxii'' (lit. "hurtful ones"). The best – the most robust – were sent to Rome. In Rome's military ethos, enemy soldiers who had surrendered or allowed their own capture and enslavement had been granted an unmerited gift of life. Their training as gladiators would give them opportunity to redeem their honour in the ''munus''.

Two other sources of gladiators, found increasingly during the Principate and the relatively low military activity of the

Two other sources of gladiators, found increasingly during the Principate and the relatively low military activity of the Pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is identified as a period and as a golden age of increased as well as sustained Roman imperialism, relative peace and order, prosperous stabilit ...

, were slaves condemned to the arena (''damnati''), to gladiator schools or games (''ad ludum gladiatorium'') as punishment for crimes, and the paid volunteers ('' auctorati'') who by the late Republic may have comprised approximately half – and possibly the most capable half – of all gladiators. The use of volunteers had a precedent in the Iberian ''munus'' of Scipio Africanus; but none of those had been paid.

For the poor, and for non-citizens, enrollment in a gladiator school offered a trade, regular food, housing of sorts and a fighting chance of fame and fortune. Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the au ...

chose a troupe of gladiators to be his personal bodyguard.. Futrell is citing Cassius Dio. Gladiators customarily kept their prize money and any gifts they received, and these could be substantial. Tiberius offered several retired gladiators 100,000 ''sesterces'' each to return to the arena. Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

gave the gladiator Spiculus property and residence "equal to those of men who had celebrated triumphs."

Women

From the 60s AD female gladiators appear as rare and "exotic markers of exceptionally lavish spectacle".. In 66 AD,Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

had Ethiopian women, men and children fight at a ''munus'' to impress the King Tiridates I of Armenia. Romans seem to have found the idea of a female gladiator novel and entertaining, or downright absurd; Juvenal titillates his readers with a woman named "Mevia", hunting boars in the arena "with spear in hand and breasts exposed", and Petronius mocks the pretensions of a rich, low-class citizen, whose ''munus'' includes a woman fighting from a cart or chariot. A ''munus'' of 89 AD, during Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Fl ...

's reign, featured a battle between female gladiators, described as "Amazons". In Halicarnassus, a 2nd-century AD relief depicts two female combatants named "Amazon" and "Achillia"; their match ended in a draw.; . In the same century, an epigraph praises one of Ostia's local elite as the first to "arm women" in the history of its games. Female gladiators probably submitted to the same regulations and training as their male counterparts. Roman morality required that all gladiators be of the lowest social classes, and emperors who failed to respect this distinction earned the scorn of posterity. Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

takes pains to point out that when the much admired emperor Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a mili ...

used female gladiators, they were of acceptably low class.

Some regarded female gladiators of any type or class as a symptom of corrupted Roman appetites, morals and womanhood. Before he became emperor, Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary suc ...

may have attended the Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

ene Olympic Games, which had been revived by the emperor Commodus and included traditional Greek female athletics. Septimius' attempt to give Rome a similarly dignified display of female athletics was met by the crowd with ribald chants and cat-calls. Probably as a result, he banned the use of female gladiators in 200 AD.

Emperors

Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germani ...

, Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a mili ...

, Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

, Lucius Verus, Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor ...

, Geta and Didius Julianus

Marcus Didius Julianus (; 29 January 133 or 137 – 2 June 193) was Roman emperor for nine weeks from March to June 193, during the Year of the Five Emperors. Julianus had a promising political career, governing several provinces, including D ...

were all said to have performed in the arena, either in public or private, but risks to themselves were minimal. Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Drusus and Antonia Minor ...

, characterised by his historians as morbidly cruel and boorish, fought a whale trapped in the harbor in front of a group of spectators. Commentators invariably disapproved of such performances.

Commodus was a fanatical participant at the ''ludi'', and compelled Rome's elite to attend his performances as gladiator, ''bestiarius

Among Ancient Romans, ''bestiarii'' (singular ''bestiarius'') were those who went into combat with beasts, or were exposed to them. It is conventional

'' or '' venator''. Most of his performances as a gladiator were bloodless affairs, fought with wooden swords; he invariably won. He was said to have restyled Nero's colossal statue in his own image as "Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the ...

