German–Soviet Union relations date to the

aftermath of the First World War

The aftermath of World War I saw drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, ne ...

. The

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

, dictated by Germany ended hostilities between Russia and Germany; it was signed on March 3, 1918. A few months later, the German ambassador to Moscow,

Wilhelm von Mirbach

Wilhelm Maria Theodor Ernst Richard Graf von Mirbach-Harff (2 July 1871 – 6 July 1918) was a German diplomat, and was assassinated while ambassador to Moscow.

Biography

Born in Bad Ischl in Upper Austria into a Catholic Rhenan aristocratic ...

, was shot dead by Russian

Left Socialist-Revolutionaries

The Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (russian: Партия левых социалистов-революционеров-интернационалистов) was a revolutionary socialist political party formed during the Russian Rev ...

in an attempt to incite a new war between Russia and Germany. The entire Soviet embassy under

Adolph Joffe

Adolph Abramovich Joffe (russian: Адо́льф Абра́мович Ио́ффе, alternative transliterations Adol'f Ioffe or, rarely, Yoffe) (10 October 1883 in Simferopol – 16 November 1927 in Moscow) was a Russian revolutionary, a Bo ...

was deported from Germany on November 6, 1918, for their active support of the

German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

.

Karl Radek

Karl Berngardovich Radek (russian: Карл Бернгардович Радек; 31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a Russian revolutionary and a Marxist active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and a ...

also illegally supported communist subversive activities in

Weimar Germany

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

in 1919.

From the outset, both states sought to overthrow the system that was established by the victors of World War I. Germany, laboring under onerous reparations and stung by the collective responsibility provisions of the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, was a defeated nation in turmoil. This and the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

made both Germany and the Soviets into international outcasts, and their resulting

rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual enemy, as was the case with Germ ...

during the

interbellum

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relative ...

was a natural convergence.

[Gasiorowski, Zygmunt J. (1958)]

The Russian Overture to Germany of December 1924

''The Journal of Modern History

''The Journal of Modern History'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering European intellectual, political, and cultural history, published by the University of Chicago Press. Established in 1929, the journal covers events from app ...

'' 30 (2), 99–117.[Large, J. A. (1978)]

The Origins of Soviet Collective Security Policy, 1930–32

''Soviet Studies

''Europe-Asia Studies'' is an academic peer-reviewed journal published 10 times a year by Routledge on behalf of the Institute of Central and East European Studies, University of Glasgow, and continuing (since vol. 45, 1993) the journal ''Soviet St ...

'' 30 (2), 212–236. At the same time, the dynamics of their relationship was shaped by both a lack of trust and the respective governments' fears of its partner's breaking out of diplomatic isolation and turning towards the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

(which at the time was thought to possess the greatest military strength in Europe) and the

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

,

its ally. The countries'

economic relationship dwindled in 1933, when

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

came to power and created

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

; however, the relationships restarted in the end of 1930s, culminating with the

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

of 1939 and several trade agreements.

Few questions concerning the

causes of World War II

The causes of World War II, a global war from 1939 to 1945 that was the deadliest conflict in human history, have been given considerable attention by historians from many countries who studied and understood them. The immediate precipitating ...

are more controversial and ideologically loaded than the issue of the policies of the Soviet Union under

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

towards Nazi Germany between the

Nazi seizure of power

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

and the

German invasion of the USSR

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

on June 22, 1941.

[Haslam, Jonathan (1997). "Soviet-German Relations and the Origins of the Second World War: The Jury Is Still Out". '']The Journal of Modern History

''The Journal of Modern History'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering European intellectual, political, and cultural history, published by the University of Chicago Press. Established in 1929, the journal covers events from app ...

'' 69: 785–797. A variety of competing and contradictory theses exist, including: that the Soviet leadership actively sought another great war in Europe to further weaken the capitalist nations; that the USSR pursued a purely defensive policy; or that the USSR tried to avoid becoming entangled in a war, both because Soviet leaders did not feel that they had the military capabilities to conduct strategic operations at that time, and to avoid, in paraphrasing Stalin's words to the 18th Party Congress on March 10, 1939, "pulling other nations' (the UK and France's) chestnuts out of the fire."

Soviet Russia and Weimar Germany

Revolution and end of World War I

The outcome of the First World War was disastrous for both the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

and the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. During the war, the

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

struggled for survival, and

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

had no option except to recognize the independence of

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

,

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

,

Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

,

Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

and

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. Moreover, facing a German military advance, Lenin and

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

were forced to enter into the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

, which ceded large swathes of western Russian territory to the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

. On 11 November 1918, the Germans signed an

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

with the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, ending the First World War on the

Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

. After Germany's collapse,

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

,

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

troops intervened in the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

.

[ Montefiore 2005, p. 32]

Initially, the Soviet leadership hoped for a successful socialist revolution in Germany as part of the "

world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

". However,

the revolution was put down by the right-wing

freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

. Subsequently, the Bolsheviks became embroiled in the

Soviet war with Poland of 1919–20. Because Poland was a traditional enemy of Germany (see e.g.

Silesian Uprisings), and because the Soviet state was also isolated internationally, the Soviet government began to seek a closer relationship with Germany and therefore adopted a much less hostile attitude towards Germany. This line was consistently pursued under

People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin

Georgy Vasilyevich Chicherin (24 November 1872 – 7 July 1936), also spelled Tchitcherin, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and a Soviet politician who served as the first People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the Soviet government from ...

and Soviet Ambassador

Nikolay Krestinsky

Nikolay Nikolayevich Krestinsky (russian: Никола́й Никола́евич Крести́нский; 13 October 1883 – 15 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet politician who served as the Responsible Sec ...

. Other Soviet representatives instrumental in the negotiations were

Karl Radek

Karl Berngardovich Radek (russian: Карл Бернгардович Радек; 31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a Russian revolutionary and a Marxist active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and a ...

,

Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (russian: Леони́д Бори́сович Кра́син; 15 July 1870 – 24 November 1926) was a Russian Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary politician and a Soviet diplomat. In ...

,

Christian Rakovsky

Christian Georgievich Rakovsky (russian: Христиа́н Гео́ргиевич Рако́вский; bg, Кръстьо Георги́ев Рако́вски; – September 11, 1941) was a Bulgarian-born socialist revolutionary, a Bolshevi ...

,

Victor Kopp and

Adolph Joffe

Adolph Abramovich Joffe (russian: Адо́льф Абра́мович Ио́ффе, alternative transliterations Adol'f Ioffe or, rarely, Yoffe) (10 October 1883 in Simferopol – 16 November 1927 in Moscow) was a Russian revolutionary, a Bo ...

.

In the 1920s, many in the leadership of

Weimar Germany

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

, who felt humiliated by the conditions that the Treaty of Versailles had imposed after their defeat in the First World War (especially General

Hans von Seeckt

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (22 April 1866 – 27 December 1936) was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for Germany ...

