Great Lakes Patrol on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Lakes Patrol was carried out by

In 1853 the USS ''Michigan'' was assigned to operate against criminals who were ravaging the logging industry. These so called timber pirates conducted illegal cutting of

In 1853 the USS ''Michigan'' was assigned to operate against criminals who were ravaging the logging industry. These so called timber pirates conducted illegal cutting of  Lieutenant Ransom had only a few seconds to react, and he ordered the ship hard to port. Just as he was ringing the ship's bell to alarm the crew, the unknown ship crashed into the ''Michigan''. Damage to the gunboat was heavy, though because of her iron hull, there was no leaking and the ship was not in danger of sinking. Commander Bigelow later said to

Lieutenant Ransom had only a few seconds to react, and he ordered the ship hard to port. Just as he was ringing the ship's bell to alarm the crew, the unknown ship crashed into the ''Michigan''. Damage to the gunboat was heavy, though because of her iron hull, there was no leaking and the ship was not in danger of sinking. Commander Bigelow later said to

The ''Michigan'' was also involved in the Beaver-Mackinac War. In 1850

The ''Michigan'' was also involved in the Beaver-Mackinac War. In 1850

During the

During the  While Coe was gaining access to the ''Michigan'', Captain Beall was preparing to take over the

While Coe was gaining access to the ''Michigan'', Captain Beall was preparing to take over the

The next conflict involving the patrol was the Fenian Raids into

The next conflict involving the patrol was the Fenian Raids into

Captain

Captain  Some sources say the pirate acted alone. Seavey supposedly provided the ship with alcohol and one night, when most of the crew were drunk, he threw all of them from the ship and sailed the vessel out of the harbor. In response, the captain of the ''Nellie Johnson'' contacted the authorities who dispatched the revenue cutter USRC ''Tuscarora'' to find the ship. The ''Tuscarora'' was a small steam-powered vessel launched in 1901 and she went after the pirates for a few days until they abandoned their

Some sources say the pirate acted alone. Seavey supposedly provided the ship with alcohol and one night, when most of the crew were drunk, he threw all of them from the ship and sailed the vessel out of the harbor. In response, the captain of the ''Nellie Johnson'' contacted the authorities who dispatched the revenue cutter USRC ''Tuscarora'' to find the ship. The ''Tuscarora'' was a small steam-powered vessel launched in 1901 and she went after the pirates for a few days until they abandoned their

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

naval forces, beginning in 1844, mainly to suppress criminal activity

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Can ...

and to protect the maritime border with Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. A small force of United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, Coast Guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with customs and security duties to ...

, and Revenue Service

A revenue service, revenue agency or taxation authority is a government agency responsible for the intake of government revenue, including taxes and sometimes non-tax revenue. Depending on the jurisdiction, revenue services may be charged with t ...

ships served in the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

throughout these operations. Through the decades, they were involved in several incidents with pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s and rebel

A rebel is a participant in a rebellion.

Rebel or rebels may also refer to:

People

* Rebel (given name)

* Rebel (surname)

* Patriot (American Revolution), during the American Revolution

* American Southerners, as a form of self-identification; s ...

s.

The patrol was ended in 1920 when the US Coast Guard assumed full command of the operations as part of the Rum Patrol

The Rum Patrol was an operation of the United States Coast Guard to interdict liquor smuggling vessels, known as "rum runners" in order to enforce prohibition in American waters. On 18 December 1917, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was sub ...

. This was initiated during the Prohibition era

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacturing, manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption ...

to try to reduce or end liquor smuggling from Canada across the rivers and lakes, a difficult task: the Canada–United States border

The border between Canada and the United States is the longest international border in the world. The terrestrial boundary (including boundaries in the Great Lakes, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts) is long. The land border has two sections: Can ...

is 8,891 kilometers (5,525 mi) long.

