Giuseppe Garibaldi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

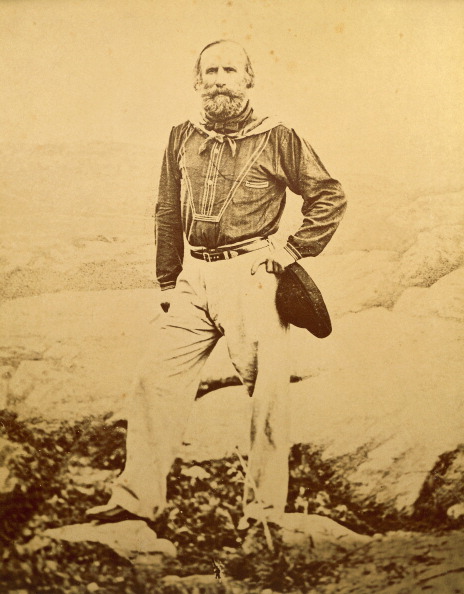

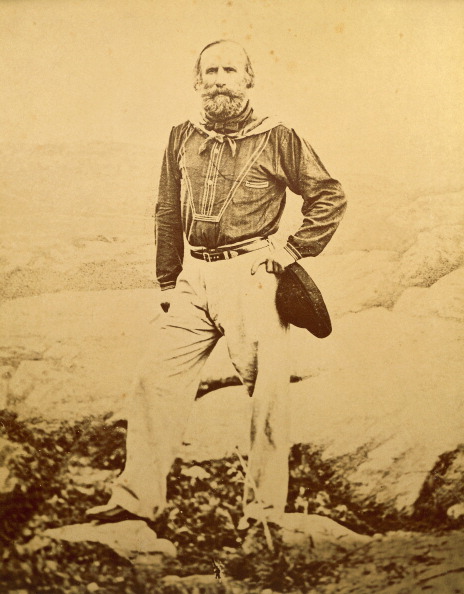

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patriot,

''LeCitazioni''. Retrieved 2 September 2020. "È il più generoso dei pirati che abbia mai incontrato." Francesco de Sanctis,

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in

Garibaldi first sailed to the

Garibaldi first sailed to the  Garibaldi aligned his forces with the Uruguayan Colorados led by Fructuoso Rivera and Joaquín Suárez, who were aligned with the Argentine Unitarian Party. This faction received some support from the French and British in their struggle against the forces of former Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe's Blancos, which was also aligned with Argentine Federales under the rule of

Garibaldi aligned his forces with the Uruguayan Colorados led by Fructuoso Rivera and Joaquín Suárez, who were aligned with the Argentine Unitarian Party. This faction received some support from the French and British in their struggle against the forces of former Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe's Blancos, which was also aligned with Argentine Federales under the rule of

Translated from Giuseppe Garibaldi Massone by the Grand Orient of Italy

/ref> Garibaldi regularized his position later in 1844, joining the lodge Les Amis de la Patrie of

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states and was one of the founders and leaders of the Action Party. Garibaldi offered his services to

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states and was one of the founders and leaders of the Action Party. Garibaldi offered his services to  On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the Apennine mountains. Garibaldi, having entered the chamber covered in blood, made a speech favouring the third option, ending with: ''Ovunque noi saremo, sarà Roma.'' (Wherever we will go, that will be Rome).

The sides negotiated a truce on 1–2 July, Garibaldi withdrew from Rome with 4,000 troops, and an ambition to rouse popular rebellion against the Austrians in central Italy. The French Army entered Rome on 3 July and reestablished the

On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the Apennine mountains. Garibaldi, having entered the chamber covered in blood, made a speech favouring the third option, ending with: ''Ovunque noi saremo, sarà Roma.'' (Wherever we will go, that will be Rome).

The sides negotiated a truce on 1–2 July, Garibaldi withdrew from Rome with 4,000 troops, and an ambition to rouse popular rebellion against the Austrians in central Italy. The French Army entered Rome on 3 July and reestablished the

The ship was to be purchased in the United States. Garibaldi went to New York, arriving on 30 July 1850. However, the funds for buying a ship were lacking. While in New York, he stayed with various Italian friends, including some exiled revolutionaries. He attended the Masonic lodges of New York in 1850, where he met several supporters of democratic internationalism, whose minds were open to socialist thought, and to giving Freemasonry a strong anti-papal stance.

The inventor Antonio Meucci employed Garibaldi in his candle factory on

The ship was to be purchased in the United States. Garibaldi went to New York, arriving on 30 July 1850. However, the funds for buying a ship were lacking. While in New York, he stayed with various Italian friends, including some exiled revolutionaries. He attended the Masonic lodges of New York in 1850, where he met several supporters of democratic internationalism, whose minds were open to socialist thought, and to giving Freemasonry a strong anti-papal stance.

The inventor Antonio Meucci employed Garibaldi in his candle factory on

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in  Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 on the hill of

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 on the hill of  By conquering Palermo, Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island, winning a ferocious and difficult battle at Milazzo. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted.

By conquering Palermo, Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island, winning a ferocious and difficult battle at Milazzo. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted.

