George Herbert Walker Bush

[Since around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; previously he was usually referred to simply as George Bush.] (June 12, 1924 – November 30, 2018) was an American politician, diplomat, and businessman who served as the 41st

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

from 1989 to 1993. A member of the

Republican Party, he previously served as the 43rd

vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

from 1981 to 1989 under President

Ronald Reagan, in the

U.S. House of Representatives, as

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, and as

Director of Central Intelligence.

Bush was raised in

Greenwich, Connecticut

Greenwich (, ) is a town in southwestern Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. At the 2020 census, the town had a total population of 63,518. The largest town on Connecticut's Gold Coast, Greenwich is home to many hedge funds and other ...

, and attended

Phillips Academy before serving in the

United States Navy Reserve

The United States Navy Reserve (USNR), known as the United States Naval Reserve from 1915 to 2005, is the Reserve Component (RC) of the United States Navy. Members of the Navy Reserve, called Reservists, are categorized as being in either the Se ...

during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. After the war, he graduated from Yale and moved to

West Texas

West Texas is a loosely defined region in the U.S. state of Texas, generally encompassing the arid and semiarid lands west of a line drawn between the cities of Wichita Falls, Abilene, and Del Rio.

No consensus exists on the boundary betwee ...

, where he established a successful oil company. After an unsuccessful run for the United States Senate, he won election to the

7th congressional district of Texas in 1966. President

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

appointed Bush to the position of

Ambassador to the United Nations

A permanent representative to the United Nations (sometimes called a "UN ambassador")"History of Ambassadors", United States Mission to the United Nations, March 2011, webpagUSUN-a. is the head of a country's diplomatic mission to the United Nati ...

in 1971 and to the position of

chairman of the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in fun ...

in 1973. In 1974, President

Gerald Ford appointed him as the

Chief of the Liaison Office to the People's Republic of China, and in 1976, Bush became the Director of Central Intelligence. Bush ran for president in 1980, but was defeated in the

Republican presidential primaries by Ronald Reagan, who then selected Bush as his vice presidential running mate.

In the

1988 presidential election, Bush defeated Democrat

Michael Dukakis, becoming the first incumbent vice president to be elected president since

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

in

1836

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Queen Maria II of Portugal marries Prince Ferdinand Augustus Francis Anthony of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

* January 5 – Davy Crockett arrives in Texas.

* January 12

** , with Charles Darwin on board, re ...

. Foreign policy drove the

Bush presidency, as he navigated the final years of the

Cold War and played a key role in the

reunification of Germany. Bush presided over the

invasion of Panama and the

Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a Coalition of the Gulf War, 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Ba'athist Iraq, ...

, ending the

Iraqi occupation of Kuwait in the latter conflict. Though the agreement was not ratified until after he left office, Bush negotiated and signed the

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which created a trade bloc consisting of the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Domestically, Bush reneged on

a 1988 campaign promise by enacting legislation to raise taxes with the justification of reducing the budget deficit. He also championed and signed three pieces of bipartisan legislation, the

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 or ADA () is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination based on disability. It affords similar protections against discrimination to Americans with disabilities as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ...

,

Immigration Act of 1990 and the

Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. He also successfully appointed

David Souter

David Hackett Souter ( ; born September 17, 1939) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1990 until his retirement in 2009. Appointed by President George H. W. Bush to fill the seat ...

