Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in

Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

. It is bordered to the north and west by

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

; to the northeast by

Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wate ...

and the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

; to the east by

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

; to the southeast by

El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

and to the south by the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

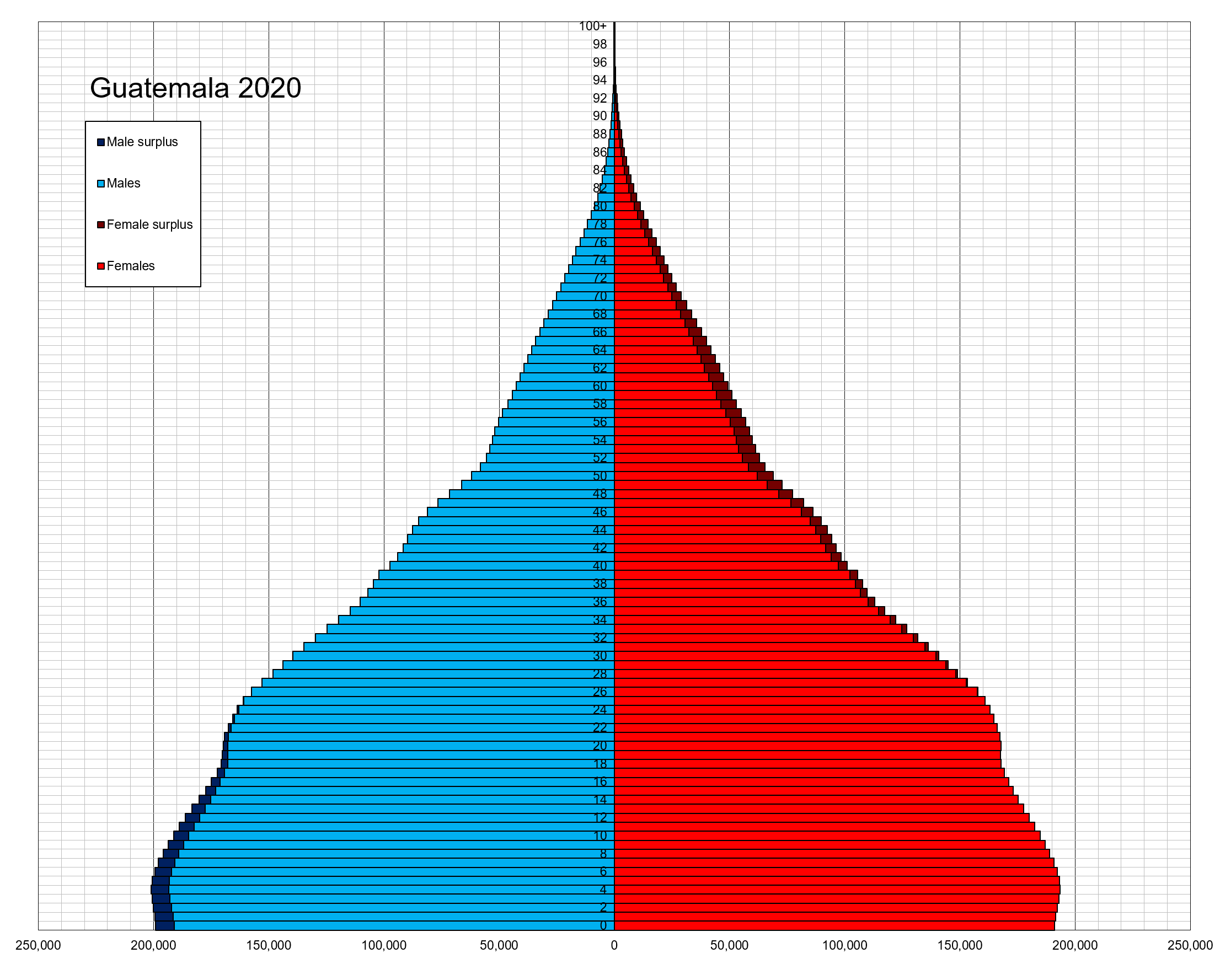

. With an estimated population of around million, Guatemala is the most populous country in Central America and the 11th most populous country in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

. It is a

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represen ...

with its capital and largest city being Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, also known as

Guatemala City

Guatemala City ( es, Ciudad de Guatemala), known locally as Guatemala or Guate, is the capital and largest city of Guatemala, and the most populous urban area in Central America. The city is located in the south-central part of the country, nest ...

, the most populous city in Central America.

The territory of modern Guatemala hosted the core of the

Maya civilization

The Maya civilization () of the Mesoamerican people is known by its ancient temples and glyphs. Its Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. It is also noted for its art, archit ...

, which extended across

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

. In the 16th century, most of this area was

conquered by the Spanish and claimed as part of the

viceroyalty

A viceroyalty was an entity headed by a viceroy. It dates back to the Spanish conquest of the Americas in the sixteenth century.

France

*Viceroyalty of New France

Portuguese Empire

In the scope of the Portuguese Empire, the term "Viceroyalty o ...

of

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

. Guatemala attained independence in 1821 from Spain and Mexico. In 1823, it became part of the

Federal Republic of Central America

The Federal Republic of Central America ( es, República Federal de Centroamérica), originally named the United Provinces of Central America ( es, Provincias Unidas del Centro de América), and sometimes simply called Central America, in it ...

, which dissolved by 1841.

From the mid- to late 19th century, Guatemala suffered chronic instability and civil strife. Beginning in the early 20th century, it was ruled by a series of dictators backed by the

United Fruit Company

The United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) was an American multinational corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. The company was formed in 1899 fro ...

and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

. In 1944, authoritarian leader

Jorge Ubico

Jorge Ubico Castañeda (10 November 1878 – 14 June 1946), nicknamed Number Five or also Central America's Napoleon, was a Guatemalan dictator. A general in the Guatemalan army, he was elected to the presidency in 1931, in an election where ...

was overthrown by a pro-democratic military coup, initiating a

decade-long revolution that led to sweeping social and economic reforms. A

U.S.-backed military coup in 1954 ended the revolution and installed a dictatorship.

From 1960 to 1996, Guatemala

endured a bloody civil war fought between the U.S.-backed government and

leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

rebels, including

genocidal massacres

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lati ...

of the Maya population perpetrated by the military. A peace accord negotiated by the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

has resulted in continued economic growth and successful democratic elections, although poverty, crime, drug trafficking, and civil instability remain major issues.

, Guatemala ranks 31st of 33 Latin American and Caribbean countries in the

Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, whi ...

. Although rich in export goods, around a quarter of the population (4.6 million) face

food insecurity

Food security speaks to the availability of food in a country (or geography) and the ability of individuals within that country (geography) to access, afford, and source adequate foodstuffs. According to the United Nations' Committee on World F ...

