Grus grus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The common crane (''Grus grus''), also known as the Eurasian crane, is a

This species is found in the northern parts of Europe and across the

This species is found in the northern parts of Europe and across the

In Europe, the common crane predominantly breeds in boreal and taiga forest and mixed forests, from an elevation of sea-level to . In northern

In Europe, the common crane predominantly breeds in boreal and taiga forest and mixed forests, from an elevation of sea-level to . In northern

This species usually lays eggs in May, though seldom will do so earlier or later. Like most cranes, this species displays indefinite monogamous pair bonds. If one mate dies, a crane may attempt to court a new mate the following year. Although a pair may be together for several years, the courtship rituals of the species are enacted by every pair each spring. The dancing of common cranes has complex, social meanings and may occur at almost any time of year. Dancing may include bobs, bows, pirouettes, and stops, as in various crane species. Aggressive displays may include ruffled wing feathers, throwing vegetation in the air and pointing the bare red patch on their heads at each other. Courtship displays begin with a male following the female in a stately, march-like walk. The unison call, consists of the female holding her head up and gradually lowering down as she calls out. The female calls out a high note and then the male follows with a longer scream in a similar posture. Copulation consists of a similar, dramatic display.

This species usually lays eggs in May, though seldom will do so earlier or later. Like most cranes, this species displays indefinite monogamous pair bonds. If one mate dies, a crane may attempt to court a new mate the following year. Although a pair may be together for several years, the courtship rituals of the species are enacted by every pair each spring. The dancing of common cranes has complex, social meanings and may occur at almost any time of year. Dancing may include bobs, bows, pirouettes, and stops, as in various crane species. Aggressive displays may include ruffled wing feathers, throwing vegetation in the air and pointing the bare red patch on their heads at each other. Courtship displays begin with a male following the female in a stately, march-like walk. The unison call, consists of the female holding her head up and gradually lowering down as she calls out. The female calls out a high note and then the male follows with a longer scream in a similar posture. Copulation consists of a similar, dramatic display.

The nesting territory of common cranes is variable and is based on the local habitat. It can range in size from variously . In common with sandhill cranes (and no other crane species), common cranes "paint" their bodies with mud or decaying vegetation, apparently in order to blend into their nesting environment. The nest is either in or very near shallow water, often with dense shore vegetation nearby, and may be used over several years. The size and placement of the nest varies considerably over the range, with Arctic birds building relatively small nests. In Sweden, an average nest is around across.

The clutch of the common crane usually contains two eggs, with seldom one laid and, even more rarely, 3 or 4. If a clutch is lost early in incubation, the cranes may be able to lay another one within a couple of weeks. The incubation period is around 30 days and is done primarily by the female but occasionally by both sexes. If humans approach the nest both parents may engage in a

The nesting territory of common cranes is variable and is based on the local habitat. It can range in size from variously . In common with sandhill cranes (and no other crane species), common cranes "paint" their bodies with mud or decaying vegetation, apparently in order to blend into their nesting environment. The nest is either in or very near shallow water, often with dense shore vegetation nearby, and may be used over several years. The size and placement of the nest varies considerably over the range, with Arctic birds building relatively small nests. In Sweden, an average nest is around across.

The clutch of the common crane usually contains two eggs, with seldom one laid and, even more rarely, 3 or 4. If a clutch is lost early in incubation, the cranes may be able to lay another one within a couple of weeks. The incubation period is around 30 days and is done primarily by the female but occasionally by both sexes. If humans approach the nest both parents may engage in a

In

In

File:Common Cranes (Grus grus) at Sultanpur I Picture 076.jpg, Flock in flight

File:Flickr - Rainbirder - Eurasian Crane (Grus grus) (cropped).jpg, Individual in flight

File:Common Cranes (Grus grus)- Adults & Immatures at Bharatpur I IMG 5659.jpg, Adults and immatures at

Eurasian Crane

at th

International Crane Foundation

Eurasian Crane (''Grus grus'')

from ''Cranes of the World'' (1983) by

Découverte des grues cendrées

a

Reportages Aube Nature

by Klaus Nigge

Observing cranes without disturbing them

* * * * {{Authority control Grus (genus) Birds of Eurasia Birds of Russia Birds of North Africa Birds described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Articles containing video clips

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

of the family Gruidae, the cranes

Crane or cranes may refer to:

Common meanings

* Crane (bird), a large, long-necked bird

* Crane (machine), industrial machinery for lifting

** Crane (rail), a crane suited for use on railroads

People and fictional characters

* Crane (surname), ...

. A medium-sized species, it is the only crane commonly found in Europe besides the demoiselle crane

The demoiselle crane (''Grus virgo'') is a species of crane found in central Eurosiberia, ranging from the Black Sea to Mongolia and North Eastern China. There is also a small breeding population in Turkey. These cranes are migratory birds. Bird ...

(''Grus virgo'') and the Siberian crane

The Siberian crane (''Leucogeranus leucogeranus''), also known as the Siberian white crane or the snow crane, is a bird of the family Gruidae, the cranes. They are distinctive among the cranes: adults are nearly all snowy white, except for their ...

(''Leucogeranus leucogeranus''). Along with the sandhill

A sandhill is a type of ecological community or xeric wildfire-maintained ecosystem. It is not the same as a sand dune. It features very short fire return intervals, one to five years. Without fire, sandhills undergo ecological succession and be ...