, chief of the

Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

), were interested in cooperation with the Soviet Union, both in order to avert any threat from the

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

,

backed by the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

, and to prevent any possible Soviet-British alliance. The specific German aims were the full rearmament of the Reichswehr, which was explicitly prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles, and an alliance against Poland. It is unknown exactly when the first contacts between von Seeckt and the Soviets took place, but it could have been as early as 1919–1921, or possibly even before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

On April 16, 1920, Victor Kopp, the

RSFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

's special representative to Berlin, asked at the German Foreign Office whether "there was any possibility of combining the German and the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

for a joint war on

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

". This was yet another event at the start of military cooperation between the two countries, which ended before the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

By early 1921, a special group in the Reichswehr Ministry devoted to Soviet affairs, ''Sondergruppe R'', had been created.

[ Gatzke, Hans W. (1958)]

Russo-German Military Collaboration during the Weimar Republic

''The American Historical Review'' 63 (3), 565–597

online

/ref>

Weimar Germany's army had been limited to 100,000 men by the Treaty of Versailles, which also forbade the Germans to have aircraft, tanks, submarines, heavy artillery, poison gas, anti-tank weapons or many anti-aircraft guns. A team of inspectors from the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

patrolled many German factories and workshops to ensure that these weapons were not being manufactured.

Treaty of Rapallo 1922 and secret military cooperation

The Treaty of Rapallo between Weimar Germany and Soviet Russia was signed by German Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau (29 September 1867 – 24 June 1922) was a German industrialist, writer and liberal politician.

During the First World War of 1914–1918 he was involved in the organization of the German war economy. After the war, Rathenau s ...

and his Soviet colleague Georgy Chicherin

Georgy Vasilyevich Chicherin (24 November 1872 – 7 July 1936), also spelled Tchitcherin, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and a Soviet politician who served as the first People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the Soviet government from ...

on April 16, 1922, during the Genoa Economic Conference, annulling all mutual claims, restoring full diplomatic relations, and establishing the beginnings of close trade relationships, which made Weimar Germany the main trading and diplomatic partner of Soviet Russia.

Rumors of a secret military supplement to the treaty soon spread. However, for a long time the consensus was that those rumors were wrong, and that Soviet-German military negotiations were independent of Rapallo and kept secret from the German Foreign Ministry

The Federal Foreign Office (german: Auswärtiges Amt, ), abbreviated AA, is the foreign ministry of the Federal Republic of Germany, a federal agency responsible for both the country's foreign policy and its relationship with the European Union. ...

for some time.Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

General Staff.

The first German officers went to Soviet Russia for these purposes in March 1922. One month later, Junkers

Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (JFM, earlier JCO or JKO in World War I, English: Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works) more commonly Junkers , was a major German aircraft and aircraft engine manufacturer. It was founded there in Dessau, Ge ...

began building aircraft at Fili, outside Moscow, in violation of Versailles.Andrei Tupolev

Andrei Nikolayevich Tupolev (russian: Андрей Николаевич Туполев; – 23 December 1972) was a Russian and later Soviet aeronautical engineer known for his pioneering aircraft designs as Director of the Tupolev Design ...

or Pavel Sukhoi.Tupolev TB-1

The Tupolev TB-1 (development name ANT-4) was a Soviet bomber aircraft, an angular monoplane that served as the backbone of the Soviet bomber force for many years, and was the first large all-metal aircraft built in the Soviet Union.

Design and ...

and Tupolev TB-3

The Tupolev TB-3 (russian: Тяжёлый Бомбардировщик, Tyazhyolyy Bombardirovshchik, Heavy Bomber, civilian designation ANT-6) was a monoplane heavy bomber deployed by the Soviet Air Force in the 1930s and used during the early ...

.Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krupp ...

was soon active in the south of the USSR, near Rostov-on-Don

Rostov-on-Don ( rus, Ростов-на-Дону, r=Rostov-na-Donu, p=rɐˈstof nə dɐˈnu) is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the Eas ...

. In 1925, a flying school was established near Lipetsk

Lipetsk ( rus, links=no, Липецк, p=ˈlʲipʲɪtsk), also romanized as Lipeck, is a city and the administrative center of Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, located on the banks of the Voronezh River in the Don basin, southeast of Moscow. Popu ...

(Lipetsk fighter-pilot school

The Lipetsk fighter-pilot school (german: Kampffliegerschule Lipezk), also known as WIWUPAL from its German codename ''Wissenschaftliche Versuchs- und Personalausbildungsstation'' "Scientific Experimental and Personnel Training Station", was a secr ...

) to train the first pilots for the future Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

.Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzan is the capital city, capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and t ...

( Kama tank school) and a chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

facility in Saratov Oblast

Saratov Oblast (russian: Сара́товская о́бласть, ''Saratovskaya oblast'') is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast), located in the Volga Federal District. Its administrative center is the city of Saratov. As of the 2010 Cen ...

(Tomka gas test site

Tomka gas test site (german: Gas-Testgelände Tomka) was a secret chemical weapons testing facility near a place codenamed Volsk-18 (Wolsk, in German literature), 20 km off Volsk, now Shikhany, Saratov Oblast, Russia created within the frame ...

). In turn, the Red Army gained access to these training facilities, as well as military technology and theory from Weimar Germany.

The Soviets offered submarine-building facilities at a port on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, but this was not taken up. The ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

'' did take up a later offer of a base near Murmansk, where German vessels could hide from the British. During the Cold War, this base at Polyarnyy (which had been built especially for the Germans) became the largest weapons store in the world.

Documentation

Most of the documents pertaining to secret German-Soviet military cooperation were systematically destroyed in Germany. The Polish and French intelligence communities of the 1920s were remarkably well-informed regarding the cooperation. This did not, however, have any immediate effect upon German relations with other European powers. After World War II, the papers of General Hans von Seeckt and memoirs of other German officers became available,dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

, a handful of Soviet documents regarding this were published.

Relations in the 1920s

Trade

Since the late nineteenth century, Germany, which has few natural resources,

Since the late nineteenth century, Germany, which has few natural resources,raw materials

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feeds ...

.

Plans for Poland

Alongside the Soviet Union's military and economic assistance, there was also political backing for Germany's aspirations. On July 19, 1920, Victor Kopp told the German Foreign Office that Soviet Russia wanted "a common frontier with Germany, south of Lithuania, approximately on a line with Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok U ...

". In other words, Poland was to be partitioned once again. These promptings were repeated over the years, with the Soviets always anxious to stress that ideological differences between the two governments were of no account; all that mattered was that the two countries were pursuing the same foreign policy objectives.

On December 4, 1924, Victor Kopp, worried that the expected admission of Germany to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

(Germany was finally admitted to the League in 1926) was an anti-Soviet move, offered German Ambassador Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau

Ulrich Karl Christian Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau (29 May 1869 – 8 September 1928) was a German diplomat who became the first Foreign Minister of the Weimar Republic. In that capacity, he led the German delegation at the Paris Peace Conference ...

to cooperate against the Second Polish Republic, and secret negotiations were sanctioned.Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

rejected any venture into war.

Diplomatic relations

By 1919, both Germany and Russia were pariah nations in the eyes of democratic leaders. Both were excluded from major conferences and were deeply distrusted. The effect was to bring Moscow and Berlin closer together, most notably at Rapallo. German diplomats worried at the revolutionary nature of the Soviet Union, but were reassured by Lenin's New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

that seem to restore a semblance of capitalism. Berlin officials concluded that their policy of engagement was a success. However, 1927 Berlin realized that the Comintern, and Stalin, did not reflect a retreat from revolutionary Marxist–Leninism.

In 1925, Germany broke its diplomatic isolation and took part in the Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties were seven agreements negotiated at Locarno, Switzerland, during 5 to 16 October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central a ...

with France and Belgium, undertaking not to attack them. The Soviet Union saw western European ''détente'' as potentially deepening its own political isolation in Europe, in particular by diminishing Soviet-German relationships. As Germany became less dependent on the Soviet Union, it became more unwilling to tolerate subversive Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

interference:Rote Hilfe

The Rote Hilfe ("Red Aid") was the German affiliate of the International Red Aid. The Rote Hilfe was affiliated with the Communist Party of Germany and existed between 1924 and 1936. Its purpose was to provide help to those Communists who had be ...

, a Communist Party organization, were tried for treason in Leipzig in what was known as the Cheka Trial.

On April 24, 1926, Weimar Germany and the Soviet Union concluded another treaty (Treaty of Berlin (1926)

The Treaty of Berlin (German-Soviet Neutrality and Nonaggression Pact) was a treaty signed on 24 April 1926 under which Germany and the Soviet Union pledged neutrality in the event of an attack on the other by a third party for five years. The ...

), declaring the parties' adherence to the Treaty of Rapallo and neutrality for five years. The treaty was signed by German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman who served as chancellor in 1923 (for 102 days) and as foreign minister from 1923 to 1929, during the Weimar Republic.

His most notable achievement was the reconci ...

and Soviet ambassador Nikolay Krestinsky

Nikolay Nikolayevich Krestinsky (russian: Никола́й Никола́евич Крести́нский; 13 October 1883 – 15 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet politician who served as the Responsible Sec ...

. The treaty was perceived as an imminent threat by Poland (which contributed to the success of the May Coup in Warsaw), and with caution by other European states regarding its possible effect upon Germany's obligations as a party to the Locarno Agreements. France also voiced concerns in this regard in the context of Germany's expected membership in the League of Nations.

Third Period

In 1928, the 9th Plenum of the Executive Committee of the Communist International

The Executive Committee of the Communist International, commonly known by its acronym, ECCI (Russian acronym ИККИ), was the governing authority of the Comintern between the World Congresses of that body. The ECCI was established by the Founding ...

and its 6th Congress in Moscow favored Stalin's program over the line pursued by Comintern Secretary General Nikolay Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory.

...

. Unlike Bukharin, Stalin believed that a deep crisis in western capitalism was imminent, and he denounced the cooperation of international communist parties with social democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

movements, labelling them as social fascists, and insisted on a far stricter subordination of international communist parties to the Comintern, that is, to Soviet leadership. This was known as the Third Period

The Third Period is an ideological concept adopted by the Communist International (Comintern) at its Sixth World Congress, held in Moscow in the summer of 1928. It set policy until reversed when the Nazis took over Germany in 1933.

The Comint ...

. The policy of the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

(KPD) under Ernst Thälmann

Ernst Johannes Fritz Thälmann (; 16 April 1886 – 18 August 1944) was a German communist politician, and leader of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) from 1925 to 1933.

A committed Marxist-Leninist and Stalinist, Thälmann played a major r ...

was altered accordingly. The relatively independent KPD of the early 1920s almost completely subordinated itself to the Soviet Union.[Kevin McDermott, and J. Agnew, ''The Comintern: a History of International Communism from Lenin to Stalin'' (1996).]

Stalin's order that the German Communist party must never again vote with the Social Democrats coincided with his agreement, in December 1928, with what was termed the ' Union of Industrialists'. Under this agreement the Union of Industrialists agreed to provide the Soviet Union with an up-to-date armaments industry and the industrial base to support it, on two conditions:anti-aircraft guns

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

, howitzers

A howitzer () is a long-ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like oth ...

, anti-tank guns

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first dev ...

, machine guns

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) ...

etc., but he was critically short of money. As Russia had been a major wheat exporter before the First World War, he decided to expel his recalcitrant kulak peasant farmers to the wastes of Siberia and create huge collective farms on their land like the 50,000 hectare farm that Krupp had created in the North Caucasus. Thus, in 1930 and 1931, a huge deluge of Soviet wheat at slave labour prices flooded unsuspecting world markets, where surpluses already prevailed, thereby causing poverty and distress to North American farmers. However, Stalin secured the precious foreign currency to pay for German armaments.

Yet the Union of Industrialists were not only interested in cash for their weapons, they wanted a political concession. They feared the arrival of socialism in Germany and were irate at the KPD and Social Democrats objecting to providing funds for the development of new armored cruisers

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

. Stalin would have had no compunction about ordering the German Communists to change sides if it suited his purpose. He had negotiated with the German armaments makers throughout the summer of 1928 and was determined to modernize his armed forces. From 1929 onwards, therefore, the Communists voted faithfully with the far right DNVP

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...

and Hitler's NSDAP in the Reichstag despite fighting them in the streets.

Relying on the foreign affairs doctrine pursued by the Soviet leadership in the 1920s, in his report of the Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party organizations, the ...

to the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

of the All-Union Communist Party (b) on June 27, 1930, Joseph Stalin welcomed the international destabilization and rise of political extremism among the capitalist powers.

Early 1930s

The most intensive period of Soviet military collaboration with Weimar Germany was 1930–1932. On June 24, 1931, an extension of the 1926 Berlin Treaty was signed, though it was not until 1933 that it was ratified by the Reichstag due to internal political struggles. Some Soviet mistrust arose during the Lausanne Conference of 1932

The Lausanne Conference was a 1932 meeting of representatives from the United Kingdom, Germany, and France that resulted in an agreement to suspend World War I reparations payments imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. Held from June 16 ...

, when it was rumored that German Chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany ...

had offered French Prime Minister Édouard Herriot

Édouard Marie Herriot (; 5 July 1872 – 26 March 1957) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic who served three times as Prime Minister (1924–1925; 1926; 1932) and twice as President of the Chamber of Deputies. He led the f ...

a military alliance. The Soviets were also quick to develop their own relations with France and its main ally, Poland. This culminated in the conclusion of the Soviet-Polish Non-Aggression Pact on July 25, 1932, and the Soviet-French non-aggression pact on November 29, 1932.[Stein, George H. (1962]

Russo-German Military Collaboration: The Last Phase, 1933

''Political Science Quarterly

''Political Science Quarterly'' is an American double blind peer-reviewed academic journal covering government, politics, and policy, published since 1886 by the Academy of Political Science. Its editor-in-chief is Robert Y. Shapiro (Columbia U ...

'' 77 (1), 54–71.

The conflict between the Communist Party of Germany and the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been ...

fundamentally contributed to the demise of the Weimar Republic. It is, however, disputed whether Hitler's seizure of power came as a surprise to the USSR. Some authors claim that Stalin deliberately aided Hitler's rise by directing the policy of the Communist Party of Germany on a suicidal course in order to foster an inter-imperialist war, a theory dismissed by many others.

During this period, trade between Germany and the Soviet Union declined as the more isolationist Stalinist regime asserted its power and as the abandonment of post-World War I military control decreased Germany's reliance on Soviet imports,

Persecution of ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union

The USSR had a large population of ethnic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

, especially in the , who were distrusted and persecuted by Stalin 1928 to 1948. They were relatively well-educated, and at first, class factors played a major role, giving way after 1933 to ethnic links to the dreaded Nazi German regime as the chief criterion. Taxes escalated after the Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

. Some settlements were permanently banished to the east of the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

.

Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union before World War II

German documents pertaining to Soviet-German relations were captured by the American and British armies in 1945, and published by the U.S. Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

shortly thereafter. In the Soviet Union and Russia, including in official speeches and historiography, Nazi Germany has generally been referred to as Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

Germany (russian: фашистская Германия) from 1933 until today.

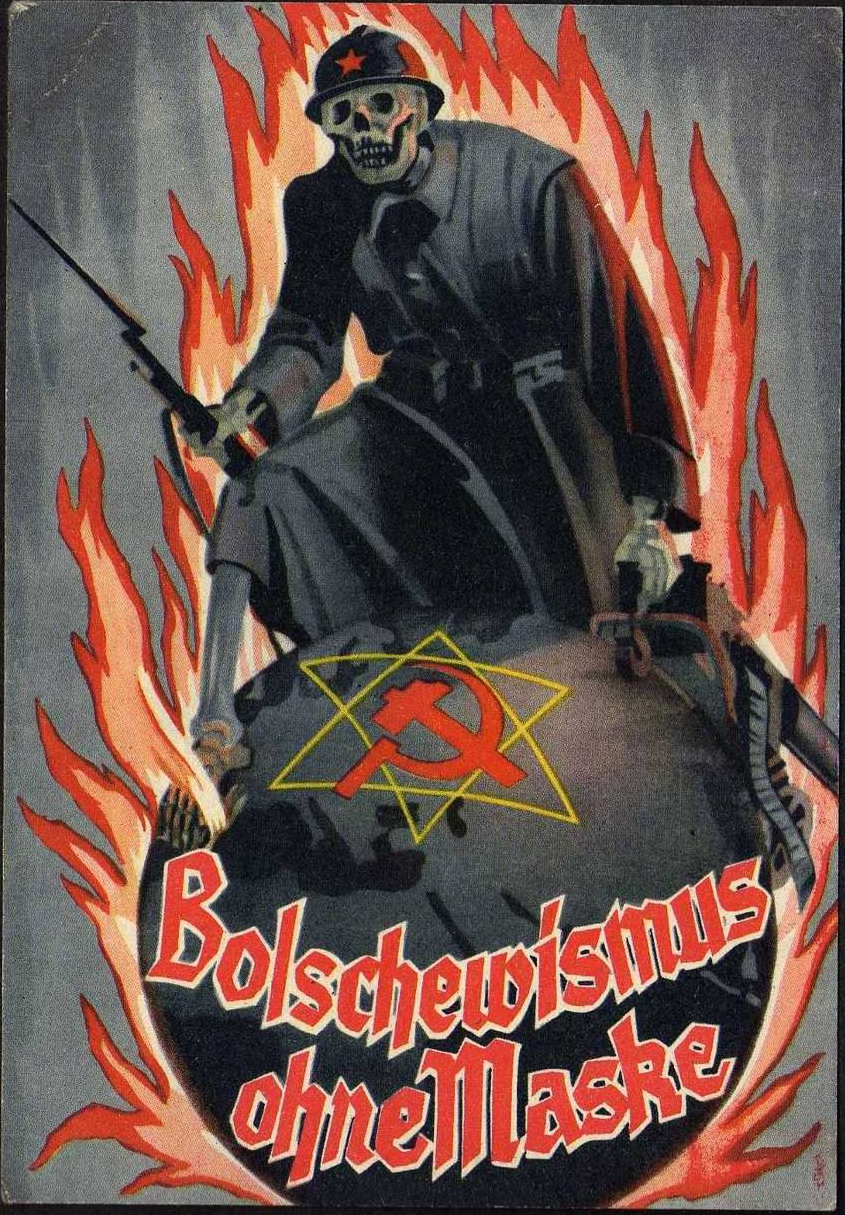

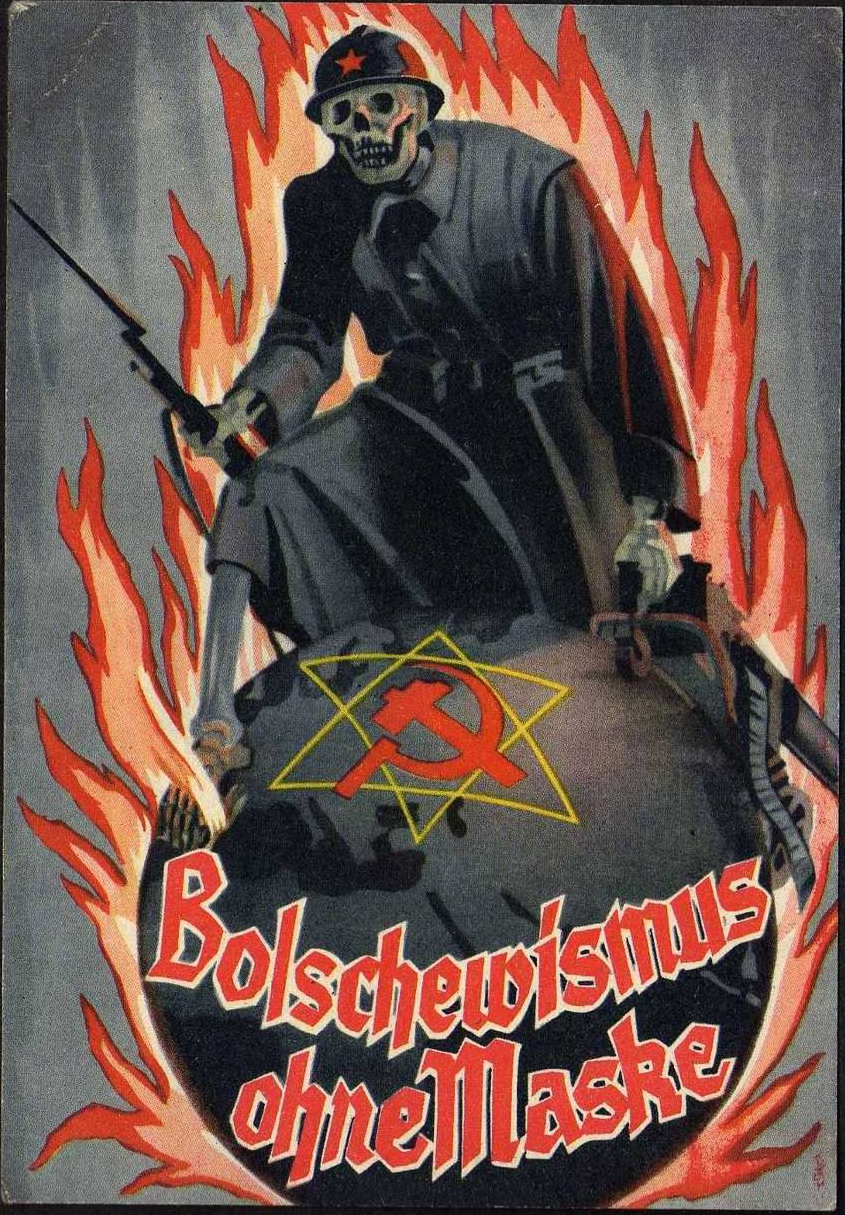

Initial relations after Hitler's election

After

After Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

came to power on January 30, 1933, he began the suppression of the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

. The Nazis took police measures against Soviet trade missions, companies, press representatives, and individual citizens in Germany. They also launched an anti-Soviet propaganda campaign coupled with a lack of good will in diplomatic relations, although the German Foreign Ministry

The Federal Foreign Office (german: Auswärtiges Amt, ), abbreviated AA, is the foreign ministry of the Federal Republic of Germany, a federal agency responsible for both the country's foreign policy and its relationship with the European Union. ...

under Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his di ...

