General Yamashita on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a

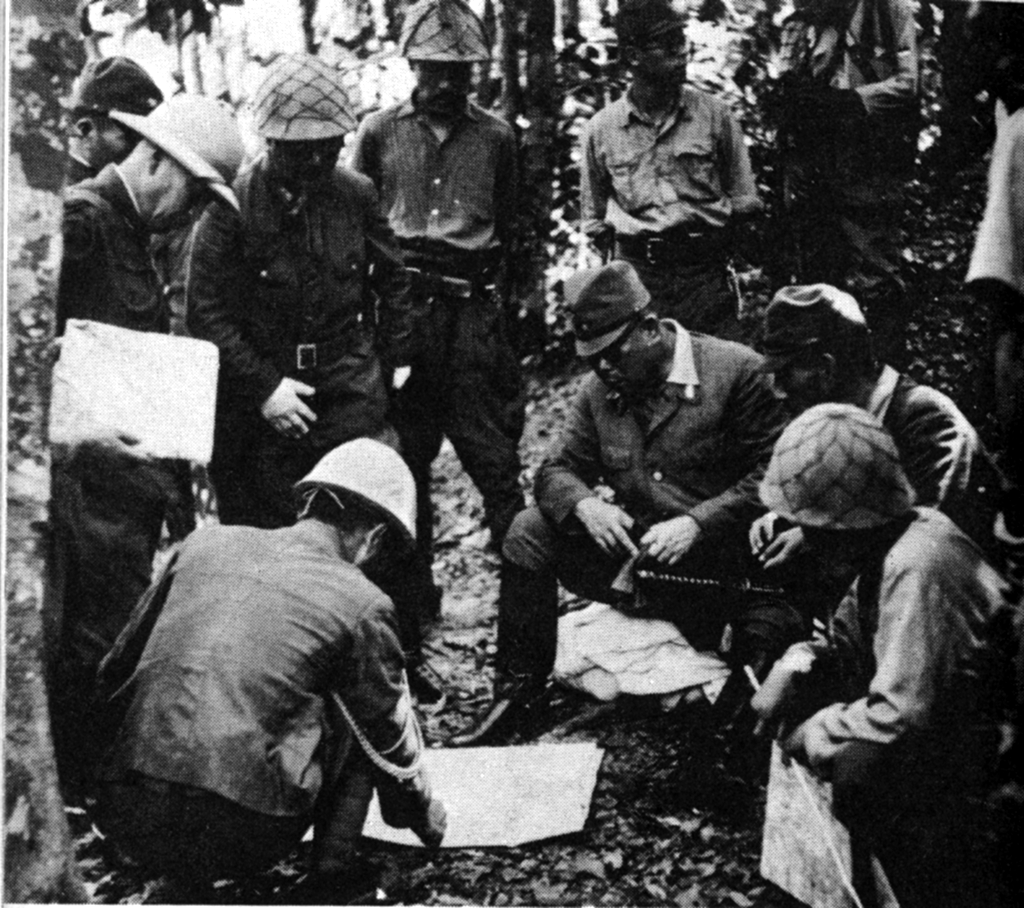

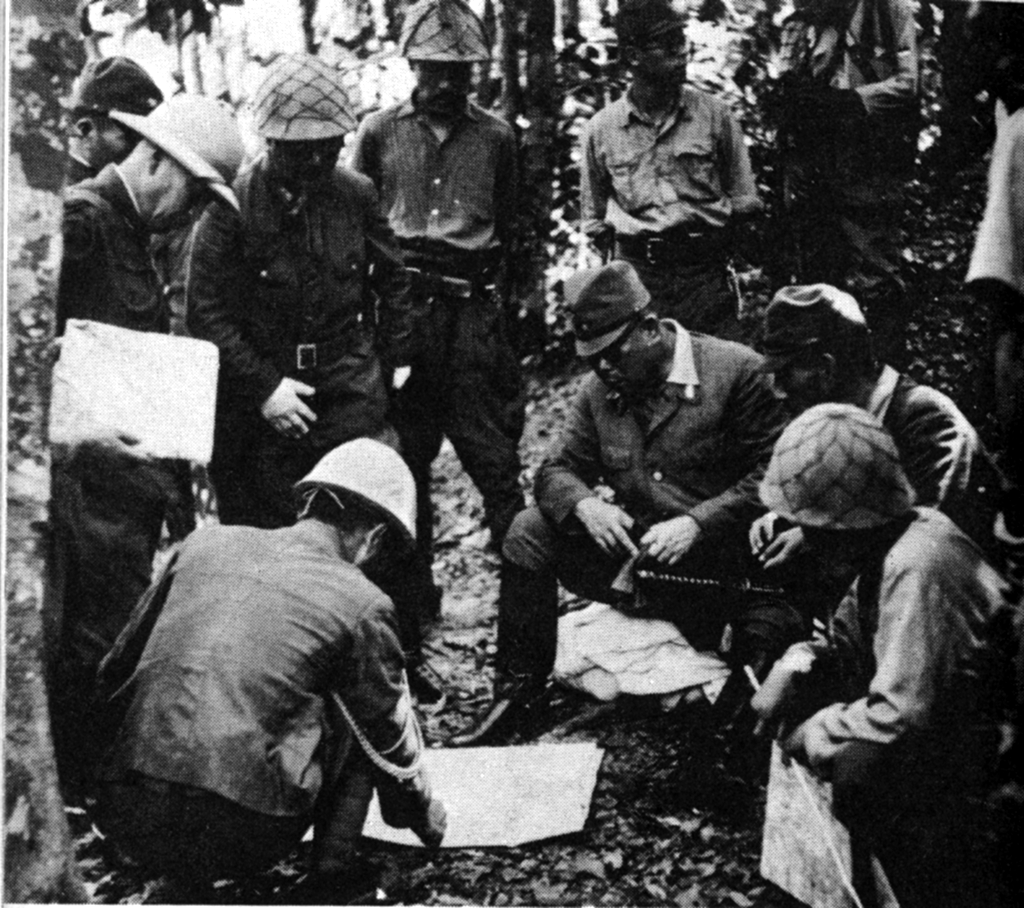

On 6 November 1941 Lt. Gen. Yamashita was put in command of the Twenty-Fifth Army. It was his belief that victory in Malaya would be successful only if his troops could make an amphibious landing—something that was dependent on whether he would have enough air and naval support to provide a good landing site.

On 8 December he launched an

On 6 November 1941 Lt. Gen. Yamashita was put in command of the Twenty-Fifth Army. It was his belief that victory in Malaya would be successful only if his troops could make an amphibious landing—something that was dependent on whether he would have enough air and naval support to provide a good landing site.

On 8 December he launched an

On 26 September 1944, when the war situation was critical for Japan, Yamashita was rescued from his enforced exile in China by the new Japanese government after the downfall of Hideki Tōjō and his cabinet, and he assumed the command of the Fourteenth Area Army to defend the occupied Philippines on 10 October. U.S. forces landed on

On 26 September 1944, when the war situation was critical for Japan, Yamashita was rescued from his enforced exile in China by the new Japanese government after the downfall of Hideki Tōjō and his cabinet, and he assumed the command of the Fourteenth Area Army to defend the occupied Philippines on 10 October. U.S. forces landed on

