George Stephenson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British

Their first child

Their first child

In 1815, aware of the explosions often caused in mines by naked flames, Stephenson began to experiment with a safety lamp that would burn in a gaseous atmosphere without causing an explosion. At the same time, the eminent scientist and Cornishman

In 1815, aware of the explosions often caused in mines by naked flames, Stephenson began to experiment with a safety lamp that would burn in a gaseous atmosphere without causing an explosion. At the same time, the eminent scientist and Cornishman

Stephenson designed his first locomotive in 1814, a travelling engine designed for hauling coal on the Killingworth wagonway named '' Blücher'' after the

Stephenson designed his first locomotive in 1814, a travelling engine designed for hauling coal on the Killingworth wagonway named '' Blücher'' after the  The new engines were too heavy to run on wooden rails or plate-way, and iron edge rails were in their infancy, with

The new engines were too heavy to run on wooden rails or plate-way, and iron edge rails were in their infancy, with

In 1821, a parliamentary bill was passed to allow the building of the

In 1821, a parliamentary bill was passed to allow the building of the  A manufacturer was needed to provide the locomotives for the line. Pease and Stephenson had jointly established a company in Newcastle to manufacture locomotives. It was set up as

A manufacturer was needed to provide the locomotives for the line. Pease and Stephenson had jointly established a company in Newcastle to manufacture locomotives. It was set up as

Stephenson had ascertained by experiments at Killingworth that half the power of the locomotive was consumed by a gradient as little as 1 in 260. He concluded that railways should be kept as level as possible. He used this knowledge while working on the

Stephenson had ascertained by experiments at Killingworth that half the power of the locomotive was consumed by a gradient as little as 1 in 260. He concluded that railways should be kept as level as possible. He used this knowledge while working on the

1830 also saw the grand opening of the skew bridge in Rainhill over the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The bridge was the first to cross any railway at an angle. It required the structure to be constructed as two flat planes (overlapping in this case by ) between which the stonework forms a parallelogram shape when viewed from above. It has the effect of flattening the arch and the solution is to lay the bricks forming the arch at an angle to the abutments (the piers on which the arches rest). The technique, which results in a spiral effect in the arch masonry, provides extra strength in the arch to compensate for the angled abutments.

The bridge is still in use at Rainhill station, and carries traffic on the A57 (Warrington Road). The bridge is a listed structure.

1830 also saw the grand opening of the skew bridge in Rainhill over the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The bridge was the first to cross any railway at an angle. It required the structure to be constructed as two flat planes (overlapping in this case by ) between which the stonework forms a parallelogram shape when viewed from above. It has the effect of flattening the arch and the solution is to lay the bricks forming the arch at an angle to the abutments (the piers on which the arches rest). The technique, which results in a spiral effect in the arch masonry, provides extra strength in the arch to compensate for the angled abutments.

The bridge is still in use at Rainhill station, and carries traffic on the A57 (Warrington Road). The bridge is a listed structure.

George Stephenson moved to the parish of Alton Grange (now part of Ravenstone) in Leicestershire in 1830, originally to consult on the

George Stephenson moved to the parish of Alton Grange (now part of Ravenstone) in Leicestershire in 1830, originally to consult on the

George Stephenson's Birthplace is an 18th-century

George Stephenson's Birthplace is an 18th-century

Biography

Stephenson's birthplace

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stephenson, George 1781 births 1848 deaths People of the Industrial Revolution 19th-century British inventors Millwrights People from Wylam Burials in Derbyshire 19th-century British engineers English civil engineers English mechanical engineers

civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

and mechanical engineer

Mechanical may refer to:

Machine

* Machine (mechanical), a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement

* Mechanical calculator, a device used to perform the basic operations of ...

. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian ...

a great example of diligent application and thirst for improvement. Self-help

Self-help or self-improvement is a self-guided improvement''APA Dictionary of Physicology'', 1st ed., Gary R. VandenBos, ed., Washington: American Psychological Association, 2007.—economically, intellectually, or emotionally—often with a subs ...

advocate Samuel Smiles

Samuel Smiles (23 December 1812 – 16 April 1904) was a British author and government reformer. Although he campaigned on a Chartist platform, he promoted the idea that more progress would come from new attitudes than from new laws. His prim ...

particularly praised his achievements. His chosen rail gauge

In rail transport, track gauge (in American English, alternatively track gage) is the distance between the two rails of a railway track. All vehicles on a rail network must have wheelsets that are compatible with the track gauge. Since many ...

, sometimes called "Stephenson gauge", was the basis for the standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), International gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge and European gauge in Europe, and SGR in E ...

used by most of the world's railways.

Pioneered by Stephenson, rail transport

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

was one of the most important technological inventions of the 19th century and a key component of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. Built by George and his son Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

's company Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company was a locomotive manufacturing company founded in 1823 in Forth Street, Newcastle upon Tyne in England. It was the first company in the world created specifically to build railway engines.

Famous early locomoti ...

, the ''Locomotion'' No. 1 was the first steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, oil or, rarely, wood) to heat water in the loco ...

to carry passengers on a public rail line, the Stockton and Darlington Railway

The Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) was a railway company that operated in north-east England from 1825 to 1863. The world's first public railway to use steam locomotives, its first line connected collieries near Shildon with Darli ...

