Great Cause on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

When the

/ref> Balliol also argued that the Kingdom of Scotland was, as royal estate, indivisible as an entity. This was necessary to prevent the kingdom being split equally amongst the heirs as Hastings was suggesting should be done. Robert de Brus (also spelled Bruce), Lord of Annandale, had the best claim to the throne according toMorris, Marc, ''A Great and Terrible King'' (2010), pp.258-259

/ref> However, Floris's case was this time rejected for lack of evidence: despite the long interim since his earlier request for an adjournment, he was unable to produce evidence of his claim—due, he claimed, to theft of the vital documents. His claim was this time thrown out for lack of evidence.Morris, Marc, ''A Great and Terrible King'' (2010), p.259

/ref> Copies of the documents he sought would later surface at

crown of Scotland

The Crown of Scotland ( gd, Crùn na h-Alba) is the crown that was used at the coronation of the monarchs of Scotland. It is the oldest surviving crown in the British Isles and dates from at least 1503, although it has been claimed that the ...

became vacant in September 1290 on the death of the seven-year-old Queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

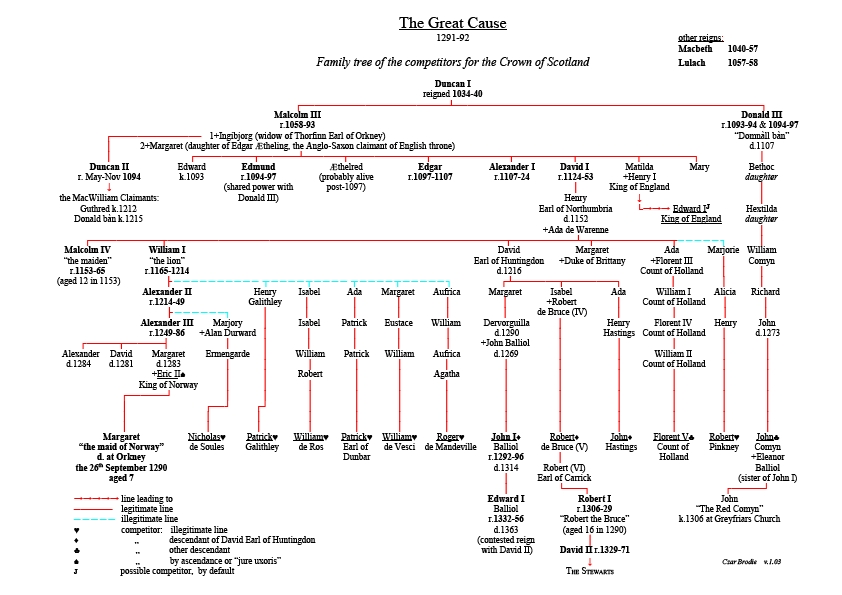

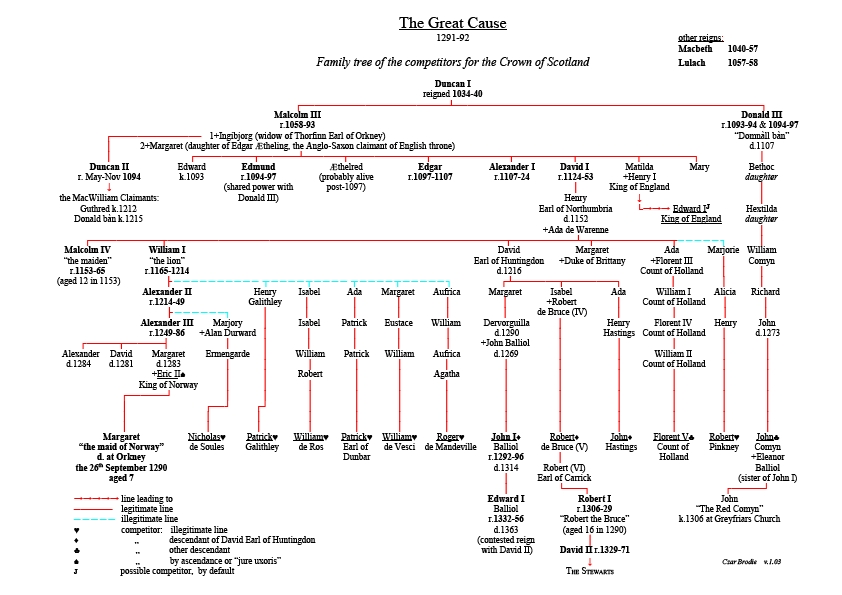

, 13 claimants to the throne came forward. Those with the most credible claims were John Balliol, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, John Hastings and Floris V, Count of Holland

Floris V (24 June 1254 – 27 June 1296) reigned as Count of Holland and Zeeland from 1256 until 1296. His life was documented in detail in the Rijmkroniek by Melis Stoke, his chronicler. He is credited with a mostly peaceful reign, modern ...