, which has been worsened by the ongoing food crisis resulting from the

Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014. The invasion has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths on both sides. It has caused Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II. An ...

.

Guatemala's abundance of biologically significant and unique ecosystems includes many endemic species and contributes to Mesoamerica's designation as a

biodiversity hotspot

A biodiversity hotspot is a biogeographic region with significant levels of biodiversity that is threatened by human habitation. Norman Myers wrote about the concept in two articles in ''The Environmentalist'' in 1988 and 1990, after which the co ...

.

Etymology

The name "Guatemala" comes from the

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller ...

word ''Cuauhtēmallān'', or "place of many trees", a derivative of the

K'iche' Mayan word for "many trees" or, perhaps more specifically, for the Cuate/Cuatli tree

Eysenhardtia

''Eysenhardtia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the family Fabaceae. It belongs to the subfamily Faboideae. Members of the genus are commonly known as kidneywoods.

Species

''Eysenhardtia'' comprises the following species:

* '' Eysenhardtia ad ...

. This was the name that the

Tlaxcaltecan warriors who accompanied

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucatá ...

during the

Spanish Conquest

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its predece ...

gave to this territory.

History

Pre-Columbian

The first evidence of human habitation in Guatemala dates to 12,000 BC. Archaeological evidence, such as

obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements s ...

arrowhead

An arrowhead or point is the usually sharpened and hardened tip of an arrow, which contributes a majority of the projectile mass and is responsible for impacting and penetrating a target, as well as to fulfill some special purposes such as sign ...

s found in various parts of the country, suggests a human presence as early as 18,000 BC. There is archaeological proof that early Guatemalan settlers were

hunter-gatherers

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

. Pollen samples from

Petén and the Pacific coast indicate that

maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

cultivation had been developed by the people by 3500 BC. Sites dating to 6500 BC have been found in the

Quiché region in the Highlands, and

Sipacate

Sipacate is a resort town and municipality on the Pacific coast of Guatemala, in Escuintla Department about west of Puerto San José. It is promoted as a venue for surfing. Being roughly in the center of the Guatemalan coastline, it is used as a ...

and

Escuintla

Escuintla () is an industrial city in Guatemala, its land extension is 4384 km², and it is nationally known for its sugar agribusiness. Its capital is a minicipality with the same name. Citizens celebrate from December 6 to 9 with a small fair i ...

on the central Pacific coast.

Archaeologists divide the

pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, th ...

history of Mesoamerica into the Preclassic period (3000 BC to 250 AD), the Classic period (250 to 900 AD), and the Postclassic period (900 to 1500 AD). Until recently, the Preclassic was regarded by researchers as a formative period, in which the peoples typically lived in huts in small villages of farmers, with few permanent buildings. This notion has been challenged since the late 20th century by discoveries of monumental architecture from that period, such as an altar in

La Blanca

La Blanca is a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in present-day La Blanca, San Marcos Department, western Guatemala. It has an occupation dating predominantly from the Middle Preclassic (900–600 BC) period of Mesoamerican chro ...

,

San Marcos

San Marcos is the Spanish name of Saint Mark. It may also refer to:

Towns and cities Argentina

* San Marcos, Salta

Colombia

* San Marcos, Antioquia

* San Marcos, Sucre

Costa Rica

* San Marcos, Costa Rica (aka San Marcos de Tarrazú)

...

, from 1000 BC; ceremonial sites at Miraflores and

Naranjo

Naranjo is a Pre-Columbian Maya city in the Petén Basin region of Guatemala. It was occupied from about 500 BC to 950 AD, with its height in the Late Classic Period. The site is part of Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo National Park. The city lies along the ...

from 801 BC; the earliest monumental masks; and the

Mirador Basin

The Mirador Basin is a hypothesized geological depression found in the remote rainforest of the northern department of Petén, Guatemala. Mirador Basin consists of two true basins, consisting of shallowly sloping terrain dominated by low-lying s ...

cities of

Nakbé

Nakbe is one of the largest early Maya archaeological sites. Nakbe is located in the Mirador Basin, in the Petén region of Guatemala, approximately 13 kilometers south of the largest Maya city of El Mirador. Excavations at Nakbe suggest that hab ...

, Xulnal,

El Tintal

El Tintal is a Maya archaeological site in the northern Petén region of Guatemala, about northeast of the modern-day settlement of Carmelita, with settlement dating to the Preclassic and Classic periods. It is close to the better known sit ...

, Wakná and

El Mirador

El Mirador (which translates as "the lookout", "the viewpoint", or "the belvedere") is a large pre-Columbian Middle and Late Preclassic (1000 BC - 250 AD) Mayan settlement, located in the north of the modern department of El Petén, Guatemal ...

.

On 3 June 2020, researchers published an article in ''

Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'' describing their discovery of the oldest and largest Maya site, known as

Aguada Fénix

Aguada Fénix is a large Preclassic Mayan ruin located in the state of Tabasco, Mexico, near the border with Guatemala. The site was discovered by aerial survey using laser mapping, and announced in 2020. The flattened mound, nearly a mile in l ...

, in

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

. It features monumental architecture, an elevated, rectangular plateau measuring about 1,400 meters long and nearly 400 meters wide, constructed of a mixture of earth and clay. To the west is a 10-meter-tall earthen mound. Remains of other structures and reservoirs were also detected through the

Lidar

Lidar (, also LIDAR, or LiDAR; sometimes LADAR) is a method for determining ranges (variable distance) by targeting an object or a surface with a laser and measuring the time for the reflected light to return to the receiver. It can also be ...

technology. It is estimated to have been built from 1000 to 800 BC, demonstrating that the Maya built large, monumental complexes from their early period.

The Classic period of

Mesoamerican

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Withi ...

civilization corresponds to the height of the

Maya civilization

The Maya civilization () of the Mesoamerican people is known by its ancient temples and glyphs. Its Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. It is also noted for its art, archit ...

. It is represented by countless sites throughout Guatemala, although the largest concentration is in

Petén. This period is characterized by urbanisation, the emergence of independent city-states, and contact with other Mesoamerican cultures.

This lasted until approximately 900 AD, when the

Classic Maya civilization collapsed.

The Maya abandoned many of the cities of the central lowlands or were killed by a drought-induced

famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

.

The cause of the collapse is debated, but the drought theory is gaining currency, supported by evidence such as lakebeds, ancient pollen, and others.

A series of prolonged droughts in what is otherwise a seasonal desert is thought to have decimated the Maya, who relied on regular rainfall to support their dense population.

The Post-Classic period is represented by regional kingdoms, such as the

Itza Itza may refer to:

* Itza people, an ethnic group of Guatemala

* Itzaʼ language, a Mayan language

* Itza Kingdom (disambiguation)

* Itza, Navarre, a town in Spain

See also

* Chichen Itza

Chichen Itza , es, Chichén Itzá , often with ...

