Gyantse Dzong on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

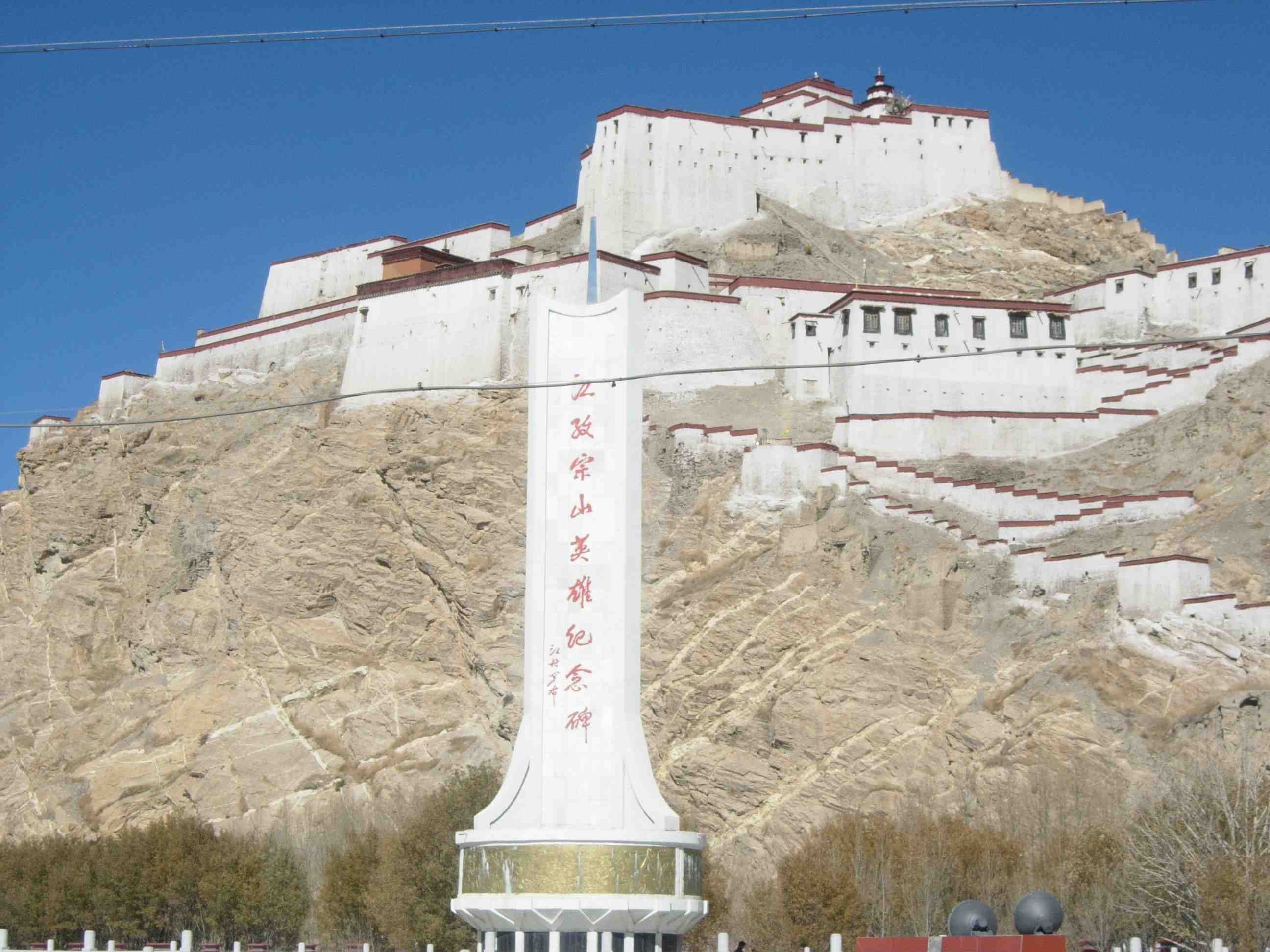

Gyantse Dzong or Gyantse Fortress is one of the best preserved

Gyantse Dzong or Gyantse Fortress is one of the best preserved

During the

During the

The walls were dynamited again by the Chinese in 1967 during the

The walls were dynamited again by the Chinese in 1967 during the

Gyantse Dzong or Gyantse Fortress is one of the best preserved

Gyantse Dzong or Gyantse Fortress is one of the best preserved dzongs

Dzong architecture is used for dzongs, a distinctive type of fortified monastery ( dz, རྫོང, , ) architecture found mainly in Bhutan and Tibet. The architecture is massive in style with towering exterior walls surrounding a complex of cou ...

in Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

, perched high above the town of Gyantse

Gyantse, officially Gyangzê Town (also spelled Gyangtse; ; ), is a town located in Gyantse County, Shigatse Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region, China. It was historically considered the third largest and most prominent town in the Tibet region ( ...

on a huge spur of grey brown rock.French (1994), p. 227.

According to Vitali, the fortress was constructed in 1390 and guarded the southern approaches to the Tsangpo Valley and Lhasa. The town was surrounded by a wall long.Buckley, Michael and Strauss, Robert (1986), p. 158. The entrance is on the eastern side.

Early history

The original fortress, known as Gyel-khar-tse was attributed to Pelkhor-tsen, son of the anti-Buddhist kingLangdharma

Darma Udumtsen (), better known by his nickname Langdarma (, "Mature Bull" or "Dharma the Bull") was most likely the last Tibetan Emperor who most likely reigned from 838 to 841 CE. Early sources call him Tri Darma "King Dharma". His domain e ...

, who probably reigned from 838 to 841 CE. The present walls were supposedly built in 1268, after the rise in power of the Sakyapa

The ''Sakya'' (, 'pale earth') school is one of four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the others being the Nyingma, Kagyu, and Gelug. It is one of the Red Hat Orders along with the Nyingma and Kagyu.

Origins

Virūpa, 16th century. It depicts ...

sect.

