Grub Street on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Until the early 19th century, Grub Street was a street close to

Until the early 19th century, Grub Street was a street close to

Grub Street was in Cripplegate ward, in the parish of

Grub Street was in Cripplegate ward, in the parish of  An early use of the land surrounding Grub Street was

An early use of the land surrounding Grub Street was

Publishing houses proliferated in Grub Street, and this, combined with the number of local garrets, meant that the area was an ideal home for hack writers. In ''The Preface'', when describing the harsh conditions a writer suffered, Tom Brown's self-parody referred to being "Block'd up in a Garret". Such contemporary views of the writer, in his inexpensive

Publishing houses proliferated in Grub Street, and this, combined with the number of local garrets, meant that the area was an ideal home for hack writers. In ''The Preface'', when describing the harsh conditions a writer suffered, Tom Brown's self-parody referred to being "Block'd up in a Garret". Such contemporary views of the writer, in his inexpensive

Other publications included the Whig ''

Other publications included the Whig ''

Although the Act had the unfortunate side-effect of closing down several newspapers, publishers used a weakness in the legislation which meant that newspapers of six pages (a half-sheet ''and'' a whole sheet) were only charged at the flat pamphlet rate of two shillings per sheet (regardless of the number of copies printed). Many publications thus expanded to six pages, filled the extra space with extraneous matter, and raised their prices to absorb the tax. Newspapers also used the extra space to introduce serials, hoping to hook readers into buying the next instalment. The periodical nature of the Newspaper allowed writers to develop their arguments over successive weeks, and the newspaper began to overtake the pamphlet as the primary medium for political news and comment.

By the 1720s 'Grub Street' had grown from a simple street name to a term for all manner of low-level publishing. The popularity of

Although the Act had the unfortunate side-effect of closing down several newspapers, publishers used a weakness in the legislation which meant that newspapers of six pages (a half-sheet ''and'' a whole sheet) were only charged at the flat pamphlet rate of two shillings per sheet (regardless of the number of copies printed). Many publications thus expanded to six pages, filled the extra space with extraneous matter, and raised their prices to absorb the tax. Newspapers also used the extra space to introduce serials, hoping to hook readers into buying the next instalment. The periodical nature of the Newspaper allowed writers to develop their arguments over successive weeks, and the newspaper began to overtake the pamphlet as the primary medium for political news and comment.

By the 1720s 'Grub Street' had grown from a simple street name to a term for all manner of low-level publishing. The popularity of  Newspapers and their authors were not yet completely free from state control. In 1763

Newspapers and their authors were not yet completely free from state control. In 1763

In 1716 the bookseller and

In 1716 the bookseller and

Although the street no longer exists in name (and modern construction has changed much of the area), the name continues to exist in modern use. Much of the area was destroyed by enemy bombing in

Although the street no longer exists in name (and modern construction has changed much of the area), the name continues to exist in modern use. Much of the area was destroyed by enemy bombing in

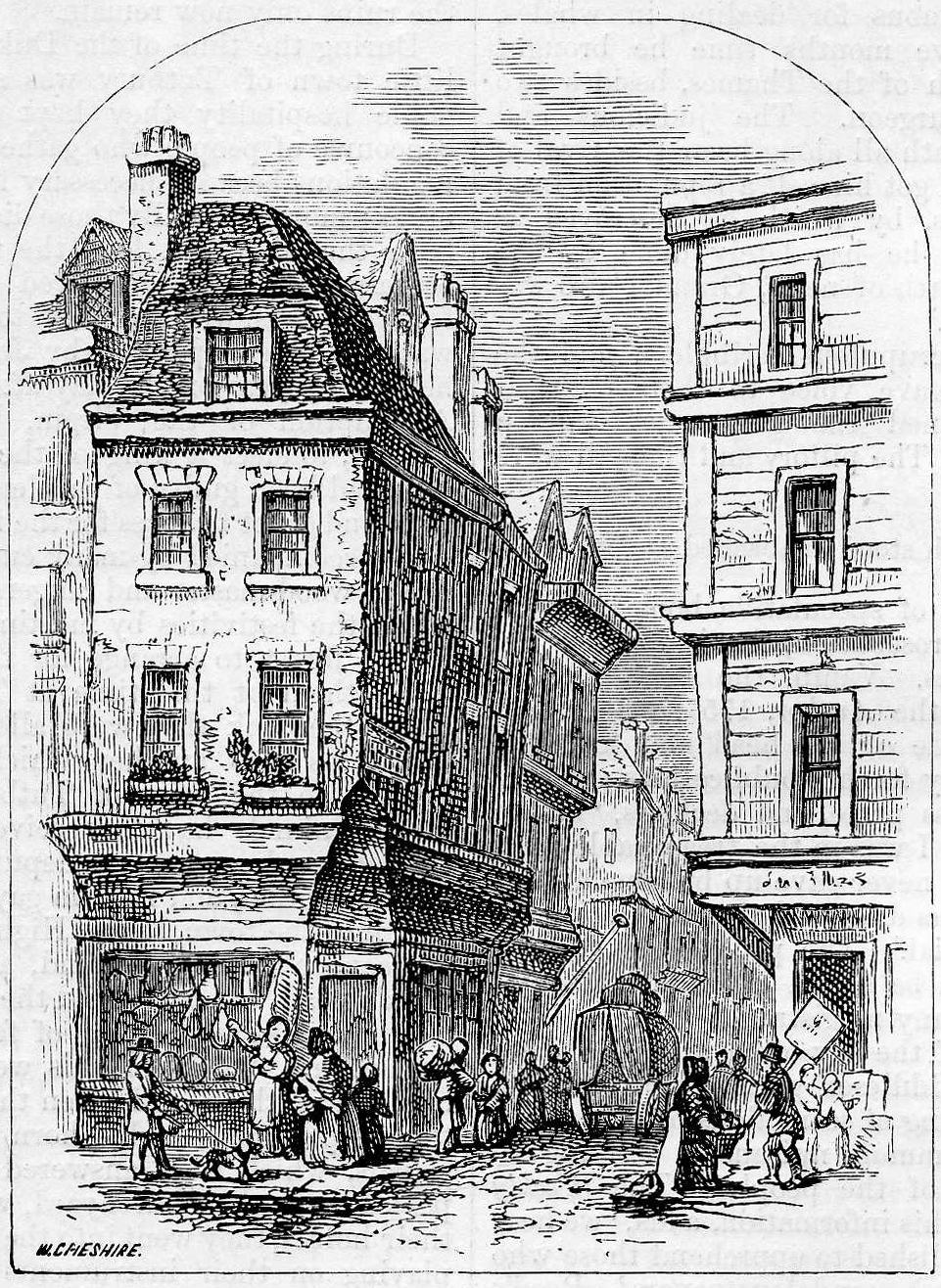

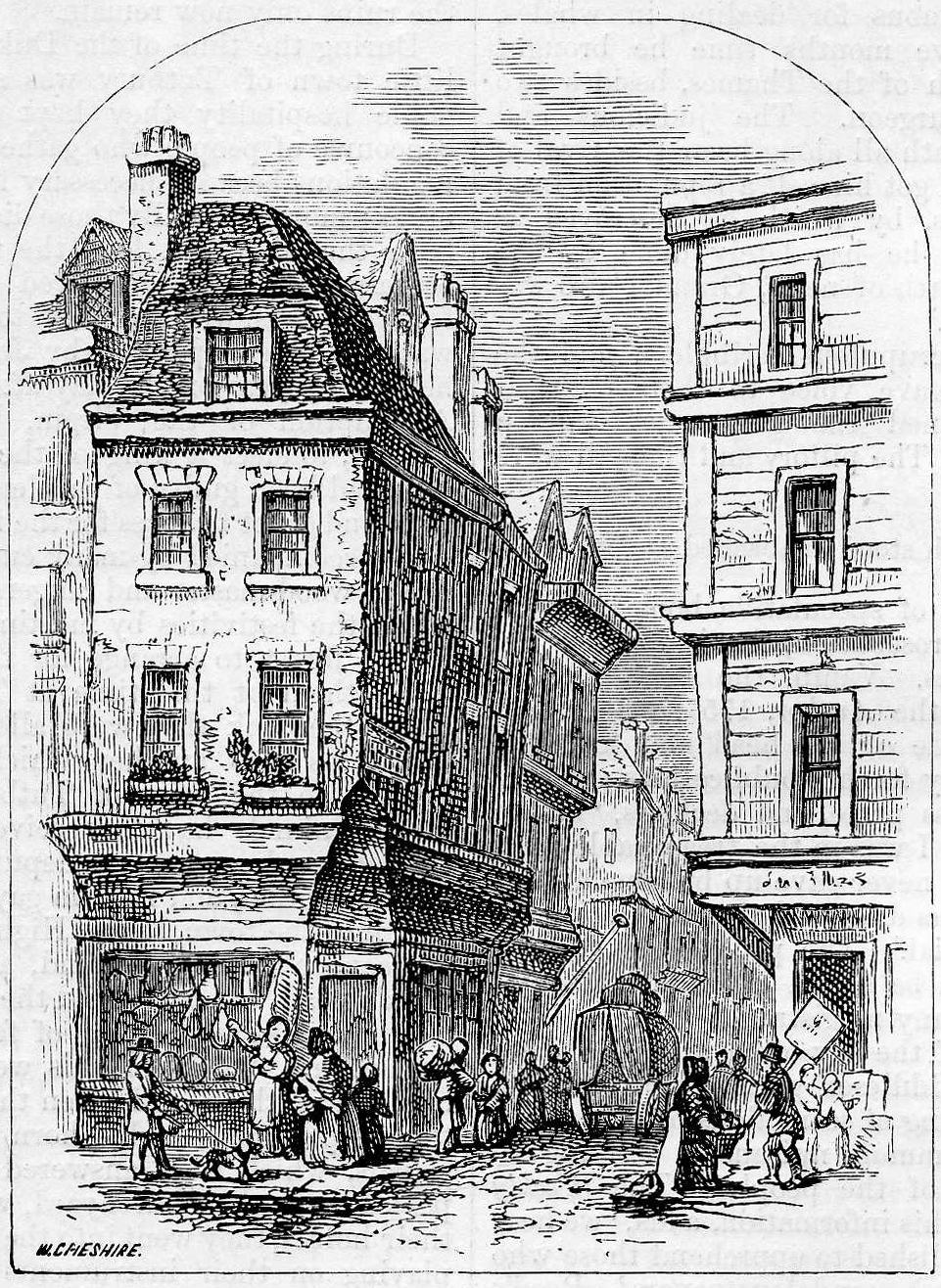

Until the early 19th century, Grub Street was a street close to

Until the early 19th century, Grub Street was a street close to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

's impoverished Moorfields district that ran from Fore Street east of St Giles-without-Cripplegate

St Giles-without-Cripplegate is an Anglican church in the City of London, located on Fore Street within the modern Barbican complex. When built it stood without (that is, outside) the city wall, near the Cripplegate. The church is dedicated to S ...

north to Chiswell Street

Chiswell Street is in Islington, London, England. Historic England have seven entries for listed buildings in Chiswell Street.

Location

The street, in St Luke's, Islington, runs east-west and forms part of the B100 road. At the west end it be ...

. It was pierced along its length with narrow entrances to alleys and courts, many of which retained the names of early signboards. Its bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

society was set amidst the impoverished neighbourhood's low-rent dosshouse

A flophouse (American English) or dosshouse (British English) is a place that offers very low-cost lodging, providing space to sleep and minimal amenities.

Characteristics

Historically, flophouses, or British "doss-houses", have been used for ...

s, brothels and coffeehouses.

Famous for its concentration of impoverished " hack writers", aspiring poets, and low-end publishers and booksellers, Grub Street existed on the margins of London's journalistic and literary scene.

According to Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

's ''Dictionary

A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged alphabetically (or by radical and stroke for ideographic languages), which may include information on definitions, usage, etymologies ...

'', the term was "originally the name of a street... much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems, whence any mean production is called grubstreet". Johnson himself had lived and worked on Grub Street early in his career. The contemporary image of Grub Street was popularised by Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

in his '' Dunciad''.

The street was later renamed Milton Street, which was partly swallowed up by the Barbican Estate

The Barbican Estate, or Barbican, is a residential complex of around 2,000 flats, maisonettes, and houses in central London, England, within the City of London. It is in an area once devastated by World War II bombings and densely populated b ...

development, but still survives in part. The street name no longer exists, but Grub Street has since become a pejorative term for impoverished hack writers and writings of low literary value.

Toponymy

Grub Street appears to have taken its name from a refuse ditch that ran alongside (grub), and variations on the name include Grobstrat (1217–1243), Grobbestrate (1277–1278), Grubbestrate (1281), Grubbestrete (1298), Grubbelane (1336), Grubstrete, and Crobbestrate. Grub is also a derogatorynoun

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, d ...

applied to 'a person of mean abilities, a literary hack; in recent use, a person of slovenly attire and unpleasant manners.'

According to the Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

the verb

A verb () is a word (part of speech) that in syntax generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual descri ...

grub means "To dig superficially; to break up the surface of (the ground); to clear (ground) of roots and stumps." The earliest use of the word is in 1300, "Theif hus brecand, or gruband grund", and in 1572 "Ze suld your ground grube with simplicitie".

History

Early history

Grub Street was in Cripplegate ward, in the parish of

Grub Street was in Cripplegate ward, in the parish of St Giles-without-Cripplegate

St Giles-without-Cripplegate is an Anglican church in the City of London, located on Fore Street within the modern Barbican complex. When built it stood without (that is, outside) the city wall, near the Cripplegate. The church is dedicated to S ...

(Cripplegate ward was bisected by the city walls, and therefore was both 'within' and 'without'). Much of the area was originally extensive marshlands from the Fleet Ditch

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers, all of which today contain foul water for treatment. Its headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath, each of which was dammed into a series of ponds—the Hampstead Ponds an ...

, to Bishopsgate, contiguous with Moorfields to the east.

The St Alphage Churchwardens' Accounts of 1267 mention a stream running from the nearby marsh, through Grub Street, and under the city walls into the Walbrook river, which may have provided the local population with drinking water, however the marshes were drained in 1527.

One of Grub Street's early residents was the notable recluse Henry Welby, the owner of the estate of Goxhill in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

. In 1592 his half-brother attempted to shoot him with a pistol. Shocked, he took a house on Grub Street and remained there, in near-total seclusion, for the rest of his life. He died in 1636 and was buried at St Giles

Saint Giles (, la, Aegidius, french: Gilles), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 6th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly lege ...

in Cripplegate. The virginalist

The virginals (or virginal) is a keyboard instrument of the harpsichord family. It was popular in Europe during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Description

A virginal is a smaller and simpler rectangular or polygonal form of ha ...

Giles Farnaby also lived in Grub Street from 1634 until his death in 1640.

An early use of the land surrounding Grub Street was

An early use of the land surrounding Grub Street was archery

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In m ...

. In ''Records of St. Giles' Cripplegate'' (1883), the author describes an order made by Henry VII to convert Finsbury Fields from gardens, to fields for archery practice, however in Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

times archery became unfashionable, and Grub Street is described as largely deserted, "except for low gambling houses and bowling-alleys—or, as we should call them, skittle-grounds." John Stow

John Stow (''also'' Stowe; 1524/25 – 5 April 1605) was an English historian and antiquarian. He wrote a series of chronicles of English history, published from 1565 onwards under such titles as ''The Summarie of Englyshe Chronicles'', ''The C ...

also referred to Grubstreete in ''A Survey of London Volume II'' (1603) as "It was convenient for bowyers, since it lay near the Archery-butts in Finsbury Fields", and in 1651 the poet Thomas Randoph wrote "Her eyes are Cupid's Grub-Street: the blind archer, Makes his love-arrows there."

''The little London directory of 1677'' lists six merchants living in 'Grubſreet', and Costermongers also plied their trade—a Mr Horton, who died in September 1773, earned a fortune of £2,000 by hiring wheelbarrows out. Land was cheap and occupied mostly by the poor, and the area was renowned for the presence of Ague

Ague may refer to:

* Fever

* Malaria

* Agué, Benin

* Duck ague, a hunting term

See also

* Kan Ague, a residential area of Patikul, Sulu

Patikul, officially the Municipality of Patikul ( Tausūg: ''Kawman sin Patikul''; tl, Bayan ng Patikul ...

and the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

; in the 1660s the Great Plague of London killed nearly eight thousand of the parish's inhabitants.

The population of St Giles in 1801 has been estimated at about 25,000 people, but by the end of the 19th century this was dropping steadily. In the 18th century Cripplegate was well known as an area haunted by insalubrious folk, and by the mid-19th century crime was rife. Methods of dealing with criminals were severe—thieves and murderers were "left dangling in their chains on Moorfields."

The use of gibbets was common, and four 'cages' were maintained by the parish, for use as a Lying-in hospital, housing the poor, and 'idle imposters'. One such cage stood amidst the poor quality housing stock of Grub Street; destitution was viewed as a crime against society, and was punishable by whipping, and also by having a hole cut in the gristle of the right ear. Well before the influx of writers in the 18th century, Grub street was therefore in an economically deprived area. John Garfield's ''Wandring Whore issue V'' (1660) lists several 'Crafty Bawds' operating from the Three Sugar-Loaves, and also mentions a Mrs Wroth as a 'common whore'.

Early literature

The earliest literary reference to Grub Street appears in 1630 by theEnglish

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

John Taylor John Taylor, Johnny Taylor or similar may refer to:

Academics

*John Taylor (Oxford), Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, 1486–1487

*John Taylor (classical scholar) (1704–1766), English classical scholar

*John Taylor (English publisher) (178 ...

. "When strait I might descry, The Quintescence of Grubstreet, well distild Through Cripplegate in a contagious Map". The local population was known for its nonconformist views; its Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

preacher Samuel Annesley

Samuel Annesley (c. 1620 – 1696) was a prominent Puritan and nonconformist pastor, best known for the sermons he collected as the series of ''Morning Exercises''.

Life

He was born in Haseley, in Warwickshire in 1620, and christened on the 26th ...

had been replaced in 1662 by an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

. Famous 16th-century Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s included John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the su ...

, who may have authored his Book of Martyrs in the area, the historian John Speed

John Speed (1551 or 1552 – 28 July 1629) was an English cartographer, chronologer and historian of Cheshire origins.S. Bendall, 'Speed, John (1551/2–1629), historian and cartographer', ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (OUP 2004/ ...

