Great Sioux War Of 1876 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of

By the early 19th century, the Northern Cheyenne became the first to wage tribal-level warfare. Because European Americans used many different names for the Cheyenne, the military may not have realized their unity. The US Army destroyed seven Cheyenne camps before 1876 and three more that year, more than any other tribes suffered in this period. From 1860 on, the Cheyenne were a major force in warfare on the Plains. "No other group on the plains achieved such centralized tribal organization and authority." The

By the early 19th century, the Northern Cheyenne became the first to wage tribal-level warfare. Because European Americans used many different names for the Cheyenne, the military may not have realized their unity. The US Army destroyed seven Cheyenne camps before 1876 and three more that year, more than any other tribes suffered in this period. From 1860 on, the Cheyenne were a major force in warfare on the Plains. "No other group on the plains achieved such centralized tribal organization and authority." The  In May 1875, Sioux delegations headed by

In May 1875, Sioux delegations headed by

The number of Indian combatants in the war is disputed with estimates ranging from 900 up to 4,000 warriors. The seven bands of the Lakota Sioux in the 1870s numbered perhaps 15,000 men, women, and children, but most of them were living on the Great Sioux Reservation and were noncombatants. An Indian agent in November 1875 said the Indians living in the unceded areas numbered "a few hundred warriors." General Crook estimated that he might face up to 2,000 warriors. Most of the Sioux who remained in the unceded territory where the war would take place were

The number of Indian combatants in the war is disputed with estimates ranging from 900 up to 4,000 warriors. The seven bands of the Lakota Sioux in the 1870s numbered perhaps 15,000 men, women, and children, but most of them were living on the Great Sioux Reservation and were noncombatants. An Indian agent in November 1875 said the Indians living in the unceded areas numbered "a few hundred warriors." General Crook estimated that he might face up to 2,000 warriors. Most of the Sioux who remained in the unceded territory where the war would take place were

In the late spring of 1876 a second, much larger campaign was launched. From Fort Abraham Lincoln marched the Dakota Column, commanded by General

In the late spring of 1876 a second, much larger campaign was launched. From Fort Abraham Lincoln marched the Dakota Column, commanded by General

Lt. Col.

Lt. Col.

While military leaders began planning a spring campaign against the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne who had refused to come in, a number of diplomatic efforts were underway in an effort to end the war.

While military leaders began planning a spring campaign against the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne who had refused to come in, a number of diplomatic efforts were underway in an effort to end the war.

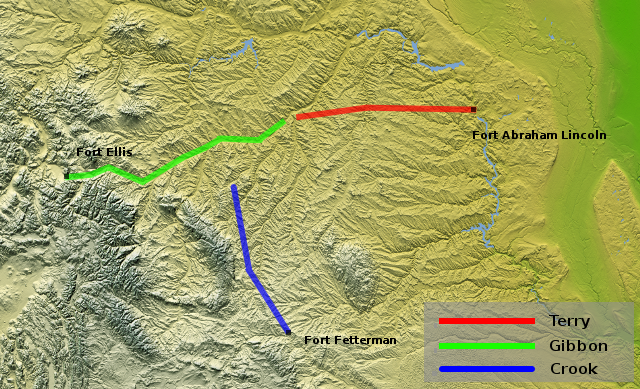

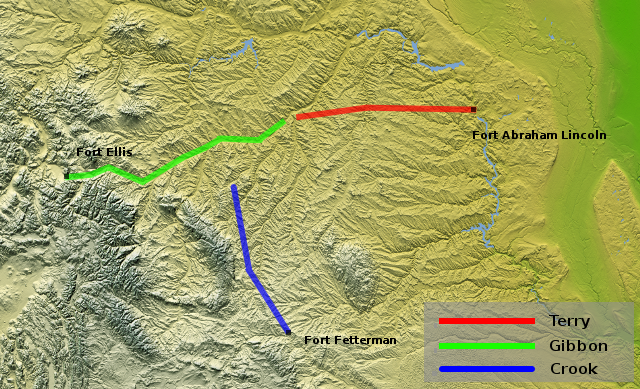

Map: Prelude to the Great Sioux War of 1876

{{DEFAULTSORT:Great Sioux War Of 1876-77 Black Hills Cheyenne tribe Conflicts in 1876 Conflicts in 1877 1876 in Dakota Territory Indian wars of the American Old West Wars involving the indigenous peoples of North America Lakota Montana Territory Native American history of Montana Native American history of Nebraska Native American history of Oklahoma Native American history of South Dakota Native American history of Wyoming Sioux Wars Wars between the United States and Native Americans Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant 1877 in Dakota Territory

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

Sioux and Northern Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

against the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. The cause of the war was the desire of the US government to obtain ownership of the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

. Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

had been discovered in the Black Hills, settlers began to encroach onto Native American lands, and the Sioux and the Cheyenne refused to cede ownership. Traditionally, American military and historians place the Lakota at the center of the story, especially because of their numbers, but some Native Americans believe the Cheyenne were the primary target of the American campaign.

Among the many battles and skirmishes of the war was the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

; often known as Custer's Last Stand, it is the most storied of the many encounters between the US Army and mounted Plains Indians. Despite the Indian victory, the Americans leveraged national resources to force the Indians to surrender, primarily by attacking and destroying their encampments and property. The Great Sioux War took place under US Presidents Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

and Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

. The Agreement of 1877 (, enacted February 28, 1877) officially annexed Sioux land and permanently established Indian reservations.

Background

The Cheyenne had migrated west to theBlack Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

and Powder River Country

The Powder River Country is the Powder River Basin area of the Great Plains in northeastern Wyoming, United States. The area is loosely defined as that between the Bighorn Mountains and the Black Hills, in the upper drainage areas of the Powder, ...

before the Lakota and introduced them to horse culture about 1730. By the late 18th century, the growing Lakota tribe had begun expanding its territory west of the Missouri River. They pushed out the Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

and formed alliances with the Cheyenne and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

to gain control of the rich buffalo hunting grounds of the northern Great Plains. The Black Hills, located in present-day western South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

, became an important source to the Lakota for lodge poles, plant resources and small game. They are considered sacred to the Lakota culture.

By the early 19th century, the Northern Cheyenne became the first to wage tribal-level warfare. Because European Americans used many different names for the Cheyenne, the military may not have realized their unity. The US Army destroyed seven Cheyenne camps before 1876 and three more that year, more than any other tribes suffered in this period. From 1860 on, the Cheyenne were a major force in warfare on the Plains. "No other group on the plains achieved such centralized tribal organization and authority." The

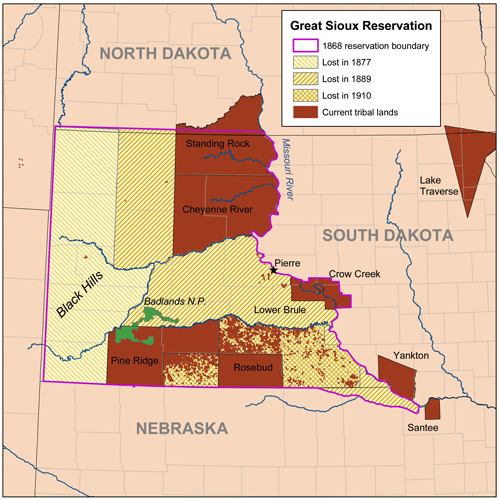

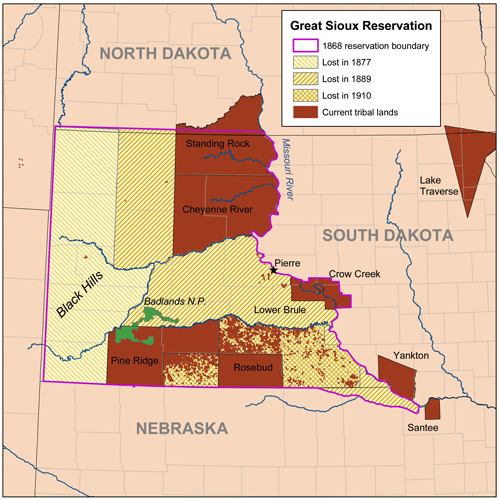

By the early 19th century, the Northern Cheyenne became the first to wage tribal-level warfare. Because European Americans used many different names for the Cheyenne, the military may not have realized their unity. The US Army destroyed seven Cheyenne camps before 1876 and three more that year, more than any other tribes suffered in this period. From 1860 on, the Cheyenne were a major force in warfare on the Plains. "No other group on the plains achieved such centralized tribal organization and authority." The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868

The Treaty of Fort Laramie (also the Sioux Treaty of 1868) is an agreement between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota and Arapaho Nation, following the failure of the first Fo ...

, signed with the US by Lakota and Northern Cheyenne leaders following Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War or the Powder River War) was an armed conflict between an alliance of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho peoples against the United States that took place in the Wyoming and Mo ...

, set aside a portion of the Lakota territory as the Great Sioux Reservation

The Great Sioux Reservation initially set aside land west of the Missouri River in South Dakota and Nebraska for the use of the Lakota Sioux, who had dominated this territory. The reservation was established in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 ...

. This comprised the western one-half of South Dakota, including the Black Hills region for their exclusive use. It also provided for a large "unceded territory" in Wyoming and Montana, the Powder River Country

The Powder River Country is the Powder River Basin area of the Great Plains in northeastern Wyoming, United States. The area is loosely defined as that between the Bighorn Mountains and the Black Hills, in the upper drainage areas of the Powder, ...

, as Cheyenne and Lakota hunting grounds. On both the reservation and the unceded territory, white men were forbidden to trespass, except for officials of the U.S. government.

The growing number of miners and settlers encroaching in the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of N ...

, however, rapidly nullified the protections. The US government could not keep settlers out. By 1872, territorial officials were considering harvesting the rich timber resources of the Black Hills, to be floated down the Cheyenne River

The Cheyenne River ( lkt, Wakpá Wašté; "Good River"), also written ''Chyone'', referring to the Cheyenne people who once lived there, is a tributary of the Missouri River in the U.S. states of Wyoming and South Dakota. It is approximately 2 ...

to the Missouri, where new plains settlements needed lumber. The geographic uplift area suggested the potential for mineral resources. When a commission approached the Red Cloud Agency

The Red Cloud Agency was an Indian agency for the Oglala Lakota as well as the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, from 1871 to 1878. It was located at three different sites in Wyoming Territory and Nebraska before being moved to South Dakota. It w ...

about the possibility of the Lakota's signing away the Black Hills, Colonel John E. Smith noted that this was "the only portion f their reservationworth anything to them". He concluded that "nothing short of their annihilation will get it from them".

As a result, Cheyenne and Lakota began moving west into land belonging to smaller tribes. Most battles in the coming war would be fought "on lands those Indians had taken from other tribes since 1851". The resulting effect was resistance to the Lakotas from the local Crow tribe, which had treaty on the area. Already in 1873, Crow chief Blackfoot had called for U.S. military actions against the Indian intruders. The steady Lakota invasion into treaty areas belonging to the smaller tribes guaranteed that the United States would find allies in the Arikaras and the Crows

The Common Remotely Operated Weapon Station (CROWS) is a series of remote weapon stations used by the US military on its armored vehicles and ships. It allows weapon operators to engage targets without leaving the protection of their vehicle. ...

who saw the Cheyenne and Lakotas as trespassers.]

In 1874, the government dispatched the Black Hills Expedition, Custer Expedition to examine the Black Hills. The Lakota were alarmed at his expedition. Before Custer's column had returned to Fort Abraham Lincoln

Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park is a North Dakota state park located south of Mandan, North Dakota, United States. The park is home to the replica Mandan On-A-Slant Indian Village and reconstructed military buildings including the Custer House. ...

, news of their discovery of gold was telegraphed nationally. The presence of valuable mineral resources was confirmed the following year by the Newton–Jenney Geological Expedition. Prospectors, motivated by the economic panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, began to trickle into the Black Hills in violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty. This trickle turned into a flood as thousands of miners invaded the Hills before the gold rush was over. Organized groups came from states as far away as New York, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

.

Initially, the United States Army struggled to keep miners out of the region. In December 1874, for example, a group of miners led by John Gordon from Sioux City, Iowa

Sioux City () is a city in Woodbury and Plymouth counties in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Iowa. The population was 85,797 in the 2020 census, making it the fourth-largest city in Iowa. The bulk of the city is in Woodbury County ...

, managed to evade Army patrols and reached the Black Hills, where they spent three months before the Army ejected them. Such evictions, however, increased political pressure on the Grant Administration

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The Ku ...

to secure the Black Hills from the Lakota.

In May 1875, Sioux delegations headed by

In May 1875, Sioux delegations headed by Spotted Tail

Spotted Tail (Siŋté Glešká pronounced ''gleh-shka''; birth name T'at'aŋka Napsíca "Jumping Buffalo"Ingham (2013) uses 'c' to represent 'č'. ); born c. 1823 – died August 5, 1881) was a Brulé Lakota tribal chief. Although a great warr ...

, Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

, and Lone Horn

Lone Horn (Lakota: Hewáŋžiča, or in historical spelling "Heh-won-ge-chat" or "Ha-wón-je-tah"), also called One Horn (1790 –1877), born in present-day South Dakota, was chief of the Wakpokinyan (Flies Along the Stream) band of the Minne ...

traveled to Washington, D.C. in an eleventh-hour attempt to persuade President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

to honor existing treaties and stem the flow of miners into their territories. They met with Grant, Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry ...

Columbus Delano

Columbus Delano (June 4, 1809 – October 23, 1896) was a lawyer, rancher, banker, statesman, and a member of the prominent Delano family. Forced to live on his own at an early age, Delano struggled to become a self-made man. Delano was electe ...

, and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Edward Smith Ed, Eddie, Edgar, Edward, Edwin, and similar, surnamed Smith, may refer to:

Military

* Edward H. Smith (sailor) (1889–1961), United States Coast Guard admiral, oceanographer and Arctic explorer

* Edward Smith (VC) (1898–1940), English recipien ...

. The US leaders said that the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

wanted to pay the tribes $25,000 for the land and have them relocate to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

(in present-day Oklahoma). The delegates refused to sign a new treaty with these stipulations. Spotted Tail said, "You speak of another country, but it is not my country; it does not concern me, and I want nothing to do with it. I was not born there ... If it is such a good country, you ought to send the white men now in our country there and let us alone." Although the chiefs were unsuccessful in finding a peaceful solution, they did not join Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull in the warfare that followed.

Later that year, a US commission was sent to each of the Indian agencies to hold councils with the Lakota. They hoped to gain the people's approval and thereby bring pressure on the Lakota leaders to sign a new treaty. The government's attempt to secure the Black Hills failed. While the Black Hills were at the center of the growing crisis, Lakota resentment was growing over expanding US interests in other portions of Lakota territory. For instance, the government proposed that the route of the Northern Pacific Railroad

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, whi ...

would cross through the last of the great buffalo hunting grounds. In addition, the US Army had carried out several devastating attacks on Cheyenne camps before 1876.

Combatants

The number of Indian combatants in the war is disputed with estimates ranging from 900 up to 4,000 warriors. The seven bands of the Lakota Sioux in the 1870s numbered perhaps 15,000 men, women, and children, but most of them were living on the Great Sioux Reservation and were noncombatants. An Indian agent in November 1875 said the Indians living in the unceded areas numbered "a few hundred warriors." General Crook estimated that he might face up to 2,000 warriors. Most of the Sioux who remained in the unceded territory where the war would take place were

The number of Indian combatants in the war is disputed with estimates ranging from 900 up to 4,000 warriors. The seven bands of the Lakota Sioux in the 1870s numbered perhaps 15,000 men, women, and children, but most of them were living on the Great Sioux Reservation and were noncombatants. An Indian agent in November 1875 said the Indians living in the unceded areas numbered "a few hundred warriors." General Crook estimated that he might face up to 2,000 warriors. Most of the Sioux who remained in the unceded territory where the war would take place were Oglala

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

and Hunkpapa

The Hunkpapa (Lakota: ) are a Native American group, one of the seven council fires of the Lakota tribe. The name ' is a Lakota word, meaning "Head of the Circle" (at one time, the tribe's name was represented in European-American records as ...

, numbering about 5,500 in total. Added to this were about 1,500 Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho for a total hostile Indian population of about 7,000, which might include as many as 2,000 warriors. The number of warriors participating in the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

is estimated at between 900 and 2,000.

The Indians had advantages in mobility and knowledge of the country, but all Indians were part-time warriors. In spring, they were partially immobilized by the weakness of their horses which had survived the long winter on limited forage. Much of summer and fall they spent hunting buffalo to feed their families. About one half of the Indian warriors were armed with guns, ranging from repeating rifles to antiquated muskets, and one half with bows and arrows

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles ( arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was com ...

. The short, stout Indian bow was designed to be used from horseback and was deadly at short range, but nearly worthless against a distant or well-fortified enemy. Ammunition was in short supply. Indian warriors had traditionally fought for individual prestige, rather than strategic objectives, although Crazy Horse seems to have instilled in the Sioux some sense of collective endeavor. The Cheyenne were the most centralized and best organized of the Plains Indians. The Sioux and Cheyenne were also at war with their long-time enemies, the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

and Shoshone, which drained off many of their resources.

To combat the Sioux the U.S. army had a string of forts ringing the Great Sioux Reservation and unceded territory. The largest force arrayed against the Indians at one time was in summer 1876 and consisted of 2,500 soldiers deployed in the unceded territory and accompanied by hundreds of Indian scouts and civilians. Many of the soldiers were recent immigrants and inexperienced on the frontier and in Indian warfare. Cavalry soldiers were armed with .45 caliber, single-action revolvers and the Springfield model 1873, a single-shot, breech-loading rifle which gave the soldiers a large advantage in range over most Indian firearms.

Launching the war

Grant and his administration began to consider alternatives to the failed diplomatic venture. In early November 1875, Lieutenant GeneralPhilip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

, commander of the Division of the Missouri, and Brigadier General George Crook, commander of the Department of the Platte

The Department of the Platte was a military administrative district established by the U.S. Army on March 5, 1866, with boundaries encompassing Iowa, Nebraska, Dakota Territory, Utah Territory and a small portion of Idaho. With headquarters in Om ...

, were called to Washington, D.C. to meet with Grant and several members of his cabinet to discuss the Black Hills issue. They agreed that the Army should stop evicting trespassers from the reservation, thus opening the way for the Black Hills Gold Rush

The Black Hills Gold Rush took place in Dakota Territory in the United States. It began in 1874 following the Custer Expedition and reached a peak in 1876–77.

Rumors and poorly documented reports of gold in the Black Hills go back to the early ...

. In addition, they discussed initiating military action against the bands of Lakota and Northern Cheyenne who had refused to come to the Indian agencies for council. Indian Inspector Erwin C. Watkins supported this option. "The true policy in my judgement," he wrote, "is to send troops against them in the winter, the sooner the better, and whip them into subjection."

Concerned about launching a war against the Lakota without provocation, the government instructed Indian agents in the region to notify all Lakota and Sioux to return to the reservation by January 31, 1876, or face potential military action. The US agent at Standing Rock Agency expressed concern that this was insufficient time for the Lakota to respond, as deep winter restricted travel. His request to extend the deadline was denied. General Sheridan considered the notification exercise a waste of time. "The matter of notifying the Indians to come in is perhaps well to put on paper," he commented, "but it will in all probability be regarded as a good joke by the Indians."

Meanwhile, in the council lodges of the non-treaty bands, Lakota leaders seriously discussed the notification for return. Short Bull, a member of the Soreback Band of the Oglala

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

, later recalled that many of the bands had gathered on the Tongue River. "About one hundred men went out from the agency to coax the hostiles to come in under pretense that the trouble about the Black Hills was to be settled," he said. "...All the hostiles agreed that since it was late n the seasonand they had to shoot for ''tipis'' .e., hunt buffalothey would come in to the agency the following spring."

As the deadline of January 31 passed, the new Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Q. Smith, wrote that "without the receipt of any news of Sitting Bull's submission, I see no reason why, in the discretion of the Hon. the Secretary of War, military operations against him should not commence at once." His superior, Secretary of the Interior Zachariah Chandler

Zachariah Chandler (December 10, 1813 – November 1, 1879) was an American businessman, politician, one of the founders of the Republican Party, whose radical wing he dominated as a lifelong abolitionist. He was mayor of Detroit, a four-term sena ...

agreed, adding that "the said Indians are hereby turned over to the War Department for such action on the part of the Army as you may deem proper under the circumstances." On February 8, 1876, General Sheridan telegraphed Generals Crook and Terry, ordering them to commence their winter campaigns against the "hostiles", thus starting The Great Sioux War of 1876–77.

Reynolds' campaign

While General Terry stalled, General Crook immediately launched the first strike. He dispatched ColonelJoseph J. Reynolds

Joseph Jones Reynolds (January 4, 1822 – February 25, 1899) was an American engineer, educator, and military officer who fought in the American Civil War and the postbellum Indian Wars.

Early life and career

Reynolds was born in Fleming ...

with six companies of cavalry, who located a village of about 65 lodges and attacked on the morning of March 17, 1876. Crook accompanied the column but did not play any command role. His troops initially took control of and burned the village, but they quickly retreated under enemy fire. The US troops left several soldiers on the battlefield, an action which led to Colonel Reynolds' court-martial. The US captured the band's pony herd, but the following day, the Lakota recovered many of their horses in a raid. At the time, the Army believed they had attacked Crazy Horse; however, it had actually been a village of Northern Cheyenne

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation ( chy, Tsėhéstáno; formerly named the Tongue River) is the federally recognized Northern Cheyenne tribe. Located in southeastern Montana, the reservation is approximately ...

(led by Old Bear, Two Moons

Two Moons (1847–1917), or ''Ishaynishus'' (Cheyenne: ''Éše'he Ôhnéšesêstse''), was one of the Cheyenne chiefs who took part in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and other battles against the United States Army.

Life

Two Moons was the son o ...

and White Bull) with a few Oglala (led by He Dog

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

.)

Summer expeditions

In the late spring of 1876 a second, much larger campaign was launched. From Fort Abraham Lincoln marched the Dakota Column, commanded by General

In the late spring of 1876 a second, much larger campaign was launched. From Fort Abraham Lincoln marched the Dakota Column, commanded by General Alfred Terry

Alfred Howe Terry (November 10, 1827 – December 16, 1890) was a Union general in the American Civil War and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869, and again from 1872 to 1886. In 1865, Terry led Union troops to v ...

, with 15 companies or about 570 men, including Custer and all 12 companies of the Seventh Cavalry. The Montana Column, commanded by Colonel John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the four ...

, departed Fort Ellis

Fort Ellis was a United States Army fort established August 27, 1867, east of present-day Bozeman, Montana. Troops from the fort participated in many major campaigns of the Indian Wars. The fort was closed on August 2, 1886.

History

The fort wa ...

. General Crook commanded a third column that departed Fort Fetterman to head north. The plan was for all three columns to converge simultaneously on the Lakota hunting grounds and pin down the Indians between the approaching troops.

Battle of the Rosebud

General Crook's column was the first to make contact with the northern bands in theBattle of the Rosebud

The Battle of the Rosebud (also known as the Battle of Rosebud Creek) took place on June 17, 1876, in the Montana Territory between the United States Army and its Crow and Shoshoni allies against a force consisting mostly of Lakota Sioux and Nor ...

on June 17. While Crook claimed a victory, most historians note that the Indians had effectively checked his advance. Thus the Battle of the Rosebud was at the very least a tactical draw if not a victory for the Indians. Afterward General Crook remained in camp for several weeks awaiting reinforcements, essentially taking his column out of the fighting for a significant period of time.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

and the Seventh Cavalry were ordered out from the main Dakota Column to scout the Rosebud and Big Horn river valleys. On June 25, 1876, they encountered a large village on the west bank of the Little Bighorn. The US troops were seriously beaten in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and nearly 270 men were killed, including Custer. Custer split his forces just prior to the battle and his immediate command of five cavalry companies was annihilated without any survivors. Two days later, a combined force consisting of Colonel Gibbon's column, along with Terry's headquarters staff and the Dakota Column infantry, reached the area and rescued the US survivors of the Reno-Benteen fight. Gibbon then headed his forces to the east, chasing trails but unable to engage the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors in battle.

Battle of Slim Buttes

Reinforced with the Fifth Cavalry, General Crook took to the field. Hooking up briefly with General Terry, he soon moved out on his own but did not find a large village. Running short on supplies, his column turned south and made what became called theHorsemeat March The Horsemeat March of 1876, also known as the Mud March and the Starvation March, was a military expedition led by General George Crook in pursuit of a band of Sioux fleeing from anticipated retaliation for their overwhelming victory over George ...

toward mining settlements to find food. On September 9, 1876, an advance company from his column en route to Deadwood to procure supplies stumbled across a small village at Slim Buttes, which they attacked and looted. Crazy Horse learned of the assault on the village and the next day led a counter-attack, which was repulsed. After reaching Camp Robinson, Crook's forces disbanded.

Crackdown at the agencies

In the wake of Custer's defeat at the Little Bighorn, the Army altered its tactics. They increased troop levels at the Indian agencies. That fall, they attached most of the troops to the Army for operations. They seized horses and weapons belonging to friendly bands at the agencies, for fear they would be given to the resisting northern bands. In October 1876, Army troops surrounded the villages ofRed Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

and Red Leaf. They arrested and briefly confined the leaders, holding them responsible for failing to turn in individuals arriving in camp from hostile bands. The US sent another commission to the agencies. According to historian Colin Calloway, "Congress passed a law extinguishing all Lakota rights outside the Great Sioux Reservation."

Mackenzie's campaign

Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie and his Fourth Cavalry were transferred to the Department of the Platte following the defeat at the Little Bighorn. Stationed initially at Camp Robinson, they formed the core of the Powder River Expedition that departed in October 1876 to locate the northern villages. On November 25, 1876, his column discovered and defeated a village of Northern Cheyenne in theDull Knife Fight

The Dull Knife Fight, or the Battle on the Red Fork, part of the Great Sioux War of 1876, was a battle that was fought on November 25, 1876, in present-day Johnson County, Wyoming between soldiers and scouts of the United States Army and warrior ...

in Wyoming Territory

The Territory of Wyoming was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 25, 1868, until July 10, 1890, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Wyoming. Cheyenne was the territorial capital. The bou ...

. With their lodges and supplies destroyed and their horses confiscated, the Northern Cheyenne soon surrendered. They hoped to be allowed to remain with the Sioux in the north. They were pressured to relocate to the reservation of the Southern Cheyenne

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

History

The Cheyennes and Arapahos are two distinct tribes with distinct histories. The Cheyenne (Ts ...

in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

. After a difficult council, they agreed to go.

When they arrived at the reservation in present-day Oklahoma, conditions were very difficult: inadequate rations, no buffalo left alive near the reservation, and malaria. A portion of the Northern Cheyenne, led by Little Wolf and Dull Knife

Morning Star (Cheyenne: ''Vóóhéhéve''; also known by his Lakota Sioux name ''Tȟamílapȟéšni'' or its translation, Dull Knife) (1810–1883) was a great chief of the Northern Cheyenne people and headchief of the ''Notameohmésêhese'' ("N ...

, attempted to return to the north in the fall of 1877 in the Northern Cheyenne Exodus

The Northern Cheyenne Exodus, also known as Dull Knife's Raid, the Cheyenne War, or the Cheyenne Campaign, was the attempt of the Northern Cheyenne to return to the north, after being placed on the Southern Cheyenne reservation in the Indian Terr ...

. They succeeded in reaching the north. After they divided into two bands, that led by Dull Knife was captured and imprisoned in an unheated barracks at Fort Robinson

Fort Robinson is a former U.S. Army fort and now a major feature of Fort Robinson State Park, a public recreation and historic preservation area located west of Crawford on U.S. Route 20 in the Pine Ridge region of northwest Nebraska.

The fo ...

without food or water. When the Cheyenne escaped on January 9, 1878, many died at US Army hands in the subsequent Fort Robinson massacre

The Fort Robinson breakout or Fort Robinson massacre was the attempted escape of Cheyenne captives from the U.S. army during the winter of 1878-1879 at Fort Robinson in northwestern Nebraska. In 1877, the Cheyenne had been forced to relocate fr ...

. Eventually the US government granted the Northern Cheyenne a northern reservation, the Northern Cheyenne Reservation

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation ( chy, Tsėhéstáno; formerly named the Tongue River) is the federally recognized Northern Cheyenne tribe. Located in southeastern Montana, the reservation is approximately ...

in present-day southern Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

.

Miles' campaigns

Another strategy of the US Army was to place troops deep within the heartland of Lakota Territory. In the fall of 1876, ColonelNelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

and his Fifth Infantry established Cantonment on Tongue River (later renamed Fort Keogh

Fort Keogh is a former United States Army post located at the western edge of modern Miles City, in the U.S. state of Montana. It is situated on the south bank of the Yellowstone River, at the mouth of the Tongue River.

Colonel Nelson A. Miles, ...

) from which he operated throughout the winter of 1876–77 against any hostiles he could find. In January 1877, he fought Crazy Horse and many other bands at the Battle of Wolf Mountain

The Battle of Wolf Mountain (also known as the Battle of the Wolf Mountains, Miles's Battle on the Tongue River, the Battle of the Butte, Where Big Crow Walked Back and Forth, and called the Battle of Belly Butte by the Northern Cheyenne) was a ...

. In the months that followed, his troops fought the Lakota at Clear Creek, Spring Creek and Ash Creek. Miles' continuous campaigning pushed a number of the Northern Cheyenne and Lakota to either surrender or slip across the border into Canada. Miles later commanded the US Army during the Spanish–American War.

Annexation

The Agreement of 1877 (, enacted February 28, 1877) officially took away Sioux land and permanently established Indian reservations.Diplomatic efforts

While military leaders began planning a spring campaign against the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne who had refused to come in, a number of diplomatic efforts were underway in an effort to end the war.

While military leaders began planning a spring campaign against the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne who had refused to come in, a number of diplomatic efforts were underway in an effort to end the war.

"Sell or Starve"

After the defeat at theBattle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

in June 1876, Congress responded by attaching what the Sioux call the "sell or starve" rider () to the Indian Appropriations Act of 1876 (enacted August 15, 1876) which cut off all rations for the Sioux until they terminated hostilities and ceded the Black Hills to the United States.

George Sword mission

As the winter wore on, rumors reached Camp Robinson that the northern bands were interested in surrendering. The commanding officer sent out a peace delegation. About 30 young men, mostlyOglala

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

and Northern Cheyenne

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation ( chy, Tsėhéstáno; formerly named the Tongue River) is the federally recognized Northern Cheyenne tribe. Located in southeastern Montana, the reservation is approximately ...

, departed from the Red Cloud Agency

The Red Cloud Agency was an Indian agency for the Oglala Lakota as well as the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, from 1871 to 1878. It was located at three different sites in Wyoming Territory and Nebraska before being moved to South Dakota. It w ...

on January 16, 1877, to make the dangerous journey north. Among the most prominent members of this delegation was a young Oglala named Enemy Bait (better known later as George Sword). He was the son of the prominent headman Brave Bear. The delegation found Crazy Horse on the Powder River, but found no indication that he was prepared to surrender. Other Oglala camps nearby, however, were more willing to hear the message and seriously consider surrendering at the agencies. In late February, part of the delegation continued on to find the Northern Cheyenne, where they delivered the same message.

Spotted Tail mission

The influentialBrulé

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands (sometimes called "sub-tribes") of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte (in Lakȟóta) —Sicangu Oyate—, ''Sicangu Lakota, o''r "Burnt ...

headman Spotted Tail

Spotted Tail (Siŋté Glešká pronounced ''gleh-shka''; birth name T'at'aŋka Napsíca "Jumping Buffalo"Ingham (2013) uses 'c' to represent 'č'. ); born c. 1823 – died August 5, 1881) was a Brulé Lakota tribal chief. Although a great warr ...

also agreed to lead a peace delegation out to meet with the "hostiles". Departing his agency on February 12, 1877, with perhaps 200 people, Spotted Tail moved north along the eastern edge of the Black Hills. They soon found a large village of Miniconjou

The Miniconjou (Lakota: Mnikowoju, Hokwoju – ‘Plants by the Water’) are a Native American people constituting a subdivision of the Lakota people, who formerly inhabited an area in western present-day South Dakota from the Black Hills i ...

under Touch the Clouds

Touch the Clouds ( Lakota: Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagya or Maȟpíya Íyapat'o) (c. 1838 – September 5, 1905) was a chief of the '' Minneconjou'' Teton Lakota (also known as Sioux) known for his bravery and skill in battle, physical strength and ...

, near Short Pine Hills on the Little Missouri River. After several days of councils, they agreed to go in and surrender at the Spotted Tail Agency.

Spotted Tail's delegation continued on to the Little Powder River, where they met with Miniconjou, Sans Arc, Oglala and a few Northern Cheyenne, including leaders such as Black Shield, Fast Bull, Lame Deer

Lame Deer (1821-1877), also called "The Elk that Whistles Running," was a first chief of the Miniconjou Lakota (trans. "They who plant by the water") and vice chief of the Wakpokinyan (trans. "To Fly along the river") band.

Biography

Lame Deer ...

, and Roman Nose

Roman Nose ( – September 17, 1868), also known as Hook Nose ( chy, Vóhko'xénéhe, also spelled Woqini and Woquini), was a Native American of the Northern Cheyenne. He is considered to be one of, if not the greatest and most influential war ...

. Most of these bands also agreed to go in to the Spotted Tail Agency to surrender. Crazy Horse was not in the camp, but his father gave a horse to a member of the delegation, as evidence that the Oglala war leader was ready to surrender.