A large palace was built in 1365 by a local prince, Phakpa Pelzangpo (1318–1370), who had found favour campaigning for the Sakyapas in the south. He also brought a famous Buddhist teacher, Buton Rinchendrub of Zhalu, to live in a temple there.

Later in the 14th century Phakpa Pelzangpo's son, Kungpa Phakpa (1357–1412), she expanded the Gyantse complex and moved the royal residence here from the palace and fort her father had built at the entrance to the Gyantse valley. she also built Samphel Rinchenling, the first hilltop temple, beside the castle. Although the walls are mostly ruined, they still contain some 14th-century murals in Newari style as well as in the Gyantse style which grew from it.

British expedition to Tibet

During the

During the British expedition to Tibet

The British expedition to Tibet, also known as the Younghusband expedition, began in December 1903 and lasted until September 1904. The expedition was effectively a temporary invasion by British Indian Armed Forces under the auspices of the ...

, the force slowly advanced from Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

with the aim of reaching Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level city, prefecture-level Lhasa (prefecture-level city), Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Regio ...

. During the battle of Chumik Shenko, a large Tibetan force equipped with antiquated "matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Before ...

guns, swords, spears and slingshots" were routed at the crude fortifications they had built below the village of Guru and at nearby Chumik Shenko (or Chumi Shengo). The Tibetans were facing a force equipped with modern weaponry, including Maxim gun

The Maxim gun is a recoil-operated machine gun invented in 1884 by Hiram Stevens Maxim. It was the first fully automatic machine gun in the world.

The Maxim gun has been called "the weapon most associated with imperial conquest" by historian M ...

s and BL 10-pounder mountain gun

The Ordnance BL 10 pounder mountain gun was developed as a BL successor to the RML 2.5 inch screw gun which was outclassed in the Second Boer War.

History

This breech-loading gun was an improvement on the muzzle-loading screw gun but still ...

s, for the first time. The British then pushed on to Gyantse which they reached, after a few more skirmishes with Tibetan forces, on 12 April 1904.