(foreign minister from 1932 to 1938) was vigorously opposed to the impending breakup.Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Ge ...

(which first appeared in 1926) called for ''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

'' (living space for the German nation) in the east (mentioning Russia specifically), and, in keeping with his world view, portrayed the Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

as Jews (see also Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, which alleges that the Jews were the originators of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and that they held primary power among the Bolsheviks who led the revo ...

) who were destroying a great nation.

Moscow's reaction to these steps of Berlin was initially restrained, with the exception of several tentative attacks on the new German government in the Soviet press. However, as the heavy-handed anti-Soviet actions of the German government continued unabated, the Soviets unleashed their own propaganda campaign against the Nazis, but by May the possibility of conflict appeared to have receded. The 1931 extension of the Berlin Treaty was ratified in Germany on May 5.[Haslam, ''The Soviet Union and the Struggle'', p. 22.] However, Reichswehr access to the three military training and testing sites (Lipetsk, Kama, and Tomka) was abruptly terminated by the Soviet Union in August–September 1933.Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

.[Carr, E. H. (1949]

From Munich to Moscow. I

''Soviet Studies'' 1 (1), 3–17.

Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

, who had been People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs (Foreign Minister of the USSR) since 1930, considered Nazi Germany to be the greatest threat to the Soviet Union. However, as the Red Army was perceived as not strong enough, and the USSR sought to avoid becoming embroiled in a general European war, he began pursuing a policy of collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats ...

, trying to contain Nazi Germany via cooperation with the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

and the Western Powers. The Soviet attitude towards the League of Nations and international peace had changed. In 1933–34 the Soviet Union was diplomatically recognized for the first time by Spain, the United States, Hungary, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, and ultimately joined the League of Nations in September 1934. It is often argued that the change in Soviet foreign policy happened around 1933–34, and that it was triggered by Hitler's assumption of power. However, the Soviet turn towards the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

in 1932, discussed above, could also have been a part of the policy change.Hermann Rauschning

Hermann Adolf Reinhold Rauschning (7 August 1887 – February 8, 1982) was a German politician and author, adherent of the Conservative Revolution movement who briefly joined the Nazi movement before breaking with it. He was the President of the ...

in his 1940 book ''Hitler Speaks: A Series of Political Conversations With Adolf Hitler on His Real Aims 1934'' records Adolf Hitler as speaking of an inescapable battle against both Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rule ...

and Neo-Slavism. The authenticity of the book is controversial: some historians, such as Wolfgang Hänel, claim that the book is a fabrication, whereas others, such as Richard Steigmann-Gall

Richard Steigmann-Gall (Born October 3, 1965) is an Associate Professor of History at Kent State University, and the former Director of the Jewish Studies Program from 2004 to 2010.

Education

He received his BA in history in 1989 and MA ...

, Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's leading experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is pa ...

and Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Roper was a polemicist and essayist on a range of ...

, have avoided using it as a reference due to its questionable authenticity. Rauschning records Hitler as saying of the Slavs:

Relations in the mid-1930s

On May 2, 1935, France and the USSR signed a five-year

On May 2, 1935, France and the USSR signed a five-year Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance

The Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance was a bilateral treaty between France and the Soviet Union with the aim of enveloping Nazi Germany in 1935 to reduce the threat from Central Europe. It was pursued by Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet forei ...

. France's ratification of the treaty provided one of the reasons why Hitler remilitarized the Rhineland on March 7, 1936.

The 7th World Congress of the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

in 1935 officially endorsed the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

strategy of forming broad alliances with parties willing to oppose fascism – Communist parties had started pursuing this policy from 1934. Also in 1935, at the 7th Congress of Soviets

The Congress of Soviets was the supreme governing body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and several other Soviet republics from 1917 to 1936 and a somewhat similar Congress of People's Deputies from 1989 to 1991. After the cre ...

(in a study in contradiction), Molotov stressed the need for good relations with Berlin.

On November 25, 1936, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

concluded the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

, which Fascist Italy joined in 1937.

Economically, the Soviet Union made repeated efforts to reestablish closer contacts with Germany in the mid-1930s.Four Year Plan

The Four Year Plan was a series of economic measures initiated by Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany in 1936. Hitler placed Hermann Göring in charge of these measures, making him a Reich Plenipotentiary (Reichsbevollmächtigter) whose jurisdiction cut a ...

for rearmament "without regard to costs". However, despite those issues, Hitler rebuffed the Soviet Union's attempts to seek closer political ties to Germany along with an additional credit agreement.Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

in Britain, who dominated the House of Commons from 1931 onwards, continued to regard the Soviet Union as no less of a threat than Nazi Germany (some saw the USSR as the greater threat). At the same time, as the Soviet Union underwent upheavals in the midst of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

of 1934–1940, the West did not perceive it as a potentially valuable ally.purge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertak ...

of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs The People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs (NKID or the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs) was the state body of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the USSR and the Soviet Union responsible for conducting the foreign policy of ...

forced the Soviet Union to close down quite a number of embassies abroad. At the same time, the purges made the signing of an economic deal with Germany less likely: they disrupted the already confused Soviet administrative structure necessary for negotiations and thus prompted Hitler to regard the Soviets as militarily weak.

Spanish Civil War

The Nationalists led by General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

defeated the Republican government for control of Spain in a very bloody civil war, 1936–1939. Germany sent in elite air and tank units to the Nationalist forces; and Italy sent in several combat divisions. The Soviet Union sent military and political advisors, and sold munitions in support of the "Loyalist," or Republican, side. The Comnitern helped Communist parties around the world send in volunteers to the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed ...

that fought for the Loyalists. The other major powers were neutral.

Collective security failures

Litvinov's policy of containing Germany via collective security failed utterly with the conclusion of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

on September 29, 1938, when Britain and France favored self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It sta ...

of the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

over Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

's territorial integrity

Territorial integrity is the principle under international law that gives the right to sovereign states to defend their borders and all territory in them of another state. It is enshrined in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and has been recognized ...

, disregarding the Soviet position. However, it is still disputed whether, even before Munich, the Soviet Union would actually have fulfilled its guarantees to Czechoslovakia, in the case of an actual German invasion resisted by France.[Hochman, Jiri. ''The Soviet Union and the Failure of Collective Security, 1934–1938''. London – Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1984.]

In April 1939, Litvinov launched the tripartite alliance negotiations with the new British and French ambassadors, (William Seeds

Sir William Seeds KCMG (27 June 1882 – 2 November 1973) was a British diplomat who served as ambassador to both the Soviet Union and Brazil.

Background and education

Seeds was born in Dublin, Ireland, on 27 June 1882, to an Ulster Pro ...

