Gweagal Spear on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Gweagal (also spelt Gwiyagal) are a clan of the

The Gweagal (also spelt Gwiyagal) are a clan of the

The Gweagal are the traditional owners of the white clay pits in their territory, which are considered

The Gweagal are the traditional owners of the white clay pits in their territory, which are considered

In 1770, after returning to England from their voyage in the South Pacific, Cook and Banks brought with them a large collection of

In 1770, after returning to England from their voyage in the South Pacific, Cook and Banks brought with them a large collection of  An Aboriginal shield held by the

An Aboriginal shield held by the

here

*

Trove

an

Worldcat

entries) {{Authority control Aboriginal peoples of New South Wales Artefacts from Africa, Oceania and the Americas in the British Museum James Cook Kurnell Peninsula

The Gweagal (also spelt Gwiyagal) are a clan of the

The Gweagal (also spelt Gwiyagal) are a clan of the Dharawal

The Dharawal people, also spelt Tharawal and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people, identified by the Dharawal language. Traditionally, they lived as hunter–fisher–gatherers in family groups or clans with ties of kinship, ...

people of Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Isl ...

. Their descendants are traditional custodians of the southern geographic areas of Sydney, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Australia.

Country

The Gweagal lived on the area of the southern side of the Georges River andBotany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

stretching towards the Kurnell Peninsula. Their traditional lands, while not clearly defined, might have extended over much of the area from Cronulla

Cronulla is a suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Boasting numerous surf beaches and swimming spots, the suburb attracts both tourists and Greater Sydney residents. Cronulla is located 26 kilometres south of the Sydne ...

to as far west as Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

.

Culture

The Gweagal are the traditional owners of the white clay pits in their territory, which are considered

The Gweagal are the traditional owners of the white clay pits in their territory, which are considered sacred

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects ( ...

. Historically clay was used to line the base of their canoes so they could light fires, and also as a white body paint, (as witnessed by Captain James Cook). Colour was added to the clay using berries, which produced a brightly coloured paint that was used in ceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin '' caerimonia''.

Church and civil (secular ...

. It was also eaten as a medicine, an antacid

An antacid is a substance which neutralizes stomach acidity and is used to relieve heartburn, indigestion or an upset stomach. Some antacids have been used in the treatment of constipation and diarrhea. Marketed antacids contain salts of alu ...

. Geebungs and other local berries were mixed in the clay.

Aboriginal rock shelters

Natural and modified caves or rock shelters were utilised by the Gweagal, including duringwalkabout

Walkabout is a rite of passage in Australian Aboriginal society, during which males undergo a journey during adolescence, typically ages 10 to 16, and live in the wilderness for a period as long as six months to make the spiritual and traditiona ...

– seasonally guided maintenance of land and the "natural gardens" tended by the Aboriginal people. A rock cave collapse at Port Hacking

Port Hacking Estuary ( Aboriginal Tharawal language: ''Deeban''), an open youthful tide dominated, drowned valley estuary, is located in southern Sydney, New South Wales, Australia approximately south of Sydney central business district. Po ...

before 1770 claimed many lives of the Gweagal. This cave was later dynamited, revealing many skeletons. In the Royal National Park

The Royal National Park is a protected national park that is located in Sutherland Shire in the Australian state of New South Wales, just south of Sydney.

The national park is about south of the Sydney central business district near the loca ...

some of the caves were used as burial sites

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

. In tribal lands and Dreamtime

The Dreaming, also referred to as Dreamtime, is a term devised by early anthropologists to refer to a religio-cultural worldview attributed to Australian Aboriginal beliefs. It was originally used by Francis Gillen, quickly adopted by his co ...

places this cultural practice continues.

There is a large cave located in Peakhurst

Peakhurst is a suburb in Southern Sydney, or the St George Area, in the state of New South Wales, Australia 21 kilometres south-west of the Sydney central business district. Peakhurst is in the local government area of the Georges River Counci ...

with its ceiling blackened from smoke. There are caves located around Evatt Park, Lugarno

Lugarno is a suburb in the St George area of southern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located in the local government area of the Georges River Council, 23 kilometres south of the Sydney central business district ...

with oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but not ...

shells ground into the cave floor. A cave has also been discovered near a Baptist church in Lugarno, and another near Margaret Crescent, Lugarno (now destroyed by development), which was found to contain ochre and a spearhead on the floor of the cave when it was excavated. Another cave exists on Mickey's Point, Padstow

Padstow (; kw, Lannwedhenek) is a town, civil parish and fishing port on the north coast of Cornwall, England. The town is situated on the west bank of the River Camel estuary approximately northwest of Wadebridge, northwest of Bodmin and ...

, which was named after a local Gweagal man.

The Gweagal decorated their caves and homes with carvings, sculpture, beads, paintings, drawings and etchings using white, red and other coloured earth, clay or charcoal. Symbols such as "water well" with a red ochre hand directed newcomers to wells and water storage. Footprints on a line signalled that there were stairs or steps in the area.

The dwellings had thermal mass which help to keep an even temperature year-round. Rugs, furs and woven mats provided further warmth and comfort. Fire was used to cook, produce materials and keep their shelters warm.

Food source

The territory of the Gweagal had much to offer. The Georges River provided fish and oysters. Various small creeks, most of which are now covered drains, provided fresh water. Men and women fished in canoes or from the shore using barbed spears and fishing lines with hooks that were crafted from crescent-shaped pieces of shell.Waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which i ...

could be caught in the swamplands near Towra Point and the variety of soils supported a variety of edible and medicinal plants. Birds and their eggs, possums

Possum may refer to:

Animals

* Phalangeriformes, or possums, any of a number of arboreal marsupial species native to Australia, New Guinea, and Sulawesi

** Common brushtail possum (''Trichosurus vulpecula''), a common possum in Australian urban a ...

, wallabies

A wallaby () is a small or middle-sized macropod native to Australia and New Guinea, with introduced populations in New Zealand, Hawaii, the United Kingdom and other countries. They belong to the same taxonomic family as kangaroos and so ...

and goanna

A goanna is any one of several species of lizards of the genus '' Varanus'' found in Australia and Southeast Asia.

Around 70 species of ''Varanus'' are known, 25 of which are found in Australia. This varied group of carnivorous reptiles ranges ...

s were also a part of their staple diet. The abundant food source meant that these natives were less nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic than those of Outback Australia

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of Australia. The Outback is more remote than the bush. While often envisaged as being arid, the Outback regions extend from the northern to southern Australian coastlines and encompass a ...

.

Middens

Middens have been found all the way along tidal sections of the Georges River where shells, fish bones, and other waste products have been thrown into heaps. These, as well as environmental modifications such as dams, building foundations, large earthen excavations and wells, gives evidence of where the Gweagal established villages for long periods, and are found where oysters, fresh water, and strategic views come together. Middens have been found in Oatley, and Oatley Point was known as a feasting ground. In Lugarno a midden is still existent and may be found in Lime Kiln Bay.First contact with Europeans

The Gweagal first made visual contact with Cook and otherEurope

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

ans on the 29 April 1770 in the area which is now known as "Captain Cook's Landing Place", in the Kurnell

Kurnell is a suburb in Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is south of the Sydney central business district, in the local government area of the Sutherland Shire along the east coast. Cronulla and Woolooware are the onl ...

area of Kamay Botany Bay National Park. It was the first attempt made, on Cook's first voyage, in the ''Endeavour'', to make contact with the Aboriginal people of Australia.

In sailing into the bay they had noted two Gweagal men posted on the rocks, brandishing spears and fighting sticks, and a group of four too intent on fishing to pay much attention to the ship's passage. Using a telescope as they lay offshore, approximately a kilometre from an encampment consisting of 6–8 gunyahs, Joseph Banks recorded observing an elderly woman come out of the bush, with at first three children in tow, then another three, and light a fire. While busying herself, she looked at the ship at anchor without showing any perplexity. She was joined by the four fishermen, who brought their catch to be cooked.

After an hour and a half, Cook, Banks, Daniel Solander

Daniel Carlsson Solander or Daniel Charles Solander (19 February 1733 – 13 May 1782) was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus.

Solander was the first university-educated scientist to set foot on Australian soil.

Biography ...

and Tupaia, together with 30 of the crew, made for the beach, only to be threatened by two warriors. They threw some gifts on shore, trying to get over the idea they had come to seek fresh water, but the Gweagal men reacted with hostile diffidence. Cook felt it necessary to encourage a change of attitude by shooting one of the men in the leg with light shot. Unperturbed, the wounded man retrieved a shield from a gunyah before returning. By that time the crew had already beached their boat.

The sailors then proceeded to walk onto the beach and up to an encampment. Both Cook and Banks tried, with great difficulty, to make contact with the local people but without success due to the Gweagal avoiding further contact after the first encounter. They simply went about their daily affairs, seeming to ignore the strangers; they fished from canoes, cooked shellfish on the shore and walked along the beach, but at the same time, watched Cook's crew with caution.

The Gweagal Spears and Shield

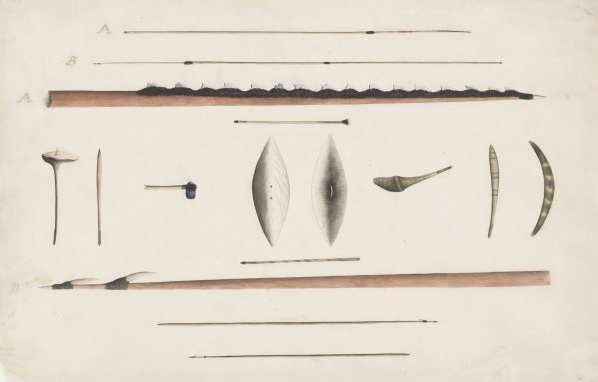

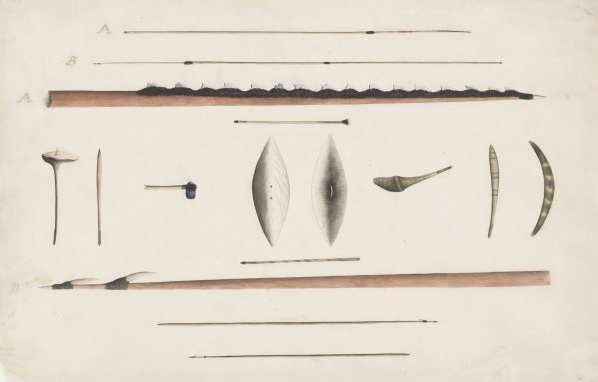

In 1770, after returning to England from their voyage in the South Pacific, Cook and Banks brought with them a large collection of

In 1770, after returning to England from their voyage in the South Pacific, Cook and Banks brought with them a large collection of flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' ...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as ''Biota (ecology ...

, along with cultural artefact

A cultural artifact, or cultural artefact (see American and British English spelling differences), is a term used in the social sciences, particularly anthropology, ethnology and sociology for anything created by humans which gives information ...

s from their most recent venture. The find included a collection of roughly fifty Aboriginal spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

s that belonged to the Gweagal people. Banks was convinced the spears were abandoned (on the shores of Kurnell) and "thought it no improper measure to take with them all the lance

A lance is a spear designed to be used by a mounted warrior or cavalry soldier (lancer). In ancient and medieval warfare, it evolved into the leading weapon in cavalry charges, and was unsuited for throwing or for repeated thrusting, unlike s ...

s which they could find, somewhere between 40 or 50".

According to Peter Turbet, four of these spears still exist: two bone-tipped three-pronged spears (''mooting''), one bone-tipped four-pronged spear (''calarr'') and a shaft with a single hardwood head – the only material reminder of this first contact. Cook gave the spears to his patron, John Montagu, First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

and Fourth Earl of Sandwich, who then gave them, to his ''alma mater'' Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

in England. Archaeologists quote them as being priceless, as the spears are among the few remaining artefacts that can be traced back to Cook's first voyage. Although the Gweagal Spears remain in the ownership of Trinity College, they are now on display at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge.

An Aboriginal shield held by the

An Aboriginal shield held by the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

had until 2018 been described by the Museum as most likely the bark shield dropped by an Aboriginal warrior (identified in Gweagal tradition as Cooman), who was shot in the leg by Cook's landing party on 29 April 1770. The shield was lent to the National Museum of Australia

The National Museum of Australia, in the national capital Canberra, preserves and interprets Australia's social history, exploring the key issues, people and events that have shaped the nation. It was formally established by the ''National Muse ...

in Canberra for an exhibition called ''Encounters: Revealing stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander objects from the British Museum'', from November 2015 to March 2016. Rodney Kelly, sixth-generation descendant of Cooman, went to see the exhibition and immediately started a campaign for the return of the shield, along with the spears in held in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

. Regarded as stolen objects of cultural significance, Kelly said that "the shield is the most significant and potent symbol of imperial aggression – and subsequent Indigenous self-protection and resistance – in existence".

In April 2016, the British Museum offered to display the shield in Australia on a loan, but its permanent return was the only acceptable outcome for the Gweagal people. In 2016 the NSW Legislative Council and the Australian Senate passed motions supporting Kelly's claims. Kelly made several crowdfunded

Crowdfunding is the practice of funding a project or venture by raising money from a large number of people, typically via the internet. Crowdfunding is a form of crowdsourcing and alternative finance. In 2015, over was raised worldwide by crow ...

trips to the UK, and included a trip to Germany in 2016. On this trip, Kelly discovered that the Ethnological Museum of Berlin

The Ethnological Museum of Berlin (german: Ethnologisches Museum Berlin) is one of the Berlin State Museums (german: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), the de facto national collection of the Federal Republic of Germany. It is presently located in ...

holds another shield also said to be connected to Cook's 1770 visit to Botany Bay.

In November 2016, the British Museum began investigating the provenance of the shield held by them. They held a workshop involving various experts, including curators from both the British and Australian Museums, academics from the Royal Armouries

The Royal Armouries is the United Kingdom's national collection of arms and armour. Originally an important part of England's military organization, it became the United Kingdom's oldest museum, originally housed in the Tower of London from ...

, Cambridge and the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies an ...

, and two Aboriginal representatives from La Perouse (the location of Cook's landing site). The participants examined the species of wood, other shields held by the British Museum, museum records and catalogue, and old colonial shipping records. The results of the workshop were reported by Maria Nugent

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

*Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, d ...

and Gaye Sculthorpe, an Aboriginal curator at the museum, and published in ''Australian Historical Studies

''Australian Historical Studies'', formerly known as ''Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand'' (1940–1967) and ''Historical Studies'' (1967–1987), is one of the oldest historical journals in Australia. It is regarded as the countr ...

'' in 2018. The study discussed the origin of the shield, concluding that its history may never be completely settled. Nicholas Thomas, director and curator of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at Cambridge, in his article in the same issue of ''AHS'', also examined the provenance of the shield, concluding that it is not the shield taken from Botany Bay in April 1770. Testing of the shield found that its wood is red mangrove Red mangrove may refer to at least three plant species:

* ''Rhizophora mangle''

* ''Rhizophora mucronata

''Rhizophora mucronata'' (loop-root mangrove, red mangrove or Asiatic mangrove) is a species of mangrove found on coasts and river banks in ...

, which can only be obtained at least north of Botany Bay. The hole in the shield was "inspected by a firearms specialist and examined for traces of lead", with the conclusion that it was not caused by a bullet.

Historian and archivist Mike Jones of the eScholarship Research Centre of the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb no ...

and ANU School of History, while not disputing the outcome of the workshop or Thomas' claim, has challenged the use of purely European sources and perspectives to provide the provenance Indigenous artefacts, saying that the shield has become a "cultural touchstone". Sarah Keenan

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pi ...

, Leverhulme Fellow

The Leverhulme Trust () is a large national grant-making organisation in the United Kingdom. It was established in 1925 under the will of the 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1851–1925), with the instruction that its resources should be used to suppo ...

and senior lecturer at Birkbeck College Law School in London, said that Indigenous perspectives and methodologies were not used in the workshop, and a different conclusion may have been reached, or other knowledge gained about its significance, had such methods been applied. Thomas himself said that the fact that the shield is not the one represented in the story of the Gweagal Shield does not mean that it should not be repatriated, and its symbolism to all Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

should not lose its power. The discussion around the shield is part of a growing movement for the decolonisation of museums in the UK and around the world.

Return of spears

Three of the spears were sent from Cambridge to the National Museum of Australia for the exhibition entitled ''Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians'', from 2 June 2020 to 26 April 2021. The La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council and La Perouse Aboriginal Community Alliance worked with the Cambridge museum towards repatriation of the three spears, and on 30 April 2021 it was announced that plans had been made to return the spears to Country.Notable people

* Biddy Giles, or ''Biyarrung'', (b.1820-died ca 1890s) was a Gweagal woman who lived throughout her life on traditional Gweagal land, and frequently impressed whites who employed her as a guide by her profound knowledge of the botany and landscape. She was a fluent Dharawal speaker. * Rodney Kelly (born 1977) is a Gweagal activist campaigning for the return of a shield held by the British Museum, as well as other Indigenous Australian artefacts in museums across Europe and Australia.See also

* Eora *Repatriation (cultural heritage)

Repatriation is the return of the cultural property, often referring to ancient or looted art, to their country of origin or former owners (or their heirs). The disputed cultural property items are physical artifacts of a group or society taken b ...

* Tharawal

The Dharawal people, also spelt Tharawal and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people, identified by the Dharawal language. Traditionally, they lived as hunter–fisher–gatherers in family groups or clans with ties of kinship, s ...

* Australian Aboriginal artefacts

Australian Aboriginal artefacts include a variety of cultural artefacts used by Aboriginal Australians. Most Aboriginal artefacts were multi-purpose and could be used for a variety of different occupations. Spears, clubs, boomerangs and shields ...

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Article by Keenahere

*

Trove

an

Worldcat

entries) {{Authority control Aboriginal peoples of New South Wales Artefacts from Africa, Oceania and the Americas in the British Museum James Cook Kurnell Peninsula