Gruban V Booth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Gruban v Booth'' was a 1917 fraud case in England that generated significant publicity because the defendant, Frederick Handel Booth, was a

John Gruban was a German-born businessman, originally named Johann Wilhelm Gruban, who had come to England in 1893 to work for an engineering company, Haigh and Company.Hyde (1960) p.57 By 1913, he had turned the business from an almost-bankrupt company to a successful manufacturer of machine tools. At the outbreak of the

John Gruban was a German-born businessman, originally named Johann Wilhelm Gruban, who had come to England in 1893 to work for an engineering company, Haigh and Company.Hyde (1960) p.57 By 1913, he had turned the business from an almost-bankrupt company to a successful manufacturer of machine tools. At the outbreak of the

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

. Gruban was a German-born businessman who ran several factories that made tools for manufacturing munitions for the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. In an effort to find government contracts and money to expand his business, he contacted a businessman and MP, Frederick Handel Booth, who willingly promised both. Booth sought agreement from Gruban to have 10% of a large order's price, to be hidden from the rest of the Board; tricked Gruban into transferring the company, and had him interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

under wartime regulations to prevent a claim against him.

Gruban successfully appealed against his internment and as soon as he was freed brought Booth to court. The case was so popular that the involved barristers

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

found it physically difficult to get into the court each day because of the size of the crowds gathered outside. Although those on both sides were noted for their skill, the case went almost entirely one way, with the jury taking only ten minutes to find Booth guilty. It was one of the first noted cases of Patrick Hastings

Sir Patrick Gardiner Hastings (17 March 1880 – 26 February 1952) was an English barrister and politician noted for his long and highly successful career as a barrister and his short stint as Attorney General. He was educated at Charterhou ...

, and his victory in it led to him applying to become a King's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel ( post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister or ...

.

Background

John Gruban was a German-born businessman, originally named Johann Wilhelm Gruban, who had come to England in 1893 to work for an engineering company, Haigh and Company.Hyde (1960) p.57 By 1913, he had turned the business from an almost-bankrupt company to a successful manufacturer of machine tools. At the outbreak of the

John Gruban was a German-born businessman, originally named Johann Wilhelm Gruban, who had come to England in 1893 to work for an engineering company, Haigh and Company.Hyde (1960) p.57 By 1913, he had turned the business from an almost-bankrupt company to a successful manufacturer of machine tools. At the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, it was one of the first companies to produce machine tools to make munitions. That made Gruban a major player in a now-large market, and he attempted to raise £5,000 to expand his business. On independent advice, he contacted Frederick Handel Booth, a noted Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

who was chairman of the Yorkshire Iron and Coal Company and had led the government inquiry into the Marconi scandal

The Marconi scandal was a British political scandal that broke in mid-1912. Allegations were made that highly placed members of the Liberal government under the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith had profited by improper use of information about the gove ...

.Hyde (1960) p.58 When Gruban contacted Booth, Booth told him that he could do "more for our

Our or OUR may refer to:

* The possessive form of " we"

* Our (river), in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany

* Our, Belgium, a village in Belgium

* Our, Jura, a commune in France

* Office of Utilities Regulation (OUR), a government utility regulato ...

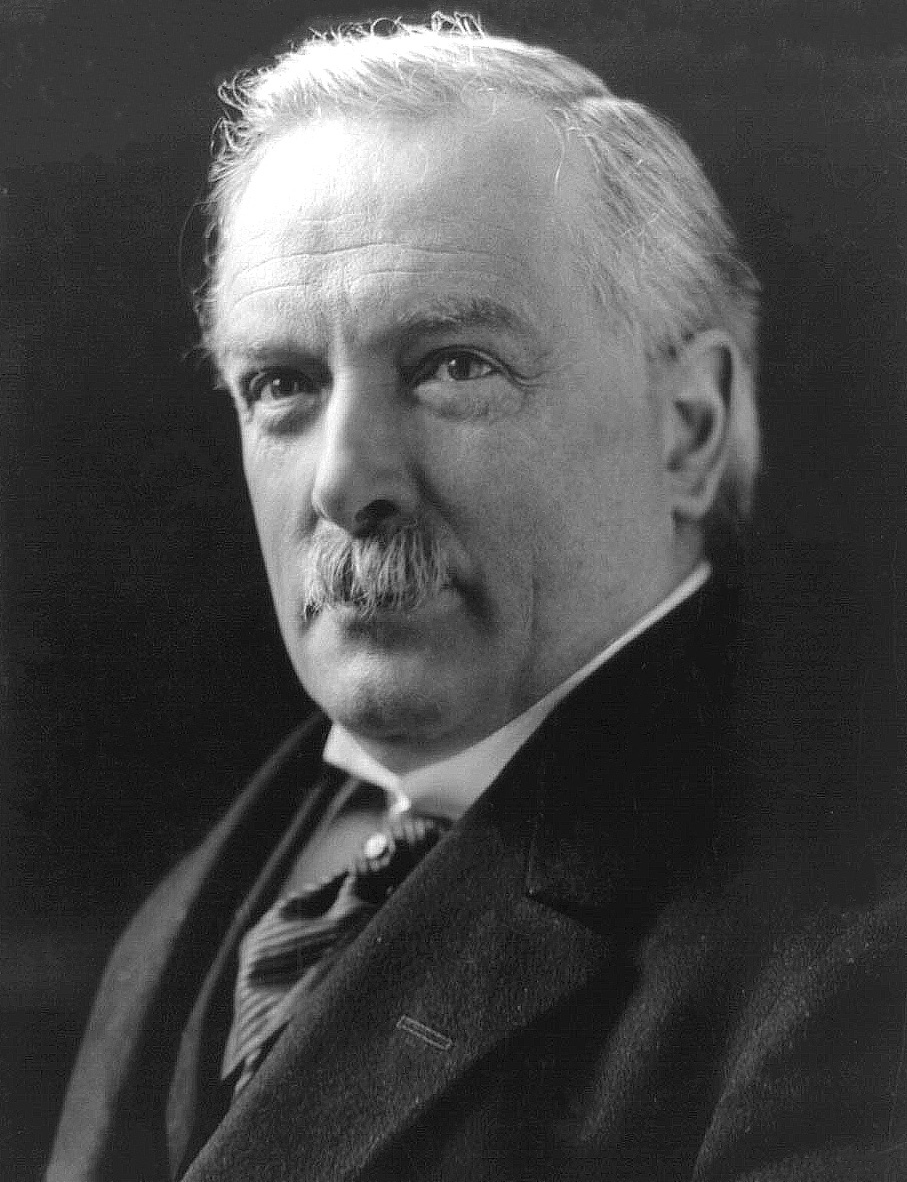

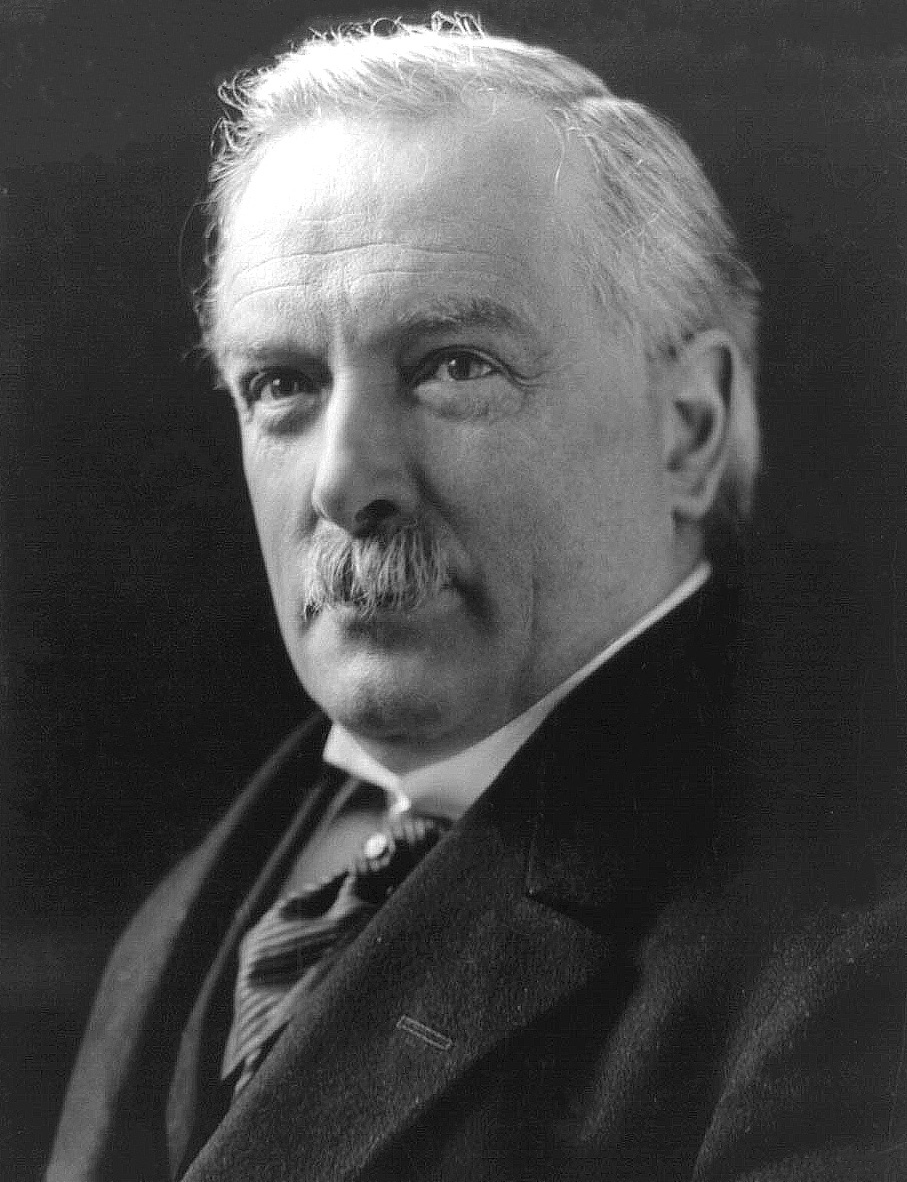

company than any man in England" and claimed that David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, then Minister of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis of ...

, and many other important government officials were close friends. With £3,500 borrowed from his brother-in-law, Booth immediately invested in Gruban's company.

The sinking of the ''RMS Lusitania

RMS ''Lusitania'' (named after the Roman province in Western Europe corresponding to modern Portugal) was a British ocean liner that was launched by the Cunard Line in 1906 and that held the Blue Riband appellation for the fastest Atlanti ...

'' in 1915 created a wave of anti-German sentiment, and Gruban worried that he would find it difficult to find government work because of his nationality and thick German accent. He again contacted Booth, who again claimed to be friends with Lloyd George and his secretary, Christopher Addison

Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison, (19 June 1869 – 11 December 1951), was a British medical doctor and politician. A member of the Liberal and Labour parties, he served as Minister of Munitions during the First World War and was late ...

. Booth also said that if Gruban put Booth on the Board of Directors

A board of directors (commonly referred simply as the board) is an executive committee that jointly supervises the activities of an organization, which can be either a for-profit or a nonprofit organization such as a business, nonprofit organiz ...

, he could "do with the Ministry of Munitions what I like". Gruban immediately made Booth the chairman of his company, and over three months took £400 on expenses. He then claimed that it was not enough money for the work he did and that he should get a semi-secret payment of 10% of the value of a contract, known as the "Birmingham Contract". The contract was worth £6,000, and Booth wrote a memo saying that he should have £580 or £600. Gruban refused. Booth threw the refusal in the wastepaper basket.Hyde (1960) p.59 From then on, Booth worked as hard as he could to undermine Gruban's position but outwardly appeared to be his friend.

Over the next few months, a series of complaints came from the Ministry of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis of ...

about Gruban's work and his German origins and ended in a written statement by Lloyd George's private secretary that it was "undesirable that any person of recent German nationality or association should at the present time be connected in an important capacity with any company or firm engaged in the production of munitions of war". Booth showed it to Gruban and told him that the only way to save the company and prevent Gruban being interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

was for him to transfer the ownership of the company to Booth.Hyde (1960) p.60 Gruban did so, and Booth immediately "came out in his true colours" by treating Gruban with contempt and refusing to help support his wife and family now that Gruban had no income. Eventually, Booth wrote to the Ministry of Munitions to say that Gruban had "taken leave of his senses", and the Ministry had Gruban interned.

Gruban appealed against the internment order and was called before a court, consisting of Mr Justice Younger and Mr Justice Sankey. After reviewing the facts of the case and the stories of Gruban and Booth, the judges ordered the immediate release of Gruban and recommended that he seek legal advice to see if he could regain control of his company. After he was released Gruban found a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

, W.J. Synott, who gave the case to Patrick Hastings

Sir Patrick Gardiner Hastings (17 March 1880 – 26 February 1952) was an English barrister and politician noted for his long and highly successful career as a barrister and his short stint as Attorney General. He was educated at Charterhou ...

.Hyde (1960) p.61

Trial

Hastings felt that his best chances lay in interviewingChristopher Addison

Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison, (19 June 1869 – 11 December 1951), was a British medical doctor and politician. A member of the Liberal and Labour parties, he served as Minister of Munitions during the First World War and was late ...

about his contact with Booth. As Addison was a government minister, he could be relied on to tell the truth. The case of ''Gruban v Booth'' opened on 7 May 1917 at the King's Bench Division

The King's Bench Division (or Queen's Bench Division when the monarch is female) of the High Court of Justice deals with a wide range of common law cases and has supervisory responsibility over certain lower courts.

It hears appeals on point ...

of the High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Courts of England and Wales, Senior Cou ...

in front of Mr Justice Coleridge. Patrick Hastings and Hubert Wallington represented Gruban, and Booth was represented by Rigby Swift

Sir Rigby Philip Watson Swift (7 June 1874 – 19 October 1937) was a British barrister, Member of Parliament and judge. Born into a legal family, Swift was educated at Parkfield School before taking up a place in his father's chambers and at ...

KC and Douglas Hogg

Douglas Martin Hogg, 3rd Viscount Hailsham, Baron Hailsham of Kettlethorpe (born 5 February 1945), is a British politician and barrister. A member of the Conservative Party he served in the Cabinet as Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Foo ...

. The trial attracted such public interest that on the final day that the barristers found it physically difficult to get through the crowds surrounding the Law Courts.

As counsel for the prosecution, Hastings was the first barrister to speak. In his opening speech to the jury, he criticised Booth for loving money rather than his country and said that one of the things that the English prided themselves on was fair play, and "no matter how loudly the defendant raises the cry of patriotism, I feel sure that your sense of fair play, gentlemen, will ensure a verdict that the defendant is unfit to sit in the House of Commons, as he has been guilty of fraud".Hyde (1960) p.62 Hastings then called Gruban to the witness stand and asked him to tell the jury what had happened. Gruban described how Booth had claimed to have influence over David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

. Gruban was then cross-examined by Rigby Swift.

Booth was then called to the witness stand and initially claimed that Gruban had claimed to be "a very powerful man" and that it had been a case of Gruban using his power to help Booth, not the other way around. He was still in the witness box when the court day ended, and the next morning, it was announced that Christopher Addison

Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison, (19 June 1869 – 11 December 1951), was a British medical doctor and politician. A member of the Liberal and Labour parties, he served as Minister of Munitions during the First World War and was late ...

had come to the court.Hyde (1960) p.63 The judge allowed Addison to give his testimony before they continued with Booth, and during a cross-examination by Hastings, Addison stated that he had not been advising Booth in any way and that "to say that Gruban's only chance of escape from internment was to hand over his shares to Mr Booth was a lie".

The final witness was Booth himself.Hyde (1960) p.64 He stated that he would never have asked for a 10% commission on the Birmingham contract and that he had never claimed that he could influence government ministers. Hastings showed the jury that both statements were lies, first by showing the piece of paper Booth had scribbled the "Birmingham contract" memo on and then by showing a telegram from Booth to Gruban in which Booth claimed that he " adalready spoken to a Cabinet Minister and high official".

In his summing up Mr Justice Coleridge was "on the whole unfavourable to Booth". He also pointed out that the German nationality of Gruban might prejudice the jury and asked it to "be sure that you permit no prejudice on their hand to disturb the balance of the scales of justice".Hyde (1960) p.67 The jury decided the case in only ten minutes, found Booth guilty and awarded Gruban £4,750.

References

Sources

*Further reading

* Hastings, Patrick, ''Cases in Court'', William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1949 {{good article 1917 in case law High Court of Justice cases 1917 in England Corruption in the United Kingdom English criminal case law Fraud in the United Kingdom 1917 in British law