Reborn", dedicated to himself as "Champion of ''secutores''; only left-handed fighter to conquer twelve times one thousand men." He was said to have killed 100 lions in one day, almost certainly from an elevated platform surrounding the arena perimeter, which allowed him to safely demonstrate his marksmanship. On another occasion, he decapitated a running ostrich with a specially designed dart, carried the bloodied head and his sword over to the Senatorial seats and gesticulated as though they were next. As reward for these services, he drew a gigantic stipend from the public purse.

The games

Preparations

Gladiator games were advertised well beforehand, on billboards that gave the reason for the game, its editor, venue, date and the number of paired gladiators (''ordinarii'') to be used. Other highlighted features could include details of ''venationes'', executions, music and any luxuries to be provided for the spectators, such as an awning against the sun, water sprinklers, food, drink, sweets and occasionally "door prizes". For enthusiasts and gamblers, a more detailed program (''libellus'') was distributed on the day of the ''munus'', showing the names, types and match records of gladiator pairs, and their order of appearance. Left-handed gladiators were advertised as a rarity; they were trained to fight right-handers, which gave them an advantage over most opponents and produced an interestingly unorthodox combination.

The night before the ''munus'', the gladiators were given a banquet and opportunity to order their personal and private affairs; Futrell notes its similarity to a ritualistic or sacramental "last meal". These were probably both family and public events which included even the ''noxii'', sentenced to die in the arena the following day; and the ''damnati'', who would have at least a slender chance of survival. The event may also have been used to drum up more publicity for the imminent game..

Gladiator games were advertised well beforehand, on billboards that gave the reason for the game, its editor, venue, date and the number of paired gladiators (''ordinarii'') to be used. Other highlighted features could include details of ''venationes'', executions, music and any luxuries to be provided for the spectators, such as an awning against the sun, water sprinklers, food, drink, sweets and occasionally "door prizes". For enthusiasts and gamblers, a more detailed program (''libellus'') was distributed on the day of the ''munus'', showing the names, types and match records of gladiator pairs, and their order of appearance. Left-handed gladiators were advertised as a rarity; they were trained to fight right-handers, which gave them an advantage over most opponents and produced an interestingly unorthodox combination.

The night before the ''munus'', the gladiators were given a banquet and opportunity to order their personal and private affairs; Futrell notes its similarity to a ritualistic or sacramental "last meal". These were probably both family and public events which included even the ''noxii'', sentenced to die in the arena the following day; and the ''damnati'', who would have at least a slender chance of survival. The event may also have been used to drum up more publicity for the imminent game..

The ''ludi'' and ''munus''

Official ''munera'' of the early Imperial era seem to have followed a standard form (''munus legitimum''). A procession (''pompa'') entered the arena, led by lictors who bore the fasces that signified the magistrate-''editors power over life and death. They were followed by a small band of trumpeters (''tubicines'') playing a fanfare. Images of the gods were carried in to "witness" the proceedings, followed by a scribe to record the outcome, and a man carrying the palm branch used to honour victors. The magistrate ''editor'' entered among a retinue who carried the arms and armour to be used; the gladiators presumably came in last. The entertainments often began with ''venationes'' (beast hunts) and ''bestiarii'' (beast fighters). Next came the ''ludi meridiani'', which were of variable content but usually involved executions of ''noxii'', some of whom were condemned to be subjects of fatal re-enactments, based on Greek or Roman myths. Gladiators may have been involved in these as executioners, though most of the crowd, and the gladiators themselves, preferred the "dignity" of an even contest. There were also comedy fights; some may have been lethal. A crude Pompeian graffito suggests a burlesque of musicians, dressed as animals named ''Ursus tibicen'' (flute-playing bear) and ''Pullus cornicen'' (horn-blowing chicken), perhaps as accompaniment to clowning by '' paegniarii'' during a "mock" contest of the ''ludi meridiani''.