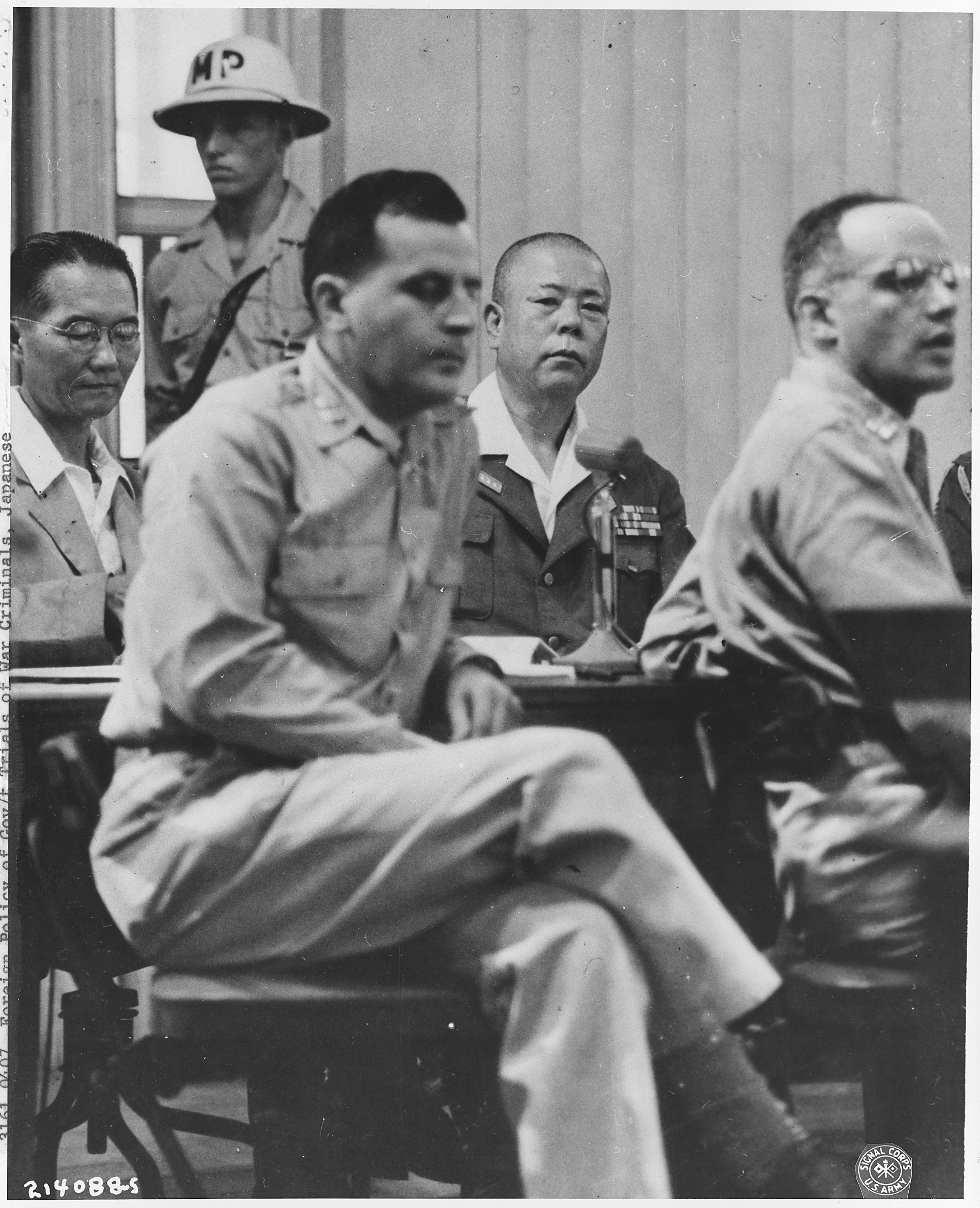

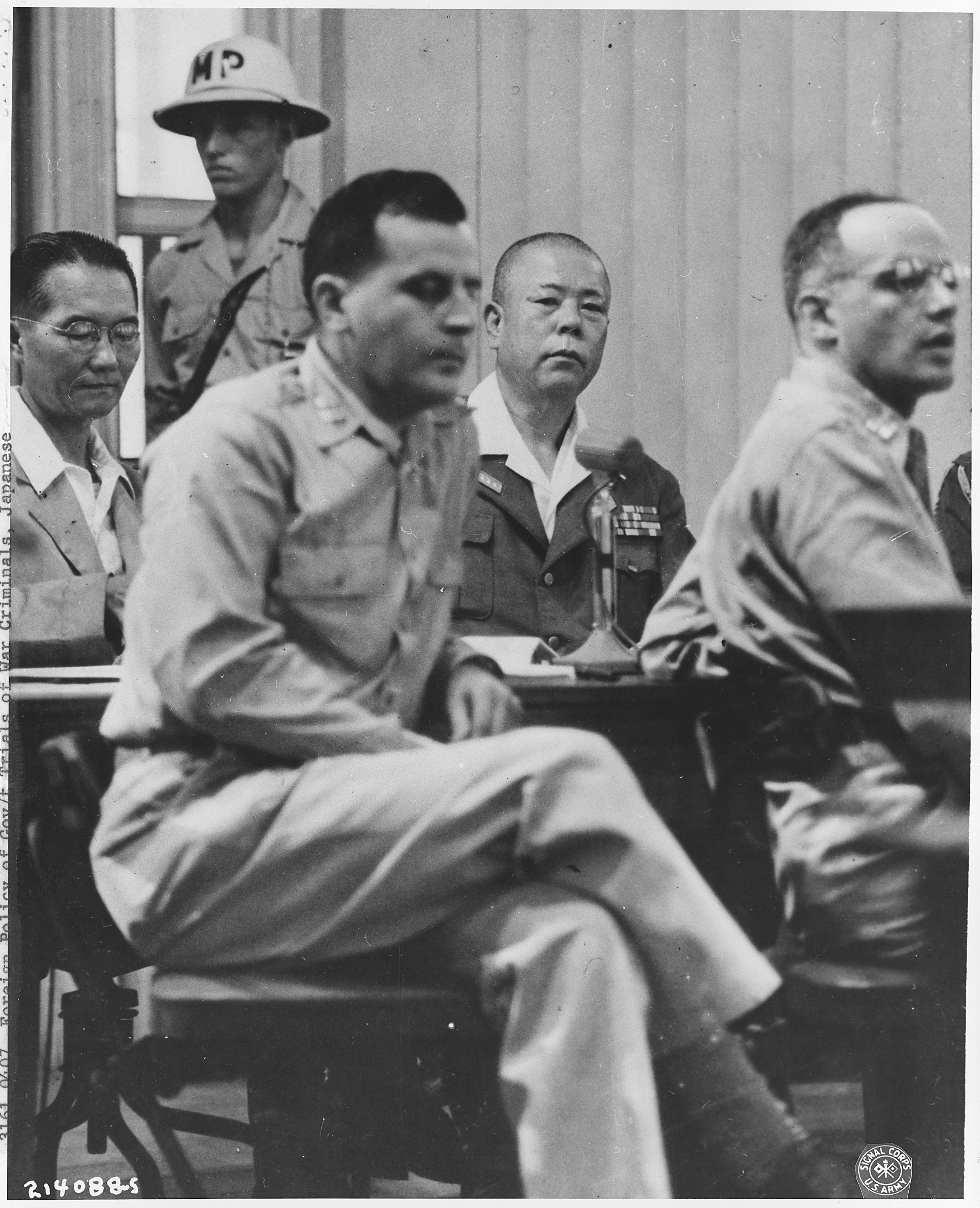

From 29 October to 7 December 1945, an American

From 29 October to 7 December 1945, an American  For his part Yamashita denied he had knowledge of the crimes committed by his men, and claimed that he would have harshly punished them if he had had that knowledge. Further, he argued that with an army as large as his, there was no way for him to control all actions by all his subordinates. As such he felt what he was really being charged with was losing the war:

The court found Yamashita guilty as charged and sentenced him to death. Clarke appealed the sentence to General MacArthur, who upheld it. He then appealed to the Supreme Court of the Philippines and the Supreme Court of the United States, both of which declined to review the verdict. President Truman denied Yamashita's petition to grant clemency and let the decision stand.

In dissent from the Supreme Court of the United States's majority, Justice W.B. Rutledge wrote:

The legitimacy of the hasty trial was questioned at the time, including by Justice

For his part Yamashita denied he had knowledge of the crimes committed by his men, and claimed that he would have harshly punished them if he had had that knowledge. Further, he argued that with an army as large as his, there was no way for him to control all actions by all his subordinates. As such he felt what he was really being charged with was losing the war:

The court found Yamashita guilty as charged and sentenced him to death. Clarke appealed the sentence to General MacArthur, who upheld it. He then appealed to the Supreme Court of the Philippines and the Supreme Court of the United States, both of which declined to review the verdict. President Truman denied Yamashita's petition to grant clemency and let the decision stand.

In dissent from the Supreme Court of the United States's majority, Justice W.B. Rutledge wrote:

The legitimacy of the hasty trial was questioned at the time, including by Justice  Former war crimes prosecutor Allan A. Ryan has argued that by order of General MacArthur and five other generals, and the Supreme Court of the United States, Yamashita was executed for what his soldiers did without his approval or even prior knowledge. The two dissenting Supreme Court Justices called the entire trial a miscarriage of justice, an exercise in vengeance, and a denial of human rights.