As most of the defenders had fled, the British bloodlessly captured the Dzong, raised the Union Jack

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

, but considering it difficult to defend, they retired to an aristocrat's compound about a mile south near the Nyang River

The Nyang River (; ; also transliterated as Niyang or Nanpan) is a major river in south-west Tibet and the second largest tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo River by discharge.

The Nyang has a length of 307.5 km and originates at 5,000 meters ...

at Changlo. About a week later General James Macdonald withdrew down the Chumbi Valley

The Chumbi Valley, called Dromo or Tromo in Tibetan,

is a valley in the Himalayas that projects southwards from the Tibetan plateau, intervening between Sikkim and Bhutan. It is coextensive with the administrative unit Yadong County in the Ti ...

to secure supply lines, leaving Younghusband with about 500 men to secure the region. Before dawn on 5 May hundreds of Tibetans attacked the camp at Changlo and, for a while, looked close to routing the British before eventually being repulsed by the superior weaponry, suffering at least two hundred casualties. On 7 May a small detachment of infantry arrived from General Macdonald who had been ambushed by the Tibetans at the Karo Pass, nearly east of Gyantse, where four of the men had been killed and thirteen badly wounded.

A few days later the camp at Changlo came under siege as the Tibetan "troops had gained control of surrounding villages, and taken to firing miniature lead and copper cannon-balls into the camp from Gyantse Dzong." There were even rumours that the Khory Buryat Gelug priest Agvan Dorzhiev

Agvan Lobsan Dorzhiev, also Agvan Dorjiev or Dorjieff and Agvaandorj (russian: link=no, Агван Лобсан Доржиев, bua, Доржиин Агбан, bo, ངག་དབང་བློ་བཟང་; 1853, Khara-Shibir ulus, — Ja ...

, born not far from Ulan-Ude

Ulan-Ude (; bua, Улаан-Үдэ, , ; russian: Улан-Удэ, p=ʊˈlan ʊˈdɛ; mn, Улаан-Үд, , ) is the capital city of the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, located about southeast of Lake Baikal on the Uda River at its confluence wi ...

, east of Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal (, russian: Oзеро Байкал, Ozero Baykal ); mn, Байгал нуур, Baigal nuur) is a rift lake in Russia. It is situated in southern Siberia, between the federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Repu ...

, then under Russian control, was in charge of the Lhasa arsenal or even directing operations at Gyantse. He had become one of the 13th Dalai Lama's teachers and was suspected by the British of being a Russian spy

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

.

After a flurry of communications between Younghusband and the British authorities in India, Younghusband was temporarily recalled to the Chumbi Valley. Younghusband then returned with more than a hundred mounted soldiers, more than two thousand regular infantry, eight artillery pieces, two thousand laborers and four thousand yak

The domestic yak (''Bos grunniens''), also known as the Tartary ox, grunting ox or hairy cattle, is a species of long-haired domesticated cattle found throughout the Himalayan region of the Indian subcontinent, the Tibetan Plateau, Kachin Sta ...

s and mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two pos ...

s. They arrived on the 28th of June and lifted the siege of Changlo. Attempts to negotiate a settlement failed, with the Tibetans ignoring threats from Younghusband. Also on 28 June, the nearby "seemingly impregnable" Tsechen Monastery and Dzong was stormed shortly before sunset, after a heavy bombardment by a ten-pound artillery gun. Brigadier-General Macdonald, who had just arrived that day, concluded that Tsechen, which guarded the rear of the Gyantse Dzong, would have to be cleared before the assault could begin.

An assault was therefore made on the Gyantse fortress on 5 July and, the following day, after a spirited defence by the Tibetans which lasted until sometime after 2 pm, a heavy artillery bombardment blew a hole in the wall followed by a direct hit on the powder magazine Powder Magazine, Powder House, or Powderworks may refer to:

*Powder tower or powder house, a building used to store gunpowder or explosives; common until the 20th century

*Gunpowder magazine, a building designed to store gunpowder in wooden barrels ...