and

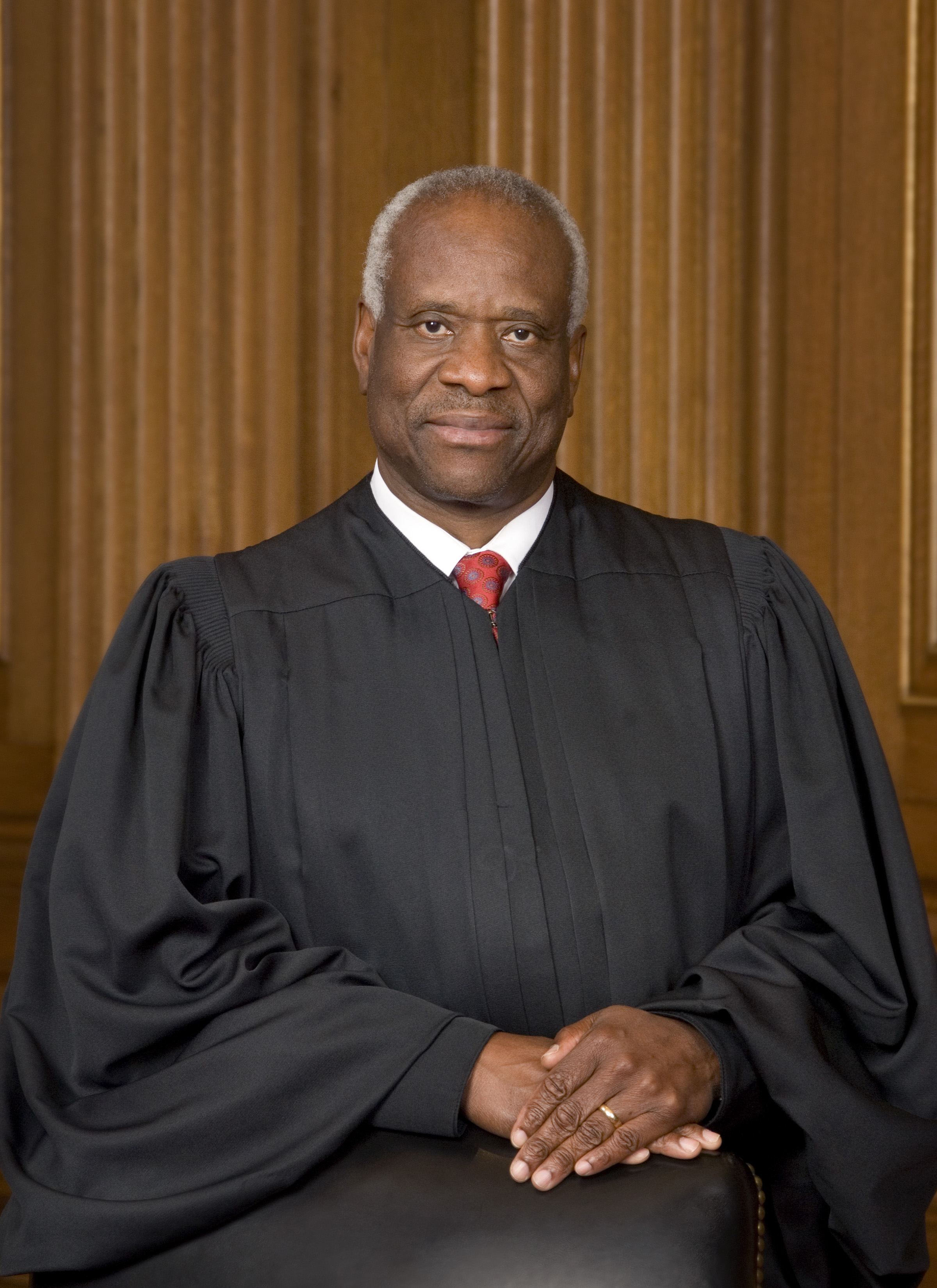

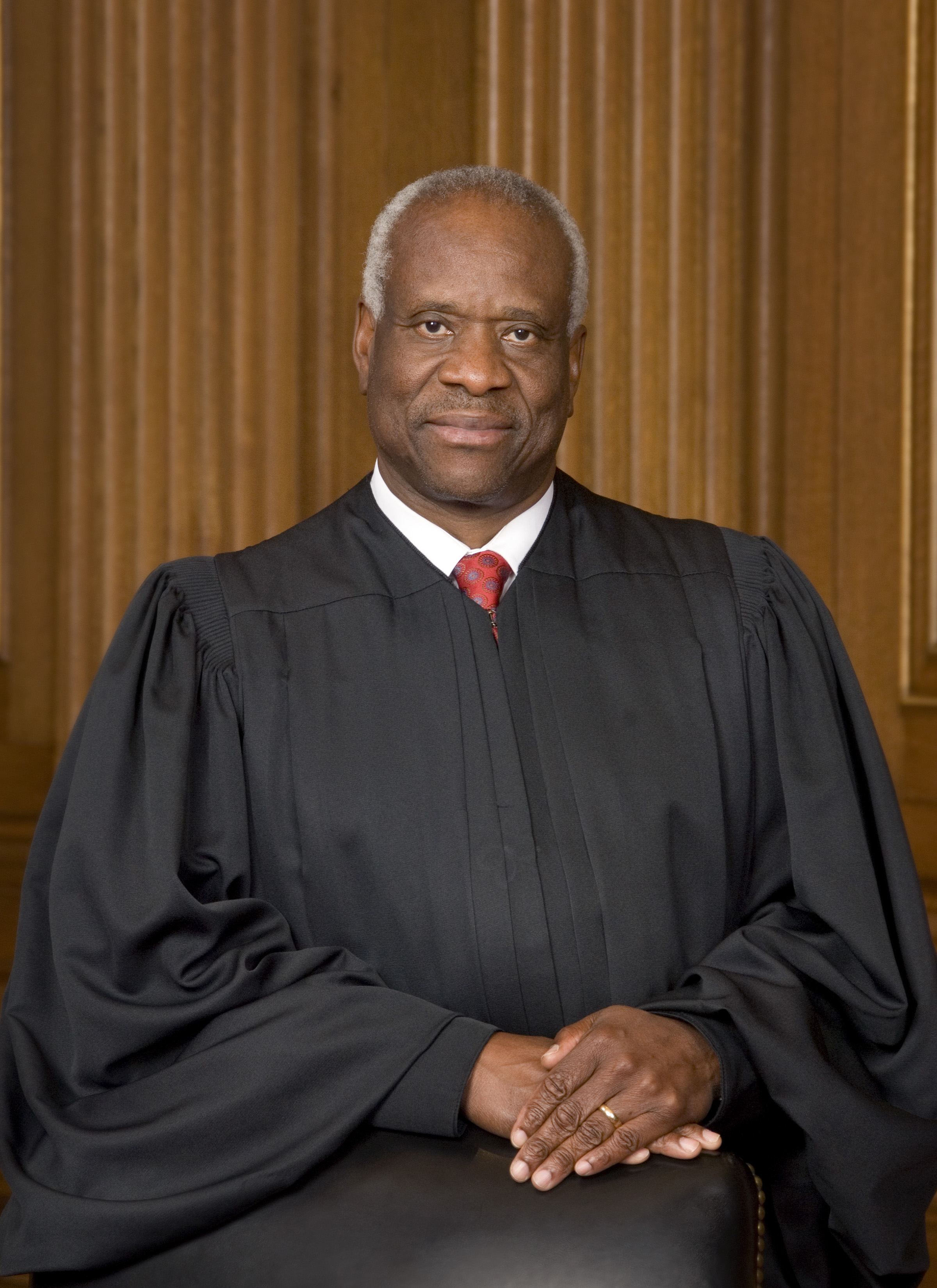

Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1 ...

to the Supreme Court. Bush lost the

1992 presidential election to Democrat

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

following an

economic recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by variou ...

, his turnaround on

his tax promise, and the decreased emphasis of foreign policy in a post–Cold War political climate.

After leaving office in 1993, Bush was active in humanitarian activities, often working alongside Clinton, his former opponent. With the victory of his son,

George W. Bush, in the

2000 presidential election, the two became the second father–son pair to serve as the nation's president, following

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

and

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

. Another son,

Jeb Bush

John Ellis "Jeb" Bush (born February 11, 1953) is an American politician and businessman who served as the 43rd governor of Florida from 1999 to 2007. Bush, who grew up in Houston, was the second son of former President George H. W. Bush ...

, unsuccessfully sought the Republican presidential nomination in the

2016 Republican primaries

Presidential primaries and caucuses of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party took place within all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories between February 1 and June 7, 2016. These elections selected ...

. Historians generally

rank

Rank is the relative position, value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level, etc. of a person or object within a ranking, such as:

Level or position in a hierarchical organization

* Academic rank

* Diplomatic rank

* Hierarchy

* ...

Bush as an above-average president.

Early life and education (1924–1948)

George Herbert Walker Bush was born in

Milton, Massachusetts

Milton is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States and an affluent suburb of Boston. The population was 28,630 at the 2020 census. Milton is the birthplace of former U.S. President George H. W. Bush, and architect Buckminster Fuller. ...

, on June 12, 1924. He was the second son of

Prescott Bush and Dorothy (Walker) Bush, and the younger brother of

Prescott Bush Jr.

The Bush family is an American dynastic family that is prominent in the fields of American politics, news, sports, entertainment, and business. They were the first family of the United States from 1989 to 1993 and again from 2001 to 2009, and w ...

His paternal grandfather,

Samuel P. Bush, worked as an executive for a railroad parts company in

Columbus, Ohio, while his maternal grandfather and namesake,

George Herbert Walker, led

Wall Street investment bank

W. A. Harriman & Co. Walker was known as "Pop", and young Bush was called "Poppy" as a tribute to him.

The Bush family moved to

Greenwich, Connecticut

Greenwich (, ) is a town in southwestern Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. At the 2020 census, the town had a total population of 63,518. The largest town on Connecticut's Gold Coast, Greenwich is home to many hedge funds and other ...

, in 1925, and Prescott took a position with W. A. Harriman & Co. (which later merged into

Brown Brothers Harriman & Co.) the following year. Bush spent most of his childhood in Greenwich, at the family vacation home in

Kennebunkport, Maine

Kennebunkport is a resort town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 3,629 people at the 2020 census. It is part of the Portland– South Portland– Biddeford metropolitan statistical area.

The town center, the are ...

, or at his maternal grandparents' plantation in South Carolina.

Because of the family's wealth, Bush was largely unaffected by the

Great Depression. He attended

Greenwich Country Day School

The Greenwich Country Day School is a co-educational, independent day school in Greenwich, Connecticut, United States, founded in 1926. As of 2019, it enrolled some 1190 students from nursery to 12th grade level. In November 2017, Greenwich Coun ...

from 1929 to 1937 and

Phillips Academy, an elite private academy in Massachusetts, from 1937 to 1942. While at Phillips Academy, he served as president of the senior class, secretary of the student council, president of the community fund-raising group, a member of the editorial board of the school newspaper, and captain of the varsity baseball and soccer teams.

File:George H W Bush at Age One and One-Half, ca 1925.gif, George H. W. Bush at his grandfather's house in Kennebunkport

Kennebunkport is a resort town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 3,629 people at the 2020 census. It is part of the Portland– South Portland–Biddeford metropolitan statistical area.

The town center, the are ...

, c. 1925

File:George H. W. Bush in 1942 Pot Pourri.jpg, Bush in Phillips Academy's 1942 yearbook

World War II

On his 18th birthday, immediately after graduating from Phillips Academy, he enlisted in the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

as a

naval aviator.

[ After a period of training, he was commissioned as an ensign in the Naval Reserve at ]Naval Air Station Corpus Christi

Naval Air Station Corpus Christi is a United States Navy naval air base located six miles (10 km) southeast of the central business district (CBD) of Corpus Christi, in Nueces County, Texas.

History

A naval air station for Corpus Christi ...

on June 9, 1943, becoming one of the youngest aviators in the Navy. Beginning in 1944, Bush served in the Pacific theater, where he flew a Grumman TBF Avenger

The Grumman TBF Avenger (designated TBM for aircraft manufactured by General Motors) is an American World War II-era torpedo bomber developed initially for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, and eventually used by several air and naval a ...

, a torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

capable of taking off from aircraft carriers. His squadron was assigned to the as a member of Air Group 51, where his lanky physique earned him the nickname "Skin".

Bush flew his first combat mission in May 1944, bombing Japanese-held Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of T ...

, and was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) on August 1, 1944. During an attack on a Japanese installation in Chichijima

, native_name_link =

, image_caption = Map of Chichijima, Anijima and Otoutojima

, image_size =

, pushpin_map = Japan complete

, pushpin_label = Chichijima

, pushpin_label_position =

, pushpin_map_alt =

, ...

, Bush's aircraft successfully attacked several targets, but was downed by enemy fire.[Meacham (2015), pp. 60–63] Several of the aviators shot down during the attack were captured and executed, and their livers were eaten by their captors. Bush's survival after such a close brush with death shaped him profoundly, leading him to ask, "Why had I been spared and what did God have for me?" He was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in the mission.