The entertainments often began with ''venationes'' (beast hunts) and ''bestiarii'' (beast fighters). Next came the ''ludi meridiani'', which were of variable content but usually involved executions of ''noxii'', some of whom were condemned to be subjects of fatal re-enactments, based on Greek or Roman myths. Gladiators may have been involved in these as executioners, though most of the crowd, and the gladiators themselves, preferred the "dignity" of an even contest. There were also comedy fights; some may have been lethal. A crude Pompeian graffito suggests a burlesque of musicians, dressed as animals named ''Ursus tibicen'' (flute-playing bear) and ''Pullus cornicen'' (horn-blowing chicken), perhaps as accompaniment to clowning by '' paegniarii'' during a "mock" contest of the ''ludi meridiani''.

Armatures

The gladiators may have held informal warm-up matches, using blunted or dummy weapons – some ''munera'', however, may have used blunted weapons throughout. The ''editor,'' his representative or an honoured guest would check the weapons (''probatio armorum'') for the scheduled matches. These were the highlight of the day, and were as inventive, varied and novel as the ''editor'' could afford. Armatures could be very costly – some were flamboyantly decorated with exotic feathers, jewels and precious metals. Increasingly the ''munus'' was the ''editors gift to spectators who had come to expect the best as their due.Greek Mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

Image:Antica roma, elmo con cresta, I-III secolo ca.jpg, Helmet from 1st–3rd century

Image:Ornate pair of gladiator shin guards depicting a procession of Bacchus from the gladiator barracks in Pompeii 01.jpg, Ornate gladiator shin guards from Pompeii

Image:Gladiator shin guard depicting the goddess Athena from the gladiator barracks in Pompeii 1st century CE.jpg, Shin guard depicting the goddess Athena

Image:Gladiator shin guard depicting Venus Euploia protectress of seafarers sitting on a ship shaped like a dolphin from Pompeii 1st century CE.jpg, Shin guard depicting Venus Euploia (Venus of the "fair voyage") on a ship shaped like a dolphin

Image:Heart-shaped spear head found in the gladiator barracks in Pompeii 1st century CE.jpg, Heart-shaped spear head found in the gladiator barracks in Pompeii

Combat

Lightly armed and armoured fighters, such as the retiarius, would tire less rapidly than their heavily armed opponents; most bouts would have lasted 10 to 15 minutes, or 20 minutes at most. In late Republican ''munera'', between 10 and 13 matches could have been fought on one day; this assumes one match at a time in the course of an afternoon. Spectators preferred to watch highly skilled, well matched ''ordinarii'' with complementary fighting styles; these were the most costly to train and to hire. A general '' melee'' of several, lower-skilled gladiators was far less costly, but also less popular. Even among the ''ordinarii'', match winners might have to fight a new, well-rested opponent, either a ''tertiarius'' ("third choice gladiator") by prearrangement; or a "substitute" gladiator (''suppositicius'') who fought at the whim of the ''editor'' as an unadvertised, unexpected "extra". This yielded two combats for the cost of three gladiators, rather than four; such contests were prolonged, and in some cases, more bloody. Most were probably of poor quality, but the emperorCaracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor ...

chose to test a notably skilled and successful fighter named Bato against first one ''supposicitius'', whom he beat, and then another, who killed him.Dunkle, Roger, ''Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome'', Routledge, 2013, pp. 70–71 At the opposite level of the profession, a gladiator reluctant to confront his opponent might be whipped, or goaded with hot irons, until he engaged through sheer desperation.

Combats between experienced, well trained gladiators demonstrated a considerable degree of stagecraft. Among the cognoscenti, bravado and skill in combat were esteemed over mere hacking and bloodshed; some gladiators made their careers and reputation from bloodless victories. Suetonius describes an exceptional ''munus'' by Nero, in which no-one was killed, "not even ''noxii'' (enemies of the state)." Fagan speculates that Nero was perversely defying the crowd's expectations, or perhaps trying to please a different kind of crowd.