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina and marched north. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on 7 September he entered the capital city of

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina and marched north. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on 7 September he entered the capital city of

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and '' realpolitik'', but he also bore a personal grudge for Cavour's trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he supported the Sardinian monarch,

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and '' realpolitik'', but he also bore a personal grudge for Cavour's trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he supported the Sardinian monarch,

– The Civil War Society's "Encyclopedia of the Civil War" – Italian-Americans in the Civil War. Garibaldi expressed interest in aiding the Union, and he was offered a major general's commission in the U.S. Army through a letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to Henry S. Sanford, the U.S. Minister at Brussels, 27 July 1861. On 9 September 1861, Sanford met with Garibaldi and reported the result of the meeting to Seward: This meeting occurred a year before Lincoln was ready to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Sanford's mission was hopeless, and Garibaldi did not join the Union army. A historian of the

Garibaldi himself was intensely anti-Catholic and anti-papal. His efforts to overthrow the Pope by military action mobilized anti-Catholic support. There were major anti-Catholic riots in his name across Britain in 1862, with the Irish Catholics fighting in defense of their Church. Garibaldi's hostility to the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French Emperor

Garibaldi himself was intensely anti-Catholic and anti-papal. His efforts to overthrow the Pope by military action mobilized anti-Catholic support. There were major anti-Catholic riots in his name across Britain in 1862, with the Irish Catholics fighting in defense of their Church. Garibaldi's hostility to the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French Emperor  In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa to Palermo to gather volunteers for the impending campaign, under the slogan ''Roma o Morte'' (Rome or Death). An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. He arrived with a force of around two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from

In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa to Palermo to gather volunteers for the impending campaign, under the slogan ''Roma o Morte'' (Rome or Death). An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. He arrived with a force of around two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from  Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged

Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The  The Italian regular forces were defeated at Lissa on the sea, and made little progress on land after the disaster of Custoza. The sides signed an armistice by which Austria ceded Venetia to Italy, but this result was largely due to Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought, and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. Garibaldi answered with a short telegram from the main square of Bezzecca with the famous motto: ''Obbedisco!'' ("I obey!").

After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly armed volunteers. He was shot in the leg in the

The Italian regular forces were defeated at Lissa on the sea, and made little progress on land after the disaster of Custoza. The sides signed an armistice by which Austria ceded Venetia to Italy, but this result was largely due to Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought, and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. Garibaldi answered with a short telegram from the main square of Bezzecca with the famous motto: ''Obbedisco!'' ("I obey!").

After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly armed volunteers. He was shot in the leg in the  In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the

Garibaldi had long claimed an interest in a vague ethical socialism such as that advanced by

Garibaldi had long claimed an interest in a vague ethical socialism such as that advanced by

Garibaldi's popularity, skill at rousing the common people and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible. He also served as a global exemplar of mid-19th century revolutionary

Garibaldi's popularity, skill at rousing the common people and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible. He also served as a global exemplar of mid-19th century revolutionary  Garibaldi was a popular hero in Britain. In his review of Lucy Riall's Garibaldi biography for ''

Garibaldi was a popular hero in Britain. In his review of Lucy Riall's Garibaldi biography for '' Along with Giuseppe Mazzini and other Europeans, Garibaldi supported the creation of a European federation. Many Europeans expected that the 1871 unification of Germany would make Germany a European and world leader that would champion humanitarian policies. This idea is apparent in the following letter Garibaldi sent to

Along with Giuseppe Mazzini and other Europeans, Garibaldi supported the creation of a European federation. Many Europeans expected that the 1871 unification of Germany would make Germany a European and world leader that would champion humanitarian policies. This idea is apparent in the following letter Garibaldi sent to

Five ships of the

Five ships of the  In 1865, English football team Nottingham Forest chose their home colours from the uniform worn by Garibaldi and his men in 1865."History of Nottingham Forest"

In 1865, English football team Nottingham Forest chose their home colours from the uniform worn by Garibaldi and his men in 1865."History of Nottingham Forest"

Nottingham Forest. Retrieved 18 April 2018. A school in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire was also named after him. The Giuseppe Garibaldi Trophy ( it, Trofeo Garibaldi; french: Trophée Garibaldi) is a The Garibaldi biscuit was named after him, as was a style of beard.

The Garibaldi biscuit was named after him, as was a style of beard.

Gay, H. Nelson, "Lincoln's Offer of a Command to Garibaldi: Light on a Disputed Point of History," ''The Century Magazine'' LXXV (Nov. 1907): 66

* Christopher Hibbert, Hibbert, Christopher. ''Garibaldi and His Enemies: The Clash of Arms and Personalities in the Making of Italy'' (1965), a standard biography. * pp. 332–416.

Mack Smith, Denis, ed. ''Garibaldi'' (Great Lives Observed), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

(primary and secondary sources) * Denis Mack Smith, Mack Smith, Denis. "Giuseppe Garibaldi: 1807-1882". ''History Today'' (March 1956) 5 #3 pp. 188–196. * Mack Smith, Denis. ''Garibaldi: A Great Life in Brief'' (1956

online

Marraro, Howard R. "Lincoln's Offer of a Command to Garibaldi: Further Light on a Disputed Point of History." ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society'' 36 #3 (Sept. 1943): 237–270

* Tim Parks, Parks, Tim. ''The Hero's Way: Walking With Garibaldi From Rome to Ravenna'' (W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2021), travelogue in which Parks and his partner retrace Garibaldi and the Garibaldini's 1849 march * Lucy Riall, Riall, Lucy. ''The Italian Risorgimento: State, Society, and National Unification'' (Routledge, 1994

online

* Riall, Lucy. ''Garibaldi: Invention of a Hero'' (Yale UP, 2007). * Riall, Lucy. "Hero, saint or revolutionary? Nineteenth-century politics and the cult of Garibaldi." ''Modern Italy'' 3.02 (1998): 191–204. * Riall, Lucy. "Travel, migration, exile: Garibaldi's global fame." ''Modern Italy'' 19.1 (2014): 41–52. * Jasper Ridley, Ridley, Jasper. ''Garibaldi'' (1974), a standard biograph

online

* * *

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

and republican. He contributed to Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. He is considered one of the greatest generals of modern times and one of Italy's " fathers of the fatherland", along with Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy and Giuseppe Mazzini. Garibaldi is also known as the "''Hero of the Two Worlds''" because of his military enterprises in South America and Europe.

