Guy Banister on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Guy Banister (March 7, 1901 – June 6, 1964) was an employee of the

House Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 12, p. 110. In June 1960, Banister moved his office to 531 Lafayette Street on the ground floor of the Newman Building. Around the corner but located in the same building, with a different entrance, was the address 544 Camp Street, which would later be found stamped on Banister was implicated in a 1961 raid on a munitions depot in Houma, Louisiana, in which "various weapons, grenades and ammunition were stolen ... which were reportedly seen stacked in Banister's back room by several witnesses." The ''

Banister was implicated in a 1961 raid on a munitions depot in Houma, Louisiana, in which "various weapons, grenades and ammunition were stolen ... which were reportedly seen stacked in Banister's back room by several witnesses." The ''

House Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 12, p. 111. Banister served as a character witness for Ferrie at his airline pilot's grievance board hearing in the summer of 1963.

Who was Guy Banister?

at www.jfk-online.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Banister, Guy 1901 births 1964 deaths People from Monroe, Louisiana John Birch Society members People associated with the assassination of John F. Kennedy Federal Bureau of Investigation agents Private detectives and investigators New Orleans Police Department officers Louisiana Democrats Deaths from coronary thrombosis

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

, an Assistant Superintendent of the New Orleans Police Department, and a private investigator. After his death, New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

District Attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a l ...

Jim Garrison

James Carothers Garrison (born Earling Carothers Garrison; November 20, 1921 – October 21, 1992) was the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, from 1962 to 1973. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he ...

alleged that he had been involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 12:30 p.m. CST in Dallas, Texas, while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza. Kennedy was in the vehicle with ...

.

He was an avid anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

, alleged member of the Minutemen

Minutemen were members of the organized New England colonial militia companies trained in weaponry, tactics, and military strategies during the American Revolutionary War. They were known for being ready at a minute's notice, hence the name. Mi ...

, the John Birch Society

The John Birch Society (JBS) is an American right-wing political advocacy group. Founded in 1958, it is anti-communist, supports social conservatism, and is associated with ultraconservative, radical right, far-right, or libertarian ideas.

T ...

, Louisiana Committee on Un-American Activities, and alleged publisher of the '' Louisiana Intelligence Digest''. He also supported anti-Castro

Castro is a Romance language word that originally derived from Latin ''castrum'', a pre-Roman military camp or fortification (cf: Greek: ''kastron''; Proto-Celtic:''*Kassrik;'' br, kaer, *kastro). The English-language equivalent is '' chester''.

...

groups in the New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

area: " Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front"; " Anti-Communist League of the Caribbean"; "Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Friends of Democratic Cuba

Friends of Democratic Cuba was formed on January 6, 1961

JFK Lancer to serve as the fund-raising arm of anti-Castro activi ...

". According to the ''JFK Lancer to serve as the fund-raising arm of anti-Castro activi ...

New Orleans States-Item

''The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate'' is an American newspaper published in New Orleans, Louisiana, since January 25, 1837. The current publication is the result of the 2019 acquisition of ''The Times-Picayune'' (itself a result of th ...

'' newspaper, Banister "participated in every anti-Communist South and Central American revolution that came along, acting as a key liaison man for the U.S. government-sponsored anti-Communist activities in Latin America."

Early life

Banister was born inMonroe, Louisiana

Monroe (historically french: Poste-du-Ouachita) is the eighth-largest city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, and parish seat of Ouachita Parish. With a 2020 census-tabulated population of 47,702, it is the principal city of the Monroe metropolita ...

, the oldest of seven children. After studying at the Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 nea ...

, he joined the Monroe Police Department.

Law enforcement career

In 1934, Banister joined theFederal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

. He was present at the killing of John Dillinger

John Herbert Dillinger (June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934) was an American gangster during the Great Depression. He led the Dillinger Gang, which was accused of robbing 24 banks and four police stations. Dillinger was imprisoned several times and ...

. Originally based in Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, he later moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

where he was involved in the investigation of the American Communist Party

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

was impressed by Banister's work and, in 1938, he was promoted to run the FBI unit in Butte, Montana

Butte ( ) is a consolidated city-county and the county seat of Silver Bow County, Montana, United States. In 1977, the city and county governments consolidated to form the sole entity of Butte-Silver Bow. The city covers , and, according to the ...

. He also served in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat of Oklahoma County, it ranks 20th among United States cities in population, a ...

, Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. In Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, he was the Special Agent in Charge for the FBI. He retired from the FBI in 1954.

Banister moved to Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and, in January 1955, became Assistant Superintendent of the New Orleans Police Department

The New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) has primary responsibility for law enforcement in New Orleans, Louisiana. The department's jurisdiction covers all of Orleans Parish, while the city is divided into eight police districts.

The NOPD has a ...

, where he was given the task of investigating organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

and corruption within the police force. It later emerged that he was also involved in looking at the role that left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

political activists were playing in the struggle for civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

. On the campuses of Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Tulane University

Tulane University, officially the Tulane University of Louisiana, is a private university, private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by seven young medical doctors, it turned into ...

and Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 nea ...

, he ran a network of informants collecting information on "communist" activities. He submitted reports on his findings to the FBI through contacts.

In March 1957, NOPD Superintendent Provosty Dayries suspended Banister after witnesses reported he had drawn his revolver while threatening a bartender at the Old Absinthe House on Bourbon Street

Bourbon Street (french: Rue Bourbon, es, Calle de Borbón) is a historic street in the heart of the French Quarter of New Orleans. Extending thirteen blocks from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue, Bourbon Street is famous for its many bars an ...

in the French Quarter

The French Quarter, also known as the , is the oldest neighborhood in the city of New Orleans. After New Orleans (french: La Nouvelle-Orléans) was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city developed around the ("Old Squ ...

. Banister denied the allegations, and the bartender described the incident as an "unprovoked attack". Banister's suspension ended in June of that year, however, Dayries dismissed Banister from the force for "open defiance" after he refused to be reassigned as the department's chief of planning. In supporting Dayries' decision, New Orleans' mayor Chep Morrison

deLesseps Story Morrison Sr., also known as Chep Morrison (January 18, 1912 – May 22, 1964), was an American attorney and politician who was the 54th mayor of New Orleans, Louisiana, from 1946 to 1961. He then served as an appointee of U.S. ...

said that there was "no other course that one could sensibly follow".

Private investigation, Cuba, Oswald, Marcello

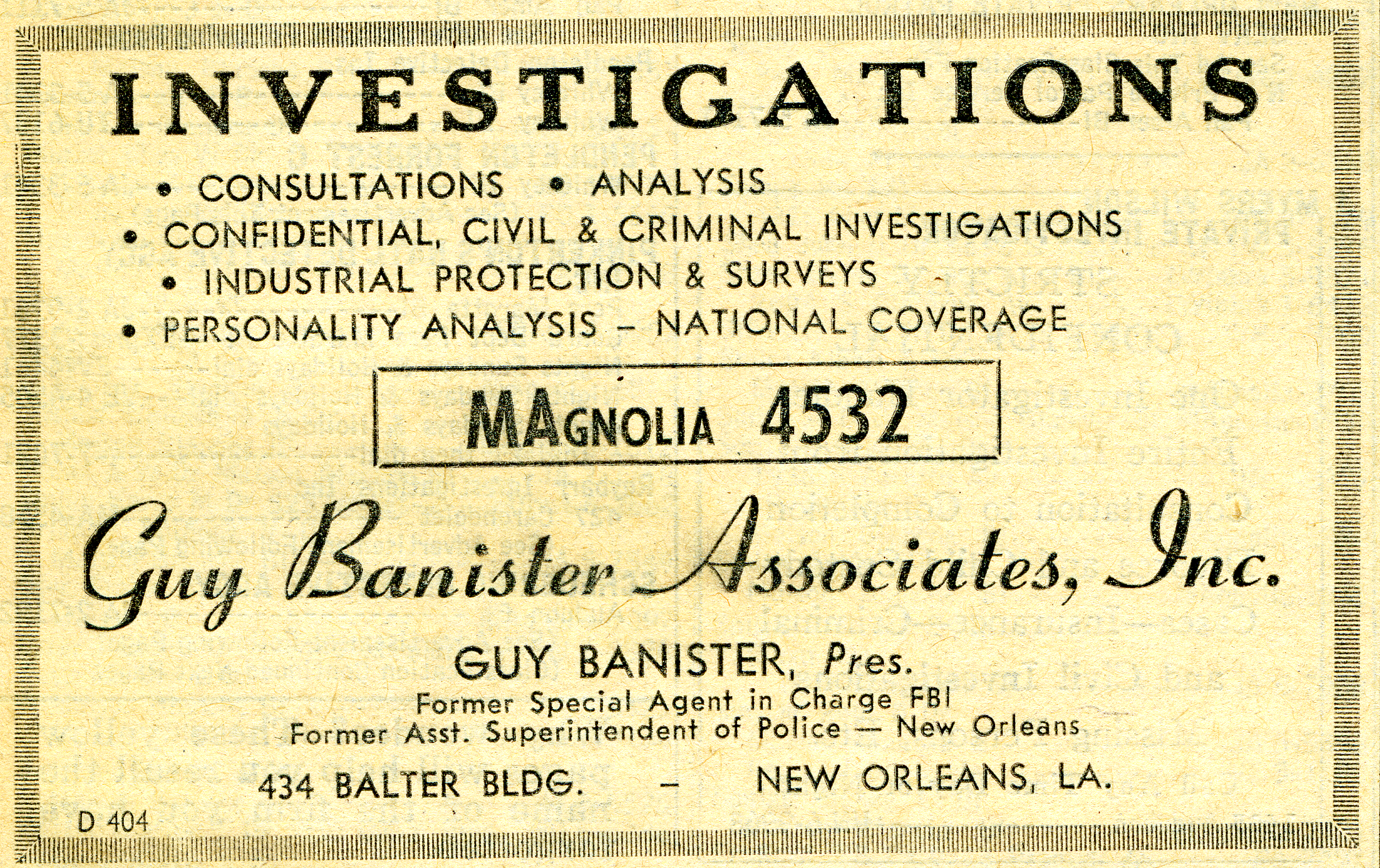

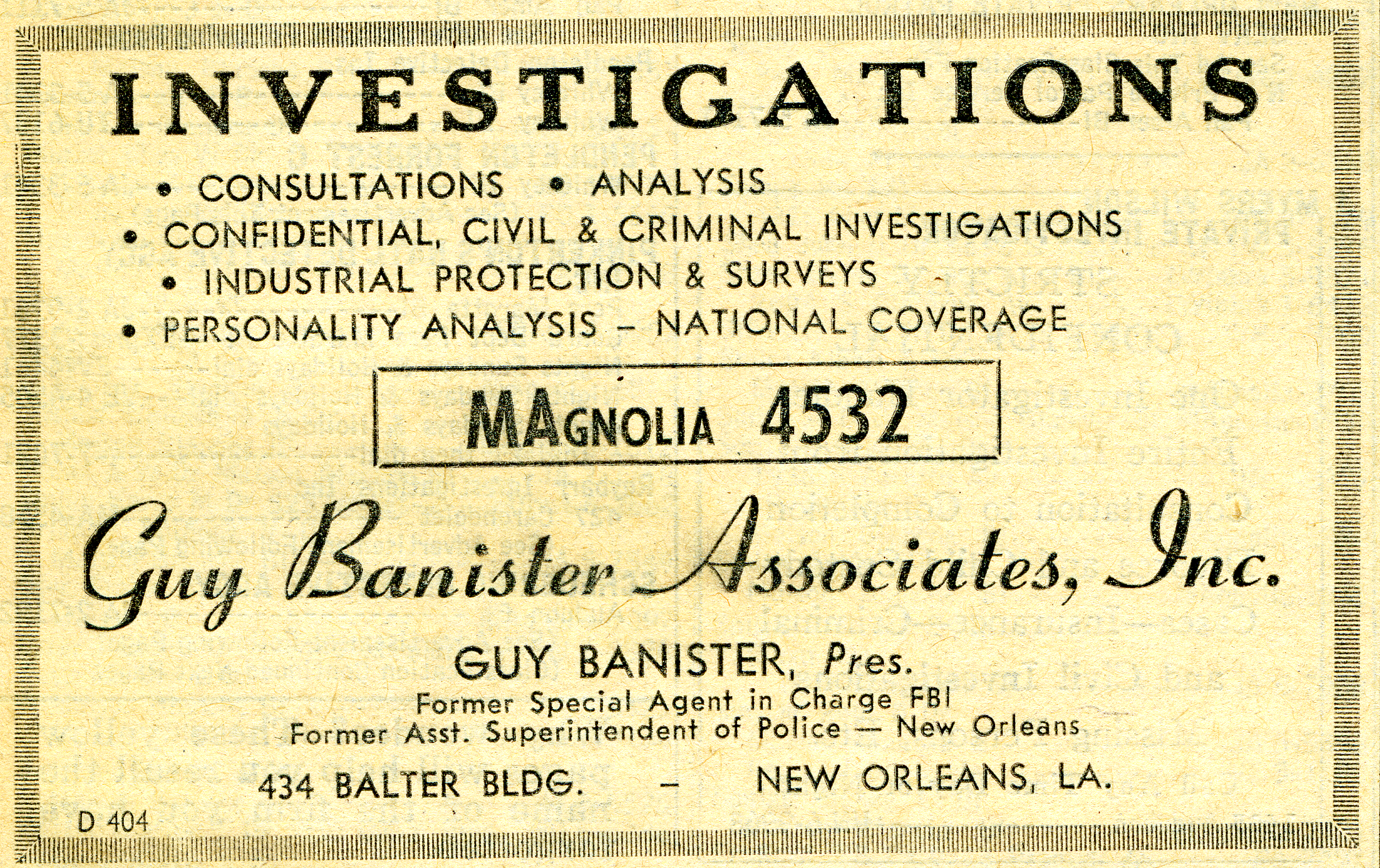

After leaving the New Orleans Police Department, Banister established his ownprivate detective

A private investigator (often abbreviated to PI and informally called a private eye), a private detective, or inquiry agent is a person who can be hired by individuals or groups to undertake investigatory law services. Private investigators of ...

agency, Guy Banister Associates, Inc. at 434 Balter Building.David FerrieHouse Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 12, p. 110. In June 1960, Banister moved his office to 531 Lafayette Street on the ground floor of the Newman Building. Around the corner but located in the same building, with a different entrance, was the address 544 Camp Street, which would later be found stamped on

Fair Play for Cuba Committee The Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC) was an activist group set up in New York City by Robert Taber in April 1960.

History

The FPCC's purpose was to provide grassroots support for the Cuban Revolution against attacks by the United States govern ...

leaflets distributed by Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at the age of 12 fo ...

, the suspected assassin of President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

. The Newman Building housed militant anti-Castro groups, including the Cuban Revolutionary Council

The Cuban Revolutionary Council (CRC) was a group formed, with CIA assistance, three weeks before the April 17, 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion to "coordinate and direct" the activities of another group known as the Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front ...

(October 1961 to February 1962), as well as Sergio Arcacha Smith's Crusade to Free Cuba Committee. Banister was implicated in a 1961 raid on a munitions depot in Houma, Louisiana, in which "various weapons, grenades and ammunition were stolen ... which were reportedly seen stacked in Banister's back room by several witnesses." The ''

Banister was implicated in a 1961 raid on a munitions depot in Houma, Louisiana, in which "various weapons, grenades and ammunition were stolen ... which were reportedly seen stacked in Banister's back room by several witnesses." The ''New Orleans States-Item

''The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate'' is an American newspaper published in New Orleans, Louisiana, since January 25, 1837. The current publication is the result of the 2019 acquisition of ''The Times-Picayune'' (itself a result of th ...

'' newspaper reported an allegation that Banister served as a munitions supplier for the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fina ...

and continued to deal weapons from his office until 1963.

In 1962, Banister allegedly dispatched an associate, Maurice Brooks Gatlin — legal counsel of Banister's " Anti-Communist League of the Caribbean" — to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

to deliver a suitcase containing $200,000 for the French OAS. In 1963, Banister and anti-Castro activist David Ferrie

David William Ferrie (March 28, 1918 – February 22, 1967) was an American pilot who was alleged by New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison to have been involved in a conspiracy to assassinate President John F. Kennedy. Garrison also alle ...

began working for a lawyer named G. Wray Gill and his client, New Orleans Mafia boss Carlos Marcello

Carlos Joseph Marcello (; born Calogero Minacore ; February 6, 1910 – March 3, 1993) was an Italian-American crime boss of the New Orleans crime family from 1947 until the late 1980s.

Aside from his role in the American Mafia, he is also n ...

. This involved attempts to block Marcello's deportation to Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by H ...

.

In early 1962, Banister assisted David Ferrie in a dispute with Eastern Airlines regarding charges brought against Ferrie by the airline and New Orleans police of "crimes against nature

The crime against nature or unnatural act has historically been a legal term in English-speaking states identifying forms of sexual behavior not considered natural or decent and are legally punishable offenses. Sexual practices that have histor ...

and extortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence; the bulk of this article deals with such cases. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, ...

." During this period, Ferrie was frequently seen at Banister's office.David FerrieHouse Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 12, p. 111. Banister served as a character witness for Ferrie at his airline pilot's grievance board hearing in the summer of 1963.

JFK assassination and trial of Clay Shaw

On the afternoon of November 22, 1963, the day that PresidentJohn F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

was assassinated, Banister and one of his investigators, Jack Martin, were drinking together at the Katzenjammer Bar, located next door to 544 Camp Street in New Orleans. On their return to Banister's office, the two men got into a dispute. Banister believed that Martin had stolen some files and drew his .357 Magnum revolver, striking Martin with it several times. Martin was badly injured and treated at Charity Hospital

Charity may refer to:

Giving

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sharing

* Ch ...

. When questioned about the incident in December 1977 by investigators for the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations

The United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was established in 1976 to investigate the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963 and 1968, respectively. The HSCA completed its i ...

(HSCA), Martin said that in the heat of the argument just prior to the pistol-whipping he had said to Banister: "What are you going to do — kill me like you all did Kennedy?"

Over the next few days, Martin told authorities and reporters that anti-Castro activist David Ferrie

David William Ferrie (March 28, 1918 – February 22, 1967) was an American pilot who was alleged by New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison to have been involved in a conspiracy to assassinate President John F. Kennedy. Garrison also alle ...

had been involved in the assassination. He claimed that Ferrie knew Oswald from their days in the New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Civil Air Patrol

Civil Air Patrol (CAP) is a congressionally chartered, federally supported non-profit corporation that serves as the official civilian auxiliary of the United States Air Force (USAF). CAP is a volunteer organization with an aviation-minded mem ...

, and that Ferrie might have taught Oswald how to use a rifle with a telescopic sight. Martin also claimed that Ferrie drove to Texas on the day of Kennedy's assassination, to serve as a getaway pilot for the assassins.

Witnesses interviewed by the HSCA indicate Banister was "aware of Oswald and his Fair Play for Cuba Committee The Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC) was an activist group set up in New York City by Robert Taber in April 1960.

History

The FPCC's purpose was to provide grassroots support for the Cuban Revolution against attacks by the United States govern ...

before the assassination."

Banister's secretary, Delphine Roberts, told author Anthony Summers

Anthony Bruce Summers (born 21 December 1942) is an Irish author. He is a Pulitzer Prize Finalist and has written ten non-fiction books.

Career

Summers is an Irish citizen who has been working with Robbyn Swan for more than thirty years befor ...

that Oswald "seemed to be on familiar terms with Banister and with anister'soffice." Roberts said, "As I understood it, he had the use of an office on the second floor, above the main office where we worked. Then, several times, Mr. Banister brought me upstairs, and in the office above I saw various writings stuck up on the wall pertaining to Cuba. There were various leaflets up there pertaining to Fair Play for Cuba.'" The House Select Committee on Assassinations investigated Roberts' claims and said that "the reliability of her statements could not be determined."

The alleged activities of Banister, Ferrie and Oswald reached New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison

James Carothers Garrison (born Earling Carothers Garrison; November 20, 1921 – October 21, 1992) was the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, from 1962 to 1973. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he ...

who, by late 1966, had become interested in the New Orleans aspects of the assassination. In December 1966, Garrison interviewed Martin about these activities. Martin claimed that Banister, Ferrie and a group of anti-Castro Cuban exiles were involved in operations against Castro's Cuba that included gun running and burglarized armories.