, assisted by William Strang

William Strang (13 February 1859 – 12 April 1921) was a Scottish painter and printmaker, notable for illustrating the works of Bunyan, Coleridge and Kipling.

Early life

Strang was born at Dumbarton, the son of Peter Strang, a builder, a ...

, and Paul-Emile Naggiar), in an attempt to contain Germany. However, they were constantly dragged out and proceeded with major delays.

The Western powers believed that war could still be avoided and the USSR, much weakened by the purges, could not act as a main military participant. The USSR more or less disagreed with them on both issues, approaching the negotiations with caution because of the traditional hostility of the capitalist powers.[Watson, Derek (2000)]

Molotov's Apprenticeship in Foreign Policy: The Triple Alliance Negotiations in 1939

''Europe-Asia Studies'' 52.4, 695–722.[Resis, Albert (2000)]

The Fall of Litvinov: Harbinger of the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact

''Europe-Asia Studies'' 52 (1), 33–56. The Soviet Union also engaged in secret talks with Nazi Germany, while conducting official ones with United Kingdom and France.[''Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War 1917–1991'' by Robert C. Grogin. 2001, Lexington Books page 28] From the beginning of the negotiations with France and Britain, the Soviets demanded that Finland be included in the Soviet sphere of influence.["Scandinavia and the Great Powers 1890–1940" Patrick Salmon 2002 Cambridge University Press]

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

1939 needs and discussions

By the late 1930s, because a German autarkic

Autarky is the characteristic of self-sufficiency, usually applied to societies, communities, states, and their economic systems.

Autarky as an ideal or method has been embraced by a wide range of political ideologies and movements, especially ...

economic approach or an alliance with Britain was impossible, closer relations with the Soviet Union were necessary, if not just for economic reasons alone.Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

, who had strained relations with Litvinov, was not of Jewish origin (unlike Litvinov), and had always been in favour of neutrality towards Germany, was put in charge of foreign affairs. The Foreign Affairs Commissariat was purged of Litvinov's supporters and Jews.[Haslam, Jonathan (1997)]

Review: Soviet-German Relations and the Origins of the Second World War: The Jury Is Still Out

''The Journal of Modern History

''The Journal of Modern History'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering European intellectual, political, and cultural history, published by the University of Chicago Press. Established in 1929, the journal covers events from app ...

'' 69.4, 785–797.[Roberts, Geoffrey. ''Unholy Alliance'' (1989)]

Additional factors that drove the Soviet Union towards a rapprochement with Germany might be the signing of a non-aggression pact between Germany, Latvia and Estonia on June 7, 1939 and the threat from Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

in the East, as evidenced by the Battle of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, ...

(May 11 – September 16, 1939). Molotov suggested that the Japanese attack might have been inspired by Germany in order to hinder the conclusion of the tripartite alliance.[Watson, Derek (2000)]

Molotov's Apprenticeship in Foreign Policy: The Triple Alliance Negotiations in 1939

''Europe-Asia Studies'' 52 (4), 695–722.

In July, open Soviet–German trade negotiations were under way.Joachim Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's n ...

outlined a plan in which Germany and the Soviet Union would agree to nonintervention in each other's affairs and would renounce measures aimed at the other's vital interests[Fest, Joachim C., ''Hitler'', Harcourt Brace Publishing, 2002 , pp. 589–90] The Germans stated that "there is one common element in the ideology of Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union: opposition to the capitalist democracies of the West",Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

and with the Soviet renunciation of a world revolution.