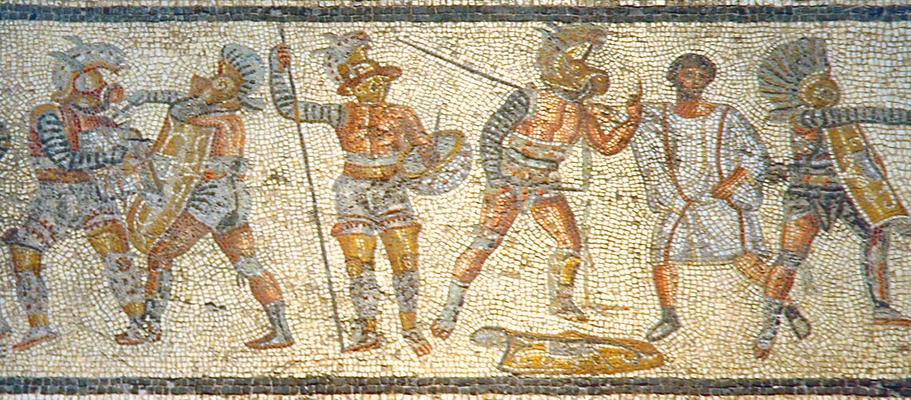

Trained gladiators were expected to observe professional rules of combat. Most matches employed a senior referee (''summa rudis'') and an assistant, shown in mosaics with long staffs (''rudes'') to caution or separate opponents at some crucial point in the match. Referees were usually retired gladiators whose decisions, judgement and discretion were, for the most part, respected; they could stop bouts entirely, or pause them to allow the combatants rest, refreshment and a rub-down.

Ludi and ''munera'' were accompanied by music, played as interludes, or building to a "frenzied crescendo" during combats, perhaps to heighten the suspense during a gladiator's appeal; blows may have been accompanied by trumpet-blasts. The Zliten mosaic in Libya (circa 80–100 AD) shows musicians playing an accompaniment to provincial games (with gladiators, ''bestiarii'', or ''venatores'' and prisoners attacked by beasts). Their instruments are a long straight trumpet ('' tubicen''), a large curved horn ('' Cornu'') and a water organ (''hydraulis''). Similar representations (musicians, gladiators and ''bestiari'') are found on a tomb relief in Pompeii.

Combats between experienced, well trained gladiators demonstrated a considerable degree of stagecraft. Among the cognoscenti, bravado and skill in combat were esteemed over mere hacking and bloodshed; some gladiators made their careers and reputation from bloodless victories. Suetonius describes an exceptional ''munus'' by Nero, in which no-one was killed, "not even ''noxii'' (enemies of the state)." Fagan speculates that Nero was perversely defying the crowd's expectations, or perhaps trying to please a different kind of crowd.

Trained gladiators were expected to observe professional rules of combat. Most matches employed a senior referee (''summa rudis'') and an assistant, shown in mosaics with long staffs (''rudes'') to caution or separate opponents at some crucial point in the match. Referees were usually retired gladiators whose decisions, judgement and discretion were, for the most part, respected; they could stop bouts entirely, or pause them to allow the combatants rest, refreshment and a rub-down.

Ludi and ''munera'' were accompanied by music, played as interludes, or building to a "frenzied crescendo" during combats, perhaps to heighten the suspense during a gladiator's appeal; blows may have been accompanied by trumpet-blasts. The Zliten mosaic in Libya (circa 80–100 AD) shows musicians playing an accompaniment to provincial games (with gladiators, ''bestiarii'', or ''venatores'' and prisoners attacked by beasts). Their instruments are a long straight trumpet ('' tubicen''), a large curved horn ('' Cornu'') and a water organ (''hydraulis''). Similar representations (musicians, gladiators and ''bestiari'') are found on a tomb relief in Pompeii.

Victory and defeat

A match was won by the gladiator who overcame his opponent, or killed him outright. Victors received the palm branch and an award from the ''editor''. An outstanding fighter might receive a laurel crown and money from an appreciative crowd but for anyone originally condemned ''ad ludum'' the greatest reward was manumission (emancipation), symbolised by the gift of a wooden training sword or staff (''rudis'') from the ''editor''. Martial describes a match betweenPriscus

Priscus of Panium (; el, Πρίσκος; 410s AD/420s AD-after 472 AD) was a 5th-century Eastern Roman diplomat and Greek historian and rhetorician (or sophist)...: "For information about Attila, his court and the organization of life genera ...

and Verus, who fought so evenly and bravely for so long that when both acknowledged defeat at the same instant, Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a mili ...

awarded victory and a ''rudis'' to each. Flamma was awarded the ''rudis'' four times, but chose to remain a gladiator. His gravestone in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

includes his record: "Flamma, '' secutor'', lived 30 years, fought 34 times, won 21 times, fought to a draw 9 times, defeated 4 times, a Syrian by nationality. Delicatus made this for his deserving comrade-in-arms."