Former war crimes prosecutor Allan A. Ryan has argued that by order of General MacArthur and five other generals, and the Supreme Court of the United States, Yamashita was executed for what his soldiers did without his approval or even prior knowledge. The two dissenting Supreme Court Justices called the entire trial a miscarriage of justice, an exercise in vengeance, and a denial of human rights.

CASE NO. 21; TRIAL OF GENERAL TOMOYUKI YAMASHITA; UNITED STATES MILITARY COMMISSION, MANILA, (8TH OCTOBER-7TH DECEMBER, 1945), AND THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES (JUDGMENTS DELIVERED ON 4TH FEBRUARY, 1946)

'. Source: Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals. Selected and Prepared by the United Nations War Crimes Commission. Volume IV. London: HMSO, 1948. Document compiled by Dr S D Stein, Faculty of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences

WW2DB: Tomoyuki Yamashita

with

private collection of photographs of Yamashita

Last Words of the Tiger of Malaya, General Yamashita Tomoyuki

by Yuki Tanaka, research professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute (Tanaka's commentary is followed by the full text of Yamashita's statement). * Laurie Barber,

from Issue 2, Volume 1, September 1998

' within the History Department at the

The George Mountz Collection of Yamashita Trial Photographs

(111 photographs)

Japanese Press translation on the trial of General Yamashita 1945

from the Dartmouth Library Digital Collections * {{DEFAULTSORT:Yamashita, Tomoyuki 1885 births 1946 deaths People from Kōchi Prefecture 20th-century executions by the United States military Executed military leaders Imperial Japanese Army generals of World War II Japanese military attachés Japanese generals Japanese people convicted of war crimes Japanese people executed abroad Executed Japanese people People executed by the United States military by hanging Military history of Malaya during World War II People executed for war crimes Japanese occupation of Singapore Imperial Japanese Army officers Grand Cordons of the Order of the Rising Sun Recipients of the Order of the Golden Kite Japanese mass murderers Executed mass murderers

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

officer and convicted war criminal, who was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Yamashita led Japanese forces during the invasion of Malaya

The Malayan campaign, referred to by Japanese sources as the , was a military campaign fought by Allied and Axis forces in Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 15 February 1942 during the Second World War. It was dominated by land battles betwee ...

and Battle of Singapore

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire of ...

, with his accomplishment of conquering Malaya and Singapore in 70 days earning him the sobriquet "The Tiger of Malaya" and led to the British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

calling the ignominious fall of Singapore to Japan the "worst disaster" and "largest capitulation" in British military history.

Yamashita was assigned to defend the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

from the advancing Allied forces later in the war, and while unable to prevent the Allied advance, he was able to hold on to part of Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, as ...

until after the formal Surrender of Japan in August 1945.

After the war, Yamashita was tried for war crimes committed by troops under his command during the Japanese defense of the occupied Philippines in 1944. Yamashita denied ordering those war crimes and denied having knowledge that they even occurred. Conflicting evidence was presented during the trial concerning whether Yamashita had implicitly affirmed commission of these crimes in his orders and whether he knew of the crimes being committed. The court eventually found Yamashita guilty and he was executed in 1946. The ruling against Yamashita – holding the commander responsible for subordinates' war crimes as long as the commander did not attempt to discover and stop them from occurring – came to be known as the Yamashita standard.

Biography

Yamashita was the second son of a local doctor in Osugi, a village in what is now part of Ōtoyo,Kōchi Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located on the island of Shikoku. Kōchi Prefecture has a population of 757,914 (1 December 2011) and has a geographic area of 7,103 km2 (2,742 sq mi). Kōchi Prefecture borders Ehime Prefecture to the northwest and ...

, Shikoku

is the smallest of the four main islands of Japan. It is long and between wide. It has a population of 3.8 million (, 3.1%). It is south of Honshu and northeast of Kyushu. Shikoku's ancient names include ''Iyo-no-futana-shima'' (), '' ...

. He attended military preparatory schools in his youth.

Early military career

In November 1905, Yamashita graduated from the 18th class of theImperial Japanese Army Academy

The was the principal officer's training school for the Imperial Japanese Army. The programme consisted of a junior course for graduates of local army cadet schools and for those who had completed four years of middle school, and a senior course f ...

. He was ranked 16th out of 920 cadets. In December 1908 he was promoted to lieutenant and fought against the German Empire in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in Shandong, China in 1914. In May 1916 he was promoted to captain. He attended the 28th class of the Army War College, graduating sixth in his class in 1916. The same year, he married Hisako Nagayama, daughter of retired Gen. Nagayama. Yamashita became an expert on Germany, serving as assistant military attaché at Bern and Berlin from 1919 to 1922.

In February 1922, he was promoted to major. He twice served in the Military Affairs Bureau of the War Ministry responsible for the Ugaki Army Reduction Program, aimed at reforming the Japanese army by streamlining its organisation despite facing fierce opposition from factions within the Army.

In 1922, upon his return to Japan, Major Yamashita served in the Imperial Headquarters and the Staff College, receiving promotion to lieutenant-colonel in August 1925. While posted to the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff

The , also called the Army General Staff, was one of the two principal agencies charged with overseeing the Imperial Japanese Army.

Role

The was created in April 1872, along with the Navy Ministry, to replace the Ministry of Military Affairs ...