.

Fearing civil war, the Guardians of Scotland

The Guardians of Scotland were regents who governed the Kingdom of Scotland from 1286 until 1292 and from 1296 until 1306. During the many years of minority in Scotland's subsequent history, there were many guardians of Scotland and the post was ...

asked Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Duchy of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and D ...

to arbitrate. Before agreeing, he obtained concessions going some way to revive English overlordship over the Scots. A commission of 104 "auditors" was then appointed—24 by Edward himself, acting as president; and the rest by Bruce and Balliol, in equal numbers. In November 1292, the body decided in favour of John Balliol, whose claim was based on the traditional criterion of primogeniture—inheritance through a line of firstborn sons. The decision was accepted by the majority of the powerful in Scotland, and John ruled as King of Scots

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have grown ...

from then until 1296.

Background

With the death ofKing Alexander III

Alexander III (Medieval ; Modern Gaelic: ; 4 September 1241 – 19 March 1286) was King of Scots from 1249 until his death. He concluded the Treaty of Perth, by which Scotland acquired sovereignty over the Western Isles and the Isle of Man. His ...

in 1286, the crown of Scotland passed to his only surviving descendant, his three-year-old granddaughter Margaret (the Maid of Norway). In 1290, the Guardians of Scotland

The Guardians of Scotland were regents who governed the Kingdom of Scotland from 1286 until 1292 and from 1296 until 1306. During the many years of minority in Scotland's subsequent history, there were many guardians of Scotland and the post was ...

, who had been appointed to govern the realm during the young Queen's minority

Minority may refer to:

Politics

* Minority government, formed when a political party does not have a majority of overall seats in parliament

* Minority leader, in American politics, the floor leader of the second largest caucus in a legislative b ...

, drew up the Treaty of Birgham, a marriage contract between Margaret and the five-year-old Edward of Caernarfon

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to ...

, heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the English throne. The treaty, amongst other points, contained the provision that although the issue of this marriage would inherit the crowns of both England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and Scotland, the latter kingdom should be "separate, apart and free in itself without subjection to the English Kingdom".Powicke, Maurice, ''The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1307'', 1963, The intent was to keep Scotland an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

entity.

Margaret died on 26 September 1290 in Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) nort ...

on her way to Scotland, leaving the throne vacant. The Guardians called upon her fiancé's father, Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Duchy of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and D ...

, to conduct a court in which 104 auditors would choose from among the various competitors for the Scottish throne in a process known as the Great Cause (). One of the strongest claimants, John Balliol, Lord of Galloway

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered a ...

, forged an alliance with the powerful Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham, the representative of Edward I in Scotland and began styling himself 'heir of Scotland',Stevenson, J., ''Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland'', 1870 while another, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, turned up to the site of Margaret's supposed inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaug ...

with a force of soldiers amidst rumours that his friends the Earl of Mar

There are currently two earldoms of Mar in the Peerage of Scotland, and the title has been created seven times. The first creation of the earldom is currently held by Margaret of Mar, 31st Countess of Mar, who is also clan chief of Clan Mar. ...

and the Earl of Atholl were also raising their forces.Barrow, Geoffrey W.S., ''Robert Bruce & The Community of The Realm of Scotland'', 1988, Scotland looked to be headed for civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

.

Edward I steps in

To avoid the catastrophe of open warfare between the Bruce and Balliol, the Guardians and other Scotsmagnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s asked Edward I to intervene.Simpson, Grant G., and Stones, ELG., ''Edward I and the Throne of Scotland: An Edition of the Record Sources for the Great Cause'', 1979, Edward seized the occasion as an opportunity to gain something he had long desired—legal recognition that the realm of Scotland was held as a feudal dependency to the throne of England. The English kings

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Kingdom of Wessex, Wessex, one of the heptarchy, seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled ...

had a long history of presuming an overlordship of Scotland, harking back to the late 12th century when Scotland had actually been a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. ...

state of Henry II's England for 15 years from 1174 ( Treaty of Falaise) until the Quitclaim of Canterbury (1189), but the legality of Edward's 13th-century claim was questionable. Alexander III, giving homage to Edward, had chosen his words very carefully: "I become your man for the lands I hold of you in the Kingdom of England for which I owe homage, ''saving my Kingdom''"Stones, ELG., ''Anglo-Scottish Relations 1174–1328'', 1970, (author's italics).

In line with this desire, Edward demanded in May 1291 that his claim of feudal overlordship of Scotland be recognised before he would step in and act as arbiter. He demanded that the Scots produce evidence to show that he was not the lawful overlord, rather than presenting them with evidence that he was. The Scots' reply came that without a king there was no one in the realm responsible enough to possibly make such an admission, and so any assurances given by the Scots were worthless. Although technically and legally correct by the standards of the time, this reply infuriated Edward enough that he refused to have it entered on the official record of the proceedings.

The Guardians and the claimants still needed Edward's help, and he did manage to press them into accepting a number of lesser though still important terms. The majority of the competitors and the Guardians did eventually step forward to acknowledge Edward as their rightful overlord, even though they could not be taken as speaking for the realm as a whole. They also agreed to put Edward in temporary control of the principal royal castles of Scotland despite the castles in question not being theirs to give away. For his part, Edward agreed that he would return control of both kingdom and castles to the successful claimant within two months. In the ongoing negotiations between the two countries, the Scots continued to use the Treaty of Birgham as a reference point, indicating that they still wished to see Scotland retain an independent identity from England.

Having got these concessions, Edward arranged for a court to be set up to decide which of the claimants should inherit the throne. It consisted of 104 auditors plus Edward himself as president. Edward chose 24 of the auditors while the two claimants with the strongest cases—Bruce and Balliol—were allowed to appoint forty each.

Competitors

When Margaret died, there were no close relatives to whom the succession might pass in a smooth and clear manner. Of her nearest relatives derived through legitimate descent from prior kings, all but one were the descendants of Margaret's great-great-great-grandfather, Henry, the son of kingDavid I of Scotland

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim ( Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malco ...

; the exception was Edward I himself, who was a descendant of Malcolm Canmore's daughter Matilda of Scotland

Matilda of Scotland (originally christened Edith, 1080 – 1 May 1118), also known as Good Queen Maud, or Matilda of Blessed Memory, was Queen of England and Duchess of Normandy as the first wife of King Henry I. She acted as regent of England ...

. In addition to these relatives, there were noblemen descended from illegitimate daughters of more recent Scottish kings who also made claims. Thirteen nobles put themselves forward as candidates for the throne (with those claiming the throne through illegitimate lines in ''italic''): Massingberd, Hugh Montgomery, ''Burke's Guide to the Royal Family'', 1973, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

: ''Burke's Peerage

Burke's Peerage Limited is a British genealogical publisher founded in 1826, when the Irish genealogist John Burke began releasing books devoted to the ancestry and heraldry of the peerage, baronetage, knightage and landed gentry of Great ...

''

*John Balliol, Lord of Galloway

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered a ...

, son of Devorguilla, daughter of Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

, eldest daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon

David of Scotland (Medieval Gaelic: ''Dabíd'') (1152 – 17 June 1219) was a Scottish prince and 8th Earl of Huntingdon. He was, until 1198, heir to the Scottish throne.

Life

He was the youngest surviving son of Henry of Scotland, 3rd Earl of ...

, son of Henry, Earl of Huntingdon, son of King David I. He pleaded primogeniture in legitimate, cognatic line.

* Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, son of Isabella, second daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon. This Robert Bruce was regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

of Scotland sometime during the minority of King Alexander III and was occasionally recognised as a tanist of the Scottish throne. In the succession dispute, he pleaded tanistry

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist ( ga, Tánaiste; gd, Tànaiste; gv, Tanishtey) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of ...

and proximity in degree of kinship to the previous monarch, his descent being a generation shorter.

*John Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings

John Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings (6 May 1262 – 28 February 1313), feudal Lord of Abergavenny, was an English peer and soldier. He was one of the Competitors for the Crown of Scotland in 1290/92 in the Great Cause and signed and sealed the ...

, son of Henry de Hastings

Henry de Hastings (c. 1235–c. 1268) of Ashill, Norfolk,G. E. Cokayne, ''The Complete Peerage'', n.s., vol.VI, p.345 was a supporter of Simon de Montfort in his rebellion against King Henry III. He led the Londoners at the Battle of Lewes in 12 ...

, son of Ada, third daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon.

*Floris V, Count of Holland

Floris V (24 June 1254 – 27 June 1296) reigned as Count of Holland and Zeeland from 1256 until 1296. His life was documented in detail in the Rijmkroniek by Melis Stoke, his chronicler. He is credited with a mostly peaceful reign, modern ...