Garibaldi was a follower of the Italian nationalist Mazzini and embraced the republican nationalism of the Young Italy movement. He became a supporter of Italian unification under a democratic republic

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two exceedingly similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democr ...

an government. However, breaking with Mazzini, he pragmatically allied himself with the monarchist Cavour and Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

in the struggle for independence, subordinating his republican ideals to his nationalist ones until Italy was unified. After participating in an uprising in Piedmont, he was sentenced to death, but escaped and sailed to South America, where he spent 14 years in exile, during which he took part in several wars and learned the art of guerrilla warfare. In 1835 he joined the rebels known as the Ragamuffins (), in the Ragamuffin War in Brazil, and took up their cause of establishing the Riograndense Republic

The Riograndense Republic, often called the Piratini Republic ( pt, República Rio-Grandense or ), was a ''de facto'' state that seceded from the Empire of Brazil and roughly coincided with the present state of Rio Grande do Sul. It was proc ...

and later the Catarinense Republic. Garibaldi also became involved in the Uruguayan Civil War, raising an Italian force known as Redshirts, and is still celebrated as an important contributor to Uruguay's reconstitution.

In 1848, Garibaldi returned to Italy and commanded and fought in military campaigns that eventually led to Italian unification. The provisional government of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

made him a general and the Minister of War promoted him to General of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

in 1849. When the war of independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List of ...

broke out in April 1859, he led his Hunters of the Alps

The Hunters of the Alps ( it, Cacciatori delle Alpi) were a military corps created by Giuseppe Garibaldi in Cuneo on 20 February 1859 to help the regular Sardinian army to free the northern part of Italy in the Second Italian War of Independe ...

in the capture of major cities in Lombardy, including Varese

Varese ( , , or ; lmo, label=Varesino, Varés ; la, Baretium; archaic german: Väris) is a city and ''comune'' in north-western Lombardy, northern Italy, north-west of Milan. The population of Varese in 2018 has reached 80,559.

It is the ca ...

and Como

Como (, ; lmo, Còmm, label= Comasco , or ; lat, Novum Comum; rm, Com; french: Côme) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy. It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como.

Its proximity to Lake Como and to the Alps ...

, and reached the frontier of South Tyrol; the war ended with the acquisition of Lombardy. The following year, he led the Expedition of the Thousand on behalf of and with the consent of Victor Emmanuel II. The expedition was a success and concluded with the annexation of Sicily, Southern Italy, Marche and Umbria to the Kingdom of Sardinia before the creation of a unified Kingdom of Italy on 17 March 1861. His last military campaign took place during the Franco-Prussian War as commander of the Army of the Vosges

The Army of the Vosges (french: Armée des Vosges) was a volunteer force placed under the command of Giuseppe Garibaldi, formed in order to ensure the defense of the road to Lyon from the Prussian Army during the Franco-Prussian war.

Background ...

.

Garibaldi became an international figurehead for national independence and republican ideals, and is considered by the twentieth-century historiography and popular culture as Italy's greatest national hero. He was showered with admiration and praise by many contemporary intellectuals and political figures, including Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

,Mack Smith, ed., Denis (1969). ''Garibaldi'' (Great Lives Observed). Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs. pp. 69–70. . William Brown,"Frasi di William Brown (ammiraglio)"''LeCitazioni''. Retrieved 2 September 2020. "È il più generoso dei pirati che abbia mai incontrato." Francesco de Sanctis,

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Alexandre Dumas, Malwida von Meysenbug, George Sand, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

, and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Jawaharlal Nehru Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat— * * * * and author who was a central figure in India du ...

or '' Jawaharlal Nehru Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat— * * * * and author who was a central figure in India du ...

Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

.Di Mino, Massimiliano; Di Mino, Pier Paolo (2011). ''Il libretto rosso di Garibaldi''. Rome: Castelvecchi Editore. p. 7. . Historian A. J. P. Taylor called him "the only wholly admirable figure in modern history". In the popular telling of his story, he is associated with the red shirts that his volunteers, the ''Garibaldini'', wore in lieu of a uniform.

Early life

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

as . on 4 July 1807 in Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative ...

, which had been conquered by the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

in 1792, to the Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

n family of Domenico Garibaldi from Chiavari

Chiavari (; lij, Ciävai ) is a comune (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, in Italy. It has about 28,000 inhabitants. It is situated near the river Entella.

History

Pre-Roman and Roman Era

A pre-Roman necropolis, which dates ...

and Maria Rosa Nicoletta Raimondi from Loano. In 1814, the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon ...

returned Nice to Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia

Victor Emmanuel I (Vittorio Emanuele; 24 July 1759 – 10 January 1824) was the Duke of Savoy and King of Sardinia (1802–1821).

Biography

Victor Emmanuel was the second son of King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia and Maria Antonia Ferdinanda ...

; nevertheless, France re-annexed it in 1860 by the Treaty of Turin, which was ardently opposed by Garibaldi. Garibaldi's family's involvement in coastal trade drew him to a life at sea. He participated actively in the Nizzardo Italians community and was certified in 1832 as a merchant navy captain.

He lived in Pera Pera may refer to:

Places

* Pera (Beyoğlu), a district in Istanbul formerly called Pera, now called Beyoğlu

** Galata, a neighbourhood of Beyoğlu, often referred to as Pera in the past

* Pêra (Caparica), a Portuguese locality in the district ...

district of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

from 1828 to 1832. He became an instructor and taught Italian, French and mathematics.