Bush returned to ''San Jacinto'' in November 1944, participating in operations in the Philippines. In early 1945, he was assigned to a new combat squadron, VT-153, where he trained to take part in an invasion of mainland Japan. Between March and May 1945 he trained in Auburn, Maine

Auburn is a city in south-central Maine within the United States. The city serves as the county seat of Androscoggin County. The population was 24,061 at the 2020 census. Auburn and its sister city Lewiston are known locally as the Twin Cities ...

where he and Barbara lived in a small apartment. On September 2, 1945, before any invasion took place, Japan formally surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Bush was released from active duty that same month, but was not formally discharged from the Navy until October 1955, at which point he had reached the rank of lieutenant.

Marriage

Bush met Barbara Pierce

Barbara Pierce Bush (June 8, 1925 – April 17, 2018) was First Lady of the United States from 1989 to 1993, as the wife of President George H. W. Bush, and the founder of the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy. She previously was ...

at a Christmas dance in Greenwich in December 1941, and, after a period of courtship, they became engaged in December 1943. While Bush was on leave from the Navy, they married in Rye, New York

Rye is a coastal suburb of New York City in Westchester County, New York, United States. It is separate from the Town of Rye, which has more land area than the city. The City of Rye, formerly the Village of Rye, was part of the Town until it r ...

, on January 6, 1945. The Bushes enjoyed a strong marriage, and Barbara would later be a popular First Lady, seen by many as "a kind of national grandmother". They had six children: George W. (b. 1946), Robin (1949–1953), Jeb (b. 1953), Neil (b. 1955), Marvin (b. 1956), and Doro (b. 1959).

College years

Bush enrolled at Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

, where he took part in an accelerated program that enabled him to graduate in two and a half years rather than the usual four.Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon (), commonly known as ''DKE'' or ''Deke'', is one of the oldest fraternities in the United States, with fifty-six active chapters and five active colonies across North America. It was founded at Yale College in 1844 by fiftee ...

fraternity and was elected its president. He also captained the Yale baseball team and played in the first two College World Series

The College World Series (CWS), officially the NCAA Men's College World Series (MCWS), is an annual baseball tournament held in June in Omaha, Nebraska. The MCWS is the culmination of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Divisi ...

as a left-handed first baseman. Like his father, he was a member of the Yale cheerleading squad and was initiated into the Skull and Bones

Skull and Bones, also known as The Order, Order 322 or The Brotherhood of Death, is an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The oldest senior class society at the university, Skull and Bone ...

secret society. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

in 1948 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics.

Business career (1948–1963)

After graduating from Yale, Bush moved his young family to

After graduating from Yale, Bush moved his young family to West Texas

West Texas is a loosely defined region in the U.S. state of Texas, generally encompassing the arid and semiarid lands west of a line drawn between the cities of Wichita Falls, Abilene, and Del Rio.

No consensus exists on the boundary betwee ...

. Biographer Jon Meacham writes that Bush's relocation to Texas allowed him to move out of the "daily shadow of his Wall Street father and Grandfather Walker, two dominant figures in the financial world", but would still allow Bush to "call on their connections if he needed to raise capital." His first position in Texas was an oil field equipment salesman for Dresser Industries

Dresser Industries was a multinational corporation headquartered in Dallas, Texas, United States, which provided a wide range of technology, products, and services used for developing energy and natural resources. In 1998, Dresser merged with its ...

, which was led by family friend Neil Mallon. While working for Dresser, Bush lived in various places with his family: Odessa, Texas

Odessa is a city in and the county seat of Ector County, Texas, United States. It is located primarily in Ector County, although a small section of the city extends into Midland County.

Odessa's population was 114,428 at the 2020 census, ma ...

; Ventura, Bakersfield and Compton, California; and Midland, Texas. In 1952, he volunteered for the successful presidential campaign of Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

. That same year, his father won election to represent Connecticut in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

as a member of the Republican Party.

With support from Mallon and Bush's uncle, George Herbert Walker Jr., Bush and John Overbey launched the Bush-Overbey Oil Development Company in 1951. In 1953 he co-founded the Zapata Petroleum Corporation

HRG Group, Inc., formerly Harbinger Group Inc. and Zapata Corporation, is a holding company based in Rochester, New York, having originated from an oil company started by a group including future U.S. president George H. W. Bush. In 2009, it w ...

, an oil company that drilled in the Permian Basin in Texas. In 1954, he was named president of the Zapata Offshore Company, a subsidiary which specialized in offshore drilling

Offshore drilling is a mechanical process where a wellbore is drilled below the seabed. It is typically carried out in order to explore for and subsequently extract petroleum that lies in rock formations beneath the seabed. Most commonly, the te ...

. Shortly after the subsidiary became independent in 1959, Bush moved the company and his family from Midland to Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 i ...

. There, he befriended James Baker

James Addison Baker III (born April 28, 1930) is an American attorney, diplomat and statesman. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 10th White House Chief of Staff and 67th United States Secretary of the Treasury under President ...

, a prominent attorney who later became an important political ally. Bush remained involved with Zapata until the mid-1960s, when he sold his stock in the company for approximately $1 million.

In 1988, ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

'' published an article alleging that Bush worked as an operative of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) during the 1960s; Bush denied this claim.

Early political career (1963–1971)

Entry into politics

By the early 1960s, Bush was widely regarded as an appealing political candidate, and some leading Democrats attempted to convince Bush to become a Democrat. He declined to leave the Republican Party, later citing his belief that the national Democratic Party favored "big, centralized government". The Democratic Party had historically dominated Texas, but Republicans scored their first major victory in the state with John G. Tower's victory in a 1961 special election to the

By the early 1960s, Bush was widely regarded as an appealing political candidate, and some leading Democrats attempted to convince Bush to become a Democrat. He declined to leave the Republican Party, later citing his belief that the national Democratic Party favored "big, centralized government". The Democratic Party had historically dominated Texas, but Republicans scored their first major victory in the state with John G. Tower's victory in a 1961 special election to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

. Motivated by Tower's victory, and hoping to prevent the far-right John Birch Society

The John Birch Society (JBS) is an American right-wing political advocacy group. Founded in 1958, it is anti-communist, supports social conservatism, and is associated with ultraconservative, radical right, far-right, or libertarian ide ...

from coming to power, Bush ran for the chairmanship of the Harris County Republican Party, winning election in February 1963. Like most other Texas Republicans, Bush supported conservative Senator Barry Goldwater over the more centrist Nelson Rockefeller in the 1964 Republican Party presidential primaries.

In 1964, Bush sought to unseat liberal Democrat Ralph W. Yarborough in Texas's U.S. Senate election.[Naftali (2007), p. 13] Bolstered by superior fundraising, Bush won the Republican primary by defeating former gubernatorial nominee Jack Cox in a run-off election

The two-round system (TRS), also known as runoff voting, second ballot, or ballotage, is a voting method used to elect a single candidate, where voters cast a single vote for their preferred candidate. It generally ensures a majoritarian resu ...

. In the general election, Bush attacked Yarborough's vote for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned racial and gender discrimination in public institutions and in many privately owned businesses. Bush argued that the act unconstitutionally expanded the powers of the federal government, but he was privately uncomfortable with the racial politics of opposing the act. He lost the election 56 percent to 44 percent, though he did run well ahead of Barry Goldwater, the Republican presidential nominee.

U.S. House of Representatives

In 1966, Bush ran for the

In 1966, Bush ran for the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

in Texas's 7th congressional district, a newly redistricted seat in the Greater Houston

Greater Houston, designated by the United States Office of Management and Budget as Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land, is the fifth-most populous metropolitan statistical area in the United States, encompassing nine counties along the Gulf Co ...

area. Initial polling showed him trailing his Democratic opponent, Harris County District Attorney Frank Briscoe, but he ultimately won the race with 57 percent of the vote. In an effort to woo potential candidates in the South and Southwest, House Republicans secured Bush an appointment to the powerful United States House Committee on Ways and Means

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other progra ...

, making Bush the first freshman to serve on the committee since 1904. His voting record in the House was generally conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

. He supported the Nixon administration

Richard Nixon's tenure as the 37th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of almost certain impeachment because of the Watergate Scanda ...