(''Antigone canadensis'') and demoiselle cranes and the brolga

The brolga (''Antigone rubicunda''), formerly known as the native companion, is a bird in the crane family. It has also been given the name Australian crane, a term coined in 1865 by well-known ornithologist John Gould in his '' Birds of Austra ...

(''Antigone rubicunda''), it is one of only four crane species not currently classified as threatened with extinction or conservation dependent on the species level. Despite the species' large numbers, local extinctions and extirpations have taken place in part of its range, and an ongoing reintroduction project is underway in the United Kingdom.

Taxonomy

The first formal description of the common crane was by the Swedish naturalistCarl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

in 1758 in the tenth edition of his ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial nom ...

'' under the binomial name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

''Ardea grus''. The current genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial n ...

''Grus'' was erected by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson

Mathurin Jacques Brisson (; 30 April 1723 – 23 June 1806) was a French zoologist and natural philosopher.

Brisson was born at Fontenay-le-Comte. The earlier part of his life was spent in the pursuit of natural history; his published wo ...

in 1760. ''Grus'' is the Latin word for a "crane".

Description

The common crane is a large, stately bird and a medium-sized crane. It is long with a wingspan. The body weight can range from , with the nominate subspecies averaging around and the eastern subspecies (''G. g. lilfordi'') averaging . Among standard measurements, the wing chord is long, the tarsus is and the exposed culmen is . Males are slightly heavier and larger than females, with weight showing the largestsexual size dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most anim ...

, followed by wing, central toe, and head length in adults and juveniles.

This species is slate-grey overall. The forehead and lores Lores may refer to:

* Lore (anatomy)

* Lores (surname) Lores is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Enrique Lores (born 1964/65), Spanish business executive

*Horacio Lores, Argentine politician

*Julio Lores (1908–1947), Peruvi ...

are blackish with a bare red crown and a white streak extending from behind the eyes to the upper back. The overall colour is darkest on the back and rump and palest on the breast and wings. The primaries, the tips of secondaries, the alula

The alula , or bastard wing, (plural ''alulae'') is a small projection on the anterior edge of the wing of modern birds and a few non-avian dinosaurs. The word is Latin and means "winglet"; it is the diminutive of ''ala'', meaning "wing". The ...

, the tip of the tail, and the edges of upper tail coverts are all black and the greater coverts droop into explosive plumes. This combination of colouration ultimately distinguishes it from similar species in Asia, like the hooded (''G. monacha'') and black-necked crane

The black-necked Crane (''Grus nigricollis'') is a medium-sized crane in Asia that breeds on the Tibetan Plateau and remote parts of India and Bhutan. It is 139 cm (55 in) long with a 235 cm (7.8 ft) wingspan, and it weighs 5 ...

s (''G. nigricollis''). The juvenile has yellowish-brown tips to its body feathers and lacks the drooping wing feathers and the bright neck pattern of the adult, and has a fully feathered crown. Every two years, before migration, the adult common crane undergoes a complete moult, remaining flightless for six weeks, until the new feathers grow.

It has a loud trumpeting call, given in flight and display. The call is piercing and can be heard from a considerable distance. It has a dancing display, leaping with wings uplifted, described in detail below.

