Great Seljuk Architecture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Great Seljuk architecture, or simply Seljuk architecture, refers to building activity that took place under the Great Seljuk Empire (11th–12th centuries). The developments of this period contributed significantly to the architecture of Iran, the architecture of Central Asia, and that of nearby regions. It introduced innovations such as the symmetrical four-iwan layout in mosques, advancements in dome construction, early use of ''muqarnas'', and the first widespread creation of state-sponsored madrasas. Their buildings were generally constructed in

The most important religious monument from the Great Seljuk period is the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, which was expanded and modified by various Seljuk patrons in the late 11th century and early 12th century. Two major and innovative

The most important religious monument from the Great Seljuk period is the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, which was expanded and modified by various Seljuk patrons in the late 11th century and early 12th century. Two major and innovative

File:Rabat-i Malik caravanserai 2 (cropped and retouched).jpg, Entrance portal of the Ribat-i Malik caravanserai on the road between

File:Kharaghan.jpg,

The scarcity of wood on the Iranian Plateau led to the prominence of

The scarcity of wood on the Iranian Plateau led to the prominence of  While brick decoration favoured geometric motifs,

While brick decoration favoured geometric motifs,  The 11th century saw the spread of the ''muqarnas'' technique of decoration across the Islamic world, although its exact origins and the manner in which it spread is not fully understood by scholars. Muqarnas was used for vaulting and to accomplish transitions between different structural elements, such as the transition between a square chamber and a round dome (squinches). Examples of early muqarnas squinches are found in Iranian and Central Asian monuments during previous centuries, but deliberate and significant use of fully-developed muqarnas is visible in Seljuk structures such as in the additions to the Friday Mosque in Isfahan.

A traditional sign of the Seljuks used in their architecture was an eight-pointed star that held a philosophic significance, being regarded as the symbol of existence and eternal evolution. Many examples of this Seljuk star can be found in tile work, ceramics and rugs from the Seljuk period and the star has even been incorporated in the state emblem of Turkmenistan. Another typical Seljuk symbol is the ten-fold rosette or the large number of different types of rosettes on Seljuk

The 11th century saw the spread of the ''muqarnas'' technique of decoration across the Islamic world, although its exact origins and the manner in which it spread is not fully understood by scholars. Muqarnas was used for vaulting and to accomplish transitions between different structural elements, such as the transition between a square chamber and a round dome (squinches). Examples of early muqarnas squinches are found in Iranian and Central Asian monuments during previous centuries, but deliberate and significant use of fully-developed muqarnas is visible in Seljuk structures such as in the additions to the Friday Mosque in Isfahan.

A traditional sign of the Seljuks used in their architecture was an eight-pointed star that held a philosophic significance, being regarded as the symbol of existence and eternal evolution. Many examples of this Seljuk star can be found in tile work, ceramics and rugs from the Seljuk period and the star has even been incorporated in the state emblem of Turkmenistan. Another typical Seljuk symbol is the ten-fold rosette or the large number of different types of rosettes on Seljuk

brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

, with decoration created using brickwork, tiles, and carved stucco.

Historical background

The Seljuk Turks created the Great Seljuk Empire in the 11th century, conquering all of Iran and other extensive territories from the Hindu Kush to eastern Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. In 1050Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

was established as capital of the Great Seljuk Empire under Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan was the second Sultan of the Seljuk Empire and great-grandson of Seljuk, the eponymous founder of the dynasty. He greatly expanded the Seljuk territory and consolidated his power, defeating rivals to the south and northwest, and his v ...

. In 1071, following the Seljuk victory over the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert

The Battle of Manzikert or Malazgirt was fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire on 26 August 1071 near Manzikert, theme of Iberia (modern Malazgirt in Muş Province, Turkey). The decisive defeat of the Byzantine army and th ...

, Anatolia was opened up to Turkic

Turkic may refer to:

* anything related to the country of Turkey

* Turkic languages, a language family of at least thirty-five documented languages

** Turkic alphabets (disambiguation)

** Turkish language, the most widely spoken Turkic language

* ...

settlers. The center of Seljuk architectural patronage was Iran, where the first permanent Seljuk edifices were constructed. The cultural apogee of the Great Seljuk state is associated with the reign of Malik-Shah I

Jalāl al-Dawla Mu'izz al-Dunyā Wa'l-Din Abu'l-Fatḥ ibn Alp Arslān (8 August 1055 – 19 November 1092, full name: fa, ), better known by his regnal name of Malik-Shah I ( fa, ), was the third sultan of the Great Seljuk Empire from 1072 to ...

(r. 1072–1092) and the tenure of Nizam al-Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising fro ...

as his vizier. Among other policies, Nizam al-Mulk championed Sunnism

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

over Shiism and founded a network of madrasas as an instrument for this policy. This marked the beginning of the madrasa as an institution that spread across the Sunni Islamic world. Although no Seljuk madrasas have been preserved intact today, the architectural design of Seljuk madrasas in Iran likely influenced the design of madrasas elsewhere.

While the apogee of the Great Seljuks was short-lived, it represents a major benchmark in the history of Islamic art and architecture in the region of Greater Iran

Greater Iran ( fa, ایران بزرگ, translit=Irān-e Bozorg) refers to a region covering parts of Western Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, Xinjiang, and the Caucasus, where both Culture of Iran, Iranian culture and Iranian langua ...

, inaugurating an expansion of patronage and of artistic forms. Much of the Seljuk architectural heritage was destroyed as a result of the Mongol invasions in the 13th century. Nonetheless, compared to pre-Seljuk Iran, a much greater volume of surviving monuments and artifacts from the Seljuk period has allowed scholars to study the arts of this era in much greater depth than preceding periods. The period of the 11th to 13th centuries is also considered a "classical era" of Central Asian architecture, marked by a high quality of construction and decoration. Here the Seljuk capital was Merv, which remained the artistic center of the region during this period. The region of Transoxiana, north of the Oxus, was ruled by the Qarakhanids

The Kara-Khanid Khanate (; ), also known as the Karakhanids, Qarakhanids, Ilek Khanids or the Afrasiabids (), was a Turkic khanate that ruled Central Asia in the 9th through the early 13th century. The dynastic names of Karakhanids and Ilek K ...

, a rival Turkic dynasty who became vassals of the Seljuks during Malik-Shah's reign. This dynasty also contributed to the flourishing of architecture in Central Asia at this time, building in a style very similar to the Seljuks. Similarly, to the east of the Great Seljuk Empire the Ghaznavids

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest ...

and their successors, the Ghurids, built in a closely related style. A general tradition of architecture was thus shared across most of the eastern Islamic world (Iran, Central Asia, and parts of the northern Indian subcontinent) throughout the Seljuk period and its decline, from the 11th to 13th centuries.

After the decline of the Great Seljuks in the late 12th century various Turkic dynasties formed smaller states and empires. A branch of the Seljuk dynasty ruled a Sultanate in Anatolia (also known as the Anatolian Seljuks or Seljuks of Rum), the Zengids

The Zengid dynasty was a Muslim dynasty of Oghuz Turkic origin, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia on behalf of the Seljuk Empire and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to ...

and Artuqids

The Artuqid dynasty (alternatively Artukid, Ortoqid, or Ortokid; , pl. ; ; ) was a Turkoman dynasty originated from tribe that ruled in eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The Artuqi ...

ruled in Northern Mesopotomia (known as the ''Jazira'') and nearby regions, and the Khwarazmian Empire ruled over Iran and Central Asia until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.

Forms and building types

Mosques

The most important religious monument from the Great Seljuk period is the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, which was expanded and modified by various Seljuk patrons in the late 11th century and early 12th century. Two major and innovative

The most important religious monument from the Great Seljuk period is the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, which was expanded and modified by various Seljuk patrons in the late 11th century and early 12th century. Two major and innovative dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

d chambers were added to it in the late 11th century: the south dome (in front of the mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla w ...

) was commissioned by Nizam al-Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising fro ...

in 1086–87 and the north dome was commissioned by Taj al-Mulk

Taj al-Mulk Abu'l Ghana'em Marzban ibn Khosrow Firuz Shirazi ( fa, تاجالملک ابوالغنائم مرزبان بن خسرو فیروز), better simply known as Taj al-Mulk () was a Seljuk Empire, Seljuk courtier during the reigns of Mal ...

in 1088–89. Four large iwans were later erected around the courtyard around the early 12th century, giving rise to the four-iwan plan. These additions constitute some of the most important architectural innovations of the Seljuk period.

The four-iwan plan already had roots in ancient Iranian architecture and has been found in some Parthian and Sasanian palaces. Soon after or around the same time as the Seljuk work in Isfahan, it appeared in other mosques such as the Jameh Mosque of Zavareh (built circa 1135–1136) and the Jameh Mosque of Ardestan (renovated by a Seljuk vizier in 1158–1160). It subsequently became the "classic" form of Iranian Friday (Jameh) mosques.

The transformation of the space in front of the mihrab (or the ''maqsura

''Maqsurah'' ( ar, مقصورة, literally "closed-off space") is an enclosure, box, or wooden screen near the ''mihrab'' or the center of the ''qibla'' wall in a mosque. It was typically reserved for a Muslim ruler and his entourage, and was ori ...

'') into a monumental domed hall also proved to be influential, becoming a common feature of future Iranian and Central Asian mosques. It also features in later mosques in Egypt, Anatolia, and beyond. Both of the domes added to the Isfahan mosque also employ a new type of squinch

In architecture, a squinch is a triangular corner that supports the base of a dome. Its visual purpose is to translate a rectangle into an octagon. See also: pendentive.

Construction

A squinch is typically formed by a masonry arch that spans ...

consisting of a barrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

above a pair of quarter-domes, which was related to early ''muqarnas'' forms. The north dome of the Isfahan mosque, in particular, is considered a masterpiece of medieval Iranian architecture, with the interlacing ribs of the dome and the vertically aligned elements of the supporting walls achieving a great elegance.

Another innovation by the Seljuks was the "kiosk mosque". This usually small edifice is characterised by an unusual plan consisting of a domed hall, standing on arches with three open sides giving it the kiosk

Historically, a kiosk () was a small garden pavilion open on some or all sides common in Iran, Persia, the Indian subcontinent, and in the Ottoman Empire from the 13th century onward. Today, several examples of this type of kiosk still exist ...

character. Furthermore, the minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

s constructed by the Seljuks took a new dimension adopting an Iranian preference of cylindrical form featuring elaborate patterns. This style was substantially different from the typical square shaped North African minarets.

Madrasas

In the late 11th century the Seljuk vizierNizam al-Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising fro ...

(in office between 1064 and 1092) created a system of state madrasas called the ''Niẓāmiyyahs'' (named after him) in various Seljuk and Abbasid cities ranging from Mesopotamia to Khorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

. Practically none of these madrasas founded under Nizam al-Mulk have survived, though partial remains of one madrasa in Khargerd, Iran, include an iwan and an inscription attributing it to Nizam al-Mulk. Nonetheless, it is clear that the Seljuks constructed many madrasas across their empire within a relatively short period of time, thus spreading both the idea of this institution and the architectural models on which later examples were based. Although madrasa-type institutions appear to have existed in Iran before Nizam al-Mulk, this period is nonetheless considered by many as the starting point for the proliferation of the first formal madrasas across the rest of the Muslim world.

André Godard also attributed the origin and spread of the four-iwan plan to the appearance of these madrasas and he argued that the layout was derived from the domestic architecture indigenous to Khorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

. Godard's origin theory has not been accepted by all scholars, but it is widely-attested that the four-iwan layout did spread to other regions alongside the spread of madrasas across the Islamic world.

Caravanserais

Large caravanserais were built as a way to foster trade and assert Seljuk authority in the countryside. They typically consisted of a building with a fortified exterior appearance, monumental entrance portal, and interior courtyard surrounded by various halls, including iwans. Some notable examples, only partly preserved, are the caravanserais of Ribat-i Malik (c. 1068–1080) and Ribat-i Sharaf (12th century) in Transoxiana andKhorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

, respectively.Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

and Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, ...

(c. 1068–1080)

File:Robat Sharaf Caravanserai (cropped).jpg, Ribat-i Sharaf caravanserai in Khorasan (northeastern Iran), built in 1114–1115

Mausoleums

The Seljuks also continued to build "tower tombs", an Iranian building type from earlier periods, such as the so-called Tughril Tower built in Rayy (south of present-day Tehran) in 1139–1140. More innovative, however, was the introduction of mausoleums with a square or polygonal floor plan, which later became a common form of monumental tombs. Early examples of this are the two Kharraqan Mausoleums (1068 and 1093) near Qazvin (northern Iran), which have octagonal forms, and the large Mausoleum of Sanjar (c. 1152) in Merv (present-day Turkmenistan), which has a square base.Kharraqan Towers

The Kharraqan towers (as known as the Kharrakhan or Kharaghan towers) are a pair of mausolea built in 1067 and 1093, in the Kharraqan region of northern Iran, near Qazvin. They are notable for being an early example of geometric ornament, an early ...

, a set of mausoleums built in 1068 and 1093 in Iran

File:تاریخ ری.jpg, Tughril Tower in Rayy, south of present-day Tehran (Iran), built in 1139–1140

File:SultanSanjarMausoleum1.jpg, Mausoleum of Sultan Ahmad Sanjar (c. 1152) in Merv (present-day Turkmenistan)

Materials and decoration

brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

as a construction material, particularly high-quality baked bricks. It also encouraged the development and use of vaults and dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

s to cover buildings, which in turn led to innovations in the methods of structural support for these vaults. The bonding patterns of brickwork were exploited for decorative effect: by combining bricks in different orientations and by alternating between recessed and projecting bricks, different patterns could be achieved. This technique reached its full development during the 11th century. In some cases pieces of glazed tile were inserted into the spaces between bricks to add further color and contrast. The bricks could also be incised with further motifs or to carve inscriptions on the façades of monuments.

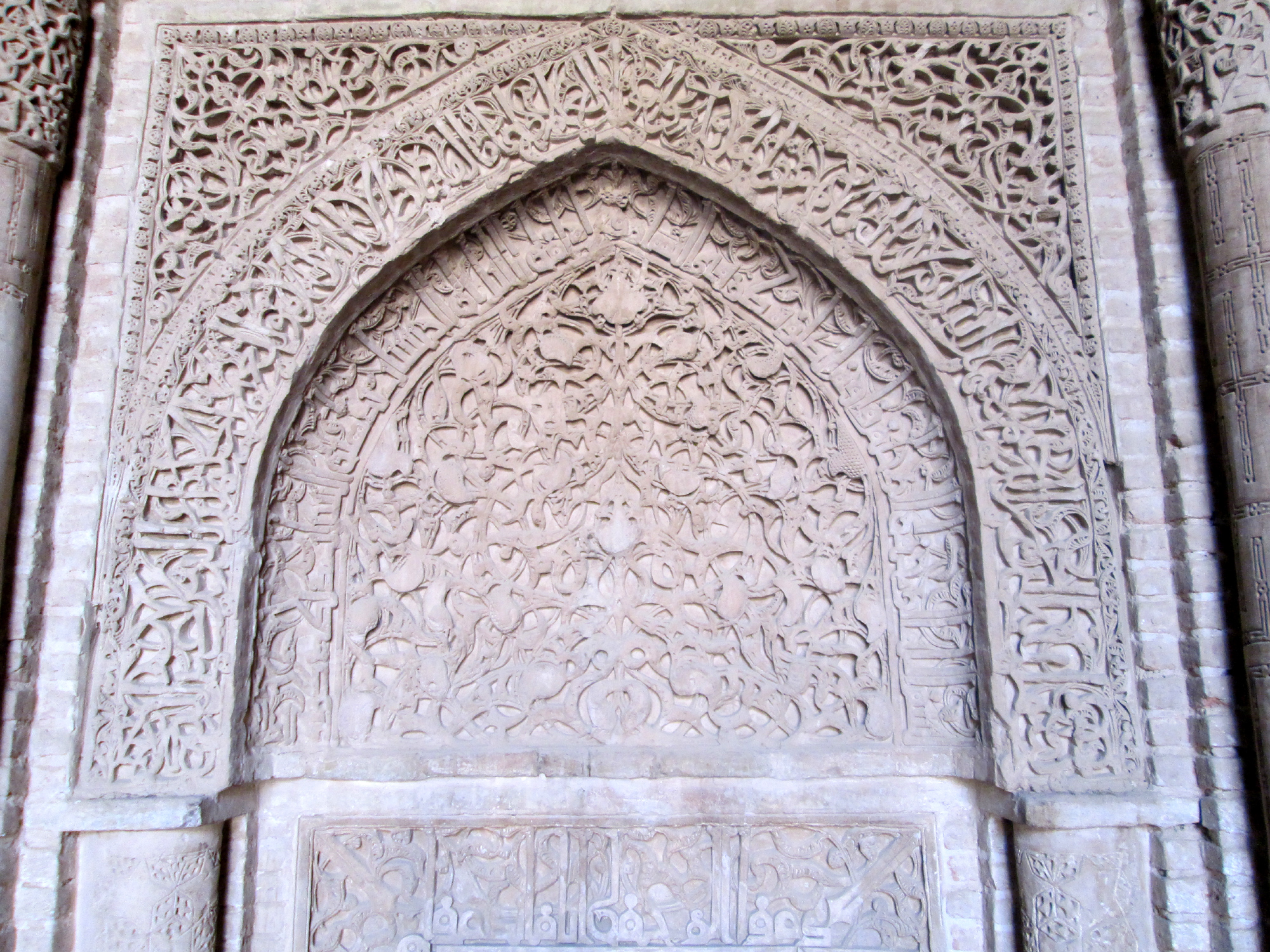

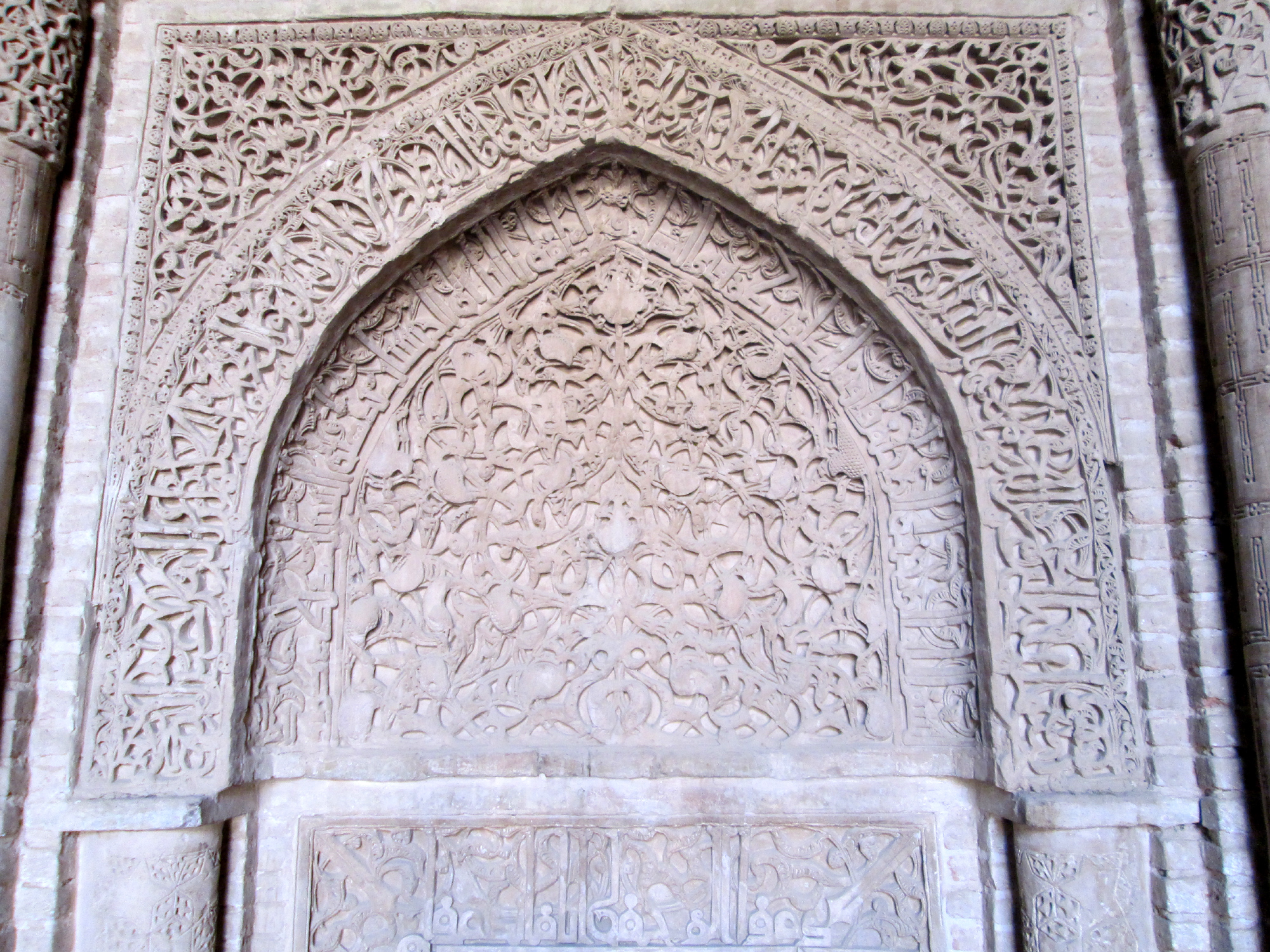

While brick decoration favoured geometric motifs,

While brick decoration favoured geometric motifs, stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

or plaster was also used to cover some surfaces and this material could be carved with a wider range of vegetal and floral motifs ( arabesques). Tilework and color took on increased importance by the late 12th-century and extensive glazed tile decoration appears in multiple 12th-century monuments. This went in hand with a growing trend towards covering walls and large areas with surface decoration that obscured the structure itself. This trend became more pronounced in later Iranian and Central Asian architecture.

The 11th century saw the spread of the ''muqarnas'' technique of decoration across the Islamic world, although its exact origins and the manner in which it spread is not fully understood by scholars. Muqarnas was used for vaulting and to accomplish transitions between different structural elements, such as the transition between a square chamber and a round dome (squinches). Examples of early muqarnas squinches are found in Iranian and Central Asian monuments during previous centuries, but deliberate and significant use of fully-developed muqarnas is visible in Seljuk structures such as in the additions to the Friday Mosque in Isfahan.

A traditional sign of the Seljuks used in their architecture was an eight-pointed star that held a philosophic significance, being regarded as the symbol of existence and eternal evolution. Many examples of this Seljuk star can be found in tile work, ceramics and rugs from the Seljuk period and the star has even been incorporated in the state emblem of Turkmenistan. Another typical Seljuk symbol is the ten-fold rosette or the large number of different types of rosettes on Seljuk

The 11th century saw the spread of the ''muqarnas'' technique of decoration across the Islamic world, although its exact origins and the manner in which it spread is not fully understood by scholars. Muqarnas was used for vaulting and to accomplish transitions between different structural elements, such as the transition between a square chamber and a round dome (squinches). Examples of early muqarnas squinches are found in Iranian and Central Asian monuments during previous centuries, but deliberate and significant use of fully-developed muqarnas is visible in Seljuk structures such as in the additions to the Friday Mosque in Isfahan.

A traditional sign of the Seljuks used in their architecture was an eight-pointed star that held a philosophic significance, being regarded as the symbol of existence and eternal evolution. Many examples of this Seljuk star can be found in tile work, ceramics and rugs from the Seljuk period and the star has even been incorporated in the state emblem of Turkmenistan. Another typical Seljuk symbol is the ten-fold rosette or the large number of different types of rosettes on Seljuk mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla w ...

s and portals that represent the planets which are, according to old central Asian tradition and shamanistic religious beliefs, symbols of the other world. Examples of this symbol can be found in their architecture.The Art and Architecture of Turkey, Ekrem Akurgal, Oxford University Press

See also

* Great Mosque of DiyarbakırNotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * {{History of architecture Islamic architecture Architecture in Iran