's Vietnam policies, but broke with Republicans on the issue of birth control, which he supported. He also voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1968, although it was generally unpopular in his district.1968 Republican Party presidential primaries

From March 12 to June 11, 1968, voters of the Republican Party chose its nominee for president in the 1968 United States presidential election. Former vice president Richard Nixon was selected as the nominee through a series of primary elections ...

, Bush endorsed Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, who went on to win the party's nomination. Nixon considered selecting Bush as his running mate in the 1968 presidential election, but he ultimately chose Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second vice president to resign the position, the other being John ...

instead. Bush won re-election to the House unopposed, while Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

in the presidential election. In 1970, with President Nixon's support, Bush gave up his seat in the House to run for the Senate against Yarborough. Bush easily won the Republican primary, but Yarborough was defeated by the more conservative Lloyd Bentsen in the Democratic primary. Ultimately, Bentsen defeated Bush, taking 53.5 percent of the vote.

Nixon and Ford administrations (1971–1977)

Ambassador to the United Nations

After the 1970 Senate election, Bush accepted a position as a senior adviser to the president, but he convinced Nixon to instead appoint him as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. The position represented Bush's first foray into foreign policy, as well as his first major experiences with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and China, the two major U.S. rivals in the Cold War. During Bush's tenure, the Nixon administration pursued a policy of détente, seeking to ease tensions with both the Soviet Union and China. Bush's ambassadorship was marked by a defeat on the China question, as the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

voted, in Resolution 2758, to expel the Republic of China and replace it with the People's Republic of China in October 1971. In the 1971 crisis in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, Bush supported an Indian motion at the UN General Assembly to condemn the Pakistani government of Yahya Khan

General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan , (Urdu: ; 4 February 1917 – 10 August 1980); commonly known as Yahya Khan, was a Pakistani military general who served as the third President of Pakistan and Chief Martial Law Administrator following his p ...

for waging genocide in East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Myanmar, wi ...

(modern Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

), referring to the "tradition which we have supported that the human rights question transcended domestic jurisdiction and should be freely debated". Bush's support for India at the UN put him into conflict with Nixon who was supporting Pakistan, partly because Yahya Khan

General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan , (Urdu: ; 4 February 1917 – 10 August 1980); commonly known as Yahya Khan, was a Pakistani military general who served as the third President of Pakistan and Chief Martial Law Administrator following his p ...

was a useful intermediary in his attempts to reach out to China and partly because the president was fond of Yahya Khan.

Chairman of the Republican National Committee

After Nixon won a landslide victory in the 1972 presidential election, he appointed Bush as chair of the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. Political action committee, political committee that assists the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republi ...

(RNC). In that position, he was charged with fundraising, candidate recruitment, and making appearances on behalf of the party in the media.

When Agnew was being investigated for corruption, Bush assisted, at the request of Nixon and Agnew, in pressuring John Glenn Beall Jr., the U.S. Senator from Maryland

This is a list of United States Senate, United States senators from Maryland, which ratified the United States Constitution April 28, 1788, becoming the seventh state to do so. To provide for continuity of government, the framers divided senator ...

, to force his brother, George Beall

George Beall, Jr. (February 26, 1729 – October 15, 1807) was a wealthy landowner in Maryland and Georgetown, Washington, D.C., Georgetown in what is now Washington, D.C., son of George Beall, Sr. (1695-1780) and Elizabeth Brooke (1699-1748); th ...

the U.S. Attorney in Maryland, to shutdown the investigation into Agnew. Attorney Beall ignored the pressure.

During Bush's tenure at the RNC, the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

emerged into public view; the scandal originated from the June 1972 break-in of the Democratic National Committee, but also involved later efforts to cover up the break-in by Nixon and other members of the White House. Bush initially defended Nixon steadfastly, but as Nixon's complicity became clear he focused more on defending the Republican Party.audio recording

Sound recording and reproduction is the electrical, mechanical, electronic, or digital inscription and re-creation of sound waves, such as spoken voice, singing, instrumental music, or sound effects. The two main classes of sound recording t ...

that confirmed that Nixon had plotted to use the CIA to cover up the Watergate break-in, Bush joined other party leaders in urging Nixon to resign. When Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, Bush noted in his diary that "There was an aura of sadness, like somebody died... The esignationspeech was vintage Nixon—a kick or two at the press—enormous strains. One couldn't help but look at the family and the whole thing and think of his accomplishments and then think of the shame... resident Gerald Ford's swearing-in offeredindeed a new spirit, a new lift."

Head of U.S. Liaison Office in China

Upon his ascension to the presidency, Ford strongly considered Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, and Nelson Rockefeller for the vacant position of vice president. Ford ultimately chose Nelson Rockefeller, partly because of the publication of a news report claiming that Bush's 1970 campaign had benefited from a secret fund set up by Nixon; Bush was later cleared of any suspicion by a special prosecutor. Bush accepted appointment as Chief of the U.S. Liaison Office in the People's Republic of China, making him the de facto ambassador to China. According to biographer Jon Meacham, Bush's time in China convinced him that American engagement abroad was needed to ensure global stability, and that the United States "needed to be visible but not pushy, muscular but not domineering."

Director of Central Intelligence

In January 1976, Ford brought Bush back to Washington to become the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), placing him in charge of the CIA. In the aftermath of the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

, the CIA's reputation had been damaged for its role in various covert operations, and Bush was tasked with restoring the agency's morale and public reputation.[Meacham (2015), pp. 189–193] During Bush's year in charge of the CIA, the U.S. national security apparatus actively supported Operation Condor

Operation Condor ( es, link=no, Operación Cóndor, also known as ''Plan Cóndor''; pt, Operação Condor) was a United States–backed campaign of political repression and state terror involving intelligence operations and assassination of op ...

operations and right-wing military dictatorships in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

. Meanwhile, Ford decided to drop Rockefeller from the ticket for the 1976 presidential election; he considered Bush as his running mate, but ultimately chose Bob Dole. In his capacity as DCI, Bush gave national security briefings to Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

both as a presidential candidate and as president-elect.

1980 presidential election

Bush's tenure at the CIA ended after Carter narrowly defeated Ford in the 1976 presidential election. Out of public office for the first time since the 1960s, Bush became chairman on the executive committee of the First International Bank in Houston. He also spent a year as a part-time professor of Administrative Science at Rice University's Jones School of Business, continued his membership in the Council on Foreign Relations, and joined the

Bush's tenure at the CIA ended after Carter narrowly defeated Ford in the 1976 presidential election. Out of public office for the first time since the 1960s, Bush became chairman on the executive committee of the First International Bank in Houston. He also spent a year as a part-time professor of Administrative Science at Rice University's Jones School of Business, continued his membership in the Council on Foreign Relations, and joined the Trilateral Commission

The Trilateral Commission is a nongovernmental international organization aimed at fostering closer cooperation between Japan, Western Europe and North America. It was founded in July 1973 principally by American banker and philanthropist David ...

. Meanwhile, he began to lay the groundwork for his candidacy in the 1980 Republican Party presidential primaries. In the 1980 Republican primary campaign, Bush faced Ronald Reagan, who was widely regarded as the front-runner, as well as other contenders like Senator Bob Dole, Senator Howard Baker, Texas Governor John Connally

John Bowden Connally Jr. (February 27, 1917June 15, 1993) was an American politician. He served as the 39th governor of Texas and as the 61st United States secretary of the Treasury. He began his career as a Democrat and later became a Republic ...

, Congressman Phil Crane

Philip Miller Crane (November 3, 1930 – November 8, 2014) was an American politician. He was a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 2005, representing the 8th District of Illinois in the northwestern s ...

, and Congressman John B. Anderson.

Bush's campaign cast him as a youthful, "thinking man's candidate" who would emulate the pragmatic conservatism of President Eisenhower. In the midst of the

Bush's campaign cast him as a youthful, "thinking man's candidate" who would emulate the pragmatic conservatism of President Eisenhower. In the midst of the Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen (alongside smaller groups of anti-Sovie ...

, which brought an end to a period of détente, and the Iran hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

, in which 52 Americans were taken hostage, the campaign highlighted Bush's foreign policy experience. At the outset of the race, Bush focused heavily on winning the January 21 Iowa caucuses

The Iowa caucuses are biennial electoral events for members of the Democratic and Republican parties in the U.S. state of Iowa. Unlike primary elections in most other U.S. states, where registered voters go to polling places to cast ballot ...