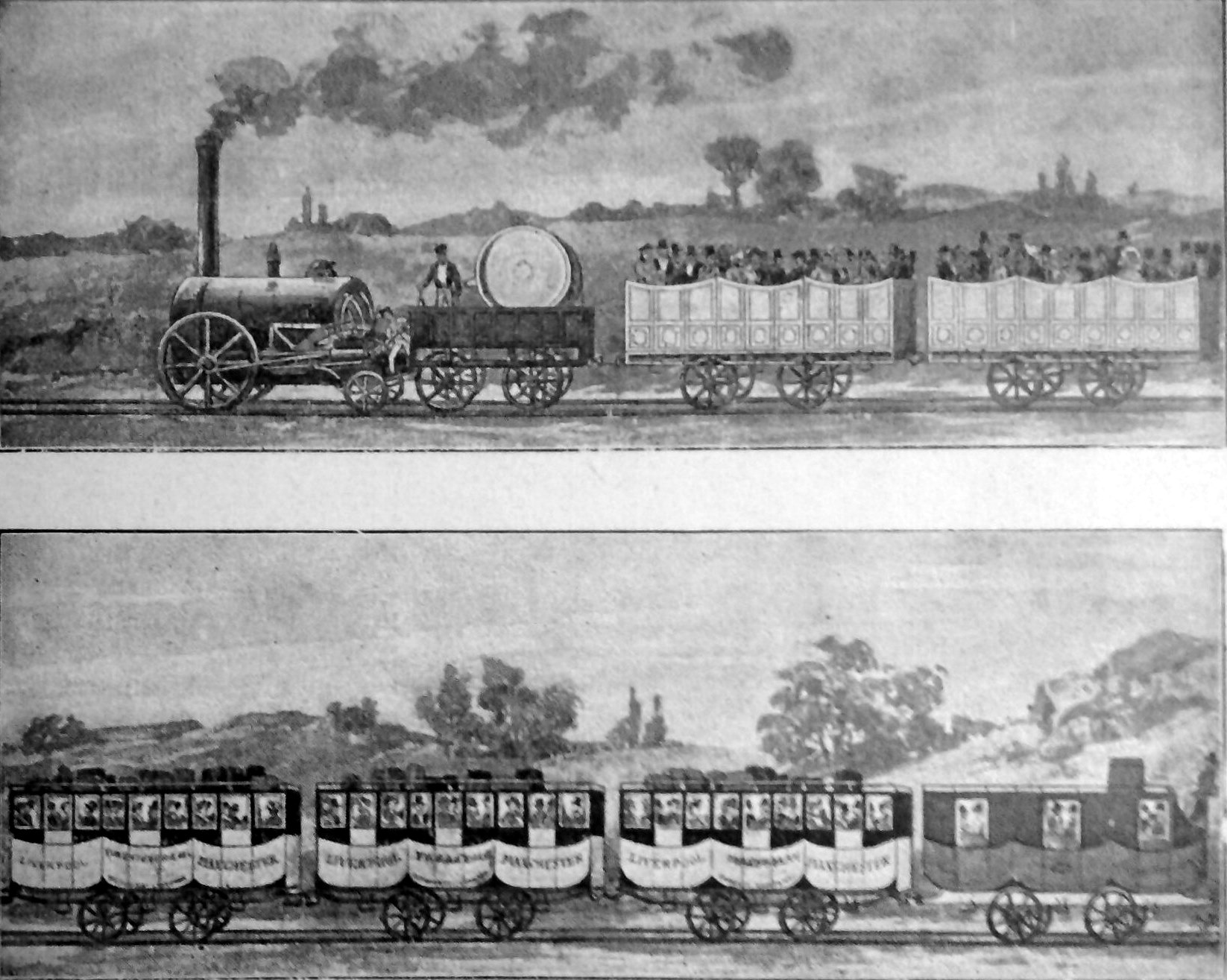

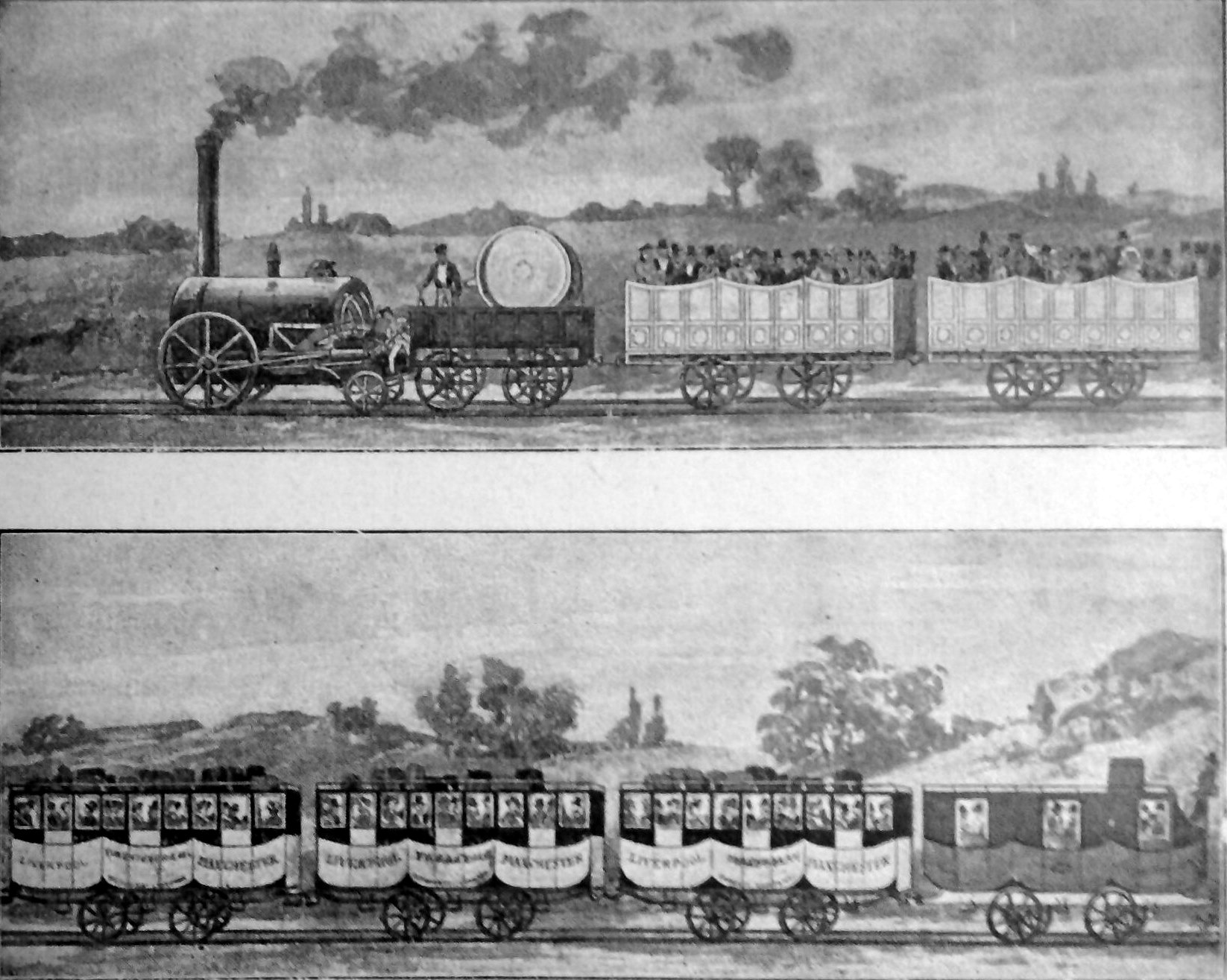

in 1825. George also built the first public inter-city railway line in the world to use locomotives, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was the first inter-city railway in the world. It opened on 15 September 1830 between the Lancashire towns of Liverpool and Manchester in England. It was also the first railway to rely exclusively ...

, which opened in 1830.