,

Kowoj

The Kowoj oʔwox(also recorded as ''Ko'woh'', ''Couoh'', ''Coguo'', ''Cohuo'', ''Kob'ow'' and ''Kob'ox'', and ''Kowo'') was a Maya group and polity, from the Late Postclassic period (ca. 1250–1697) of Mesoamerican chronology. The Kowoj clai ...

,

Yalain

The Yalain have been proposed as a Maya polity that existed during the Postclassic period (c. AD 1000–1697) in the Petén Basin of northern Guatemala, based in the central Petén lakes region.Rice and Rice 2009, p. 11. A small town called Yalai ...

and

Kejache

The Kejache () (sometimes spelt Kehache, Quejache, Kehach, Kejach or Cehache) were a Maya people in northern Guatemala at the time of Spanish contact in the 17th century. The Kejache territory was located in the Petén Basin in a region that takes ...

in Petén, and the

Mam,

Ki'che',

Kackchiquel,

Chajoma

The Chajoma () were a Kaqchikel-speaking Maya people of the Late Postclassic period, with a large kingdom in the highlands of Guatemala. According to the indigenous chronicles of the K'iche' and the Kaqchikel, there were three principal Postclas ...

,

Tz'utujil,

Poqomchi',

Q'eqchi' and

Ch'orti' peoples in the highlands. Their cities preserved many aspects of Maya culture.

The Maya civilization shares many features with other Mesoamerican civilizations due to the high degree of interaction and

cultural diffusion

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technologi ...

that characterized the region. Advances such as writing,

epigraphy

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

, and the

calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is also a physi ...

did not originate with the Maya; however, their civilization fully developed them. Maya influence can be detected from

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

,

Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wate ...

, Guatemala, and Northern

El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

to as far north as central Mexico, more than from the

Maya area. Many outside influences are found in

Maya art

Ancient Maya art is the visual arts of the Maya civilization, an eastern and south-eastern Mesoamerican culture made up of a great number of small kingdoms in present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras. Many regional artistic traditions ex ...

and architecture, which are thought to have resulted from trade and cultural exchange rather than direct external conquest.

Archaeological investigation

In 2018, 60,000 uncharted structures were revealed in northern Guatemala by archaeologists with the help of

Lidar

Lidar (, also LIDAR, or LiDAR; sometimes LADAR) is a method for determining ranges (variable distance) by targeting an object or a surface with a laser and measuring the time for the reflected light to return to the receiver. It can also be ...

technology lasers. The project applied Lidar technology on an area of 2,100 square kilometers in the

Maya Biosphere Reserve

The Maya Biosphere Reserve ( es, Reserva de la Biosfera Maya) is a nature reserve in Guatemala managed by Guatemala's National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP). The Maya Biosphere Reserve covers an area of 21,602 km², one-fifth of the c ...

in the

Petén region of Guatemala. Thanks to the new findings, archaeologists believe that 7–11 million

Maya people

The Maya peoples () are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that historical reg ...

inhabited northern Guatemala during the late classical period from 650 to 800 A.D., twice the estimated population of medieval England.

Lidar technology digitally removed the tree canopy to reveal ancient remains and showed that Maya cities, such as

Tikal

Tikal () (''Tik’al'' in modern Mayan orthography) is the ruin of an ancient city, which was likely to have been called Yax Mutal, found in a rainforest in Guatemala. It is one of the largest archeological sites and urban centers of the pre-Co ...

, were larger than previously assumed. The use of Lidar revealed numerous houses, palaces, elevated highways, and defensive fortifications. According to archaeologist Stephen Houston, it is one of the most overwhelming findings in over 150 years of Maya archaeology.

Spanish era (1519–1821)

After they arrived in the

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

, the Spanish started several expeditions to Guatemala, beginning in 1519. Before long, Spanish contact resulted in an epidemic that devastated native populations.

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

, who had led the

Spanish conquest of Mexico

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, also known as the Conquest of Mexico or the Spanish-Aztec War (1519–21), was one of the primary events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. There are multiple 16th-century narratives of the eve ...

, granted a permit to Captains Gonzalo de Alvarado and his brother,

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucatá ...

, to conquer this land. Alvarado at first allied himself with the

Kaqchikel nation to fight against their traditional rivals the

K'iche' (Quiché) nation. Alvarado later turned against the Kaqchikel, and eventually brought the entire region under Spanish domination.

During the colonial period, Guatemala was an

audiencia, a

captaincy-general (''

Capitanía General de Guatemala'') of Spain, and a part of

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

(Mexico). The first capital, Villa de Santiago de Guatemala (now known as

Tecpan Guatemala), was founded on 25 July 1524 near

Iximché

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandon ...

, the Kaqchikel capital city. The capital was moved to

Ciudad Vieja

Ciudad Vieja () is a town and municipality in the Guatemalan department of Sacatepéquez. According to the 2018 census, the town has a population of 32,802 on 22 November 1527, as a result of a Kaqchikel attack on Villa de Santiago de Guatemala. Owing to its strategic location on the American Pacific Coast, Guatemala became a supplementary node to the Transpacific

Manila Galleon

fil, Galyon ng Maynila

, english_name = Manila Galleon

, duration = From 1565 to 1815 (250 years)

, venue = Between Manila and Acapulco

, location = New Spain (Spanish Empire) ...

trade connecting Latin America to Asia via the Spanish owned Philippines.

On 11 September 1541, the new capital was flooded when the lagoon in the

crater

Crater may refer to:

Landforms

*Impact crater, a depression caused by two celestial bodies impacting each other, such as a meteorite hitting a planet

*Explosion crater, a hole formed in the ground produced by an explosion near or below the surfac ...

of the

Agua Volcano collapsed due to heavy rains and earthquakes; the capital was then moved to

Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

in the Panchoy Valley, now a

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

. This city was destroyed by several earthquakes in 1773–1774. The King of Spain authorized moving the capital to its current location in the Ermita Valley, which is named after a

Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

dedicated to the

Virgen del Carmen

Our Lady of Mount Carmel, or Virgin of Carmel, is the title given to the Blessed Virgin Mary in her role as patroness of the Carmelite Order, particularly within the Catholic Church. The first Carmelites were Christian hermits living on Mount Car ...

. This new capital was founded on 2 January 1776.

Independence and the 19th century (1821–1847)

On 15 September 1821, the

Captaincy General of Guatemala

The Captaincy General of Guatemala ( es, Capitanía General de Guatemala), also known as the Kingdom of Guatemala ( es, Reino de Guatemala), was an administrative division of the Spanish Empire, under the viceroyalty of New Spain in Central A ...

, an administrative region of the Spanish Empire consisting of

Chiapas

Chiapas (; Tzotzil language, Tzotzil and Tzeltal language, Tzeltal: ''Chyapas'' ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Chiapas), is one of the states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, ...