, making 31 visits to the state. He won a close victory in Iowa with 31.5% to Reagan's 29.4%. After the win, Bush stated that his campaign was full of momentum, or " the Big Mo", and Reagan reorganized his campaign.supply side

Supply-side economics is a Macroeconomics, macroeconomic theory that postulates economic growth can be most effectively fostered by Tax cuts, lowering taxes, Deregulation, decreasing regulation, and allowing free trade. According to supply-sid ...

-influenced plans for massive tax cuts as "voodoo economics

Reaganomics (; a portmanteau of ''Reagan'' and ''economics'' attributed to Paul Harvey), or Reaganism, refers to the neoliberal economic policies promoted by U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. These policies are commonly associat ...

". Though he favored lower taxes, Bush feared that dramatic reductions in taxation would lead to deficits and, in turn, cause inflation.

After Reagan clinched a majority of delegates in late May, Bush reluctantly dropped out of the race. At the 1980 Republican National Convention, Reagan made the last-minute decision to select Bush as his vice presidential nominee after negotiations with Ford regarding a Reagan–Ford ticket collapsed. Though Reagan had resented many of the Bush campaign's attacks during the primary campaign, and several conservative leaders had actively opposed Bush's nomination, Reagan ultimately decided that Bush's popularity with moderate Republicans made him the best and safest pick. Bush, who had believed his political career might be over following the primaries, eagerly accepted the position and threw himself into campaigning for the Reagan–Bush ticket. The 1980 general election campaign between Reagan and Carter was conducted amid a multitude of domestic concerns and the ongoing Iran hostage crisis, and Reagan sought to focus the race on Carter's handling of the economy. Though the race was widely regarded as a close contest for most of the campaign, Reagan ultimately won over the large majority of undecided voters. Reagan took 50.7 percent of the popular vote and 489 of the 538 electoral votes, while Carter won 41% of the popular vote and John Anderson, running as an independent candidate, won 6.6% of the popular vote.

After Reagan clinched a majority of delegates in late May, Bush reluctantly dropped out of the race. At the 1980 Republican National Convention, Reagan made the last-minute decision to select Bush as his vice presidential nominee after negotiations with Ford regarding a Reagan–Ford ticket collapsed. Though Reagan had resented many of the Bush campaign's attacks during the primary campaign, and several conservative leaders had actively opposed Bush's nomination, Reagan ultimately decided that Bush's popularity with moderate Republicans made him the best and safest pick. Bush, who had believed his political career might be over following the primaries, eagerly accepted the position and threw himself into campaigning for the Reagan–Bush ticket. The 1980 general election campaign between Reagan and Carter was conducted amid a multitude of domestic concerns and the ongoing Iran hostage crisis, and Reagan sought to focus the race on Carter's handling of the economy. Though the race was widely regarded as a close contest for most of the campaign, Reagan ultimately won over the large majority of undecided voters. Reagan took 50.7 percent of the popular vote and 489 of the 538 electoral votes, while Carter won 41% of the popular vote and John Anderson, running as an independent candidate, won 6.6% of the popular vote.

Vice presidency (1981–1989)

As vice president, Bush generally maintained a low profile, recognizing the constitutional limits of the office; he avoided decision-making or criticizing Reagan in any way. This approach helped him earn Reagan's trust, easing tensions left over from their earlier rivalry.

As vice president, Bush generally maintained a low profile, recognizing the constitutional limits of the office; he avoided decision-making or criticizing Reagan in any way. This approach helped him earn Reagan's trust, easing tensions left over from their earlier rivalry.James Baker

James Addison Baker III (born April 28, 1930) is an American attorney, diplomat and statesman. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 10th White House Chief of Staff and 67th United States Secretary of the Treasury under President ...

, who served as Reagan's initial chief of staff. His understanding of the vice presidency was heavily influenced by Vice President Walter Mondale, who enjoyed a strong relationship with President Carter in part because of his ability to avoid confrontations with senior staff and Cabinet members, and by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller's difficult relationship with some members of the White House staff during the Ford administration. The Bushes attended a large number of public and ceremonial events in their positions, including many state funerals, which became a common joke for comedians. As the President of the Senate, Bush also stayed in contact with members of Congress and kept the president informed on occurrences on Capitol Hill.

First term

On March 30, 1981, while Bush was in Texas, Reagan was shot and seriously wounded by John Hinckley Jr. Bush immediately flew back to Washington D.C.; when his plane landed, his aides advised him to proceed directly to the White House by helicopter in order to show that the government was still functioning.

On March 30, 1981, while Bush was in Texas, Reagan was shot and seriously wounded by John Hinckley Jr. Bush immediately flew back to Washington D.C.; when his plane landed, his aides advised him to proceed directly to the White House by helicopter in order to show that the government was still functioning.NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

allies to support the deployment of Pershing II

The Pershing II Weapon System was a solid-fueled two-stage medium-range ballistic missile designed and built by Martin Marietta to replace the Pershing 1a Field Artillery Missile System as the United States Army's primary nuclear-capable thea ...

missiles.

Reagan's approval ratings fell after his first year in office, but they bounced back when the United States began to emerge from recession in 1983. Former Vice President Walter Mondale was nominated by the Democratic Party in the 1984 presidential election. Down in the polls, Mondale selected Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro

Geraldine Anne Ferraro (August 26, 1935 March 26, 2011) was an American politician, diplomat, and attorney. She served in the United States House of Representatives from 1979 to 1985, and was the Democratic Party's vice presidential nominee ...

as his running mate in hopes of galvanizing support for his campaign, thus making Ferraro the first female major party vice presidential nominee in U.S. history. She and Bush squared off in a single televised vice presidential debate.

Second term

Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union in 1985. Rejecting the ideological rigidity of his three elderly sick predecessors, Gorbachev insisted on urgently needed economic and political reforms called " glasnost" (openness) and " perestroika" (restructuring). At the 1987 Washington Summit, Gorbachev and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty, formally the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles; / ДРСМ� ...

, which committed both signatories to the total abolition of their respective short-range and medium-range missile stockpiles. The treaty marked the beginning of a new era of trade, openness, and cooperation between the two powers. President Reagan and Secretary of State George Shultz took the lead in these negotiations, but Bush sat in on many meetings. Bush did not agree with many of the Reagan policies, but he did tell Gorbachev that he would seek to continue improving relations if he succeeded Reagan. On July 13, 1985, Bush became the first vice president to serve as acting president

An acting president is a person who temporarily fills the role of a country's president when the incumbent president is unavailable (such as by illness or a vacation) or when the post is vacant (such as for death, injury, resignation, dismissal ...

when Reagan underwent surgery to remove polyps

A polyp in zoology is one of two forms found in the phylum Cnidaria, the other being the medusa. Polyps are roughly cylindrical in shape and elongated at the axis of the vase-shaped body. In solitary polyps, the aboral (opposite to oral) end i ...

from his colon; Bush served as the acting president for approximately eight hours.

In 1986, the Reagan administration was shaken by a scandal when it was revealed that administration officials had secretly arranged weapon sales to Iran during the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Ba'athist Iraq, Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations S ...

. The officials had used the proceeds to fund the Contra

Contra may refer to:

Places

* Contra, Virginia

* Contra Costa Canal, an aqueduct in the U.S. state of California

* Contra Costa County, California

* Tenero-Contra, a municipality in the district of Locarno in the canton of Ticino in Switzerland ...

rebels in their fight against the leftist Sandinista

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto C� ...

government in Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

. Democrats had passed a law that appropriated funds could not be used to help the Contras. Instead the administration used non-appropriated funds from the sales.Lawrence Walsh

Lawrence Edward Walsh (January 8, 1912 – March 19, 2014) was an American lawyer, a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and United States Deputy Attorney General who was appoi ...

as a special prosecutor

In the United States, a special counsel (formerly called special prosecutor or independent counsel) is a lawyer appointed to investigate, and potentially prosecute, a particular case of suspected wrongdoing for which a conflict of interest exis ...

charged with investigating the Iran–Contra scandal. The investigations continued after Reagan left office and, though Bush was never charged with a crime, the Iran–Contra scandal would remain a political liability for him.