As Garrison continued his investigation, he became convinced that a group of right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authorit ...

activists, including Banister, Ferrie and Clay Shaw

Clay LaVergne Shaw (March 17, 1913 – August 15, 1974) was an American businessman and military officer from New Orleans, Louisiana. Shaw is best known for being the only person brought to trial for involvement in the assassination of John F. ...

, were involved in a conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agree ...

with elements of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) to kill Kennedy. Garrison would later claim that the motive for the assassination was anger over Kennedy's attempts to obtain a peace settlement in both Cuba and Vietnam. Garrison also believed that Banister, Shaw, and Ferrie had conspired to set up Oswald as a patsy in the JFK assassination.

Post JFK

Banister's publication, the ''Louisiana Intelligence Digest'', maintained that the civil rights movement was part of an international communist conspiracy and wastreason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

ous.

Personal life

Banister was aFreemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and a Shriner

Shriners International, formally known as the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (AAONMS), is an American Masonic society established in 1870 and is headquartered in Tampa, Florida.

Shriners International describes itself ...

.

Death

Banister died ofcoronary thrombosis

Coronary thrombosis is defined as the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. This blood clot may then restrict blood flow within the heart, leading to heart tissue damage, or a myocardial infarction, also known as a heart at ...

on June 6, 1964. Banister's files went to various people after his death. Later, New Orleans Assistant District Attorney Andrew Sciambra interviewed Banister's widow. She told him that she saw some Fair Play for Cuba leaflets in Banister's office when she went there after his death.New Orleans District Attorney's Office, interview of Mrs. Mary Banister by Andrew Sciambra, April 29–30, 1967.

Fictional portrayals

Banister is a character inOliver Stone

William Oliver Stone (born September 15, 1946) is an American film director, producer, and screenwriter. Stone won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay as writer of '' Midnight Express'' (1978), and wrote the gangster film remake '' Sc ...

's 1991 movie ''JFK

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

'', in which he is portrayed by Edward Asner

Eddie Asner (; November 15, 1929 – August 29, 2021) was an American actor and former president of the Screen Actors Guild. He is best remembered for portraying Lou Grant during the 1970s and early 1980s, on both ''The Mary Tyler Moore Show'' an ...

. He is also central to the plot of Don DeLillo

Donald Richard DeLillo (born November 20, 1936) is an American novelist, short story writer, playwright, screenwriter and essayist. His works have covered subjects as diverse as television, nuclear war, sports, the complexities of language, per ...

's novel ''Libra

Libra generally refers to:

* Libra (constellation), a constellation

* Libra (astrology), an astrological sign based on the star constellation

Libra may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Libra'' (novel), a 1988 novel by Don DeLillo

Musi ...

''. Guy Banister appears as a character in James Ellroy

Lee Earle "James" Ellroy (born March 4, 1948) is an American crime fiction writer and essayist. Ellroy has become known for a telegrammatic prose style in his most recent work, wherein he frequently omits connecting words and uses only short, sta ...

's 1995 novel ''American Tabloid

''American Tabloid'' is a 1995 novel by James Ellroy that chronicles the events surrounding three rogue American law enforcement officers from November 22, 1958, through November 22, 1963. Each becomes entangled in a web of interconnecting associ ...

'' and its sequel ''The Cold Six Thousand

''The Cold Six Thousand'' is a 2001 crime fiction novel by James Ellroy. It is the first sequel to ''American Tabloid'' in the Underworld USA Trilogy and continues many of the earlier novel's characters and plotlines. Specifically, it follows thr ...

''. In ''American Tabloid'', Banister organizes John Kennedy's assassination, which is based on Ward Littell's original plan. Littell is one of the story's main characters. In ''The Cold Six Thousand'', Guy Banister is murdered by Chuck Rogers under orders from Carlos Marcello

Carlos Joseph Marcello (; born Calogero Minacore ; February 6, 1910 – March 3, 1993) was an Italian-American crime boss of the New Orleans crime family from 1947 until the late 1980s.

Aside from his role in the American Mafia, he is also n ...

.

References

External links

*Who was Guy Banister?

at www.jfk-online.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Banister, Guy 1901 births 1964 deaths People from Monroe, Louisiana John Birch Society members People associated with the assassination of John F. Kennedy Federal Bureau of Investigation agents Private detectives and investigators New Orleans Police Department officers Louisiana Democrats Deaths from coronary thrombosis