In April 1833, he travelled to Taganrog, in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, aboard the schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

''Clorinda'' with a shipment of oranges. During ten days in port, he met Giovanni Battista Cuneo from Oneglia

Oneglia ( lij, Inêia or ) is a former town in northern Italy on the Ligurian coast, in 1923 joined to Porto Maurizio to form the Comune of Imperia. The name is still used for the suburb.Roy Palmer Domenico, ''The regions of Italy: a referenc ...

, a politically active immigrant and member of the secret Young Italy movement of Giuseppe Mazzini. Mazzini was a passionate proponent of Italian unification as a liberal republic via political and social reform. Garibaldi joined the society and took an oath dedicating himself to the struggle to liberate and unify his homeland from Austrian dominance.

In November 1833, Garibaldi met Mazzini in Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, starting a long relationship that later became troubled. He joined the Carbonari revolutionary association, and in February 1834 participated in a failed Mazzinian insurrection in Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. A Genoese court sentenced Garibaldi to death ''in absentia'', and he fled across the border to Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

.

South America

Garibaldi first sailed to the

Garibaldi first sailed to the Beylik of Tunis

The Beylik of Tunis (), also known as Kingdom of Tunis ( ar, المملكة التونسية) was a largely autonomous beylik of the Ottoman Empire located in present-day Tunisia. It was ruled by the Husainid dynasty from 1705 until the aboli ...

before eventually finding his way to the Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and (until 1828) Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Dom ...

. Once there, he took up the cause of the Riograndense Republic

The Riograndense Republic, often called the Piratini Republic ( pt, República Rio-Grandense or ), was a ''de facto'' state that seceded from the Empire of Brazil and roughly coincided with the present state of Rio Grande do Sul. It was proc ...

in its attempt to separate from Brazil, joining the rebels known as the Ragamuffins in the Ragamuffin War of 1835.

During this war, he met Ana Maria de Jesus Ribeiro da Silva, commonly known as Anita. When the rebels proclaimed the Catarinense Republic in the Brazilian province of Santa Catarina in 1839, she joined him aboard his ship, ''Rio Pardo'', and fought alongside him at the battles of Imbituba and Laguna.

In 1841, Garibaldi and Anita moved to Montevideo

Montevideo () is the capital and largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . Montevideo is situated on the southern co ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, where Garibaldi worked as a trader and schoolmaster. The couple married in Montevideo the following year. They had four children; Domenico Menotti (1840–1903), Rosa (1843–1845), Teresa Teresita (1845–1903), and Ricciotti (1847–1924). A skilled horsewoman, Anita is said to have taught Giuseppe about the gaucho culture of Argentina, southern Brazil and Uruguay. Around this time he adopted his trademark clothing—the red shirt, poncho

A poncho (; qu, punchu; arn, pontro; "blanket", "woolen fabric") is an outer garment designed to keep the body warm. A rain poncho is made from a watertight material designed to keep the body dry from the rain. Ponchos have been used by the ...

, and sombrero commonly worn by gauchos.

In 1842, Garibaldi took command of the Uruguayan fleet and raised an Italian Legion of soldiers—known as Redshirts—for the Uruguayan Civil War. This recruitment was possible as Montevideo had a large Italian population at the time: 4,205 out of a total population of 30,000 according to an 1843 census.

Garibaldi aligned his forces with the Uruguayan Colorados led by Fructuoso Rivera and Joaquín Suárez, who were aligned with the Argentine Unitarian Party. This faction received some support from the French and British in their struggle against the forces of former Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe's Blancos, which was also aligned with Argentine Federales under the rule of

Garibaldi aligned his forces with the Uruguayan Colorados led by Fructuoso Rivera and Joaquín Suárez, who were aligned with the Argentine Unitarian Party. This faction received some support from the French and British in their struggle against the forces of former Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe's Blancos, which was also aligned with Argentine Federales under the rule of Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas.

The Italian Legion adopted a black flag that represented Italy in mourning, with a volcano at the center that symbolized the dormant power in their homeland. Though contemporary sources do not mention the Redshirts, popular history asserts that the legion first wore them in Uruguay, getting them from a factory in Montevideo that had intended to export them to the slaughterhouses of Argentina. These shirts became the symbol of Garibaldi and his followers.

Between 1842 and 1848, Garibaldi defended Montevideo against forces led by Oribe. In 1845, he managed to occupy Colonia del Sacramento and Martín García Island, and led the infamous sacks of Martín García island and Gualeguaychú during the Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata. Garibaldi saved his life after being defeated in the Costa Brava combat, delivered on 15 and 16 August 1842, thanks to the greatness of Admiral William Brown. The Argentines, wanting to pursue him to finish him off, were stopped by Brown who exclaimed "let him escape, that gringo is a brave man." Years later, a grandson of Garibaldi would be named William, in honor of Admiral Brown. Adopting amphibious guerrilla tactics, Garibaldi later achieved two victories during 1846, in the Battle of Cerro and the Battle of San Antonio del Santo.

Induction to Freemasonry

Garibaldi joined Freemasonry during his exile, taking advantage of the asylum the lodges offered to political refugees from European countries governed by despotic regimes. At the age of 37, during 1844, Garibaldi was initiated in the L' Asil de la Vertud Lodge of Montevideo. This was an irregular lodge under a Brazilian Freemasonry not recognized by the main international masonic obediences, such as the United Grand Lodge of England or theGrand Orient de France

The Grand Orient de France (GODF) is the oldest and largest of several Freemasonic organizations based in France and is the oldest in Continental Europe (as it was formed out of an older Grand Lodge of France in 1773, and briefly absorbed the ...