Distribution

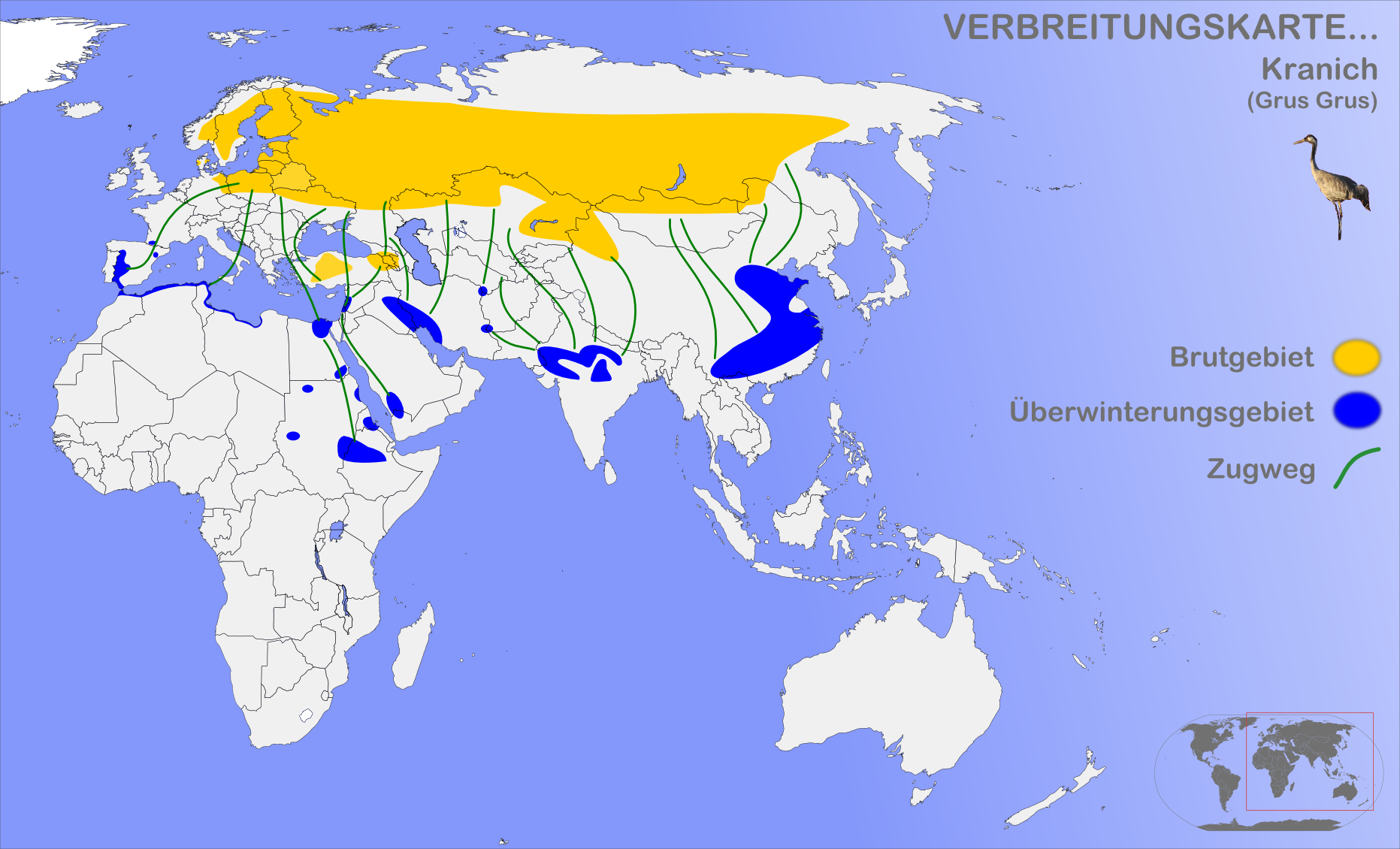

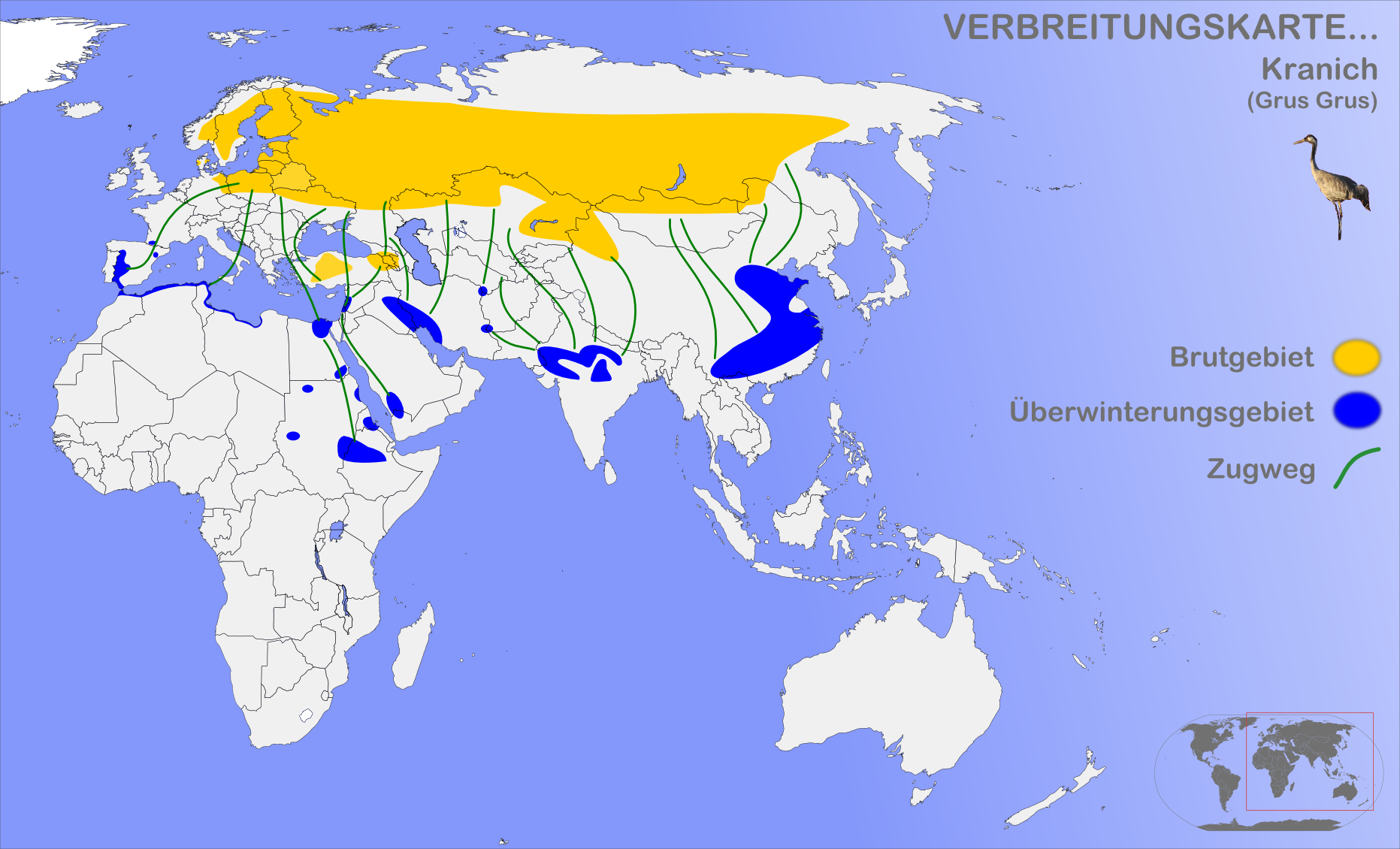

This species is found in the northern parts of Europe and across the

This species is found in the northern parts of Europe and across the Palearctic

The Palearctic or Palaearctic is the largest of the eight biogeographic realms of the Earth. It stretches across all of Eurasia north of the foothills of the Himalayas, and North Africa.

The realm consists of several bioregions: the Euro-Si ...

to Siberia. Formerly the species was spread as far west as Ireland, but about 200 years ago, it became extinct there. However, it has since started to return to Ireland naturally and there are now plans to help it return to Ireland on a greater scale. The common crane is an uncommon breeder in southern Europe, smaller numbers breeding in Greece, former-Yugoslavia, Romania, the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Larger breeding populations can be found in Scandinavia, especially Finland and Sweden. The heart of the breeding population for the species is in Russia, however, where possibly up to 100,000 cranes of this species can be found seasonally. It is distributed as a breeder from Ukraine to the Chukchi Peninsula in Russia. The breeding population extends as far south as Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym "Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East ( Outer ...

but almost the entire Asian breeding population is restricted to Russia. Approximately 48-50 breeding pairs exist in the UK, with population centres in Somerset and Norfolk. In May 2021, ecologists in Ireland got excited and optimistic that a pair of common cranes, which have arrived in the midlands, will become the first to breed there in over 300 years.

The species is a long distance migrant predominantly wintering in northern Africa. Autumn migration is from August to October in the breeding areas, but from late October to early December at the wintering sites. Spring migration starts in February at wintering sites up to early March, but from March through May at the breeding areas. Migration phenology of common cranes is changing due to climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

. Important staging areas occur anywhere from Sweden, The Netherlands and Germany to China (with a large one around the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad s ...

) and many thousand cranes can be seen in one day in the Autumn. Some birds winter in southern Europe, including Portugal, Spain and France. Most eastern common cranes winter in the river valleys of Sudan, Ethiopia, Tunisia and Eritrea with smaller numbers in Turkey, northern Israel, Iraq and parts of Iran. The third major wintering region is in the northern half of Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India ...

, including Pakistan. Minimal wintering also occurs in Burma, Vietnam and Thailand. Lastly, they winter in eastern China, where they are often the most common crane (outnumbering black-necked cranes ten-to-one). Migrating flocks fly in a "V" formation.

It is a rare visitor to Japan and Korea, mostly blown over from the Chinese wintering population, and is a rare vagrant to western North America, where birds are occasionally seen with flocks of migrating sandhill crane

The sandhill crane (''Antigone canadensis'') is a species of large crane of North America and extreme northeastern Siberia. The common name of this bird refers to habitat like that at the Platte River, on the edge of Nebraska's Sandhills on th ...

s.

Habitat

In Europe, the common crane predominantly breeds in boreal and taiga forest and mixed forests, from an elevation of sea-level to . In northern

In Europe, the common crane predominantly breeds in boreal and taiga forest and mixed forests, from an elevation of sea-level to . In northern climes

The climes (singular ''clime''; also ''clima'', plural ''climata'', from Greek κλίμα ''klima'', plural κλίματα ''klimata'', meaning "inclination" or "slope") in classical Greco-Roman geography and astronomy were the divisions of ...

, it breeds in treeless moors, on bogs, or on dwarf heather habitats, usually where small lakes or pools are also found. In Sweden, breeders are usually found in small, swampy openings amongst pine forests, while in Germany, marshy wetlands are used. Breeding habitat used in Russia are similar, though they can be found nesting in less likely habitat such as steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslan ...

and even semi-desert, so long as water is near. Primarily, the largest number of common cranes are found breeding in wooded swamps, bogs and wetlands and seem to require quiet, peaceful environs with minimal human interference. They occur at low density as breeders even where common, typically ranging from 1 to 5 pairs per .

In winter, this species moves to flooded areas, shallow sheltered bays, and swampy meadows. During the flightless moulting period there is a need for shallow waters or high reed cover for concealment. Later, after the migration period, the birds winter regularly in open country, often on cultivated lands and sometimes also in savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

-like areas, for example on the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

.

Behaviour

Diet

The common crane isomnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nut ...

, as are all cranes. It largely eats plant matter, including root

In vascular plants, the roots are the organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often below the sur ...

s, rhizomes, tuber

Tubers are a type of enlarged structure used as storage organs for nutrients in some plants. They are used for the plant's perennation (survival of the winter or dry months), to provide energy and nutrients for regrowth during the next growin ...

s, stem

Stem or STEM may refer to:

Plant structures

* Plant stem, a plant's aboveground axis, made of vascular tissue, off which leaves and flowers hang

* Stipe (botany), a stalk to support some other structure

* Stipe (mycology), the stem of a mushr ...

s, leaves, fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

s and seed

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiosper ...

s. They also commonly eat, when available, pond-weeds, heath berries, pea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

s, potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Un ...

es, olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'', meaning 'European olive' in Latin, is a species of small tree or shrub in the family Oleaceae, found traditionally in the Mediterranean Basin. When in shrub form, it is known as ''Olea europaea'' ...

s, acorn

The acorn, or oaknut, is the nut of the oaks and their close relatives (genera '' Quercus'' and ''Lithocarpus'', in the family Fagaceae). It usually contains one seed (occasionally

two seeds), enclosed in a tough, leathery shell, and bo ...

s, cedarnuts and pods of peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible Seed, seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics, important to both small ...

s. Notably amongst the berries consumed, the cranberry

Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the subgenus ''Oxycoccus'' of the genus '' Vaccinium''. In Britain, cranberry may refer to the native species '' Vaccinium oxycoccos'', while in North America, cranber ...

, is possibly named after the species.

Animal foods become more important during the summer breeding season and may be the primary food source at that time of year, especially while regurgitating to young. Their animal foods are insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s, especially dragonflies

A dragonfly is a flying insect belonging to the infraorder Anisoptera below the order Odonata. About 3,000 extant species of true dragonfly are known. Most are tropical, with fewer species in temperate regions. Loss of wetland habitat threaten ...

, and also snail

A snail is, in loose terms, a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class G ...

s, earthworm

An earthworm is a terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. They exhibit a tube-within-a-tube body plan; they are externally segmented with corresponding internal segmentation; and they usually have setae on all segments. ...

s, crabs, spider

Spiders (order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species d ...

s, millipede

Millipedes are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derived from this feature. Each double-legged segment is a re ...

s, woodlice

A woodlouse (plural woodlice) is an isopod crustacean from the polyphyleticThe current consensus is that Oniscidea is actually triphyletic suborder Oniscidea within the order Isopoda. They get their name from often being found in old wood.

...

, amphibians, rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are roden ...

s, and small bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s.

Common cranes may either forage on land or in shallow water, probing around with their bills for any edible organism. Although crops may locally be damaged by the species, they mostly consume waste grain in winter from previously harvested fields and so actually benefit farmers by cleaning fields for use in the following year. As with other cranes, all foraging (as well as drinking and roosting) is done in small groups, which may variously consist of pairs, family groups or winter flocks.

Breeding

This species usually lays eggs in May, though seldom will do so earlier or later. Like most cranes, this species displays indefinite monogamous pair bonds. If one mate dies, a crane may attempt to court a new mate the following year. Although a pair may be together for several years, the courtship rituals of the species are enacted by every pair each spring. The dancing of common cranes has complex, social meanings and may occur at almost any time of year. Dancing may include bobs, bows, pirouettes, and stops, as in various crane species. Aggressive displays may include ruffled wing feathers, throwing vegetation in the air and pointing the bare red patch on their heads at each other. Courtship displays begin with a male following the female in a stately, march-like walk. The unison call, consists of the female holding her head up and gradually lowering down as she calls out. The female calls out a high note and then the male follows with a longer scream in a similar posture. Copulation consists of a similar, dramatic display.

This species usually lays eggs in May, though seldom will do so earlier or later. Like most cranes, this species displays indefinite monogamous pair bonds. If one mate dies, a crane may attempt to court a new mate the following year. Although a pair may be together for several years, the courtship rituals of the species are enacted by every pair each spring. The dancing of common cranes has complex, social meanings and may occur at almost any time of year. Dancing may include bobs, bows, pirouettes, and stops, as in various crane species. Aggressive displays may include ruffled wing feathers, throwing vegetation in the air and pointing the bare red patch on their heads at each other. Courtship displays begin with a male following the female in a stately, march-like walk. The unison call, consists of the female holding her head up and gradually lowering down as she calls out. The female calls out a high note and then the male follows with a longer scream in a similar posture. Copulation consists of a similar, dramatic display.

The nesting territory of common cranes is variable and is based on the local habitat. It can range in size from variously . In common with sandhill cranes (and no other crane species), common cranes "paint" their bodies with mud or decaying vegetation, apparently in order to blend into their nesting environment. The nest is either in or very near shallow water, often with dense shore vegetation nearby, and may be used over several years. The size and placement of the nest varies considerably over the range, with Arctic birds building relatively small nests. In Sweden, an average nest is around across.

The clutch of the common crane usually contains two eggs, with seldom one laid and, even more rarely, 3 or 4. If a clutch is lost early in incubation, the cranes may be able to lay another one within a couple of weeks. The incubation period is around 30 days and is done primarily by the female but occasionally by both sexes. If humans approach the nest both parents may engage in a

The nesting territory of common cranes is variable and is based on the local habitat. It can range in size from variously . In common with sandhill cranes (and no other crane species), common cranes "paint" their bodies with mud or decaying vegetation, apparently in order to blend into their nesting environment. The nest is either in or very near shallow water, often with dense shore vegetation nearby, and may be used over several years. The size and placement of the nest varies considerably over the range, with Arctic birds building relatively small nests. In Sweden, an average nest is around across.

The clutch of the common crane usually contains two eggs, with seldom one laid and, even more rarely, 3 or 4. If a clutch is lost early in incubation, the cranes may be able to lay another one within a couple of weeks. The incubation period is around 30 days and is done primarily by the female but occasionally by both sexes. If humans approach the nest both parents may engage in a distraction display

Distraction displays, also known as diversionary displays, or paratrepsis are anti-predator behaviors used to attract the attention of an enemy away from something, typically the nest or young, that is being protected by a parent. Distraction disp ...

but known ground predators (including domestic dogs

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it is derived from the extinct Pleistocene wolf, and the modern wolf is the dog's nearest living relative. ...

(''Canis lupus familiaris'')) are physically attacked almost immediately.

New hatchlings are generally quite helpless but are able to crawl away from danger within a few hours, can swim soon after hatching and can run with their parents at 24 hours old. Chicks respond to danger by freezing, using their camouflaged brownish down to defend them beyond their fierce parents. Young chicks use their wings to stabilise them while running, while by 9 weeks of age they can fly short distances. The adult birds go through their postbreeding moult while caring for their young, rendering them flightless for about 5 to 6 weeks around the time the young also can't fly yet. According to figures of cranes wintering in Spain, around 48% birds have surviving young by the time they winter and around 18% are leading two young by winter. By the next breeding season, the previous years young often flock together. The age of sexual maturity in wild birds has been estimated at variously from 3 to 6 years of age.

Longevity

This species could live up to 30 or 40 years of age. But thedata

In the pursuit of knowledge, data (; ) is a collection of discrete values that convey information, describing quantity, quality, fact, statistics, other basic units of meaning, or simply sequences of symbols that may be further interpret ...

on longevity

The word " longevity" is sometimes used as a synonym for "life expectancy" in demography. However, the term ''longevity'' is sometimes meant to refer only to especially long-lived members of a population, whereas ''life expectancy'' is always d ...

(43 years) and life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

(12 years, N=7 cranes) were published with captive cranes. Common cranes living in the wild must show shorter lives. Successful breeders, the best subjects in the population, are guessed to live on average 12 years. Unsuccessful breeding cranes, therefore, may have shorter lives. Elementary survival analysis

Survival analysis is a branch of statistics for analyzing the expected duration of time until one event occurs, such as death in biological organisms and failure in mechanical systems. This topic is called reliability theory or reliability analysi ...

with the Euring database reports a life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

at birth (LEB) of c. 5 years. This LEB of 5 years was similar to that estimated for other crane species, as for example the Florida Sandhill cranes

The sandhill crane (''Antigone canadensis'') is a species of large crane of North America and extreme northeastern Siberia. The common name of this bird refers to habitat like that at the Platte River, on the edge of Nebraska's Sandhills on th ...

(''G. canadensis'') (LEB = 7 years). Reports of tagged common cranes have increased rapidly in the last decades. Therefore, longevity

The word " longevity" is sometimes used as a synonym for "life expectancy" in demography. However, the term ''longevity'' is sometimes meant to refer only to especially long-lived members of a population, whereas ''life expectancy'' is always d ...

and life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

at birth of wild common cranes will be updated.

Sociality

The common crane is a fairly social bird while not breeding. Flocks of up to 400 birds may be seen flying together during migration. Staging sites, where migrating birds gather to rest and feed in the middle of their migration, may witness thousands of cranes gathering at once. However, the flocks of the species are not stable social units but rather groups that ensure greater safety in numbers and collectively draw each other's attention to ideal foraging and roosting sites. Possibly due to a longer molt, younger and non-breeding cranes are usually the earliest fall migrants and may band together at that time of year. During these migratory flights, common cranes have been known to fly at altitudes of up to , one of the highest of any species of bird, second only to the Ruppell's Griffin Vulture. Cranes use a kleptoparasitic strategy to recover from temporary reductions in feeding rate, particularly when the rate is below the threshold of intake necessary for survival. Accumulated intake of common cranes during daytime at a site of stopover and wintering shows a typical anti-sigmoid shape, with greatest increases of intake after dawn and before dusk.Interspecies interactions

There are few natural predators of adult cranes, althoughwhite-tailed eagle

The white-tailed eagle (''Haliaeetus albicilla'') is a very large species of sea eagle widely distributed across temperate Eurasia. Like all eagles, it is a member of the family Accipitridae (or accipitrids) which includes other diurnal rapto ...

(''Haliaeetus albicilla''), Bonelli's eagle

The Bonelli's eagle (''Aquila fasciata'') is a large bird of prey. The common name of the bird commemorates the Italian ornithologist and collector Franco Andrea Bonelli. Bonelli is credited with gathering the type specimen, most likely from an ...

s (''Aquila fasciata'') and golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known birds ...

s (''Aquila chrysaetos'') are a potential predatory threat to common cranes of all ages. The crane has been known to counterattack eagles both on the land and in mid-flight, using their bill as a weapon and kicking with their feet. Common cranes were additionally recorded as prey for Eurasian eagle-owl

The Eurasian eagle-owl (''Bubo bubo'') is a species of eagle-owl that resides in much of Palearctic, Eurasia. It is also called the Uhu and it is occasionally abbreviated to just the eagle-owl in Europe. It is one of the largest species of owl, ...

s (''Bubo bubo'') in the Ukok Plateau

Ukok Plateau is a plateau covered by grasslands located in southwestern Siberia, in the Altai Mountains region of Russia near the borders with China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. The plateau is recognized as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site ent ...

of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

. Mammals such as wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species is ...

(''Sus scrofa''), wolverine

The wolverine (), (''Gulo gulo''; ''Gulo'' is Latin for " glutton"), also referred to as the glutton, carcajou, or quickhatch (from East Cree, ''kwiihkwahaacheew''), is the largest land-dwelling species of the family Mustelidae. It is a musc ...

(''Gulo gulo'') and red foxes (''Vulpes vulpes'') are attacked at the nest, as they are potential predators. When facing off against mammals, cranes jab with their bill, hit with their wings and kick with their feet. The cranes nimbly avoid strikes against themselves by jumping into the air. It is probable that they are threatened by a wider range of large mammalian predators as is the black-necked crane but these have not yet been recorded. Herbivorous mammals such as red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of wes ...

