Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich of Russia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Konstantin Pavlovich (russian: Константи́н Па́влович; ) was a

The direction of the boy's upbringing was entirely in the hands of his grandmother, the empress

The direction of the boy's upbringing was entirely in the hands of his grandmother, the empress

During this time, Konstantin's first campaign took place under the leadership of Suvorov. The battle of Bassignana was lost by Konstantin's fault; but at Novi he distinguished himself by personal bravery, so that the emperor Paul bestowed on him the title of

During this time, Konstantin's first campaign took place under the leadership of Suvorov. The battle of Bassignana was lost by Konstantin's fault; but at Novi he distinguished himself by personal bravery, so that the emperor Paul bestowed on him the title of

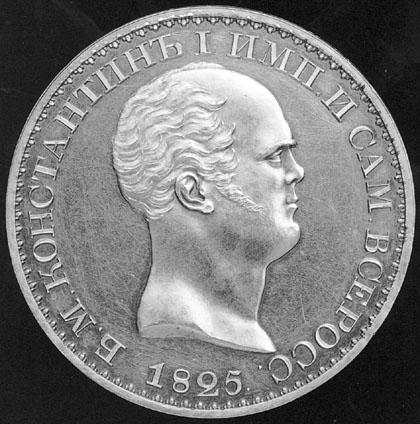

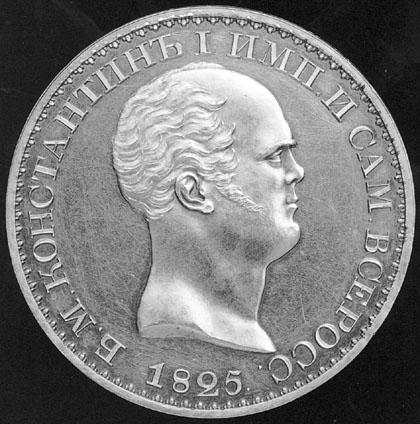

When Alexander I died on 1 December 1825, Grand Duke Nicholas had Konstantin proclaimed emperor in Saint Petersburg. In Warsaw meanwhile, Konstantin abdicated the throne. When that became public knowledge, the Northern Society scrambled in secret meetings to convince regimental leaders not to swear allegiance to Nicholas. The efforts would culminate in the

When Alexander I died on 1 December 1825, Grand Duke Nicholas had Konstantin proclaimed emperor in Saint Petersburg. In Warsaw meanwhile, Konstantin abdicated the throne. When that became public knowledge, the Northern Society scrambled in secret meetings to convince regimental leaders not to swear allegiance to Nicholas. The efforts would culminate in the

grand duke

Grand duke (feminine: grand duchess) is a European hereditary title, used either by certain monarchs or by members of certain monarchs' families. In status, a grand duke traditionally ranks in order of precedence below an emperor, as an approxi ...

of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and the second son of Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Paul I Paul I may refer to:

*Paul of Samosata (200–275), Bishop of Antioch

*Paul I of Constantinople (died c. 350), Archbishop of Constantinople

*Pope Paul I (700–767)

*Paul I Šubić of Bribir (c. 1245–1312), Ban of Croatia and Lord of Bosnia

*Paul ...

and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg

Sophie is a version of the female given name Sophia, meaning "wise".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Sophie of Thuringia, Duchess of ...

. He was the heir-presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of an heir apparent or a new heir presumptive with a better claim to the position in question.

...

for most of his elder brother Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

's reign, but had secretly renounced his claim to the throne in 1823. For 25 days after the death of Alexander I, from 19 November (O.S.)/1 December 1825 to 14 December (O.S.)/26 December 1825 he was known as ''His Imperial Majesty Konstantin I Emperor and Sovereign of Russia'', although he never reigned and never acceded to the throne. His younger brother Nicholas

Nicholas is a male given name and a surname.

The Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Anglicanism, Anglican Churches celebrate Saint Nicholas every year on December 6, which is the name day for "Nicholas". In Greece, the n ...

became Tsar in 1825. The succession controversy became the pretext of the Decembrist revolt

The Decembrist Revolt ( ru , Восстание декабристов, translit = Vosstaniye dekabristov , translation = Uprising of the Decembrists) took place in Russia on , during the interregnum following the sudden death of Emperor Al ...

.

Konstantin was known to eschew court etiquette

Etiquette () is the set of norms of personal behaviour in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviours that accord with the conventions and norms observed and practised by a ...

and to take frequent stands against the wishes of his brother Alexander I, for which he is remembered fondly in Russia, but in his capacity as the governor of Poland he is remembered as a hated ruler.

Early life

Konstantin was born inTsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the cen ...

on 27 April 1779, the second son of the Tsesarevich Paul Petrovich and his wife Maria Fyodorovna, daughter of Friedrich II Eugen, Duke of Württemberg

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

. Of all Paul's children, Konstantin most closely resembled his father both physically and mentally.

His paternal grandmother Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

named him after Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

, the founder of the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. A medal with antique figures was struck to commemorate his birth; it bears the inscription "Back to Byzantium" which clearly alludes to Catherine's Greek Plan

The Greek Plan or Greek Project () was an early solution to the Eastern Question which was advanced by Catherine the Great in the early 1780s. It envisaged the partition of the Ottoman Empire between the Russian and Habsburg Empires followed ...

. According to the British ambassador James Harris,

The direction of the boy's upbringing was entirely in the hands of his grandmother, the empress

The direction of the boy's upbringing was entirely in the hands of his grandmother, the empress Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

. As in the case of her eldest grandson (afterwards the emperor Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

), she regulated every detail of his physical and mental education; but in accordance with her usual custom, she left the carrying out of her views to the men who were in her confidence. Count Nikolai Saltykov

Count, then Prince Nikolay Ivanovich Saltykov (russian: Николай Иванович Салтыков, 31 October 1736 – 28 May 1816), a member of the Saltykov noble family, was a Russian Imperial Field Marshal and courtier best known ...

was supposed to be the actual tutor, but he too in his turn transferred the burden to another, interfering personally only on exceptional occasions, and exercised no influence upon the character of the passionate, restless and headstrong boy. The only person who exerted a responsible influence was Cesar La Harpe, who was tutor-in-chief from 1783 to May 1795 and educated both the empress's grandsons.

Catherine arranged Konstantin's marriage as she had Alexander's; Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

Princess Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (Coburg, 23 September 1781 – Elfenau, near Bern, Switzerland, 12 August 1860), also known as Grand Duchess Anna Feodorovna of Russia (russian: Анна Фёдоровна), was a German princess of the d ...

, 14, and Konstantin, 16, were married on 26 February 1796. As Caroline Bauer

Caroline Bauer (29 March 1807 – 18 October 1877) was a German actress of the Biedermeier era who used the name Lina Bauer.

Biography

Caroline Philippina Augusta Bauer (german: Karoline Philippine Auguste Bauer) was born in Heidelberg, Ger ...

recorded in her memoirs, "The brutal Constantine treated his consort like a slave. So far did he forget all good manners and decency that, in the presence of his rough officers, he made demands on her, as his property, which will hardly bear being hinted of." Due to his violent treatment and suffering health problems as a result, Juliane separated from Konstantin in 1799; she eventually settled in Switzerland. An attempt by Konstantin in 1814 to convince her to return broke down in the face of her firm opposition.

Napoleonic Wars

During this time, Konstantin's first campaign took place under the leadership of Suvorov. The battle of Bassignana was lost by Konstantin's fault; but at Novi he distinguished himself by personal bravery, so that the emperor Paul bestowed on him the title of

During this time, Konstantin's first campaign took place under the leadership of Suvorov. The battle of Bassignana was lost by Konstantin's fault; but at Novi he distinguished himself by personal bravery, so that the emperor Paul bestowed on him the title of tsesarevich

Tsesarevich (russian: Цесаревич, ) was the title of the heir apparent or presumptive in the Russian Empire. It either preceded or replaced the given name and patronymic.