.

While Garibaldi had little use for Masonic rituals, he was an active Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and regarded Freemasonry as a network that united progressive men as brothers both within nations and as a global community. Garibaldi was eventually elected as the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy

The Grand Orient of Italy (GOI) ( it, Grande Oriente d'Italia) is an Italian masonic grand lodge founded in 1805; the viceroy Eugene of Beauharnais was instrumental in its establishment. It was based at the Palazzo Giustiniani, Rome, Italy from ...

.Garibaldi – the masonTranslated from Giuseppe Garibaldi Massone by the Grand Orient of Italy

/ref> Garibaldi regularized his position later in 1844, joining the lodge Les Amis de la Patrie of

Montevideo

Montevideo () is the capital and largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . Montevideo is situated on the southern co ...

under the Grand Orient of France.

Election of Pope Pius IX, 1846

The fate of his homeland continued to concern Garibaldi. The election ofPope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

in 1846 caused a sensation among Italian patriots, both at home and in exile. Pius's initial reforms seemed to identify him as the liberal pope called for by Vincenzo Gioberti, who went on to lead the unification of Italy. When news of these reforms reached Montevideo, Garibaldi wrote to the Pope:

Mazzini, from exile, also applauded the early reforms of Pius IX. In 1847, Garibaldi offered the apostolic nuncio at Rio de Janeiro, Bedini, the service of his Italian Legion for the liberation of the peninsula. Then news of an outbreak of revolution in Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

in January 1848 and revolutionary agitation elsewhere in Italy, encouraged Garibaldi to lead approximately 60 members of his legion home.

Return to Italy

First Italian War of Independence

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states and was one of the founders and leaders of the Action Party. Garibaldi offered his services to

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states and was one of the founders and leaders of the Action Party. Garibaldi offered his services to Charles Albert of Sardinia

Charles Albert (; 2 October 1798 – 28 July 1849) was the King of Sardinia from 27 April 1831 until 23 March 1849. His name is bound up with the first Italian constitution, the Statuto Albertino, Albertine Statute, and with the First Italian ...

, who displayed some liberal inclinations, but he treated Garibaldi with coolness and distrust. Rebuffed by the Piedmontese, he and his followers crossed into Lombardy where they offered assistance to the provisional government of Milan, which had rebelled against the Austrian occupation. In the course of the following unsuccessful First Italian War of Independence

The First Italian War of Independence ( it, Prima guerra d'indipendenza italiana), part of the Italian Unification (''Risorgimento''), was fought by the Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) and Italian volunteers against the Austrian Empire and other ...

, Garibaldi led his legion to two minor victories at Luino and Morazzone.

After the crushing Piedmontese defeat at the Battle of Novara on 23 March 1849, Garibaldi moved to Rome to support the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

recently proclaimed in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

. However, a French force sent by Louis Napoleon threatened to topple it. At Mazzini's urging, Garibaldi took command of the defence of Rome. In fighting near Velletri, Achille Cantoni saved his life. After Cantoni's death, during the battle of Mentana

The Battle of Mentana was fought on November 3, 1867, near the village of Mentana, located north-east of Rome (then in the Papal States, now modern Lazio), between French-papal troops and the Italian volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, who wer ...

, Garibaldi wrote the novel ''Cantoni the Volunteer''.

On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the Apennine mountains. Garibaldi, having entered the chamber covered in blood, made a speech favouring the third option, ending with: ''Ovunque noi saremo, sarà Roma.'' (Wherever we will go, that will be Rome).

The sides negotiated a truce on 1–2 July, Garibaldi withdrew from Rome with 4,000 troops, and an ambition to rouse popular rebellion against the Austrians in central Italy. The French Army entered Rome on 3 July and reestablished the

On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the Apennine mountains. Garibaldi, having entered the chamber covered in blood, made a speech favouring the third option, ending with: ''Ovunque noi saremo, sarà Roma.'' (Wherever we will go, that will be Rome).

The sides negotiated a truce on 1–2 July, Garibaldi withdrew from Rome with 4,000 troops, and an ambition to rouse popular rebellion against the Austrians in central Italy. The French Army entered Rome on 3 July and reestablished the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

's temporal power. Garibaldi and his forces, hunted by Austrian, French, Spanish, and Neapolitan troops, fled to the north, intending to reach Venice, where the Venetians were still resisting the Austrian siege. After an epic march, Garibaldi took temporary refuge in San Marino

San Marino (, ), officially the Republic of San Marino ( it, Repubblica di San Marino; ), also known as the Most Serene Republic of San Marino ( it, Serenissima Repubblica di San Marino, links=no), is the fifth-smallest country in the world an ...

, with only 250 men having not abandoned him. Anita, who was carrying their fifth child, died near Comacchio Comacchio (; egl, label= Comacchiese, Cmâc' ) is a town and '' comune'' of Emilia Romagna, Italy, in the province of Ferrara, from the provincial capital Ferrara. It was founded about two thousand years ago; across its history it was first g ...

during the retreat.

North America and the Pacific

Garibaldi eventually managed to reachPorto Venere

Porto Venere (; until 1991 ''Portovenere''; lij, Pòrtivene) is a town and ''comune'' (municipality) located on the Ligurian coast of Italy in the province of La Spezia. It comprises the three villages of Fezzano, Le Grazie and Porto Venere, an ...

, near La Spezia

La Spezia (, or , ; in the local Spezzino dialect) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second largest cit ...

, but the Piedmontese government forced him to emigrate again. He went to Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

, where he stayed with Francesco Carpanetto, a wealthy Italian merchant. Carpanetto suggested that he and some of his associates finance the purchase of a merchant ship, which Garibaldi would command. Garibaldi agreed, feeling that his political goals were, for the moment, unreachable, and he could at least earn a living.

Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey b ...

. (The cottage where he stayed is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

and is preserved as the Garibaldi Memorial.) Garibaldi was not satisfied with this, and in April 1851 he left New York with his friend Carpanetto for Central America, where Carpanetto was establishing business operations. They first went to Nicaragua, and then to other parts of the region. Garibaldi accompanied Carpanetto as a companion, not a business partner, and used the name ''Giuseppe Pane''.

Carpanetto went on to Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

, Peru, where a shipload of his goods was due, arriving late in 1851 with Garibaldi. En route, Garibaldi called on revolutionary heroine Manuela Sáenz. At Lima, Garibaldi was generally welcomed. A local Italian merchant, Pietro Denegri, gave him command of his ship ''Carmen'' for a trading voyage across the Pacific. Garibaldi took the ''Carmen'' to the Chincha Islands for a load of guano. Then on 10 January 1852, he sailed from Peru for Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ente ...

, China, arriving in April.

After side trips to Xiamen

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong' ...

and Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populated ...

, Garibaldi brought the ''Carmen'' back to Peru via the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific, passing clear around the south coast of Australia. He visited Three Hummock Island in the Bass Strait

Bass Strait () is a strait separating the island states and territories of Australia, state of Tasmania from the Australian mainland (more specifically the coast of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, with the exception of the land border across Bo ...

. Garibaldi then took the ''Carmen'' on a second voyage: to the United States via Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

with copper from Chile, and also wool. Garibaldi arrived in Boston and went on to New York. There he received a hostile letter from Denegri and resigned his command. Another Italian, Captain Figari, had just come to the U.S. to buy a ship and hired Garibaldi to take the ship to Europe. Figari and Garibaldi bought the ''Commonwealth'' in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, and Garibaldi left New York for the last time in November 1853. He sailed the ''Commonwealth'' to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, and then to Newcastle on the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wat ...

for coal.

Tyneside

The ''Commonwealth'' arrived on 21 March 1854. Garibaldi, already a popular figure onTyneside

Tyneside is a built-up area across the banks of the River Tyne in northern England. Residents of the area are commonly referred to as Geordies. The whole area is surrounded by the North East Green Belt.

The population of Tyneside as publishe ...

, was welcomed enthusiastically by local working men-although the ''Newcastle Courant'' reported that he refused an invitation to dine with dignitaries in the city. He stayed in Huntingdon Place Tynemouth for a few days, and in South Shields

South Shields () is a coastal town in South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England. It is on the south bank of the mouth of the River Tyne. Historically, it was known in Roman times as Arbeia, and as Caer Urfa by Early Middle Ages. According to the 20 ...

on Tyneside for over a month, departing at the end of April 1854. During his stay, he was presented with an inscribed sword, which his grandson Giuseppe Garibaldi II later carried as a volunteer in British service in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

. He then sailed to Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, where his five years of exile ended on 10 May 1854.

Second Italian War of Independence

Garibaldi returned to Italy in 1854. Using an inheritance from the death of his brother, he bought half of the Italian island ofCaprera

Caprera is an island in the Maddalena archipelago off the coast of Sardinia, Italy. In the area of La Maddalena island in the Strait of Bonifacio, it is a tourist destination and the place to which Giuseppe Garibaldi retired from 1854 until ...

(north of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

), devoting himself to agriculture. In 1859, the Second Italian War of Independence (also known as the Austro-Sardinian War) broke out in the midst of internal plots at the Sardinian government. Garibaldi was appointed major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

and formed a volunteer unit named the Hunters of the Alps

The Hunters of the Alps ( it, Cacciatori delle Alpi) were a military corps created by Giuseppe Garibaldi in Cuneo on 20 February 1859 to help the regular Sardinian army to free the northern part of Italy in the Second Italian War of Independe ...

(''Cacciatori delle Alpi''). Thenceforth, Garibaldi abandoned Mazzini's republican ideal of the liberation of Italy, assuming that only the Sardinian monarchy could effectively achieve it. He and his volunteers won victories over the Austrians at Varese

Varese ( , , or ; lmo, label=Varesino, Varés ; la, Baretium; archaic german: Väris) is a city and ''comune'' in north-western Lombardy, northern Italy, north-west of Milan. The population of Varese in 2018 has reached 80,559.

It is the ca ...

, Como

Como (, ; lmo, Còmm, label= Comasco , or ; lat, Novum Comum; rm, Com; french: Côme) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy. It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como.

Its proximity to Lake Como and to the Alps ...

, and other places.

Garibaldi was very displeased as his home city of Nice (''Nizza'' in Italian) had surrendered to the French in return for crucial military assistance. In April 1860, as deputy for Nice in the Piedmontese parliament at Turin, he vehemently attacked Cavour for ceding Nice and the County of Nice (''Nizzardo'') to Louis Napoleon, Emperor of France. In the following years, Garibaldi (with other passionate '' Nizzardo Italians'') promoted the '' Italian irredentism'' of his ''Nizza'', even with riots (in 1872).

Campaign of 1860

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

and Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and al ...

provided Garibaldi with an opportunity. He gathered about a thousand volunteers called ''i Mille'' (the Thousand), or the Redshirts as popularly known, in two ships named ''Il Piemonte'' and ''Il Lombardo'', and left from Quarto, in Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, on 5 May in the evening and landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily, on 11 May.