Childhood

George Stephenson was born on 9 June 1781 inWylam

Wylam is a village and civil parish in the county of Northumberland. It is located about west of Newcastle upon Tyne.

It is famous for the being the birthplace of George Stephenson, one of the early railway pioneers. George Stephenson's Bir ...

, Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

, which is 9 miles (15 km) west of Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

. He was the second child of Robert and Mabel Stephenson, neither of whom could read or write. Robert was the fireman for Wylam Colliery pumping engine, earning a very low wage, so there was no money for schooling. At 17, Stephenson became an engineman at Water Row Pit in Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

nearby. George realised the value of education and paid to study at night school to learn reading, writing and arithmetic – he was illiterate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, hum ...

until the age of 18.

In 1801 he began work at Black Callerton Colliery south of Ponteland

Ponteland ( ) is a large village and civil parish in Northumberland, England, north of Newcastle upon Tyne. The name means "island in the Pont", after the River Pont which flows from west to east and joins the River Blyth further downstream, be ...

as a 'brakesman', controlling the winding gear at the pit. In 1802 he married Frances Henderson and moved to Willington Quay, east of Newcastle. There he worked as a brakesman while they lived in one room of a cottage. George made shoes and mended clocks to supplement his income.

Their first child

Their first child Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

was born in 1803, and in 1804 they moved to Dial Cottage at West Moor

Forest Hall is a town in the borough of North Tyneside in the United Kingdom. It is a north eastern suburb of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle and lies six kilometres from the city centre. It borders Killingworth to the north, Holystone, Tyne and We ...

, near Killingworth

Killingworth, formerly Killingworth Township, is a town in North Tyneside, England.

Killingworth was built as a planned town in the 1960s, next to Killingworth Village, which existed for centuries before the Township. Other nearby towns an ...

where George worked as a brakesman at Killingworth Pit. Their second child, a daughter, was born in July 1805. She was named Frances after her mother. The child died after just three weeks and was buried in St Bartholomew's Church, Long Benton

St Bartholomew's Church, Long Benton is the Anglican parish church of Longbenton, in Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear. It is built in the Gothic Revival style.

Background

Whilst limited evidence exists of church activity round Benton from th ...

north of Newcastle.

In 1806 George's wife Frances died of consumption (tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

). She was buried in the same churchyard as their daughter on 16 May 1806, though the location of the grave is lost.

George decided to find work in Scotland and left Robert with a local woman while he went to work in Montrose. After a few months he returned, probably because his father was blinded in a mining accident. He moved back into a cottage at West Moor and his unmarried sister Eleanor moved in to look after Robert. In 1811 the pumping engine at High Pit, Killingworth was not working properly and Stephenson offered to improve it. He did so with such success that he was promoted to enginewright for the collieries at Killingworth, responsible for maintaining and repairing all the colliery engines. He became an expert in steam-driven machinery.

Early projects

The Safety Lamp

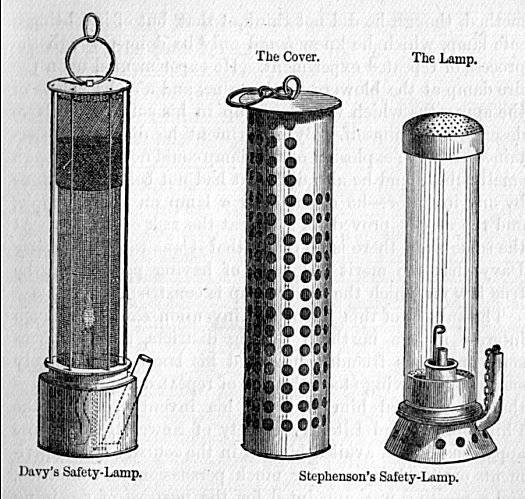

In 1815, aware of the explosions often caused in mines by naked flames, Stephenson began to experiment with a safety lamp that would burn in a gaseous atmosphere without causing an explosion. At the same time, the eminent scientist and Cornishman

In 1815, aware of the explosions often caused in mines by naked flames, Stephenson began to experiment with a safety lamp that would burn in a gaseous atmosphere without causing an explosion. At the same time, the eminent scientist and Cornishman Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for ...

was also looking at the problem. Despite his lack of scientific knowledge, Stephenson, by trial and error, devised a lamp in which the air entered via tiny holes, through which the flames of the lamp could not pass.

A month before Davy presented his design to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, Stephenson demonstrated his own lamp to two witnesses by taking it down Killingworth Colliery and holding it in front of a fissure from which firedamp was issuing. The two designs differed; Davy's lamp was surrounded by a screen of gauze, whereas Stephenson's prototype lamp had a perforated plate contained in a glass cylinder. For his invention Davy was awarded £2,000, whilst Stephenson was accused of stealing the idea from Davy, because he was not seen as an adequate scientist who could have produced the lamp by any approved scientific method.

Stephenson, having come from the North-East, spoke with a broad Northumberland accent and not the 'Language of Parliament,' which made him seem lowly. Realizing this, he made a point of educating his son Robert in a private school, where he was taught to speak in Standard English

In an English-speaking country, Standard English (SE) is the variety of English that has undergone substantial regularisation and is associated with formal schooling, language assessment, and official print publications, such as public servic ...

with a Received Pronunciation

Received Pronunciation (RP) is the accent traditionally regarded as the standard and most prestigious form of spoken British English. For over a century, there has been argument over such questions as the definition of RP, whether it is geo ...

accent. It was due to this, in their future dealings with Parliament, that it became clear that the authorities preferred Robert to his father.

A local committee of enquiry gathered in support of Stephenson, exonerated him, proved he had been working separately to create the 'Geordie

Geordie () is a nickname for a person from the Tyneside area of North East England, and the dialect used by its inhabitants, also known in linguistics as Tyneside English or Newcastle English. There are different definitions of what constitute ...

Lamp', and awarded him £1,000, but Davy and his supporters refused to accept their findings, and would not see how an uneducated man such as Stephenson could come up with the solution he had. In 1833 a House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

committee found that Stephenson had equal claim to having invented the safety lamp. Davy went to his grave believing that Stephenson had stolen his idea. The Stephenson lamp was used almost exclusively in North East England

North East England is one of nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. The region has three current administrative levels below the region level in the region; combined authority, unitary author ...

, whereas the Davy lamp was used everywhere else. The experience gave Stephenson a lifelong distrust of London-based, theoretical, scientific experts.