Johnny Brughier mission

Not to be outdone by General Crook's diplomatic efforts, Colonel Miles sent out a peace initiative from his Tongue River Cantonment. Scout Johnny Brughier, aided by two captive Cheyenne women, found the Northern Cheyenne village on the Little Bighorn. They met in councils for several days. His effort would lead to a large contingent of Northern Cheyenne eventually surrendering at the Tongue River Cantonment.Red Cloud mission

On April 13, a second delegation departed theRed Cloud Agency

The Red Cloud Agency was an Indian agency for the Oglala Lakota as well as the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, from 1871 to 1878. It was located at three different sites in Wyoming Territory and Nebraska before being moved to South Dakota. It w ...

, led by the noted Oglala leader Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

, with nearly 70 other members of various bands. This delegation met Crazy Horse's people ''en route'' to the agency to surrender and accompanied them most of the way in.

Surrenders

The continuous military campaigns and the intensive diplomatic efforts finally began to yield results in the early spring of 1877 as large numbers of northern bands began to surrender. In April 1877, an aide of General Crook's wrote to a friend: "I am now fully satisfied that the great Sioux War is now ended and that we will have once more a chance to have peace." A large number of Northern Cheyenne, led byDull Knife

Morning Star (Cheyenne: ''Vóóhéhéve''; also known by his Lakota Sioux name ''Tȟamílapȟéšni'' or its translation, Dull Knife) (1810–1883) was a great chief of the Northern Cheyenne people and headchief of the ''Notameohmésêhese'' ("N ...

and Standing Elk, surrendered at the Red Cloud Agency on April 21, 1877. They were shipped to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

the following month. Touch the Clouds

Touch the Clouds ( Lakota: Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagya or Maȟpíya Íyapat'o) (c. 1838 – September 5, 1905) was a chief of the '' Minneconjou'' Teton Lakota (also known as Sioux) known for his bravery and skill in battle, physical strength and ...

and Roman Nose

Roman Nose ( – September 17, 1868), also known as Hook Nose ( chy, Vóhko'xénéhe, also spelled Woqini and Woquini), was a Native American of the Northern Cheyenne. He is considered to be one of, if not the greatest and most influential war ...

arrived with bands at the Spotted Tail Agency. Crazy Horse surrendered with his band at Red Cloud on May 5.

Death of Crazy Horse

The respected Oglala leader Crazy Horse spent several months with his band at the Red Cloud Agency amidst an environment of intense politics. Fearing he was about to break away, the Army moved to surround his village and arrest the leader on September 4, 1877. Crazy Horse slipped away to the Spotted Tail Agency. The following day, Crazy Horse was brought back to Camp Robinson with the promise that he could meet with the post commander. Instead, he was taken to the guard house under arrest. During his struggle to escape, he was fatally bayoneted by a soldier.Flight to Canada

While many of the Lakota surrendered at the various agencies along the Missouri River or in northwestern Nebraska, Sitting Bull led a large contingent across the international border into Canada. General Terry was part of a delegation sent to negotiate with the bands, hoping to persuade them to surrender and return to the US, but they refused. Not until the buffalo were seriously depleted, and troubles began to surface with other native tribes in Canada, did they finally return. In 1880–81, most of the Lakota from Canada surrendered atFort Keogh

Fort Keogh is a former United States Army post located at the western edge of modern Miles City, in the U.S. state of Montana. It is situated on the south bank of the Yellowstone River, at the mouth of the Tongue River.

Colonel Nelson A. Miles, ...

and Fort Buford

Fort Buford was a United States Army Post at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers in Dakota Territory, present day North Dakota, and the site of Sitting Bull's surrender in 1881.Ewers, John C. (1988): "When Sitting Bull Surrendere ...

. US forces transferred them by steamboat to the Standing Rock Agency 1881.

Aftermath

The Great Sioux War of 1876–77 contrasted sharply withRed Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War or the Powder River War) was an armed conflict between an alliance of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho peoples against the United States that took place in the Wyoming and Mo ...

fought a decade earlier. During the 1860s, Lakota leaders enjoyed wide support from their bands for the fighting. By contrast, in 1876–77, nearly two-thirds of all Lakota had settled at Indian agencies to accept rations and gain subsistence. Such bands did not support or participate in the fighting.

The deep political divisions within the Lakota continued well into the early reservation period, affecting native politics for several decades. In 1889–90, the rise of the Ghost Dance movement found a large majority of its followers among the non-agency bands who had fought in the Great Sioux War.

While much more numerous in total population, the bands of the Lakota generally were independent and made separate decisions about warfare. Many bands did ally with the Cheyenne, and there was intermarriage between the tribes. An alternative view is that the Plains Indians considered the war of 1876–77 to be "The Great Cheyenne War".

References

External links

Map: Prelude to the Great Sioux War of 1876

{{DEFAULTSORT:Great Sioux War Of 1876-77 Black Hills Cheyenne tribe Conflicts in 1876 Conflicts in 1877 1876 in Dakota Territory Indian wars of the American Old West Wars involving the indigenous peoples of North America Lakota Montana Territory Native American history of Montana Native American history of Nebraska Native American history of Oklahoma Native American history of South Dakota Native American history of Wyoming Sioux Wars Wars between the United States and Native Americans Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant 1877 in Dakota Territory