German Occupation Of Denmark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the outset of

At the outset of

The military occupation, occupation of Denmark was initially not an important objective for the German government. The decision to occupy its small northern neighbour was taken to facilitate a planned invasion of the strategically more important

The military occupation, occupation of Denmark was initially not an important objective for the German government. The decision to occupy its small northern neighbour was taken to facilitate a planned invasion of the strategically more important  As a result of the rapid turn of events, the Danish government did not have enough time to officially declare war on Germany. Denmark was in an untenable position in any event, however. Its territory and population were too small to hold out against Germany for any sustained period. Its flat land would have resulted in it being easily overrun by German

As a result of the rapid turn of events, the Danish government did not have enough time to officially declare war on Germany. Denmark was in an untenable position in any event, however. Its territory and population were too small to hold out against Germany for any sustained period. Its flat land would have resulted in it being easily overrun by German  Sixteen Danish soldiers died in the invasion, but after two hours the Danish government surrendered, believing that resistance was useless and hoping to work out an advantageous agreement with Germany. The flat territory of Jutland was a perfect area for the German army to operate in, and the surprise attack on Copenhagen had made any attempt to defend

Sixteen Danish soldiers died in the invasion, but after two hours the Danish government surrendered, believing that resistance was useless and hoping to work out an advantageous agreement with Germany. The flat territory of Jutland was a perfect area for the German army to operate in, and the surprise attack on Copenhagen had made any attempt to defend

Historically, Denmark had a large amount of interaction with Germany. In 1920 the country regained possession of the northern part of

Historically, Denmark had a large amount of interaction with Germany. In 1920 the country regained possession of the northern part of  Stauning remained

Stauning remained  The Danish authorities were able to use their more cooperative stance to win important concessions for the country. They continually refused to enter a

The Danish authorities were able to use their more cooperative stance to win important concessions for the country. They continually refused to enter a

According to Danish law, it was not illegal to join a foreign army, but active recruiting on Danish soil was illegal. The SS disregarded this law and began recruiting efforts – predominantly recruiting Danish Nazis and members of the German-speaking minority. The Danish government discovered this and decided to concentrate on persuading the Germans not to recruit underage boys. General Prior wanted to remove Kryssing and his designated second-in-command but decided to consult the cabinet. It agreed that Kryssing should be removed in its meeting on 2 July 1941, but this decision was later withdrawn when Erik Scavenius—who had not attended the original meeting—returned from negotiations and announced that he had reached an agreement with Renthe-Fink that soldiers wishing to join this corps could be given leave until further notice. The government issued an announcement stating that "Lieut. Colonel C.P. Kryssing, Chief of the 5th Artillery reg., Holbæk, has with the consent of the Royal Danish Government assumed command over 'Free Corps Denmark'". The Danish text only explicitly said that the government recognized that Kryssing had been given a new command; it did not sanction the creation of the corps, which had already happened without its creators asking the government's consent. In July 1941

According to Danish law, it was not illegal to join a foreign army, but active recruiting on Danish soil was illegal. The SS disregarded this law and began recruiting efforts – predominantly recruiting Danish Nazis and members of the German-speaking minority. The Danish government discovered this and decided to concentrate on persuading the Germans not to recruit underage boys. General Prior wanted to remove Kryssing and his designated second-in-command but decided to consult the cabinet. It agreed that Kryssing should be removed in its meeting on 2 July 1941, but this decision was later withdrawn when Erik Scavenius—who had not attended the original meeting—returned from negotiations and announced that he had reached an agreement with Renthe-Fink that soldiers wishing to join this corps could be given leave until further notice. The government issued an announcement stating that "Lieut. Colonel C.P. Kryssing, Chief of the 5th Artillery reg., Holbæk, has with the consent of the Royal Danish Government assumed command over 'Free Corps Denmark'". The Danish text only explicitly said that the government recognized that Kryssing had been given a new command; it did not sanction the creation of the corps, which had already happened without its creators asking the government's consent. In July 1941

The Danish government refused, so on 29 August 1943 the Germans officially dissolved the Danish government and instituted

The Danish government refused, so on 29 August 1943 the Germans officially dissolved the Danish government and instituted  In anticipation of

In anticipation of  In September 1943, a variety of resistance groups grouped together in the Danish Freedom Council, which coordinated resistance activities. A high-profile resister was former government minister

In September 1943, a variety of resistance groups grouped together in the Danish Freedom Council, which coordinated resistance activities. A high-profile resister was former government minister

.

After the fall of the government, Denmark was exposed to the full extent of occupational rule. In October the Germans decided to remove all Jews from Denmark, but thanks to an information leak from German diplomat Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz and swift action by Danish civilians, the vast majority of the Danish Jews were transported to safety in neutral Sweden by means of fishing boats and motorboats. The entire evacuation lasted two months and one man helped ferry more than 1,400 Jews to safety. Unencumbered by government opposition,

, 5 October 2011, Nationalbanken. Accessed 14 December 2012. The law required was passed hastily on Friday 20 July and published the same day; it also closed all shops for the weekend. By Monday 23 July, all old notes were officially outlawed as legal tender and any note not declared in a bank by 30 July would lose its value. This law allowed any Dane to exchange a total of 100 kroner to new notes, no questions asked. An amount up to 500 kroner would be exchanged, provided the owner signed a written statement explaining its origins. Any amount above this level would be deposited in an

Most of Denmark was liberated from German rule in May 1945 by British forces commanded by Field Marshal

Most of Denmark was liberated from German rule in May 1945 by British forces commanded by Field Marshal  Although Denmark was spared many of the difficulties other areas of Europe suffered, its population still experienced hardships, particularly after the Germans took charge in 1943. Yet on the whole, Denmark can be said to have suffered the least of all the European combatants from the war. Many were killed and imprisoned because of their work resisting the German authorities. There were small bombing raids on select targets in the country, but nothing comparable to that suffered by, for instance, neighbouring Norway or the Netherlands. One area that was badly damaged was the island of

Although Denmark was spared many of the difficulties other areas of Europe suffered, its population still experienced hardships, particularly after the Germans took charge in 1943. Yet on the whole, Denmark can be said to have suffered the least of all the European combatants from the war. Many were killed and imprisoned because of their work resisting the German authorities. There were small bombing raids on select targets in the country, but nothing comparable to that suffered by, for instance, neighbouring Norway or the Netherlands. One area that was badly damaged was the island of  Approximately 6,000 Danes were sent to concentration camps during World War II, of whom about 600 (10%) died. In comparison with other countries this is a relatively low mortality rate in the concentration camps.