In his book ''George and Robert Stephenson'', the author L.T.C. Rolt relates that opinion varied about the two lamps' efficiency: that the Davy Lamp gave more light, but the Geordie Lamp was thought to be safer in a more gaseous atmosphere. He made reference to an incident at Oaks Colliery in Barnsley where both lamps were in use. Following a sudden strong influx of gas the tops of all the Davy Lamps became red hot (which had in the past caused an explosion, and in so doing risked another), whilst all the Geordie Lamps simply went out.

There is a theory that it was Stephenson who indirectly gave the name of Geordie

Geordie () is a nickname for a person from the Tyneside area of North East England, and the dialect used by its inhabitants, also known in linguistics as Tyneside English or Newcastle English. There are different definitions of what constitute ...

s to the people of the North East of England. By this theory, the name of the Geordie Lamp attached to the North East pit men themselves. By 1866 any native of Newcastle upon Tyne could be called a Geordie.

Locomotives

CornishmanRichard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He w ...

is credited with the first realistic design for a steam locomotive in 1802. Later, he visited Tyneside

Tyneside is a built-up area across the banks of the River Tyne in northern England. Residents of the area are commonly referred to as Geordies. The whole area is surrounded by the North East Green Belt.

The population of Tyneside as publishe ...

and built an engine there for a mine-owner. Several local men were inspired by this, and designed their own engines.

Stephenson designed his first locomotive in 1814, a travelling engine designed for hauling coal on the Killingworth wagonway named '' Blücher'' after the

Stephenson designed his first locomotive in 1814, a travelling engine designed for hauling coal on the Killingworth wagonway named '' Blücher'' after the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n general Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Fürst von Wahlstatt (; 21 December 1742 – 12 September 1819), ''Graf'' (count), later elevated to ''Fürst'' (sovereign prince) von Wahlstatt, was a Prussian '' Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal). He earne ...

(It was suggested the name sprang from Blücher's rapid march of his army in support of Wellington at Waterloo). ''Blücher'' was modelled on Matthew Murray

Matthew Murray (1765 – 20 February 1826) was an English steam engine and machine tool manufacturer, who designed and built the first commercially viable steam locomotive, the twin cylinder ''Salamanca'' in 1812. He was an innovative design ...

's locomotive ''Willington'', which George studied at Kenton and Coxlodge colliery on Tyneside, and was constructed in the colliery workshop behind Stephenson's home, Dial Cottage, on Great Lime Road. The locomotive could haul 30 tons of coal up a hill at , and was the first successful flanged-wheel adhesion locomotive: its traction depended on contact between its flanged wheels and the rail.

Altogether, Stephenson is said to have produced 16 locomotives at Killingworth, although it has not proved possible to produce a convincing list of all 16. Of those identified, most were built for use at Killingworth or for the Hetton colliery railway. A six-wheeled locomotive was built for the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway

The Kilmarnock and Troon Railway was an early railway line in Ayrshire, Scotland. It was constructed to bring coal from pits around Kilmarnock to coastal shipping at Troon Harbour, and passengers were carried.

It opened in 1812, and was the ...

in 1817 but was withdrawn from service because of damage to the cast-iron rails. Another locomotive was supplied to Scott's Pit railroad at Llansamlet

Llansamlet is a suburban district and community of Swansea, Wales, falling into the Llansamlet ward. The area is centred on the A48 road (named Samlet Road and Clase Road in the area) and the M4 motorway.

Like other places in Wales having a nam ...

, near Swansea

Swansea (; cy, Abertawe ) is a coastal city and the second-largest city of Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the C ...

, in 1819 but it too was withdrawn, apparently because it was under-boilered and again caused damage to the track.

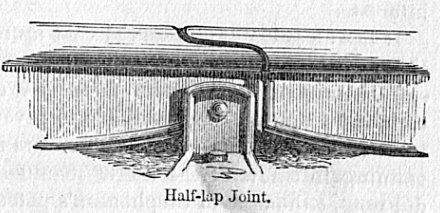

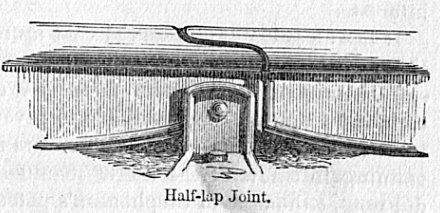

The new engines were too heavy to run on wooden rails or plate-way, and iron edge rails were in their infancy, with

The new engines were too heavy to run on wooden rails or plate-way, and iron edge rails were in their infancy, with cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

exhibiting excessive brittleness. Together with William Losh, Stephenson improved the design of cast-iron edge rails to reduce breakage; rails were briefly made by Losh, Wilson and Bell at their Walker ironworks.

According to Rolt, Stephenson managed to solve the problem caused by the weight of the engine on the primitive rails. He experimented with a steam spring (to 'cushion' the weight using steam pressure acting on pistons to support the locomotive frame), but soon followed the practice of 'distributing' weight by using a number of wheels or bogies. For the Stockton and Darlington Railway

The Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) was a railway company that operated in north-east England from 1825 to 1863. The world's first public railway to use steam locomotives, its first line connected collieries near Shildon with Darli ...

Stephenson used wrought-iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" t ...

malleable rails that he had found satisfactory, notwithstanding the financial loss he suffered by not using his own patented design.

Hetton Railway

Stephenson was hired to build the 8-mile (13-km) Hetton colliery railway in 1820. He used a combination of gravity on downward inclines and locomotives for level and upward stretches. This, the first railway using no animal power, opened in 1822. This line used a gauge of which Stephenson had used before at theKillingworth

Killingworth, formerly Killingworth Township, is a town in North Tyneside, England.

Killingworth was built as a planned town in the 1960s, next to Killingworth Village, which existed for centuries before the Township. Other nearby towns an ...

wagonway.

Other locomotives include:

* 1817–1824 ''The Duke'' for the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway

The Kilmarnock and Troon Railway was an early railway line in Ayrshire, Scotland. It was constructed to bring coal from pits around Kilmarnock to coastal shipping at Troon Harbour, and passengers were carried.

It opened in 1812, and was the ...

The First Railways

Stockton and Darlington Railway

In 1821, a parliamentary bill was passed to allow the building of the

In 1821, a parliamentary bill was passed to allow the building of the Stockton and Darlington Railway

The Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) was a railway company that operated in north-east England from 1825 to 1863. The world's first public railway to use steam locomotives, its first line connected collieries near Shildon with Darli ...

(S&DR). The railway connected collieries near Bishop Auckland

Bishop Auckland () is a market town and civil parish at the confluence of the River Wear and the River Gaunless in County Durham, northern England. It is northwest of Darlington and southwest of Durham.