, son of William II, Count of Holland

William II (February 1227 – 28 January 1256) was the Count of Holland and Zeeland from 1234 until his death. He was elected anti-king of Germany in 1248 and ruled as sole king from 1254 onwards.

Early life

William was the eldest son and hei ...

, son of Floris IV, Count of Holland, son of William I, Count of Holland, son of Ada, daughter of Henry, Earl of Huntingdon. He claimed that David, Earl of Huntingdon, had renounced his hereditary rights to throne of Scotland.

* John "the Black" Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, son of John Comyn

John Comyn III of Badenoch, nicknamed the Red (c. 1274 – 10 February 1306), was a leading Scottish baron and magnate who played an important role in the First War of Scottish Independence. He served as Guardian of Scotland after the forced ...

, son of Richard Comyn, son of William Comyn, son of Hextilda, daughter of Bethóc, daughter of King Donald III.

*''Nicholas de Soules

Nicholas is a male given name and a surname.

The Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Anglican Churches celebrate Saint Nicholas every year on December 6, which is the name day for "Nicholas". In Greece, the name and it ...

'', son of Ermengarde, daughter of Marjorie, natural daughter of King Alexander II.

*''Patrick Galithly

Patrick Galithly or Patrick Golightly, Burgess of Perth was a 13th-century Scottish official. He was a competitor for the Crown of Scotland.

Upon the death of the Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290, Patrick became one of the competitors for the Cr ...

'', son of Henry Galithly, natural son of King William the Lion.

*'' William de Ros, 1st Baron de Ros'', son of Robert de Ros, son of William de Ros of Hamlake, son of Isabella, natural daughter of King William the Lion.

*'' William de Vesci, Baron de Vesci'', son of William de Vesci, son of Margaret, illegitimate daughter of King William the Lion.

*''Patrick Dunbar, 7th Earl of Dunbar

Patrick IV, 8th Earl of Dunbar and Earl of March (124210 October 1308), sometimes called Patrick de Dunbar "8th" Earl of March, was the most important magnate in the border regions of Scotland. He was one of the Competitors for the Crown of Scotl ...

'', son of Patrick, 6th Earl of Dunbar

Patrick III, 7th Earl of Dunbar ( 121324 August 1289) was lord of the feudal barony of Dunbar and its castle, which dominated East Lothian, and the most important military personage in the Scottish Borders.

Background

Said to be aged 35 in 1248 ...

, son of Patrick, 5th Earl of Dunbar

Patrick II (1185–1249), called "6th Earl of Dunbar", was a 13th-century Anglo-Scottish noble, and one of the leading figures during the reign of King Alexander II of Scotland.

Said to be aged forty-six at the time of his father's death, thi ...

, son of Ada, natural daughter of King William the Lion.

*''Roger de Mandeville

Roger de Mandeville was a prominent 13th-century noble. He was a son of Agatha, daughter of Robert Wardone and Aufrica de Say.

Upon the death of the Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290, Roger became one of the competitors for the Crown of Scotland, d ...

'', son of Agatha, daughter of Aufrica, daughter of William de Say, son of Aufrica, natural daughter of King William the Lion.

*'' Robert de Pinkeney'', son of Henry, son of Alicia, daughter of Marjorie, an alleged natural daughter of Henry, Earl of Huntingdon.

* Eric II, King of Norway, father of Queen Margaret and son-in-law of King Alexander III.

Claims

In reality only four of these men had genuine claims to the throne: John Hastings, John Balliol, Robert de Brus and Floris V. Of these only Bruce and Balliol had realistic grounds on which to claim the crown. The rest merely wished to have their claims put on the legal record. John Hastings, an Englishman with extensive estates in Scotland, could not succeed to the throne by any of the normal rules governing feudal legacy and instead had his lawyers argue that Scotland was not a true kingdom at all, based, amongst other things, on the fact that Scots kings were traditionally neither crowned noranointed

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or o ...

. As such, by the normal rules of feudal or customary law the kingdom should be split amongst the direct descendants of the co-heiresses of David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ( ...

. Unsurprisingly, a court made up of Scots nobles rejected these arguments out of hand.