, Guatemala,

El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Honduras, officially proclaimed its independence from Spain at a public meeting in Guatemala City. Independence from Spain was gained, and the Captaincy General of Guatemala

joined the

First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era, ...

under

Agustín de Iturbide

Agustín de Iturbide (; 27 September 178319 July 1824), full name Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu and also known as Agustín of Mexico, was a Mexican army general and politician. During the Mexican War of Independence, he built a ...

.

Under the First Empire, Mexico reached its greatest territorial extent, stretching from northern California to the provinces of Central America (excluding Panama, which was then part of Colombia), which had not initially approved becoming part of the Mexican Empire but joined the Empire shortly after their independence. This region was formally a part of the

Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

throughout the colonial period, but as a practical matter had been administered separately. It was not until 1825 that Guatemala created its own flag.

In 1838 the liberal forces of Honduran leader

Francisco Morazán

José Francisco Morazán Quesada (; born October 3, 1792 – September 15, 1842) was a Central American politician who served as president of the Federal Republic of Central America from 1830 to 1839. Before he was president of Central America h ...

and Guatemalan

José Francisco Barrundia

José Francisco Barrundia y Cepeda (May 12, 1787, Guatemala City – August 4, 1854, New York City) was a liberal Central American politician. From June 26, 1829 to September 16, 1830 he was interim president of the United Provinces of Centr ...

invaded Guatemala and reached San Sur, where they executed Chúa Alvarez, father-in-law of

Rafael Carrera

José Rafael Carrera y Turcios (24 October 1814 – 14 April 1865) was the president of Guatemala from 1844 to 1848 and from 1851 until his death in 1865, after being appointed President for life in 1854. During his military career and presiden ...

, then a military commander and later the first president of Guatemala. The liberal forces impaled Alvarez's head on a pike as a warning to followers of the Guatemalan

caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; osp, cabdillo, from Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise definition of ''caudillo'', which is often used interchangeably with " ...

. Carrera and his wife Petrona – who had come to confront Morazán as soon as they learned of the invasion and were in

Mataquescuintla

Mataquescuintla (from Nahuatl, meaning ''net to catch dogs'') is a town and municipality in the Jalapa department of south-east Guatemala. It covers .

Mataquescuintla played a significant role during the first half of the nineteenth century, when ...

– swore they would never forgive Morazán even in his grave; they felt it impossible to respect anyone who would not avenge family members.

After sending several envoys, whom Carrera would not receive – and especially not Barrundia whom Carrera did not want to murder in cold blood – Morazán began a scorched-earth offensive, destroying villages in his path and stripping them of assets. The Carrera forces had to hide in the mountains. Believing Carrera totally defeated, Morazán and Barrundia marched to

Guatemala City

Guatemala City ( es, Ciudad de Guatemala), known locally as Guatemala or Guate, is the capital and largest city of Guatemala, and the most populous urban area in Central America. The city is located in the south-central part of the country, nest ...

, and were welcomed as saviors by state governor Pedro Valenzuela and members of the conservative , who proposed to sponsor one of the liberal battalions, while Valenzuela and Barrundia gave Morazán all the Guatemalan resources needed to solve any financial problem he had. The

criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. In different Latin American countries the word has come to have different meanings, sometimes referring to the local-born majo ...

of both parties celebrated until dawn that they finally had a criollo caudillo like Morazán, who was able to crush the peasant rebellion.

Morazán used the proceeds to support Los Altos and then replaced Valenzuela with

Mariano Rivera Paz

Mariano Rivera Paz (24 December 1804 – 26 February 1849) was Head of State of Guatemala and its first president.

Biography

Mariano Rivera Paz was born in Guatemala City and studied law in the Royal and Pontifical University of San Carlo ...

, a member of the Aycinena clan, although he did not return to that clan any property confiscated in 1829. In revenge,

Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol

Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol (Guatemala City, 29 August 1792 – Guatemala City, 17 February 1865) was an ecclesiastical and intellectual conservative in Central America. He was President of the Pontifical University of San Carlos Borrome ...

voted to dissolve the

Central American Federation

The Federal Republic of Central America ( es, República Federal de Centroamérica), originally named the United Provinces of Central America ( es, Provincias Unidas del Centro de América), and sometimes simply called Central America, in it ...

in

San Salvador

San Salvador (; ) is the capital and the largest city of El Salvador and its eponymous department. It is the country's political, cultural, educational and financial center. The Metropolitan Area of San Salvador, which comprises the capital i ...

a little later, forcing Morazán to return to El Salvador to fight for his federal mandate. Along the way, Morazán increased repression in eastern Guatemala, as punishment for helping Carrera. Knowing that Morazán had gone to El Salvador, Carrera tried to take

Salamá

Salamá is a city in Guatemala. It is the capital of the department of Baja Verapaz and it is situated at 940 m above sea level. The municipality of Salamá, for which the city of Salamá serves as the administrative centre, covers a total s ...

with the small force that remained, but was defeated, and lost his brother Laureano in combat. With just a few men left, he managed to escape, badly wounded, to

. After recovering somewhat, he attacked a detachment in

Jutiapa

Jutiapa is a city and a municipality in the Jutiapa department of Guatemala.

Located 124 km from the city of Guatemala City, at an altitude of 892 m (2,926 ft), and got a small amount of booty which he gave to the volunteers who accompanied him. He then prepared to attack

Petapa

San Miguel Petapa () also known as Petapa is a city and municipality in the Guatemala department of Guatemala, located south of Guatemala City. The city has a population of 129,124 according to the 2018 census.Carlos Salazar Castro

Carlos Salazar Castro (1800 in San Salvador, El Salvador – July 23, 1867 in San José, Costa Rica) was a Central American military officer and Liberal politician. Briefly in 1834 he was provisional president of El Salvador, and in 1839 h ...

defeated him in the fields of

Villa Nueva and Carrera had to retreat. After unsuccessfully trying to take

Quetzaltenango

Quetzaltenango (, also known by its Maya name Xelajú or Xela ) is both the seat of the namesake Department and municipality, in Guatemala.

The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of above sea level at its lowest part. It may ...

, Carrera found himself both surrounded and wounded. He had to capitulate to Mexican General

Agustin Guzman, who had been in Quetzaltenango since

Vicente Filísola

Vicente Filísola (born Vincenzo Filizzola; 1785 – 23 July 1850) was an Italian-born Spanish and Mexican military and political figure during the 19th century. He is most well known for his role in leading the short-lived Mexican annexation ...

's arrival in 1823. Morazán had the opportunity to shoot Carrera, but did not, because he needed the support of the Guatemalan peasants to counter the attacks of

Francisco Ferrera

Francisco Ferrera (29 January 1794 – 10 April 1851) was a president of Honduras. He was born in San Juan de Flores, Honduras.