, Yamashita unsuccessfully promoted a military reduction plan. Despite his ability, Yamashita fell into disfavor as a result of his involvement with political factions within the Japanese military.

As a leading member of the "Imperial Way" group, he became a rival to Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

and other members of the "Control Faction". In 1927 Yamashita was posted to Vienna, Austria, as a military attaché until 1930. He was then promoted to the rank of colonel. In 1930 Col. Yamashita was given command of the elite 3rd Imperial Infantry Regiment. (Imperial Guards Division). He was promoted to major-general in August 1934.

After the February 26 Incident of 1936, he fell into disfavor with Emperor Hirohito due to his appeal for leniency toward rebel officers involved in the attempted coup. He realized that he had lost the trust of the Emperor and decided to resign from the Army—a decision that his superiors dissuaded him from carrying out. He was eventually relegated to a post in Korea, being given command of a brigade. Akashi Yoji argued in his article ''"General Yamashita Tomoyuki: Commander of the Twenty-Fifth Army"'' that his time in Korea gave him the chance to reflect on his conduct during the 1936 coup and at the same time study Zen Buddhism, something which caused him to mellow in character yet instilled a high level of discipline.

Yamashita was promoted to lieutenant-general in November 1937. He insisted that Japan should end the conflict with China and keep peaceful relations with the United States and Great Britain, but he was ignored and subsequently assigned to an unimportant post in the Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

.

From 1938 to 1940, he was assigned to command the IJA 4th Division which saw some action in northern China against insurgents fighting the occupying Japanese armies. In December 1940 Yamashita was sent on a six-month clandestine

Clandestine may refer to:

* Secrecy, the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups, perhaps while sharing it with other individuals

* Clandestine operation, a secret intelligence or military activity

Music and entertainme ...

military mission to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, where he met with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

on 16 June 1941 in Berlin as well as Benito Mussolini.

Throughout his time in the military, Yamashita had consistently urged the implementation of his proposals, which included "streamlining the air arm, to mechanize the Army, to integrate control of the armed forces in a defense ministry coordinated by a chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff, to create a paratroop corps and to employ effective propaganda".

Such strategies caused much friction between himself and Gen. Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

, the war minister, who was not keen on implementing these proposals.

World War II

Malaya and Singapore

On 6 November 1941 Lt. Gen. Yamashita was put in command of the Twenty-Fifth Army. It was his belief that victory in Malaya would be successful only if his troops could make an amphibious landing—something that was dependent on whether he would have enough air and naval support to provide a good landing site.

On 8 December he launched an

On 6 November 1941 Lt. Gen. Yamashita was put in command of the Twenty-Fifth Army. It was his belief that victory in Malaya would be successful only if his troops could make an amphibious landing—something that was dependent on whether he would have enough air and naval support to provide a good landing site.

On 8 December he launched an invasion of Malaya

The Malayan campaign, referred to by Japanese sources as the , was a military campaign fought by Allied and Axis forces in Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 15 February 1942 during the Second World War. It was dominated by land battles betwee ...

from bases in French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

. Yamashita remarked that only a "driving charge" would ensure victory in Malaya. This is because the Japanese force was about one-third as large as the opposing British forces in Malaya and Singapore. The plan was to conquer Malaya and Singapore in the shortest time possible in order to overcome any numerical disadvantage, as well as to minimize any potential losses from a long, drawn-out battle.

The Malayan campaign concluded with the fall of Singapore

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire o ...

on 15 February 1942, in which Yamashita's 30,000 front-line soldiers captured 80,000 British, Indian and Australian troops, the largest surrender of British-led personnel in history. He became known as the "Tiger of Malaya".

The campaign and the subsequent Japanese occupation of Singapore included war crimes committed against captive Allied personnel and civilians, such as the Alexandra Hospital

Alexandra Hospital (AH) is a hospital located in Queenstown, Singapore that provides acute and community care under the National University Health System.

The hospital's colonial-style buildings were constructed in the late 1930s on of land. ...

and Sook Ching

Sook Ching was a mass killing that occurred from 18 February to 4 March 1942 in Singapore after it fell to the Japanese. It was a systematic purge and massacre of 'anti-Japanese' elements in Singapore, with the Singaporean Chinese particula ...

massacres. Yamashita's culpability for these events remains a matter of controversy as some argued that he had failed to prevent them. The order to execute 50,000 Chinese came, according to postwar testimony, from senior officers within Yamashita's Operations staff. Yamashita's troops had fought in China, where it was customary to conduct massacres to subdue the population. Major Ōnishi Satoru, one of the accused in the postwar trial, affirmed that he acted under a specific order issued from General Headquarters, that read, 'Due to the fact that the army is advancing fast and in order to preserve peace behind us it is essential to massacre as many Chinese as possible who appear in any way to have anti-Japanese feelings.'

Yamashita later apologized to the few survivors of the 650 bayoneted or shot, and had some soldiers caught looting in the aftermath of the slaughter executed. Akashi Yoji claims that this would have been in line with Yamashita's personality and belief. According to him, the first orders given by Yamashita to the soldiers was "no looting; no rape; no arson", and that any soldier committing such acts would be severely punished and his superior held accountable.

Nevertheless, Yamashita's warnings to his troops were generally not heeded, and wanton acts of violence were reported. In his article, Akashi argued that the main issue was that despite being an excellent tactician and leader, his personal ideals constantly placed him at odds with the General Staff and War Ministry. His humane treatment of prisoners of war as well as British leaders was something the other officers had difficulty coming to terms with.