Operations

Origin

The USS ''Michigan'' led the patrol, mostly singlehandedly, from its beginning on October 1, 1844 until the ship was retired in 1912. ''Michigan'' was the only Americangunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

to patrol the vast Great Lakes. She was the first steam-powered, iron-hulled warship of the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

. The ''Michigan'' was built to defend the lakes due to the construction of two British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

steamers during the Canadian rebellions in 1837.

Based in Erie

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 a ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

throughout her career, the gunboat was commissioned on September 29, 1844 under Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

William Inman. Because the Great Lakes are vast inland seas in the north of the continent, during every winter parts of the lakes would freeze over, ending ship traffic. Even when passageways were open, iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

s would make navigation extremely hazardous and difficult. The ''Michigan'' usually sailed from about March to December before heading back for Erie for the winter. A type of house was built there at its mooring to protect the ship from the elements. During the winter, the officers and crew of the ship either stayed at their homes in Erie or at a government-owned hotel near the wharf.

Timber Rebellion

In 1853 the USS ''Michigan'' was assigned to operate against criminals who were ravaging the logging industry. These so called timber pirates conducted illegal cutting of

In 1853 the USS ''Michigan'' was assigned to operate against criminals who were ravaging the logging industry. These so called timber pirates conducted illegal cutting of timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

on federal land and then smuggled

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations.

There are various ...

the valuable commodity out of the area in order to sell it. The areas most affected were in the western Great Lakes region, along the coasts of Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

and Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

. Much of these forested areas controlled by the government were reserved for the building of new warships.

The illegal timber trade centered on Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

. It was nearly as violent as the alcohol trade, which was carried out over the same waters during the Prohibition era

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacturing, manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption ...

of the 1920s. In 1851 the government sent timber agents from the Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

to survey the land and work with local police and naval forces to stop the crime. When loads of wood were found to have been acquired illegally, the agents confiscated it and auctioned it off to the public, and later, in foreign markets. Many of the timber baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

s of the Great Lakes were involved in the illegal trade, and they began stealing back the wood or burning it before it could be shipped away.

Timber agents and smugglers came into conflict on the upper Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. An entirely separate United States Navy operation was conducted along the Calcasieu River

The Calcasieu River ( ; french: Rivière Calcasieu) is a river on the Gulf Coast in southwestern Louisiana. Approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, ...

of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. In 1852 one agent was killed by the pirates while sailing a raft loaded with stolen timber to Dubuque, Iowa

Dubuque (, ) is the county seat of Dubuque County, Iowa, United States, located along the Mississippi River. At the time of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population of Dubuque was 59,667. The city lies at the junction of Iowa, Il ...

. Newspapers such as ''The Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'' and ''The Chicago Democratic Press'' openly advocated armed resistance against the agents. One article in the ''Chicago Tribune'' read as follows; "if they he agentsregard their personal welfare, they had better keep clear of a such transactions as that which they are about to engage in. If men cannot have a law protect their property, they will protect it themselves." The newspapers noted that most of the timber smugglers were from Wisconsin and Illinois, and usually raided Michigan's timberlands, causing much damage to the reserves. When Agent Isaac W. Willard was sent to the Great Lakes in 1853, he observed gangs of timber pirates defy and intimidate federal authorities and burn government-owned property. They burned boats loaded with logs at Grand Haven

Grand Haven is a city within the U.S. state of Michigan and the county seat of Ottawa County. Grand Haven is located on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Grand River, for which it is named. As of the 2010 census, Grand H ...

, as a re-enactment of the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell tea ...

of 1773.

At this time the only American warship on the Great Lakes was the USS ''Michigan'' under Commander Abraham Bigelow. The only other vessel in the lakes which could have been used against the pirates was the revenue cutter

A cutter is a type of watercraft. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig (or sailplan) of a sailing vessel (but with regional differences in definition), to a governmental enforcement agency vessel (such as a coast guard or bor ...

USRC ''Ingham'', described by one Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

newspaper as being "burlesque" and unfit for duty. Because the ''Ingham'' had no steam engine, and was propelled solely by sails and wind, the more advanced steam-powered vessels used by the smugglers, could easily escape her.

In late April the ''Michigan'' headed for Buffalo to resupply before her yearly patrol. After that Commander Bigelow sailed west across Lake Erie, passing north along Detroit on Thursday, May 5, 1853 and then entered Lake Huron

Lake Huron ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. Hydrology, Hydrologically, it comprises the easterly portion of Lake Michigan–Huron, having the same surface elevation as Lake Michigan, to which it is connected by the , Strait ...

via Saint Clair River. On the following morning, at about 2:15 am, a lookout sighted a light in the darkness ahead of the ''Michigan''. The officer on duty, Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

George M. Ransom, ordered the helmsman

A helmsman or helm (sometimes driver) is a person who steering, steers a ship, sailboat, submarine, other type of maritime vessel, or spacecraft. The rank and seniority of the helmsman may vary: on small vessels such as fishing vessels and yacht ...

to steer north by northwest, so as to avoid the light, but by 2:40 am the light was still ahead and "close upon us", according to one sailor. At 3:00 am the two ships were only a few hundred yards from each other and it appeared as though the two would pass closely by. However, the unknown ship suddenly turned ninety degrees to port side and headed straight for the ''Michigan''s port bow.

Lieutenant Ransom had only a few seconds to react, and he ordered the ship hard to port. Just as he was ringing the ship's bell to alarm the crew, the unknown ship crashed into the ''Michigan''. Damage to the gunboat was heavy, though because of her iron hull, there was no leaking and the ship was not in danger of sinking. Commander Bigelow later said to

Lieutenant Ransom had only a few seconds to react, and he ordered the ship hard to port. Just as he was ringing the ship's bell to alarm the crew, the unknown ship crashed into the ''Michigan''. Damage to the gunboat was heavy, though because of her iron hull, there was no leaking and the ship was not in danger of sinking. Commander Bigelow later said to Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

James Cochran Dobbin; "Had the Michigan been built of wood instead of iron, there is no doubt but that she would have been cut down before the water's edge and sunk." The other ship bounced off the ''Michigan''s metal hull just after impact, and her commander turned his ship back onto course and continued on without stopping. This angered Bigelow, who proceeded to chase the fleeing steamer. After a brief pursuit, the American gunboat was close enough to the steamer for her crew to read the vessel's nameboard. The steamer proved to be the ''Buffalo''; at the time, she was the largest steam-powered timber ship to sail the lakes. She was owned by a Mr. Walbridge and was headed for Chicago.

Though Lieutenant Ransom felt the ramming was deliberate, Commander Bigelow thought it must have been an accident. He brought his ship alongside the ''Buffalo'' and asked if the crew of the steamer needed any assistance. The crew answered to the negative so Bigelow let the ship go, but he followed it into Chicago for repairs. While it is not certain that the ramming was intentional or not, Bigelow endeavored to find evidence that it was. The commander filed a lawsuit against Mr. Walbridge: either his ship's captain had been irresponsible or he was trying to sink the ''Michigan''.

The crew of the merchant ship ''Republic'' witnessed the ''Buffalo'' swerve off course to ram the gunboat, and the ship's captain submitted his report in writing; however, because the evidence was circumstantial, the case never went to trial. USS ''Michigan'' was put out of action for two months for repairs, which cost $1,674 to complete. Over the course of the next few weeks after refitting, the ''Michigan'' captured several timber pirates with the assistance of Agent Willard and a Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

detachment. These operations are credited with ending the 1853 Timber Rebellion in a federal victory. But the illegal logging

Illegal logging is the harvest, transportation, purchase or sale of timber in violation of laws. The harvesting procedure itself may be illegal, including using corrupt means to gain access to forests; extraction without permission, or from a pro ...

trade continued to as late as the 1870s.