(''Cervus elaphus'') may also be attacked at the nest, indicating the high aggressiveness of the birds while nesting. The determined attack of a parent crane often assures safety from predators, but occasional losses to predation are inevitable. The carrion crow

The carrion crow (''Corvus corone'') is a passerine bird of the family Corvidae and the genus ''Corvus'' which is native to western Europe and the eastern Palearctic.

Taxonomy and systematics

The carrion crow was one of the many species origi ...

(''Corvus corone'') is locally a successful predator of common cranes' eggs, trickily using distraction displays to steal them. Other species of ''Corvus

''Corvus'' is a widely distributed genus of medium-sized to large birds in the family Corvidae. It includes species commonly known as crows, ravens and rooks. The species commonly encountered in Europe are the carrion crow, the hooded crow ...

'' may also cause some loss of eggs, with common raven

The common raven (''Corvus corax'') is a large all-black passerine bird. It is the most widely distributed of all corvids, found across the Northern Hemisphere. It is a raven known by many names at the subspecies level; there are at least ...

s (''Corvus corax'') also taking some small chicks. Common cranes may loosely associate with any other crane in the genus ''Grus'' in migration or winter as well as greater white-fronted geese and bean geese

The taiga bean goose (''Anser fabalis'') is a goose that breeds in northern Europe and Asia. This and the tundra bean goose are recognised as separate species by the American Ornithological Society and the International Ornithologists' Union, bu ...

.

Status

The global population is 600,000 (2014 estimate) with the vast majority nesting inRussia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

and Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

. In some areas the breeding population appears to be increasing, such as in Sweden, whereas on the fringes of its range, it is often becoming rare to non-existent. In Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, it died out as a breeding species in the 18th century, but a flock of about 30 appeared in County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns ar ...

in November 2011, and a smaller flock a year later. It was additionally extirpated as a breeder from Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

around 1900, from Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

by 1952 and from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

by 1954. The recovering German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

breeding population of 8,000 pairs is still also a fraction of the size of the large numbers that once bred in the country. Poland has 15,000 breeding pairs, 50 pairs breed in the Czech Republic and 2009 was the first confirmed breeding in Slovakia.

In Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, the common crane became extirpated

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

in the 17th century, but a tiny population now breeds again in the Norfolk Broads

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North ...

and is slowly increasing and a reintroduction began in 2010 in the Somerset levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south are ...

. A total of 93 birds were released between 2010 and 2014 as part of the reintroduction effort, and there are now 180 resident birds in the UK. In 2016, a wild crane was born in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

for the first time in over 400 years.

The main threat to the species, and the primary reason for its decline in the Western Palearctic

The Western Palaearctic or Western Palearctic is part of the Palaearctic realm, one of the eight biogeographic realms dividing the Earth's surface. Because of its size, the Palaearctic is often divided for convenience into two, with Europe, North ...

, comes from habitat loss

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

and degradation

Degradation may refer to:

Science

* Degradation (geology), lowering of a fluvial surface by erosion

* Degradation (telecommunications), of an electronic signal

* Biodegradation of organic substances by living organisms

* Environmental degradatio ...

, as a result of dam construction, urbanisation

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly the ...

, agricultural expansion

Agricultural expansion describes the growth of agricultural land ( arable land, pastures, etc.) especially in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The agricultural expansion is often explained as a direct consequence of the global increase in food and e ...

, and drainage

Drainage is the natural or artificial removal of a surface's water and sub-surface water from an area with excess of water. The internal drainage of most agricultural soils is good enough to prevent severe waterlogging (anaerobic conditio ...

of wetlands

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free ( anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

. Although it has adapted to human settlement in many areas, nest disturbance, continuing changes in land use

Land use involves the management and modification of natural environment or wilderness into built environment such as settlements and semi-natural habitats such as arable fields, pastures, and managed woods. Land use by humans has a long his ...

, and collision with utility lines are still potential problems. Further threats may include persecution due to crop damage, pesticide poisoning

A pesticide poisoning occurs when pesticides, chemicals intended to control a pest, affect non-target organisms such as humans, wildlife, plant, or bees. There are three types of pesticide poisoning. The first of the three is a single and short ...

, egg collection, and hunting. The common crane is one of the species to which the ''Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds'' (AEWA

The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds, or African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement (AEWA) is an independent international treaty developed under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme's Convent ...

) applies.

Culture

1870

Events

January–March

* January 1

** The first edition of ''The Northern Echo'' newspaper is published in Priestgate, Darlington, England.

** Plans for the Brooklyn Bridge are completed.

* January 3 – Construction of the B ...

Józef Chełmoński

Józef Marian Chełmoński (November 7, 1849 – April 6, 1914) was a Polish painter of the Realism (art movement), realist school with roots in the historical and social context of the late Romanticism in Poland, Romantic period in partition ...

painted a picture

An image is a visual representation of something. It can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional, or somehow otherwise feed into the visual system to convey information. An image can be an artifact, such as a photograph or other two-dimensiona ...

: "Departure of Cranes" ( National Museum in Cracow)

In Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, despite being extinct for over 200 years, the common crane plays a very important part in Irish culture and folklore and so thus recent efforts to encourage it back to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

are received with much enthusiasm.

On 3 May 2021, a couple was spotted nesting at a side on a rewetted bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

The Kranich Museum in Hessenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV; ; nds, Mäkelborg-Vörpommern), also known by its anglicized name Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, is a state in the north-east of Germany. Of the country's sixteen states, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern ranks 14th in pop ...

, Germany, is dedicated to art and folklore related to the common crane.

The common crane is the sacred bird of the god Hephaestus

Hephaestus (; eight spellings; grc-gre, Ἥφαιστος, Hḗphaistos) is the Greek god of blacksmiths, metalworking, carpenters, craftsmen, artisans, sculptors, metallurgy, fire (compare, however, with Hestia), and volcanoes.Walter ...

, and it features heavily in the god's iconography.

In Indian states of Rajsthan and Gujarat this crane is described in lots of folk songs. Like- anewly married woman (whose husband has gone to far away place for earning) will sing a song to crane to take a message to her husband and request to tell him to come home early.

Gallery

Keoladeo National Park

Keoladeo National Park or Keoladeo Ghana National Park (formerly known as the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary) is a famous avifauna sanctuary in Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India, that hosts thousands of birds, especially during the winter season. Over 350 ...

, India

File:GreyCranesHula02.JPG, In flight at Israel ha-Hula

File:זריחה באגמון חולה בזמן נדידת העגורים.jpg, Common cranes in the Hula Valley

The Hula Valley ( he, עמק החולה, Romanization of Hebrew, translit. ''Emek Ha-Ḥula''; also transliterated as Huleh Valley, ar, سهل الحولة) is an agriculture, agricultural region in northern Israel with abundant fresh water, ...

in Israel

File:Common crane in flight.jpg, Common crane in flight

File:Flying common crane.jpg, Juvenile in flight

File:Common Crane from the Crossley ID Guide Britain and Ireland.jpg, ID composite

File:Zurawie Bobrowniki 03.jpg, Large flock of cranes near Bobrowniki, Poland

File:Common crane David Raju.jpg, From India

File:Common Crane AMSM6991.jpg, Adults in flight at Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary

Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary is a bird sanctuary located in Jamnagar district of Gujarat, India. About 300 species of migratory birds have been recorded here.

In 2022, on World Wetlands Day (2 February) it was declared as a Ramsar site.

Sanctuary

T ...

, Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the nin ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

File:Common Crane AMSM6984.jpg, Family group - adults and immatures - at Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary

Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary is a bird sanctuary located in Jamnagar district of Gujarat, India. About 300 species of migratory birds have been recorded here.

In 2022, on World Wetlands Day (2 February) it was declared as a Ramsar site.

Sanctuary

T ...

, Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the nin ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

File:Common Crane pairAMSM6949.jpg, Adults at Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary

Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary is a bird sanctuary located in Jamnagar district of Gujarat, India. About 300 species of migratory birds have been recorded here.

In 2022, on World Wetlands Day (2 February) it was declared as a Ramsar site.

Sanctuary

T ...

, Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the nin ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

File:Common Crane AMSM6923 CCRA.jpg, Immature at Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary

Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary is a bird sanctuary located in Jamnagar district of Gujarat, India. About 300 species of migratory birds have been recorded here.

In 2022, on World Wetlands Day (2 February) it was declared as a Ramsar site.

Sanctuary

T ...

, Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the nin ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

File:Trana (Grus grus) - Ystad -2022.jpg, A smal flock of Cranes in flight, Ystad

Ystad (; older da, Ysted) is a town and the seat of Ystad Municipality, in Scania County, Sweden. Ystad had 18,350 inhabitants in 2010. The settlement dates from the 11th century and has become a busy ferryport, local administrative centre, a ...

2022.

See also

*Cranes in Britain

Cranes are large, long-legged and long-necked birds of the order Gruiformes. Two species occur as wild birds in Great Britain: the common crane (''Grus grus''), a scarce migrant and very localised breeding resident currently being reintroduced t ...

* Lake Der-Chantecoq

Lake Der-Chantecoq (French: ''Lac du Der-Chantecoq'') is situated close to the commune of Saint-Dizier in the departments of Marne and Haute-Marne. It is the largest artificial lake in France, covering with 350 million m³ of water. The lake is ...

(migration stopover site)

* Hula Valley

The Hula Valley ( he, עמק החולה, Romanization of Hebrew, translit. ''Emek Ha-Ḥula''; also transliterated as Huleh Valley, ar, سهل الحولة) is an agriculture, agricultural region in northern Israel with abundant fresh water, ...

(migration stopover site)

* Lake Hornborga

Lake Hornborga ( sv, Hornborgasjön) is a lake in Västergötland in Sweden, famous for its many birds, in particular the many cranes that stay here temporarily during their annual migrations.

History

Lake Hornborga was created after the l ...

(migration stopover site)

References

External links

Eurasian Crane

at th

International Crane Foundation

Eurasian Crane (''Grus grus'')

from ''Cranes of the World'' (1983) by

Paul Johnsgard

Paul Austin Johnsgard (28 June 1931 – 28 May 2021) was an ornithologist, artist and emeritus professor at the University of Nebraska. His works include nearly fifty books including several monographs, principally about the waterfowl and crane ...

*

Découverte des grues cendrées

a

Reportages Aube Nature

by Klaus Nigge

Observing cranes without disturbing them

* * * * {{Authority control Grus (genus) Birds of Eurasia Birds of Russia Birds of North Africa Birds described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Articles containing video clips