A gladiator could acknowledge defeat by raising a finger (''ad digitum''), in appeal to the referee to stop the combat and refer to the ''editor'', whose decision would usually rest on the crowd's response. In the earliest ''munera'', death was considered a righteous penalty for defeat; later, those who fought well might be granted remission at the whim of the crowd or the ''editor''. During the Imperial era, matches advertised as ''sine missione'' (usually understood to mean "without reprieve" for the defeated) suggest that ''missio'' (the sparing of a defeated gladiator's life) had become common practice. The contract between ''editor'' and his ''lanista'' could include compensation for unexpected deaths; this could be "some fifty times higher than the lease price" of the gladiator.

Under Augustus' rule, the demand for gladiators began to exceed supply, and matches ''sine missione'' were officially banned; an economical, pragmatic development that happened to match popular notions of "natural justice". When Caligula and Claudius refused to spare defeated but popular fighters, their own popularity suffered. In general, gladiators who fought well were likely to survive. At a Pompeian match between chariot-fighters, Publius Ostorius, with previous 51 wins to his credit, was granted missio after losing to Scylax, with 26 victories. By common custom, the spectators decided whether or not a losing gladiator should be spared, and chose the winner in the rare event of a standing tie. Even more rarely, perhaps uniquely, one stalemate ended in the killing of one gladiator by the ''editor'' himself. (subscription required) In any event, the final decision of death or life belonged to the ''editor'', who signalled his choice with a gesture described by Roman sources as ''pollice verso'' meaning "with a turned thumb"; a description too imprecise for reconstruction of the gesture or its symbolism. Whether victorious or defeated, a gladiator was bound by oath to accept or implement his editor's decision, "the victor being nothing but the instrument of his [editor's] will." Not all ''editors'' chose to go with the crowd, and not all those condemned to death for putting on a poor show chose to submit:

Once a band of five ''retiarius, retiarii'' in tunics, matched against the same number of ''secutores'', yielded without a struggle; but when their death was ordered, one of them caught up his trident and slew all the victors.Caligula Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germani ...bewailed this in a public proclamation as a most cruel murder.

Death and disposal

A gladiator who was refused ''missio'' was despatched by his opponent. To die well, a gladiator should never ask for mercy, nor cry out. A "good death" redeemed the gladiator from the dishonourable weakness and passivity of defeat, and provided a noble example to those who watched:For death, when it stands near us, gives even to inexperienced men the courage not to seek to avoid the inevitable. So the gladiator, no matter how faint-hearted he has been throughout the fight, offers his throat to his opponent and directs the wavering blade to the vital spot. (Seneca. ''Epistles'', 30.8)Some mosaics show defeated gladiators kneeling in preparation for the moment of death. Seneca's "vital spot" seems to have meant the neck. Gladiator remains from Ephesus confirm this.

The body of a gladiator who had died well was placed on a couch of Libitina and removed with dignity to the arena morgue, where the corpse was stripped of armour, and probably had its throat cut as confirmation of death. The Christian author

The body of a gladiator who had died well was placed on a couch of Libitina and removed with dignity to the arena morgue, where the corpse was stripped of armour, and probably had its throat cut as confirmation of death. The Christian author Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

, commenting on ''ludi meridiani'' in Roman Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

during the peak era of the games, describes a more humiliating method of removal. One arena official, dressed as the "brother of Jove", Dis Pater (god of the underworld) strikes the corpse with a mallet. Another, dressed as Mercury (mythology), Mercury, tests for life-signs with a heated "wand"; once confirmed as dead, the body is dragged from the arena.