Germaine de Staël on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (; ; 22 April 176614 July 1817), commonly known as Madame de Staël (), was a French woman of letters and

Lord Byron and Germaine de Staël

The University of Nottingham Her intellectual collaboration with

Germaine (or ''Minette'') was the only child of the Swiss

Germaine (or ''Minette'') was the only child of the Swiss

/ref> The family eventually took up residence in 1784 at Château Coppet, an estate on

Aged 11, Germaine had suggested to her mother that she marry

Aged 11, Germaine had suggested to her mother that she marry

In 1788, de Staël published ''Letters on the works and character of J.J. Rousseau''. In this

In 1788, de Staël published ''Letters on the works and character of J.J. Rousseau''. In this  Following the

Following the

After her flight from Paris, de Staël moved to

After her flight from Paris, de Staël moved to

In the summer of 1793, de Staël returned to Switzerland, probably because De Narbonne had cooled towards her. She published a defence of the character of

In the summer of 1793, de Staël returned to Switzerland, probably because De Narbonne had cooled towards her. She published a defence of the character of

/ref> In his opinion a woman should stick to knitting. He said about her, according to the Memoirs of Madame de Rémusat, that she "teaches people to think who had never thought before, or who had forgotten how to think". It became clear that the first man of France and de Staël were not likely ever to get along together. De Staël published a provocative, anti-Catholic novel '' Delphine'', in which the ''femme incomprise'' (misunderstood woman) living in Paris between 1789 and 1792, is confronted with conservative ideas about divorce after the

With her children and Constant, de Staël stopped off in

With her children and Constant, de Staël stopped off in

The operations of the French imperial police in the case of de Staël are rather obscure. She was at first left undisturbed, but by degrees, the chateau itself became a source of suspicion, and her visitors found themselves heavily persecuted. François-Emmanuel Guignard, De Montmorency and Mme Récamier were exiled for the crime of visiting her. She remained at home during the winter of 1811, planning to escape to England or Sweden with the manuscript. On 23 May 1812, she left Coppet under the pretext of a short outing, but journeyed through

The operations of the French imperial police in the case of de Staël are rather obscure. She was at first left undisturbed, but by degrees, the chateau itself became a source of suspicion, and her visitors found themselves heavily persecuted. François-Emmanuel Guignard, De Montmorency and Mme Récamier were exiled for the crime of visiting her. She remained at home during the winter of 1811, planning to escape to England or Sweden with the manuscript. On 23 May 1812, she left Coppet under the pretext of a short outing, but journeyed through  After four months of travel, de Staël arrived in Sweden. In Stockholm, she began writing her "Ten Years' Exile", detailing her travels and encounters. She did not finish the manuscript and after eight months, she set out for England, without August Schlegel, who meanwhile had been appointed secretary to the Crown Prince Carl Johan, formerly French Marshal

After four months of travel, de Staël arrived in Sweden. In Stockholm, she began writing her "Ten Years' Exile", detailing her travels and encounters. She did not finish the manuscript and after eight months, she set out for England, without August Schlegel, who meanwhile had been appointed secretary to the Crown Prince Carl Johan, formerly French Marshal

When news came of Napoleon's landing on the Côte d'Azur, between

When news came of Napoleon's landing on the Côte d'Azur, between

Besides two daughters, Gustava Sofia Magdalena (born July 1787) and Gustava Hedvig (born August 1789), both died in infancy, de Staël had two sons, Ludwig August (1790–1827), Albert (1792–1813), and a daughter, Albertine, baroness Staël von Holstein (1797–1838). It is believed Louis, Comte de Narbonne-Lara was the father of Ludvig August and Albert, and Benjamin Constant the father of red-haired Albertine. With Albert de Rocca, de Staël then aged 46, had one son, the disabled Louis-Alphonse de Rocca (1812–1842), who married Marie-Louise-Antoinette de Rambuteau, daughter of

Besides two daughters, Gustava Sofia Magdalena (born July 1787) and Gustava Hedvig (born August 1789), both died in infancy, de Staël had two sons, Ludwig August (1790–1827), Albert (1792–1813), and a daughter, Albertine, baroness Staël von Holstein (1797–1838). It is believed Louis, Comte de Narbonne-Lara was the father of Ludvig August and Albert, and Benjamin Constant the father of red-haired Albertine. With Albert de Rocca, de Staël then aged 46, had one son, the disabled Louis-Alphonse de Rocca (1812–1842), who married Marie-Louise-Antoinette de Rambuteau, daughter of

* ''Journal de Jeunesse'', 1785

* ''Sophie ou les sentiments secrets'', 1786 (published anonymously in 1790)

* ''Jane Gray'', 1787 (published in 1790)

* ''Lettres sur le caractère et les écrits de J.-J. Rousseau'', 1788

* ''Éloge de M. de Guibert''

* ''À quels signes peut-on reconnaître quelle est l'opinion de la majorité de la nation?''

* ''Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine'', 1793

* ''Zulma : fragment d'un ouvrage'', 1794

* ''Réflexions sur la paix adressées à M. Pitt et aux Français'', 1795

* ''Réflexions sur la paix intérieure''

* ''Recueil de morceaux détachés (comprenant : Épître au malheur ou Adèle et Édouard, Essai sur les fictions et trois nouvelles : Mirza ou lettre d'un voyageur, Adélaïde et Théodore et Histoire de Pauline)'', 1795

* ''Essai sur les fictions'', translated by Goethe into German

* ''De l'influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations'', 1796

* ''Des circonstances actuelles qui peuvent terminer la Révolution et des principes qui doivent fonder la République en France''

* ''De la littérature dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales'', 1799

* '' Delphine'', 1802 deals with the question of woman's status in a society hidebound by convention and faced with a Revolutionary new order

* ''Vie privée de Mr. Necker'', 1804

* ''Épîtres sur Naples''

* '' Corinne, ou l'Italie'', 1807 is as much a travelogue as a fictional narrative. It discusses the problems of female artistic creativity in two radically different cultures, England and Italy.

* ''Agar dans le désert''

* ''Geneviève de Brabant''

* ''La Sunamite''

* ''Le capitaine Kernadec ou sept années en un jour (comédie en deux actes et en prose)''

* ''La signora Fantastici''

* ''Le mannequin (comédie)''

* ''Sapho''

* ''

* ''Journal de Jeunesse'', 1785

* ''Sophie ou les sentiments secrets'', 1786 (published anonymously in 1790)

* ''Jane Gray'', 1787 (published in 1790)

* ''Lettres sur le caractère et les écrits de J.-J. Rousseau'', 1788

* ''Éloge de M. de Guibert''

* ''À quels signes peut-on reconnaître quelle est l'opinion de la majorité de la nation?''