Usage

It is often confused with " tsarevich", which is a di ...

, which according to the fundamental law of the constitution belonged only to the heir to the throne. Though it cannot be proved that this action of the tsar denoted any far-reaching plan, it yet shows that Paul already distrusted the grand-duke Alexander.

Konstantin never tried to secure the throne. After his father's death in 1801, he led a disorderly bachelor life. He abstained from politics, but remained faithful to his military inclinations, without manifesting anything more than a preference for the externalities of the service. In command of the Imperial Guards during the campaign of 1805, he had a share of the responsibility for the Russian defeat at the battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz in ...

; while in 1807 neither his skill nor his fortune in war showed any improvement.

After the peace of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when t ...

he became an ardent admirer of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and an upholder of the Russo-French alliance. He therefore lost the confidence of his brother Alexander; to the latter, the French alliance was merely a means to an end. This view was not held by Konstantin; even in 1812, after the fall of Moscow, he pressed for a speedy conclusion of peace with Napoleon, and, like field marshal Kutuzov

Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov ( rus, Князь Михаи́л Илларио́нович Голени́щев-Куту́зов, Knyaz' Mikhaíl Illariónovich Goleníshchev-Kutúzov; german: Mikhail Illarion Golenishchev-Kut ...

, he too opposed the policy which carried the war across the Russian frontier to victorious conclusion upon French soil. His personal behaviour towards both his own men and French prisoners was eccentric and cruel.

During the campaign, Barclay de Tolly

Barclay de Tolly () is the name of a Baltic German noble family of Scottish origin (Clan Barclay). During the time of the Revolution of 1688 in Britain, the family migrated to Swedish Livonia from Towy (Towie) in Aberdeenshire. Its subsequen ...

was twice obliged to send him away from the army due to his disorderly conduct. His share in the battles in Germany and France was insignificant. At Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

, on 26 August, his military knowledge failed him at the decisive moment, but at La Fère-Champenoise he distinguished himself by personal bravery. In Paris the grand duke excited public ridicule by the manifestation of his petty military fads. His first visit was to the stables, and it was said that he had been marching and drilling even in his private rooms.

Governor of the Kingdom of Poland

Konstantin's importance in political history dates from when his brother, Tsar Alexander, installed him inCongress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

as ''de facto'' viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

(however, he was not the "official viceroy", namestnik of the Kingdom of Poland The Namiestnik (or Viceroy) of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, namiestnik Królestwa Polskiego, russian: наместник Царства Польского) was the deputy of the Emperor of Russia who, under Congress Poland (1815–1874), styled himse ...

), with a task of the militarization and discipline of Poland. In Congress Poland, he received the post of commander-in-chief of the forces of the kingdom to which was added in 1819 the command of the Lithuanian troops and of those of the Russian provinces that had belonged to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

(so called Western Krai

Western Krai (russian: Западный край, literally ''Western Land'') was an unofficial name for the westernmost parts of the Russian Empire, excluding the territory of Congress Poland (which was sometimes referred to as Vistula Krai). Th ...

).

Alexander's policies were liberal by the standards of Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

Europe. Classical liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, economic ...

s lapped up the freedoms of education, scholarship and economic development, but key deficiencies in Poland's autonomy like lack of control over the budget, military, and trade left them hungry for more. The Kalisz Opposition, led by the brothers Bonawentura and Wincenty Niemojowski, pressed for reforms including more independence for the judiciary. Alexander, calling their actions an "abuse" of liberty, suspended the Polish parliament (Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

) for five years and authorised Konstantin to maintain order in the kingdom by any means necessary.

Konstantin, attempting to execute his brother's mandate to silence dissent, strengthened the secret police (Ochrana

The Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order (russian: Отделение по охранению общественной безопасности и порядка), usually called Guard Department ( rus, Охранное отд ...

) and suppressed the Polish patriotic movements, leading to further popular discontent. Konstantin also harassed the liberal opposition, replaced Poles with Russians on important posts in local administration and the army and often insulted and assaulted his subordinates, which led to conflicts in the officer corps

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent contex ...