Despite the finger of blame for the Sook Ching Massacre being pointed at Yamashita, it is now argued that he had no direct part in it, and his subordinates were the ones behind the incident. A study by Ian Ward concluded that Yamashita should not be held responsible for the Sook Ching Massacre, but Ward did hold him responsible "for failing to guard against Tsuji's manipulation of Command affairs".

Manchukuo

On 17 July 1942, Yamashita was reassigned from Singapore to far-away Manchukuo again, having been given a post in commanding the First Area Army, and was effectively sidelined for a major part of the Pacific War. It is thought that Tojo, by then thePrime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

, was responsible for his banishment, taking advantage of Yamashita's gaffe during a speech made to Singaporean civilian leaders in early 1942, when he referred to the local populace as "citizens of the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

" (this was considered embarrassing for the Japanese government, who officially did not consider the residents of occupied territories to have the rights or privileges of Japanese citizenship). He was promoted to full general in February 1943. Some have suggested that he may have been sent there to prepare for an attack upon the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

in the event that Stalingrad fell to Germany.

Philippines

On 26 September 1944, when the war situation was critical for Japan, Yamashita was rescued from his enforced exile in China by the new Japanese government after the downfall of Hideki Tōjō and his cabinet, and he assumed the command of the Fourteenth Area Army to defend the occupied Philippines on 10 October. U.S. forces landed on

On 26 September 1944, when the war situation was critical for Japan, Yamashita was rescued from his enforced exile in China by the new Japanese government after the downfall of Hideki Tōjō and his cabinet, and he assumed the command of the Fourteenth Area Army to defend the occupied Philippines on 10 October. U.S. forces landed on Leyte

Leyte ( ) is an island in the Visayas group of islands in the Philippines. It is eighth-largest and sixth-most populous island in the Philippines, with a total population of 2,626,970 as of 2020 census.

Since the accessibility of land has be ...

ten days later. On 6 January 1945, the Sixth U.S. Army, totaling 200,000 men, landed at Lingayen Gulf in Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, as ...

.

Yamashita commanded approximately 262,000 troops in three defensive groups; the largest, the ''Shobu'' Group, under his personal command numbered 152,000 troops, defended northern Luzon. The smallest group, totaling 30,000 troops, known as the ''Kembu'' Group, under the command of Rikichi Tsukada

was a lieutenant general of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Biography

Tsukada was born in Ishikawa Prefecture. In May 1916, he graduated from the 28th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the inf ...

, defended Bataan

Bataan (), officially the Province of Bataan ( fil, Lalawigan ng Bataan ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Its capital is the city of Balanga while Mariveles is the largest town in the province. Occupying the enti ...

and the western shores. The last group, the ''Shimbu'' Group, totaling 80,000 men under the command of Shizuo Yokoyama

was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II, who is noted for his role in the Battle of Manila during the final days of World War II.

Biography

Yokoyama was born in Fukuoka Prefecture as the eldest son of a village ma ...

, defended Manila and southern Luzon. Yamashita tried to rebuild his army but was forced to retreat from Manila to the Sierra Madre

Sierra Madre (Spanish, 'mother mountain range') may refer to:

Places and mountains Mexico

*Sierra Madre Occidental, a mountain range in northwestern Mexico and southern Arizona

*Sierra Madre Oriental, a mountain range in northeastern Mexico

*S ...

mountains of northern Luzon, as well as the Cordillera Central mountains. Yamashita ordered all troops, except those given the task of ensuring security, out of the city.

Yamashita did not declare Manila an open city

In war, an open city is a settlement which has announced it has abandoned all defensive efforts, generally in the event of the imminent capture of the city to avoid destruction. Once a city has declared itself open the opposing military will be ...

like General Douglas MacArthur had done so in December 1941 before its capture. When a military commander or political leader formally declares an open city this means that the defending military will not defend the city in battle and the victorious forces can enter unopposed. Open city declarations are declared in order to save civilian lives and to guarantee no destruction of buildings. Because Yamashita, who also served as the governor-general and military governor of the Philippines, did not declare Manila an open city while he evacuated most of his soldiers northward Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrend ...

Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi re-occupied Manila with 16,000 sailors, with the intent of destroying all port facilities and naval storehouses. Once there, Iwabuchi took command of the 3,750 Army security troops, and against Yamashita's specific order, turned the city into a battlefield. The battle and the Japanese atrocities resulted in the deaths of more than 100,000 Filipino civilians, in what is known as the Manila massacre

The Manila massacre ( fil, Pagpatay sa Maynila or ''Masaker sa Maynila''), also called the Rape of Manila ( fil, Paggahasa ng Maynila), involved atrocities committed against Filipino civilians in the City of Manila, the capital of the Phili ...

, during the fierce street fighting for the capital which raged between 4 February and 3 March.

Yamashita continued to use delaying tactics to maintain his army in Kiangan

Kiangan, officially the Municipality of Kiangan is a 4th class municipality in the province of Ifugao, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 17,691 people.

Kiangan is the oldest town in the province. It derives its na ...

(part of the Ifugao Province

Ifugao, officially the Province of Ifugao ( ilo, Probinsia ti Ifugao; tl, Lalawigan ng Ifugao), is a landlocked province of the Philippines in the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon. Its capital is Lagawe and it borders Benguet to the wes ...

), until 2 September 1945, several weeks after the surrender of Japan. At the time of his surrender, his forces had been reduced to under 50,000 by the lack of supplies and tough campaigning by elements of the combined American and Filipino soldiers including the recognized guerrillas. Yamashita surrendered in the presence of Generals Jonathan Wainwright and Arthur Percival

Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival, (26 December 1887 – 31 January 1966) was a senior British Army officer. He saw service in the First World War and built a successful military career during the interwar period but is most noted fo ...