* ''Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine'', 1793

* ''Zulma : fragment d'un ouvrage'', 1794

* ''Réflexions sur la paix adressées à M. Pitt et aux Français'', 1795

* ''Réflexions sur la paix intérieure''

* ''Recueil de morceaux détachés (comprenant : Épître au malheur ou Adèle et Édouard, Essai sur les fictions et trois nouvelles : Mirza ou lettre d'un voyageur, Adélaïde et Théodore et Histoire de Pauline)'', 1795

* ''Essai sur les fictions'', translated by Goethe into German

* ''De l'influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations'', 1796

* ''Des circonstances actuelles qui peuvent terminer la Révolution et des principes qui doivent fonder la République en France''

* ''De la littérature dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales'', 1799

* '' Delphine'', 1802 deals with the question of woman's status in a society hidebound by convention and faced with a Revolutionary new order

* ''Vie privée de Mr. Necker'', 1804

* ''Épîtres sur Naples''

* '' Corinne, ou l'Italie'', 1807 is as much a travelogue as a fictional narrative. It discusses the problems of female artistic creativity in two radically different cultures, England and Italy.

* ''Agar dans le désert''

* ''Geneviève de Brabant''

* ''La Sunamite''

* ''Le capitaine Kernadec ou sept années en un jour (comédie en deux actes et en prose)''

* ''La signora Fantastici''

* ''Le mannequin (comédie)''

* ''Sapho''

* ''Ten Years' Exile by Madame de Staël

/ref> * ''Essais dramatiques'', 1821 * ''Oeuvres complètes'' 17 t., 1820–21 *

Volume 1Volume 2

''Madame de Staël''

New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005 (hardcover, ); 2006 (paperback, ); London: Constable & Robinson, 2005 (hardcover, ); 2006 (paperback, ). * * Hilt, Douglas. "Madame De Staël: Emotion and Emancipation". ''History Today'' (Dec 1972), Vol. 22 Issue 12, pp. 833–842, online. * * * * Winegarten, Renee. ''Germaine de Staël & Benjamin Constant: A Dual Biography''. New Haven:

Stael and the French Revolution Introduction by Aurelian Craiutu

BBC4 In Our Time on Germaine de Staël

Madame de Staël and the Transformation of European Politics, 1812–17 by Glenda Sluga. In: The International history review 37(1):142–166 · November 2014

*

Stael.org

wit

detailed chronology

*

BNF.fr

(Searching "stael"). * * *

in ''The Columbia Encyclopedia'', Sixth Edition: 2001–05.

The Great de Staël

by Richard Holmes from ''

political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be Academia, academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized b ...

, the daughter of banker and French finance minister Jacques Necker and Suzanne Curchod Suzanne Curchod (1737 – 6 May 1794) was a French-Swiss salonist and writer. She hosted one of the most celebrated salons of the Ancien Régime. She also led the development of the Hospice de Charité, a model small hospital in Paris that still ...

, a leading salonnière

A salon is a gathering of people held by an inspiring host. During the gathering they amuse one another and increase their knowledge through conversation. These gatherings often consciously followed Horace's definition of the aims of poetry, "ei ...

. She was a voice of moderation in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislativ ...

up to the French Restoration

The Bourbon Restoration was the period of French history during which the House of Bourbon returned to power after the first fall of Napoleon on 3 May 1814. Briefly interrupted by the Hundred Days War in 1815, the Restoration lasted until the J ...

. She was present at the Estates General of 1789

The Estates General of 1789 was a general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate). It was the last of the Estates General of the Kingdom o ...