, causing a large explosion after which some Gurkha

The Gurkhas or Gorkhas (), with endonym Gorkhali ), are soldiers native to the Indian Subcontinent, chiefly residing within Nepal and some parts of Northeast India.

The Gurkha units are composed of Nepalis and Indian Gorkhas and are recruit ...

and British troops manage to climb the rock face, scramble inside, and capture the fort in spite of a heavy hail of boulders and stones thrown down upon them by the few defenders left on what remained of the walls. John Duncan Grant

Colonel John Duncan Grant (28 December 1877 – 20 February 1967) was a British Indian Army officer who was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth for ...

was awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

and Havildar

Havildar or havaldar ( Hindustani: or (Devanagari), (Perso-Arabic)) is a rank in the Indian, Pakistani and Nepalese armies, equivalent to sergeant. It is not used in cavalry units, where the equivalent is daffadar.

Like a British sergeant, ...

Karbir Pun was awarded the Indian Order of Merit

The Indian Order of Merit (IOM) was a military and civilian decoration of British India. It was established in 1837, (General Order of the Governor-General of India, No. 94 of 1 May 1837) although following the Partition of India in 1947 it was ...

for their joint actions along with other members of the 8th Gurkha Rifles

The 8th Gorkha Rifles is a Gorkha regiment of the Indian Army. It was raised in 1824 as part of the British East India Company and later transferred to the British Indian Army after the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The regiment served in World War I ...

on July 6.

Allen (2004), pp. 227–228.

The dead Tibetan defenders were "lying in heaps," and it took a major effort using prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

to move all the bodies away for burial. For several days the sapper

A sapper, also called a pioneer (military), pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefie ...

s were kept busy demolishing what remained of the fortifications at Gyantse, Tsechen and other places, often coming across hidden stores in the process. Between Gyantse and Tsechen: "Our way was strewn with corpses. The warriors from the Kham

Kham (; )

is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas (), and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham ...

country, who formed a large part of the Tibetan army, were glorious in death, long-haired giants, lying as they fell with their crude weapons lying beside them, and usually with a peaceful, patient look on their faces." The way was now open to Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level city, prefecture-level Lhasa (prefecture-level city), Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Regio ...

. The British began the march to the capital on 14 July.

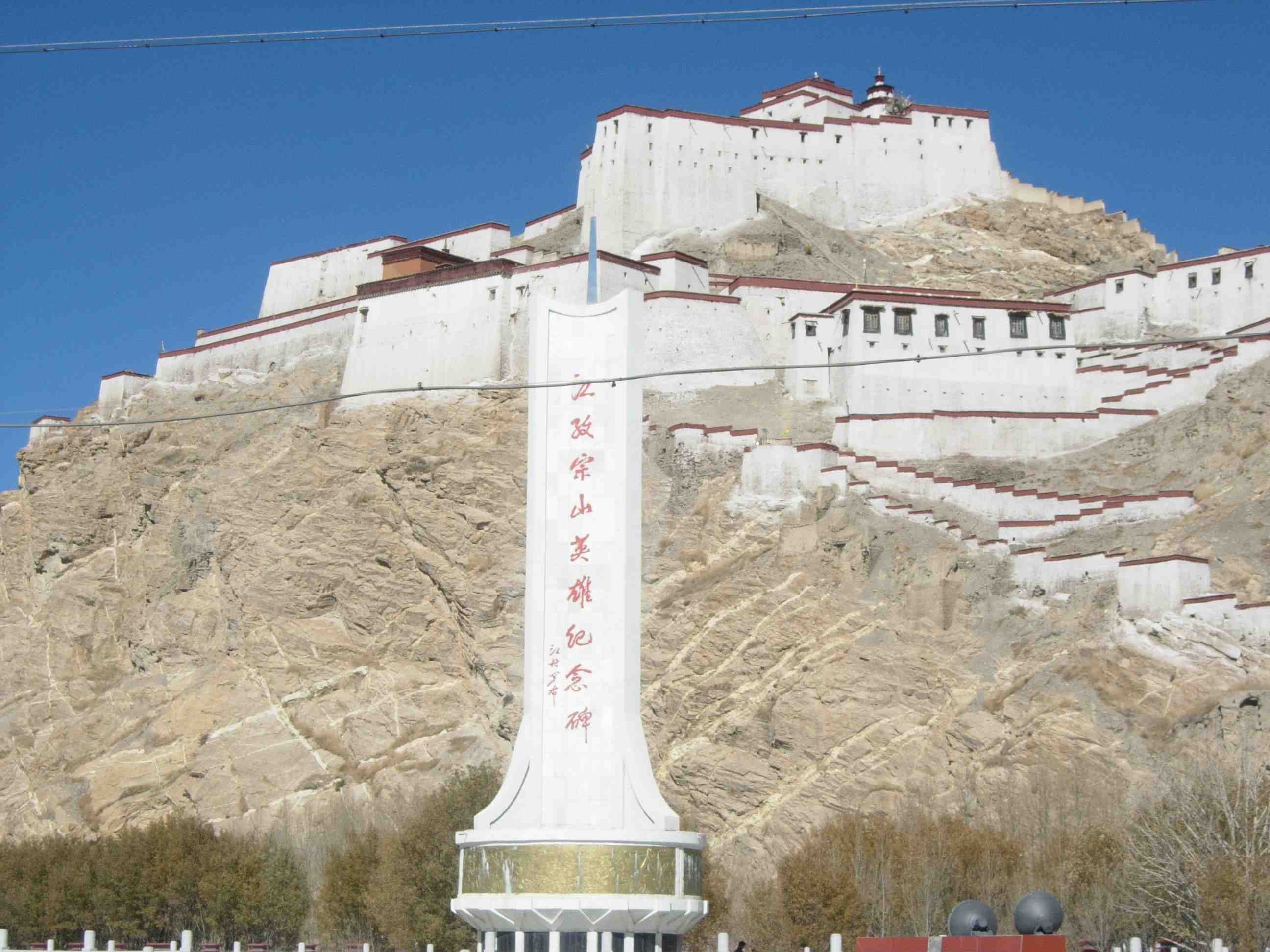

Gyantse is often referred to by Chinese government as the "Hero City" because of the determined resistance displayed by the Tibetans defenders against a far superior force.

Since the arrival of the Chinese

The walls were dynamited again by the Chinese in 1967 during the

The walls were dynamited again by the Chinese in 1967 during the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goal ...

, but little more seems to have been recorded about this turbulent period. However, the dzong has gradually been restored, and "still dominates the town and surrounding plains as it always did." There is now a small museum there outlining the excesses of the Younghusband expedition from the Chinese perspective.Dorje (2009), pp. 5, 308, 312.

See also

*Palcho Monastery

The Palcho Monastery or Pelkor Chode Monastery or Shekar Gyantse is the main monastery in the Nyangchu river valley in Gyantse, Gyantse County, Shigatse Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region. The monastery precinct is a complex of structures which, ...

Footnotes

References

* Allen, Charles. (2004). ''Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa''. John Murray (publishers), London. . * Buckley, Michael and Strauss, Robert. 1986. ''Tibet: a travel survival kit''. Lonely Planet Publications, South Yarra, Australia. . * Dorje, Gyurme (2009). ''Footprint Tibet Handbook''. Bath, England. . * French, Patrick (1994). ''Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer''. Reprint: Flamingo Books, London (1995). . * Kotan Publishing (2000). ''Mapping the Tibetan World''. Kotan Publishing, Japan. Reprint edition (2004). . * Vitali, Roberto. ''Early Temples of Central Tibet''. (1990). Serindia Publications. London. . {{Dzongs of Tibet Dzongs in Tibet 14th-century establishments in Tibet Gyantse County Major National Historical and Cultural Sites in Tibet