, and the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

printer and poet Robert Crowley. The Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem '' Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

also lived near Grub Street.

Press freedom

In 1403 the City of London Corporation approved the formation of a Guild ofstationer

Stationery refers to commercially manufactured writing materials, including cut paper, envelopes, writing implements, continuous form paper, and other office supplies. Stationery includes materials to be written on by hand (e.g., letter paper) ...

s. Stationers were either booksellers, illuminators, or bookbinders. Printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ea ...

gradually displaced manuscript production, and by the time that the Guild received a royal charter of incorporation on 4 May 1557, becoming the Stationers' Company

The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (until 1937 the Worshipful Company of Stationers), usually known as the Stationers' Company, is one of the livery companies of the City of London. The Stationers' Company was formed in ...

, it was in effect a Printers' Guild. In 1559, it became the 47th livery company.

The Stationers' Company had considerable powers of search and seizure, backed by the state (which supplied the force and authority to guarantee copyright). This monopoly continued until 1641 when, inflamed by the treatment of religious dissenters such as John Lilburne and William Prynne

William Prynne (1600 – 24 October 1669), an English lawyer, voluble author, polemicist and political figure, was a prominent Puritan opponent of church policy under William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury (1633–1645). His views were presbyter ...

, the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

abolished the Star Chamber

The Star Chamber (Latin: ''Camera stellata'') was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (c. 1641), and was composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the judic ...

(a court which controlled the press) with the Habeas Corpus Act 1640. This led to the de facto cessation of state censorship of the press. Although in 1641 token punishments were given to those responsible for unlicensed and hostile pamphlets published around London—including Grub Street—Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

and radical pamphlets continued to be distributed by an informal network of street hawkers, and dissenters from within the Stationers' Company.

Tabloid journalism became rife; the unstable political climate resulted in the publication from Grub Street of anti-Caroline

Caroline may refer to:

People

* Caroline (given name), a feminine given name

* J. C. Caroline (born 1933), American college and National Football League player

* Jordan Caroline (born 1996), American (men's) basketball player

Places Antarctica

* ...

literature, along with blatant lies and anti-Catholic stories regarding the Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantatio ...

; stories that were advantageous to the parliamentary leadership. Following the King's failed attempt to arrest several members of the Commons, Grub Street printer Bernard Alsop became personally involved in the publication of false pamphlets, including a fake letter from the Queen that resulted in John Bond being pilloried

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the stoc ...

. Alsop and colleague Thomas Fawcett

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

were sent to Fleet Prison for several months.

Throughout the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

therefore, publishers and writers remained answerable to the law. State control of the press was tightened in the Licensing Order of 1643, but although the new regime was arguably as restrictive as the monopoly that the Stationers' Company once enjoyed, parliament was unable to control the number of renegade presses that flourished during the Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

. The freedoms ensured by the Bill of Rights 1689 led indirectly to the refusal in 1695 of the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

to renew the Licensing of the Press Act 1662

The Licensing of the Press Act 1662 was an Act of the Parliament of England (14 Car. II. c. 33) with the long title "An Act for preventing the frequent Abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Books and Pamphlets and for regulating ...

, a law which required all printing presses to be licensed by Parliament. This lapse led to a freer press, and a rise in the volume of printed matter. Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

wrote to a friend in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, "I could send you a great deal of news from the ''Republica Grubstreetaria'', which was never in greater altitude."