and at the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

.Bordoni, Silvia (2005Lord Byron and Germaine de Staël

The University of Nottingham Her intellectual collaboration with

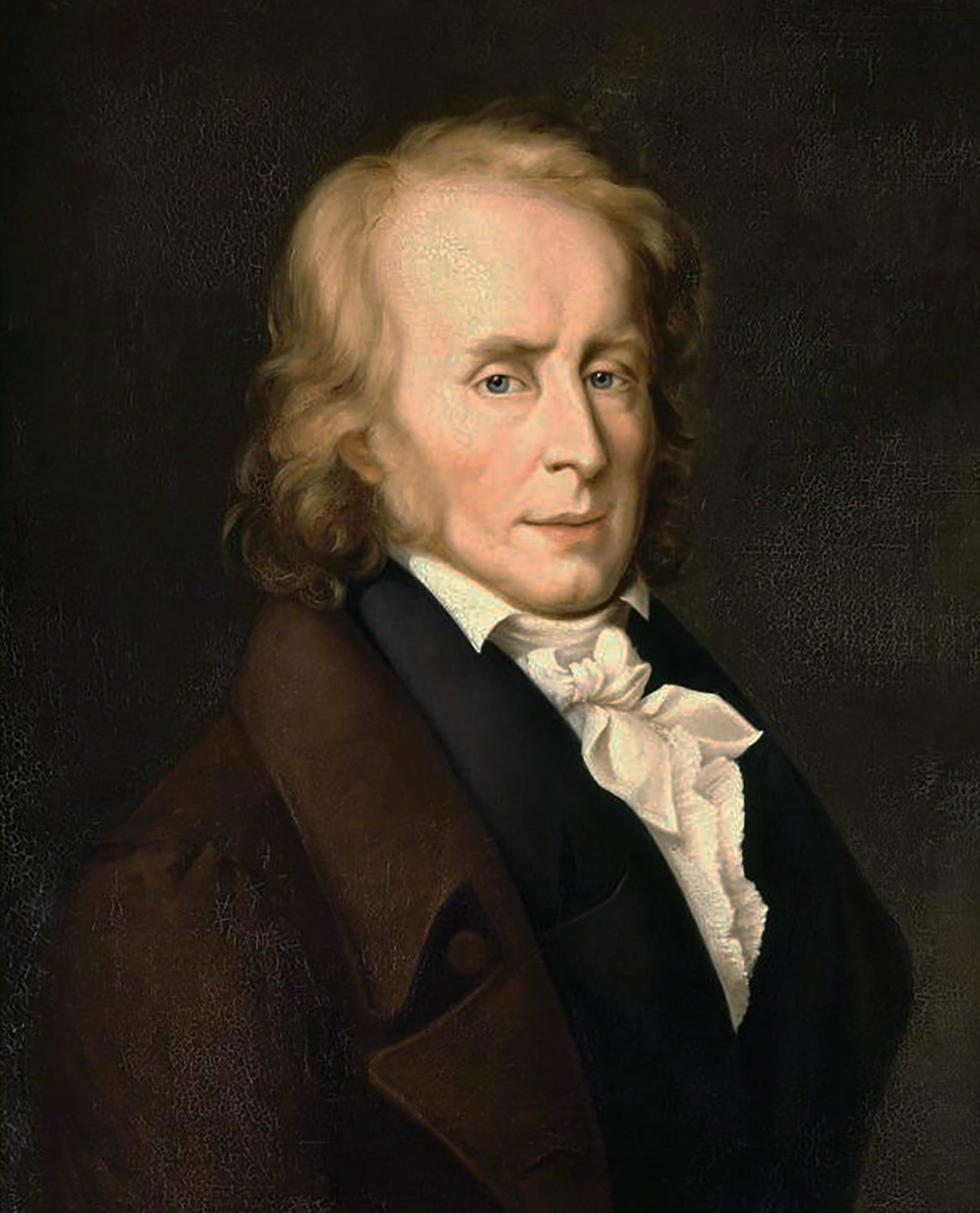

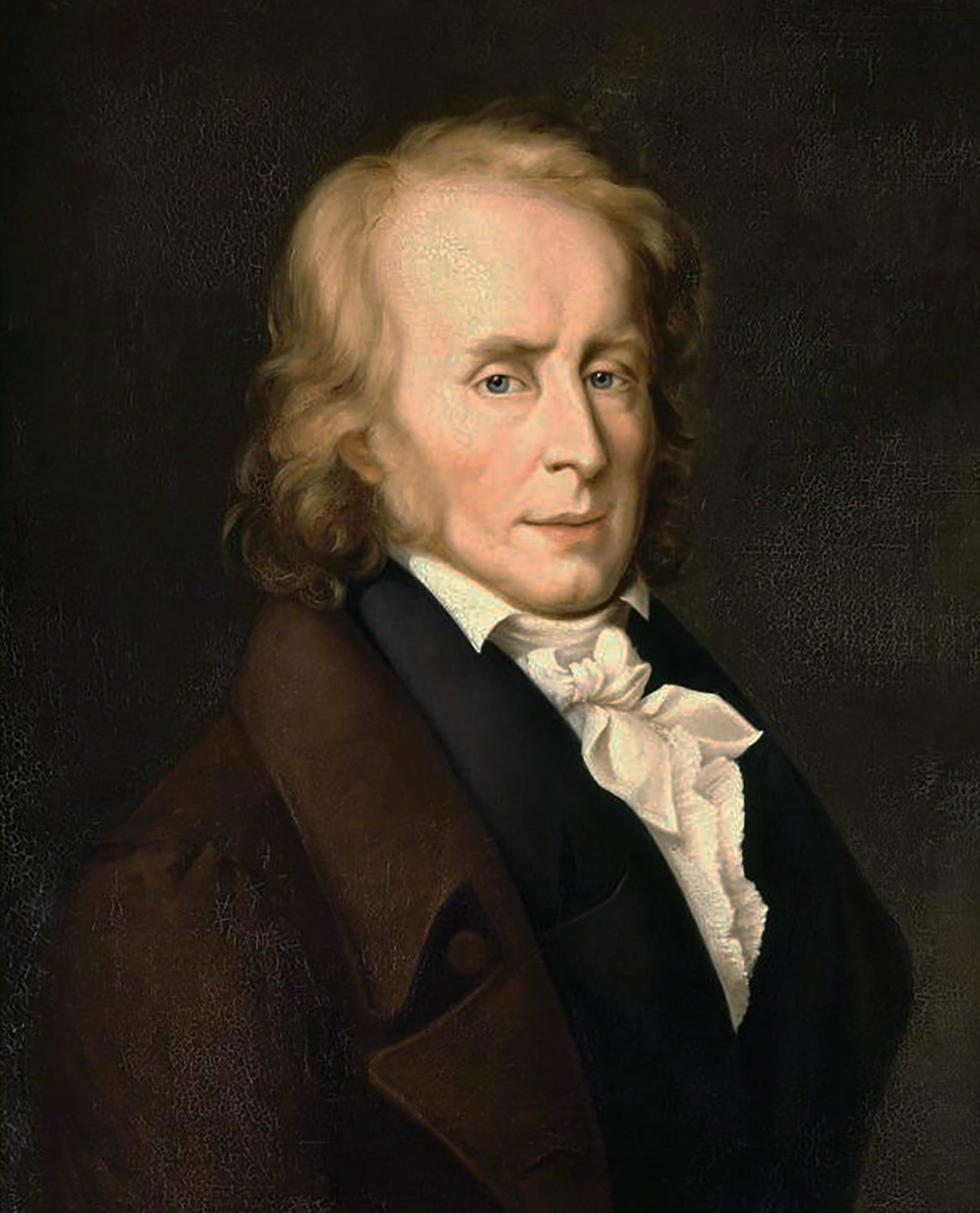

Benjamin Constant

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (; 25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), or simply Benjamin Constant, was a Franco-Swiss political thinker, activist and writer on political theory and religion.

A committed republican from 1795, he backed t ...

between 1794 and 1810 made them one of the most celebrated intellectual couples of their time. She discovered sooner than others the tyrannical character and designs of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

. For many years she lived as an exile – firstly during the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

and later due to personal persecution by Napoleon.

In exile, she became the centre of the Coppet group

The Coppet group (''Groupe de Coppet''), also known as the Coppet circle, was an informal intellectual and literary gathering centred on Germaine de Staël during the time period between the establishment of the Napoleonic First Empire (1804) a ...

with her unrivalled network of contacts across Europe. In 1814 one of her contemporaries observed that "there are three great powers struggling against Napoleon for the soul of Europe: England, Russia, and Madame de Staël". Known as a witty and brilliant conversationalist, and often dressed in daring outfits, she stimulated the political and intellectual life of her times. Her works, whether novels, travel literature

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern pe ...

or polemics, which emphasised individuality and passion, made a lasting mark on European thought. De Staël spread the notion of Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

widely by its repeated use.

Childhood

governess

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, ...

Suzanne Curchod Suzanne Curchod (1737 – 6 May 1794) was a French-Swiss salonist and writer. She hosted one of the most celebrated salons of the Ancien Régime. She also led the development of the Hospice de Charité, a model small hospital in Paris that still ...

with aptitude for mathematics and science and prominent Swiss banker and statesman Jacques Necker. He became the Director-General of Finance under King Louis XVI of France

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

and she hosted in Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin

This "quartier" of Paris got its name from the rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. It runs north-northwest from the Boulevard des Italiens to the Église de la Sainte-Trinité, Paris, Église de la Sainte-Trinité.

In ...

one of the most popular salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ( ...

s of Paris. Mme Necker wanted her daughter educated according to the principles of the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

and endow her with the intellectual education and Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

discipline instilled in her by her father. On Fridays she regularly brought Germaine as a young child to sit at her feet in her salon, where the guests took pleasure in stimulating the brilliant child. At the age of 13, she read Montesquieu, Shakespeare, Rousseau and Dante. Her parents' social life led to a somewhat neglected and wild Germaine, unwilling to bow to her mother's demands.

Her father "is remembered today for taking the unprecedented step in 1781 of making public the country’s budget, a novelty in an absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

where the state of the national finances had always been kept secret, leading to his dismissal in May of that year."Stael and the French Revolution Introduction by Aurelian Craiutu/ref> The family eventually took up residence in 1784 at Château Coppet, an estate on

Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

. The family returned to the Paris region in 1785.

Marriage

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, i ...

, a visitor to her salon, whom she found most attractive. Then, she reasoned, he would always be around for her. In 1783, at seventeen, she was courted by William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ir ...

and by Comte de Guibert, whose conversation, she thought, was the most far-ranging, spirited and fertile she had ever known. When she did not accept their offers Germaine's parents became impatient. With the help of Marie-Charlotte Hippolyte de Boufflers, a marriage was arranged with Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein

Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein, (25 October 1749, Loddby, Sweden – 9 May 1802, Poligny, France) was a Swedish diplomat, soldier and courtier best known for being Sweden's Ambassador to France during the end of the Ancien Regime and the ea ...