On July 3, 1988, the guided missile cruiser accidentally shot down Iran Air Flight 655, killing 290 passengers. Bush, then-vice president, defended his country at the UN by arguing that the U.S. attack had been a wartime incident and the crew of ''Vincennes'' had acted appropriately to the situation.

1988 presidential election

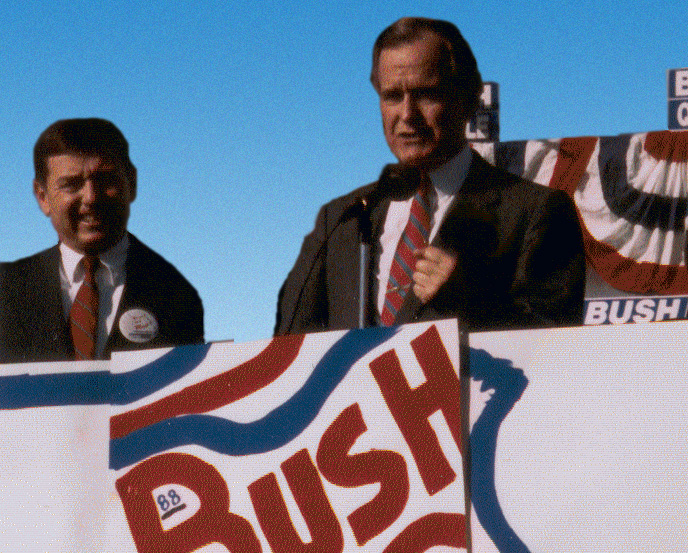

Bush began planning for a presidential run after the 1984 election, and he officially entered the

Bush began planning for a presidential run after the 1984 election, and he officially entered the 1988 Republican Party presidential primaries

From January 14 to June 14, 1988, Republican voters chose their nominee for president in the 1988 United States presidential election. Incumbent Vice President George H. W. Bush was selected as the nominee through a series of primary elections ...

in October 1987.Lee Atwater

Harvey LeRoy "Lee" Atwater (February 27, 1951 – March 29, 1991) was an American political consultant and strategist for the Republican Party. He was an adviser to US presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush and chairman of the Repub ...

, and which also included his son, George W. Bush, and media consultant Roger Ailes

Roger Eugene Ailes (May 15, 1940 – May 18, 2017) was an American television executive and media consultant. He was the chairman and CEO of Fox News, Fox Television Stations and 20th Television. Ailes was a media consultant for Republica ...

. Though he had moved to the right during his time as vice president, endorsing a Human Life Amendment

The Human Life Amendment is the name of multiple proposals to amend the United States Constitution that would have the effect of overturning the Supreme Court 1973 decision ''Roe v. Wade'', which ruled that prohibitions against abortion were uncon ...

and repudiating his earlier comments on "voodoo economics," Bush still faced opposition from many conservatives in the Republican Party. His major rivals for the Republican nomination were Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas, Congressman Jack Kemp of New York, and Christian televangelist Pat Robertson

Marion Gordon "Pat" Robertson (born March 22, 1930) is an American media mogul, religious broadcaster, political commentator, former presidential candidate, and former Southern Baptist minister. Robertson advocates a conservative Christian ...

. Reagan did not publicly endorse any candidate, but he privately expressed support for Bush.

Though considered the early front-runner for the nomination, Bush came in third in the Iowa caucus

The Iowa caucuses are biennial electoral events for members of the Democratic and Republican parties in the U.S. state of Iowa. Unlike primary elections in most other U.S. states, where registered voters go to polling places to cast ballo ...

, behind Dole and Robertson. Much as Reagan had done in 1980, Bush reorganized his staff and concentrated on the New Hampshire primary.Super Tuesday

Super Tuesday is the United States presidential primary election day in February or March when the greatest number of U.S. states hold primary elections and caucuses. Approximately one-third of all delegates to the presidential nominating co ...

, his competitors dropped out of the race.

Bush, occasionally criticized for his lack of eloquence when compared to Reagan, delivered a well-received speech at the Republican convention. Known as the "thousand points of light

The phrase "a thousand points of light" was popularized by U.S. President George H. W. Bush and later formed the name of a private, non-profit organization launched by Bush to support volunteerism.

History

The first known instance of the phras ...

" speech, it described Bush's vision of America: he endorsed the Pledge of Allegiance, prayer in schools, capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, and gun rights.Dan Quayle

James Danforth Quayle (; born February 4, 1947) is an American politician who served as the 44th vice president of the United States from 1989 to 1993 under President George H. W. Bush. A member of the Republican Party, Quayle served as a U.S. ...

of Indiana as his running mate. Though Quayle had compiled an unremarkable record in Congress, he was popular among many conservatives, and the campaign hoped that Quayle's youth would appeal to younger voters.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party nominated Governor Michael Dukakis, who was known for presiding over an economic turnaround in Massachusetts. Leading in the general election polls against Bush, Dukakis ran an ineffective, low-risk campaign. The Bush campaign attacked Dukakis as an unpatriotic liberal extremist and seized on the

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party nominated Governor Michael Dukakis, who was known for presiding over an economic turnaround in Massachusetts. Leading in the general election polls against Bush, Dukakis ran an ineffective, low-risk campaign. The Bush campaign attacked Dukakis as an unpatriotic liberal extremist and seized on the Willie Horton

William R. Horton (born August 12, 1951), commonly referred to as "Willie Horton", is an American convicted felon who became notorious for committing violent crimes while on furlough from prison, where he was serving a life sentence without the ...

case, in which a convicted felon from Massachusetts raped a woman while on a prison furlough, a program Dukakis supported as governor. The Bush campaign charged that Dukakis presided over a " revolving door" that allowed dangerous convicted felons to leave prison. Dukakis damaged his own campaign with a widely mocked ride in an M1 Abrams tank and a poor performance at the second presidential debate. Bush also attacked Dukakis for opposing a law that would require all students to recite the Pledge of Allegiance.Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

in 1836

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Queen Maria II of Portugal marries Prince Ferdinand Augustus Francis Anthony of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

* January 5 – Davy Crockett arrives in Texas.

* January 12

** , with Charles Darwin on board, re ...

and the first person to succeed a president from his own party via election since Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

in 1929

This year marked the end of a period known in American history as the Roaring Twenties after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in a worldwide Great Depression. In the Americas, an agreement was brokered to end the Cristero War, a Catholic ...

.

Presidency (1989–1993)

Bush was

Bush was inaugurated

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugur ...

on January 20, 1989, succeeding Ronald Reagan. In his inaugural address, Bush said:

Bush's first major appointment was that of James Baker

James Addison Baker III (born April 28, 1930) is an American attorney, diplomat and statesman. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 10th White House Chief of Staff and 67th United States Secretary of the Treasury under President ...

as Secretary of State.[Greene (2015), pp. 53–55] Leadership of the Department of Defense went to Dick Cheney, who had previously served as Gerald Ford's chief of staff and would later serve as vice president under his son George W. Bush. Jack Kemp joined the administration as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, while Elizabeth Dole

Mary Elizabeth Alexander Hanford Dole (née Hanford; born July 29, 1936)Mary Ella Cathey Hanford, "Asbury and Hanford Families: Newly Discovered Genealogical Information" ''The Historical Trail'' 33 (1996), pp. 44–45, 49. is an American attorn ...

, the wife of Bob Dole and a former Secretary of Transportation, became the Secretary of Labor under Bush. Bush retained several Reagan officials, including Secretary of the Treasury Nicholas F. Brady, Attorney General Dick Thornburgh, and Secretary of Education Lauro Cavazos. New Hampshire Governor John Sununu, a strong supporter of Bush during the 1988 campaign, became chief of staff.