Much of the town's early history surr ...

to the River Tees

The River Tees (), in Northern England, rises on the eastern slope of Cross Fell in the North Pennines and flows eastwards for to reach the North Sea between Hartlepool and Redcar near Middlesbrough. The modern day history of the river has bee ...

at Stockton, passing through Darlington

Darlington is a market town in the Borough of Darlington, County Durham, England. The River Skerne flows through the town; it is a tributary of the River Tees. The Tees itself flows south of the town.

In the 19th century, Darlington underw ...

on the way. The original plan was to use horses to draw coal carts on metal rails, but after company director Edward Pease met Stephenson, he agreed to change the plans.

Stephenson surveyed the line in 1821, and assisted by his eighteen-year-old son Robert, construction began the same year.

A manufacturer was needed to provide the locomotives for the line. Pease and Stephenson had jointly established a company in Newcastle to manufacture locomotives. It was set up as

A manufacturer was needed to provide the locomotives for the line. Pease and Stephenson had jointly established a company in Newcastle to manufacture locomotives. It was set up as Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company was a locomotive manufacturing company founded in 1823 in Forth Street, Newcastle upon Tyne in England. It was the first company in the world created specifically to build railway engines.

Famous early locomoti ...

, and George's son Robert was the managing director. A fourth partner was Michael Longridge of Bedlington Ironworks. On an early trade card, Robert Stephenson & Co was described as "Engineers, Millwrights & Machinists, Brass & Iron Founders". In September 1825 the works at Forth Street, Newcastle completed the first locomotive for the railway: originally named ''Active'', it was renamed ''Locomotion

Locomotion means the act or ability of something to transport or move itself from place to place.

Locomotion may refer to:

Motion

* Motion (physics)

* Robot locomotion, of man-made devices

By environment

* Aquatic locomotion

* Flight

* Locomo ...

'' and was followed by ''Hope'', ''Diligence'' and ''Black Diamond''. The Stockton and Darlington Railway opened on 27 September 1825. Driven by Stephenson, ''Locomotion'' hauled an 80-ton load of coal and flour in two hours, reaching a speed of on one stretch. The first purpose-built passenger car, ''Experiment'', was attached and carried dignitaries on the opening journey. It was the first time passenger traffic had been run on a steam locomotive railway.

The rails used for the line were wrought-iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" t ...

, produced by John Birkinshaw

John Birkinshaw (1777-1842) was a 19th-century railway engineer from Bedlington, Northumberland noted for his invention of wrought iron rails in 1820 (patented on October 23, 1820).

Up to this point, rail systems had used either wooden rails, ...

at the Bedlington Ironworks. Wrought-iron rails could be produced in longer lengths than cast-iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

and were less liable to crack under the weight of heavy locomotives. William Losh of Walker Ironworks thought he had an agreement with Stephenson to supply cast-iron rails, and Stephenson's decision caused a permanent rift between them. The gauge Stephenson chose for the line was which subsequently was adopted as the standard gauge for railways, not only in Britain, but throughout the world.

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Stephenson had ascertained by experiments at Killingworth that half the power of the locomotive was consumed by a gradient as little as 1 in 260. He concluded that railways should be kept as level as possible. He used this knowledge while working on the

Stephenson had ascertained by experiments at Killingworth that half the power of the locomotive was consumed by a gradient as little as 1 in 260. He concluded that railways should be kept as level as possible. He used this knowledge while working on the Bolton and Leigh Railway

The Bolton and Leigh Railway (B&LR) was the first public railway in Lancashire, it opened for goods on 1 August 1828 preceding the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) by two years. Passengers were carried from 1831. The railway operated inde ...

, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was the first inter-city railway in the world. It opened on 15 September 1830 between the Lancashire towns of Liverpool and Manchester in England. It was also the first railway to rely exclusively ...

(L&MR), executing a series of difficult cuttings, embankments and stone viaducts to level their routes. Defective surveying of the original route of the L&MR caused by hostility from some affected landowners meant Stephenson encountered difficulty during Parliamentary scrutiny of the original bill, especially under cross-examination

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and ...

by Edward Hall Alderson. The bill was rejected and a revised bill for a new alignment was submitted and passed in a subsequent session. The revised alignment presented the problem of crossing Chat Moss, an apparently bottomless peat bog, which Stephenson overcame by unusual means, effectively floating the line across it. The method he used was similar to that used by John Metcalf who constructed many miles of road across marshes in the Pennines, laying a foundation of heather and branches, which became bound together by the weight of the passing coaches, with a layer of stones on top.

As the L&MR approached completion in 1829, its directors arranged a competition to decide who would build its locomotives, and the Rainhill Trials were run in October 1829. Entries could weigh no more than six tons and had to travel along the track for a total distance of . Stephenson's entry was ''Rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

'', and its performance in winning the contest made it famous. George's son Robert had been working in South America from 1824 to 1827 and returned to run the Forth Street Works while George was in Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

overseeing the construction of the line. Robert was responsible for the detailed design of ''Rocket'', although he was in constant postal communication with his father, who made many suggestions. One significant innovation, suggested by Henry Booth, treasurer of the L&MR, was the use of a fire-tube boiler

A fire-tube boiler is a type of boiler in which hot gases pass from a fire through one or more tubes running through a sealed container of water. The heat of the gases is transferred through the walls of the tubes by thermal conduction, heating ...

, invented by French engineer Marc Seguin

Marc Seguin (20 April 1786 – 24 February 1875) was a French engineer, inventor of the wire- cable suspension bridge and the multi-tubular steam-engine boiler.

Early life

Seguin was born in Annonay, Ardèche to Marc François Seguin, th ...

that gave improved heat exchange.

The opening ceremony of the L&MR, on 15 September 1830, drew luminaries from the government and industry, including the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister ...

. The day started with a procession of eight trains setting out from Liverpool. The parade was led by '' Northumbrian'' driven by George Stephenson, and included ''Phoenix'' driven by his son Robert, ''North Star'' driven by his brother Robert and ''Rocket'' driven by assistant engineer Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke FRSA (9 August 1805 – 18 September 1860) was a notable English civil engineer of the nineteenth century, particularly associated with railway projects. Locke ranked alongside Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel as on ...

. The day was marred by the death of William Huskisson

William Huskisson (11 March 177015 September 1830) was a British statesman, financier, and Member of Parliament for several constituencies, including Liverpool.

He is commonly known as the world's first widely reported railway passenger casu ...

, the Member of Parliament for Liverpool, who was struck by ''Rocket''. Stephenson evacuated the injured Huskisson to Eccles with a train, but he died from his injuries. Despite the tragedy, the railway was a resounding success. Stephenson became famous, and was offered the position of chief engineer for a wide variety of other railways.