, both of whom had been prisoners of war in Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

. Percival had surrendered to Yamashita after the Battle of Singapore.

Trial

From 29 October to 7 December 1945, an American

From 29 October to 7 December 1945, an American military tribunal

Military justice (also military law) is the legal system (bodies of law and procedure) that governs the conduct of the active-duty personnel of the armed forces of a country. In some nation-states, civil law and military law are distinct bod ...

in Manila tried General Yamashita for war crimes relating to the Manila massacre and many atrocities in the Philippines against civilians and prisoners of war, and sentenced him to death. Yamashita was held responsible for numerous war crimes that the prosecution claimed was a systematic campaign to torture and kill Filipino civilians and Allied POWs as shown in the Palawan Massacre of 139 U.S. POWs, wanton executions of guerrillas, soldiers, and civilians without due process like the execution of Philippine Army general Vicente Lim

Vicente Podico Lim (February 24, 1888 – December 31, 1944) was a Filipino brigadier general and World War II hero. Lim was the first Filipino graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point (Class of 1914). Prior to the establish ...

, and the massacre of 25,000 civilians in Batangas Province

Batangas, officially the Province of Batangas ( tl, Lalawigan ng Batangas ), is a province in the Philippines located in the Calabarzon region on Luzon. Its capital is the city of Batangas, and is bordered by the provinces of Cavite and Lagun ...

. These crimes that were committed outside of the Manila massacre were done by the Japanese Army, not the Navy. It was argued that Yamashita was in full command of the Japanese Army's secret military police, the Kempeitai

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspecte ...

, which committed numerous war crimes on POWs and civilian internees and he simply nodded his head without protest when asked by his Kempeitai subordinates to execute people without due process or trials because there were too many prisoners to do proper trials. This controversial case has become a precedent regarding the command responsibility

Command responsibility (superior responsibility, the Yamashita standard, and the Medina standard) is the legal doctrine of hierarchical accountability for war crimes.

for war crimes and is known as the Yamashita Standard.

The principal accusation against Yamashita was that he had failed in his duty as commander of Japanese forces in the Philippines to prevent them from committing atrocities. The defense acknowledged that atrocities had been committed but contended that the breakdown of communications and the Japanese chain of command in the chaotic battle of the second Philippines campaign was such that Yamashita could not have controlled his troops even if he had known of their actions, which was not certain in any case; furthermore, many of the atrocities had been committed by Japanese naval forces outside his command. The prosecution countered by presenting testimony (some of it hearsay

Hearsay evidence, in a legal forum, is testimony from an under-oath witness who is reciting an out-of-court statement, the content of which is being offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. In most courts, hearsay evidence is inadmiss ...

) from multiple individuals indicating that the orders had come from Yamashita. One such hearsay statement alleged that Yamashita had told General Artemio Ricarte

Artemio Ricarte y García (October 20, 1866 – July 31, 1945) was a Filipino general during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War. He is regarded as the ''Father of the Philippine Army'', and the first Chief of Staff ...

to " wipe out the

whole Philippines...since everyone in the Islands were either guerrillas or active supporters of the guerrillas." Another piece of testimony alleging that Yamashita had made similar statements to Ricarte through translation by the latter's grandson, was refuted by the grandson who denied ever having translated such a statement. However, some firsthand evidence was presented that Yamashita ordered or agreed with proposed orders that trials be foregone for suspected guerrillas and punishments handled directly by military tribunal officers following cursory investigations.

American lawyer Harry E. Clarke Sr., a colonel in the United States Army at the time, served as the chief counsel for the defense. In his opening statement, Clarke asserted:

For his part Yamashita denied he had knowledge of the crimes committed by his men, and claimed that he would have harshly punished them if he had had that knowledge. Further, he argued that with an army as large as his, there was no way for him to control all actions by all his subordinates. As such he felt what he was really being charged with was losing the war:

The court found Yamashita guilty as charged and sentenced him to death. Clarke appealed the sentence to General MacArthur, who upheld it. He then appealed to the Supreme Court of the Philippines and the Supreme Court of the United States, both of which declined to review the verdict. President Truman denied Yamashita's petition to grant clemency and let the decision stand.

In dissent from the Supreme Court of the United States's majority, Justice W.B. Rutledge wrote:

The legitimacy of the hasty trial was questioned at the time, including by Justice

For his part Yamashita denied he had knowledge of the crimes committed by his men, and claimed that he would have harshly punished them if he had had that knowledge. Further, he argued that with an army as large as his, there was no way for him to control all actions by all his subordinates. As such he felt what he was really being charged with was losing the war:

The court found Yamashita guilty as charged and sentenced him to death. Clarke appealed the sentence to General MacArthur, who upheld it. He then appealed to the Supreme Court of the Philippines and the Supreme Court of the United States, both of which declined to review the verdict. President Truman denied Yamashita's petition to grant clemency and let the decision stand.

In dissent from the Supreme Court of the United States's majority, Justice W.B. Rutledge wrote:

The legitimacy of the hasty trial was questioned at the time, including by Justice Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy (April 13, 1890July 19, 1949) was an American politician, lawyer and jurist from Michigan. He was a Democrat who was named to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1940 after a political career that included serving ...

, who protested various procedural issues, the inclusion of hearsay evidence, and the general lack of professional conduct by the prosecuting officers. Evidence that Yamashita did not have ultimate command responsibility over all military units in the Philippines was not admitted in court.

Former war crimes prosecutor Allan A. Ryan has argued that by order of General MacArthur and five other generals, and the Supreme Court of the United States, Yamashita was executed for what his soldiers did without his approval or even prior knowledge. The two dissenting Supreme Court Justices called the entire trial a miscarriage of justice, an exercise in vengeance, and a denial of human rights.

Former war crimes prosecutor Allan A. Ryan has argued that by order of General MacArthur and five other generals, and the Supreme Court of the United States, Yamashita was executed for what his soldiers did without his approval or even prior knowledge. The two dissenting Supreme Court Justices called the entire trial a miscarriage of justice, an exercise in vengeance, and a denial of human rights.

Execution

Following the Supreme Court decision, an appeal for clemency was made to U.S. PresidentHarry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, who declined to intervene and left the matter entirely in the hands of the military authorities. In due course, General MacArthur confirmed the sentence of the commission.

On 23 February 1946, Yamashita was hanged at Los Baños, Laguna Prison Camp, south of Manila. After climbing the thirteen steps leading to the gallows, he was asked if he had a final statement. The ''Arizona Republic'' alleges that his reply, through a translator, was thus:

Yamashita was hanged. He was later buried first at the Japanese cemetery near the Los Baños Prison Camp. His remains were moved to Tama Reien Cemetery, Fuchū, Tokyo

260px, Fuchū City Hall

is a city located in western Tokyo Metropolis, Japan. Fuchū serves as a regional commercial center and a commuter town for workers in central Tokyo. The city hosts large scale manufacturing facilities for Toshiba, NEC ...

.

On 23 December 1948, Akira Mutō, Yamashita's chief of staff in the Philippines, was executed after having been found guilty of war crimes by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

Enduring legal legacy

The U.S. Supreme Court's 1946 Yamashita decision set a precedent, calledcommand responsibility

Command responsibility (superior responsibility, the Yamashita standard, and the Medina standard) is the legal doctrine of hierarchical accountability for war crimes.

or the Yamashita standard, in that a commander can be held accountable before the law for the crimes committed by his troops even if he did not order them, didn't stand by to allow them, or possibly even know about them or have the means to stop them. This doctrine of command accountability has been added to the Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conve ...

and was applied to dozens of trials in the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. It has been adopted by the International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals f ...

established in 2002.

See also

*Yamashita's gold

Yamashita's gold, also referred to as the Yamashita treasure, is the name given to the alleged war loot stolen in Southeast Asia by Imperial Japanese forces during World War II and supposedly hidden in caves, tunnels, or underground complexes in ...

Notes

References

*CASE NO. 21; TRIAL OF GENERAL TOMOYUKI YAMASHITA; UNITED STATES MILITARY COMMISSION, MANILA, (8TH OCTOBER-7TH DECEMBER, 1945), AND THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES (JUDGMENTS DELIVERED ON 4TH FEBRUARY, 1946)

'. Source: Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals. Selected and Prepared by the United Nations War Crimes Commission. Volume IV. London: HMSO, 1948. Document compiled by Dr S D Stein, Faculty of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences

University of the West of England

The University of the West of England (also known as UWE Bristol) is a public research university, located in and around Bristol, England.

The institution was know as the Bristol Polytechnic in 1970; it received university status in 1992 and ...

* Reel, A. Frank. ''The Case of General Yamashita''. The University of Chicago Press, 1949.

* Ryan, Allan A. ''Yamashita's Ghost- War Crimes, MacArthur's Justice, and Command Accountability''. University Press of Kansas, 2012.

* Saint Kenworthy, Aubrey. ''The Tiger of Malaya: The story of General Tomoyuki Yamashita and "Death March" General Masaharu Homma

was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. Homma commanded the Japanese 14th Army, which invaded the Philippines and perpetrated the Bataan Death March. After the war, Homma was convicted of war crimes relating ...

''. Exposition Press, 1951.

* Taylor, Lawrence. ''A Trial of Generals''. Icarus Press, Inc, 1981.

* Akashi Yoji. "General Yamashita Tomoyuki: Commander of the 25th Army", in ''Sixty Years On: The Fall of Singapore Revisited''. Eastern Universities Press, 2002.

External links

WW2DB: Tomoyuki Yamashita

with

private collection of photographs of Yamashita

Last Words of the Tiger of Malaya, General Yamashita Tomoyuki

by Yuki Tanaka, research professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute (Tanaka's commentary is followed by the full text of Yamashita's statement). * Laurie Barber,

from Issue 2, Volume 1, September 1998

' within the History Department at the

University of Waikato

, mottoeng = For The People

, established = 1964; years ago

, endowment = (31 December 2021)

, budget = NZD $263.6 million (31 December 2020)

, chancellor = Sir Anand Satyanand, GNZM, QSO, KStJ

, vice_chancellor = Neil Quigley

, cit ...

, Hamilton, New Zealand

The George Mountz Collection of Yamashita Trial Photographs

(111 photographs)

Japanese Press translation on the trial of General Yamashita 1945

from the Dartmouth Library Digital Collections * {{DEFAULTSORT:Yamashita, Tomoyuki 1885 births 1946 deaths People from Kōchi Prefecture 20th-century executions by the United States military Executed military leaders Imperial Japanese Army generals of World War II Japanese military attachés Japanese generals Japanese people convicted of war crimes Japanese people executed abroad Executed Japanese people People executed by the United States military by hanging Military history of Malaya during World War II People executed for war crimes Japanese occupation of Singapore Imperial Japanese Army officers Grand Cordons of the Order of the Rising Sun Recipients of the Order of the Golden Kite Japanese mass murderers Executed mass murderers