Foreign affairs

End of the Cold War

During the first year of his tenure, Bush put a pause on Reagan's détente policy toward the USSR. Bush and his advisers were initially divided on Gorbachev; some administration officials saw him as a democratic reformer, but others suspected him of trying to make the minimum changes necessary to restore the Soviet Union to a competitive position with the United States. In 1989, all the Communist governments collapsed in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev declined to send in the Soviet military, effectively abandoning the

During the first year of his tenure, Bush put a pause on Reagan's détente policy toward the USSR. Bush and his advisers were initially divided on Gorbachev; some administration officials saw him as a democratic reformer, but others suspected him of trying to make the minimum changes necessary to restore the Soviet Union to a competitive position with the United States. In 1989, all the Communist governments collapsed in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev declined to send in the Soviet military, effectively abandoning the Brezhnev Doctrine

The Brezhnev Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy that proclaimed any threat to socialist rule in any state of the Soviet Bloc in Central and Eastern Europe was a threat to them all, and therefore justified the intervention of fellow socialist st ...

. The U.S. was not directly involved in these upheavals, but the Bush administration avoided gloating over the demise of the Eastern Bloc to avoid undermining further democratic reforms.[Herring (2008), pp. 904–906]

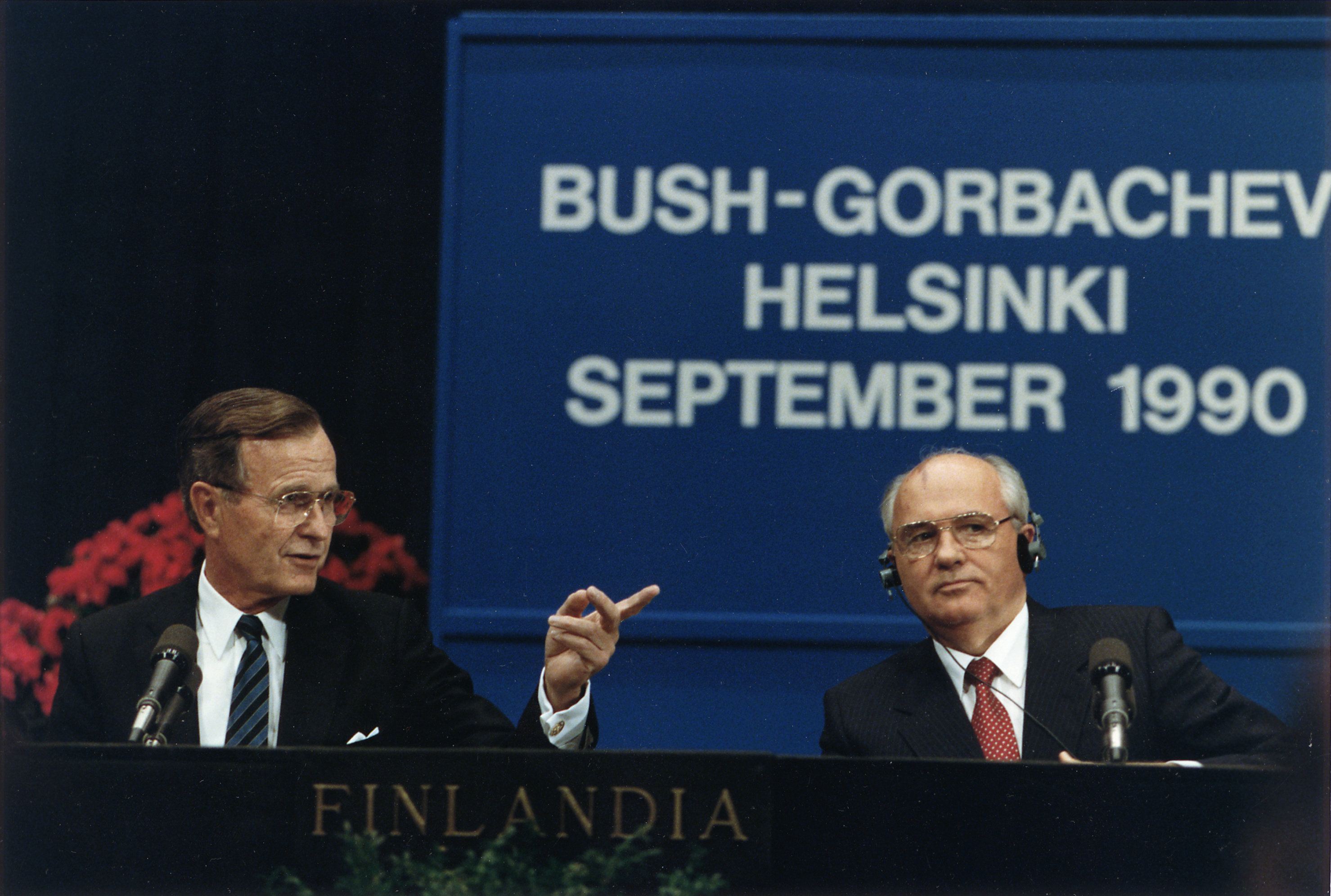

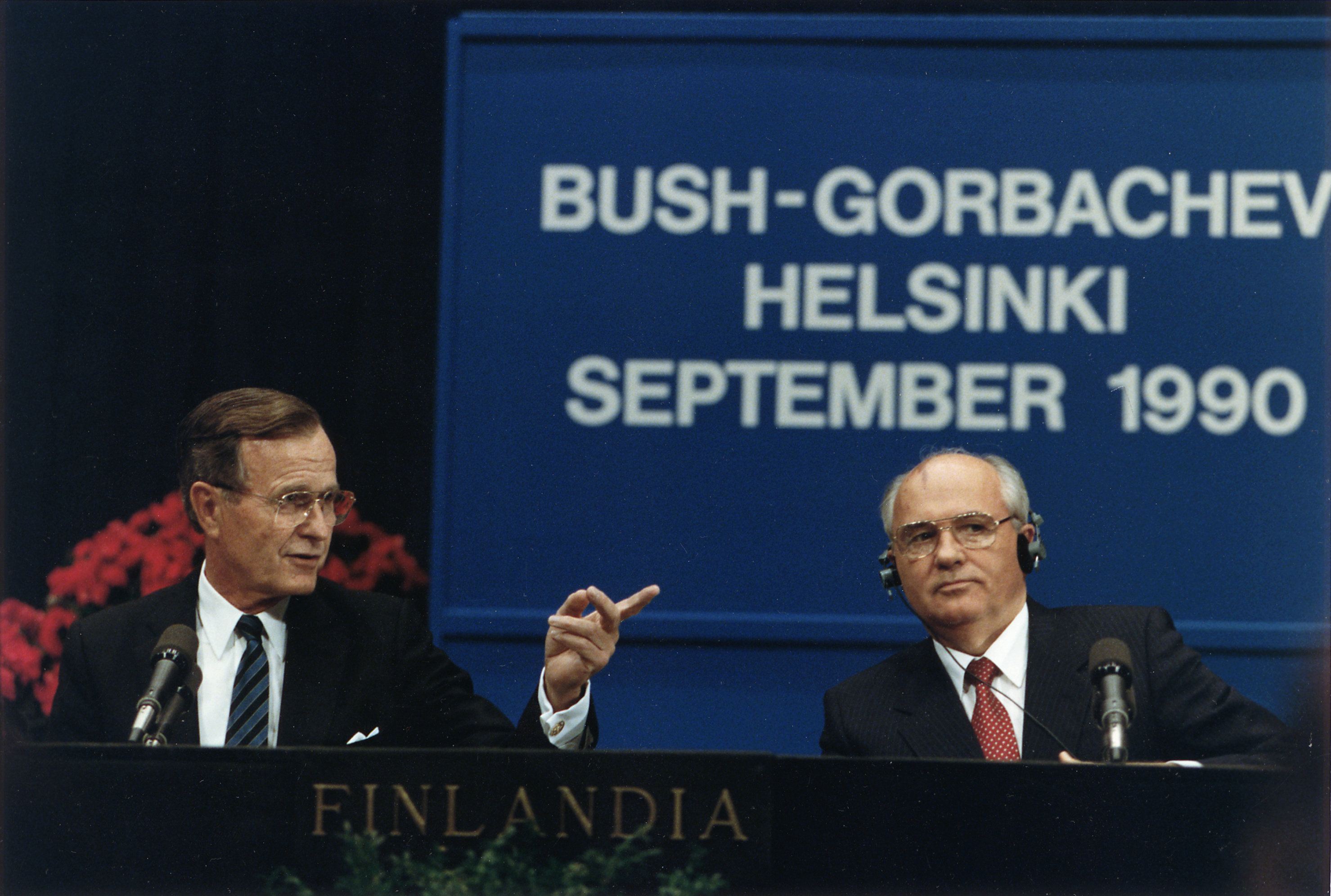

Bush and Gorbachev met at the Malta Summit in December 1989. Though many on the right remained wary of Gorbachev, Bush came away with the belief that Gorbachev would negotiate in good faith. For the remainder of his term, Bush sought cooperative relations with Gorbachev, believing that he was the key to peace. The primary issue at the Malta Summit was the potential reunification of Germany. While Britain and France were wary of a re-unified Germany, Bush joined West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (; 3 April 1930 – 16 June 2017) was a German politician who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998 and Leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998. Kohl's 16-year tenure is the longes ...

in pushing for German reunification. Gorbachev used force to suppress nationalist movements within the Soviet Union itself. A crisis in Lithuania left Bush in a difficult position, as he needed Gorbachev's cooperation in the reunification of Germany and feared that the collapse of the Soviet Union could leave nuclear arms in dangerous hands. The Bush administration mildly protested Gorbachev's suppression of Lithuania's independence movement, but took no action to directly intervene. Bush warned independence movements of the disorder that could come with secession from the Soviet Union; in a 1991 address that critics labeled the " Chicken Kiev speech", he cautioned against "suicidal nationalism". In July 1991, Bush and Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) treaty, in which both countries agreed to cut their strategic nuclear weapons by 30 percent.

Gorbachev used force to suppress nationalist movements within the Soviet Union itself. A crisis in Lithuania left Bush in a difficult position, as he needed Gorbachev's cooperation in the reunification of Germany and feared that the collapse of the Soviet Union could leave nuclear arms in dangerous hands. The Bush administration mildly protested Gorbachev's suppression of Lithuania's independence movement, but took no action to directly intervene. Bush warned independence movements of the disorder that could come with secession from the Soviet Union; in a 1991 address that critics labeled the " Chicken Kiev speech", he cautioned against "suicidal nationalism". In July 1991, Bush and Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) treaty, in which both countries agreed to cut their strategic nuclear weapons by 30 percent.

In August 1991, hard-line Communists launched a coup against Gorbachev; while the coup quickly fell apart, it broke the remaining power of Gorbachev and the central Soviet government. Later that month, Gorbachev resigned as general secretary of the Communist party, and Russian president

In August 1991, hard-line Communists launched a coup against Gorbachev; while the coup quickly fell apart, it broke the remaining power of Gorbachev and the central Soviet government. Later that month, Gorbachev resigned as general secretary of the Communist party, and Russian president Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

ordered the seizure of Soviet property. Gorbachev clung to power as the President of the Soviet Union

The president of the Soviet Union (russian: Президент Советского Союза, Prezident Sovetskogo Soyuza), officially the president of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (), abbreviated as president of the USSR (), was ...

until December 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved. Fifteen states emerged from the Soviet Union, and of those states, Russia was the largest and most populous. Bush and Yeltsin met in February 1992, declaring a new era of "friendship and partnership".

Invasion of Panama

Through the late 1980s, the U.S. provided aid to Manuel Noriega

Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno (; February 11, 1934 – May 29, 2017) was a Panamanian dictator, politician and military officer who was the ''de facto'' ruler of Panama from 1983 to 1989. An authoritarian ruler who amassed a personal f ...

, the anti-Communist leader of Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

. Noriega had long standing ties to United States intelligence agencies, including during Bush's tenure as Director of Central Intelligence, and was also deeply involved in drug trafficking. In May 1989, Noriega annulled the results of a democratic presidential election in which Guillermo Endara had been elected. Bush objected to the annulment of the election and worried about the status of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

with Noriega still in office.[Patterson (2005), pp. 226–227] Bush dispatched 2,000 soldiers to the country, where they began conducting regular military exercises in violation of prior treaties.United States invasion of Panama

The United States invasion of Panama, codenamed Operation Just Cause, lasted over a month between mid-December 1989 and late January 1990. It occurred during the administration of President George H. W. Bush and ten years after the Torrijos� ...

, known as "Operation Just Cause". The invasion was the first large-scale American military operation in more than 40 years that was not related to the Cold War. American forces quickly took control of the Panama Canal Zone and Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

. Noriega surrendered on January 3, 1990, and was quickly transported to a prison in the United States. Twenty-three Americans died in the operation, while another 394 were wounded. Noriega was convicted and imprisoned on racketeering and drug trafficking charges in April 1992.Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

or the threat of Communism, but rather on the grounds that it was in the best interests of the United States.

Gulf War

Faced with massive debts and low oil prices in the aftermath of the

Faced with massive debts and low oil prices in the aftermath of the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Ba'athist Iraq, Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations S ...

, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

decided to conquer the country of Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

, a small, oil-rich country situated on Iraq's southern border. After Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, Bush imposed economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they ma ...

on Iraq and assembled a multi-national coalition opposed to the invasion.[Patterson (2005), pp. 230–232] The administration feared that a failure to respond to the invasion would embolden Hussein to attack Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

or Israel, and wanted to discourage other countries from similar aggression. Bush also wanted to ensure continued access to oil, as Iraq and Kuwait collectively accounted for 20 percent of the world's oil production, and Saudi Arabia produced another 26 percent of the world's oil supply.

At Bush's insistence, in November 1990, the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

approved a resolution authorizing the use of force if Iraq did not withdraw from Kuwait by January 15, 1991. Gorbachev's support, as well as China's abstention, helped ensure passage of the UN resolution. Bush convinced Britain, France, and other nations to commit soldiers to an operation against Iraq, and he won important financial backing from Germany, Japan, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at t ...

. In January 1991, Bush asked Congress to approve a joint resolution authorizing a war against Iraq.[Patterson (2005), pp. 232–233] Bush believed that the UN resolution had already provided him with the necessary authorization to launch a military operation against Iraq, but he wanted to show that the nation was united behind a military action. Despite the opposition of a majority of Democrats in both the House and the Senate, Congress approved the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 1991.peacekeeping force

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United N ...

in a demilitarized zone between Kuwait and Iraq. A March 1991 Gallup poll showed that Bush had an approval rating of 89 percent, the highest presidential approval rating in the history of Gallup polling. After 1991, the UN maintained economic sanctions against Iraq, and the United Nations Special Commission

United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) was an inspection regime created by the United Nations to ensure Iraq's compliance with policies concerning Iraqi production and use of weapons of mass destruction after the Gulf War. Between 1991 and 199 ...

was assigned to ensure that Iraq did not revive its weapons of mass destruction program.

NAFTA

In 1987, the U.S. and Canada had reached a free trade agreement that eliminated many tariffs between the two countries. President Reagan had intended it as the first step towards a larger trade agreement to eliminate most tariffs among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The Bush administration, along with the Progressive Conservative Canadian Prime Minister

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the confidence of a majority the elected House of Commons; as such ...

Brian Mulroney, spearheaded the negotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Mexico. In addition to lowering tariffs, the proposed treaty would affect patents, copyrights, and trademarks.fast track

The fast track is an informal English term meaning "the quickest and most direct route to achievement of a goal, as in competing for professional advancement". By definition, it implies that a less direct, slower route also exists.

Fast track or F ...

authority, which grants the president the power to submit an international trade agreement to Congress without the possibility of amendment. Despite congressional opposition led by House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt, both houses of Congress voted to grant Bush fast track authority. NAFTA was signed in December 1992, after Bush lost re-election, but President Clinton won ratification of NAFTA in 1993. NAFTA remains controversial for its impact on wages, jobs, and overall economic growth.

Domestic affairs

Economy and fiscal issues

The U.S. economy had generally performed well since emerging from recession in late 1982, but it slipped into a mild recession in 1990. The unemployment rate rose from 5.9 percent in 1989 to a high of 7.8 percent in mid-1991.[Blue-collar Towns Have Highest Jobless Numbers](_blank)

, ''Hartford Courant'' onnecticut W. Joseph Campbell, September 1, 1991. Large federal deficits, spawned during the Reagan years, rose from $152.1 billion in 1989 to $220 billion for 1990;fiscal year

A fiscal year (or financial year, or sometimes budget year) is used in government accounting, which varies between countries, and for budget purposes. It is also used for financial reporting by businesses and other organizations. Laws in many ...