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 on the hill of

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 on the hill of Calatafimi

Calatafimi-Segesta, commonly known as simply Calatafimi, is a small town in the province of Trapani, in Sicily, southern Italy.

The full name of the municipality was created in 1997 and is meant to highlight the presence within its territory of t ...

on 15 May. He used the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge. He saw that the hill was terraced, and the terraces would shelter his advancing men. Though small by comparison with the coming clashes at Palermo, Milazzo, and Volturno, this battle was decisive in establishing Garibaldi's power in the island. An apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant Nino Bixio, "Here we either make Italy, or we die." In reality, the Neapolitan forces were ill-guided, and most of its higher officers had been bought out.

The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. He advanced to the outskirts of Palermo, the capital of the island, and launched a siege on 27 May. He had the support of many inhabitants, who rose up against the garrison—but before they could take the city, reinforcements arrived and bombarded the city nearly to ruins. At this time, a British admiral intervened and facilitated a truce, by which the Neapolitan

Neapolitan means of or pertaining to Naples, a city in Italy; or to:

Geography and history

* Province of Naples, a province in the Campania region of southern Italy that includes the city

* Duchy of Naples, in existence during the Early and Hig ...

royal troops and warships surrendered the city and departed. The young Henry Adams—later to become a distinguished American writer—visited the city in June and described the situation, along with his meeting with Garibaldi, in a long and vivid letter to his older brother Charles. Historians Clough et al. argue that Garibaldi's Thousand were students, independent artisans, and professionals, not peasants. The support given by Sicilian peasants was not out of a sense of patriotism but from their hatred of exploitative landlords and oppressive Neapolitan officials. Garibaldi himself had no interest in social revolution and instead sided with the Sicilian landlords against the rioting peasants.

By conquering Palermo, Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island, winning a ferocious and difficult battle at Milazzo. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted.

By conquering Palermo, Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island, winning a ferocious and difficult battle at Milazzo. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted.

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina and marched north. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on 7 September he entered the capital city of

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina and marched north. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on 7 September he entered the capital city of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, by train. Despite taking Naples, however, he had not to this point defeated the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi's volunteer army of 24,000 was not able to defeat conclusively the reorganized Neapolitan army—about 25,000 men—on 30 September at the battle of Volturno. This was the largest battle he ever fought, but its outcome was effectively decided by the arrival of the Piedmontese Army.

Following this, Garibaldi's plans to march on to Rome were jeopardized by the Piedmontese, technically his ally but unwilling to risk war with France, whose army protected the Pope. The Piedmontese themselves had conquered most of the Pope's territories in their march south to meet Garibaldi, but they had deliberately avoided Rome, capital of the Papal state. Garibaldi chose to hand over all his territorial gains in the south to the Piedmontese and withdrew to Caprera and temporary retirement. Some modern historians consider the handover of his gains to the Piedmontese as a political defeat, but he seemed willing to see Italian unity brought about under the Piedmontese Crown. The meeting at Teano between Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II is the most important event in modern Italian history but is so shrouded in controversy that even the exact site where it took place is in doubt.

Aftermath

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and '' realpolitik'', but he also bore a personal grudge for Cavour's trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he supported the Sardinian monarch,

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and '' realpolitik'', but he also bore a personal grudge for Cavour's trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he supported the Sardinian monarch, Victor Emmanuel II

en, Victor Emmanuel Maria Albert Eugene Ferdinand Thomas

, house = Savoy

, father = Charles Albert of Sardinia

, mother = Maria Theresa of Austria

, religion = Roman Catholicism

, image_size = 252px

, succession ...

, who in his opinion had been chosen by Providence for the liberation of Italy. In his famous meeting with Victor Emmanuel at Teano on 26 October 1860, Garibaldi greeted him as King of Italy

King of Italy ( it, links=no, Re d'Italia; la, links=no, Rex Italiae) was the title given to the ruler of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The first to take the title was Odoacer, a barbarian military leader ...

and shook his hand. Garibaldi rode into Naples at the king's side on 7 November, then retired to the rocky island of Caprera

Caprera is an island in the Maddalena archipelago off the coast of Sardinia, Italy. In the area of La Maddalena island in the Strait of Bonifacio, it is a tourist destination and the place to which Giuseppe Garibaldi retired from 1854 until ...

, refusing to accept any reward for his services.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

(in 1861), he was a very popular figure. The 39th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment was named ''Garibaldi Guard'' after him.Civil War Home– The Civil War Society's "Encyclopedia of the Civil War" – Italian-Americans in the Civil War. Garibaldi expressed interest in aiding the Union, and he was offered a major general's commission in the U.S. Army through a letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to Henry S. Sanford, the U.S. Minister at Brussels, 27 July 1861. On 9 September 1861, Sanford met with Garibaldi and reported the result of the meeting to Seward: This meeting occurred a year before Lincoln was ready to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Sanford's mission was hopeless, and Garibaldi did not join the Union army. A historian of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Don H. Doyle, however, wrote, "Garibaldi's full-throated endorsement of the Union cause roused popular support just as news of the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

broke in Europe." On 6 August 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

had been issued, Garibaldi wrote to Lincoln, "Posterity will call you the great emancipator, a more enviable title than any crown could be, and greater than any merely mundane treasure."

On 5 October 1861, Garibaldi set up the International Legion

The International Legion was created in Italy by Giuseppe Garibaldi, on October 5, 1860 – in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Volturnus, where the forces of the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies were decisively broken.

