Gustav Krupp Von Bohlen Und Halbach on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gustav Georg Friedrich Maria Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (born Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach; 7 August 1870 – 16 January 1950) was a German foreign service official who became chairman of the board of

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was born Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach in

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was born Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach in

By

By

During the

During the

Friedrich Krupp AG

The Krupp family (see #Pronunciation, pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (F ...

, a heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

conglomerate, after his marriage to Bertha Krupp

Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (29 March 1886 – 21 September 1957) was a member of the Krupp family, Germany's leading industrial dynasty of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the elder child and heir of Friedrich Alfred Krupp she was the ...

, who had inherited the company. He and his son Alfried would lead the company through two world wars, producing almost everything for the German war machine from U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s, battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s, howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s, trains, railway gun

A railway gun, also called a railroad gun, is a large artillery piece, often surplus naval artillery, mounted on, transported by, and fired from a specially designed railroad car, railway wagon. Many countries have built railway guns, but the ...

s, machine guns, cars, tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s, and much more. Krupp produced the Tiger I

The Tiger I () was a German heavy tank of World War II that operated beginning in 1942 in Africa and in the Soviet Union, usually in independent heavy tank battalions. It gave the German Army its first armoured fighting vehicle that mounted ...

tank, Big Bertha and the Paris Gun

The Paris Gun (german: Paris-Geschütz / Pariser Kanone) was the name given to a type of German long-range siege gun, several of which were used to bombard Paris during World War I. They were in service from March to August 1918. When the guns w ...

, among other inventions, under Gustav. Following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, plans to prosecute him as a war criminal at the 1945 Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

were dropped because by then he was bedridden, senile, and considered medically unfit for trial. The charges against him were held in abeyance in case he were found fit for trial.

Early life

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was born Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach in

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was born Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

in 1870. He was a grandson of Henry Bohlen

Henry Bohlen (October 22, 1810 – August 22, 1862) was a German-American Union Brigadier General of the American Civil War. Before becoming the first foreign-born Union general in the Civil War, he fought in the Mexican-American War (on the U.S. ...

and related to Charles E. Bohlen

Charles "Chip" Eustis Bohlen (August 30, 1904 – January 1, 1974) was an American diplomat, ambassador, and expert on the Soviet Union. He helped shape US foreign policy during World War II and the Cold War and helped develop the Marshall Plan ...

and Karoline of Wartensleben

Countess Karoline Friederike Cäcilie Klothilde von Wartensleben (6 April 1844 in Mannheim – 10 July 1905 in Detmold) was a German noblewoman. She is a paternal great-great-grandmother of King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands.

Early life ...

. He married Bertha Krupp

Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (29 March 1886 – 21 September 1957) was a member of the Krupp family, Germany's leading industrial dynasty of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the elder child and heir of Friedrich Alfred Krupp she was the ...

in October 1906. Bertha had inherited her family's company in 1902 at age 16 after the death of her father, Friedrich Alfred Krupp

Friedrich Alfred Krupp (17 February 1854 – 22 November 1902) was a German steel manufacturer and head of the company Krupp. He was the son of Alfred Krupp and inherited the family business when his father died in 1887. Whereas his father had ...

. German Emperor Kaiser William II personally led a search for a suitable spouse for Bertha, as the Krupp empire could not be headed by a woman. Gustav was picked from his previous post at the Vatican. The Kaiser announced at the wedding that Gustav would be allowed to add the Krupp name to his own. Gustav became company chairman in 1909.

After 1910, the Krupp company became a member and major funder of the Pan-German League

The Pan-German League (german: Alldeutscher Verband) was a Pan-German nationalist organization which was officially founded in 1891, a year after the Zanzibar Treaty was signed.

Primarily dedicated to the German Question of the time, it held pos ...

(Alldeutscher Verband) which mobilised popular support in favour of two army bills, in 1912 and 1913, to raise Germany's standing army to 738,000 men.

World War I

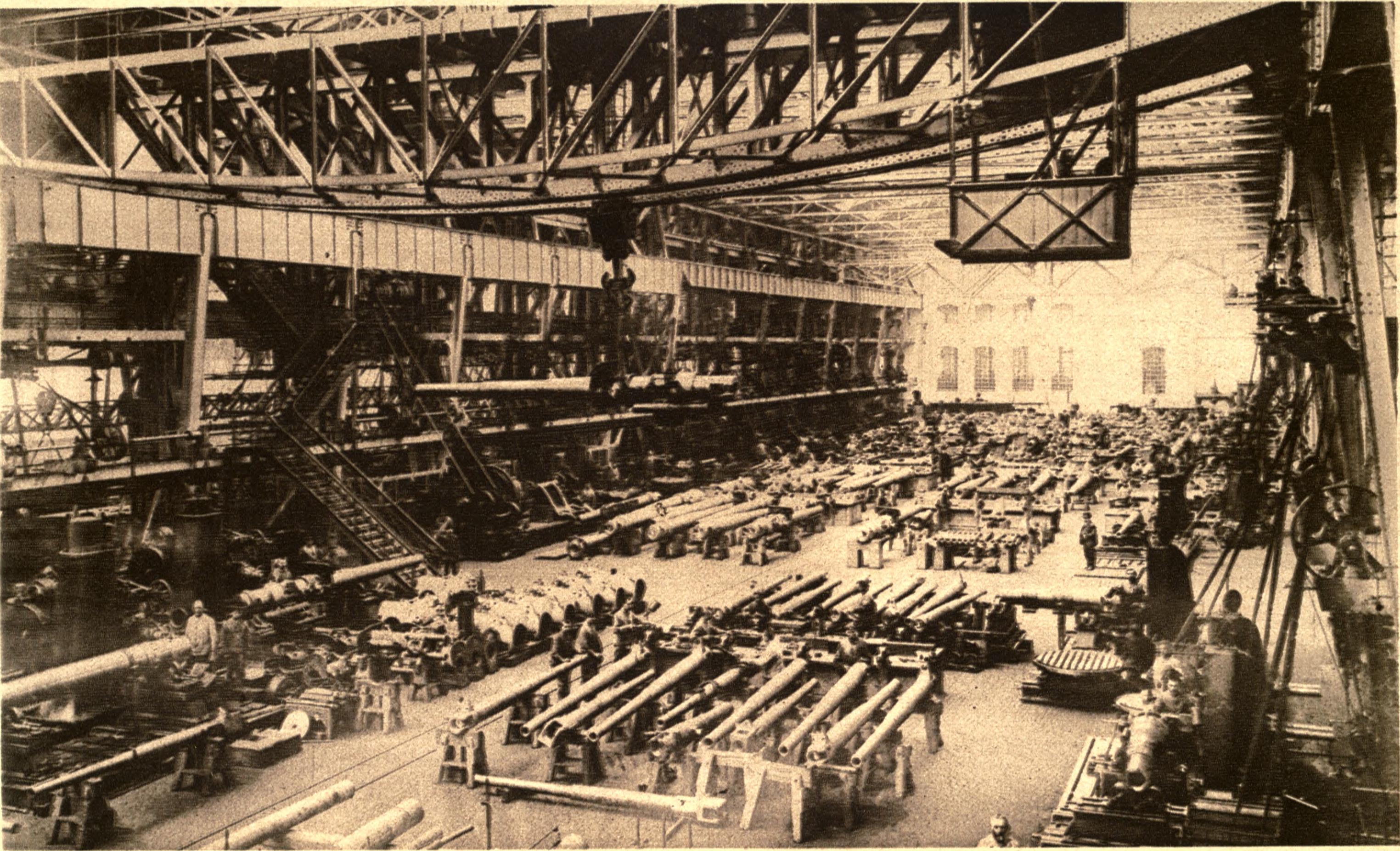

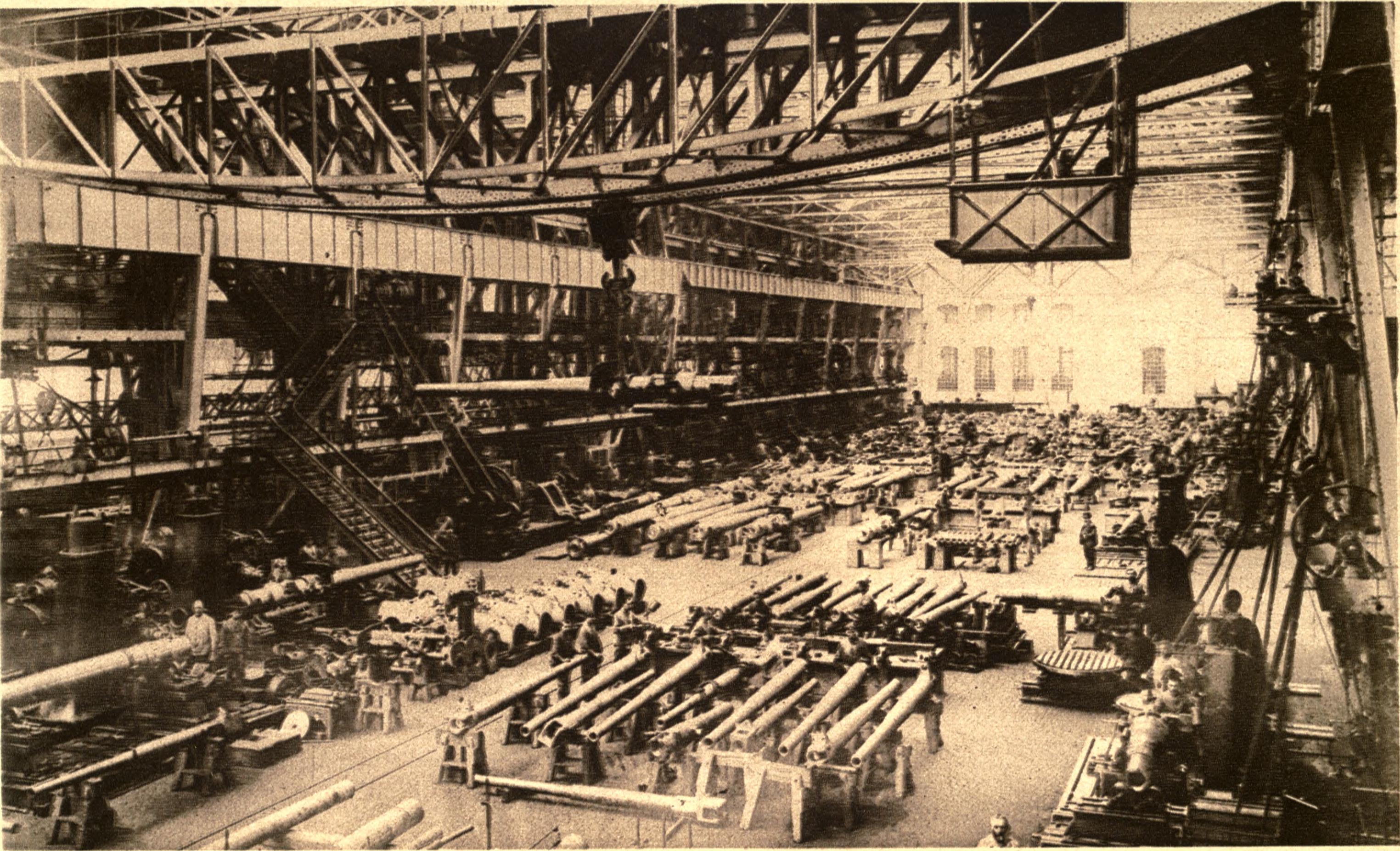

By

By World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the company had a near monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

in heavy arms manufacture in Germany. At the start of the war, the company lost access to most of its overseas markets, but this was more than offset by increased demand for weapons by Germany and her allies (Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

). In 1902, before Krupp's marriage, the company leased a fuse

Fuse or FUSE may refer to:

Devices

* Fuse (electrical), a device used in electrical systems to protect against excessive current

** Fuse (automotive), a class of fuses for vehicles

* Fuse (hydraulic), a device used in hydraulic systems to protect ...

patent to Vickers Limited

Vickers Limited was a British engineering conglomerate. The business began in Sheffield in 1828 as a steel foundry and became known for its church bells, going on to make shafts and propellers for ships, armour plate and then artillery. Entir ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. Among the company's products was a 94-ton howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

named Big Bertha, after Krupp's wife, and the Paris Gun

The Paris Gun (german: Paris-Geschütz / Pariser Kanone) was the name given to a type of German long-range siege gun, several of which were used to bombard Paris during World War I. They were in service from March to August 1918. When the guns w ...

. Gustav also won the lucrative contract for Germany's U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s, which were built at the family's shipyard in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

. Krupp's estate, the Villa Hügel, had a suite of rooms for Wilhelm II whenever he came to visit.

Interwar years

During the

During the occupation of the Ruhr

The Occupation of the Ruhr (german: link=no, Ruhrbesetzung) was a period of military occupation of the Ruhr region of Germany by France and Belgium between 11 January 1923 and 25 August 1925.

France and Belgium occupied the heavily industria ...

in 1923, a French military court had Krupp imprisoned for seven months until the German government stopped their politics of passive resistance.

The Versailles Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

prevented Germany from making armaments and submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, forcing Krupp to significantly reduce his labour force. His company diversified to agricultural equipment, vehicles and consumer goods. However, using the profits from the Vickers patent deal and subsidies from the Weimar government

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

, Krupp secretly began the rearming of Germany with the ink barely dry on the treaty of Versailles. It secretly continued to work on artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

through subsidiaries in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, and built submarine pens in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. In the 1930s, it restarted manufacture of tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s such as the Tiger I

The Tiger I () was a German heavy tank of World War II that operated beginning in 1942 in Africa and in the Soviet Union, usually in independent heavy tank battalions. It gave the German Army its first armoured fighting vehicle that mounted ...

and other war materials, again using foreign subsidiaries.

Krupp was a member of the Prussian State Council

The Prussian State Council (german: Preußischer Staatsrat) was the upper chamber of the bicameral legislature of the Free State of Prussia between 1920 and 1933. The lower chamber was the Prussian Landtag (''Preußischer Landtag'').

Implementa ...

from 1921 to 1933. Krupp was an avowed monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

, but his first loyalty was to whoever held power. He once left a business meeting in disgust when another industrialist, who was the one hosting the meeting, referred to the late President Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first President of Germany (1919–1945), president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Eber ...

as "that saddlemaker" ''(Der Sattelhersteller)''.

Krupp initially opposed the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

, yet at the secret meeting with Adolf Hitler and leading German industrialists on February 20, 1933, he contributed one million Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reich ...

to the Nazi party's fund for the March 1933 election, which enabled Hitler to take control of the government. After Hitler won power, Krupp became, as Fritz Thyssen

Friedrich "Fritz" Thyssen (9 November 1873 – 8 February 1951) was a German businessman, born into one of Germany's leading industrial families. He was an early supporter of the Nazi Party, but later broke with them.

Biography

Youth

Thyssen w ...

later put it, "a super Nazi", and contributed to the Adolf Hitler Fund of German Trade and Industry The Adolf Hitler Fund of German Trade and Industry (''"Adolf-Hitler-Spende der deutschen Wirtschaft"'') was a donation from the German employers' association and the ''"Reichsverband"'' of German industry, which was established on June 1, 1933, to s ...

which was established in June 1933 to support the NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

. As president of the ''Reichsverband'' of German industry he led the effort to expel its Jewish members.

Like many German nationalists, Krupp believed that the Nazis could be used to end the Republic, and then be pushed aside to restore the Kaiser and the old elites. When all parties were abolished and civil liberties suspended following the Reichstag fire and Hitler's grab for absolute power, Krupp found that he and the rest of the old elites were in the grip of the Party; the movement they had hoped to ride back into power upon had instead ridden them. Always flexible, Krupp cooperated with the new dictatorship.

Hitler had tried to gain entry to the Krupp factories in 1929, but was rebuffed because Krupp felt he would see some of the secret armament work there and reveal it to the world. Bertha Krupp never liked Hitler even though she never complained when the company's bottom line rose through the armaments contracts and production. She referred to him as "that certain gentleman" ''(Dieser gewisse Herr)'' and pleaded illness when Hitler came on an official tour in 1934. Her daughter Irmgard acted as hostess.Manchester, William. ''The Arms of Krupp''. Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1968.

World War II

Krupp suffered failing health from 1939 onwards, and astroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

left him partially paralysed

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

in 1941. He became a figurehead until he formally handed over the running of the business to his son Alfried in 1943. Krupp industries, under both his leadership and later that of his son, was offered facilities in eastern Europe and made extensive use of forced labor during the war.

On 25 July 1943 the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

attacked the Krupp Works with 627 heavy bombers, dropping 2,032 long tons of bombs in an Oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

-marked attack. Upon his arrival at the works the next morning, Krupp suffered a fit from which he never recovered.

Nuremberg Trials

Following the Allied victory, plans to prosecute Gustav Krupp as a war criminal at the 1945Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

were dropped because by then he was bedridden and senile. Despite his personal absence from the prisoners' dock, however, Krupp remained technically still under indictment and liable to prosecution in subsequent proceedings.

Death

He died at his residence nearWerfen

Werfen () is a market town in the district of St. Johann im Pongau, in the Austrian state of Salzburg. It is mainly known for medieval Hohenwerfen Castle and the Eisriesenwelt ice cave, the largest in the world.

Geography

Werfen is located in the ...

, Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian) is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the ...

in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

on 16 January 1950. His widow died in 1957. He had eight children including Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (1907–1967), the last owner of Krupp (succeeded by his Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation

__NOTOC__

The Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation (german: Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung) is a major German philanthropic foundation, created by and named in honor of Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, former owner ...

).

See also

*Secret Meeting of 20 February 1933

The Secret Meeting of 20 February 1933 (german: Geheimtreffen vom 20. Februar 1933) was a secret meeting held by Adolf Hitler and 20 to 25 industrialists at the official residence of the President of the Reichstag Hermann Göring in Berlin. Its pu ...

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Krupp Von Bohlen Und Halbach, Gustav 1870 births 1950 deaths Businesspeople from The HagueGustav

Gustav, Gustaf or Gustave may refer to:

*Gustav (name), a male given name of Old Swedish origin

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''Primeval'' (film), a 2007 American horror film

* ''Gustav'' (film series), a Hungarian series of animated short cart ...

German steel industry businesspeople

German industrialists

German untitled nobility

German monarchists

German nationalists

German people of World War II

Members of the Prussian House of Lords

Recipients of the Order of St. Sava

Heidelberg University alumni

Nazis

German fascists

People declared mentally unfit for court