After the war, 40,000 people were arrested on suspicion of

Approximately 6,000 Danes were sent to concentration camps during World War II, of whom about 600 (10%) died. In comparison with other countries this is a relatively low mortality rate in the concentration camps.

After the war, 40,000 people were arrested on suspicion of  After the end of hostilities, over two thousand German prisoners of war were made to clear the vast minefields that had been laid on the west coast of Jutland, nearly half of them being either killed or wounded in the process. As part of a controversial agreement reached by the German Commander General

After the end of hostilities, over two thousand German prisoners of war were made to clear the vast minefields that had been laid on the west coast of Jutland, nearly half of them being either killed or wounded in the process. As part of a controversial agreement reached by the German Commander General

The policy of the government, called ''samarbejdspolitikken'' (cooperation policy) is one of the most controversial issues in Danish history. Some historians argue that the relatively accommodating policy which did not actively resist the occupation was the only realistic way of safeguarding Danish democracy and people. However, others argue that accommodation was taken too far, was uniquely compliant when compared to other democratic governments in Europe, and cannot be seen as part of a coherent long-term strategy to protect democracy in Denmark or Europe. In 2003 Danish Prime Minister

The policy of the government, called ''samarbejdspolitikken'' (cooperation policy) is one of the most controversial issues in Danish history. Some historians argue that the relatively accommodating policy which did not actively resist the occupation was the only realistic way of safeguarding Danish democracy and people. However, others argue that accommodation was taken too far, was uniquely compliant when compared to other democratic governments in Europe, and cannot be seen as part of a coherent long-term strategy to protect democracy in Denmark or Europe. In 2003 Danish Prime Minister

Agreement between U.S. Secretary of State and Danish Minister on the status of Greenland April 10, 1941

The BBC's Danish broadcast, 4 May 1945, 20:30 announcing the surrender of the German army units in Denmark

(audio, RealPlayer)

Podcast with one of 2,000 Danish policemen in Buchenwald.

Episode 2 is about Denmark during World War II.

Besaettelsessamlingen, web museum about Denmark 1940–45

* {{Authority control 1940s in Denmark Denmark–Germany relations German military occupations Jewish Danish history Military history of Denmark during World War II

At the outset of

At the outset of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in September 1939, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

declared itself neutral. For most of the war, the country was a protectorate and then an occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

territory of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. The decision to occupy Denmark was taken in Berlin on 17 December 1939. On 9 April 1940, Germany occupied Denmark in Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung (german: Unternehmen Weserübung , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was Germany's assault on Denmark and Norway during the Second World War and the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 Ap ...

. The Danish government

The Cabinet of Denmark ( da, regering) has been the chief executive body and the government of the Kingdom of Denmark since 1848. The Cabinet is led by the Prime Minister. There are around 25 members of the Cabinet, known as "ministers", all of wh ...

and king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

functioned as relatively normal in a ''de facto'' protectorate over the country until 29 August 1943, when Germany placed Denmark under direct military occupation, which lasted until the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

victory on 5 May 1945. Contrary to the situation in other countries under German occupation, most Danish institutions continued to function relatively normally until 1945. Both the Danish government and king remained in the country in an uneasy relationship between a democratic and a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

system until the Danish government stepped down in a protest against German demands to institute the death penalty for sabotage.

Just over 3,000 Danes died as a direct result of the occupation. A further 2,000 volunteers of Free Corps Denmark

Free Corps Denmark ( da, Frikorps Danmark) was a unit of the Waffen-SS during World War II consisting of collaborationist volunteers from Denmark. It was established following an initiative by the National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark (DNS ...

and Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

, of which most originated from the German minority of southern Denmark, died fighting on the Eastern Front while 1,072 merchant sailors died in Allied service. Overall, this represents a very low mortality rate when compared to other occupied countries and most belligerent countries. Some Danes chose to collaborate during the occupation by joining the National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark

The National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark ( da, Danmarks Nationalsocialistiske Arbejderparti; DNSAP) was the largest Nazi Party in Denmark before and during the Second World War.

History

The party was founded on 16 November 1930, after ...

, Schalburg Corps

The Germanic SS () was the collective name given to paramilitary and political organisations established in parts of German-occupied Europe between 1939 and 1945 under the auspices of the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS). The units were modeled on the '' ...

, HIPO Corps

The HIPO Corps (Danish: HIPO-korpset) was a Danish auxiliary police corps, established by the German Gestapo on 19 September 1944, when the Danish civil police force was disbanded and most of its officers were arrested and deported to concentrat ...

and Peter Group

The Peter group ( Danish: ''Petergruppen'') was a paramilitary group created in late 1943 during the occupation of Denmark by the German occupying power. The group conducted counter-sabotage, also known as Schalburgtage, in response to the Dani ...

(often with considerable overlap between the participants of the different groups). The National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark participated in the 1943 Danish Folketing election, but despite significant support from Germany it only received 2.1% of the votes.

A resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objective ...

developed over the course of the war, and the vast majority of Danish Jews were rescued and sent to neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

in 1943 when German authorities ordered their internment as part of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

br>Invasion

The military occupation, occupation of Denmark was initially not an important objective for the German government. The decision to occupy its small northern neighbour was taken to facilitate a planned invasion of the strategically more important

The military occupation, occupation of Denmark was initially not an important objective for the German government. The decision to occupy its small northern neighbour was taken to facilitate a planned invasion of the strategically more important Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, and as a precaution against the expected British response. German military planners believed that a base in the northern part of Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

, specifically the airfield of Aalborg, would be essential to operations in Norway, and they began planning the occupation of parts of Denmark. However, as late as February 1940 no firm decision to occupy Denmark had been made.Henrik Dethlefsen, "Denmark and the German Occupation: Cooperation, Negotiation, or Collaboration," ''Scandinavian Journal of History''. 15:3 (1990), pp. 193, 201–2. The issue was finally settled when Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

personally crossed out the words ' ("the Northern tip of Jutland") and replaced them with ', a German abbreviation for Denmark.

Although the Danish territory of South Jutland was home to a significant German minority, and the province had been regained from Germany as a result of a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

resulting from the Versailles Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, Germany was in no apparent hurry to reclaim it. In a much more vague and longer-term way, some Nazis hoped to incorporate Denmark into a greater "Nordic Union" at some stage, but these plans never materialized. Officially Germany claimed to be protecting Denmark from a British invasion.Jørgen Hæstrup, ''Secret Alliance: A Study of the Danish Resistance Movement 1940–45''. Odense, 1976. p. 9.