Stephenson's skew arch bridge

1830 also saw the grand opening of the skew bridge in Rainhill over the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The bridge was the first to cross any railway at an angle. It required the structure to be constructed as two flat planes (overlapping in this case by ) between which the stonework forms a parallelogram shape when viewed from above. It has the effect of flattening the arch and the solution is to lay the bricks forming the arch at an angle to the abutments (the piers on which the arches rest). The technique, which results in a spiral effect in the arch masonry, provides extra strength in the arch to compensate for the angled abutments.

The bridge is still in use at Rainhill station, and carries traffic on the A57 (Warrington Road). The bridge is a listed structure.

1830 also saw the grand opening of the skew bridge in Rainhill over the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The bridge was the first to cross any railway at an angle. It required the structure to be constructed as two flat planes (overlapping in this case by ) between which the stonework forms a parallelogram shape when viewed from above. It has the effect of flattening the arch and the solution is to lay the bricks forming the arch at an angle to the abutments (the piers on which the arches rest). The technique, which results in a spiral effect in the arch masonry, provides extra strength in the arch to compensate for the angled abutments.

The bridge is still in use at Rainhill station, and carries traffic on the A57 (Warrington Road). The bridge is a listed structure.

Later life

Life at Alton Grange

George Stephenson moved to the parish of Alton Grange (now part of Ravenstone) in Leicestershire in 1830, originally to consult on the

George Stephenson moved to the parish of Alton Grange (now part of Ravenstone) in Leicestershire in 1830, originally to consult on the Leicester and Swannington Railway

The Leicester and Swannington Railway (L&SR) was one of England's first railways, built to bring coal from West Leicestershire collieries to Leicester, where there was great industrial demand for coal. The line opened in 1832, and included a tun ...

, a line primarily proposed to take coal from the western coal fields of the county to Leicester. The promoters of the line Mr William Stenson

William Stenson (1770–1861) was a mining engineer born in Coleorton, Leicestershire.

Background

Little is currently known about Stenson's background. Detail of his parentage remains unknown and neither is it known where he would have recei ...

and Mr John Ellis, had difficulties in raising the necessary capital as the majority of local wealth had been invested in canals. Realising the potential and need for the rail link Stephenson himself invested £2,500 and raised the remaining capital through his network of connections in Liverpool. His son Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

was made chief engineer with the first part of the line opening in 1832.

During this same period the Snibston

Snibston is an area and former civil parish east of Ravenstone, now in the parish of Ravenstone with Snibstone, in the North West Leicestershire district, in the county of Leicestershire, England. Originally rural, part of Snibston was transf ...

estate in Leicestershire came up for auction, it lay adjoining the proposed Swannington to Leicester route and was believed to contain valuable coal reserves. Stephenson realising the financial potential of the site, given its proximity to the proposed rail link and the fact that the manufacturing town of Leicester was then being supplied coal by canal from Derbyshire, bought the estate.

Employing a previously used method of mining in the midlands called tubbing to access the deep coal seams, his success could not have been greater. Stephenson's coal mine delivered the first rail cars of coal into Leicester dramatically reducing the price of coal and saving the city some £40,000 per annum.

Stephenson remained at Alton Grange until 1838 before moving to Tapton House

Tapton House, in Tapton, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, England, was once the home of engineer George Stephenson, who built the first public railway line in the world to use steam locomotives. In its time Tapton has been a gentleman's residence, a l ...

in Derbyshire.

Later career

The next ten years were the busiest of Stephenson's life as he was besieged with requests from railway promoters. Many of the first American railroad builders came to Newcastle to learn from Stephenson and the first dozen or so locomotives utilised there were purchased from the Stephenson shops. Stephenson's conservative views on the capabilities of locomotives meant he favoured circuitous routes and civil engineering that were more costly than his successors thought necessary. For example, rather than theWest Coast Main Line

The West Coast Main Line (WCML) is one of the most important railway corridors in the United Kingdom, connecting the major cities of London and Glasgow with branches to Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester and Edinburgh. It is one of the busiest ...

taking the direct route favoured by Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke FRSA (9 August 1805 – 18 September 1860) was a notable English civil engineer of the nineteenth century, particularly associated with railway projects. Locke ranked alongside Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel as on ...

over Shap between Lancaster and Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Caldew and Petteril. It is the administrative centre of the City ...

, Stephenson was in favour of a longer sea-level route via Ulverston

Ulverston is a market town and a civil parish in the South Lakeland district of Cumbria, England. In the 2001 census the parish had a population of 11,524, increasing at the 2011 census to 11,678. Historically in Lancashire, it lies a f ...

and Whitehaven

Whitehaven is a town and port on the English north west coast and near to the Lake District National Park in Cumbria, England. Historically in Cumberland, it lies by road south-west of Carlisle and to the north of Barrow-in-Furness. It i ...

. Locke's route was built.

Stephenson tended to be more casual in estimating costs and paperwork in general. He worked with Joseph Locke on the Grand Junction Railway

The Grand Junction Railway (GJR) was an early railway company in the United Kingdom, which existed between 1833 and 1846 when it was amalgamated with other railways to form the London and North Western Railway. The line built by the company w ...

with half of the line allocated to each man. Stephenson's estimates and organising ability proved inferior to those of Locke and the board's dissatisfaction led to Stephenson's resignation causing a rift between them which was never healed.

Despite Stephenson's loss of some routes to competitors due to his caution, he was offered more work than he could cope with, and was unable to accept all that was offered. He worked on the North Midland line from Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

to Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popul ...

, the York and North Midland line from Normanton to York, the Manchester and Leeds, the Birmingham and Derby, the Sheffield and Rotherham among many others.

Stephenson became a reassuring name rather than a cutting-edge technical adviser. He was the first president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 120,000 member ...

on its formation in 1847. By this time he had settled into semi-retirement, supervising his mining interests in Derbyshire – tunnelling for the North Midland Railway revealed coal seams, and Stephenson put money into their exploitation.

Personal life

George first courted Elizabeth (Betty) Hindmarsh, a farmer's daughter from Black Callerton, whom he met secretly in her orchard. Her father refused marriage because of Stephenson's lowly status as a miner. George next paid attention to Anne Henderson where he lodged with her family, but she rejected him and he transferred his attentions to her sister Frances (Fanny), who was nine years his senior. George and Fanny married atNewburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

Church on 28 November 1802. They had two children Robert (1803) and Fanny (1805) but the latter died within months. George's wife died, probably of tuberculosis, the year after. While George was working in Scotland, Robert was brought up by a succession of neighbours and then by George's unmarried sister Eleanor (Nelly), who lived with them in Killingworth on George's return.

On 29 March 1820, George (now considerably wealthier) married Betty Hindmarsh at Newburn. The marriage seems to have been happy, but there were no children and Betty died on 3 August 1845.

On 11 January 1848, at St John's Church in Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, Shropshire, George married for the third time, to Ellen Gregory, another farmer's daughter originally from Bakewell

Bakewell is a market town and civil parish in the Derbyshire Dales district of Derbyshire, England, known also for its local Bakewell pudding. It lies on the River Wye, about 13 miles (21 km) south-west of Sheffield. In the 2011 census, t ...

in Derbyshire, who had been his housekeeper. Seven months after his wedding, George contracted pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity ( pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

and died, aged 67, at noon on 12 August 1848 at Tapton House

Tapton House, in Tapton, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, England, was once the home of engineer George Stephenson, who built the first public railway line in the world to use steam locomotives. In its time Tapton has been a gentleman's residence, a l ...

in Chesterfield, Derbyshire. He was buried at Holy Trinity Church, Chesterfield, alongside his second wife.

Described by Rolt as a generous man, Stephenson financially supported the wives and families of several who had died in his employment, due to accident or misadventure, some within his family, and some not. He was also a keen gardener throughout his life; during his last years at Tapton House, he built hothouses in the estate gardens, growing exotic fruits and vegetables in a 'not too friendly' rivalry with Joseph Paxton

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, head gardener at nearby Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House is a stately home in the Derbyshire Dales, north-east of Bakewell and west of Chesterfield, England. The seat of the Duke of Devonshire, it has belonged to the Cavendish family since 1549. It stands on the east bank of the ...

, twice beating the master of the craft.

Descendants

George Stephenson had two children. His sonRobert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

was born on 16 October 1803. Robert married Frances Sanderson, daughter of a City of London professional John Sanderson, on 17 June 1829. Robert died in 1859 having no children. Robert Stephenson expanded on the work of his father and became a major railway engineer himself. Abroad, Robert was involved in the Alexandria–Cairo railway that later connected with the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

. George Stephenson's daughter was born in 1805 but died within weeks of her birth. Descendants of the wider Stephenson family continue to live in Wylam (Stephenson's birthplace) today. Also relatives connected by his marriage live in Derbyshire. Some descendants later emigrated to Perth, Australia, with later generations remaining to this day.

This Stephenson engineering family is not to be confused with the lighthouse-building engineering family of Robert Stevenson Robert Stevenson may refer to:

* Robert Stevenson (actor and politician) (1915–1975), American actor and politician

* Robert Stevenson (civil engineer) (1772–1850), Scottish lighthouse engineer

* Robert Stevenson (director) (1905–1986), Engli ...

, which was active in the same era. Note the spelling difference.

Legacy

Influence

Britain led the world in the development of railways which acted as a stimulus for theIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

by facilitating the transport of raw materials and manufactured goods. George Stephenson, with his work on the Stockton and Darlington Railway and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, paved the way for the railway engineers who followed, such as his son Robert, his assistant Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke FRSA (9 August 1805 – 18 September 1860) was a notable English civil engineer of the nineteenth century, particularly associated with railway projects. Locke ranked alongside Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel as on ...

who carried out much work on his own account and Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

. Stephenson was farsighted in realising that the individual lines being built would eventually be joined, and would need to have the same gauge. The standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), International gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge and European gauge in Europe, and SGR in E ...

used throughout much of the world is due to him. In 2002, Stephenson was named in the BBC's television show and list of the ''100 Greatest Britons

''100 Greatest Britons'' is a television series that was broadcast by the BBC in 2002. It was based on a television poll conducted to determine who the British people at that time considered the greatest Britons in history. The series included in ...

'' following a UK-wide vote, placing at no. 65.

The Victorian self-help advocate Samuel Smiles

Samuel Smiles (23 December 1812 – 16 April 1904) was a British author and government reformer. Although he campaigned on a Chartist platform, he promoted the idea that more progress would come from new attitudes than from new laws. His prim ...

had published his first biography of George Stephenson in 1857, and although attacked as biased in the favour of George at the expense his rivals as well as his son, it was popular and 250,000 copies were sold by 1904. The Band of Hope

Hope UK is a United Kingdom Christian charity based in London, England which educates children and young people about drug and alcohol abuse. Local meetings started in 1847 and a formal organisation was established in 1855 with the name The Unite ...

were selling biographies of George in 1859 at a penny a sheet, and at one point there was a suggestion to move George's body to Westminster Abbey. The centenary of George's birth was celebrated in 1881 at Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition building ...

by 15,000 people, and it was George who was featured on the reverse of the Series E five pound note

5 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

5, five or number 5 may also refer to:

* AD 5, the fifth year of the AD era

* 5 BC, the fifth year before the AD era

Literature

* ''5'' (visual novel), a 2008 visual novel by Ram

* ''5'' (comics), an awa ...

issued by the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

between 1990 and 2003. The Stephenson Railway Museum

The North Tyneside Steam Railway and Stephenson Steam Railway are visitor attractions in North Tyneside, North East England. The museum and railway workshops share a building on Middle Engine Lane adjacent to the Silverlink Retail Park. The ra ...

in North Shields

North Shields () is a town in the Borough of North Tyneside in Tyne and Wear, England. It is north-east of Newcastle upon Tyne and borders nearby Wallsend and Tynemouth.

Since 1974, it has been in the North Tyneside borough of Tyne and Wea ...

is named after George and Robert Stephenson.

Memorials

George Stephenson's Birthplace is an 18th-century

George Stephenson's Birthplace is an 18th-century historic house museum

A historic house museum is a house of historic significance that has been transformed into a museum. Historic furnishings may be displayed in a way that reflects their original placement and usage in a home. Historic house museums are held to a ...

in the village of Wylam

Wylam is a village and civil parish in the county of Northumberland. It is located about west of Newcastle upon Tyne.

It is famous for the being the birthplace of George Stephenson, one of the early railway pioneers. George Stephenson's Bir ...

, and is operated by the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

. Dial Cottage at West Moor

Forest Hall is a town in the borough of North Tyneside in the United Kingdom. It is a north eastern suburb of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle and lies six kilometres from the city centre. It borders Killingworth to the north, Holystone, Tyne and We ...

, his home from 1804, remains but the museum that once operated here is shut.

Chesterfield Museum

Chesterfield Museum and Art Gallery is a local museum and art gallery in the town of Chesterfield, Derbyshire, England.

The hall was named in honour of the British railway pioneer George Stephenson and the museum has a small collection of ...

in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, has a gallery of Stephenson memorabilia, including straight thick glass tubes he invented for growing straight cucumber

Cucumber (''Cucumis sativus'') is a widely-cultivated creeping vine plant in the Cucurbitaceae family that bears usually cylindrical fruits, which are used as culinary vegetables.Stephenson Memorial Hall

Chesterfield Museum and Art Gallery is a local museum and art gallery in the town of Chesterfield, Derbyshire, England.

The hall was named in honour of the British railway pioneer George Stephenson and the museum has a small collection of ...

not far from both Stephenson's final home at Tapton House and Holy Trinity Church within which is his vault. In Liverpool, where he lived at 34 Upper Parliament Street, a City of Liverpool Heritage Plaque is situated next to the front door.

George Stephenson College, founded in 2001 on the University of Durham's Queen's Campus in Stockton-on-Tees

Stockton-on-Tees, often simply referred to as Stockton, is a market town in the Borough of Stockton-on-Tees in County Durham, England. It is on the northern banks of the River Tees, part of the Teesside built-up area. The town had an estimat ...

, is named after him. Also named after him and his son is George Stephenson High School

George Stephenson High School is a coeducational secondary school located in Killingworth, North Tyneside, England.

History Grammar school

It was called the George Stephenson Grammar School in 1953, at which time it was built on Benton Lane (t ...

in Killingworth, Stephenson Memorial Primary School in Howdon

Howdon is a largely residential area in the eastern part of Wallsend, Tyne and Wear, England. It consists of High Howdon and the smaller settlement of East Howdon. Much of the High Howdon area was formerly called Willington prior to post-World ...

, the Stephenson Railway Museum

The North Tyneside Steam Railway and Stephenson Steam Railway are visitor attractions in North Tyneside, North East England. The museum and railway workshops share a building on Middle Engine Lane adjacent to the Silverlink Retail Park. The ra ...

in North Shields

North Shields () is a town in the Borough of North Tyneside in Tyne and Wear, England. It is north-east of Newcastle upon Tyne and borders nearby Wallsend and Tynemouth.

Since 1974, it has been in the North Tyneside borough of Tyne and Wea ...

and the Stephenson Locomotive Society. The Stephenson Centre, an SEBD Unit of Beaumont Hill School in Darlington, is named after him. His last home in Tapton, Chesterfield is now part of Chesterfield College and is called Tapton House Campus.

As a tribute to his life and works, a bronze statue of Stephenson was unveiled at Chesterfield railway station

Chesterfield railway station serves the town of Chesterfield in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the Midland Main Line. Four tracks pass through the station which has three platforms. It is currently operated by East Midlands Railway.

The stati ...

(in the town where Stephenson spent the last ten years of his life) on 28 October 2005, marking the completion of improvements to the station. At the event a full-size working replica of the ''Rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

'' was on show, which then spent two days on public display at the Chesterfield Market Festival. A statue of him dressed in classical robes stands in Neville Street, Newcastle, facing the buildings that house the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne

The Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne (or the ''Lit & Phil'' as it is popularly known) is a historical library in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, and the largest independent library outside London. The library is still av ...

and the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers

The North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers (NEIMME), commonly known as The Mining Institute, is a British Royal Chartered learned society and membership organisation dedicated to advancing science and technology in the N ...

, near Newcastle railway station

Newcastle Central Station (also known simply as Newcastle and locally as Central Station) is a major railway station in Newcastle upon Tyne. It is located on the East Coast Main Line, around north of . It is the primary national rail station ...

. The statue was sculpted in 1862 by John Graham Lough

John Graham Lough (8 January 1798 – 8 April 1876) was an English sculptor known for his funerary monuments and a variety of portrait sculpture. He also produced ideal classical male and female figures.

Life

John Graham Lough was born at Bl ...

and is listed Grade II.

From 1990 until 2003, Stephenson's portrait appeared on the reverse of Series E £5 notes

Note, notes, or NOTE may refer to:

Music and entertainment

* Musical note, a pitched sound (or a symbol for a sound) in music

* ''Notes'' (album), a 1987 album by Paul Bley and Paul Motian

* ''Notes'', a common (yet unofficial) shortened versio ...

issued by the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

. Stephenson's face is shown alongside an engraving of the ''Rocket'' steam engine and the Skerne Bridge

The Skerne Bridge is a railway bridge over the River Skerne in Darlington, County Durham. Built in 1825 for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, it carried the first train on the opening day, . It is still in use, being the oldest railway bridge ...

on the Stockton to Darlington Railway.

Stephenson's profile is carved in the facade of Lisbon's victorian railway station.

In popular culture

Stephenson was portrayed by actorGawn Grainger

Gawn Grainger (born 12 October 1937) is a British actor, playwright and screenwriter.

Early life

Some sources indicate he was born in Glasgow, Scotland on 12 October 1937. He is the son of Charles Neil Grainger and his wife Elizabeth (née Gal ...

on television in the 1985 ''Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series depicts the adventures of a Time Lord called the Doctor, an extraterrestrial being who appears to be human. The Doctor explores the ...

'' serial ''The Mark of the Rani

''The Mark of The Rani'' is the third serial of the 22nd season of the British science fiction television series ''Doctor Who'', which was first broadcast in two weekly parts on BBC1 on 2 and 9 February 1985.

The serial is set in the mining vil ...

''.

Harry Turtledove

Harry Norman Turtledove (born June 14, 1949) is an American author who is best known for his work in the genres of alternate history, historical fiction, fantasy, science fiction, and mystery fiction. He is a student of history and completed hi ...

's alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, alte ...

short story " The Iron Elephant" depicts a race between a newly invented steam engine and a mammoth-drawn train in 1782. A station master called George Stephenson features as a minor character alongside an American steam engineer called Richard Trevithick, likely indicating that they were analogous rather than historical characters.

See also

*History of Science and Technology

The history of science and technology (HST) is a field of history that examines the understanding of the natural world (science) and the ability to manipulate it ( technology) at different points in time. This academic discipline also studies the ...

* Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

* Train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and transport people or freight. Trains are typically pulled or pushed by locomotives (often ...

* Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father ...

* Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company was a locomotive manufacturing company founded in 1823 in Forth Street, Newcastle upon Tyne in England. It was the first company in the world created specifically to build railway engines.

Famous early locomoti ...

References

Biographical works

* * * * * Ruth Maxwell M.A. George Stephenson George Harrap & Company LTD., London, 1920. Heroes of All Time series.External links

Biography

Stephenson's birthplace

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stephenson, George 1781 births 1848 deaths People of the Industrial Revolution 19th-century British inventors Millwrights People from Wylam Burials in Derbyshire 19th-century British engineers English civil engineers English mechanical engineers