, a Protestant and attaché of the Swedish legation to France. The wedding took place on 14 January 1786 in the Swedish embassy at 97, Rue du Bac; Germaine was 20, her husband 37. On the whole, the marriage seems to have been workable for both parties, although neither seems to have had much affection for the other. Mlle Necker continued to write miscellaneous works, including the three-act romantic drama ''Sophie'' (1786) and the five-act tragedy, ''Jeanne Grey'' (1787). The baron, also a gambler, obtained great benefits from the match as he received 80,000 pounds and was confirmed as lifetime ambassador to Paris, although his wife would become almost certainly the more effective envoy.

Revolutionary activities

In 1788, de Staël published ''Letters on the works and character of J.J. Rousseau''. In this

In 1788, de Staël published ''Letters on the works and character of J.J. Rousseau''. In this panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of gr ...

, written initially for a limited number of friends (in which she considered his housekeeper Thérèse Levasseur

Marie-Thérèse Levasseur (; 21 September 1721 – 12 July 1801; also known as ''Thérèse Le Vasseur'', ''Lavasseur'') was the domestic partner, mistress, wife and widow of Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Biography

Thérèse Le Va ...

as unfaithful), she demonstrated evident talent, but little critical discernment. De Staël was at this time enthusiastic about the mixture of Rousseau's ideas about love and Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

's on politics.

In December 1788 her father persuaded the king to double the number of deputies at the Third Estate in order to gain enough support to raise taxes to defray the excessive costs of supporting the revolutionaries in America. This approach had serious repercussions on Necker's reputation; he appeared to consider the Estates-General as a facility designed to help the administration rather than to reform the government. In an argument with the king, whose speech on 23 June he didn't attend, Necker was dismissed and exiled on 11 July. Her parents left France on the same day in unpopularity and disgrace. On Sunday, 12 July the news became public, and an angry Camille Desmoulins

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins (; 2 March 17605 April 1794) was a French journalist and politician who played an important role in the French Revolution. Desmoulins was tried and executed alongside Georges Danton when the Committee ...

suggested storming the Bastille. On 16 July he was reappointed; Necker entered Versailles in triumph. His efforts to clean up public finances were unsuccessful and his idea of a National Bank failed. Necker was attacked by Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (; born Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the '' sans-culottes'', a radica ...

and Count Mirabeau

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New Yor ...

in the Constituante, when he did not agree with using assignat

An assignat () was a monetary instrument, an order to pay, used during the time of the French Revolution, and the French Revolutionary Wars.

France

Assignats were paper money (fiat currency) issued by the Constituent Assembly in France from 1 ...

s as legal tender

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in ...

. He resigned on 4 September 1790. Accompanied by their son-in-law, her parents left for Switzerland, without the two million livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 g ...

, half of his fortune, loaned as an investment in the public treasury in 1778.

The increasing disturbances caused by the Revolution made her privileges as the consort of an ambassador an important safeguard. Germaine held a salon in the Swedish embassy, where she gave "coalition dinners", which were frequented by moderates such as Talleyrand and De Narbonne, monarchists ( Feuillants) such as Antoine Barnave, Charles Lameth and his brothers Alexandre and Théodore, the Comte de Clermont-Tonnerre, Pierre Victor, baron Malouet, the poet Abbé Delille, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, the one-legged Minister Plenipotentiary

An envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, usually known as a minister, was a diplomatic head of mission who was ranked below ambassador. A diplomatic mission headed by an envoy was known as a legation rather than an embassy. Under the ...

to France Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to th ...

, Paul Barras (from the Plain) and the Girondin Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal p ...

s. "The issue of leadership, or rather lack of it, was central to de Staël's preoccupations at this stage of her political reflections. She experienced the death of Mirabeau, accused of royalism, as a sign of great political disorientation and uncertainty. He was the only man with the necessary charisma, energy, and prestige to keep the revolutionary movement on a path of constitutional reform

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, t ...

."

Following the

Following the 1791 French legislative election

French legislative elections were held in September 1791 to elect the Legislative Assembly and was the first ever French election. However, only citizens paying taxes were allowed to vote. A plurality of the elected candidates were independents, ...

, and after the French Constitution of 1791

The French Constitution of 1791 (french: Constitution française du 3 septembre 1791) was the first written constitution in France, created after the collapse of the absolute monarchy of the . One of the basic precepts of the French Revolution ...

was announced in the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

, she resigned from a political career and decided not to stand for re-election. "Fine arts and letters will occupy my leisure." She did, however, play an important role in the succession of Comte de Montmorin the Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

, and in the appointment of Narbonne as minister of War and continued to be centre stage behind the scenes. Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

wrote to Hans Axel Fersen

Hans Axel von Fersen (; 4 September 175520 June 1810), known as Axel de Fersen in France, was a Swedish count, Marshal of the Realm of Sweden, a General of Horse in the Royal Swedish Army, one of the Lords of the Realm, aide-de-camp to Rocham ...

: "Count Louis de Narbonne is finally Minister of War, since yesterday; what a glory for Mme de Staël and what a joy for her to have the whole army, all to herself."

In 1792 the French Legislative Assembly saw an unprecedented turnover of ministers, six ministers of the interior, seven ministers of foreign affairs, and nine ministers of war. On 10 August 1792 Clermont-Tonnere was thrown out of a window of the Louvre Palace

The Louvre Palace (french: link=no, Palais du Louvre, ), often referred to simply as the Louvre, is an iconic French palace located on the Right Bank of the Seine in Paris, occupying a vast expanse of land between the Tuileries Gardens and t ...

and trampled to death. De Staël offered baron Malouet a plan of escape for the royal family. As there was no government, militant members of the Insurrectionary Commune were given extensive police powers from the provisional, executive council, " to detain, interrogate and incarcerate suspects without anything resembling due process of law". She helped De Narbonne, dismissed for plotting, to hide under the altar in the chapel in the Swedish embassy, and lectured the sans-culottes

The (, 'without breeches') were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the . T ...

from the section in the hall.

On Sunday 2 September, the day the Elections for the National Convention and the September massacres

The September Massacres were a series of killings of prisoners in Paris that occurred in 1792, from Sunday, 2 September until Thursday, 6 September, during the French Revolution. Between 1,176 and 1,614 people were killed by '' fédérés'', gu ...

began, she fled herself in the garb of an ambassadress. Her carriage was stopped and the crowd forced her into the Paris town hall, where Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

presided. That same evening she was conveyed home, escorted by the procurator Louis Pierre Manuel. The next day the commissioner to the Commune of Paris Jean-Lambert Tallien arrived with a new passport and accompanied her to the edge of the barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denot ...

.

Salons at Coppet and Paris

After her flight from Paris, de Staël moved to

After her flight from Paris, de Staël moved to Rolle

Rolle () is a municipality in the Canton of Vaud in Switzerland. It was the seat of the district of Rolle until 2006, when it became part of the district of Nyon. It is located on the northwestern shore of Lake Geneva (''Lac Léman'') between Ny ...

in Switzerland, where Albert was born. She was supported by de Montmorency and the Marquis de Jaucourt, whom she had previously supplied with Swedish passports. In January 1793, she made a four-month visit to England to be with her then-lover, the Comte de Narbonne, at Juniper Hall

Juniper Hall FSC Field Centre is an 18th-century country house, leased from the National Trust, on the east slopes of Mickleham in the deep Mole Gap of the North Downs in Surrey, England. The varying contours of the slopes provide habitats ...

. (Since 1 February, France and Great Britain had been at war.) Within a few weeks, she was pregnant; it was apparently one of the reasons for the scandal she caused in England. According to Fanny Burney, the result was that her father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

urged Fanny to avoid the company of de Staël and her circle of French Émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French verb ''émigrer'' meaning "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled Fran ...

s in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

. De Staël met Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole (), 4th Earl of Orford (24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English writer, art historian, man of letters, antiquarian, and Whig politician.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twi ...

, James Mackintosh, Lord Sheffield, a friend of Edward Gibbon, and Lord Loughborough, the new Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

. She was not impressed with the condition of women in English society. Individual freedom was as important to her as were abstract political liberties.

In the summer of 1793, de Staël returned to Switzerland, probably because De Narbonne had cooled towards her. She published a defence of the character of

In the summer of 1793, de Staël returned to Switzerland, probably because De Narbonne had cooled towards her. She published a defence of the character of Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

, entitled, ''Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine'', 1793 ("Reflections on the Queen's trial"). In de Staël's view, France should have adapted from an absolute Absolute may refer to:

Companies

* Absolute Entertainment, a video game publisher

* Absolute Radio, (formerly Virgin Radio), independent national radio station in the UK

* Absolute Software Corporation, specializes in security and data risk manag ...

to a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

as was the case in England. Living in Jouxtens-Mézery

Jouxtens-Mézery is a municipality in the district of Lausanne in the canton of Vaud in Switzerland.

It is a suburb of the city of Lausanne.

History

Jouxtens is first mentioned in 1185 as ''Jotens''. Mézery is first mentioned in 929 as '' ...

, farther away from the French border than Coppet, Germaine was visited by Adolph Ribbing

{{Infobox noble, type

, name = Adolph Ribbing

, title = Count

, image = Adolph Ribbing.jpg

, caption = Adolph Ludvig Ribbing

, alt =

, CoA =

, more = n ...

. Count Ribbing was living in exile, after his conviction for taking part in a conspiracy to assassinate the Swedish king, Gustav III

Gustav III (29 March 1792), also called ''Gustavus III'', was King of Sweden from 1771 until his assassination in 1792. He was the eldest son of Adolf Frederick of Sweden and Queen Louisa Ulrika of Prussia.

Gustav was a vocal opponent of what ...

. In September 1794, the recently divorced Benjamin Constant

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (; 25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), or simply Benjamin Constant, was a Franco-Swiss political thinker, activist and writer on political theory and religion.

A committed republican from 1795, he backed t ...

visited her, wanting to meet her before he committed suicide.

In May 1795, de Staël moved to Paris, now with Constant in tow, as her protégé and lover. De Staël rejected the idea of the right of resistance – which had been introduced into the never implemented French Constitution of 1793, and was removed from the Constitution of 1795. In 1796, she published ''Sur l'influence des passions'', in which she praised suicide, a book which attracted the attention of the German writers Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, and philosopher. During the last seventeen years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller developed a productive, if complicated, friends ...

and Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

.

Still absorbed by French politics, de Staël reopened her salon. It was during these years that Mme de Staël arguably exerted most political influence. For a time she was still visible in the diverse and eccentric society of the mid-1790s. However, on the 13 Vendémiaire

13 Vendémiaire Year 4 in the French Republican Calendar (5 October 1795 in the Gregorian calendar) is the name given to a battle between the French Revolutionary troops and Royalist forces in the streets of Paris. This battle was part of the ...

the ''Comité de salut public

The Committee of Public Safety (french: link=no, Comité de salut public) was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. S ...

'' ordered her to leave Paris after accusations of politicking, and put Constant in detention for one night. De Staël spent that autumn in the spa of Forges-les-Eaux

Forges-les-Eaux () is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in northern France. On 1 January 2016, the former commune of Le Fossé was merged into Forges-les-Eaux.

Geography

A farming and spa town, with considerable ...

. She was considered a threat to political stability and mistrusted by both sides in the political conflict. The couple moved to Ormesson-sur-Marne

Ormesson-sur-Marne (, literally ''Ormesson on Marne'') is a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris.

Transport

Ormesson-sur-Marne is served by no station of the Paris Métro, RER, or suburba ...

where they stayed with Mathieu Montmorency. In Summer 1796 Constant founded the "Cercle constitutionnel" in Luzarches with de Staël's support. In May 1797, she was back in Paris and eight months pregnant. She succeeded in getting Talleyrand from the list of Émigrés and on his return from the United States to have him appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs in July. From the coup of 18 Fructidor

The Coup of 18 Fructidor, Year V (4 September 1797 in the French Republican Calendar), was a seizure of power in France by members of the Directory, the government of the French First Republic, with support from the French military. The coup wa ...

it was announced that anyone campaigning to restore the monarchy or the French Constitution of 1793 would be shot without trial. Germaine moved to Saint-Ouen, on her father's estate and became a close friend of the beautiful and wealthy Juliette Récamier

Jeanne Françoise Julie Adélaïde Récamier (; 3 December 1777 – 11 May 1849), known as Juliette (), was a French socialite whose salon drew people from the leading literary and political circles of early 19th-century Paris. As an icon of ...

to whom she sold her parents' house in the Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin

This "quartier" of Paris got its name from the rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. It runs north-northwest from the Boulevard des Italiens to the Église de la Sainte-Trinité, Paris, Église de la Sainte-Trinité.

In ...

.

De Staël completed the initial part of her first most substantial contribution to political and constitutional theory, "Of present circumstances that can end the Revolution, and of the principles that must found the republic of France".

Conflict with Napoleon

On 6 December 1797 de Staël had the first meeting with Napoleon Bonaparte in Talleyrand's office and met him again on 3 January 1798 during a ball. She made it clear to him that she did not agree with his planned invasion of Switzerland. He ignored her opinions and would not read her letters. In January 1800, Napoleon appointed Benjamin Constant a member of the Tribunat; not long after, Constant became his enemy. Two years later, Napoleon forced him into exile on account of his speeches which he took to be actually written by Mme de Staël. In August 1802, Napoleon was electedfirst consul

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Co ...

for life. This put de Staël into opposition to him both for personal and political reasons. In her view, Napoleon had begun to resemble Machiavelli; while for Napoleon, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

, J.J. Rousseau and their followers were the cause of the French Revolution. This view was cemented when Jacques Necker published his "Last Views on Politics and Finance" and his daughter, her "De la littérature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales". It was her first philosophical treatment of the Europe question: it dealt with such factors as nationality, history, and social institutions. Napoleon started a campaign against her latest publication. He did not like her cultural determinism

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

and generalization

A generalization is a form of abstraction whereby common properties of specific instances are formulated as general concepts or claims. Generalizations posit the existence of a domain or set of elements, as well as one or more common character ...

s, in which she stated that "an artist must be of his own time".Anne-Louise-Germaine Necker, Baroness de Staël-Holstein (1766–1817) by Petri Liukkonen/ref> In his opinion a woman should stick to knitting. He said about her, according to the Memoirs of Madame de Rémusat, that she "teaches people to think who had never thought before, or who had forgotten how to think". It became clear that the first man of France and de Staël were not likely ever to get along together. De Staël published a provocative, anti-Catholic novel '' Delphine'', in which the ''femme incomprise'' (misunderstood woman) living in Paris between 1789 and 1792, is confronted with conservative ideas about divorce after the

Concordat of 1801

The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII, signed on 15 July 1801 in Paris. It remained in effect until 1905, except in Alsace-Lorraine, where it remains in force. It sought national reconciliation ...

. In this tragic novel, influenced by Goethe's ''The Sorrows of Young Werther

''The Sorrows of Young Werther'' (; german: Die Leiden des jungen Werthers) is a 1774 epistolary novel by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, which appeared as a revised edition in 1787. It was one of the main novels in the '' Sturm und Drang'' period in Ge ...

'' and Rousseau's ''Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse

''Julie; or, The New Heloise'' (french: Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse), originally entitled ''Lettres de Deux Amans, Habitans d'une petite Ville au pied des Alpes'' ("Letters from two lovers, living in a small town at the foot of the Alps"), is ...

'', she reflects on the legal and practical aspects on divorce, the arrests and the September Massacres

The September Massacres were a series of killings of prisoners in Paris that occurred in 1792, from Sunday, 2 September until Thursday, 6 September, during the French Revolution. Between 1,176 and 1,614 people were killed by '' fédérés'', gu ...

, and the fate of the émigrés. (During the winter of 1794 it seems De Staël was pondering a divorce and whether to marry Ribbing.) The main characters have traits of the unstable Benjamin Constant, and Talleyrand is depicted as an old woman, herself as the heroine with the liberal view of the Italian aristocrat and politician Melzi d'Eril

Francesco Melzi d'Eril, Duke of Lodi, Count of Magenta (6 March 1753 – 16 January 1816) was an Italian politician and patriot, serving as vice-president of the Napoleonic Italian Republic (1802–1805). He was a consistent supporter of the Ita ...

.

When Constant moved to Maffliers in September 1803 de Staël went to see him and let Napoleon know she would be wise and cautious. Thereupon her house immediately became popular again among her friends, but Napoleon, informed by Madame de Genlis Madame may refer to:

* Madam, civility title or form of address for women, derived from the French

* Madam (prostitution), a term for a woman who is engaged in the business of procuring prostitutes, usually the manager of a brothel

* ''Madame'' ( ...

, suspected a conspiracy. "Her extensive network of connections – which included foreign diplomats and known political opponents, as well as members of the government and of Bonaparte's own family – was in itself a source of suspicion and alarm for the government." Her protection of Jean Gabriel Peltier – who plotted the death of Napoleon – influenced his decision on 13 October 1803 to exile her without trial.

Years of exile

For ten years, de Staël was not allowed to come within 40 leagues (almost 200 km) of Paris. She accused Napoleon of "persecuting a woman and her children". On 23 October, she left for Germany "out of pride", in the hope of gaining support and to be able to return home as soon as possible.German travels

With her children and Constant, de Staël stopped off in

With her children and Constant, de Staël stopped off in Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

and met Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

's French translator Charles de Villers. In mid-December, they arrived in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together with the neighbouri ...

, where she stayed for two and a half months at the court of the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (german: Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach) was a historical German state, created as a duchy in 1809 by the merger of the Ernestine duchies of Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Eisenach, which had been in personal union since 1741. It was raised ...

and his mother Anna Amalia. Goethe who had become ill hesitated about seeing her. After meeting her, Goethe went on to refer to her as an "extraordinary woman" in his private correspondence. Schiller complimented her intelligence and eloquence, but her frequent visits distracted him from completing ''William Tell''. De Staël was constantly on the move, talking and asking questions. Constant decided to abandon her in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

and return to Switzerland. De Staël travelled on to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, where she made the acquaintance of August Schlegel

August Wilhelm (after 1812: von) Schlegel (; 8 September 176712 May 1845), usually cited as August Schlegel, was a German poet, translator and critic, and with his brother Friedrich Schlegel the leading influence within Jena Romanticism. His trans ...

who was lecturing there on literature. She appointed him on an enormous salary to tutor her children. On 18 April they all left Berlin when the news of her father's death reached her.

Mistress of Coppet

On 19 May, de Staël arrived in Coppet now its wealthy and independent mistress. She spent the summer at the chateau sorting through his writings and published an essay on his private life. In April 1804,Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel (; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figure ...

married Dorothea Veit

Dorothea Friederike von Schlegel (; 24 October 1764 – 3 August 1839) was a German novelist and translator.

Life

She was born as Brendel Mendelssohn in 1764 in Berlin.In older literature and on her gravestone one finds the date 1763, but this i ...

in the Swedish embassy. In July Constant wrote about her, "She exerts over everything around her a kind of inexplicable but real power. If only she could govern herself, she might have governed the world." In December 1804 she travelled to Italy, accompanied by her children, Schlegel, and the historian Sismondi. There she met the poet Monti and the painter, Angelica Kauffman

Maria Anna Angelika Kauffmann ( ; 30 October 1741 – 5 November 1807), usually known in English as Angelica Kauffman, was a Swiss Neoclassical painter who had a successful career in London and Rome. Remembered primarily as a history painter, K ...

. "Her visit to Italy helped her to develop her theory of the difference between northern and southern societies..."

De Staël returned to Coppet in June 1805, moved to Meulan

Meulan-en-Yvelines (; formerly just ''Meulan'') is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region in north-central France. It hosted part of the sailing events for the 1900 Summer Olympics held in neighboring Paris, and would ...

(Château d'Acosta), and spent nearly a year writing her next book on Italy's culture and history. In '' Corinne, ou L'Italie'' (1807), her own impressions of a sentimental and intellectual journey, the heroine appears to have been inspired by the Italian poet Diodata Saluzzo Roero. She combined romance with travelogue, showed all of Italy's works of art still in place, rather than plundered by Napoleon and taken to France. The book's publication acted as a reminder of her existence, and Napoleon sent her back to Coppet. Her house became, according to Stendhal

Marie-Henri Beyle (; 23 January 1783 – 23 March 1842), better known by his pen name Stendhal (, ; ), was a 19th-century French writer. Best known for the novels ''Le Rouge et le Noir'' ('' The Red and the Black'', 1830) and ''La Chartreuse de ...

, "the general headquarters of European thought" and was a debating club hostile to Napoleon, "turning conquered Europe into a parody of a feudal empire, with his own relatives in the roles of vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back t ...

s". Madame Récamier, also banned by Napoleon, Prince Augustus of Prussia, Charles Victor de Bonstetten, and Chateaubriand all belonged to the "Coppet group

The Coppet group (''Groupe de Coppet''), also known as the Coppet circle, was an informal intellectual and literary gathering centred on Germaine de Staël during the time period between the establishment of the Napoleonic First Empire (1804) a ...

". Each day the table was laid for about thirty guests. Talking seemed to be everybody's chief activity.

For a time de Staël lived with Constant in Auxerre

Auxerre ( , ) is the capital of the Yonne department and the fourth-largest city in Burgundy. Auxerre's population today is about 35,000; the urban area (''aire d'attraction'') comprises roughly 113,000 inhabitants. Residents of Auxerre are r ...

(1806), Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

(1807), Aubergenville

Aubergenville () is a commune in the Yvelines department in north-central France. It is located between Mantes-la-Jolie and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in the valley of the Seine. This city is located near the Côteau de Montgardé on the road to ...

(1807). Then she met Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel (; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figure ...

, whose wife Dorothea had translated ''Corinne'' into German. The use of the word Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

was invented by Schlegel but spread more widely across France through its persistent use by de Staël. Late in 1807 she set out for Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and visited Maurice O'Donnell. She was accompanied by her children and August Schlegel who gave his famous lectures there. In 1808 Benjamin Constant was afraid to admit to her that he had married Charlotte von Hardenberg in the meantime. "If men had the qualities of women", de Staël wrote, "love would simply cease to be a problem." De Staël set to work on her book about Germany – in which she presented the idea of a state called "Germany" as a model of ethics and aesthetics and praised German literature and philosophy. The exchange of ideas and literary and philosophical conversations with Goethe, Schiller, and Wieland had inspired de Staël to write one of the most influential books of the nineteenth century on Germany.Fontana

Fontana may refer to:

Places

Italy

*Fontana Liri, comune in the Province of Frosinone

*Fontanafredda, comune in the Province of Pordenone

*Fontanarosa, comune in the Province of Avellino

*Francavilla Fontana, comune in the Province of Brindisi

* ...

, p. 206

Return to France

Pretending she wanted to emigrate to the United States, de Staël was given permission to re-enter France. She moved first into theChâteau de Chaumont

The Château de Chaumont (), officially Château de Chaumont-sur-Loire, is a castle (''château'') in Chaumont-sur-Loire, Centre-Val de Loire, France. The castle was founded in the 10th century by Odo I, Count of Blois. After Pierre d'Ambois ...

(1810), then relocated to Fossé and Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a subprefecture of the department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the main towns along the river Loir. The river divides itself at the ...

. She was determined to publish ''De l'Allemagne

''On Germany'' (french: De l'Allemagne), also known in English as ''Germany'', is a book about German culture and in particular German Romanticism, written by the French writer Germaine de Staël. It promotes Romantic literature, introducing t ...

'' in France, a book in which she called French political structures into question, so indirectly criticizing Napoleon. Constrained by censorship, she wrote to the emperor a letter of complaint. The minister of police Savary had emphatically forbidden her to publish her “un-French" book. In October 1810 de Staël was exiled again and had to leave France within three days. August Schlegel

August Wilhelm (after 1812: von) Schlegel (; 8 September 176712 May 1845), usually cited as August Schlegel, was a German poet, translator and critic, and with his brother Friedrich Schlegel the leading influence within Jena Romanticism. His trans ...

was also ordered to leave the Swiss Confederation as an enemy of French literature. She found consolation in a wounded veteran officer named Albert de Rocca

Albert Jean Michel de Rocca (1788 – 31 January 1818) was a French lieutenant during the Napoleonic Wars. He was also the second husband of Anne Louise Germaine de Staël.

Biography

De Rocca was born in Geneva, Republic of Geneva, in 1788. He se ...

, twenty-three years her junior, to whom she got privately engaged in 1811 but did not marry publicly until 1816.

East European travels

The operations of the French imperial police in the case of de Staël are rather obscure. She was at first left undisturbed, but by degrees, the chateau itself became a source of suspicion, and her visitors found themselves heavily persecuted. François-Emmanuel Guignard, De Montmorency and Mme Récamier were exiled for the crime of visiting her. She remained at home during the winter of 1811, planning to escape to England or Sweden with the manuscript. On 23 May 1812, she left Coppet under the pretext of a short outing, but journeyed through

The operations of the French imperial police in the case of de Staël are rather obscure. She was at first left undisturbed, but by degrees, the chateau itself became a source of suspicion, and her visitors found themselves heavily persecuted. François-Emmanuel Guignard, De Montmorency and Mme Récamier were exiled for the crime of visiting her. She remained at home during the winter of 1811, planning to escape to England or Sweden with the manuscript. On 23 May 1812, she left Coppet under the pretext of a short outing, but journeyed through Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

, Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; bar, Innschbruck, label=Austro-Bavarian ) is the capital of Tyrol and the fifth-largest city in Austria. On the River Inn, at its junction with the Wipp Valley, which provides access to the Brenner Pass to the south, it had a p ...

and Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Austro-Bavarian) is the fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the Roman settlement of ''Iuvavum''. Salzburg was founded ...

to Vienna, where she met Metternich. There, after some trepidation and trouble, she received the necessary passports to go on to Russia.

During Napoleon's invasion of Russia, de Staël, her two children, and Schlegel travelled through Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

in the Habsburg empire from Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

to Łańcut

Łańcut (, approximately "wine-suit"; yi, לאַנצוט, Lantzut; uk, Ла́ньцут, Lánʹtsut; german: Landshut) is a town in south-eastern Poland, with 18,004 inhabitants, as of 2 June 2009. Situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship ( ...

where de Rocca, having deserted the French army and having been searched by the French gendarmerie

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (literally, ...

, was waiting for her. The journey continued to Lemberg

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

. On 14 July 1812 they arrived in Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

. In the meantime, Napoleon, who took a more northern route, had crossed the Niemen River with his army. In Kyiv, she met Miloradovich

Count Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich (russian: Граф Михаи́л Андре́евич Милора́дович, sh-Cyrl, Гроф Михаил Андрејевић Милорадовић ''Grof Mihail Andrejević Miloradović''; – ...

, governor of the city. De Staël hesitated to travel on to Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, and decided instead to go north. Perhaps she was informed of the outbreak of plague in the Ottoman Empire. In Moscow, she was invited by the governor Fyodor Rostopchin

Count Fyodor Vasilyevich Rostopchin (russian: Фёдор Васильевич Ростопчин) ( – ) was a Russian statesman and General of the Infantry who served as the Governor-General of Moscow during the French invasion of Russia. ...

. According to de Staël, it was Rostopchin who ordered his mansion in Italian style near Winkovo to be set on fire. She left only a few weeks before Napoleon arrived there. Until 7 September, her party stayed in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. According to John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, the American ambassador in Russia, her sentiments appeared to be as much the result of personal resentment against Bonaparte as of her general views of public affairs. She complained that he would not let her live in peace anywhere, merely because she had not praised him in her works. She met twice with the tsar Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first King of Congress Poland from 1815, and the Grand Duke of Finland from 1809 to his death. He was the eldest son of Emperor Paul I and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg.

The son o ...

who "related to me also the lessons a la Machiavelli which Napoleon had thought proper to give him."

For de Staël, that was a vulgar and vicious theory. General Kutuzov

Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov ( rus, Князь Михаи́л Илларио́нович Голени́щев-Куту́зов, Knyaz' Mikhaíl Illariónovich Goleníshchev-Kutúzov; german: Mikhail Illarion Golenishchev-Kut ...

sent her letters from the Battle of Tarutino

The Battle of Tarutino (russian: Тарутинo) was a part of Napoleon's invasion of Russia. In the battle Russian troops under the command of Bennigsen defeated French troops under the command of Joachim Murat.

The battle is sometimes ca ...

; before the end of that year he succeeded, aided by the extreme weather, in chasing the Grande Armée

''La Grande Armée'' (; ) was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Em ...

out of Russia.

After four months of travel, de Staël arrived in Sweden. In Stockholm, she began writing her "Ten Years' Exile", detailing her travels and encounters. She did not finish the manuscript and after eight months, she set out for England, without August Schlegel, who meanwhile had been appointed secretary to the Crown Prince Carl Johan, formerly French Marshal

After four months of travel, de Staël arrived in Sweden. In Stockholm, she began writing her "Ten Years' Exile", detailing her travels and encounters. She did not finish the manuscript and after eight months, she set out for England, without August Schlegel, who meanwhile had been appointed secretary to the Crown Prince Carl Johan, formerly French Marshal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte

Charles XIV John ( sv, Karl XIV Johan; born Jean Bernadotte; 26 January 1763 – 8 March 1844) was King of Sweden and Norway from 1818 until his death in 1844. Before his reign he was a Marshal of France during the Napoleonic Wars and participat ...

(She supported Bernadotte as the new ruler of France, as she hoped he would introduce a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

). In London she received a great welcome. She met Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

, William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

, the abolitionist, and Sir Humphry Davy, the chemist and inventor. According to Byron, "She preached English politics to the first of our English Whig politicians ... preached politics no less to our Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

politicians the day after." In March 1814 she invited Wilberforce for dinner and devoted the remaining years of her life to the fight for the abolition of the slave trade. Her stay was severely marred by the death of her son Albert, who as a member of the Swedish army had fallen in a duel with a Cossack officer in Doberan as a result of a gambling dispute. In October John Murray published ''De l'Allemagne'' both in French and English translation, in which she reflected on nationalism and suggested a re-consideration of cultural rather than natural boundaries. In May 1814, after Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

had been crowned (Bourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* Ab ...

) she returned to Paris. She wrote her ''Considérations sur la révolution française'', based on Part One of "Ten Years' Exile". Again her salon became a major attraction both for Parisians and foreigners.

Restoration and death

When news came of Napoleon's landing on the Côte d'Azur, between

When news came of Napoleon's landing on the Côte d'Azur, between Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. The ...

and Antibes

Antibes (, also , ; oc, label= Provençal, Antíbol) is a coastal city in the Alpes-Maritimes department of southeastern France, on the Côte d'Azur between Cannes and Nice.

The town of Juan-les-Pins is in the commune of Antibes and the Sop ...

, early in March 1815, de Staël fled again to Coppet, and never forgave Constant for approving of Napoleon's return. Although she had no affection for the Bourbons

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

she succeeded in obtaining restitution for the huge loan Necker had made to the French state in 1778 before the Revolution (see above). In October, after the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

, she set out for Italy, not only for the sake of her own health but for that of her second husband, de Rocca, who was suffering from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

. In May her 19-year-old daughter Albertine married Victor, 3rd duc de Broglie in Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 158,493 residents in December 2017. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn (pronou ...

.

The whole family returned to Coppet in June. Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

, at that time in debt, left London in great trouble and frequently visited de Staël during July and August. For Byron, she was Europe's greatest living writer, but "with her pen behind her ears and her mouth full of ink". "Byron was particularly critical of de Staël's self-dramatizing tendencies". Byron was a supporter of Napoleon, but for de Staël Bonaparte "was not only a talented man but also one who represented a whole pernicious system of power", a system that "ought to be examined as a great political problem relevant to many generations." "Napoleon imposed standards of homogeneity on Europe that is, French taste in literature, art and the legal systems, all of which de Staël saw as inimical to her cosmopolitan point of view." Byron wrote she was "sometimes right and often wrong about Italy and England – but almost always true in delineating the heart, which is of but one nation of no country, or rather, of all."

Despite her increasingly ill health, de Staël returned to Paris for the winter of 1816–17, living at 40, rue des Mathurins. Constant argued with de Staël, who had asked him to pay off his debts to her. A warm friendship sprang up between de Staël and the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister ...

, whom she had first met in 1814, and she used her influence with him to have the size of the Army of Occupation greatly reduced.

De Staël became confined to her house, paralyzed since 21 February 1817 following a stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

. She died on 14 July 1817. Her deathbed conversion to Roman Catholicism, after reading Thomas à Kempis

Thomas à Kempis (c. 1380 – 25 July 1471; german: Thomas von Kempen; nl, Thomas van Kempen) was a German-Dutch canon regular of the late medieval period and the author of '' The Imitation of Christ'', published anonymously in Latin in the ...

, was reported but is subject to some debate. Wellington remarked that, while he knew that she was greatly afraid of death, he had thought her incapable of believing in the afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving es ...

. Wellington makes no mention of de Stael reading Thomas à Kempis in the quote found in Elizabeth Longford's biography of the Iron Duke. Furthermore, he reports hearsay, which may explain why two modern biographies of de Staël – Herold and Fairweather – discount the conversion entirely. Herold states that "her last deed in life was to reaffirm in her "Considerations, her faith in Enlightenment, freedom, and progress." Fairweather makes no mention of the conversion at all. Rocca survived her by little more than six months.

Offspring

Besides two daughters, Gustava Sofia Magdalena (born July 1787) and Gustava Hedvig (born August 1789), both died in infancy, de Staël had two sons, Ludwig August (1790–1827), Albert (1792–1813), and a daughter, Albertine, baroness Staël von Holstein (1797–1838). It is believed Louis, Comte de Narbonne-Lara was the father of Ludvig August and Albert, and Benjamin Constant the father of red-haired Albertine. With Albert de Rocca, de Staël then aged 46, had one son, the disabled Louis-Alphonse de Rocca (1812–1842), who married Marie-Louise-Antoinette de Rambuteau, daughter of

Besides two daughters, Gustava Sofia Magdalena (born July 1787) and Gustava Hedvig (born August 1789), both died in infancy, de Staël had two sons, Ludwig August (1790–1827), Albert (1792–1813), and a daughter, Albertine, baroness Staël von Holstein (1797–1838). It is believed Louis, Comte de Narbonne-Lara was the father of Ludvig August and Albert, and Benjamin Constant the father of red-haired Albertine. With Albert de Rocca, de Staël then aged 46, had one son, the disabled Louis-Alphonse de Rocca (1812–1842), who married Marie-Louise-Antoinette de Rambuteau, daughter of Claude-Philibert Barthelot de Rambuteau

Claude-Philibert Barthelot, comte de Rambuteau () (Mâcon, 9 November 1781 – Château de Rambuteau, 11 April 1869) was a French senior official of the first half of the 19th century. He was Préfet of the former Départment of the Seine, ...

, and granddaughter of De Narbonne. Even as she gave birth, there were fifteen people in her bedroom.

After the death of de Staël's husband, Mathieu de Montmorency became the legal guardian of her children. Like August Schlegel he was one of her intimates until the end of her life.

Legacy

Albertine Necker de Saussure

Albertine Adrienne Necker de Saussure (9 April 1766, in Geneva – 13 April 1841, in Mornex, on the Salève, near Geneva) was a Genevan and then Swiss writer and educationalist, and an early advocate of education for women.

Life

Albertine Necker ...

, married to de Staël's cousin, wrote her biography in 1821, published as part of the collected works. Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense ...