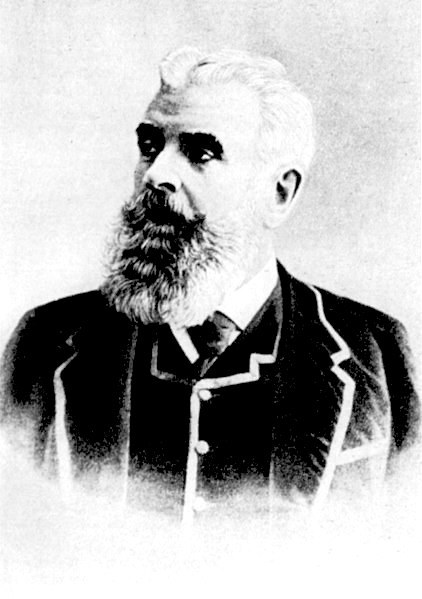

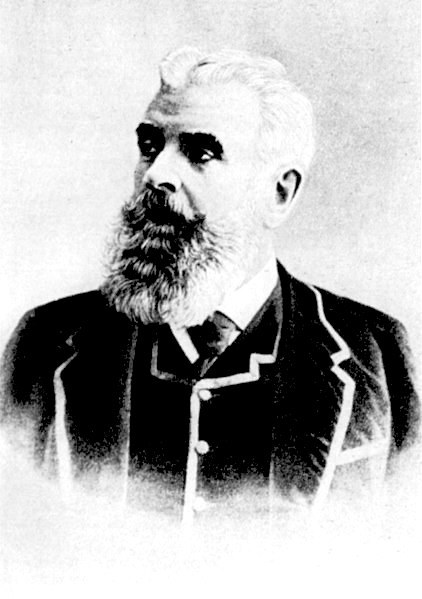

Guido Henckel Von Donnersmarck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Guido Georg Friedrich Erdmann Heinrich Adalbert Graf Henckel von Donnersmarck, from 1901 Prince (''Fürst'') Henckel von Donnersmarck (born 10 August 1830 in Breslau, died 19 December 1916 in Berlin) was a German

Guido Georg Friedrich Erdmann Heinrich Adalbert Graf Henckel von Donnersmarck, from 1901 Prince (''Fürst'') Henckel von Donnersmarck (born 10 August 1830 in Breslau, died 19 December 1916 in Berlin) was a German

Guido Georg Friedrich Erdmann Heinrich Adalbert Graf Henckel von Donnersmarck, from 1901 Prince (''Fürst'') Henckel von Donnersmarck (born 10 August 1830 in Breslau, died 19 December 1916 in Berlin) was a German

Guido Georg Friedrich Erdmann Heinrich Adalbert Graf Henckel von Donnersmarck, from 1901 Prince (''Fürst'') Henckel von Donnersmarck (born 10 August 1830 in Breslau, died 19 December 1916 in Berlin) was a German nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

, industrial magnate, member of the House of Henckel von Donnersmarck and one of the richest men of his time. He was married in his first marriage to the famed French courtesan Esther Lachmann, known as La Païva, of Russian Jewish origin.

Career

Born in Breslau,Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

, he was the son of Karl Lazarus, Count Henckel von Donnersmarck (1772–1864) and his wife Julie, née Countess von Bohlen

Bohlen is a surname shared by several notable people, among them being:

;Bohlen

* Avis Bohlen (born 1940), American diplomatDaughter of Charles E. Bohlen

* Charles E. Bohlen (1904–1974), American diplomat

* Dieter Bohlen (born 1954), German mu ...

(1800–1866). When his older brother Karl Lazarus Graf Henckel von Donnersmarck died in 1848, his father transferred his numerous mining properties and ironworks in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

to Guido, who soon became one of the richest men in Europe.

Henckel also had a sister, Wanda (1826–1907), who in 1843 became the second wife of Ludwig, Prince von Schönaich-Carolath. Friedrich von Holstein, Political Secretary to the German Foreign Office, claimed that the father of one of her sons was either a waiter or a coachman; "One must choose between the two," Holstein wrote.

Henckel lived in Paris from the late 1850s until 1877 with his mistress (later wife), Pauline Thérèse Lachmann, Marquise de Païva, known as La Païva, the most successful of 19th century French courtesan

Courtesan, in modern usage, is a euphemism for a "kept" mistress or prostitute, particularly one with wealthy, powerful, or influential clients. The term historically referred to a courtier, a person who attended the court of a monarch or other ...

s. He engaged in stock market speculations, and Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

sometimes found his shady contacts politically useful. In 1857, Henckel purchased for his mistress the Château de Pontchartrain

The Château de Pontchartrain is mainly in the municipality of Jouars-Pontchartrain within Yvelines, in the west of the Île de France region of France.

The west end of its domain (a throwback term for grounds equivalent to demesne: a personal es ...

in Seine-et-Oise

Seine-et-Oise () was the former department of France encompassing the western, northern and southern parts of the metropolitan area of Paris. English translation of the French edition of 1963, which was produced under the general direction of Pierre Levellois and Gaston d'Angelis.

Like many other Prussian business and political figures, Henckel was a reserve officer, and during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 he was military governor in

Handbuch über den Königlich Preußischen Hof und Staat

' (1908), Herrenhaus p. 218 ** Knight of the

Fürst Donnersmarck-Stiftung zu Berlin - Foundation for people with disabilities founded 1916 by Fürst von Donnersmarck

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henckel Von Donnersmarck, Guido 1830 births 1916 deaths German company founders German industrialists German landowners German mining businesspeople Members of the Prussian House of Lords

Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand Est ...

and erstwhile governor for the to-be-annexed Département de la Lorraine

Bezirk Lothringen (today's french: link=no, Présidence de la Lorraine, at the time translated into french: link=no, Département de la Lorraine i.e. Department of Lorraine), also called German Lorraine (''Deutsch Lothringen''), was a governmen ...

(1871–1872). During the negotiations for the French war indemnity

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

...

in 1871 he advised Bismarck that France could easily pay it - and indeed, the indemnity payments were completed ahead of schedule in 1873.

After Henckel's return to Germany with his wife in 1877, Bismarck occasionally entrusted him with discreet political or financial transactions. In 1884, for instance, Henckel arranged a loan for Bismarck's old friend, Prince Orlov, at that time the Russian ambassador in Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

.

Henckel maintained a well-stocked game preserve on his estate at Neudeck in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

. When Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Emp ...

visited Neudeck for a shoot in January 1890, he was able to kill 550 pheasants in a single day.

As an investor in the publishing company, in 1894 Henckel was unwillingly drawn into the dispute between the editor of Kladderadatsch

''Kladderadatsch'' (onomatopoeic for "Crash") was a satirical German-language magazine first published in Berlin on 7 May 1848. It appeared weekly or as the ''Kladderadatsch'' put it: "daily, except for weekdays." It was founded by Albert Hofmann ...

and ''Geheimrat'' Friedrich von Holstein of the Foreign Office. In a series of anonymous articles the journal had held up to ridicule Holstein, Alfred von Kiderlen-Wächter and Philipp zu Eulenburg. Kiderlen challenged the editor of ''Kladderadatsch'' to a duel and wounded him, but Holstein was not satisfied. He issued a similar challenge to Henckel, who maintained his innocence and declined to fight. Wilhelm II wisely refused to force Henckel to fight Holstein, for, years later, two junior officials of the Foreign Office asserted that they had been the authors of the ''Kladderadatsch'' articles.

Wilhelm II granted Henckel the title of '' Fürst'' in 1901. The same year he declined appointment as Prussian Minister of Finance upon the death of Johannes Miquel

Johannes is a Medieval Latin form of the personal name that usually appears as "John" in English language contexts. It is a variant of the Greek and Classical Latin variants (Ιωάννης, ''Ioannes''), itself derived from the Hebrew name '' Yeh ...

.

In the years preceding World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

Henckel was estimated to be the second-wealthiest German subject, his fortune exceeded only by that of Bertha Krupp

Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (29 March 1886 – 21 September 1957) was a member of the Krupp family, Germany's leading industrial dynasty of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the elder child and heir of Friedrich Alfred Krupp she was the ...

von Bohlen und Halbach.

In 1916 he founded the Fürst Donnersmarck Foundation in Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

with the donation of about of land and four million Goldmarks, an institution instituted to make scientific use of the experiences gained in World War I and to apply these insights in a therapeutic way, and now supporting the rehabilitation, care, and support of the physically and multiply disabled as well as research supporting that care.