At 4:15 on the morning of 9 April 1940, German forces crossed the border into neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

Denmark. In a coordinated operation, German ships began disembarking troops at the docks in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

. Although outnumbered and poorly equipped, soldiers in several parts of the country offered resistance; most notably the Royal Guard

A royal guard is a group of military bodyguards, soldiers or armed retainers responsible for the protection of a royal person, such as the emperor or empress, king or queen, or prince or princess. They often are an elite unit of the regular arm ...

in Copenhagen and units in South Jutland. At the same time as the border crossing, German planes dropped the notorious leaflets over Copenhagen calling on Danes to accept the German occupation peacefully, and claiming that Germany had occupied Denmark in order to protect it against Great Britain and France. Colonel Lunding from the Danish army

The Royal Danish Army ( da, Hæren, fo, Herurin, kl, Sakkutuut) is the land-based branch of the Danish Defence, together with the Danish Home Guard. For the last decade, the Royal Danish Army has undergone a massive transformation of structures ...

's intelligence office later confirmed that Danish intelligence knew the attack would be coming on either 8 or 9 April and had warned the government accordingly. The Danish ambassador to Germany, Herluf Zahle, issued a similar warning which was also ignored.

As a result of the rapid turn of events, the Danish government did not have enough time to officially declare war on Germany. Denmark was in an untenable position in any event, however. Its territory and population were too small to hold out against Germany for any sustained period. Its flat land would have resulted in it being easily overrun by German

As a result of the rapid turn of events, the Danish government did not have enough time to officially declare war on Germany. Denmark was in an untenable position in any event, however. Its territory and population were too small to hold out against Germany for any sustained period. Its flat land would have resulted in it being easily overrun by German panzer

This article deals with the tanks (german: panzer) serving in the German Army (''Deutsches Heer'') throughout history, such as the World War I tanks of the Imperial German Army, the interwar and World War II tanks of the Nazi German Wehrmacht, ...

s; Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

, for instance, was immediately adjacent to to the south and was thus wide open to a panzer attack from there. Unlike Norway, Denmark had no mountain ranges from which a drawn-out resistance could be mounted.William Shirer, ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'' (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), p. 663.

Sixteen Danish soldiers died in the invasion, but after two hours the Danish government surrendered, believing that resistance was useless and hoping to work out an advantageous agreement with Germany. The flat territory of Jutland was a perfect area for the German army to operate in, and the surprise attack on Copenhagen had made any attempt to defend

Sixteen Danish soldiers died in the invasion, but after two hours the Danish government surrendered, believing that resistance was useless and hoping to work out an advantageous agreement with Germany. The flat territory of Jutland was a perfect area for the German army to operate in, and the surprise attack on Copenhagen had made any attempt to defend Zealand

Zealand ( da, Sjælland ) at 7,031 km2 is the largest and most populous island in Denmark proper (thus excluding Greenland and Disko Island, which are larger in size). Zealand had a population of 2,319,705 on 1 January 2020.

It is the 1 ...

impossible. The Germans had also been quick to establish control over the bridge across the Little Belt

The Little Belt (, ) is a strait between the island of Funen and the Jutland Peninsula in Denmark. It is one of the three Danish Straits that drain and connect the Baltic Sea to the Kattegat strait, which drains west to the North Sea and Atlant ...

, thus gaining access to the island of Funen

Funen ( da, Fyn, ), with an area of , is the third-largest island of Denmark, after Zealand and Vendsyssel-Thy. It is the 165th-largest island in the world. It is located in the central part of the country and has a population of 469,947 as of ...

. Believing that further resistance would only result in the futile loss of still more Danish lives, the Danish cabinet ultimately decided to bow to the German pressure "under protest". The German forces were technologically sophisticated and numerous; the Danish forces comparatively tiny and used obsolete equipment; partially a result of a pre-war policy of trying to avoid antagonizing Germany by supplying the army with modern equipment. Even stiff resistance from the Danes would not have lasted long. Questions have been raised around the apparent fact that the German forces did not seem to expect any resistance, invading with unarmored ships and vehicles.

Faroe Islands

After the occupation of Denmark, British forces from 12 April 1940 made a pre-emptive bloodless invasion of theFaroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

to prevent their occupation by German troops. Britain took over the areas where Denmark previously had given support, and the islands now became dependent on the United Kingdom, which began to participate in fishing production and supplied the islands with important goods.

The British fortified positions in strategically important places. Sounds and fjords were mined, and at the island of Vágar

Vágar ( da, Vågø) is one of the 18 islands in the archipelago of the Faroe Islands and the most westerly of the ''large islands''. With a size of , it ranks number three, behind Streymoy and Eysturoy. Vágar region also comprises the island ...

, British engineers built a military aviation base. Up to 8,000 British soldiers were stationed in the Faroe Islands, which at that time had 30,000 inhabitants.

The Faroe Islands were repeatedly attacked by German aircraft, but with minimal damage. However, 25 Faroese ships were lost and 132 sailors died, corresponding to approx. 0.4% of the then Faroese population.

Iceland

From 1918 until 1944Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

was self-governing, but the Danish king (King Christian X) was the head of state of both Denmark and Iceland. The United Kingdom occupied Iceland on 10 May 1940 to pre-empt a German occupation, turning it over to the then neutral United States in July 1941, before the latter's entry into the war in December 1941. Officially remaining neutral throughout World War II, Iceland became a fully independent republic on 17 June 1944.

Greenland

On 9 April 1941, the Danish envoy to the United States,Henrik Kauffmann

Henrik Kauffmann (26 August 1888 – 5 June 1963) was the Danish ambassador to the United States during World War II, who signed over part of Greenland to the US.

Career

Kauffmann started his foreign career by serving as envoy in Rome, 1921� ...

, signed a treaty with the U.S., authorizing it to defend Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

and construct military stations there. Kauffmann was supported in this decision by the Danish diplomats in the United States and the local authorities in Greenland. Signing this treaty "in the name of the King" was a clear violation of his diplomatic powers, but Kauffmann argued that he would not receive orders from an occupied Copenhagen.

Protectorate government (1940–43)

Historically, Denmark had a large amount of interaction with Germany. In 1920 the country regained possession of the northern part of

Historically, Denmark had a large amount of interaction with Germany. In 1920 the country regained possession of the northern part of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

after losing the provinces during the Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. T ...

in 1864. The Danish people were divided about what the best policy toward Germany might be. Few were ardent Nazis; some explored the economic possibilities of providing the German occupiers with supplies and goods; others eventually formed resistance groups towards the latter part of the war. The majority of Danes, however, were unwillingly compliant towards the Germans. Due to the relative ease of the occupation and copious amount of dairy products, Denmark earned the nickname ''the Cream Front'' (german: Sahnefront).

As a result of the cooperative attitude of the Danish authorities, German officials claimed that they would "respect Danish sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as neutrality." The German authorities were inclined towards lenient terms with Denmark for several reasons: their only strong interest in Denmark, that of surplus agricultural products

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

, would be supplied by price policy on food rather than by control and restriction (some German records indicate that the German administration had not fully realized this potential before the occupation took place, which can be doubted);

there was serious concern that the Danish economy was so dependent upon trade with Britain that the occupation would create an economic collapse, and Danish officials capitalized on that fear to get early concessions for a reasonable form of cooperation;

they also hoped to score propaganda points by making Denmark, in Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

's words, "a model protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

";

on top of these more practical goals, Nazi race ideology held that Danes were "fellow Nordic Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

s," and could therefore to some extent be trusted to handle their domestic affairs.

These factors combined to allow Denmark a very favourable relationship with Nazi Germany. The government remained somewhat intact, and the parliament continued to function more or less as it had before. They were able to maintain much of their former control over domestic policy.Phil Giltner, "The Success of Collaboration: Denmark’s Self-Assessment of its Economic Position after Five Years of Nazi Occupation," in ''Journal of Contemporary History'' 36:3 (2001) pp. 486, 488. The police and judicial system

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

remained in Danish hands, and unlike most occupied countries, King Christian X

Christian X ( da, Christian Carl Frederik Albert Alexander Vilhelm; 26 September 1870 – 20 April 1947) was List of Danish monarchs, King of Denmark from 1912 to his death in 1947, and the only List of rulers of Iceland, King of Iceland as ...

remained in the country as Danish head of state. The German Reich was formally represented by a ' ('Reich

''Reich'' (; ) is a German language, German noun whose meaning is analogous to the meaning of the English word "realm"; this is not to be confused with the German adjective "reich" which means "rich". The terms ' (literally the "realm of an emp ...

Plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word ...

'), i.e. a diplomat accredited to the Sovereign, a post awarded to Cecil von Renthe-Fink

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

*Cecil, Alberta, ...

, the German ambassador, and then in November 1942 to the lawyer and SS general Werner Best

Karl Rudolf Werner Best (10 July 1903 – 23 June 1989) was a German jurist, police chief, SS-''Obergruppenführer'', Nazi Party leader, and theoretician from Darmstadt. He was the first chief of Department 1 of the Gestapo, Nazi Germany's secret ...

.

Danish public opinion generally backed the new government, particularly after the fall of France in June 1940.Henning Poulsen, "" ''Historie'' 2 (2000) p. 320. There was a general feeling that the unpleasant reality of German occupation must be confronted in the most realistic way possible, given the international situation. Politicians realized that they would have to try hard to maintain Denmark's privileged position by presenting a united front to the German authorities, so all of the mainstream democratic parties formed a new government together. Parliament and the government agreed to work closely together. Though the effect of this was close to the creation of a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

, it remained a representative government.

The Danish government was dominated by Social Democrat

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

s, including the pre-war prime minister Thorvald Stauning

Thorvald August Marinus Stauning (; 26 October 1873 in Copenhagen – 3 May 1942) was the first social democratic Prime Minister of Denmark. He served as Prime Minister from 1924 to 1926 and again from 1929 until his death in 1942.

Under Stauni ...

, who had been strongly opposed to the Nazi party. Stauning himself was deeply depressed by the prospects for Europe under Nazism. Nonetheless, his party pursued a strategy of cooperation, hoping to maintain democracy and Danish control in Denmark for as long as possible. There were many issues that they had to work out with Germany in the months after the occupation. In an effort to keep the Germans satisfied, they compromised Danish democracy and society in several fundamental ways:

* Newspaper articles and news reports "which might jeopardize German-Danish relations" were outlawed, in violation of the Danish constitutional prohibition against censorship.Voorhis, 1972 pp. 174–6, 179, 181, 183.

* On 22 June 1941 while Germany commenced its attack on the Soviet Union the German authorities in Denmark demanded that Danish communists should be arrested. The Danish government complied and using secret registers, the Danish police in the following days arrested 339 communists. Of these 246, including the three communist members of the Danish parliament, were imprisoned in the Horserød camp

Horserød Camp (also Horserød State Prison, Danish: ''Horserødlejren'' or ''Horserød Statsfængsel'') is an open state prison at Horserød, Denmark located in North Zealand, approximately seven kilometers from Helsingør. Built in 1917, Hor ...

, in violation of the Danish constitution. On 22 August 1941, the Danish parliament (without its communist members) passed the Communist Law, outlawing the communist party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

and communist activities, in another violation of the Danish constitution. In 1943 about half of them were transferred to Stutthof concentration camp

Stutthof was a Nazi concentration camp established by Nazi Germany in a secluded, marshy, and wooded area near the village of Stutthof (now Sztutowo) 34 km (21 mi) east of the city of Danzig (Gdańsk) in the territory of the German-a ...

, where 22 of them died.

* Following Germany's assault on the Soviet Union, Denmark joined the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

, together with the fellow Nordic state of Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

. As a result, many communists were found among the first members of the Danish resistance movement

The Danish resistance movements ( da, Den danske modstandsbevægelse) were an underground insurgency to resist the German occupation of Denmark during World War II. Due to the initially lenient arrangements, in which the Nazi occupation autho ...

.

* Industrial production

Industrial production is a measure of output of the industrial sector of the economy. The industrial sector includes manufacturing, mining, and utilities. Although these sectors contribute only a small portion of gross domestic product (GDP), the ...

and trade was, partly due to geopolitical reality and economic necessity, redirected toward Germany. An overriding concern was a German fear of creating a burden if the Danish economy collapsed as it did after World War I. This sensitivity to Denmark's heavy reliance on foreign trade informed the German decision before the occupation to allow the Danes passage through their blockade. Denmark had traditionally been a major trading partner of both Britain and Germany. Many government officials saw expanded trade with Germany as vital to maintaining social order in Denmark. Increased unemployment and poverty were feared to lead to more of open revolt within the country, since Danes tended to blame all negative developments on the Germans. It was feared that any revolt would result in a crackdown by the German authorities.

* The Danish army was largely demobilized, although some units remained until August 1943. The army was allowed to maintain 2,200 men, as well as 1,100 auxiliary troops. Much of the fleet remained in port, but in Danish hands. In at least two towns, the army created secret weapons caches on 10 April 1940. On 23 April 1940,H.M. Lunding (1970), ', 3rd edition, Gyldendal, pages 68–72. members of the Danish military intelligence established contacts with their British counterparts through the British diplomatic mission in Stockholm, and began dispatching intelligence reports to them by Autumn 1940. This traffic became regular and continued until the Germans dissolved the Danish army in 1943. Following the liberation of Denmark, Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

Bernard Law Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and th ...

described the intelligence gathered in Denmark as "second to none".

In return for these concessions, the Danish cabinet rejected German demands for legislation discriminating against Denmark's Jewish minority. Demands to introduce the death penalty were likewise rebuffed, and so were German demands to allow German military courts jurisdiction over Danish citizens. Denmark also rejected demands for the transfer of Danish army units to German military use.

Stauning remained

Stauning remained prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

until his death in 1942, as head of a coalition cabinet

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

encompassing all major political parties (the exceptions being the tiny Nazi party, and the Communist Party which was outlawed in 1941). Vilhelm Buhl

Vilhelm Buhl (16 October 1881 – 18 December 1954) was Prime Minister of Denmark from 4 May 1942 to 9 November 1942 as head of the ''Unity Government'' (the Cabinet of Vilhelm Buhl I) during the German occupation of Denmark of World War II, unti ...

replaced him briefly, only to be replaced by foreign minister Erik Scavenius

Erik Julius Christian Scavenius (; 13 July 1877 – 29 November 1962) was the Danish foreign minister from 1909 to 1910, 1913 to 1920 and 1940 to 1943, and prime minister from 1942 to 1943, during the occupation of Denmark until the Danish electe ...

, who had been the main link to the Nazi authorities throughout the war. Scavenius was a diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

, not an elected politician, and had an elitist

Elitism is the belief or notion that individuals who form an elite—a select group of people perceived as having an intrinsic quality, high intellect, wealth, power, notability, special skills, or experience—are more likely to be construc ...

approach to government. He was afraid that emotional public opinion would destabilize his attempts to build a compromise between Danish sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

and the realities of German occupation. Scavenius felt strongly that he was Denmark's most ardent defender. After the war there was much recrimination over his stance, particularly from members of the active resistance, who felt that he had hindered the cause of resistance and threatened Denmark's national honour. He felt that these people were vain, seeking to build their own reputations or political careers through emotionalism.

The Danish authorities were able to use their more cooperative stance to win important concessions for the country. They continually refused to enter a

The Danish authorities were able to use their more cooperative stance to win important concessions for the country. They continually refused to enter a customs

Customs is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out of a country. Traditionally, customs ...

and currency union

A currency union (also known as monetary union) is an intergovernmental agreement that involves two or more State (polity), states sharing the same currency. These states may not necessarily have any Economic integration#Stages, further integratio ...

with Germany. Danes were concerned both about the negative economic effects of the German proposals, as well as the political ones. German officials did not want to risk their special relationship with Denmark by forcing an agreement on them, as they had done in other countries. The Danish government was also able to stall negotiations over the return of South Jutland to Germany, ban "closed-rank uniformed marches" that would have made nationalist German or Danish Nazi agitation more possible, keep National Socialists

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

out of the government, and hold a relatively free election, with decidedly anti-Nazi results, in the middle of the war. Danish military officials also had access to sensitive German information, which they delivered to the Allies under government cover. The economic consequences of the occupation were also mitigated by German-Danish cooperation. Inflation rose sharply in the first year of the war, as the German Army spent a large amount of German military currency in Denmark, most importantly on military installations and troop deployments. Due to the Occupation, the National Bank of Denmark was compelled to exchange German currency for Danish notes, effectively granting the Germans a gigantic unsecured loan with only vague promises that the money would eventually be paid, something which never happened. The Danish government was later able to renegotiate the Germans' arbitrary exchange rate between the German military currency and the Danish krone to reduce this problem.

The success most often alluded to in regard to the Danish policy toward Germany is the protection of the Jewish minority in Denmark. Throughout the years of its hold on power, the government consistently refused to accept German demands regarding the Jews. The authorities would not enact special laws concerning Jews, and their civil rights remained equal with those of the rest of the population. German authorities became increasingly exasperated with this position but concluded that any attempt to remove or mistreat Jews would be "politically unacceptable." Even the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

officer Dr. Werner Best

Karl Rudolf Werner Best (10 July 1903 – 23 June 1989) was a German jurist, police chief, SS-''Obergruppenführer'', Nazi Party leader, and theoretician from Darmstadt. He was the first chief of Department 1 of the Gestapo, Nazi Germany's secret ...

, plenipotentiary in Denmark from November 1942, believed that any attempt to remove the Jews would be enormously disruptive to the relationship between the two governments and recommended against any action concerning the Jews of Denmark.

King Christian X

Christian X ( da, Christian Carl Frederik Albert Alexander Vilhelm; 26 September 1870 – 20 April 1947) was List of Danish monarchs, King of Denmark from 1912 to his death in 1947, and the only List of rulers of Iceland, King of Iceland as ...

remained in Denmark throughout the war, a symbol of courage much appreciated by his subjects.

Collaborators

Free Corps Denmark

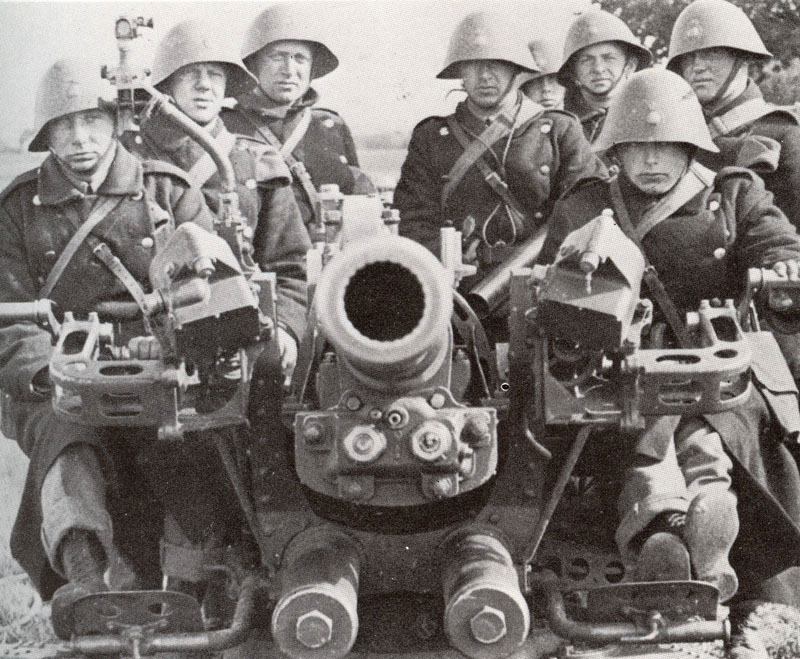

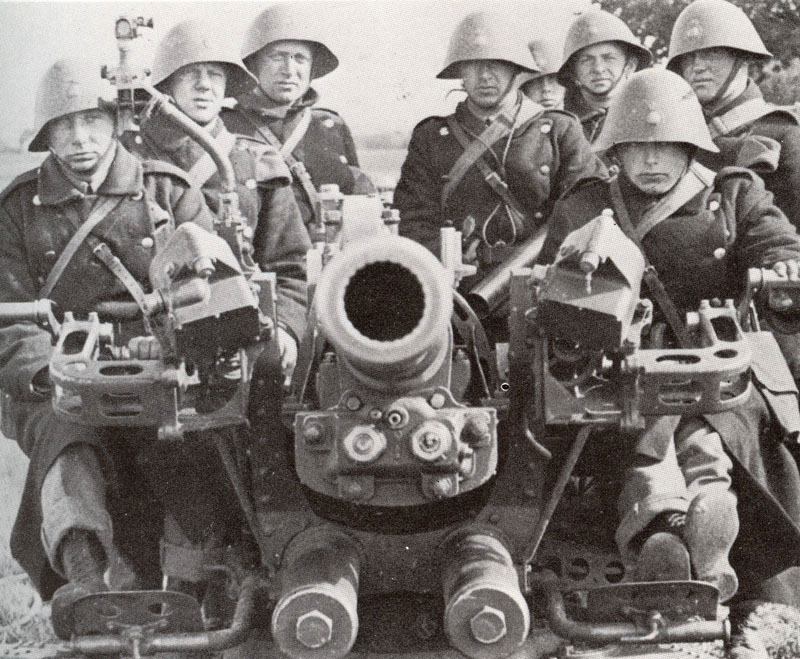

On 29 June 1941, days after the invasion of the USSR, ''Free Corps Denmark

Free Corps Denmark ( da, Frikorps Danmark) was a unit of the Waffen-SS during World War II consisting of collaborationist volunteers from Denmark. It was established following an initiative by the National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark (DNS ...

'' ( da, Frikorps Danmark) was founded as a corps of Danish volunteers to fight against the Soviet Union. ''Free Corps Denmark'' was set up at the initiative of the SS and DNSAP who approached Lieutenant-Colonel C.P. Kryssing of the Danish army shortly after the invasion of the USSR had begun. The Nazi paper ' proclaimed the creation of the corps on 29 June 1941.Bo Lidegaard (ed.) (2003): ''Dansk Udenrigspolitiks historie'', vol. 4, pp. 461–463

According to Danish law, it was not illegal to join a foreign army, but active recruiting on Danish soil was illegal. The SS disregarded this law and began recruiting efforts – predominantly recruiting Danish Nazis and members of the German-speaking minority. The Danish government discovered this and decided to concentrate on persuading the Germans not to recruit underage boys. General Prior wanted to remove Kryssing and his designated second-in-command but decided to consult the cabinet. It agreed that Kryssing should be removed in its meeting on 2 July 1941, but this decision was later withdrawn when Erik Scavenius—who had not attended the original meeting—returned from negotiations and announced that he had reached an agreement with Renthe-Fink that soldiers wishing to join this corps could be given leave until further notice. The government issued an announcement stating that "Lieut. Colonel C.P. Kryssing, Chief of the 5th Artillery reg., Holbæk, has with the consent of the Royal Danish Government assumed command over 'Free Corps Denmark'". The Danish text only explicitly said that the government recognized that Kryssing had been given a new command; it did not sanction the creation of the corps, which had already happened without its creators asking the government's consent. In July 1941

According to Danish law, it was not illegal to join a foreign army, but active recruiting on Danish soil was illegal. The SS disregarded this law and began recruiting efforts – predominantly recruiting Danish Nazis and members of the German-speaking minority. The Danish government discovered this and decided to concentrate on persuading the Germans not to recruit underage boys. General Prior wanted to remove Kryssing and his designated second-in-command but decided to consult the cabinet. It agreed that Kryssing should be removed in its meeting on 2 July 1941, but this decision was later withdrawn when Erik Scavenius—who had not attended the original meeting—returned from negotiations and announced that he had reached an agreement with Renthe-Fink that soldiers wishing to join this corps could be given leave until further notice. The government issued an announcement stating that "Lieut. Colonel C.P. Kryssing, Chief of the 5th Artillery reg., Holbæk, has with the consent of the Royal Danish Government assumed command over 'Free Corps Denmark'". The Danish text only explicitly said that the government recognized that Kryssing had been given a new command; it did not sanction the creation of the corps, which had already happened without its creators asking the government's consent. In July 1941 Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

complained that Denmark was unofficially trying to stop recruitment since the word ran in the army that anyone joining would be committing treason. The government later instructed the army and navy not to obstruct applications from soldiers wishing to leave active duty and join the corps.

A 1998 study showed that the average recruit to ''Free Corps Denmark'' was a Nazi, a member of the German minority in Denmark, or both, and that recruitment was very broad socially. Historian Bo Lidegaard notes: "The relationship between the population and the corps was freezing cold, and legionnaires on leave time and again came into fights, with civilians meeting the corps' volunteers with massive contempt." Lidegaard gives the following figures for 1941: 6,000 Danish citizens had signed up to German army duty; 1,500 of these belonged to the German minority in Denmark.

Anti-Comintern Pact

On 20 November 1941, 5 months after the invasion of the USSR, the Danish government received a German "invitation" to join theAnti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

. Finland accepted reluctantly on 25 November and stated that it presumed that Denmark would also attend the ceremony (effectively conditioning its own attendance). Erik Scavenius argued that Denmark should sign the pact but the Cabinet ministers refused, stating that this would violate the policy of neutrality.Bo Lidegaard (ed.) (2003): ''Dansk Udenrigspolitiks historie'', vol. 4, pp. 474–483 Scavenius reported this decision to Renthe-Fink. Fink replied on 21 November that "Germany would be unable to comprehend" a Danish rejection and demanded this decision be reversed before the end of the day. He assured Scavenius that the pact contained neither "political or other obligations" (i.e., going to war with the USSR). At a cabinet meeting the same day, it was suggested to seek written confirmation of this promise in an addendum to the protocol. Stauning agreed on these terms since it would effectively make the signing meaningless. The Danish foreign office drew up a list of four terms that stated that Denmark only committed itself to "police action" in Denmark and that the nation remained neutral. The German foreign ministry agreed to the terms, provided that the protocol was not made public, which was the intent of the Danish foreign ministry.

As Berlin grew tired of waiting, Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

called Copenhagen on 23 November threatening to "cancel the peaceful occupation" unless Denmark complied. On 23 November, the ' in Denmark was put on alert and Renthe-Fink met Stauning and Foreign Minister Munch at 10 AM stating that there would be no room for "parliamentary excuses". If the German demands were not met Germany "would no longer be committed by the promises given on 9 April 1940" (the threat of a state of war, a Nazi government, and territorial dismemberment). In a Cabinet meeting at 2 PM that day, Stauning, Scavenius, Munch and two additional ministers advocated accession; seven ministers opposed. In a meeting the same day in the Nine Man committee, three more ministers caved in, most notably Vilhelm Buhl, stating "Cooperation is the last shred of our defence". Prime Minister Stauning's notes from the day stated: ''The objective is a political positioning. But this was established by the occupation. The danger of saying no—I would not like to see a Terboven here. Sign with addendum—that modifies the pact.''

Scavenius boarded a train and headed for Berlin, where he arrived on Monday 24 November. The next crisis came when he was met by Renthe-Fink, who informed him that Ribbentrop had informed Fink that there had been a "misunderstanding" regarding the four clauses and that clause 2 would be deleted. This had specified that Denmark only had police-like obligations. Scavenius had a strict mandate not to change a sentence and stated that he would be unable to return to Copenhagen with a different content from the one agreed upon, but that he was willing to reopen negotiations to clarify the matter further. This reply enraged Ribbentrop (and rumours claim that he was considering ordering the SS to arrest Scavenius). The task fell to German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker

Ernst Heinrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker (25 May 1882 – 4 August 1951) was a German naval officer, diplomat and politician. He served as State Secretary at the Foreign Office of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1943, and as its Ambassador to ...

to patch up a compromise. He watered down the wording but left the content pretty intact. Nonetheless, for Scavenius it was a strong setback that the four clauses would now only get the status of a unilateral Danish declaration (') with a comment on it by Fink that its content "no doubt" was in compliance with the pact. Furthermore, he was instructed to give a public speech while abstaining from mentioning the four clauses but only making general statements about Denmark's status as a neutral nation. Scavenius signed the pact. At the following reception, the Italian ambassador described Scavenius as "a fish dragged on land ... a small old gentleman in a suit asking himself how on earth he got to this place". Lidegaard comments that the old man remained defiant: during a conversation with Ribbentrop in which the latter complained about the "barbarous cannibalism" of Russian POWs, Scavenius rhetorically asked if that statement meant that Germany didn't feed her prisoners.

When news of the signing reached Denmark, it left the population outraged, and rumours immediately spread about what Denmark had now committed itself to. The cabinet sent a car to pick up Scavenius at the ferry, to avoid his riding the train alone to Copenhagen. At the same time a large demonstration gathered outside of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, which led the Minister of Justice, Eigil Thune Jacobsen, to remark that he did not like to see Danish police beating up students singing patriotic songs. When Scavenius had returned to Copenhagen, he asked the cabinet to debate once and for all where the red lines existed in Danish relations with Germany. This debate concluded that three red lines existed:

# No legislation discriminating against Jews,

# Denmark should never join the Axis Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive military ...

between Germany, Italy, and Japan,

# No unit of the Danish army should ever fight against foreign forces.

To the surprise of many, Scavenius accepted these instructions without hesitation.

The 1942 telegram crisis

In October 1942,Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

transmitted a long, flattering birthday telegram to King Christian. The King replied with a simple ' ("Giving my best thanks. King Christian") sending the Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the Umlaut (diacritic), umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or "guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi Germany, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany ...

into a state of rage at this deliberate slight, and seriously damaging Danish relations with Germany. Hitler immediately recalled his ambassador and expelled the Danish ambassador from Germany. The plenipotentiary, Renthe-Fink was replaced by Werner Best and orders to crack down in Denmark were issued. Hitler also demanded that Erik Scavenius become prime minister, and all remaining Danish troops were ordered out of Jutland.

Increasing resistance after the August 1943 crisis

As the war dragged on, the Danish population became increasingly hostile to the Germans. Soldiers stationed in Denmark had found most of the population cold and distant from the beginning of the occupation, but their willingness to cooperate had made the relationship workable. The government had attempted to discourage sabotage and violent resistance to the occupation, but by the autumn of 1942 the numbers of violent acts of resistance were increasing steadily to the point that Germany declared Denmark "enemy territory" for the first time. After the battles ofStalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stal ...

and El-Alamein

El Alamein ( ar, العلمين, translit=al-ʿAlamayn, lit=the two flags, ) is a town in the northern Matrouh Governorate of Egypt. Located on the Arab's Gulf, Mediterranean Sea, it lies west of Alexandria and northwest of Cairo. , it had ...

the incidents of resistance, violent and symbolic, increased rapidly.

In March 1943 the Germans allowed a general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

to be held. The voter turnout was 89.5%, the highest in any Danish parliamentary election, and 94% cast their ballots for one of the democratic parties behind the cooperation policy while 2.2% voted for the anti-cooperation '. 2.1% voted for the National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark

The National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark ( da, Danmarks Nationalsocialistiske Arbejderparti; DNSAP) was the largest Nazi Party in Denmark before and during the Second World War.

History

The party was founded on 16 November 1930, after ...

, almost corresponding to the 1.8% the party had received in the 1939 elections. The election, discontent, and a growing feeling of optimism that Germany would be defeated led to widespread strikes and civil disturbance

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty ...

s in the summer of 1943. The Danish government refused to deal with the situation in a way that would satisfy the Germans, who presented an ultimatum to the government, including the following demands, on 28 August 1943: A ban on people assembling in public, outlawing strikes, the introduction of a curfew, censorship should be conducted with German assistance, special (German military) courts should be introduced, and the death penalty should be introduced in cases of sabotage. In addition, the city of Odense

Odense ( , , ) is the third largest city in Denmark (behind Copenhagen and Aarhus) and the largest city on the island of Funen. As of 1 January 2022, the city proper had a population of 180,863 while Odense Municipality had a population of 20 ...

was ordered to pay a fine of 1 million kroner for the death of a German soldier killed in that city and hostages were to be held as security.

The Danish government refused, so on 29 August 1943 the Germans officially dissolved the Danish government and instituted

The Danish government refused, so on 29 August 1943 the Germans officially dissolved the Danish government and instituted martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. The Danish cabinet handed in its resignation, although since King Christian never officially accepted it, the government remained functioning ' until the end of the war. In reality—largely due to the initiative of the permanent secretary of the ministry of foreign affairs Nils Svenningsen

Nils is a Scandinavian given name, a chiefly Norwegian, Danish, Swedish and Latvian variant of Niels, cognate to Nicholas.

People and animals with the given name

* Nils Bergström (born 1985), Swedish ice hockey player

*Nils Björk (1898–1989), ...

—all day-to-day business had been handed over to the Permanent Secretaries, each effectively running his own ministry. The Germans administered the rest of the country, and the Danish Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

did not convene for the remainder of the occupation. As the ministry of foreign affairs was responsible for all negotiations with the Germans, Nils Svenningsen had a leading position in the government.

In anticipation of

In anticipation of Operation Safari

Operation Safari (german: Unternehmen Safari) was a German military operation during World War II aimed at disarming the Danish military. It led to the scuttling of the Royal Danish Navy and the internment of all Danish soldiers. Danish forces s ...

, the Danish Navy

The Royal Danish Navy ( da, Søværnet) is the sea-based branch of the Danish Defence force. The RDN is mainly responsible for maritime defence and maintaining the sovereignty of Danish territorial waters (incl. Faroe Islands and Greenland). Oth ...

had instructed its captains to resist any German attempts to assume control over their vessels. The navy managed to scuttle 32 of its larger ships, while Germany succeeded in seizing 14 of the larger and 50 of the smaller vessels (' or "patrol cutters"). The Germans later succeeded in raising and refitting 15 of the sunken ships. During the scuttling of the Danish fleet, a number of vessels were ordered to attempt an escape to Swedish waters, and 13 vessels succeeded in this attempt, four of which were the larger ships; two of the larger vessels had remained at safe harbour in Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

. The coastal defence ship

Coastal defence ships (sometimes called coastal battleships or coast defence ships) were warships built for the purpose of coastal defence, mostly during the period from 1860 to 1920. They were small, often cruiser-sized warships that sacrifi ...

attempted to break out of the Isefjord

Ise Fjord ( da, Isefjorden) is a deeply branched arm of the sea into the Danish island Zealand.

From its relatively narrow entrance from the Kattegat at Hundested and Rørvig, branches of Ise Fjord stretch 35 km inland and divide the norther ...

, but was attacked by Stukas and forced to run aground. By the autumn of 1944, the ships in Sweden officially formed a Danish naval flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' (fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same class ...

in exile. In 1943, Swedish authorities allowed 500 Danish soldiers in Sweden to train themselves as "police troops". By the autumn of 1944, Sweden raised this number to 4,800 and recognized the entire unit as a Danish brigade in exile. Danish collaboration continued on an administrative level, with the Danish bureaucracy functioning under German command.

In September 1943, a variety of resistance groups grouped together in the Danish Freedom Council, which coordinated resistance activities. A high-profile resister was former government minister

In September 1943, a variety of resistance groups grouped together in the Danish Freedom Council, which coordinated resistance activities. A high-profile resister was former government minister John Christmas Møller

Guido Leo John Christmas Møller, usually known as Christmas Møller (3 April 1894 in Copenhagen – 13 April 1948 in Copenhagen) was a Danish politician representing the Conservative People's Party.

Life

Møller was elected as a Conserva ...

, who had fled to England in 1942 and became a widely popular commentator because of his broadcasts to the nation over the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

increased greatly in frequency and severity, though it was rarely of very serious concern to the Germans. Nonetheless, the Danish resistance movement

The Danish resistance movements ( da, Den danske modstandsbevægelse) were an underground insurgency to resist the German occupation of Denmark during World War II. Due to the initially lenient arrangements, in which the Nazi occupation autho ...

had some successes, such as on D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as D ...

when the train network in Denmark was disrupted for days, delaying the arrival of German reinforcements in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

. An underground government was established, and the illegal press flourished. Allied governments, which had been sceptical about the country's commitment to fight Germany, began recognizing Denmark as a full ally.

The permanent secretary of the ministry of foreign affairs, Nils Svenningsen, in January 1944 suggested establishment of a Danish camp, in order to avoid deportations to Germany. Werner Best accepted this suggestion, but on condition that this camp was built close to the German border. Frøslev Prison Camp

Frøslev Camp ( da, Frøslevlejren, german: Polizeigefangenenlager Fröslee) was an internment camp in German-occupied Denmark during World War II.

In order to avoid deportation of Danes to German concentration camps, Danish authorities suggest ...

was set up in August 1944. The building of the camp was for the sole purpose of keeping Danish Jews and other prisoners within Denmark's borders.

The Gestapo had limited trust in the Danish police, which had a total 10,000 members; 1,960 of these were arrested and deported to Germany on 19 September 1944.

Economy

Denmark faced some serious economic problems during the war. The Danish economy was fundamentally hurt by the rising cost of raw material imports such as coal andoil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

. Furthermore, Denmark lost its main trading partner at that point, the UK. During years of occupation the Danish economy was more and more aligned on meeting German demands, which mainly meant agrarian products. The Danish authorities took an active part in the development and even initiated negotiations on a customs union. Those negotiations failed on the question whether the Danish krone should be abolished.

The blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

against Germany affected Denmark too with unfortunate results. Since the country has virtually no natural resources

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. O ...

of its own it was very vulnerable to these price shocks and shortages. The government had foreseen the possibility of coal and oil shortages and had stockpiled some before the war, which, combined with rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

, prevented some of the worst potential problems from coming to the country. The disruptions to the European trading network were also damaging to the economy, but all things considered, Denmark did quite well compared to other countries during the war.

The country, at least certain sections of it, did so well that it has been open to the accusation of profiteering from the war. After the war there was some effort to find and punish profiteers, but the consequences and scope of these trials were far less severe than in many other countries, largely a reflection of the general acceptance of the realistic need for cooperation with Germany. On the whole, though the country fared relatively well, this is only a relative measure. Phil Giltner has worked out that Germany had a "debt" of roughly 6.9 billion kroner to Denmark as a whole. This means that they had taken far more out of the Danish economy than they had put in, aside from the negative side effects of the war on trade. The German debt had accumulated due to an arrangement with the Danish central bank, in which the German occupation forces could draw on a special account there to pay their bills from Danish suppliers. Exports to Germany were also largely settled this way. The arrangement was agreed to for fear of German soldiers helping themselves without paying, and the conflicts that might follow. It also meant that the Danish central bank was picking up a large part of the tab for the German occupation, and that the money supply rose drastically as a result.

Post-war currency reform

The Danish National Bank estimates that the occupation had resulted in the printing press increasing the currency supply from the pre-war figure of 400 million kroner to 1,600 million, much of which ended up in the hands ofwar profiteer

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteering, making a profit criticized a ...

s. In July 1945, two months after the liberation of Denmark, the Danish Parliament