Beaver-Mackinac War

The ''Michigan'' was also involved in the Beaver-Mackinac War. In 1850

The ''Michigan'' was also involved in the Beaver-Mackinac War. In 1850 James Strang

James Jesse Strang (March 21, 1813 – July 9, 1856) was an American religious leader, politician and self-proclaimed monarch. In 1844 he claimed to have been appointed to be the successor of Joseph Smith as leader of the Church of Jesus Christ o ...

crowned himself the king of Beaver Island, at the head of Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

. Eventually he began forcing his radical beliefs on some of his mainstream Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

followers, known as Strangites. The commander of the ''Michigan'' was ordered to arrest Strang in May 1851, which was done without conflict. Strang was held in custody for some time and then released, but on Monday, June 16, 1856, he was assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

at St. James, in front of the ''Michigan''. Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Charles H. McBlair

Charles H. McBlair (1809-1890) was the eleventh adjutant general of Maryland. He was an officer in the United States Navy, and during the American Civil War commanded a number of Confederate warships.

Biography Early career, US Navy

McBlair was ...

, commander of the gunboat, had invited the king aboard the ship. He was shot in the back with a pistol at close range as he was waiting on the docks. The assassins, Alexander Wentworth and "Dr. J. Atkyn ic, who were said to be blackmailing the Strangites, fled to the ''Michigan'' for sanctuary. They were later released at Mackinaw without being charged. Strang was shot three times, once in the head, but survived for three weeks before dying on July 9 from his injuries.

The Mormons assumed that Captain McBlair knew about the plot beforehand. Others accused him of being in on it. On July 5, a large mob from Michigan landed on Beaver Island and forcibly removed nearly 3,000 inhabitants with small steam boats. Many people were robbed first in what Byron M. Cutcheon

Byron Mac Cutcheon (May 11, 1836 – April 12, 1908) was an American Civil War officer, Medal of Honor recipient and politician from the U.S. state of Michigan.

Early life

Cutcheon was born in Pembroke, New Hampshire May 11, 1836 but his parents ...

later called "the most disgraceful day in Michigan history". The Mormons were taken to Voree, where some of them stayed while most others dispersed across the country. Beaver Island was later reoccupied by Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

s, who established a colony that flourished in the 1860s and 1870s.

American Civil War

During the

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, USS ''Michigan'' kept up with her yearly patrol against smugglers and other criminals. At that time the gunboat was still the only American warship in those waters, other than six revenue cutters, which were largely ineffective in their operations against crime. Because the Civil War had such a high mortality rate, the government enforced a military draft

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

. There were draft riots by working-class men who resented being sent to war when wealthier men could buy their way out. The most notable one was in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, where largely ethnic Irish attacked African Americans as the scapegoats for their anger. A race riot

This is a list of ethnic riots by country, and includes riots based on ethnic, sectarian, xenophobic, and racial conflict. Some of these riots can also be classified as pogroms.

Africa

Americas

United States

Nativist period: 1700s� ...

took place in Detroit in 1863, also about labor and economic competition issues at bottom, and another in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

. The USS ''Michigan'' spent much of the war patrolling back and forth between those urban areas.

By 1863 Johnson's Island

Johnson's Island is a island in Sandusky Bay, located on the coast of Lake Erie, from the city of Sandusky, Ohio. It was the site of a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederate officers captured during the American Civil War. Initially, Johnson ...

in Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

was used as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

camp for Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

s. The Southern government knew of the camp. In 1863 Lieutenant William Henry Murdaugh of the Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

suggested to President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

a plan to gain control of the lakes by capturing the ''Michigan''. Ultimately Murdaugh's plan was never implemented. But in 1864 Davis authorized Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Charles H. Cole of the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

to go to the Great Lakes with Captain John Yates Beall

John Yates Beall (January 1, 1835 – February 24, 1865) was a Confederate privateer in the American Civil War who was arrested as a spy in New York and executed at Fort Columbus on Governors Island.

Early life and education

Beall was born in ...

and organize the escape of prisoners from Johnson's Island and Camp Chase

Camp Chase was a military staging and training camp established in Columbus, Ohio in May 1861 after the start of the American Civil War. It also included a large Union-operated prison camp for Confederate prisoners during the American Civil War ...

.

Captain Cole had been a prisoner at Johnson's Island before his escape, so he knew the area and the people well. With Beall, Cole collected thirty-five volunteers to take over the ''Michigan''. He cunningly befriended several of the gunboat's officers. Cole also contacted with the Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It pl ...

, a secret society

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

that sympathized with the Confederate cause. The captain organized the successful infiltration of the 128th Ohio Infantry Regiment which guarded the prison camps. Ten of his volunteers posed as Union troops, with orders to assist in the capture of Johnson's Island after the ''Michigan'' had been secured.

On September 19, 1864, the rebels launched their attack. That night Captain Cole went aboard the ''Michigan'' at Sandusky to dine with his 'friends" while waiting for Captain Beall and the volunteers to arrive in a captured merchant ship. The Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

knew all about the plot from a Confederate colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

at Johnson's Islands, who had learned of the Cole's plan and informed the prison guards. The colonel did not know when the attack would take place, but the men of USS ''Michigan'' were ordered to stay on high alert.

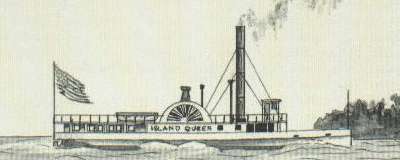

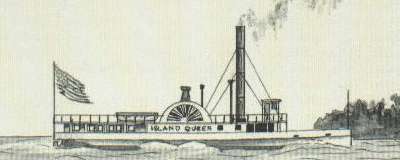

While Coe was gaining access to the ''Michigan'', Captain Beall was preparing to take over the

While Coe was gaining access to the ''Michigan'', Captain Beall was preparing to take over the ferry

A ferry is a ship, watercraft or amphibious vehicle used to carry passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo, across a body of water. A passenger ferry with many stops, such as in Venice, Italy, is sometimes called a water bus or water taxi ...

''Philo Parsons''. The ferry cruised between American and Canadian ports on Lake Erie. Beall separated his men into small groups who boarded the ''Philo Parsons'' as passengers in Canada. When all of the volunteers were aboard, Captain Beall waited until after the ship had left Kellys Island, Ohio to take over the ship. He accomplished this without bloodshed. Beall allowed the passengers to leave, including several recently discharged men from the 130th Ohio Infantry. A little later, as the rebels were sailing to meet with Captain Coe and the ''Michigan'', a steamer named ''Island Queen'' came alongside the ''Philo Parsons''. A sailor tied the two vessels together. When the rebels realized this, they attacked the ''Island Queen'', and a brief gunfight erupted between Beall's men and the steamer's crew. One man was wounded in what was the northernmost naval skirmish of the war. The rebels tried to sail the ship with the ''Philo Parsons'' on to Sandusky. But, at a position three miles off Middle Hull Island, Captain Beall ordered the ''Island Queen'' to be run aground on a reef and burned.

About the same time, seventeen members of the Confederate boarding party became convinced that the Union knew what they were up to, so they refused to participate any further. As result, Beall abandoned his cruise. Thus the plot to capture the ''Michigan'' and liberate the prisoners on Johnson's Island failed before it really began.

Rebel activity in the North did not end. Confederate agents in Canada launched an expedition to the coastal town of St. Albans, Vermont across Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type =

, ...

, one month after the incident on Lake Erie. The rebels, under Lieutenant Bennett H. Young

Bennett Henderson Young (May 25, 1843 – February 23, 1919) was a Confederate officer who led forces in the St Albans raid (October 19, 1864), a military action during the American Civil War. As a lieutenant of the Confederate States Army, he en ...

, robbed two banks and killed or wounded three civilians.

Fenian Raids

The next conflict involving the patrol was the Fenian Raids into

The next conflict involving the patrol was the Fenian Raids into Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

by Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

rebels from the United States. Fenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood, secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries dedicated ...

volunteers, many of whom were veterans of the American Civil War, organized a small army spread out across the international border. There were five notable raids in between 1866 and 1871, all launched from the United States, against British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

targets. The Fenians, who spit into two rival factions, were under the leadership of John O'Mahony

John Francis O'Mahony (1815 – 7 February 1877) was a Gaels, Gaelic scholar and the founding member of the Fenian Brotherhood in the United States, sister organisation to the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Despite coming from a reasonably weal ...

and the more violent group under William R. Roberts

William Randall Roberts (February 6, 1830 – August 9, 1897) was a Fenian Brotherhood member, United States Representative from New York (1871–1875), and a United States Ambassador to Chile. Roberts, an Irish immigrant who became a we ...

. Both were of the opinion that if they could launch a successful invasion of British territory they could force the British to cede their political control over Ireland. The first notable raid was launched in 1866 by about 700 men of O'Mahony's faction. They crossed the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

border from Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

and attacked Campobello Island

Campobello Island (, also ) is the largest and only inhabited island in Campobello, a civil parish in southwestern New Brunswick, Canada, near the border with Maine, United States. The island's permanent population in 2021 was 949. It is the si ...

. When the American government learned of this they sent a force to the island which dispersed the rebels. Shortly after Robert's followers attacked Ridgeway, Ontario

Ridgeway is a small, unincorporated village in Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada. The community is within the Niagara Regional Municipality, Ontario, Niagara Regional Municipality. It used to be the seat of government for Bertie Township within Welland ...

and Fort Erie

Fort Erie is a town on the Niagara River in the Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada. It is directly across the river from Buffalo, New York, and is the site of Old Fort Erie which played a prominent role in the War of 1812.

Fort Erie is one of Ni ...

. At the Battle of Ridgeway

The Battle of Ridgeway (sometimes the Battle of Lime Ridge or Limestone Ridge) was fought in the vicinity of the town of Fort Erie across the Niagara River from Buffalo, New York, near the village of Ridgeway, Canada West, currently Ontario, Ca ...

, on June 2, about 750 Fenians under Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

, James O'Neill, routed a force of 850 Canadian troops.

The battle was the largest during the raids and the first Industrial era engagement to have involved the Canadian military. It was also the last battle in Ontario against a foreign invasion. After that the rebels attacked Fort Erie the same day and forced its surrender. In all the Fenians lost about ten men killed and twenty wounded in the two battles while the Canadians lost nine killed and forty-three wounded, as well as fifty-nine men captured. Fearing that the British Army would arrive soon, O'Neill tried to cross the Niagara River

The Niagara River () is a river that flows north from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario. It forms part of the border between the province of Ontario in Canada (on the west) and the state of New York (state), New York in the United States (on the east) ...

, back into New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

but the men of USS ''Michigan'' were waiting for them. The gunboat, had arrived the day before to intercept rebel reinforcements and her crew accepted the surrender of hundreds of Fenians. Meanwhile, General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, a future American president, and General George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate States Army, Confederate Full General (CSA), General Robert E. Lee at the Battle ...

went to Buffalo to examine the situation, prevent further raids, and disarm the rebels. They coordinated their operations with the USS ''Michigan'' which helped lead to the capture of General Thomas William Sweeny

Thomas William Sweeny (December 25, 1820 – April 10, 1892) was an Irish-American soldier who served in the Mexican–American War and then was a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Birth and early years

Sweeny was bo ...

who was in overall command of the invasion and guilty of violating American neutrality. However, Sweeny had only recently been a Union commander in the Civil War so he was released from custody not long after his arrest.

''Nellie Johnson'' Mutiny

Captain

Captain Dan Seavey

Dan Seavey, also known as "Roaring" Dan Seavey, (March 23, 1865 – February 14, 1949) was a sailor, fisherman, farmer, saloon keeper, prospector, U.S. marshal, thief, poacher, smuggler, hijacker, human trafficker, and timber pirate in Wisconsi ...

is the most remembered pirate to sail the Great Lakes. He was born in 1867 and briefly served in the United States Navy before becoming a criminal. Seavey was known as a fighting man for many exploits, including bar fights and episodes of that nature. His ship was the small fourteen-ton topsail schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

named ''Wanderer'', which was allegedly armed with a cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

at one point. She was built around 1900 and originally intended for the Pabst family who owned the Pabst Brewing Company

The Pabst Brewing Company () is an American company that dates its origins to a brewing company founded in 1844 by Jacob Best and was, by 1889, named after Frederick Pabst. It is currently a holding company which contracts the brewing of over ...