Ferrera joined the guerrerista campaigns of General Francisco Morazán

José Francisco Morazán Quesada (; b ...

in

El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

. Instead, Morazán left Carrera in charge of a small fort in Mita, without any weapons. Knowing that Morazán was going to attack El Salvador,

Francisco Ferrera

Francisco Ferrera (29 January 1794 – 10 April 1851) was a president of Honduras. He was born in San Juan de Flores, Honduras.

Ferrera joined the guerrerista campaigns of General Francisco Morazán

José Francisco Morazán Quesada (; b ...

gave arms and ammunition to Carrera and convinced him to attack Guatemala City.

Meanwhile, despite insistent advice to definitively crush Carrera and his forces, Salazar tried to negotiate with him diplomatically; he even went as far as to show that he neither feared nor distrusted Carrera by removing the fortifications of the Guatemalan capital, in place since the battle of Villa Nueva. Taking advantage of Salazar's good faith and Ferrera's weapons, Carrera took Guatemala City by surprise on 13 April 1839; Salazar,

Mariano Gálvez

José Felipe Mariano Gálvez (ca. 1794 – March 29, 1862 in Mexico) was a jurist and Liberal politician in Guatemala. For two consecutive terms from August 28, 1831, to March 3, 1838, he was chief of state of the State of Guatemala, within th ...

and Barrundia fled before the arrival of Carrera's militiamen. Salazar, in his nightshirt, vaulted roofs of neighboring houses and sought refuge, reaching the border disguised as a peasant. With Salazar gone, Carrera reinstated Rivera Paz as head of state.

Between 1838 and 1840 a

secessionist movement

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

in the city of

Quetzaltenango

Quetzaltenango (, also known by its Maya name Xelajú or Xela ) is both the seat of the namesake Department and municipality, in Guatemala.

The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of above sea level at its lowest part. It may ...

founded the breakaway state of

Los Altos and sought independence from Guatemala. The most important members of the Liberal Party of Guatemala and liberal enemies of the conservative régime moved to Los Altos, leaving their exile in El Salvador. The liberals in Los Altos began severely criticizing the Conservative government of Rivera Paz. Los Altos was the region with the main production and economic activity of the former state of Guatemala. Without Los Altos, conservatives lost many of the resources that had given Guatemala hegemony in Central America. The government of Guatemala tried to reach a peaceful solution, but two years of bloody conflict followed.

On 17 April 1839, Guatemala declared itself independent from the United Provinces of Central America. In 1840, Belgium began to act as an external source of support for Carrera's independence movement, in an effort to exert influence in Central America. The ''Compagnie belge de colonisation'' (Belgian Colonization Company), commissioned by Belgian

King Leopold I

* nl, Leopold Joris Christiaan Frederik

* en, Leopold George Christian Frederick

, image = NICAISE Leopold ANV.jpg

, caption = Portrait by Nicaise de Keyser, 1856

, reign = 21 July 1831 –

, predecessor = Erasme Loui ...

, became the administrator of

Santo Tomas de Castilla replacing the failed British

Eastern Coast of Central America Commercial and Agricultural Company. Even though the colony eventually crumbled, Belgium continued to support Carrera in the mid-19th century, although Britain continued to be the main business and political partner to Carrera. Rafael Carrera was elected Guatemalan Governor in 1844.

Settlers from Germany arrived in the mid-19th century. German settlers acquired land and grew coffee plantations in Alta Verapaz and Quetzaltenango.

Republic (1847–1851)

On 21 March 1847, Guatemala declared itself an independent republic and Carrera became its first president.

During the first term as president, Carrera brought the country back from extreme conservatism to a traditional moderation; in 1848, the liberals were able to drive him from office, after the country had been in turmoil for several months. Carrera resigned of his own free will and left for México. The new liberal regime allied itself with the Aycinena family and swiftly passed a law ordering Carrera's execution if he returned to Guatemalan soil.

The liberal criollos from

Quetzaltenango

Quetzaltenango (, also known by its Maya name Xelajú or Xela ) is both the seat of the namesake Department and municipality, in Guatemala.

The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of above sea level at its lowest part. It may ...

were led by general

Agustín Guzmán

Agustín Guzmán, nicknamed "The Altense Hero", was a liberal Central American military general, politician and positivist, who was appointed as Army Commander in Chief of the State of Los Altos when it was formed as part of the Federal Republ ...

who occupied the city after Corregidor general

Mariano Paredes was called to

Guatemala City

Guatemala City ( es, Ciudad de Guatemala), known locally as Guatemala or Guate, is the capital and largest city of Guatemala, and the most populous urban area in Central America. The city is located in the south-central part of the country, nest ...

to take over the presidential office. They declared on 26 August 1848 that Los Altos was an independent state once again. The new state had the support of

Doroteo Vasconcelos

Doroteo Vasconcelos Vides y Ladrón de Guevara (February 6, 1803–March 10, 1883) was President of El Salvador 7 February 1848 - 1 February 1850 and 4 February 1850 – 1 March 1851. Vasconcelos was close friend of Honduran general Francisco ...

' régime in

El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

and the rebel guerrilla army of Vicente and Serapio Cruz, who were sworn enemies of Carrera. The interim government was led by Guzmán himself and had Florencio Molina and the priest Fernando Davila as his Cabinet members. On 5 September 1848, the criollos altenses chose a formal government led by Fernando Antonio Martínez.

In the meantime, Carrera decided to return to Guatemala and did so, entering at

Huehuetenango

Huehuetenango () is a city and municipality in the highlands of western Guatemala. It is also the capital of the department of Huehuetenango. The city is situated from Guatemala City, and is the last departmental capital on the Pan-American Highw ...

, where he met with native leaders and told them that they must remain united to prevail; the leaders agreed and slowly the segregated native communities started developing a new Indian identity under Carrera's leadership. In the meantime, in the eastern part of Guatemala, the

Jalapa

Xalapa or Jalapa (, ), officially Xalapa-Enríquez (), is the capital city of the Mexican state of Veracruz and the name of the surrounding municipality. In the 2005 census the city reported a population of 387,879 and the municipality of which ...

region became increasingly dangerous; former president

Mariano Rivera Paz

Mariano Rivera Paz (24 December 1804 – 26 February 1849) was Head of State of Guatemala and its first president.

Biography

Mariano Rivera Paz was born in Guatemala City and studied law in the Royal and Pontifical University of San Carlo ...

and rebel leader Vicente Cruz were both murdered there after trying to take over the Corregidor office in 1849.

When Carrera arrived to

Chiantla

Chiantla () is a town and municipality in the Guatemalan department of Huehuetenango. The municipality is situated at 2,000 metres above sea level and covers an area of 521 km2. The annual festival is on January 28.

History Mercedaria ...

in

Huehuetenango

Huehuetenango () is a city and municipality in the highlands of western Guatemala. It is also the capital of the department of Huehuetenango. The city is situated from Guatemala City, and is the last departmental capital on the Pan-American Highw ...

, he received two altenses emissaries who told him that their soldiers were not going to fight his forces because that would lead to a native revolt, much like that of 1840; their only request from Carrera was to keep the natives under control. The altenses did not comply, and led by Guzmán and his forces, they started chasing Carrera; the caudillo hid, helped by his native allies and remained under their protection when the forces of

Miguel Garcia Granados

-->

Miguel is a given name and surname, the Portuguese and Spanish form of the Hebrew name Michael. It may refer to:

Places

* Pedro Miguel, a parish in the municipality of Horta and the island of Faial in the Azores Islands

* São Miguel (disam ...

arrived from

Guatemala City

Guatemala City ( es, Ciudad de Guatemala), known locally as Guatemala or Guate, is the capital and largest city of Guatemala, and the most populous urban area in Central America. The city is located in the south-central part of the country, nest ...

looking for him.

On learning that officer

José Víctor Zavala

José Víctor Ramón Valentín de las Ánimas Zavala y Córdova (November 2, 1815 – March 26, 1886) was a Guatemalan Field Marshal who participated in the wars of Rafael Carrera and the National War of Nicaragua against the invasion of Willia ...

had been appointed as Corregidor in Suchitepéquez, Carrera and his hundred

jacalteco

The Jakaltek (''Jacaltec'') language , also known as Jakalteko (''Jacalteco'') or Poptiʼ, is a Mayan languages, Mayan language of Guatemala spoken by 90,000 Jakaltek people in the department of Huehuetenango, and some 500 the adjoining part of ...

bodyguards crossed a dangerous jungle infested with

jaguar

The jaguar (''Panthera onca'') is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus '' Panthera'' native to the Americas. With a body length of up to and a weight of up to , it is the largest cat species in the Americas and the th ...

s to meet his former friend. Zavala not only did not capture him, he agreed to serve under his orders, thus sending a strong message to both liberal and conservatives in Guatemala City that they would have to negotiate with Carrera or battle on two fronts – Quetzaltenango and Jalapa. Carrera went back to the Quetzaltenango area, while Zavala remained in Suchitepéquez as a tactical maneuver. Carrera received a visit from a cabinet member of Paredes and told him that he had control of the native population and that he assured Paredes that he would keep them appeased. When the emissary returned to Guatemala City, he told the president everything Carrera said, and added that the native forces were formidable.

Guzmán went to

Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

to meet with another group of Paredes emissaries; they agreed that Los Altos would rejoin Guatemala, and that the latter would help Guzmán defeat his enemy and also build a port on the Pacific Ocean. Guzmán was sure of victory this time, but his plan evaporated when in his absence Carrera and his native allies occupied Quetzaltenango; Carrera appointed Ignacio Yrigoyen as

Corregidor

Corregidor ( tl, Pulo ng Corregidor, ) is an island located at the entrance of Manila Bay in the southwestern part of Luzon in the Philippines, and is considered part of the Province of Cavite. Due to this location, Corregidor has historically b ...

and convinced him that he should work with the K'iche', Q'anjobal and

Mam leaders to keep the region under control. On his way out, Yrigoyen murmured to a friend: "Now he is the king of the Indians, indeed!"

Guzmán then left for Jalapa, where he struck a deal with the rebels, while

Luis Batres Juarros

Luis Batres Juarros or Luis Batres y Juarros ( New Guatemala de la Asunción 7 May 1802 – 17 June 1862) was an influential conservative Guatemalan politician during the regime of General Rafael Carrera. Member of the Aycinena clan, was in c ...

convinced President Paredes to deal with Carrera. Back in Guatemala City within a few months, Carrera was commander-in-chief, backed by military and political support of the Indian communities from the densely populated western highlands. During the first presidency, from 1844 to 1848, he brought the country back from excessive conservatism to a moderate regime, and – with the advice of Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol and

Pedro de Aycinena

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for ''Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

– restored relations with the Church in Rome with a

Concordat

A concordat is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 st Ed ...

ratified in 1854.

Second Carrera government (1851–1865)

After Carrera returned from exile in 1849 the president of El Salvador,

Doroteo Vasconcelos

Doroteo Vasconcelos Vides y Ladrón de Guevara (February 6, 1803–March 10, 1883) was President of El Salvador 7 February 1848 - 1 February 1850 and 4 February 1850 – 1 March 1851. Vasconcelos was close friend of Honduran general Francisco ...

, granted asylum to the Guatemalan liberals, who harassed the Guatemalan government in several different ways. José Francisco Barrundia established a liberal newspaper for that specific purpose. Vasconcelos supported a rebel faction named "La Montaña" in eastern Guatemala, providing and distributing money and weapons. By late 1850, Vasconcelos was getting impatient at the slow progress of the war with Guatemala and decided to plan an open attack. Under that circumstance, the Salvadorean head of state started a campaign against the conservative Guatemalan regime, inviting

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

and

Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

to participate in the alliance; only the

Honduran government led by

Juan Lindo

Juan Nepomuceno Fernández Lindo y Zelaya (generally known as Juan Lindo) (16 May 1790, Tegucigalpa, Honduras – 23 April 1857, Gracias, Honduras) was a Conservative Central American politician, provisional president of the Republic of El S ...

accepted. In 1851 Guatemala defeated an Allied army from Honduras and El Salvador at the

Battle of La Arada

The Battle of La Arada () was fought on 2 February 1851 near the town of Chiquimula in Guatemala, between the forces of Guatemala and an Allied army from Honduras and El Salvador. As the most serious threat to Guatemala's liberty and sovereig ...

.

In 1854 Carrera was declared "supreme and perpetual leader of the nation" for life, with the power to choose his successor. He held that position until he died on 14 April 1865. While he pursued some measures to set up a foundation for economic prosperity to please the conservative landowners, military challenges at home and a three-year war with Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua dominated his presidency.

His rivalry with Gerardo Barrios, President of El Salvador, resulted in open war in 1863. At

Coatepeque the Guatemalans suffered a

severe defeat, which was followed by a truce. Honduras joined with El Salvador, and Nicaragua and Costa Rica with Guatemala. The contest was finally settled in favor of Carrera, who besieged and occupied

San Salvador

San Salvador (; ) is the capital and the largest city of El Salvador and its eponymous department. It is the country's political, cultural, educational and financial center. The Metropolitan Area of San Salvador, which comprises the capital i ...

, and dominated Honduras and Nicaragua. He continued to act in concert with the Clerical Party, and tried to maintain friendly relations with European governments. Before he died, Carrera nominated his friend and loyal soldier, Army Marshall

Vicente Cerna y Cerna

Vicente Cerna y Cerna (22 January 1815 – 27 June 1885) was president of Guatemala from 24 May 1865 to 29 June 1871. Loyal friend and comrade of Rafael Carrera, was appointed army's Field Marshal after Carraera's victory against Salvadorian lead ...

, as his successor.

Vicente Cerna y Cerna regime (1865–1871)

Vicente Cerna y Cerna

Vicente Cerna y Cerna (22 January 1815 – 27 June 1885) was president of Guatemala from 24 May 1865 to 29 June 1871. Loyal friend and comrade of Rafael Carrera, was appointed army's Field Marshal after Carraera's victory against Salvadorian lead ...

was

president of Guatemala

The president of Guatemala ( es, Presidente de Guatemala), officially known as the President of the Republic of Guatemala ( es, Presidente de la República de Guatemala), is the head of state and head of government of Guatemala, elected to a ...

from 24 May 1865 to 29 June 1871. Liberal author , described Marshall Cerna's government in the following manner:

The State and Church were a single unit, and the conservative régime was strongly allied to the power of

regular clergy

Regular clergy, or just regulars, are clerics in the Catholic Church who follow a rule () of life, and are therefore also members of religious institutes. Secular clergy are clerics who are not bound by a rule of life.

Terminology and history

The ...

of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, who were then among the largest landowners in Guatemala. The tight relationship between church and state had been ratified by the

Concordat of 1852, which was the law until Cerna was deposed in 1871. Even liberal generals like realized that Rafael Carrera's political and military presence made him practically invincible. Thus the generals fought under his command, and waited—for a long time—until Carrera's death before beginning their revolt against the tamer Cerna. During Cerna's presidency, liberal party members were prosecuted and sent into exile; among them, those who started the Liberal Revolution of 1871.

In 1871, the merchants guild, Consulado de Comercio, lost their exclusive court privilege. They had major effects on the economics of the time, and therefore land management. From 1839 to 1871, the Consulado held a consistent monopolistic position in the regime.

Liberal governments (1871–1898)

Guatemala's "Liberal Revolution" came in 1871 under the leadership of

Justo Rufino Barrios

Justo Rufino Barrios Auyón (19 July 1835 – 2 April 1885) was a Guatemalan politician and military general who served as President of Guatemala from 1873 to his death in 1885. He was known for his liberal reforms and his attempts to reuni ...

, who worked to modernize the country, improve trade, and introduce new crops and manufacturing. During this era coffee became an important crop for Guatemala. Barrios had ambitions of reuniting Central America and took the country to war in an unsuccessful attempt to attain it, losing his life on the battlefield in 1885 against forces in El Salvador.

Manuel Barillas

Manuel Lisandro Barillas Bercián (17 January 1845 – 7 April 1907) was a Guatemalan general and acting president of Guatemala from 6 April 1885 to 15 March 1886 and President from 16 March 1886 to 15 March 1892. He was born in Quetzaltenango, ...

was president from 16 March 1886 to 15 March 1892. Manuel Barillas was unique among liberal presidents of Guatemala between 1871 and 1944: he handed over power to his successor peacefully. When election time approached, he sent for the three Liberal candidates to ask them what their government plan would be. Happy with what he heard from general

Reyna Barrios, Barillas made sure that a huge column of Quetzaltenango and Totonicapán indigenous people came down from the mountains to vote for him. Reyna was elected president.

José María Reina Barrios

José María Reyna Barrios (24 December 1854 – 8 February 1898) was President of Guatemala from 15 March 1892 until his death on 8 February 1898. He was born in San Marcos, Guatemala and was nicknamed ''Reynita'', the diminutive form, bec ...

was president between 1892 and 1898. During Barrios's first term in office, the power of the landowners over the rural peasantry increased. He oversaw the rebuilding of parts of

Guatemala City

Guatemala City ( es, Ciudad de Guatemala), known locally as Guatemala or Guate, is the capital and largest city of Guatemala, and the most populous urban area in Central America. The city is located in the south-central part of the country, nest ...

on a grander scale, with wide, Parisian-style avenues. He oversaw Guatemala hosting the first "

Exposición Centroamericana

The Exposición Centroamericana (Central American Expo) was an industrial and cultural exposition that took place in Guatemala in 1897 and which was approved on 8 March 1894 by the National Assembly by Decree 253 by a suggestion made by presid ...

" ("Central American Fair") in 1897. During his second term, Barrios printed

bond

Bond or bonds may refer to:

Common meanings

* Bond (finance), a type of debt security

* Bail bond, a commercial third-party guarantor of surety bonds in the United States

* Chemical bond, the attraction of atoms, ions or molecules to form chemical ...

s to fund his ambitious plans, fueling

monetary inflation

Monetary inflation is a sustained increase in the money supply of a country (or currency area). Depending on many factors, especially public expectations, the fundamental state and development of the economy, and the transmission mechanism, it ...

and the rise of popular opposition to his regime.

His administration also worked on improving the roads, installing national and international telegraphs and introducing electricity to Guatemala City. Completing a transoceanic railway was a main objective of his government, with a goal to attract international investors at a time when the

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

was not yet built.

Manuel Estrada Cabrera regime (1898–1920)

After the assassination of general

José María Reina Barrios

José María Reyna Barrios (24 December 1854 – 8 February 1898) was President of Guatemala from 15 March 1892 until his death on 8 February 1898. He was born in San Marcos, Guatemala and was nicknamed ''Reynita'', the diminutive form, bec ...

on 8 February 1898, the Guatemalan cabinet called an emergency meeting to appoint a new successor, but declined to invite Estrada Cabrera to the meeting, even though he was the designated successor to the presidency. There are two different descriptions of how Cabrera was able to become president. The first states that Cabrera entered the cabinet meeting "with pistol drawn" to assert his entitlement to the presidency, while the second states that he showed up unarmed to the meeting and demanded the presidency by virtue of being the designated successor.

The first civilian Guatemalan head of state in over 50 years, Estrada Cabrera overcame resistance to his regime by August 1898 and called for elections in September, which he won handily. In 1898 the legislature convened for the election of President Estrada Cabrera, who triumphed thanks to the large number of soldiers and policemen who went to vote in civilian clothes and to the large number of illiterate family that they brought with them to the polls.

One of Estrada Cabrera's most famous and most bitter legacies was allowing the entry of the

United Fruit Company

The United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) was an American multinational corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. The company was formed in 1899 fro ...

(UFCO) into the Guatemalan economic and political arena. As a member of the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, he sought to encourage development of the nation's infrastructure of

highway

A highway is any public or private road or other public way on land. It is used for major roads, but also includes other public roads and public tracks. In some areas of the United States, it is used as an equivalent term to controlled-access ...

s,

railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s, and

sea port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

s for the sake of expanding the export economy. By the time Estrada Cabrera assumed the presidency there had been repeated efforts to construct a railroad from the major port of

Puerto Barrios

Puerto Barrios () is a city in Guatemala, located within the Gulf of Honduras. The city is located on Bahia de Amatique. Puerto Barrios is the departmental seat of Izabal department and is the administrative seat of Puerto Barrios municipality.

...

to the capital, Guatemala City. Owing to lack of funding exacerbated by the collapse of the internal coffee trade, the railway fell short of its goal. Estrada Cabrera decided, without consulting the legislature or judiciary, that striking a deal with the UFCO was the only way to finish the railway. Cabrera signed a contract with UFCO's

Minor Cooper Keith

Minor Cooper Keith (19 January 1848 – 14 June 1929) was an American businessman whose railroad, commercial agriculture, and cargo liner enterprises had a major impact on the national economies of the Central American countries, as well as on th ...

in 1904 that gave the company tax exemptions, land grants, and control of all railroads on the Atlantic side.

Estrada Cabrera often employed brutal methods to assert his authority. Right at the beginning of his first presidential period he started prosecuting his political rivals and soon established a well-organized web of spies. One American ambassador returned to the United States after he learned the dictator had given orders to poison him. Former president

Manuel Barillas

Manuel Lisandro Barillas Bercián (17 January 1845 – 7 April 1907) was a Guatemalan general and acting president of Guatemala from 6 April 1885 to 15 March 1886 and President from 16 March 1886 to 15 March 1892. He was born in Quetzaltenango, ...

was stabbed to death in Mexico City. Estrada Cabrera responded violently to workers' strikes against UFCO. In one incident, when UFCO went directly to Estrada Cabrera to resolve a strike (after the armed forces refused to respond), the president ordered an armed unit to enter a workers' compound. The forces "arrived in the night, firing indiscriminately into the workers' sleeping quarters, wounding and killing an unspecified number."

In 1906 Estrada faced serious revolts against his rule; the rebels were supported by the governments of some of the other

Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

n nations, but Estrada succeeded in putting them down. Elections were held by the people against the will of Estrada Cabrera and thus he had the president-elect murdered in retaliation. In 1907 Estrada narrowly survived an assassination attempt when a bomb exploded near his carriage. It has been suggested that the extreme despotic characteristics of Estrada did not emerge until after an attempt on his life in 1907.

Guatemala City

Guatemala City ( es, Ciudad de Guatemala), known locally as Guatemala or Guate, is the capital and largest city of Guatemala, and the most populous urban area in Central America. The city is located in the south-central part of the country, nest ...

was badly damaged in the

1917 Guatemala earthquake

The 1917 Guatemala earthquakes were a sequence of tremors that lasted from 17 November 1917 through 24 January 1918. They gradually increased in intensity until they almost completely destroyed Guatemala City and severely damaged the ruins in ...

.

Estrada Cabrera continued in power until forced to resign after new revolts in 1920. By that time his power had declined drastically and he was reliant upon the loyalty of a few generals. While the United States threatened intervention if he was removed through revolution, a bipartisan coalition came together to remove him from the presidency. He was removed from office after the national assembly charged that he was mentally incompetent, and appointed

Carlos Herrera

Carlos Herrera y Luna (26 October 1856 – 3 July 1930) was a Guatemalan politician who served as acting President of Guatemala from 30 March 1920 to 15 September 1920, and President of Guatemala from 16 September 1920 until 10 December 1921.

...

in his place on 8 April 1920.

Guatemala joined with El Salvador and Honduras in the Federation of Central America from 9 September 1921 until 14 January 1922.

Carlos Herrera served as President of Guatemala from 1920 until 1921. He was succeeded by

José María Orellana

José María Orellana Pinto (11 July 1872 – 26 September 1926) was a Guatemalan political and military leader. He was chief of staff of President Manuel Estrada Cabrera and President of Guatemala between 1921 and 1926, after overthrowing Conse ...

, who served from 1921 until 1926.

Lázaro Chacón González then served until 1931.

Jorge Ubico regime (1931–1944)

The

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

began in 1929 and badly damaged the Guatemalan economy, causing a rise in

unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for Work (human activity), w ...

, and leading to unrest among workers and laborers. Afraid of a popular revolt, the Guatemalan landed elite lent their support to

Jorge Ubico

Jorge Ubico Castañeda (10 November 1878 – 14 June 1946), nicknamed Number Five or also Central America's Napoleon, was a Guatemalan dictator. A general in the Guatemalan army, he was elected to the presidency in 1931, in an election where ...

, who had become well known for "efficiency and cruelty" as a provincial governor. Ubico won the election that followed in 1931, in which he was the only candidate. After his election his policies quickly became authoritarian. He replaced the system of debt

peon

Peon (English , from the Spanish ''peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over emp ...

age with a brutally enforced

vagrancy

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, temporar ...

law, requiring all men of working age who did not own land to work a minimum of 100 days of hard labor. His government used unpaid Indian labor to build roads and railways. Ubico also froze wages at very low levels, and passed a law allowing land-owners complete immunity from prosecution for any action they took to defend their property, an action described by historians as legalizing murder. He greatly strengthened the police force, turning it into one of the most efficient and ruthless in Latin America. He gave them greater authority to shoot and imprison people suspected of breaking the labor laws. These laws created tremendous resentment against him among agricultural laborers. The government became highly militarized; under his rule, every provincial governor was a general in the army.

Ubico continued his predecessor's policy of making massive concessions to the

United Fruit Company

The United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) was an American multinational corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. The company was formed in 1899 fro ...

, often at a cost to Guatemala. He granted the company of public land in exchange for a promise to build a port, a promise he later waived. Since its entry into Guatemala, the United Fruit Company had expanded its land-holdings by displacing farmers and converting their farmland to

banana plantation

A banana plantation is a commercial agricultural facility found in tropical climates where bananas are grown.

Geographic distribution

Banana plants may grow with varying degrees of success in diverse climatic conditions, but

commercial banana p ...

s. This process accelerated under Ubico's presidency, with the government doing nothing to stop it. The company received import duty and real estate tax exemptions from the government and controlled more land than any other individual or group. It also controlled the sole railroad in the country, the sole facilities capable of producing electricity, and the port facilities at

Puerto Barrios

Puerto Barrios () is a city in Guatemala, located within the Gulf of Honduras. The city is located on Bahia de Amatique. Puerto Barrios is the departmental seat of Izabal department and is the administrative seat of Puerto Barrios municipality.

...

on the Atlantic coast.

Ubico saw the United States as an ally against the supposed communist threat of Mexico, and made efforts to gain its support. When the US

declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, i ...

against Germany in 1941, Ubico acted on American instructions and arrested all people in Guatemala of

German descent

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

. He also permitted the US to establish an air base in Guatemala, with the stated aim of protecting the

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

. However, Ubico was an admirer of European

fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

s, such as

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

and

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, and considered himself to be "another

Napoleon