Marriages

His first wife wasPauline Thérèse Lachmann Pauline may refer to:

Religion

*An adjective referring to St Paul the Apostle or a follower of his doctrines

*An adjective referring to St Paul of Thebes, also called St Paul the First Hermit

*An adjective referring to the Paulines, various relig ...

(b. Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, 7 May 1819 – d. Neudeck, 21 January 1884), a courtesan

Courtesan, in modern usage, is a euphemism for a "kept" mistress or prostitute, particularly one with wealthy, powerful, or influential clients. The term historically referred to a courtier, a person who attended the court of a monarch or other ...

better known as La Païva. They married in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

on 28 October 1871. Besides the château of Pontchartrain, Henckel gave her the famous yellow Donnersmarck Diamonds - one pear-shaped and weighing , the other cushion-shaped and . Horace de Viel-Castel

Marc-Roch-Horace de Salviac, comte de Viel-Castel, known as Horace de Viel-Castel (16 August 1802 Paris – 1 October 1864), was an art lover and collector, and director of the Louvre until 1863. A Bonapartist, he staunchly supported Napoleon III. ...

wrote that she regularly wore some two million francs' worth of diamonds, pearls and other gems.

It was widely believed, but never proved, that La Païva and her husband were asked to leave France in 1877 on suspicion of espionage. In any case, Henckel brought his wife to live in his castle at Neudeck in Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

. He had a second estate at Hochdorf in Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

.

His second wife was Russian noblewoman Katharina Slepzow (b. St. Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, 16 February 1862 – d. Koslowagora, 10 February 1929), former wife of Nikolay Muraviev

Nikolay Valerianovich Muraviev or Muravyov (russian: Никола́й Валериа́нович Муравьёв) (1850–1908) (anglicized Nicholas V. Muravev) was an Imperial Russian politician, nephew of the famed Count Nikolay Muravyov-Am ...

. They were married at Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

on 11 May 1887. They had two children, Guido Otto Karl Lazarus (1888–1959) and Kraft Raul Paul Alfred Ludwig Guido (1890–1977)

The prince commissioned a superb tiara for Princess Katharina, composed of 11 exceptionally rare Colombian emerald pear-shaped drops, which weigh over 500 carats and which are believed to have been in the Empress Eugénie's personal collection. The most valuable emerald and diamond tiara to have appeared at auction in the past 30 years, was auctioned by Sotheby's for CHF 11,282,500, CHF 2 million more than the highest estimate, on May 17, 2011 in Geneva. The Donnersmarcks' jewellery collection was known to be on a par with, or even to have exceeded, those of many of the crowned heads of Europe.

Later life

Henckel remained interested in political affairs even in the last years of his long life. Beginning in the winter of 1913-14 he had numerous conversations with US AmbassadorJames W. Gerard

James Watson Gerard III (August 25, 1867 – September 6, 1951) was a United States lawyer, diplomat, and justice of the New York Supreme Court.

Early life

Gerard was born in Geneseo, New York. His father, James Watson Gerard Jr., was a law ...

, to whom he described his role in the French indemnity negotiations of 1871. He expressed his long-standing support for a protective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

on agricultural products as well as government encouragement of German manufacturing interests. Henckel proposed that Gerard should take his second son, then nearly 24, to America to see the great iron and coal districts of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

.

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Henckel advocated levying a war indemnity even larger than that of 1871. In 1915 he joined Fürst Hermann von Hatzfeldt

Prince Hermann von Hatzfeldt, Duke of Trachenburg (4 February 1848, Trachenberg – 14 January 1933) was a German nobleman, member of the House of Hatzfeld, civil servant and politician. He represented the Deutsche Reichspartei in the Reichsta ...

(head of the German Red Cross

The German Red Cross (german: Deutsches Rotes Kreuz ; DRK) is the national Red Cross Society in Germany.

With 4 million members, it is the third largest Red Cross society in the world. The German Red Cross offers a wide range of services withi ...

), Bernhard Dernburg

Bernhard Dernburg (17 July 1865 – 14 October 1937) was a German liberal politician and banker. He served as the secretary for Colonial Affairs and head of the Imperial Colonial Office from May 1907 to 9 June 1910, and as the minister of Finance ...

, Hans Delbrück

Hans Gottlieb Leopold Delbrück (; 11 November 1848 – 14 July 1929) was a German historian. Delbrück was one of the first modern military historians, basing his method of research on the critical examination of ancient sources, using auxiliary ...

, Adolf von Harnack

Carl Gustav Adolf von Harnack (born Harnack; 7 May 1851 – 10 June 1930) was a Baltic German Lutheran theologian and prominent Church historian. He produced many religious publications from 1873 to 1912 (in which he is sometimes credited ...

and others in signing a petition opposing the annexation of Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

.

Seeing through the military's glib propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loa ...

and increasingly anxious about Germany's growing war debt, Henckel von Donnersmarck died in Berlin in December 1916 at the age of 86.

Legacy

Following World War I, Neudeck passed to Polish sovereignty asŚwierklaniec

Świerklaniec (; german: Neudeck) is a village in Tarnowskie Góry County, in the Silesian Voivodeship of southwestern Poland. Formerly, from 1975—1998, Świerklaniec was a part of the Katowice Voivodeship.

Geography

Świerklaniec lies appro ...

; Hochdorf remained in German territory until 1945. Katharina Fürstin Henckel von Donnersmarck died at Koslowagora, today Kozłowa Góra, neighbourhood of Piekary Śląskie

Piekary Śląskie () (german: Deutsch Piekar; szl, Piekary) is a city in Silesia in southern Poland, near Katowice. The north district of the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Union – metropolis with the population of 2 million. Located in the Silesia ...

, in February 1929.

A decade later, during the preparations for the German invasion of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

, Guido's son, Guido Otto Karl Lazarus Fürst Henckel von Donnersmarck met with ''Oberstleutnant'' Erwin Lahousen

Generalmajor Erwin Heinrich René Lahousen, Edler von Vivremont (25 October 1897 – 24 February 1955) was a high-ranking Abwehr official during the Second World War, as well as a member of the German Resistance and a key player in attempts to as ...

of ''Abwehr'' (military intelligence) at Hochdorf on 11 June 1939 to offer the assistance of the entire forestry staff of his Polish estate. The offer was accepted. With the German defeat in 1945 and the coming of Communist rule, the family's estates were confiscated, and they went into exile in the West.

The confiscated Neudeck estates were turned into a park, and the buildings were razed in 1962, but underground tunnels still exist.

Honours

*Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) constituted the German state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: ...

:Handbuch über den Königlich Preußischen Hof und Staat

' (1908), Herrenhaus p. 218 ** Knight of the

Wilhelm-Orden

The Imperial and Royal Order of Wilhelm ('' in English'' "William-Order") was instituted on 18 January 1896 by the German Emperor and King of Prussia Willhelm II as a high civilian award, and was dedicated to the memory of his grandfather Emper ...

** Grand Cross of the Red Eagle

** Knight of the Prussian Crown, 1st Class

** Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia e ...

(1870), 2nd Class on White Band with Black Edge

** Knight of Justice of the Johanniter Order

* Ernestine duchies

The Ernestine duchies (), also known as the Saxon duchies (, although the Albertine appanage duchies of Weissenfels, Merseburg and Zeitz were also "Saxon duchies" and adjacent to several Ernestine ones), were a group of small states whose n ...

: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order

The Saxe-Ernestine House Order (german: link=yes, Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden)Hausorden

Herz ...

Herz ...

See also

*Henckel von Donnersmarck

The House of Henckel von Donnersmarck is an old Austro-German noble family that originated in the former region of Spiš in Upper Hungary, now in Slovakia. The founder of the family was Henckel de Quintoforo in the 14/15th century. The original ...

family line

References

Notes

* *External links

Fürst Donnersmarck-Stiftung zu Berlin - Foundation for people with disabilities founded 1916 by Fürst von Donnersmarck

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henckel Von Donnersmarck, Guido 1830 births 1916 deaths German company founders German industrialists German landowners German mining businesspeople Members of the Prussian House of Lords

Guido

Guido is a given name Latinised from the Old High German name Wido. It originated in Medieval Italy. Guido later became a male first name in Austria, Germany, the Low Countries, Scandinavia, Spain, Portugal, Latin America and Switzerland. The m ...

People from the Province of Silesia

Nobility from Wrocław

Businesspeople from Paris

Recipients of the Iron Cross (1870), 2nd class