. It is not known how Seavey acquired her. Other than sneaking into a port at night and stealing freight from the docks, Captain Seavey had several different, legitimate professions over the course of his lifetime. He owned a saloon at one point, worked in the timber trade, and participated in the Yukon Gold Rush from 1896 to 1899. Seavey also claimed to have sunk a rival fishing ship with his cannon, killing everyone on board. While it is not known if this story is true, according to author Fred Neuschel

Fred may refer to:

People

* Fred (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Mononym

* Fred (cartoonist) (1931–2013), pen name of Fred Othon Aristidès, French

* Fred (footballer, born 1949) (1949–2022), Frederico R ...

, Seavey was guilty of manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

at least. The most remembered story of the pirate was that of the schooner ''Nellie Johnson'', on which Seavey was a crewman. In 1908, Seavey was serving on the ''Nellie Johnson'' when he decided to incite two of his fellow crew members to mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

and take the schooner from either Grand Haven, Michigan or Chicago, depending on varying sources.

Some sources say the pirate acted alone. Seavey supposedly provided the ship with alcohol and one night, when most of the crew were drunk, he threw all of them from the ship and sailed the vessel out of the harbor. In response, the captain of the ''Nellie Johnson'' contacted the authorities who dispatched the revenue cutter USRC ''Tuscarora'' to find the ship. The ''Tuscarora'' was a small steam-powered vessel launched in 1901 and she went after the pirates for a few days until they abandoned their

Some sources say the pirate acted alone. Seavey supposedly provided the ship with alcohol and one night, when most of the crew were drunk, he threw all of them from the ship and sailed the vessel out of the harbor. In response, the captain of the ''Nellie Johnson'' contacted the authorities who dispatched the revenue cutter USRC ''Tuscarora'' to find the ship. The ''Tuscarora'' was a small steam-powered vessel launched in 1901 and she went after the pirates for a few days until they abandoned their prize

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

and escaped to shore. According to Neuschel, there are several exaggerated accounts of the chase. Some said that the ''Tuscarora'' found Seavey and opened fire, but the captain was able to steer the schooner out harm's way. Others said that after a warning shot Seavey surrendered and the ''Nellie Johnson'' was boarded by the ''Tuscarora''s crew. Neither story is true. Seavey was eventually apprehended on land by a United States Marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforcem ...

. He was arrested for "''mutiny and revolt''" but was released when the ship's owner failed to press charges. Seavey became a marshal himself and he is generally accepted to have retired to his home somewhere around Beaver Island in the 1920s.Neuschel, pp. 147-8

See also

*Yangtze Patrol

The Yangtze Patrol, also known as the Yangtze River Patrol Force, Yangtze River Patrol, YangPat and ComYangPat, was a prolonged naval operation from 1854–1949 to protect American interests in the Yangtze River's treaty ports. The Yangtze P ...

*African Slave Trade Patrol

African Slave Trade Patrol was part of the Blockade of Africa suppressing the Atlantic slave trade between 1819 and the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861. Due to the abolitionist movement in the United States, a squadron of U.S. Navy ...

*Neutrality Patrol

On September 3, 1939, the British and French declarations of war on Germany initiated the Battle of the Atlantic. The United States Navy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) established a combined air and ship patrol of the United States Atlantic coa ...

* Ice Patrol

*Gunboat diplomacy

In international politics, the term gunboat diplomacy refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to th ...

References

* * {{Pirates History of the Midwestern United States Maritime history of the United States United States Navy in the 19th century United States Navy in the 20th century United States Navy and Coast Guard patrols Maritime incidents in 1853 Maritime incidents in 1856 Maritime incidents in 1864 Maritime incidents in 1866 Maritime incidents in 1908 Naval operations and battles Great Lakes