Gray's Inn Square on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four

During the reign of

During the reign of  Many noted barristers, judges and politicians were members of the Inn during this period, including Gilbert Gerard,

Many noted barristers, judges and politicians were members of the Inn during this period, including Gilbert Gerard,

At the start of the

At the start of the  The Caroline period saw a decline in prosperity for Gray's Inn. Although there were many notable members of the Inn, both legal (

The Caroline period saw a decline in prosperity for Gray's Inn. Although there were many notable members of the Inn, both legal (

Gray's Inn does not possess a

Gray's Inn does not possess a

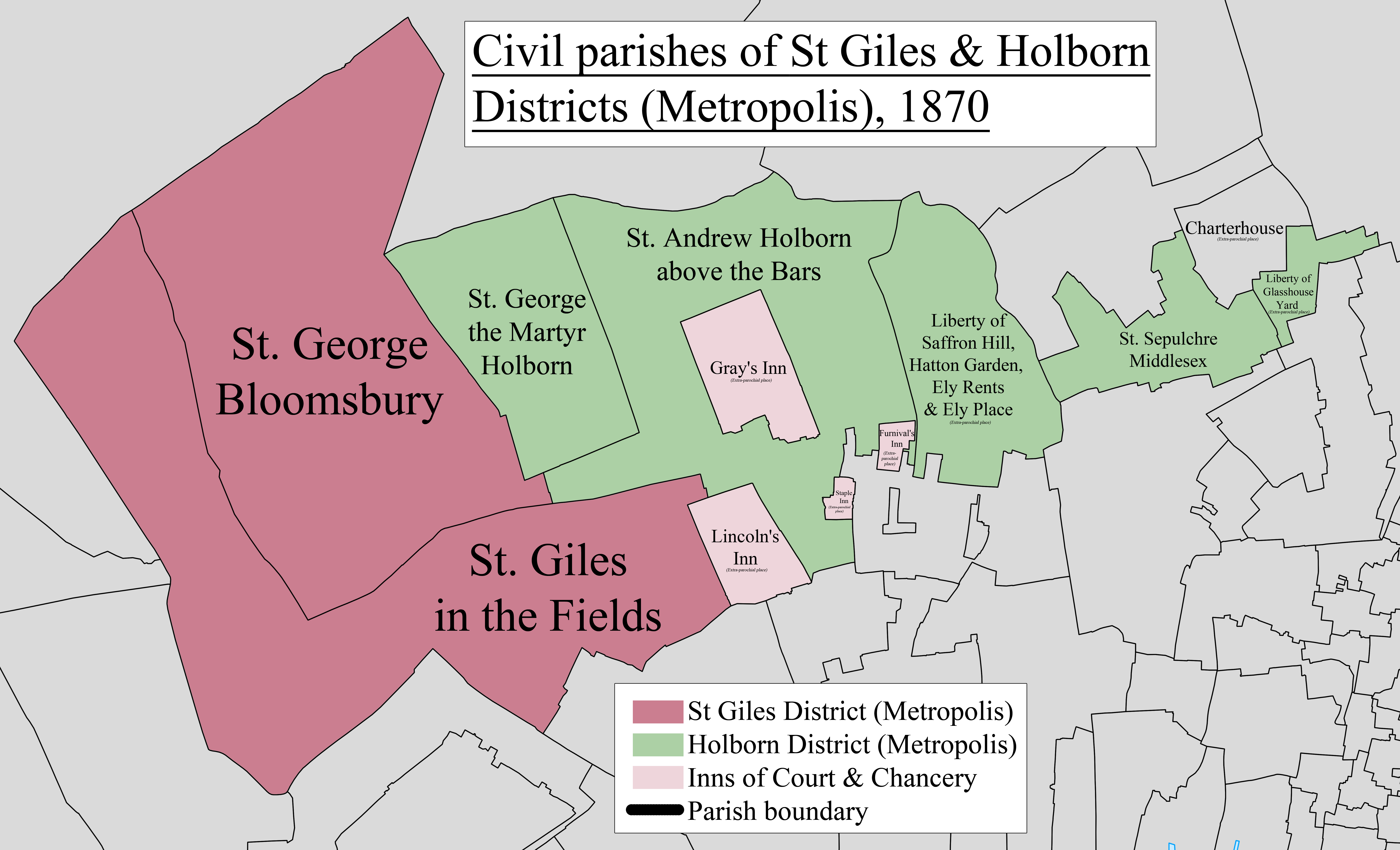

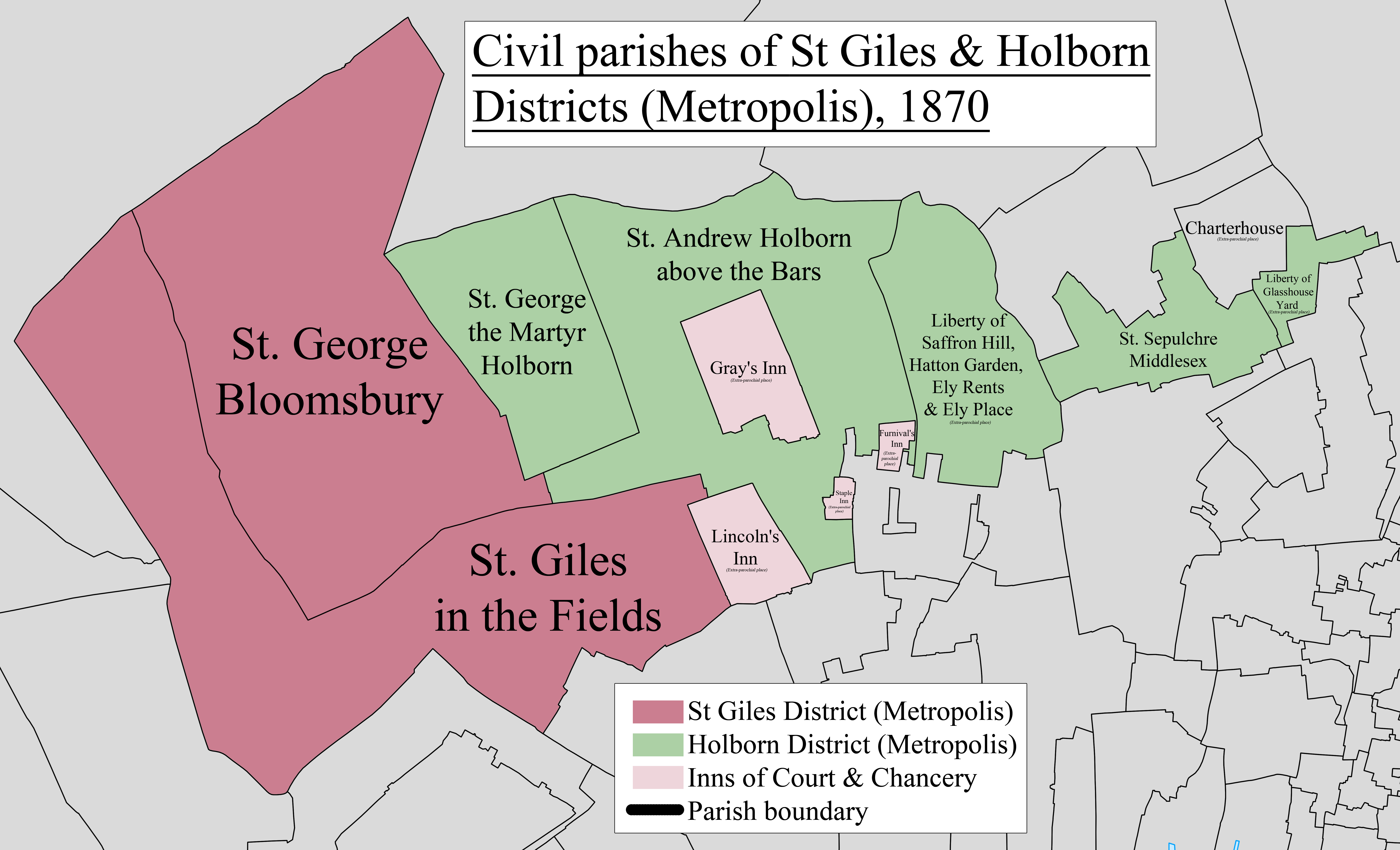

The Inn is located at the intersection of

The Inn is located at the intersection of

The Hall was part of the original Manor of Portpoole, although it was significantly rebuilt during the reign of

The Hall was part of the original Manor of Portpoole, although it was significantly rebuilt during the reign of

The Walks are the gardens within Gray's Inn, and have existed since at least 1597, when records show that

The Walks are the gardens within Gray's Inn, and have existed since at least 1597, when records show that

Banqueting website

{{featured article Bar of England and Wales Buildings and structures in Holborn Buildings and structures in the United Kingdom destroyed during World War II Cricket grounds in Middlesex Cricket in Middlesex Defunct cricket grounds in England Defunct sports venues in London English cricket venues in the 18th century English law Grade I listed buildings in the London Borough of Camden Grade I listed law buildings Grade II* listed parks and gardens in London History of Middlesex Inns of Court Legal buildings in London Middlesex Professional education in London Rebuilt buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Sport in London Sports venues completed in 1730 Sports venues in London

Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court – Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have ...

(professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is ...

, an individual must belong to one of these inns. Located at the intersection of High Holborn

High Holborn ( ) is a street in Holborn and Farringdon Without, Central London, which forms a part of the A40 route from London to Fishguard. It starts in the west at the eastern end of St Giles High Street and runs past the Kingsway and ...

and Gray's Inn Road

Gray's Inn Road (or Grays Inn Road) is an important road in the Bloomsbury district of Central London, in the London Borough of Camden. The road begins at the City of London boundary, where it bisects High Holborn, and ends at King's Cross an ...

in Central London, the Inn is a professional body

A professional association (also called a professional body, professional organization, or professional society) usually seeks to further a particular profession, the interests of individuals and organisations engaged in that profession, and th ...

and provides office and some residential accommodation for barristers. It is ruled by a governing council called "Pension," made up of the Masters of the Bench (or "bencher

A bencher or Master of the Bench is a senior member of an Inn of Court in England and Wales or the Inns of Court in Northern Ireland, or the Honorable Society of King's Inns in Ireland. Benchers hold office for life once elected. A bencher ca ...

s,") and led by the Treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury o ...

, who is elected to serve a one-year term. The Inn is known for its gardens (the “Walks,”) which have existed since at least 1597.

Gray's Inn does not claim a specific foundation date; none of the Inns of Court claims to be any older than the others. Law clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person, generally someone who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial clerks often play significant ...

s and their apprentices have been established on the present site since at latest 1370, with records dating from 1381. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Inn grew in size peaking during the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

. The Inn was home to many important barristers and politicians, including Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

. Queen Elizabeth herself was a patron. As a result of the efforts of prominent members such as William Cecil and Gilbert Gerard, Gray's Inn became the largest of the four Inns by number, with over 200 barristers recorded as members. During this period, the Inn mounted masques and revels. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

’s ''The Comedy of Errors

''The Comedy of Errors'' is one of William Shakespeare's early plays. It is his shortest and one of his most farcical comedies, with a major part of the humour coming from slapstick and mistaken identity, in addition to puns and word play ...

'' is believed first to have been performed in Gray’s Inn Hall.

The Inn continued to prosper during the reign of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

(1603–1625) and the beginning of that of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, when over 100 students per year were recorded as joining. The outbreak of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the A ...

in 1642 during the reign of Charles I disrupted the systems of legal education and governance at the Inns of Court, shutting down all calls to the bar and new admissions, and Gray's Inn never fully recovered. Fortunes continued to decline after the English Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

, which saw the end of the then-traditional method of legal education. Now more prosperous, Gray's Inn is today the smallest of the Inns of Court.

Role

Gray's Inn and the other three Inns of Court remain the only bodies legally allowed tocall

Call or Calls may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Games

* Call, a type of betting in poker

* Call, in the game of contract bridge, a bid, pass, double, or redouble in the bidding stage

Music and dance

* Call (band), from Lahore, Pak ...

a barrister to the Bar, allowing him or her to practise in England and Wales. Although the Inn was previously a disciplinary and teaching body, these functions are now shared between the four Inns, with the Bar Standards Board

The Bar Standards Board regulates barristers in England and Wales for the public interest.

It is responsible for:

* Setting standards of conduct for barristers and authorising barristers to practise;

* Monitoring the service provided by barrist ...

(a division of the General Council of the Bar

The General Council of the Bar, commonly known as the Bar Council, is the representative body for barristers in England and Wales. Established in 1894, the Bar Council is the 'approved regulator' of barristers, but discharges its regulatory functi ...

) acting as a disciplinary body and the Inns of Court and Bar Educational Trust providing education. The Inn remains a collegiate self-governing, unincorporated association of its members, providing within its precincts library, dining, residential and office accommodation (barristers' chambers

In law, a barrister's chambers or barristers' chambers are the rooms used by a barrister or a group of barristers. The singular refers to the use by a sole practitioner whereas the plural refers to a group of barristers who, while acting as s ...

), along with a chapel. Members of the Bar from other Inns may use these facilities to some extent.

History

During the 12th and early 13th centuries, the law was taught in theCity of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

, primarily by the clergy. Then two events happened which ended the Church's role in legal education: firstly, a papal bull that prohibited the clergy from teaching the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

, rather than canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

;Watt (1928) p. 133 and secondly, a decree by Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry as ...

on 2 December 1234 that no institutes of legal education could exist in the City of London. The common law began to be practised and taught by laymen instead of clerics, and these lawyers migrated to the hamlet of Holborn

Holborn ( or ) is a district in central London, which covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon ...

, just outside the City and near to the law courts at Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

.

Founding and early years

The early records of all fourInns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court – Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have ...

have been lost, and it is not known precisely when each was founded. The records of Gray's Inn itself are lost until 1569, and the precise date of founding cannot therefore be verified. Lincoln's Inn has the earliest surviving records. Gray's Inn dates from at least 1370, and takes its name from Baron Grey of Wilton, as the Inn was originally Wilton's family townhouse

A townhouse, townhome, town house, or town home, is a type of terraced housing. A modern townhouse is often one with a small footprint on multiple floors. In a different British usage, the term originally referred to any type of city residence ...

(or inn) within the Manor of Portpoole.Douthwaite (1886) p. 3 A lease was taken for various parts of the inn by practising lawyers as both residential and working accommodation, and their apprentices were housed with them. From this the tradition of dining in "commons", probably by using the inn's main hall, followed as the most convenient arrangement for the members. Outside records from 1437 show that Gray's Inn was occupied by ''socii'', or members of a society, at that date.

In 1456 Reginald de Gray, the owner of the Manor itself, sold the land to a group including Thomas Bryan. A few months later, the other members signed deeds of release, granting the property solely to Thomas Bryan. Bryan acted as either a feoffee

Under the feudal system in England, a feoffee () is a trustee who holds a fief (or "fee"), that is to say an estate in land, for the use of a beneficial owner. The term is more fully stated as a feoffee to uses of the beneficial owner. The use o ...

or an owner representing the governing body of the Inn (there are some records suggesting he may have been a Bencher

A bencher or Master of the Bench is a senior member of an Inn of Court in England and Wales or the Inns of Court in Northern Ireland, or the Honorable Society of King's Inns in Ireland. Benchers hold office for life once elected. A bencher ca ...

at this point) but in 1493 he transferred the ownership by charter to a group including Sir Robert Brudenell and Thomas Wodeward, reverting the ownership of the Inn partially back to the Gray family.

In 1506 the Inn was sold by the Gray family to Hugh Denys

Hugh Denys (c. 14401511) of Osterley in Middlesex, was a courtier of Kings Henry VII and of the young Henry VIII. As Groom of the Stool to Henry VII, he was one of the King's closest courtiers, his role developing into one of administering the P ...

and a group of his feoffees including Roger Lupton

Roger Lupton (1456–27 February 1539/40) was an English lawyer and cleric who served as chaplain to King Henry VII (1485–1509) and to his son King Henry VIII (1509–1547) and was appointed by the former as Provost of Eton College (1503/ ...

. This was not a purchase on behalf of the society and after a five-year delay, it was transferred under the will of Denys in 1516 to the Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has ...

House of Jesus of Bethlehem (Sheen Priory

Sheen Priory (ancient spelling: Shene, Shean, etc.) in Sheen, now Richmond, London, was a Carthusian monastery founded in 1414 within the royal manor of Sheen, on the south bank of the Thames, upstream and approximately 9 miles southwest of th ...

), which remained the Society's landlord until 1539, when the Second Act of Dissolution

The Suppression of Religious Houses Act 1539 (31 Hen 8 c 13), sometimes referred to as the Second Act of Dissolution or as the Act for the Dissolution of the Greater Monasteries, was an Act of the Parliament of England.

It provided for the diss ...

led to the Dissolution of the Monasteries and passed ownership of the Inn to the Crown.

Elizabethan golden age

During the reign of

During the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, Gray's Inn rose in prominence, and the Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female person ...

is considered the "golden age" of the Inn, with Elizabeth serving as the Patron Lady. This can be traced to the actions of Nicholas Bacon, William Cecil and Gilbert Gerard, all prominent members of the Inn and confidantes of Elizabeth. Cecil and Bacon in particular took pains to find the most promising young men and get them to join the Inn. In 1574 it was the largest of all the Inns of Court by number, with 120 barristers, and by 1619 it had a membership of more than 200 barristers.Fletcher (1901) p. xxxii

Gray's Inn, as well as the other Inns of Court, became noted for the parties and festivals it hosted. Students performed masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A mas ...

s and plays in court weddings, in front of Queen Elizabeth herself, and hosted regular festivals and banquets at Candlemas

Candlemas (also spelled Candlemass), also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Feast of the Holy Encounter, is a Christian holiday commemorating the presenta ...

, All Hallows Eve

Halloween or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve) is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints' Day. It begins the observanc ...

and Easter. At Christmas the students ruled the Inn for the day, appointing a Lord of Misrule

In England, the Lord of Misrule – known in Scotland as the Abbot of Unreason and in France as the ''Prince des Sots'' – was an officer appointed by lot during Christmastide to preside over the Feast of Fools. The Lord of Misrul ...

called the ''Prince of Purpoole'', and organising a masque entirely on their own, with the Benchers and other senior members away for the holiday.

The Gray's Inn masque in 1588 with its centrepiece, ''The Misfortunes of Arthur

''The Misfortunes of Arthur, Uther Pendragon's son reduced into tragical notes'' is a play by the 16th-century English dramatist Thomas Hughes. Written in 1587, it was performed at Greenwich before Queen Elizabeth I on February 28, 1588. The play ...

'' by Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes (20 October 182222 March 1896) was an English lawyer, judge, politician and author. He is most famous for his novel '' Tom Brown's School Days'' (1857), a semi-autobiographical work set at Rugby School, which Hughes had attended ...

, is considered by A.W. Ward to be the most impressive masque thrown at any of the Inns. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

performed at the Inn at least once, as his patron, Lord Southampton, was a member. For the Christmas of 1594, his play ''The Comedy of Errors

''The Comedy of Errors'' is one of William Shakespeare's early plays. It is his shortest and one of his most farcical comedies, with a major part of the humour coming from slapstick and mistaken identity, in addition to puns and word play ...

'' was performed by the Lord Chamberlain's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men was a company of actors, or a "playing company" (as it then would likely have been described), for which Shakespeare wrote during most of his career. Richard Burbage played most of the lead roles, including Hamlet, Othel ...

before a riotous assembly of notables in such disorder that the affair became known as the ''Night of Errors'' and a mock trial was held to arraign the culprit. Sadly, after lengthy extensive archival research, there is no concrete evidence that Henry Wriothesley knew or had contact with William Shakspeare from Stratford. If Shake-speare was the pen name for Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron of ...

, who studied at Gray's Inn and was close to Southampton then the performance of the play and the relationship with Henry Wriothesley have a better foundation.

Central to Gray's was the system shared across the Inns of Court of progress towards a call to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call ...

, which lasted approximately 12 to 14 years. A student would first study at either Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the Un ...

or Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, or at one of the Inns of Chancery

The Inns of Chancery or ''Hospida Cancellarie'' were a group of buildings and legal institutions in London initially attached to the Inns of Court and used as offices for the clerks of chancery, from which they drew their name. Existing from a ...

, which were dedicated legal training institutions. If he studied at Oxford or Cambridge he would spend three years working towards a degree, and be admitted to one of the Inns of Court after graduation. If he studied at one of the Inns of Chancery he would do so for one year before seeking admission to the Inn of Court to which his Inn of Chancery was tied—in the case of Gray's Inn, the attached Inns of Chancery were Staple Inn

Staple Inn is a part- Tudor building on the south side of High Holborn street in the City of London, London, England. Located near Chancery Lane tube station, it is used as the London venue for meetings of the Institute and Faculty of Actuar ...

and Barnard's Inn

Barnard's Inn is a former Inn of Chancery in Holborn, London. It is now the home of Gresham College, an institution of higher learning established in 1597 that hosts public lectures.

History

Barnard's Inn dates back at least to the mid-thir ...

.

The student was then considered an "inner barrister", and would study in private, take part in the moots and listen to the readings and other lectures. After serving from six to nine years as an "inner barrister," the student was called to the Bar, assuming he had fulfilled the requirements of having argued twice at moots in one of the Inns of Chancery, twice in the Hall of his Inn of Court and twice in the Inn Library.Fletcher (1901) p. xxxiii The new "utter barrister" was then expected to supervise bolts ("arguments" over a single point of law between students and barristers) and moots at his Inn of Court, attend lectures at the Inns of Court and Chancery and teach students. After five years as an "utter" barrister he was allowed to practice in court—after 10 years he was made an Ancient.

The period saw the establishment of a regular system of legal education. In the early days of the Inn, the quality of legal education had been poor—readings were given infrequently, and the standards for call to the Bar were weak and varied. During the Elizabethan age readings were given regularly, moots took place daily and barristers who were called to the Bar were expected to play a part in teaching students, resulting in skilled and knowledgeable graduates from the Inn.

Many noted barristers, judges and politicians were members of the Inn during this period, including Gilbert Gerard,

Many noted barristers, judges and politicians were members of the Inn during this period, including Gilbert Gerard, Master of the Rolls

The Keeper or Master of the Rolls and Records of the Chancery of England, known as the Master of the Rolls, is the President of the Civil Division of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales and Head of Civil Justice. As a judge, the Master of ...

, Edmund Pelham, Lord Chief Justice of Ireland

The Court of King's Bench (or Court of Queen's Bench during the reign of a Queen) was one of the senior courts of common law in Ireland. It was a mirror of the Court of King's Bench in England. The Lord Chief Justice was the most senior judge ...

, and Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, who served as Treasurer for eight years, supervising significant changes to the facilities of the Inn and the first proper construction of the gardens and walks for which the Inn is noted.

Caroline period and the English Civil War

At the start of the

At the start of the Caroline era

The Caroline era is the period in English and Scottish history named for the 24-year reign of Charles I (1625–1649). The term is derived from ''Carolus'', the Latin for Charles. The Caroline era followed the Jacobean era, the reign of Charles' ...

, when Charles I came to the throne, the Inn continued to prosper. Over 100 students were admitted to the Inn each year, and except during the plague of 1636 the legal education of students continued.Fletcher (1901) p. xliii Masques continued to be held, including one in 1634 organised by all four Inns that cost £21,000—approximately £ in terms. Before 1685 the Inn counted as members five duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, t ...

s, three marquises

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in t ...

, twenty-nine earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form '' jarl'', and meant " chieftain", partic ...

s, five viscounts

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

and thirty-nine barons, and during that period "none can exhibit a more illustrious list of great men".

Many academics, including William Holdsworth, a man considered to be one of the best legal academics in history, maintain that this period saw a decline in the standard of teaching at all the Inns.Aikenhead (1977) p. 249 From 1640 onwards no readings were held, and barristers such as Sir Edward Coke

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only a ...

remarked at the time that the quality of education at the Inns of Court had decreased. Holdsworth put this down to three things—the introduction of printed books, the disinclination of students to attend moots and readings and the disinclination of the Benchers and Readers to enforce attendance.

With the introduction of printing, written legal texts became more available, reducing the need for students to attend readings and lectures. However, this meant that the students denied themselves the opportunity to query what they had learnt or discuss it in greater detail. Eventually, as students now had a way to learn without attending lectures, they began to excuse themselves from lectures, meetings and moots altogether; in the early 17th century they developed a way of deputising other students to do their moots for them. The Benchers and Readers did little to arrest the decline of the practice of lecturers and readings, first because many probably believed (as the students did) that books were an adequate substitute, and secondly because many were keen to avoid the work of preparing a reading, which cut into their time as practising barristers. These problems were endemic to all the Inns, not just Gray's Inn.

The outbreak of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the A ...

led to a complete suspension of legal education, and from November 1642 until July 1644 no Pension meetings were held. Only 43 students were admitted during the four years of the war, and none were called to the Bar. Meetings of Pension resumed after the Battle of Marston Moor

The Battle of Marston Moor was fought on 2 July 1644, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms of 1639 – 1653. The combined forces of the English Parliamentarians under Lord Fairfax and the Earl of Manchester and the Scottish Covenanters u ...

but the education system remained dormant. Although Readers were appointed, none read, and no moots were held. In 1646, after the end of the war, there was an attempt to restore the old system of readings and moots, and in 1647 an order was made that students were required to moot at least once a day. This failed to work, with Readers refusing to read, and the old system of legal education completely died out.

Sir Dudley Digges

Sir Dudley Digges (19 May 1583 – 18 March 1639) was an English diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1610 and 1629. Digges was also a "Virginia adventurer," an investor who ventured his capital in the Virgin ...

, Thomas Bedingfield and Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, for example) and non-legal (including William Juxon

William Juxon (1582 – 4 June 1663) was an English churchman, Bishop of London from 1633 to 1646 and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1660 until his death.

Life

Education

Juxon was the son of Richard Juxon and was born probably in Chichester, ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury), the list could not compare to that of the Elizabethan period.Fletcher (1901) p. lii Following the English Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

, admissions fell to an average of 57 a year.

English Restoration to present

The fortunes of Gray's Inn continued to decline after theEnglish Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

, and by 1719 only 22 students were joining the Inn a year.Fletcher (1910) p. ix This fall in numbers was partly because the landed gentry were no longer sending sons who had no intention of becoming barristers to study at the Inn. In 1615, 13 students joined the Inn for every student called to the Bar, but by 1713 the ratio had become 2.3 new members to every 1 call.

Over a 50-year period, the Civil War and high taxation under William III economically crippled many members of the gentry, meaning that they could not afford to allow their sons to study at the Inns.Fletcher (1910) p. xi David Lemmings considers it to have been more serious than that, for two reasons; firstly, Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and W ...

and Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn ...

had actually shown an increase in membership following the Restoration, and secondly because Gray's Inn had previously had far more "common" members than the other Inns.Lemmings (1990) The decrease in the number of gentry at the Inn could therefore not completely explain the large drop in members.

Gray's Inn was the venue for an early cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

match in July 1730 between London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. The original source reports "a cricket-match between the Kentish men and the Londoners for £50, and won by the former", giving the precise location as "a field near the lower end of Gray's Inn Lane, London".

In 1733 the requirements for a call to the Bar were significantly revised in a joint meeting between the Benchers of Inner Temple and Gray's Inn, revisions accepted by Lincoln's Inn and Middle Temple, although they were not represented. It is not recorded what these changes were, but after a further discussion in 1762 the Inns adopted a rule that any student with a Master of Arts or Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of ...

degree from the universities of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the Un ...

or Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

could be called to the Bar after three years as a student, and any other student could be called after five years.Fletcher (1910) p. xxiv An attempt was made to increase the quality of legal education at Gray's Inn; in 1753 a barrister, Danby Pickering

Danby Pickering ( fl. 1769) was an English legal writer.

Biography

Born circa 1716 (christened 17 March that year),Parish records the son of Danby Pickering of Hatton Garden, Middlesex by his wife Mary (née Horson), Pickering was admitted, on ...

, was employed to lecture there, although this agreement ended in 1761 when he was called to the Bar.

The 18th century was not a particularly prosperous time for the Inn or its members, and few notable barristers were members during this period. Some noted members include Sir Thomas Clarke, the Master of the Rolls

The Keeper or Master of the Rolls and Records of the Chancery of England, known as the Master of the Rolls, is the President of the Civil Division of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales and Head of Civil Justice. As a judge, the Master of ...

, Sir James Eyre, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The chief justice of the Common Pleas was the head of the Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, which was the second-highest common law court in the English legal system until 1875, when it, along with the othe ...

and Samuel Romilly

Sir Samuel Romilly (1 March 1757 – 2 November 1818), was a British lawyer, politician and legal reformer. From a background in the commercial world, he became well-connected, and rose to public office and a prominent position in Parliament. ...

, a noted law reformer. In 1780 the Inn was involved in the case of ''R v the Benchers of Gray's Inn'', a test of the role of the Inns of Court as the sole authority to call students to the Bar. The case was brought to the Court of King's Bench

The King's Bench (), or, during the reign of a female monarch, the Queen's Bench ('), refers to several contemporary and historical courts in some Commonwealth jurisdictions.

* Court of King's Bench (England), a historic court court of common ...

by William Hart, a student at the Inn, who asked the court (under Lord Mansfield

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, PC, SL (2 March 170520 March 1793) was a British barrister, politician and judge noted for his reform of English law. Born to Scottish nobility, he was educated in Perth, Scotland, before moving to L ...

) to order the Inn to call him to the Bar. Mansfield ruled that the Inns of Court were indeed the only organisations able to call students to the Bar, and refused to order the Inns to call Hart.

During the 19th century, the Inns began to stagnate; little had been changed since the 17th century in terms of legal education or practice, except that students were no longer bound to take the Anglican sacrament before their call to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call ...

. In 1852 the Council of Legal Education The Council of Legal Education (CLE) was an English supervisory body established by the four Inns of Court to regulate and improve the legal education of barristers within England and Wales.

History

The Council was established in 1852 by the Inns ...

was established by the Inns, and in 1872 a formal examination for the call to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call ...

was introduced. Gray's Inn itself suffered more than most; as in the 18th century, the fortunes of its members declined, and many barristers who had been called to the Bar at the Inn transferred to others.

Gray's Inn was the smallest of the Inns during the early 20th century, and was noted for its connection to the Northern Circuit

{{Use dmy dates, date=November 2019

The Northern Circuit is a court circuit in England. It dates from 1176 when Henry II sent his judges on circuit to do justice in his name. The Circuit encompassed the whole of the North of England but in 1876 i ...

. During a 1918 Allied World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

conference it would be the site where Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and Winston Churchill, the future leaders of the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy. ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, would first meet. During World War II the Inn was badly damaged during the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

in 1941, with the Hall, the Chapel, the Library and many other buildings hit and almost destroyed. The rebuilding of much of the Inn took until 1960 by the architect Sir Edward Maufe

Sir Edward Brantwood Maufe, RA, FRIBA (12 December 1882 – 12 December 1974) was an English architect and designer. He built private homes as well as commercial and institutional buildings, and is remembered chiefly for his work on place ...

. In 2008 Gray's Inn became the first Inn to appoint "fellows"—elected businesspeople, legal academics and others—with the intent of giving them a wider perspective and education than the other Inns would offer.

Structure and governance

Gray's Inn's internal records date from 1569, at which point there were four types of member; those who had not yet been called to the Bar, Utter Barristers, Ancients and Readers. Utter Barristers were those who had been called to the Bar but were still studying, Ancients were those who were called to the Bar and were allowed to practise and Readers were those who had been called to the Bar, were allowed to practise and now played a part in educating law students at theInns of Chancery

The Inns of Chancery or ''Hospida Cancellarie'' were a group of buildings and legal institutions in London initially attached to the Inns of Court and used as offices for the clerks of chancery, from which they drew their name. Existing from a ...

and at Gray's Inn itself. At the time Gray's Inn was the odd one out amongst the Inns; the others did not recognise Ancients as a degree of barrister and had Benchers roughly corresponding to the Readers used at Gray's Inn (although the positions were not identical).Simpson (1973) p. 135

The Inn is run by Pension, its ultimate governing body. The name is peculiar to Gray's Inn—at Lincoln's Inn the governing body is called the Council, and at the Inner and Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn ...

s it is called the Parliament. The name was used for the governing bodies of three of the Inns of Chancery—Barnard's Inn

Barnard's Inn is a former Inn of Chancery in Holborn, London. It is now the home of Gresham College, an institution of higher learning established in 1597 that hosts public lectures.

History

Barnard's Inn dates back at least to the mid-thir ...

, Clement's Inn and New Inn

New Inn - ( cy, Y Dafarn Newydd) - is a village and community directly south east of Pontypool, within the County Borough of Torfaen in Wales, within the historic boundaries of Monmouthshire. It had a population of 5,986 at the 2011 Census.

...

. In Gray's Inn the Readers, when they existed, were required to attend Pension meetings, and other barristers were at one point welcome to, although only the Readers would be allowed to speak. Pension at Gray's Inn is made up of the Masters of the Bench, and the Inn as a whole is headed by the Treasurer, a senior Bencher. The Treasurer has always been elected, and since 1744 the office has rotated between individuals, with a term of one year.

Readers

A Reader was a person literally elected to read—he would be elected to the Pension (council) of Gray's Inn, and would take his place by giving a "reading", or lecture, on a particular legal topic. Two readers would be elected annually by Pension to serve a one-year term. Initially (before the rise of the Benchers) the Readers were the governing body of Gray's Inn, and formed Pension. The earliest certain records of Readers are from the 16th century—although the Inn's records only start at 1569William Dugdale

Sir William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) was an English antiquary and herald. As a scholar he was influential in the development of medieval history as an academic subject.

Life

Dugdale was born at Shustoke, near Cole ...

(himself a member) published a list in his ''Origines Juridiciales'' dating from 1514. S.E. Thorne published a list dating from 1430, but this is entirely conjectural and not based on any official records, only reports of "readings" that took place at Gray's Inn. By 1569 there had certainly been Readers for more than a century.Simpson (1973) p. 138

The English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of Kingdom of England, England's governanc ...

marked the end of legal education at the Inns, and the class of Readers went into decline. The last Readers were appointed in 1677, and the position of the Readers as heads of the Inn and members of Pension was taken by the Benchers.

Benchers

A Bencher, Benchsitter or (formally) Master of the Bench, is a member of Pension, the governing body of the Honourable Society of Gray's Inn. The term originally referred to one who sat on the benches in the main hall of the Inn which were used for dining and during moots, and the term originally had no significance.Simpson (1973) p. 139 The position of Bencher developed during the 16th century when the Readers, for unknown reasons, decided that some barristers who were not Readers should be afforded the same rights and privileges as those who were, although without a voice in Pension. This was a rare practice and occurred a total of seven times within the 16th century, the first being Robert Flynt in 1549. The next was Nicholas Bacon in 1550, thenEdward Stanhope

Edward Stanhope PC (24 September 1840 – 21 December 1893) was a British Conservative Party politician who was Secretary of State for War from 1887 to 1892.

Background and education

Born in London, Stanhope was the second son of Philip Stan ...

in 1580, who was afforded the privilege because, although a skilled attorney, an illness meant he could never fulfil the duties of a Reader.Simpson (1973) p. 140

The practice became more common during the 17th century—11 people were made Benchers between 1600 and 1630—and in 1614 one of the Benchers appointed was explicitly allowed to be a member of Pension.Simpson (1973) p. 141 This became more common, creating a two-rank system in which both Readers and Benchers were members of Pension. However far more Readers were appointed than Benchers—50 between 1600 and 1630—and it appeared that Readers would remain the higher rank despite this change.

The outbreak of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the A ...

in 1642 marked the end of legal education at the Inns, although Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

attempted to persuade Readers to continue by threatening them with fines. The class of Readers went into decline and Benchers were called as members of Pension instead. In 1679 there was the first mass-call of Benchers (22 on one occasion, and 15 on another), with the Benchers paying a fine of 100 marks because they refused to read, and modern Benchers pay a "fine" in a continuation of this tradition.Simpson (1973) p. 142

Noted Benchers of Gray's Inn include Lord Birkenhead and Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

. Honorary Benchers can also be appointed, although they have no role in Pension, such as Lord Denning

Alfred Thompson "Tom" Denning, Baron Denning (23 January 1899 – 5 March 1999) was an English lawyer and judge. He was called to the bar of England and Wales in 1923 and became a King's Counsel in 1938. Denning became a judge in 1944 whe ...

, who was appointed in 1979, and Winston Churchill. Today there are over 300 Benchers in Gray's Inn, mostly senior barristers and members of the judiciary.

Badge

Gray's Inn does not possess a

Gray's Inn does not possess a coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in it ...

''per se'' but instead uses a heraldic badge

A heraldic badge, emblem, impresa, device, or personal device worn as a badge indicates allegiance to, or the property of, an individual, family or corporate body. Medieval forms are usually called a livery badge, and also a cognizance. They are ...

, which is often displayed on a shield. It is blazon

In heraldry and heraldic vexillology, a blazon is a formal description of a coat of arms, flag or similar emblem, from which the reader can reconstruct the appropriate image. The verb ''to blazon'' means to create such a description. The visua ...

ed either " Azure an Indian Griffin proper

Proper may refer to:

Mathematics

* Proper map, in topology, a property of continuous function between topological spaces, if inverse images of compact subsets are compact

* Proper morphism, in algebraic geometry, an analogue of a proper map for ...

segreant" or, more currently, "Sable

The sable (''Martes zibellina'') is a species of marten, a small omnivorous mammal primarily inhabiting the forest environments of Russia, from the Ural Mountains throughout Siberia, and northern Mongolia. Its habitat also borders eastern Kaz ...

a griffin segreant or", i.e., a gold griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late Latin, Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail ...

on a black background. The Inn originally used a variant of the coat of arms of the Grey family, but this was changed to the griffin at some time around the 1590s. There is no record of why this was done, but it is possible that the new emblem was adapted from the arms of the Treasurer Richard Aungier (d. 1597).

The Inn's motto, the date of adoption of which is unknown, is ''Integra Lex Aequi Custos Rectique Magistra Non Habet Affectus Sed Causas Gubernat'', which is Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

for 'Impartial justice, guardian of equity, mistress of the law, without fear or favour rules men's causes aright'. The seal of Gray's Inn consists of the badge encircled by the motto.

Buildings and gardens

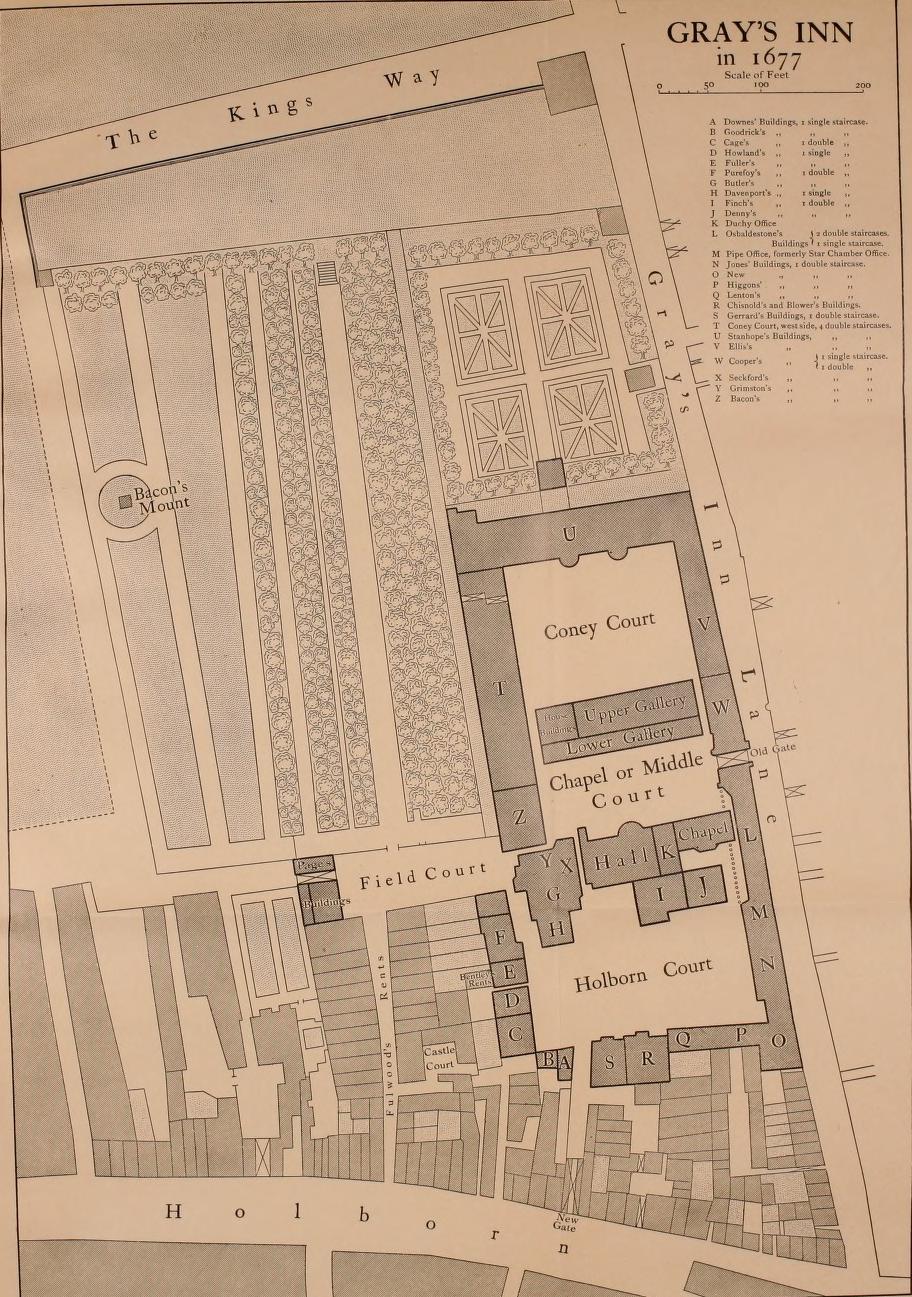

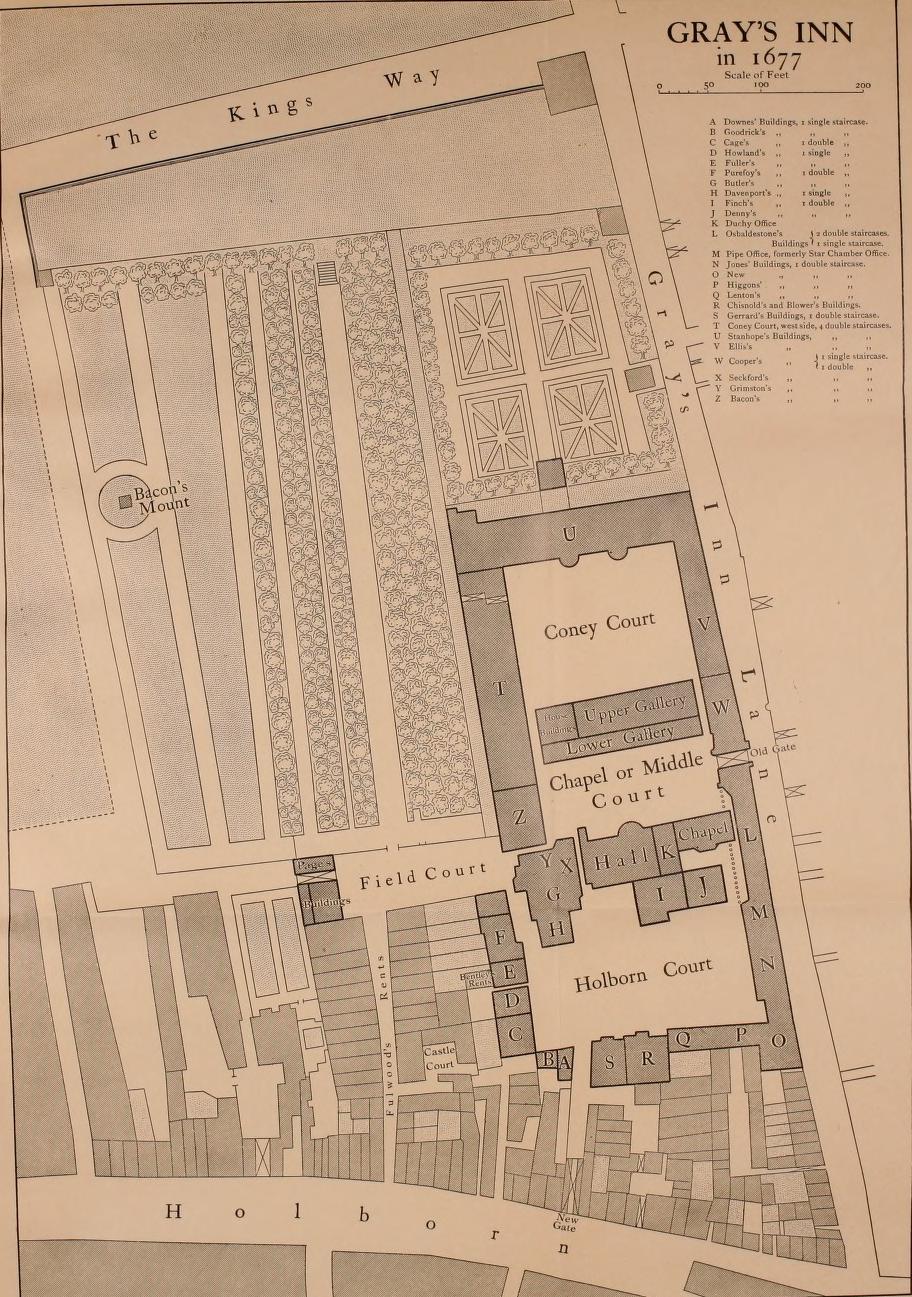

The Inn is located at the intersection of

The Inn is located at the intersection of High Holborn

High Holborn ( ) is a street in Holborn and Farringdon Without, Central London, which forms a part of the A40 route from London to Fishguard. It starts in the west at the eastern end of St Giles High Street and runs past the Kingsway and ...

and Gray's Inn Road

Gray's Inn Road (or Grays Inn Road) is an important road in the Bloomsbury district of Central London, in the London Borough of Camden. The road begins at the City of London boundary, where it bisects High Holborn, and ends at King's Cross an ...

. It started as a single manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals with ...

with a hall and chapel, although an additional wing had been added by the date of the "Woodcut" map of London, drawn probably in the early 1560s. Expansion continued over the following decades, and by 1586 the Pension had added another two wings around the central court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to Adjudication, adjudicate legal disputes between Party (law), parties and carry out the administration of justice in Civil law (common law), civil, C ...

. Around these were several sets of barristers' chambers

In law, a barrister's chambers or barristers' chambers are the rooms used by a barrister or a group of barristers. The singular refers to the use by a sole practitioner whereas the plural refers to a group of barristers who, while acting as s ...

erected by members of the Inn under a leasehold

A leasehold estate is an ownership of a temporary right to hold land or property in which a lessee or a tenant holds rights of real property by some form of title from a lessor or landlord. Although a tenant does hold rights to real property, a l ...

agreement whereby ownership of the buildings would revert to the Inn at the end of the lease.

As the Inn grew it became necessary (for safety purposes) to wall off the land owned by the Inn, which had previously been open to everyone. In 1591 the "back field" was walled off, but little more was done until 1608, when under the supervision of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, the Treasurer, more construction work was undertaken, particularly in walling off and improving the gardens and walks. In 1629 it was ordered that an architect supervise any construction and ensure that the new buildings were architecturally similar to the old ones, and the strict enforcement of this rule during the 18th century is given as a reason for the uniformity of the buildings at Gray's Inn.

During the late 17th century many buildings were demolished, either because of poor repair or to standardise and modernise the buildings at the Inn. Many more were built over the open land surrounding the Inn, although this was controversial at the time; in November 1672 the Privy Council and Charles II himself were petitioned to order that nothing should be built on the open land, and a similar request was sent to the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. T ...

in May 1673. From 1672 to 1674 additional buildings were constructed in the Red Lyon Fields by Nicholas Barebone, and members of the Inn attempted to sue him to prevent this. After the lawsuits failed members of the Inn were seen to fight with Barebones' workmen, "wherein several were shrewdly hurt".Fletcher (1910) p. xii

In February 1679 a fire broke out on the west side of Coney Court, necessitating the rebuilding of the entire row. Another fire broke out in January 1684 in Coney Court, destroying several buildings including the Library. A third fire in 1687 destroyed a large part of Holborn Court, and when the buildings were rebuilt after these fires they were constructed of brick to be more resistant to fire than the wood and plaster previously used in construction. As a result, the domestic Tudor style architecture

The Tudor architectural style is the final development of Medieval architecture in England and Wales, during the Tudor period (1485–1603) and even beyond, and also the tentative introduction of Renaissance architecture to Britain. It ...

which had dominated much of the Inn was replaced with more modern styles.Fletcher (1910) p. xiv Records show that prior to the rebuilding in 1687, the Inn had been "so incommodious" that the "ancients" were forced to work two to a chamber. More of the Inn was rebuilt during that period, and between 1669 and 1774 all of the Inn apart from parts of the Hall and Chapel had been rebuilt.

More buildings were constructed during the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1941 the Inn suffered under The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

, which damaged or destroyed much of the Inn, necessitating the repair of many buildings and the construction of more. Today many buildings are let as professional offices for barristers and solicitors with between and of office space available. There are also approximately 60 residential apartments, rented out to barristers who are members of the Inn. The Inn also contains the Inns of Court School of Law

The City Law School is one of the five schools of City, University of London. In 2001, the Inns of Court School of Law became part of City, and is now known as the City Law School. Until 1997, the ICSL had a monopoly on the provision of the Bar ...

, a joint educational venture between all four Inns of Court where the vocational training for barristers and solicitors is undertaken. The current Inn layout consists of two squares—South Square and Gray's Inn Square—with the remaining buildings arranged around the Walks.

Hall

The Hall was part of the original Manor of Portpoole, although it was significantly rebuilt during the reign of

The Hall was part of the original Manor of Portpoole, although it was significantly rebuilt during the reign of Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

, and again during the reign of Elizabeth, with the rebuilding being finished on 10 November 1559. The rebuilt Hall measured in length, in width and in height, and remains about the same size today. It has a hammerbeam roof

A hammerbeam roof is a decorative, open timber roof truss typical of English Gothic architecture and has been called "...the most spectacular endeavour of the English Medieval carpenter". They are traditionally timber framed, using short beams pr ...

and a raised dais at one end with a grand table on it, where the Benchers and other notables would originally have sat.

The hall also contains a large carved screen at one end covering the entrance to the Vestibule

Vestibule or Vestibulum can have the following meanings, each primarily based upon a common origin, from early 17th century French, derived from Latin ''vestibulum, -i n.'' "entrance court".

Anatomy

In general, vestibule is a small space or cavity ...

. Legend says that the screen was given to the Inn by Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

while she was the Inn's patron, and is carved out of the wood of a Spanish galleon captured from the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an a ...

. The Hall was lit with the aid of massive windows filled with the Coats of Arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in it ...

of those members who became Treasurers.Douthwaite (1886) p. 113 The Benchers' table is also said to have been a gift from Elizabeth, and as a result the only public toast in the Inn until the late 19th century was "to the glorious, pious and immortal memory of Queen Elizabeth".

The walls of the Hall are decorated with paintings of noted patrons or members of the Inn, including Nicholas Bacon and Elizabeth I.Douthwaite (1886) p. 141 During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

the Hall was one of those buildings badly damaged during the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

. The Treasurers' Arms and paintings had been moved to a place of safety and were not damaged; during the rebuilding after the War they were put back in the Hall, where they remain. The rebuilt hall was designed by Edward Maufe, and was formally opened in 1951 by the Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester () is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curre ...

.

Chapel

The Chapel existed in the original manor house used by the Inn,Fletcher (1901) p. xxxv and dates from 1315. In 1625 it was enlarged under the supervision of Eubule Thelwall, but by 1698 it was "very ruinous", and had to be rebuilt. Little is known of the changes, except that thebarristers' chambers

In law, a barrister's chambers or barristers' chambers are the rooms used by a barrister or a group of barristers. The singular refers to the use by a sole practitioner whereas the plural refers to a group of barristers who, while acting as s ...

above the Chapel were removed.Fletcher (1910) p. xv The building was again rebuilt in 1893, and remained that way until its destruction during The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

in 1941. The Chapel was finally rebuilt in 1960, and the original stained glass windows (which had been removed and taken to a safe location) were restored. The rebuilt Chapel contains "simple furnishings" made of Canadian maple

''Acer'' () is a genus of trees and shrubs commonly known as maples. The genus is placed in the family Sapindaceae.Stevens, P. F. (2001 onwards). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 9, June 2008 nd more or less continuously updated since ht ...

donated by the Canadian Bar Association

The Canadian Bar Association (CBA), or Association du barreau canadien (ABC) in French, represents over 37,000 lawyers, judges, notaries, law teachers and law students from across Canada.

History

The Association's first Annual Meeting was he ...

.

The Inn has had a Chaplain since at least 1400, where a court case is recorded as being brought by the "Chaplain of Greyes Inn". During the 16th century the Inn began hiring full-time preachers to staff the Chapel—the first, John Cherke, was appointed in 1576. A radical Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

in a time of religious conflict, Cherke held his post for only a short time before being replaced by a Thomas Crooke in 1580.Foster (1889) p. 499 After Crooke's death in 1598 Roger Fenton served as preacher, until his replacement by Richard Sibbes

Richard Sibbes (or Sibbs) (1577–1635) was an Anglican theologian. He is known as a Biblical exegete, and as a representative, with William Perkins and John Preston, of what has been called "main-line" Puritanism because he always remained in ...

, later Master of Catherine Hall, Cambridge, in 1616. Gray's Inn still employs a Preacher; Michael Doe, former Bishop of Swindon

The Bishop of Swindon is an episcopal title used by a suffragan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Bristol, in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title takes its name after the town of Swindon in Wiltshire. The title of Bishop of Mal ...

and more recently General Secretary of the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel

United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG) is a United Kingdom-based charitable organization (registered charity no. 234518).

It was first incorporated under Royal Charter in 1701 as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Part ...

, was appointed in 2011.

Walks

The Walks are the gardens within Gray's Inn, and have existed since at least 1597, when records show that

The Walks are the gardens within Gray's Inn, and have existed since at least 1597, when records show that Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

was to be paid £7 for "planting of trees in the walkes". Prior to this the area (known as Green Court) was used as a place to dump waste and rubble, since at the time the Inn was open to any Londoner. In 1587 four Benchers were ordered by the Pension to "consider what charge a brick wall in the fields will draw unto And where the said wall shalbe fittest to be builded", and work on such a wall was completed in 1598, which helped keep out the citizens of London.

In 1599 additional trees were planted in the Walks, and stairs up to the Walks were also added. When Francis Bacon became treasurer in 1608 more improvements were made, since he no longer had to seek the approval of the Pension to make changes. In September 1608 a gate was installed on the southern wall, and various gardeners were employed to maintain the Walks. The gardens became commonly used as a place of relaxation, and James Howell

James Howell (c. 1594 – 1666) was a 17th-century Anglo-Welsh historian and writer who is in many ways a representative figure of his age. The son of a Welsh clergyman, he was for much of his life in the shadow of his elder brother Thomas Ho ...

wrote in 1621 that "I hold ray's Inn Walksto be the pleasantest place about London, and that there you have the choicest society".

The Walks were well-maintained during the reign of William III, although the Inn's lack of prosperity made more improvements impossible. In 1711 the gardener was ordered not to admit "any women or children into the Walkes", and in 1718 was given permission to physically remove those he found. At the end of the 18th century Charles Lamb said that the Walks were "the best gardens of any of the Inns of Court, their aspect being altogether reverend and law-abiding". In 1720 the old gate was replaced by "a pair of handsome iron gates with peers and other proper imbellishments". The 19th and 20th centuries saw few major changes, apart from the introduction of plane trees

''Platanus'' is a genus consisting of a small number of tree species native to the Northern Hemisphere. They are the sole living members of the family Platanaceae.

All mature members of ''Platanus'' are tall, reaching in height. All except ...

into the Walks.

The Walks are listed Grade II* on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens

The Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England provides a listing and classification system for historic parks and gardens similar to that used for listed buildings. The register is managed by Historic England ...

.

Library

The Library of Gray's Inn has existed since at least 1555, when the first mention of it was made in the will of Robert Chaloner, who left some money to buy law books for the Library. The Library was neither a big collection nor a dedicated one; in 1568 it was being housed in a single room in the chambers of Nicholas Bacon, a room that was also used formooting

Moot court is a co-curricular activity at many law schools. Participants take part in simulated court or arbitration proceedings, usually involving drafting memorials or memoranda and participating in oral argument. In most countries, the phrase ...

and to store the deed

In common law, a deed is any legal instrument in writing which passes, affirms or confirms an interest, right, or property and that is signed, attested, delivered, and in some jurisdictions, sealed. It is commonly associated with transferrin ...

chest. The collection grew larger over the years as individual Benchers such as Sir John Finch and Sir John Bankes

Sir John Bankes (1589 – 28 December 1644) was an English lawyer and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1624 and 1629. He was Attorney General and Chief Justice to Charles I during the English Civil War. Corfe Castle, his famil ...

left books or money to buy books in their wills, and the first Librarian was appointed in 1646 after members of the Inn had been found stealing books.

In 1669 books were bought by the Inn as an organisation for the first time, and a proper catalogue was drawn up to prevent theft. In 1684 a fire that broke out in Coney Court, where the Library was situated, and destroyed much of the collection. While some books were saved, most of the records prior to 1684 were lost. A "handsome room" was then built to house the Library.

The Library became more important during the 18th century; prior to that it had been a small, little-used collection of books. In 1725 it was proposed by the Pension that "a publick Library be sett up and kept open for ye use of ye society",Fletcher (1910) p. xxvi and that more books be purchased. The first order of new books was on 27 June 1729 and consisted of "a collection of Lord Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both n ...

's works". In 1750 the Under-Steward of the Inn made a new catalogue of the books, and in 1789 the Library was moved to a new room between the Hall and the Chapel.Fletcher (1910) p. xxvii In 1840 another two rooms were erected in which to store books, and in 1883 a new Library was constructed with space to store approximately 11,000 books. This was rapidly found to be inadequate, and in 1929 a new Library, known as the Holker Library after the benefactor, Sir John Holker

Sir John Holker (1828 – 24 May 1882) was a British lawyer, politician, and judge. He sat as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament for Preston (UK Parliament constituency), Preston from 1872 until his death ten ye ...

, was opened. The library, although impressive looking, was not particularly useful. Francis Cowper wrote that:

Though impressive to look at, the new building was something less than a success as a library. The air of spaciousness was produced at the expense of shelf room, and though in the octagonThe building did not last very long—damage to the Inn duringt the north end T, or t, is the twentieth Letter (alphabet), letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is English alphabe ...the decorative effect of row upon row of books soaring upwards towards the cornice was considerable, the loftiest were totally inaccessible save to those who could scale the longest and dizziest ladders. Further, the appointments were of such surpassing magnificence that no ink-pots were allowed in the room for fear of accidents.Ruda (2008) p. 111

the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

completely destroyed the Library and a large part of its collection, although the rare manuscripts, which had been moved elsewhere, survived. After the destruction of much of the Inn's collection, George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

donated replacements for many lost texts. A prefabricated building in the Walks was used to hold the surviving books while a new Library was constructed, and the new building (designed by Sir Edward Maufe

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only ...

) was opened in 1958. It is similar in size to the old Holker Library, but is more workmanlike and designed to allow for easy access to the books.

Notable members

Having existed for over 600 years, Gray's Inn has a long list of notable members and honorary members. Names of many members can be found in theList of members of Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known simply as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these Inns. Th ...

. Even as the smallest of the Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court – Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have ...

it has had members who have been particularly noted lawyers and judges, such as Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, The 1st Earl of Birkenhead, Baron Slynn, Lord Bingham of Cornhill

Sir Thomas Henry Bingham, Baron Bingham of Cornhill, (13 October 193311 September 2010), was an eminent British judge who was successively Master of the Rolls, Lord Chief Justice and Senior Law Lord. He was described as the greatest lawyer ...

, Lord Hoffmann

Leonard Hubert "Lennie" Hoffmann, Baron Hoffmann (born 8 May 1934) is a retired senior South African–British judge. He served as a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary from 1995 to 2009.

Well known for his lively decisions and willingness to break ...

and Baroness Hale of Richmond

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...