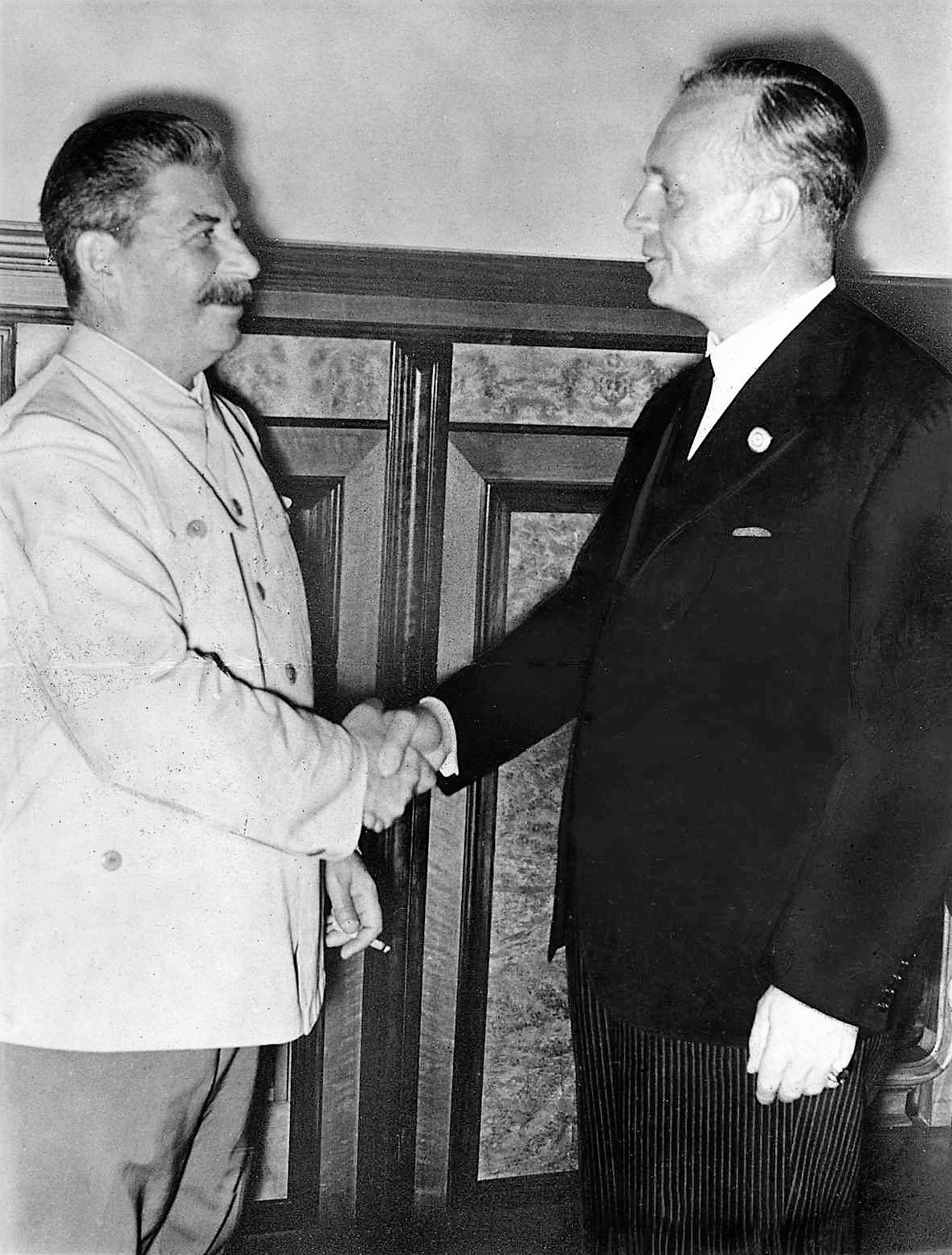

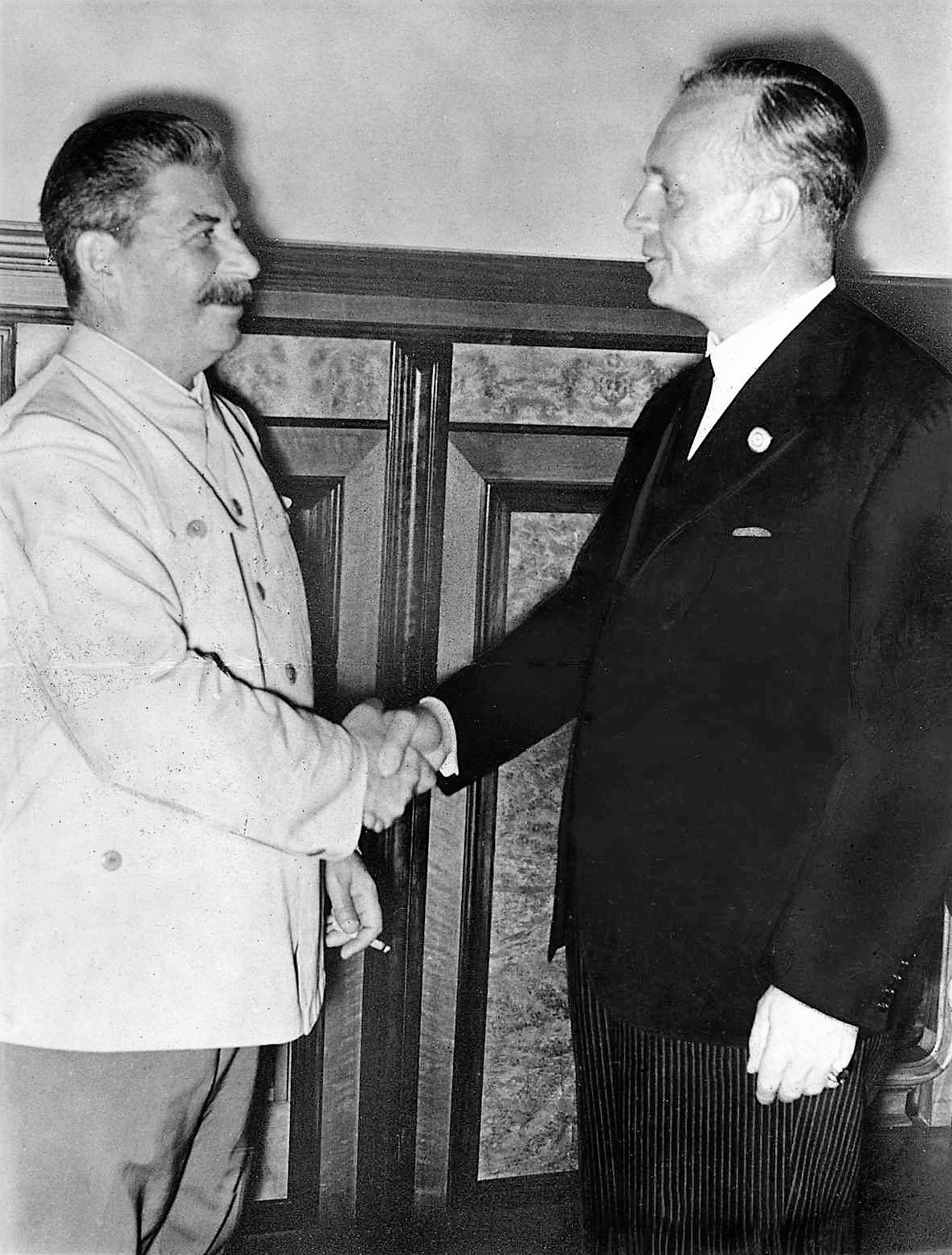

Pact and commercial deal signings

By August 10, the countries had worked out the last minor technical details to make all but final their economic arrangement, but the Soviets delayed signing that agreement for almost ten days until they were sure that they had reached a political agreement with Germany.

By August 10, the countries had worked out the last minor technical details to make all but final their economic arrangement, but the Soviets delayed signing that agreement for almost ten days until they were sure that they had reached a political agreement with Germany.Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

arrived to Moscow, and in the following night, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

was signed by him and his Soviet colleague Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

, in the presence of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. The ten-year pact of non-aggression declared both parties' continued adherence to the Treaty of Berlin (1926)

The Treaty of Berlin (German-Soviet Neutrality and Nonaggression Pact) was a treaty signed on 24 April 1926 under which Germany and the Soviet Union pledged neutrality in the event of an attack on the other by a third party for five years. The ...

, but the pact was also supplemented by a secret additional protocol, which divided Eastern Europe into German and Soviet zones of influence:

1. In the event of a territorial and political rearrangement in the areas belonging to the Baltic States (Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

, Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

), the northern boundary of Lithuania shall represent the boundary of the spheres of influence of Germany and the U.S.S.R. In this connection the interest of Lithuania in the Vilna area is recognized by each party.

2. In the event of a territorial and political rearrangement of the areas belonging to the Polish state

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

the spheres of influence of Germany and the U.S.S.R. shall be bounded approximately by the line of the rivers Narew

The Narew (; be, Нараў, translit=Naraŭ; or ; Sudovian: ''Naura''; Old German: ''Nare''; uk, Нарва, translit=Narva) is a 499-kilometre (310 mi) river primarily in north-eastern Poland, which is also a tributary of the river Vi ...

, Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

, and San.

The question of whether the interests of both parties make desirable the maintenance of an independent Polish state and how such a state should be bounded can only be definitely determined in the course of further political developments.

In any event both Governments will resolve this question by means of a friendly agreement.

3. With regard to Southeastern Europe attention is called by the Soviet side to its interest in Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

. The German side declares its complete political disinterestedness in these areas.

The secret protocol shall be treated by both parties as strictly secret.[''Text of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact''](_blank)

executed August 23, 1939

Though the parties denied its existence,[Biskupski, Mieczysław B. and Piotr Stefan Wandycz, ''Ideology, Politics, and Diplomacy in East Central Europe'', Boydell & Brewer, 2003, , pages 147] the protocol was rumored to exist from the very beginning.[Sontag, Raymond James & James Stuart Beddie. ''Nazi-Soviet Relations 1939–1941: Documents from the Archives of The German Foreign Office''. Washington, D.C.: Department of State, 1948. P. 78.]

The news of the Pact, which was announced by ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' and ''Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, and describes i ...

'' on August 24, was met with utter shock and surprise by government leaders and media worldwide, most of whom were aware of only the British-French-Soviet negotiations, which had taken place for months.Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( rus, Верховный Совет Союза Советских Социалистических Республик, r=Verkhovnyy Sovet Soyuza Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respubl ...

on August 31, 1939.

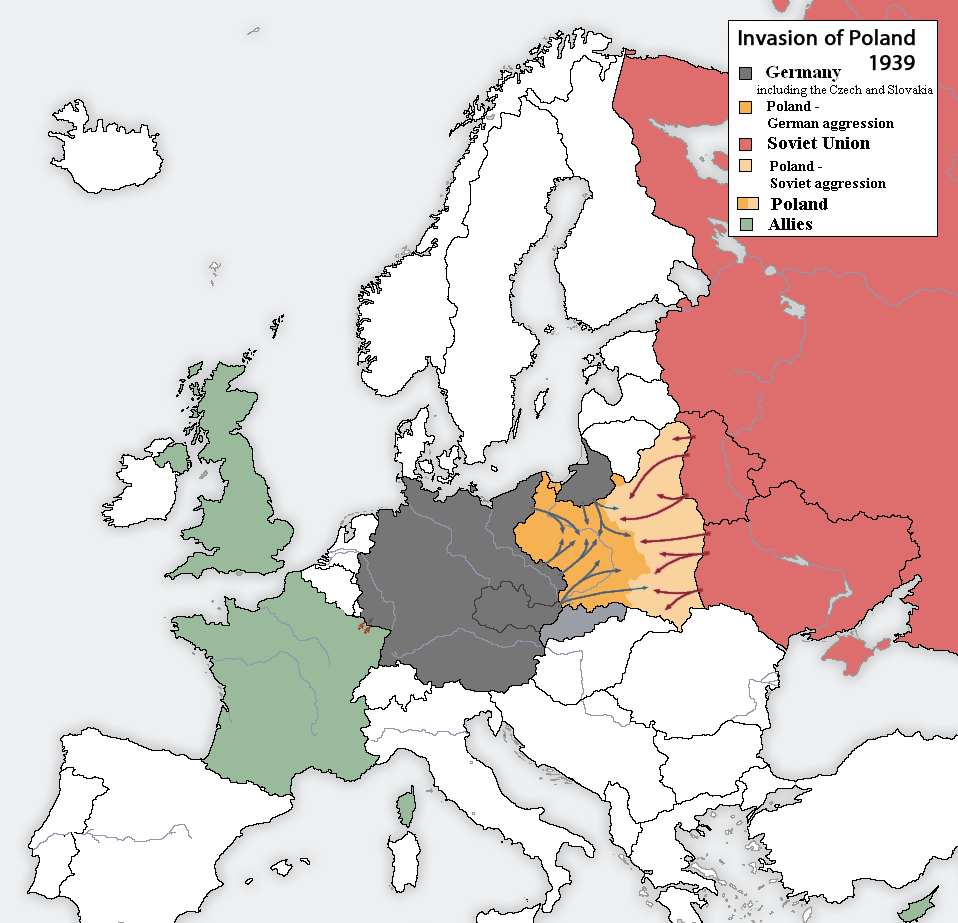

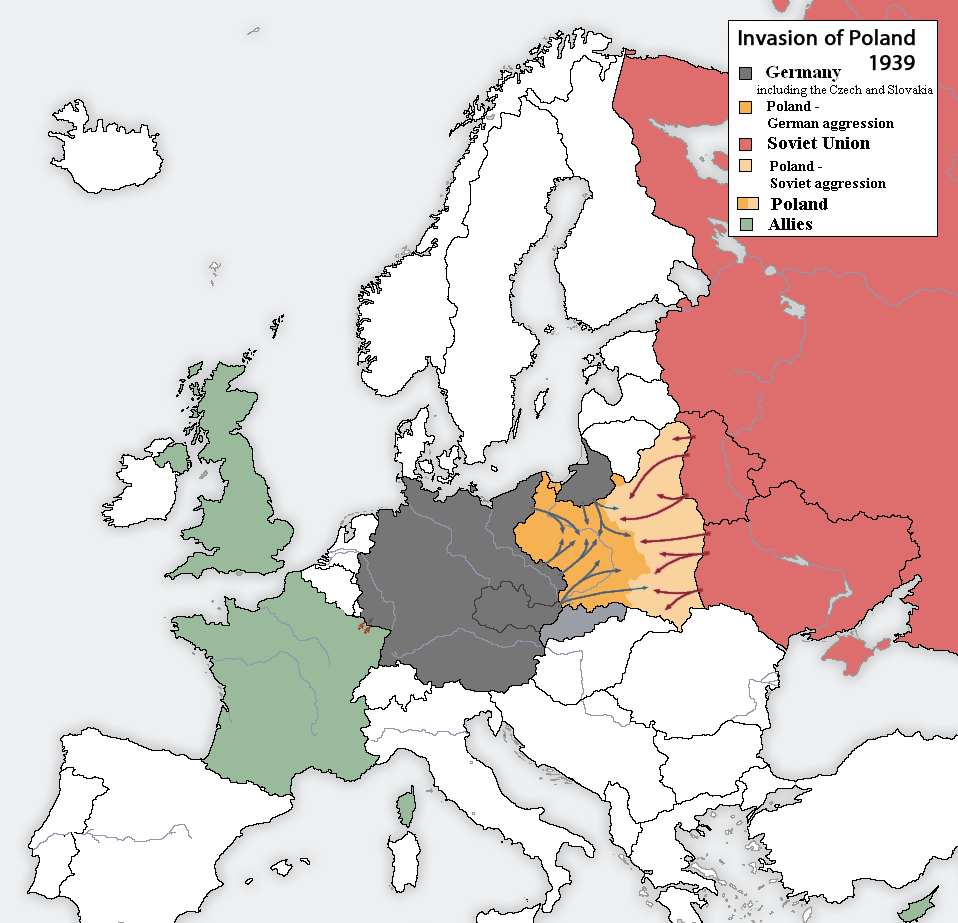

World War II

German invasion of western Poland

A week after having signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, on September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded its zone of influence in Poland. On September 3, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and France, fulfilling their obligations to the

A week after having signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, on September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded its zone of influence in Poland. On September 3, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and France, fulfilling their obligations to the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

, declared war on Germany. The Second World War broke out in Europe.

On September 4, as Britain blockaded Germany at sea, German cargo ships heading towards German ports were diverted to the Soviet Arctic port of Murmansk. On September 8 the Soviet side agreed to pass it by railway to the Soviet Baltic Sea port of Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. At the same time the Soviet Union refused to allow a Polish transit through its territory citing the threat of being drawn into war on September 5.

Von der Schulenburg reported to Berlin that attacks on the conduct of Germany in the Soviet press had ceased completely and the portrayal of events in the field of foreign politics largely coincided with the German point of view, while anti-German literature had been removed from the trade.

On September 7 Stalin once again outlined a new line for the Comintern that was now based on the idea that the war was an inter-imperialist conflict and hence there was no reason for the working class to side with Britain, France, or Poland against Germany, thus departing from the Comintern's anti-fascist popular front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

policy of 1934–1939.[Roberts, Geoffrey (1992)]

The Soviet Decision for a Pact with Nazi Germany

''Soviet Studies'' 44 (1), 57–78. He labeled Poland as a fascist state oppressing Belarusians and Ukrainians.

German diplomats had urged the Soviet Union to intervene against Poland from the east since the beginning of the war,Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg

Friedrich-Werner Erdmann Matthias Johann Bernhard Erich Graf von der Schulenburg (20 November 1875 – 10 November 1944) was a German diplomat who served as the last German ambassador to the Soviet Union before Operation Barbarossa, the Germa ...

on September 9, but the actual invasion was delayed for more than a week.

Soviet invasion of eastern Poland