It had been t ...

bringing together different national divisions of French, Poles, Swiss, Germans and other nationalities, with a view not just of finishing the liberation of Italy, but also of their homelands. With the motto "Free from the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

to the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

," the unification movement set its gaze on Rome and Venice. Mazzini was discontented with the perpetuation of monarchial government, and continued to agitate for a republic. Garibaldi, frustrated at inaction by the king, and bristling over perceived snubs, organized a new venture. This time, he intended to take on the Papal States.

Expedition against Rome

Garibaldi himself was intensely anti-Catholic and anti-papal. His efforts to overthrow the Pope by military action mobilized anti-Catholic support. There were major anti-Catholic riots in his name across Britain in 1862, with the Irish Catholics fighting in defense of their Church. Garibaldi's hostility to the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French Emperor

Garibaldi himself was intensely anti-Catholic and anti-papal. His efforts to overthrow the Pope by military action mobilized anti-Catholic support. There were major anti-Catholic riots in his name across Britain in 1862, with the Irish Catholics fighting in defense of their Church. Garibaldi's hostility to the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

had guaranteed the independence of Rome from Italy by stationing a French garrison in Rome. Victor Emmanuel was wary of the international repercussions of attacking Rome and the Pope's seat there, and discouraged his subjects from participating in revolutionary ventures with such intentions. Nonetheless, Garibaldi believed he had the secret support of his government.

In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa to Palermo to gather volunteers for the impending campaign, under the slogan ''Roma o Morte'' (Rome or Death). An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. He arrived with a force of around two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from

In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa to Palermo to gather volunteers for the impending campaign, under the slogan ''Roma o Morte'' (Rome or Death). An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. He arrived with a force of around two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also b ...

, where Garibaldi declared that he would enter Rome as a victor or perish beneath its walls. He landed at Melito on 14 August, and marched at once into the Calabrian mountains.

Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged

Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged Aspromonte

The Aspromonte is a mountain massif in the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria ( Calabria, southern Italy). The literal translation of the name means "rough mountain". But for others the name more likely is related to the Greek word Aspros ( � ...

. One of the regulars fired a chance shot, and several volleys followed, killing a few of the volunteers. The fighting ended quickly, as Garibaldi forbade his men to return fire on fellow subjects of the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

. Many of the volunteers were taken prisoner, including Garibaldi, who had been wounded by a shot in the foot. The episode was the origin of a famous Italian nursery rhyme: ''Garibaldi fu ferito'' ("Garibaldi was wounded").

A government steamer took him to a prison at Varignano near La Spezia

La Spezia (, or , ; in the local Spezzino dialect) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second largest cit ...

, where he was held in a sort of honorable imprisonment and underwent a tedious and painful operation to heal his wound. His venture had failed, but he was consoled by Europe's sympathy and continued interest. After he regained his health, the government released Garibaldi and let him return to Caprera.

En route to London in 1864 he stopped briefly in Malta, where many admirers visited him in his hotel. Protests by opponents of his anticlericalism were suppressed by the authorities. In London his presence was received with enthusiasm by the population. He met the British Prime Minister Viscount Palmerston, as well as revolutionaries then living in exile in the city. At that time, his ambitious international project included the liberation of a range of occupied nations, such as Croatia, Greece, and Hungary. He also visited Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst t ...

and was given a tour of the Britannia Iron Works, where he planted a tree (which was cut down in 1944 due to decay).

Final struggle with Austria

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

had broken out, and Italy had allied with Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

against the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

in the hope of taking Venetia from Austrian rule ( Third Italian War of Independence). Garibaldi gathered again his Hunters of the Alps, now some 40,000 strong, and led them into the Trentino

Trentino ( lld, Trentin), officially the Autonomous Province of Trento, is an autonomous province of Italy, in the country's far north. The Trentino and South Tyrol constitute the region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, an autonomous region ...

. He defeated the Austrians at Bezzecca, and made for Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin and lmo, Trent; german: Trient ; cim, Tria; , ), also anglicized as Trent, is a city on the Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th centu ...

.

The Italian regular forces were defeated at Lissa on the sea, and made little progress on land after the disaster of Custoza. The sides signed an armistice by which Austria ceded Venetia to Italy, but this result was largely due to Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought, and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. Garibaldi answered with a short telegram from the main square of Bezzecca with the famous motto: ''Obbedisco!'' ("I obey!").

After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly armed volunteers. He was shot in the leg in the

The Italian regular forces were defeated at Lissa on the sea, and made little progress on land after the disaster of Custoza. The sides signed an armistice by which Austria ceded Venetia to Italy, but this result was largely due to Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought, and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. Garibaldi answered with a short telegram from the main square of Bezzecca with the famous motto: ''Obbedisco!'' ("I obey!").

After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly armed volunteers. He was shot in the leg in the Battle of Mentana

The Battle of Mentana was fought on November 3, 1867, near the village of Mentana, located north-east of Rome (then in the Papal States, now modern Lazio), between French-papal troops and the Italian volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, who wer ...

, and had to withdraw from the Papal territory. The Italian government again imprisoned him for some time, after which he returned to Caprera.

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the League of Peace and Freedom

The Ligue internationale de la paix (League of Peace and Freedom) was created after a public opinion campaign against a war between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia over Luxembourg. The Luxembourg crisis was peacefully resolved ...

in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

he proposed: "The papacy, being the most harmful of all secret societies, ought to be abolished."

Franco-Prussian War

When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in July 1870, Italian public opinion heavily favored the Prussians, and many Italians attempted to sign up as volunteers at the Prussian embassy in Florence. After the French garrison was recalled from Rome, the Italian Army captured the Papal States without Garibaldi's assistance. Following the wartime collapse of theSecond French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930s ...

after the Battle of Sedan