John Balliol had the simplest, and thus, by some measure, the strongest claim of the four. By the tradition of primogeniture, he was the rightful claimant (his mother Devorguilla of Galloway having been eldest surviving child of Margaret of Huntingdon, Lady of Galloway, herself the eldest daughter of Earl David of Huntingdon), and that tradition had become steadily entrenched in customary inheritance law both in England and Scotland over the preceding two centuries.Morris, Marc, ''A Great and Terrible King'' (2010), pp.254-258/ref> Balliol also argued that the Kingdom of Scotland was, as royal estate, indivisible as an entity. This was necessary to prevent the kingdom being split equally amongst the heirs as Hastings was suggesting should be done. Robert de Brus (also spelled Bruce), Lord of Annandale, had the best claim to the throne according to

proximity of blood Proximity of blood, or proximity by degree of kinship, is one of the ways to determine hereditary succession based on genealogy. In effect, the application of this rule is a refusal to recognize the right of representation, a component of primogen ...

. As such, his arguments centred on this being a more suitable way to govern the succession than primogeniture. His lawyers suggested that this had been the case in most successions and as such had become something of a 'natural law'. They also put before the court the suggestion that Alexander III had designated Brus as heir when he himself was still childless. Finally, his lawyers argued the concept of primogeniture would only be relevant if customary law applied. Strict customary law, they said, would validate Hastings' argument, and require the kingdom to be split; if the kingdom was indivisible, customary law (including primogeniture) could not apply.Palgrave, F., ''Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland'', 1873 Whatever the rationale for Brus's earlier nomination as heir, however, it was not considered conclusive evidence of which tradition was being followed, because at the time Devorguilla of Galloway had no sons, and so Brus would have also qualified as heir by male-preference primogeniture. As for any apparent contradiction between accepting primogeniture but rejecting partition, Edward I was unsympathetic to the argument, having himself drawn up plans for England to be inherited by his eldest daughter, should he die without sons. In November 1292, therefore, Edward ruled that customary law and primogeniture rather than proximity of blood should be used to determine the rightful heir.

Floris V's argument was that during the reign of William I of Scotland

William the Lion, sometimes styled William I and also known by the nickname Garbh, "the Rough"''Uilleam Garbh''; e.g. Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1214.6; Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1213.10. ( 1142 – 4 December 1214), reigned as King of Scots from 11 ...

the King's brother David, Earl of Huntingdon had resigned the right of himself and his heirs to the throne in exchange for a grant of land in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially different boundaries. The Aberdeenshire Council area incl ...

. If true, this would rule out the first three claimants, all heirs of Earl David, and give Floris the strongest claim to the throne. Floris claimed that although he did not possess copies of the documents detailing the handover of power, one must exist somewhere in Scotland, and Edward postponed the court for a full ten months while a search was made through various castle treasuries. No copy was found at the time, and Floris withdrew his claim in the summer of 1292. In November 1292, following the rejection of Brus's claim, Floris then put forward his claim for a second time—this time with Brus as his backer. There is evidence that he had already entered into an agreement with Brus at the time of withdrawing his claim, in which if one of them was to successfully claim the throne, he would grant the other one third of the kingdom as a feudal fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of f ...

, and Brus may have hoped that pressing Floris's candidacy for a second time might not only put Floris on the throne but give Brus a substantial consolation prize./ref> However, Floris's case was this time rejected for lack of evidence: despite the long interim since his earlier request for an adjournment, he was unable to produce evidence of his claim—due, he claimed, to theft of the vital documents. His claim was this time thrown out for lack of evidence.Morris, Marc, ''A Great and Terrible King'' (2010), p.259

/ref> Copies of the documents he sought would later surface at

Pluscarden

Pluscarden Abbey is a Catholic Benedictine monastery in the glen of the Black Burn, southwest of Elgin, Moray, Scotland. It was founded in 1230 by Alexander II for the Valliscaulian Order.

In 1454, following a merger with the priory of Urqu ...

. One of the early "certified copies", dating the certification seals of the bishop of Moray and the prior of Pluscarden to 1291, is currently located in the Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

. This document is thought to be a forgery.

Finally, in the closing days of the Great Cause, Brus did an about-turn on the matter of the divisibility of the kingdom. He had previously argued that the kingdom was indivisible; now, in view of Edward's ruling that customary law applied, Brus joined his arguments to those of Hastings, and argued that if customary law applied, the kingdom ''was'' divisible after all, and should be divided up between the heirs of Earl David's three daughters. This argument was swiftly rejected, and a verdict given in favour of Balliol as rightful king.

Election

Edward delivered the judgement of the jurors on the Scottish case on 17 November 1292 in favour of John Balliol, with his sonEdward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

becoming heir designate. This decision had the support of the majority of Scots nobles and magnates, even a number of those appointed by Bruce as auditors. Of special note was the support of John II Comyn, another competitor and head of the most powerful baronial family in Scotland, who was married to Balliol's sister, Eleanor. In later years the Comyn family remained staunch supporters of the Balliol claim to the throne.

References