Hacks

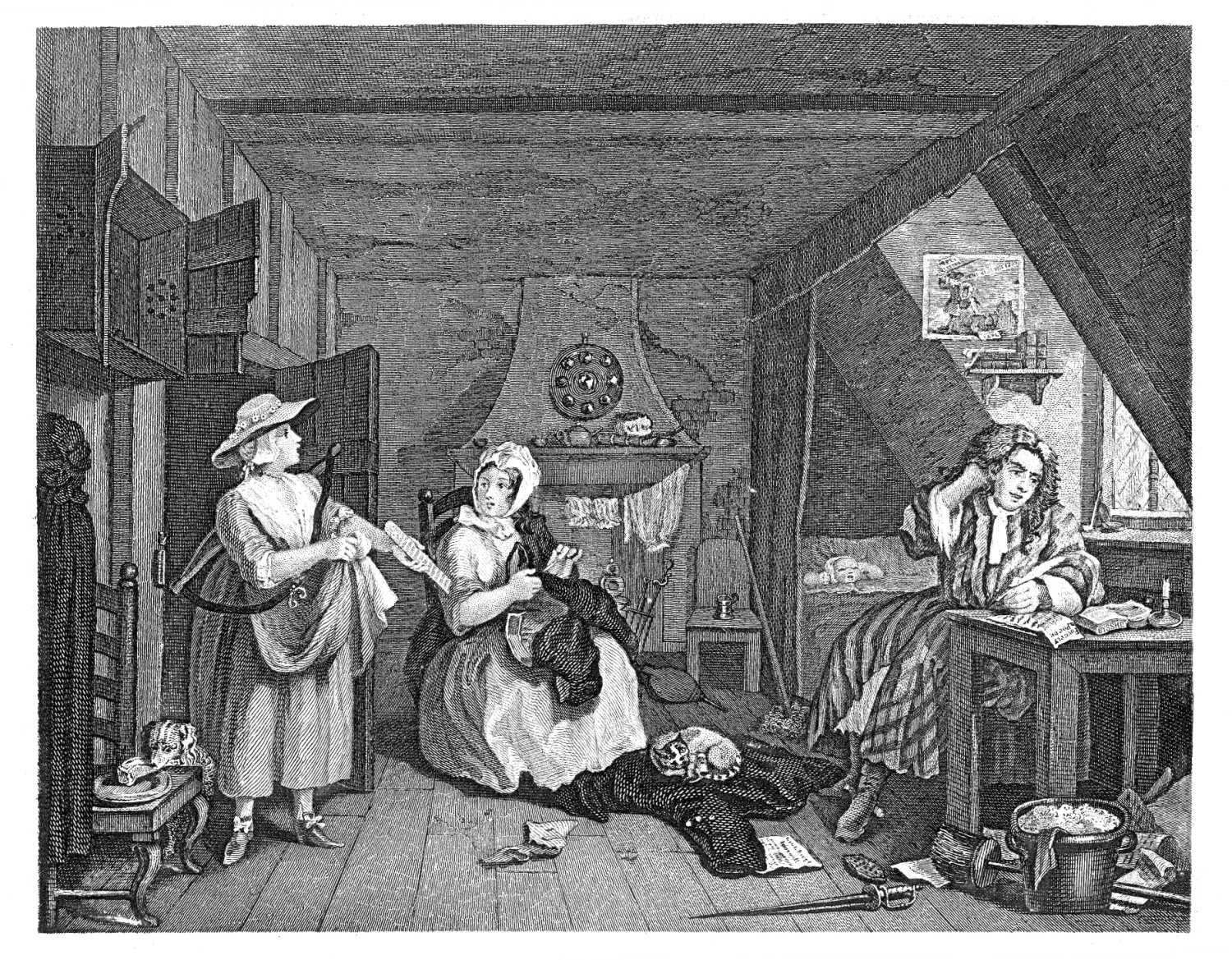

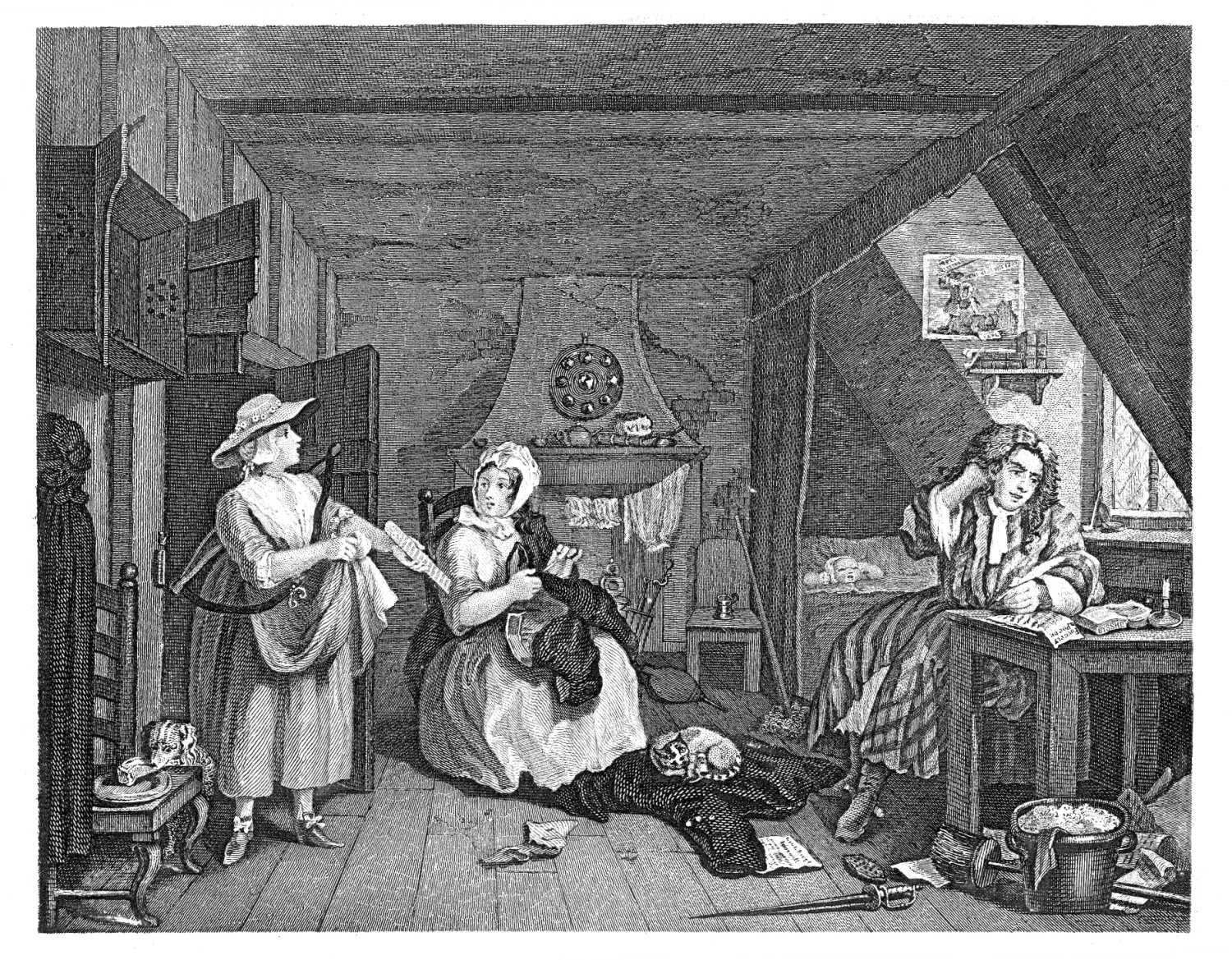

Publishing houses proliferated in Grub Street, and this, combined with the number of local garrets, meant that the area was an ideal home for hack writers. In ''The Preface'', when describing the harsh conditions a writer suffered, Tom Brown's self-parody referred to being "Block'd up in a Garret". Such contemporary views of the writer, in his inexpensive

Publishing houses proliferated in Grub Street, and this, combined with the number of local garrets, meant that the area was an ideal home for hack writers. In ''The Preface'', when describing the harsh conditions a writer suffered, Tom Brown's self-parody referred to being "Block'd up in a Garret". Such contemporary views of the writer, in his inexpensive Ivory Tower

An ivory tower is a metaphorical place—or an atmosphere—where people are happily cut off from the rest of the world in favor of their own pursuits, usually mental and esoteric ones. From the 19th century, it has been used to designate an e ...

high above the noise of the city, were immortalised by William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like s ...

in his 1736 illustration The Distrest Poet

''The Distrest Poet'' is an oil painting produced sometime around 1736 by the British artist William Hogarth. Reproduced as an etching and engraving, it was published in 1741 from a third state plate produced in 1740. The scene was probably insp ...

. The street name became a synonym for a hack writer; in a literary context, 'hack' is derived from Hackney—a person whose services may be for hire, especially a literary drudge. In this framework, hack was popularised by authors such as Andrew Marvell, Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith (10 November 1728 – 4 April 1774) was an Anglo-Irish novelist, playwright, dramatist and poet, who is best known for his novel ''The Vicar of Wakefield'' (1766), his pastoral poem ''The Deserted Village'' (1770), and his pl ...

, John Wolcot

John Wolcot (baptised 9 May 1738 – 14 January 1819) was an English satirist, who wrote under the pseudonym of "Peter Pindar".

Life

Wolcot was baptised at Dodbrooke, near Kingsbridge, Devon. In the parish register, his surname was spelled " ...

, and Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves ar ...

. Ned Ward's late 17th-century description reinforces a common view of Grub Street authors, as little more than prostitutes:

One such author was Samuel Boyse. Contemporary accounts picture him as a dishonest and disreputable rogue, paid for each individual line of prose as a Jack of all trades, master of none. He apparently lived in squalor, often drunk, and on one occasion after pawning his shirt, he fashioned a replacement out of paper. To be a called a 'Grub Street author' was therefore often viewed as an insult, however Grub Street hack James Ralph

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

defended the trade of the journalist, contrasting it with the supposed hypocrisy of more esteemed professions:

Periodicals

In response to the newly increased demand for reading matter in the Augustan period, Grub Street became a popular source of periodical literature. One publication to take advantage of the reduction of state control was ''A Perfect Diurnall'' (despite its title, a weekly publication). However it quickly found its name copied by unscrupulous Grub Street publishers, so obviously that the newspaper was forced to issue a warning to its readers. Toward the end of the 17th century authors such asJohn Dunton

John Dunton (4 May 1659 – 1733) was an English bookseller and author. In 1691 he founded The Athenian Society to publish ''The Athenian Mercury'', the first major popular periodical and first miscellaneous periodical in England. In 1693, for fo ...

worked on a range of periodicals, including ''Pegasus'' (1696), and ''The Night Walker: or, Evening Rambles in search after lewd Women'' (1696–1697). Dunton pioneered the advice column in ''Athenian Mercury'' (1690–1697). The satirical writer and publican Ned Ward published ''The London Spy'' (1698–1700) in monthly instalments, for over a year and a half. It was conceived as a guide to the sights of the city, but as a periodical also contained details on taverns, coffee-houses, tobacco shops, and bagnios.

Other publications included the Whig ''

Other publications included the Whig ''Observator

''Observator'' is the sixth studio album by The Raveonettes, and was released on 11 September 2012.

Background

Singer Sune Rose Wagner traveled to Venice, Los Angeles#Venice Beach, Venice Beach to gather inspiration for a new album. He ended up ...

'' (1702–1712), and the Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

''Rehearsal'' (1704–1709), both superseded by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

's ''Weekly Review'' (1704–1713), and Jonathan Swift's ''Examiner'' (1710–1714). English newspapers were often politically sponsored, and Grub Street was host to several such publications; between 1731 and 1741 Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader ...

's ministry was reported to have spent about £50,077 (about £ today) nationally of Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or in p ...

funds on bribes to such newspapers. Allegiances changed often, with some authors changing their political stance on receipt of bribes from secret service funds.

Such changes helped maintain the level of disdain with which the establishment viewed journalists and their trade, an attitude often reinforced by the abuse publications would print about their rivals. Titles such as ''Common Sense'', ''Daily Post'', and the ''Jacobite's Journal'' (1747–1748) were often guilty of this practice, and in May 1756 an anonymous author described journalists as "dastardly mongrel insects, scribbling incendiaries, starveling savages, human shaped tygers, senseless yelping curs..." In describing his profession, Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

, a Grub Street man himself, said "A news-writer is a man without virtue who writes lies at home for his own profit. To these compositions is required neither genius nor knowledge, neither industry nor sprightliness, but contempt of shame and indifference to truth are absolutely necessary."

Taxation

In 1711 Queen Anne gave royal assent to the 1712 Stamp Act, which imposed new taxes on newspapers. The Queen addressed the House of Commons: "Her majesty finds it necessary to observe, how great license is taken in publishing false and scandalous libels, such as are a reproach to any Government. This evil seems to be grown too strong for the laws now in force. It is therefore recommended to you to find a remedy equal to the mischief." The passage of the Act was partly an attempt to silence Whig pamphleteers and dissenters, who had been critical of the then Tory government. Every copy of a news-carrying publication printed on a half-sheet of paper became liable to a duty of a halfpenny, and if printed on a full sheet, apenny

A penny is a coin ( pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is t ...

. A duty of a shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

was placed on advertisements. Pamphlets were charged a flate rate of two shillings per sheet for each edition, and were obliged to include the name and address of the printer. The introduction of the Act caused protests from publishers and authors alike, including Daniel Defoe, and Jonathan Swift, who in support of the Whig press wrote:

Although the Act had the unfortunate side-effect of closing down several newspapers, publishers used a weakness in the legislation which meant that newspapers of six pages (a half-sheet ''and'' a whole sheet) were only charged at the flat pamphlet rate of two shillings per sheet (regardless of the number of copies printed). Many publications thus expanded to six pages, filled the extra space with extraneous matter, and raised their prices to absorb the tax. Newspapers also used the extra space to introduce serials, hoping to hook readers into buying the next instalment. The periodical nature of the Newspaper allowed writers to develop their arguments over successive weeks, and the newspaper began to overtake the pamphlet as the primary medium for political news and comment.

By the 1720s 'Grub Street' had grown from a simple street name to a term for all manner of low-level publishing. The popularity of

Although the Act had the unfortunate side-effect of closing down several newspapers, publishers used a weakness in the legislation which meant that newspapers of six pages (a half-sheet ''and'' a whole sheet) were only charged at the flat pamphlet rate of two shillings per sheet (regardless of the number of copies printed). Many publications thus expanded to six pages, filled the extra space with extraneous matter, and raised their prices to absorb the tax. Newspapers also used the extra space to introduce serials, hoping to hook readers into buying the next instalment. The periodical nature of the Newspaper allowed writers to develop their arguments over successive weeks, and the newspaper began to overtake the pamphlet as the primary medium for political news and comment.

By the 1720s 'Grub Street' had grown from a simple street name to a term for all manner of low-level publishing. The popularity of Nathaniel Mist

Nathaniel Mist (died 30 September 1737) was an 18th-century British printer and journalist whose ''Mist's Weekly Journal'' was the central, most visible, and most explicit opposition newspaper to the whig administrations of Robert Walpole. Whe ...

's ''Weekly Journal'' gave rise to a plethora of new publications, including the ''Universal Spectator'' (1728), the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

''Weekly Miscellany'' (1732), the ''Old Whig'' (1735), ''Common Sense'' (1737), and the ''Westminster Journal''. Such publications could be strident in their criticism of government ministers—''Common Sense'' in 1737 compared Walpole to the infamous outlaw Dick Turpin

Richard Turpin (bapt. 21 September 1705 – 7 April 1739) was an English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. Turpin may have followed his father's trade as a butcher ear ...

:

In response, a 1737 edition of the ''Craftsman'' proposed a tax on urine, and ten years later the ''Westminster Journal'', in a critique of proposed new taxes on food, servants, and malt, proposed a tax on human excrement.

Not all publications were based entirely on politics however. The ''Grub Street Journal

''The Grub-Street Journal'', published from 8 January 1730 to 1738, was a satire on popular journalism and hack-writing as it was conducted in Grub Street in London. It was largely edited by the nonjuror Richard Russel and the botanist John Marty ...

'' was better known in literary circles for its combative nature, and has been compared to the modern-day ''Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satire, satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely r ...

''. Despite its name, it was printed on nearby Warwick Lane. It began in 1730 as a literary journal and became known for its bellicose writings on individual authors. It is considered by some to have been a vehicle for Alexander Pope's attacks on his enemies in Grub Street, but although he contributed to early issues the full extent of his involvement is unknown. Once his interest in the publication waned ''The Journal'' began to generalise, satirising medicine, theology, theatre, justice, and other social issues. It often contained contradictory accounts of events reported by the previous week's newspapers, its writers inserting sarcastic remarks on the inaccuracies printed by their rivals. It ran until 1737 when it became the ''Literary Courier of Grub-street'', which lingered for a further six months before vanishing altogether.

Newspapers and their authors were not yet completely free from state control. In 1763

Newspapers and their authors were not yet completely free from state control. In 1763 John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fo ...

was charged with seditious libel

Sedition and seditious libel were criminal offences under English common law, and are still criminal offences in Canada. Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection a ...

for his attacks on a speech by George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, in issue 45 of ''The North Briton

''The North Briton'' was a radical newspaper published in 18th-century London. The North Briton also served as the pseudonym of the newspaper's author, used in advertisements, letters to other publications, and handbills.

Although written anon ...

''. The King felt personally insulted and general warrants were issued for the arrest of Wilkes and the newspaper's publishers. He was arrested, convicted of libel, fined, and imprisoned. During their search for Wilkes, the king's messengers had visited the home of a Grub Street printer named John Entick

John Entick (c.1703 – May 1773) was an English schoolmaster and author. He was largely a hack writer, working for Edward Dilly, and he padded his credentials with a bogus M.A. and a portrait in clerical dress; some of his works had a more la ...

. Entick had printed several copies of ''The North Briton'', but not number 45.

The messengers spent four hours searching his home, and eventually carried away more than two hundred unrelated charts and pamphlets. Wilkes had filed for damages against the Under Secretary of State

Under Secretary of State (U/S) is a title used by senior officials of the United States Department of State who rank above the Assistant Secretaries and below the Deputy Secretary.

From 1919 to 1972, the Under Secretary was the second-ranking of ...

Robert Woods and won his case, and two years later Entick pursued the chief messenger Nicholas Carrington in similar fashion—and was awarded £2,000 in compensation. Carrington appealed, but was ultimately unsuccessful; Chief Justice Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

upheld the verdict with a landmark judgement that established the limits of executive power in English law, that an officer of the state could only act lawfully in a manner prescribed by statute or common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

. The judgement also formed part of the background to the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourth Amendment (Amendment IV) to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. It prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. In addition, it sets requirements for issuing warrants: warrants must be issued by a judge o ...

.

Infighting

In 1716 the bookseller and

In 1716 the bookseller and publisher

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creation and distribution of printed works, such as books, newsp ...

Edmund Curll acquired a manuscript that belonged to Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

. Curll advertised the work as part of a forthcoming volume of poetry, and was soon contacted by Pope who warned him not to publish the poems. Curll ignored him and published Pope's work under the title ''Court Poems''. A meeting between the two was arranged, at which Pope poisoned Curll with an emetic. Several days later he also published two pamphlets describing the meeting, and proclaimed Curll's death.

Pope hoped that the combination of the poisoning and the wit of his writing would change the public view of Curll from a victim, to a deserving villain. Meanwhile, Curll responded by publishing material critical of Pope and his religion. The incident, meant to secure Pope's status as an elevated figure amongst his peers, created a lifelong and bitter rivalry between the two men, but may have been beneficial to both; Pope as the man of letters under constant attack from the hacks of Grub Street, and Curll using the incident to increase the profits from his business.

Pope later immortalised Grub Street in his 1728 poem ''The Dunciad

''The Dunciad'' is a landmark, mock-heroic, narrative poem by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times from 1728 to 1743. The poem celebrates a goddess Dulness and the progress of her chosen agents as they bring ...

'', a satire of "the Grub-street Race" of commercial writers. Such infighting was not unusual, but a particularly notable episode occurred from 1752–1753, when Henry Fielding started a "paper war" against hack writers on Grub Street. Fielding had worked in Grub Street during the late 1730s. His career as a dramatist was curtailed by the Theatrical Licensing Act (provoked by Fielding's anti-Walpole satire such as ''Tom Thumb

Tom Thumb is a character of English folklore. ''The History of Tom Thumb'' was published in 1621 and was the first fairy tale printed in English. Tom is no bigger than his father's thumb, and his adventures include being swallowed by a cow, tangl ...

'' and '' Covent Garden Tragedy'') and he turned to law, supporting his income with normal Grub Street work. He also launched ''The Champion'', and over the following years edited several newspapers, including from 1752–1754 ''The Covent-Garden Journal

''The Covent-Garden Journal'' (modernised as ''The Covent Garden Journal'') was an English literary periodical published twice a week for most of 1752. It was edited and almost entirely funded by novelist, playwright, and essayist Henry Fielding, ...

''. The "war" spanned many of London's publications, and resulted in countless essays, poems, and even a series of mock epic poems starting with Christopher Smart

Christopher Smart (11 April 1722 – 20 May 1771) was an English poet. He was a major contributor to two popular magazines, ''The Midwife'' and ''The Student'', and a friend to influential cultural icons like Samuel Johnson and Henry Fie ...

's ''The Hilliad

''The Hilliad'' was Christopher Smart's Mock-heroic, mock epic poem written as a literary attack upon John Hill (author), John Hill on 1 February 1753. The title is a play on Alexander Pope's ''The Dunciad'' with a substitution of Hill's name, wh ...

'' (a pun on Pope's ''Dunciad''). Although it is not clear what started the dispute, it resulted in a divide of authors who either supported Fielding or Hill, and few in between.

The avariciousness of the Grub Street press was often demonstrated in the manner in which they treated notable, or notorious public figures. John Church, an independent minister born in 1780, raised the ire of the local hacks when he admitted he had acted 'imprudently' following allegations he had sodomised young men in his congregation. Satire was a popular pastime—the Mary Toft

Mary Toft (née Denyer; c. 1701–1763), also spelled Tofts, was an English woman from Godalming, Surrey, who in 1726 became the subject of considerable controversy when she tricked doctors into believing that she had given birth to rabbits.

...

affair of 1726, concerning a woman who fooled some of the medical establishment into believing she had given birth to rabbits—produced a notable dirge of diaries, letters, satiric poems, ballads, false confessions, cartoons, and pamphlets.

Later history

Grub Street was renamed as Milton Street in 1830, apparently in memory of a tradesman who owned the building lease of the street. By the middle of the 19th century it had lost some of its negative connotations; authors were by that time viewed in the same light as traditionally more esteemed professions, although 'Grub Street' remained a metaphor for the commercial production of printed matter, regardless of whether such matter actually originated from Grub Street itself. Writer George Augustus Henry Sala said that during his years as a Grub Street 'hack', "most of us were about the idlest young dogs that squandered away their time on the pavements of Paris or London. We would not work. I declare in all candour that... the average number of hours per week which I devoted to literary production did not exceed four." Although the street no longer exists in name (and modern construction has changed much of the area), the name continues to exist in modern use. Much of the area was destroyed by enemy bombing in

Although the street no longer exists in name (and modern construction has changed much of the area), the name continues to exist in modern use. Much of the area was destroyed by enemy bombing in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and has since been replaced by the Barbican Estate

The Barbican Estate, or Barbican, is a residential complex of around 2,000 flats, maisonettes, and houses in central London, England, within the City of London. It is in an area once devastated by World War II bombings and densely populated b ...

. Milton Street still exists. The area was heavily damaged during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and most of Milton Street was itself swallowed up by the Barbican Estate

The Barbican Estate, or Barbican, is a residential complex of around 2,000 flats, maisonettes, and houses in central London, England, within the City of London. It is in an area once devastated by World War II bombings and densely populated b ...

development after the war. A short section survives between Silk Street and Chiswell Street, and borders the City of London's Brewery Conservation Area.

Legacy

As Grub Street became a metaphor for the commercial production of printed matter, it gradually found use in early 18th-centuryAmerica

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. Early publications such as handwritten ditties and squibs were circulated among the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

and taverns and coffee-houses. As in England, many were directed at politicians of the day.

"Grub Street Productions Grub Street Productions was an American production company founded in 1989 by three writers and producers - the late David Angell (who later was a victim of the September 11 attacks), Peter Casey and David Lee - who met while working on '' Cheers ...

," a partnership of American TV producers David Angell

David Lawrence Angell (April 10, 1946 – September 11, 2001) was an American screenwriter and television producer. He won multiple Emmy Awards as the creator and executive producer of the ''Cheers'' spin-off shows ''Wings'' and ''Frasier'' wit ...

, Peter Casey

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

and David Lee, produced the situation comedies

A sitcom, a portmanteau of situation comedy, or situational comedy, is a genre of comedy centered on a fixed set of characters who mostly carry over from episode to episode. Sitcoms can be contrasted with sketch comedy, where a troupe may use new ...

''Wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expresse ...

'' and '' Frasier''.

See also

* Grub Street in France * List of eighteenth-century British periodicals * ''New Grub Street

''New Grub Street'' is a novel by George Gissing published in 1891, which is set in the literary and journalistic circles of 1880s London. Gissing revised and shortened the novel for a French edition of 1901.

Plot

The story deals with the lite ...

''—a novel by George Gissing

George Robert Gissing (; 22 November 1857 – 28 December 1903) was an English novelist, who published 23 novels between 1880 and 1903. His best-known works have reappeared in modern editions. They include ''The Nether World'' (1889), ''New Grub ...

, set in late-19th-century London—which contrasts a pragmatic journalist with an impoverished writer and examines the tension between commerce and art in the literary world.

* The Grub Street Opera

''The Grub Street Opera'' is a play by Henry Fielding that originated as an expanded version of his play ''The Welsh Opera''. It was never put on for an audience and is Fielding's single print-only play. As in ''The Welsh Opera'', the author of t ...

* Ernest Bramah

Ernest Bramah (20 March 186827 June 1942), the pseudonym of Ernest Brammah Smith, who was an English author. He published 21 books and numerous short stories and features. His humorous works were often ranked with Jerome K. Jerome and W. W. Jac ...

—a Grub Street author

* Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett (baptised 19 March 1721 – 17 September 1771) was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for picaresque novels such as ''The Adventures of Roderick Random'' (1748), ''The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle'' (1751) a ...

* New York Magazine

''New York'' is an American biweekly magazine concerned with life, culture, politics, and style generally, and with a particular emphasis on New York City. Founded by Milton Glaser and Clay Felker in 1968 as a competitor to ''The New Yorker'', ...

, host of ''grub street.com''

References

;Notes ;Bibliography * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * Eisenstein, Elizabeth. ''Grub Street Abroad: Aspects of the French Cosmopolitan Press from the Age of Louis XIV to the French Revolution'' (1992) *McDowell, Paula. ''The Women of Grub Street: Press, Politics and Gender in the London Literary Marketplace, 1678-1730'' (1998) * * * {{Coord, 51, 31, 13, N, 0, 05, 27, W, type:landmark_region:GB, display=title History of literature English phrases Streets in the City of London