. The Sejm, until then mostly dominated by supporters of the personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with Russia, saw his actions as disobedience of the very constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

of which he felt personally proud. That also led to him being mocked, which he did not help by sending his adjutants with threats to those "guilty" of it like Wirydianna Fiszerowa

Wirydianna Fiszerowa (born Wirydianna Radolińska, using the Leszczyc coat of arms, later Wirydianna Kwilecka) (1761 in Wyszyny - 1826 in Działyń) was a Polish noblewoman best known for her memoirs, which mention her life in pre- and post-pa ...

. Nevertheless, Konstantin was an ardent supporter of Polish musicians, such as Maria Agata Szymanowska

Maria Szymanowska (Polish pronunciation: ; born Marianna Agata Wołowska; Warsaw, 14 December 1789 – 25 July 1831, St. Petersburg, Russia) was a Polish composer and one of the first professional virtuoso pianists of the 19th century. She tour ...

and Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period, who wrote primarily for solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown as a leadin ...

.

After 19 years of separation, the marriage of Konstantin and Juliane was formally annulled on 20 March 1820. Two months later, on 27 May, Konstantin married the Polish Countess Joanna Grudzińska

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility.L. G. Pine, Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty'' ...

, who was given the title of ''Her Serenity Princess of Lowicz.'' Connected with that, he renounced any claim to the Russian succession, which was formally completed in 1822. After the marriage, he became increasingly attached to his new home of Poland.

Succession crisis and Decembrist Uprising

When Alexander I died on 1 December 1825, Grand Duke Nicholas had Konstantin proclaimed emperor in Saint Petersburg. In Warsaw meanwhile, Konstantin abdicated the throne. When that became public knowledge, the Northern Society scrambled in secret meetings to convince regimental leaders not to swear allegiance to Nicholas. The efforts would culminate in the

When Alexander I died on 1 December 1825, Grand Duke Nicholas had Konstantin proclaimed emperor in Saint Petersburg. In Warsaw meanwhile, Konstantin abdicated the throne. When that became public knowledge, the Northern Society scrambled in secret meetings to convince regimental leaders not to swear allegiance to Nicholas. The efforts would culminate in the Decembrist revolt

The Decembrist Revolt ( ru , Восстание декабристов, translit = Vosstaniye dekabristov , translation = Uprising of the Decembrists) took place in Russia on , during the interregnum following the sudden death of Emperor Al ...

.

Under Nicholas I, Konstantin maintained his position in Poland. Differences soon arose between him and his brother because of the part taken by the Poles in the Decembrist conspiracy. Konstantin hindered the unveiling of the organized plotting for independence, which had been going on in Poland for many years, and held obstinately to the belief that the army and the bureaucracy were loyally devoted to the Russian Empire. The eastern policy of the Tsar and the Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

in 1828 to 1829 caused a fresh breach between them. The opposition of Konstantin made the Polish army take no part in the war.

Failed assassination and November uprising

An assassination attempt was made on the life of Grand Duke Konstantin, which precipitated the November 1830 insurrection in Warsaw (theNovember Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in W ...

). After the attempt on Konstantin’s life, a secret court was set up to prosecute those who were responsible. "It was learned that Nicholas had ordered the Grand Duke Konstantin ... to start an energetic investigation and court-martial the culprits ... the committee at its session of 27 November decided irrevocably to start the revolution on the evening of the 29th, at 6pm." Like the assassination, the recruitment of army units by the rebels failed; only two units joined them, and only the capture of the armory and the subsequent arming of the populace kept the revolt alive. Konstantin saw the revolt as a strictly Polish affair and refused to use troops, as he could have, because it was foolish politically. He could trust his Russian troops, but to use them might be considered a violation of the kingdom's independence and even an act of war.

Because of that setback, he was limited to the resources around him. If he decided to intervene, it would require a different source of manpower. He was limited to the handful of Polish troops he could gather together. Constantin thus refused to send his troops against the revolutionaries: "The Poles have started this disturbance, and it's Poles that must stop it", and he left the suppression of the revolt in the hands of the Polish government.

Polish Prince Ksawery Lubecki, realizing that the insurgents had formed no government by midnight, assembled some members of the council and other prominent personalities on his own initiative. They sent a delegation to the grand duke, but when he stated again that he did not wish to intervene in any way, the committees decided to take matters into their own hands. Konstantin’s involvement remained minimal, showing considerable restraint in not wanting to use Russian troops to help put down the rebellion. The timid response that he did give was that he would not attack the city of Warsaw without giving it 48 hours' notice, that he would intercede between the emperor and the Polish Kingdom, and would not order Lithuanian troops to enter Poland. What he was trying to accomplish was to remain neutral at all costs, which led to a belief among his fellow Russians that he was more sensitive towards the Polish independence than to Russian dominance. The securing of neutrality from Konstantin gave the Polish government the feeling that Russia would not attack Poland and gave it the chance effectively to quash the uprising.

After ensuring Russian neutrality, Konstantin retreated behind Russian lines. That further confused the Polish government regarding its status with Russia because of a previous Russian promise to help put down the rebellion. The patriotic Poles could not have been more pleased. Konstantin, on 3 December, retreated toward Russia. Following the failure of the uprising, Konstantin expressed admiration for the valor of the Polish insurgents. The policy of neutrality at all costs has led to Konstantin being viewed two ways through the scope of history. Either he would be viewed by the Russian royal family as weak and sympathetic to the Poles, or he would be seen as a seed for the idea of a soon to be independent Poland, but he was effectively only trying to avoid a wider war.

Death and legacy

Konstantin died ofcholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

in Vitebsk

Vitebsk or Viciebsk (russian: Витебск, ; be, Ві́цебск, ; , ''Vitebsk'', lt, Vitebskas, pl, Witebsk), is a city in Belarus. The capital of the Vitebsk Region, it has 366,299 inhabitants, making it the country's fourth-largest ci ...

(now in Belarus) on 27 June 1831 and did not live to see the suppression of the revolution. His frequent stands against the wishes of the Imperial Family were perceived in Russia as brave, even gallant. In Poland, he was viewed as a tyrant, hated by the military and civilian population alike, and in Polish literature

Polish literature is the literary tradition of Poland. Most Polish literature has been written in the Polish language, though other languages used in Poland over the centuries have also contributed to Polish literary traditions, including Latin, ...

, Konstantin is portrayed as a cruel despot.

Archives

Konstantin's letters to his grandfather,Frederick II Eugene, Duke of Württemberg

Friedrich Eugen, Duke of Württemberg (21 January 1732 – 23 December 1797) was the fourth son of Karl Alexander, Duke of Württemberg, and Princess Maria Augusta of Thurn and Taxis (11 August 1706 – 1 February 1756). He was born in Stuttg ...

, (together with letters from his siblings) written between 1795 and 1797, are preserved in the State Archive of Stuttgart (Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart) in Stuttgart, Germany.

Honours

Ancestry

Citations

References

*Further reading

* * Karnovich's ''The Cesarevich Constantine Pavlovich'' (2 vols., St Petersburg, 1899). * {{DEFAULTSORT:Konstantin Pavlovich Of Russia, Grand Duke 1779 births 1831 deaths People from Pushkin, Saint Petersburg People from Tsarskoselsky Uyezd 19th-century Russian monarchs 19th-century Polish monarchs House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov Russian grand dukes Pretenders to the Russian throne Russian commanders of the Napoleonic Wars Cavalry commanders 18th-century people from the Russian Empire Deaths from cholera Infectious disease deaths in Russia Tsesarevichs of Russia Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 1st class Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 1st class Recipients of the Order of St. George of the Second Degree Grand Crosses of the Military Order of Maria Theresa Grand Crosses of the Military Order of Max Joseph Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of William Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Children of Paul I of Russia Sons of emperors Burials at Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg