Graeco-Arabic translation movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Graeco-Arabic translation movement was a large, well-funded, and sustained effort responsible for translating a significant volume of secular Greek texts into Arabic. The translation movement took place in

The Abbasid revolution and the move to a new capital in Baghdad introduced the ruling administration to a new set of demographic populations more influenced by Hellenism. At the same time, the ruling elite of the new dynasty strove to adopt a Sassanian Imperial Ideology, which itself was also influenced by Greek thought. These factors culminated in a capital more receptive to and actively interested in the knowledge contained in scientific manuscripts of Classical Greece. The translation movement played a significant role in the

The Abbasid revolution and the move to a new capital in Baghdad introduced the ruling administration to a new set of demographic populations more influenced by Hellenism. At the same time, the ruling elite of the new dynasty strove to adopt a Sassanian Imperial Ideology, which itself was also influenced by Greek thought. These factors culminated in a capital more receptive to and actively interested in the knowledge contained in scientific manuscripts of Classical Greece. The translation movement played a significant role in the

Historically, the House of Wisdom is a story of many successes. In 750 AD, the Abbasid's overthrew the Ummayad Caliphate, becoming the ruling power in the Islamic world. In 762 AD, Abu Jaʿfar Abdallah ibn Muhammad al-Mansur, the second Abbasid Caliph, decided to move the capital of the empire to his newly built city of Baghdad in Iraq from Damascus, which was in Syria. Al-Mansur was very cognizant of the need to cultivate intellect and wanted to advance and magnify the status of the Islamic people and their culture. As a result, he established a library, the House of Wisdom, in Baghdad where scholars and students could study new material, formulate new ideas, transcribe literature of their own, and translate various works from around the world into the Arabic language. Al-Mansur's descendants were also active in the cultivation of intellect, especially in the area of translation. Under the rule of Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid (better known as al-Maʿmun) the House of Wisdom thrived, acquiring a large amount of support and recognition. Al-Maʿmun would send scholars all over the civilized world to retrieve various scientific and literary works to be translated. The head translator at the time, Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi, who was a Christian Arab of al-Hira, is believed to have translated over one hundred books, including the work ''On Anatomy of the Veins and Arteries'' by Galen. Due to the translation movement under al-Maʿmun, the House of Wisdom was one of the largest repositories of scientific and literary books in the world at the time and remained that way until the Siege of Baghdad in 1258 AD. The destruction and pillaging of Baghdad by the Mongols also included the destruction of the House of Wisdom, however, the books and other works inside were taken to Maragha by Hulagu Khan and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.

Historically, the House of Wisdom is a story of many successes. In 750 AD, the Abbasid's overthrew the Ummayad Caliphate, becoming the ruling power in the Islamic world. In 762 AD, Abu Jaʿfar Abdallah ibn Muhammad al-Mansur, the second Abbasid Caliph, decided to move the capital of the empire to his newly built city of Baghdad in Iraq from Damascus, which was in Syria. Al-Mansur was very cognizant of the need to cultivate intellect and wanted to advance and magnify the status of the Islamic people and their culture. As a result, he established a library, the House of Wisdom, in Baghdad where scholars and students could study new material, formulate new ideas, transcribe literature of their own, and translate various works from around the world into the Arabic language. Al-Mansur's descendants were also active in the cultivation of intellect, especially in the area of translation. Under the rule of Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid (better known as al-Maʿmun) the House of Wisdom thrived, acquiring a large amount of support and recognition. Al-Maʿmun would send scholars all over the civilized world to retrieve various scientific and literary works to be translated. The head translator at the time, Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi, who was a Christian Arab of al-Hira, is believed to have translated over one hundred books, including the work ''On Anatomy of the Veins and Arteries'' by Galen. Due to the translation movement under al-Maʿmun, the House of Wisdom was one of the largest repositories of scientific and literary books in the world at the time and remained that way until the Siege of Baghdad in 1258 AD. The destruction and pillaging of Baghdad by the Mongols also included the destruction of the House of Wisdom, however, the books and other works inside were taken to Maragha by Hulagu Khan and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.

Abu Zaid Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi was a profound

Abu Zaid Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi was a profound

Greek Thought, Arabic Culture. The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early 'Abbasaid Society (2nd-4th 5th-10th centuries)

'. Routledge.

in which the

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

from the mid-eighth century to the late tenth century.

While the movement translated from many languages into Arabic, including Pahlavi, Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominalization, nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cul ...

, Syriac Syriac may refer to:

* Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages ...

, and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, it is often referred to as the Graeco-Arabic translation movement because it was predominantly focused on translating the works of Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

scholars and other secular Greek texts into Arabic.

Pre-Abbasid developments

Pre-Islamic developments

The ninth king of the Sasanian Empire,Shapur II

Shapur II ( pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 ; New Persian: , ''Šāpur'', 309 – 379), also known as Shapur the Great, was the tenth Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran. The List of longest-reigning monarchs, longest ...

, established the Academy of Gondishapur

The Academy of Gondishapur ( fa, فرهنگستان گندیشاپور, Farhangestân-e Gondišâpur), also known as the Gondishapur University (دانشگاه گندیشاپور Dânešgâh-e Gondišapur), was one of the three Sasanian ...

, which was to be a medical center, a library, as well as a college where various subjects like anatomy, theology, medicine, and philosophy would be studied. Later, Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

established an observatory that could offer studies in dentistry, architecture, agriculture and irrigation, basics of commanding in military, astronomy, and mathematics. The Academy of Gondishapur was then considered as the greatest crucial center of medicine during the sixth as well as the seventh century. However, during the seventh century CE, the Sasanian Empire was conquered by the Muslim armies, but they preserved the center.

Further west, the Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as l ...

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

closed the Academy of Athens in 529 CE. Along with the defunding of key public educational institutions, many scholars fled the region with their knowledge and materials. These migrant scholars sought asylum in Persia, whose ruler actively ensured their safe passage out of Byzantium and supported their academic ambitions.

Early Islamic Empire and Umayyad Period (632–750 CE)

Although Greek to Arabic translations were common during the Umayyad Period due to large Greek-speaking populations residing in the empire, the translation of Greek scientific texts was scarce. The Graeco-Arabic translation movement began, in earnest, at the beginning of theAbbasid Period

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

. However, many events and conditions during the rise of the Islamic empire helped to shape the setting and circumstances in which the movement blossomed. The Arab conquests before and during the Umayyad Period that spread into Southwest Asia, Persia, and Northeast Africa laid the groundwork for a civilization capable of fueling the Graeco-Arabic translation movement. These conquests united a massive area under the Islamic State, connecting societies and peoples previously isolated, invigorating trade routes and agriculture, and improving material wealth among subjects. The newfound regional stability under the Umayyad dynasty likely fostered higher literacy rates and a larger educational infrastructure. Syriac-speaking Christians and other Hellenistic Christian communities in Iraq and Iran were assimilated into the structure of the empire. These Hellenized peoples were crucial in supporting a growing institutional interest in secular Greek learning.

Abbasid Period (750–1258 CE)

The Abbasid revolution and the move to a new capital in Baghdad introduced the ruling administration to a new set of demographic populations more influenced by Hellenism. At the same time, the ruling elite of the new dynasty strove to adopt a Sassanian Imperial Ideology, which itself was also influenced by Greek thought. These factors culminated in a capital more receptive to and actively interested in the knowledge contained in scientific manuscripts of Classical Greece. The translation movement played a significant role in the

The Abbasid revolution and the move to a new capital in Baghdad introduced the ruling administration to a new set of demographic populations more influenced by Hellenism. At the same time, the ruling elite of the new dynasty strove to adopt a Sassanian Imperial Ideology, which itself was also influenced by Greek thought. These factors culminated in a capital more receptive to and actively interested in the knowledge contained in scientific manuscripts of Classical Greece. The translation movement played a significant role in the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

.

The advent and rapid spread of papermaking

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a speciali ...

learned from Chinese prisoners of war in 751 CE also helped to make the translation movement possible.

The translation movement in Arab progressed in development during the Abbasid period. During the 8th century, there was still no tradition of translating Greek works into Arabic. However, Christian scholars had been translating medical, philosophical, and other Greek works into the Syriac language for centuries. For this reason, the beginning of the translation movement involved the caliphs commissioning Christian scholars who had already established their own translation infrastructure to begin translating various Greek works into the Arabic tongue via Syriac intermediates. For example, one letter by the Patriarch Timothy I Timothy I may refer to:

* Pope Timothy I of Alexandria, Pope of Alexandria & Patriarch of the See of St. Mark in 378–384

* Timothy I of Constantinople, Patriarch of Constantinople in 511–518

* Timothy I (Nestorian patriarch), Catholicus-Patria ...

described how he himself had been commissioned to perform one of these translations of Aristotle. A famous example of one of these translators was the Christian Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (also Hunain or Hunein) ( ar, أبو زيد حنين بن إسحاق العبادي; (809–873) was an influential Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic ...

. In later periods, Muslim scholars built off of this infrastructure and gained the capacity to begin perform these translations themselves directly from the Greek originals and into Arabic.

The Abbasid period encompassed one of the very critical markers in the movement's history, that is, the translation of the central texts of the Islamic religion, in this case, the Quran. The translation movement in the Arab World was greatly supported under the Islamic rule, and led to the translation of materials to Arabic from different languages like middle Persian. The translation movement was instigated by the Barmakids

The Barmakids ( fa, برمکیان ''Barmakiyân''; ar, البرامكة ''al-Barāmikah''Harold Bailey, 1943. "Iranica" BSOAS 11: p. 2. India - Department of Archaeology, and V. S. Mirashi (ed.), ''Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era'' vol ...

. Available documents depict that Persian texts were greatly privileged by the translation movement.

The movement succeeded in forming civilization overlap and initiated new maps in the fields of culture and politics. Islamic rulers participated in the movement in numerous ways, for example, creating classes for translation to facilitate its flow all through the various phases of the Islamic empire

This article includes a list of successive Islamic states and Muslim dynasties beginning with the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) and the early Muslim conquests that spread Islam outside of the Arabian Peninsula, and continu ...

s. The translation movement had a significant effect on developing the scientific knowledge of the Arabs since several theories in science had surfaced from various origins. Late, there was the introduction of the western culture to the Arabic translations that were preserved since most of their initial scripts could not be located.

One of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

's contemporaries, an Arab doctor named Harith b. Kalada, is said to have studied in the medical academy at Gondeshapur, however this story is likely legendary. When Muhammad died in 632 CE, caliphs that were considered Rightly Guided Caliphs were chosen to lead the Empire of Islam, the information of the Quran was becoming more known in the surrounding civilizations. There was an expansion of the Islamic empire, leading to searching of multilingual teachers as well as people to translate and teach the Quran and the Arabic language. Later, the Quran would be incorporated into one language.

A polyglot who was considered to be fluent in almost all the targeted languages was regarded as among the greatest translators during that time. He majored in the medical field. Through a hand from his son, Ishaq Hunayn, as well as his nephew, Habash, he translated more than ninety-five pieces of Galen, almost fifteen pieces of Hippocrates, about the soul, and about generation as well as corruption. The Arabic language extensively expanded to reach communities in places such as Morocco and Andalusia and would later be adapted as their language that was regarded as official. The Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

caliphs greatly helped in translating science as well as arts, which gave out a long-term foundation for the Empire of Islam. While Islam expanded, there was the preservation of other cultures by the Muslims and the utilization of technology and their knowledge of science in the efforts of stimulating their language to develop.

The

House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, بيت الحكمة, Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

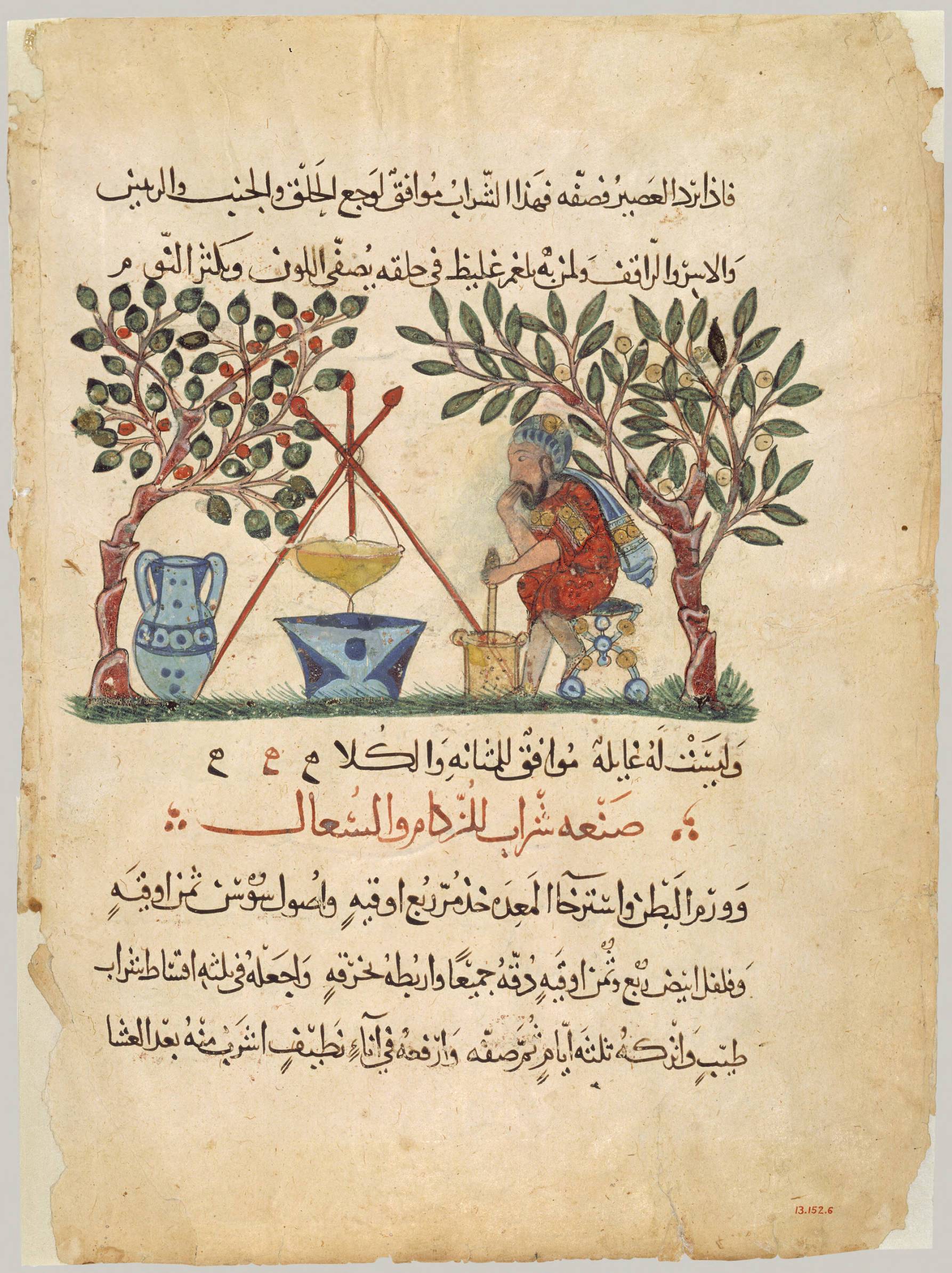

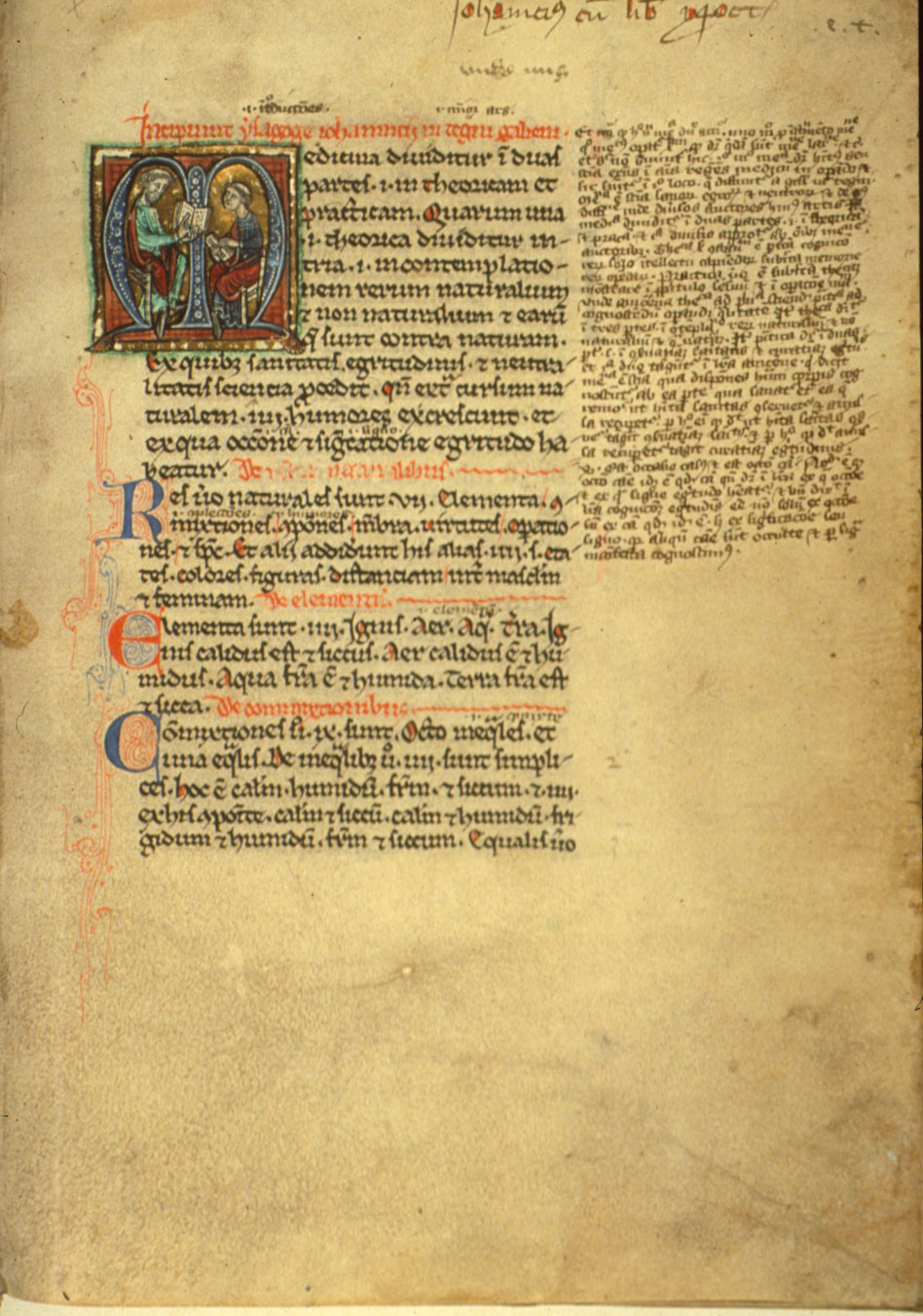

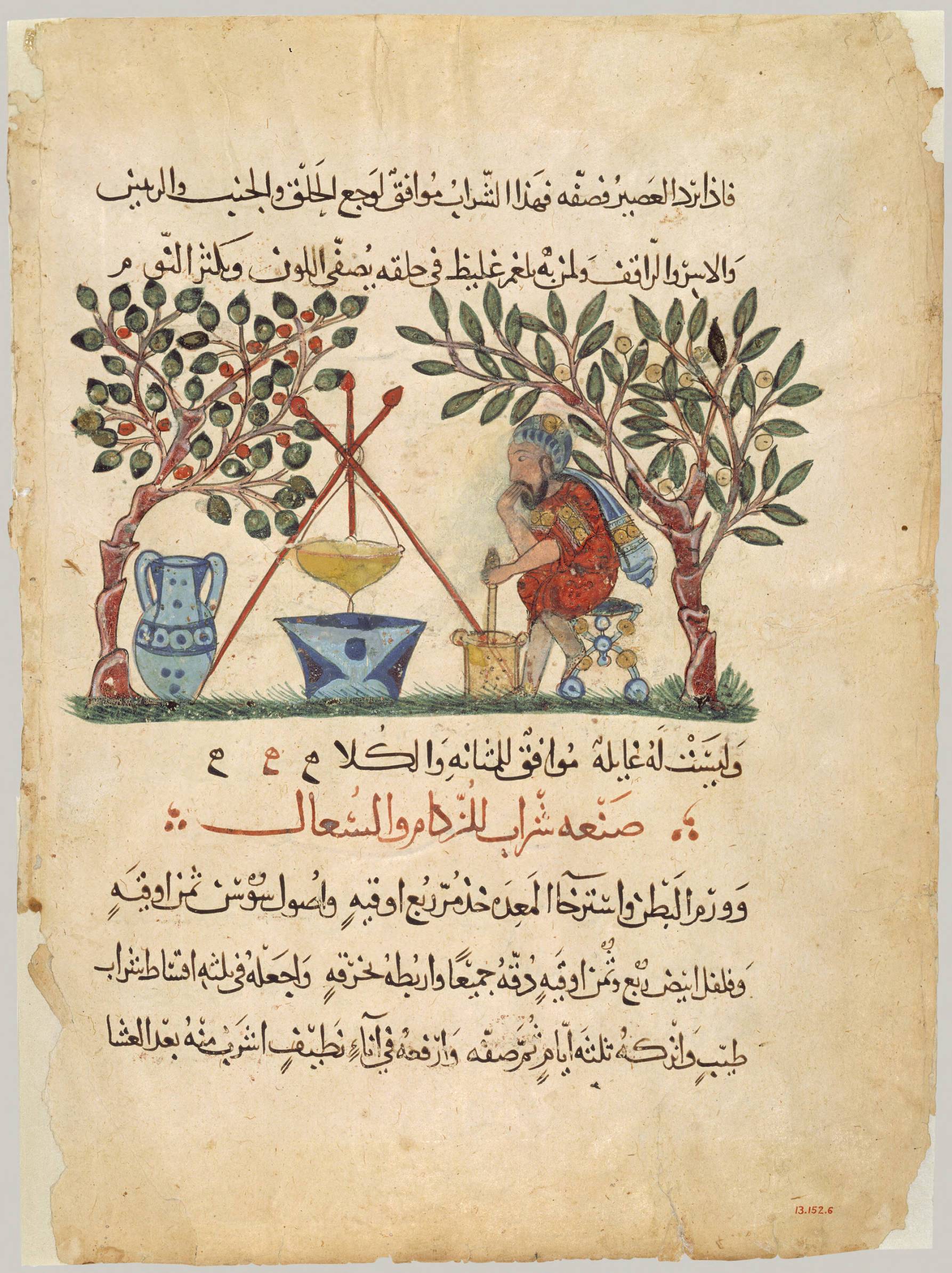

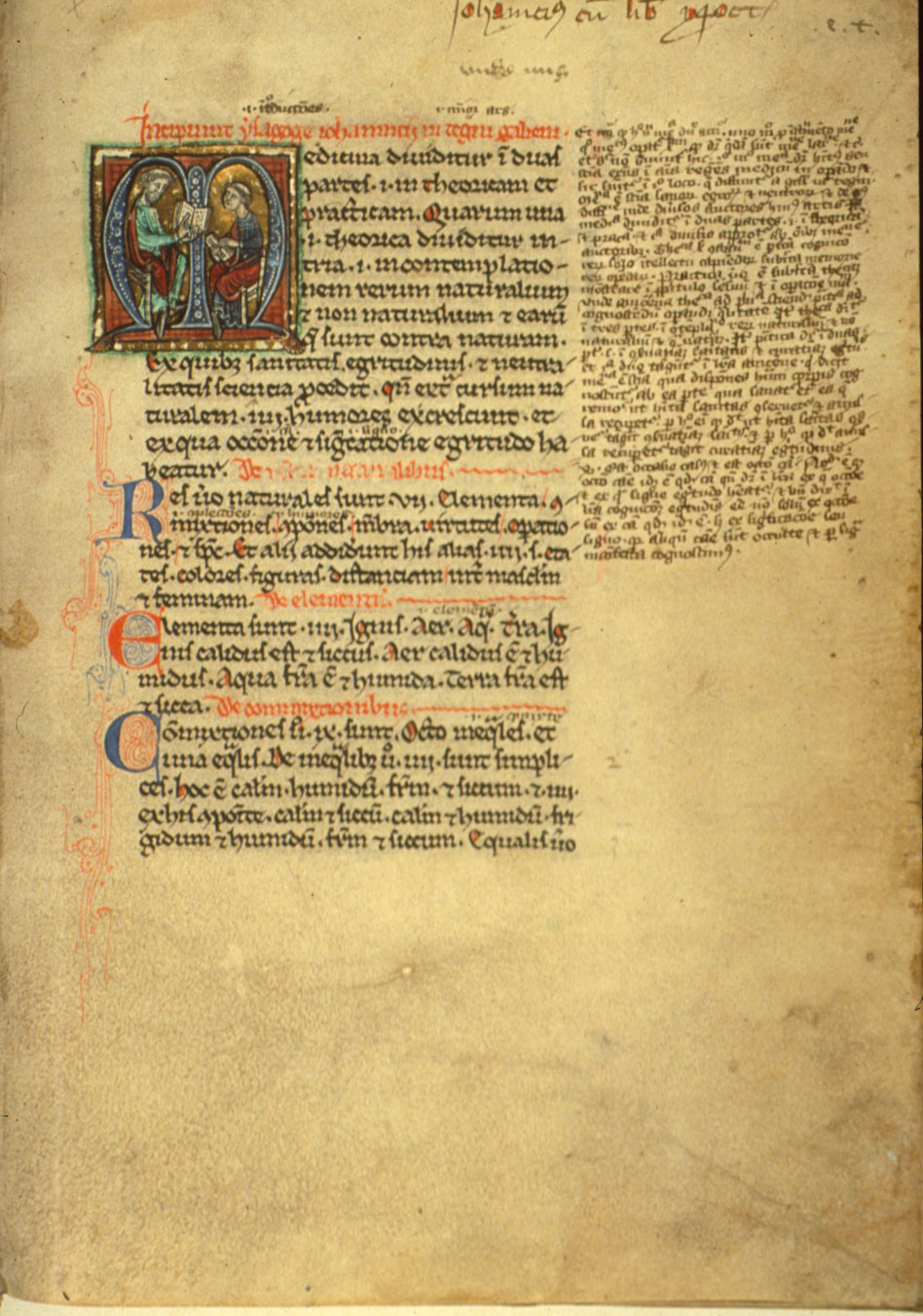

The "House of Wisdom" (''Bayt al-Hikmah'') was a major intellectual center during the reign of the Abbasids and was a major component of the Translation Movement and the Islamic Golden Age. The library was filled with many different authors and translated books from the Greek, Persian, and Indian civilizations.

The translation process in the House of Wisdom was very meticulous. Depending on the area of study of a certain book that was being translated, a specific person or group of people would be responsible for those translations. In example, the translation of engineering and mathematical works was overseen by Abū Jaʿfar Ibn Mūsa Ibn Shākir and his family, translations of philosophy and celestial movement was given to Ibn Farkhān al-Tabarī and Yaʿqūb al-Kindī, and Ibn Ishāq al-Harānī was in charge of translations involving the study of medicine. These translators were also from many different cultural, religious, and ethnic backgrounds, including Persians, Christians, and Muslims, all working to develop a well-rounded inventory of educational literature in the House of Wisdom for the Abbasid Caliphate. Once translation was finished the books would need to be copied and bound. The translation would be sent to an individual with very precise and skillful handwriting abilities. When finished, the pages would be bound together with a cover and decorated and would be catalogued and placed in a specific ward of the library. Multiple copies of the book would also be made to be distributed across the empire.

Historically, the House of Wisdom is a story of many successes. In 750 AD, the Abbasid's overthrew the Ummayad Caliphate, becoming the ruling power in the Islamic world. In 762 AD, Abu Jaʿfar Abdallah ibn Muhammad al-Mansur, the second Abbasid Caliph, decided to move the capital of the empire to his newly built city of Baghdad in Iraq from Damascus, which was in Syria. Al-Mansur was very cognizant of the need to cultivate intellect and wanted to advance and magnify the status of the Islamic people and their culture. As a result, he established a library, the House of Wisdom, in Baghdad where scholars and students could study new material, formulate new ideas, transcribe literature of their own, and translate various works from around the world into the Arabic language. Al-Mansur's descendants were also active in the cultivation of intellect, especially in the area of translation. Under the rule of Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid (better known as al-Maʿmun) the House of Wisdom thrived, acquiring a large amount of support and recognition. Al-Maʿmun would send scholars all over the civilized world to retrieve various scientific and literary works to be translated. The head translator at the time, Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi, who was a Christian Arab of al-Hira, is believed to have translated over one hundred books, including the work ''On Anatomy of the Veins and Arteries'' by Galen. Due to the translation movement under al-Maʿmun, the House of Wisdom was one of the largest repositories of scientific and literary books in the world at the time and remained that way until the Siege of Baghdad in 1258 AD. The destruction and pillaging of Baghdad by the Mongols also included the destruction of the House of Wisdom, however, the books and other works inside were taken to Maragha by Hulagu Khan and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.

Historically, the House of Wisdom is a story of many successes. In 750 AD, the Abbasid's overthrew the Ummayad Caliphate, becoming the ruling power in the Islamic world. In 762 AD, Abu Jaʿfar Abdallah ibn Muhammad al-Mansur, the second Abbasid Caliph, decided to move the capital of the empire to his newly built city of Baghdad in Iraq from Damascus, which was in Syria. Al-Mansur was very cognizant of the need to cultivate intellect and wanted to advance and magnify the status of the Islamic people and their culture. As a result, he established a library, the House of Wisdom, in Baghdad where scholars and students could study new material, formulate new ideas, transcribe literature of their own, and translate various works from around the world into the Arabic language. Al-Mansur's descendants were also active in the cultivation of intellect, especially in the area of translation. Under the rule of Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid (better known as al-Maʿmun) the House of Wisdom thrived, acquiring a large amount of support and recognition. Al-Maʿmun would send scholars all over the civilized world to retrieve various scientific and literary works to be translated. The head translator at the time, Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi, who was a Christian Arab of al-Hira, is believed to have translated over one hundred books, including the work ''On Anatomy of the Veins and Arteries'' by Galen. Due to the translation movement under al-Maʿmun, the House of Wisdom was one of the largest repositories of scientific and literary books in the world at the time and remained that way until the Siege of Baghdad in 1258 AD. The destruction and pillaging of Baghdad by the Mongols also included the destruction of the House of Wisdom, however, the books and other works inside were taken to Maragha by Hulagu Khan and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.

Notable Translators

; Abu Zaid Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi Abu Zaid Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi was a profound

Abu Zaid Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi was a profound Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, philosopher, author

An author is the writer of a book, article, play, mostly written work. A broader definition of the word "author" states:

"''An author is "the person who originated or gave existence to anything" and whose authorship determines responsibility f ...

and leading translator

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

in the House of Wisdom . He was born at Hira (Iraq) in 809 AD and spent most of his youth in Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

where he learned Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

and Syriac. He was affiliated with the Syrian Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

Christian Church, and was brought up as a Nestorian Christian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

long before the rise of Islam. Hunayn was eager to continue his education, so he followed his father's footsteps and moved to Baghdad to study medicine. Hunayn was an important figure in the evolution of Arabic Medicine

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

and was best known for his translations of famous Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Middle Eastern

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europea ...

authors. He had a complete mastery of Greek, which was the science language of the time. Hunayn's knowledge of Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, Syriac, and Arabic exceeded that of previous prevalent translators, which enabled him to revise their erroneous renditions. Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

, Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

, and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

were just a few of many writers that Hunayn used for his translated publications of medical and philosophical expositions. These translated treatises, in turn, became the backbone of Arabic Science.

As he began his path into medicine in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

, he had the privilege to study under one of the most renowned physicians in the city, Yūhannā ibn Māssawayh. Yūhannā and his colleagues dedicated their lives to the field of medicine. They showed little to no respect to the people of Hira where Hunayn was from because Hira was known to be a city flourished by commerce and banking rather than science and medicine. Due to this, he did not take Hunayn seriously as a student. Hunayn was a highly intelligent person who paid very close attention to detail and found many mistakes in his assigned medical textbooks, so would often ask difficult questions no one at his school had the answer to. Eventually, Yūhannā became so frustrated that he gave up his rights as his teacher and blatantly told Hunayn that he does not have the ability to pursue this career.

Hunayn had a strong mindset and refused to let Yūhannā get in his way. He left Baghdad for several years, and during his absence he studied the history and language of Greek. When he returned, he displayed his newly acquired skills by being able to recite and translate the works of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the '' Iliad'' and the '' Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of ...

and Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

. He began translating a large number of Galen's texts including “Anatomy of the Veins and Arteries”, “Anatomy of the Muscles”, “Anatomy of the Nerves”, “On Sect”, and many more in the upcoming future.

Everyone was astonished at his amazing talent especially Yūhannā, so the two reconciled and would later collaborate on several occasions. Hunayn, his son Ishaq, his nephew Hubaysh, and fellow colleague Isa ibn Uahya became very involved in translating medicinal and science texts. This led to the beginning of Hunayn's success into the translation movement, where he interpreted the works of famous Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

figures: Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

, Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

, and Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

. He was also constantly fixing defective manuscripts translated by other writers. Hunayn would collect different books based around the subject he was translating, and strove to make the text as clear as possible for readers. Because his translation methods were impeccable, it was not long until Hunayn became famous. Unlike other translators during the Abbasid period

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, he did not translate texts word for word. Hunayn had a specific way of absorbing information by attempting to attain the meaning of the subject prior to rewriting it, which was very rare to witness during his time. After he grasped a proficient understanding of the piece, he would rephrase his knowledge of it in either the Syriac or Arabic language onto a new manuscript.

Hunayn, his son Ishaq Ibn Hunayn, his nephew Hubaysh Ibn al-Hasan al-Aʿsam, and fellow colleague Isa Ibn Uahya became very involved in working together on translating medicinal

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practic ...

, science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

, and philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Som ...

texts. Ishaq and Hunayn were important contributors in Hunayn's translations and active members of his school. His son mastered the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

, and Syriac language to be able to follow into father's footsteps. At the beginning of his career, Hunayn was very critical of his son's work, and even corrected his Arabic translations of "On the Number of Syllogisms". However, Ishaq was more interested in philosophy and would go on to translate several famous philosophical writings such as ''That the Prime Mover is Immobile'' and pieces of Galen's ''On Demonstration''. He continued his passion for translations even after his father's death in 873 AD.

Ramifications of the Translation Movement

Lack of original Greek texts

From the middle of the eighth century to the end of the tenth century, a very large amount of non-literary and non-historicalsecular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

Greek books were translated into Arabic. These included books that were accessible throughout the Eastern Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

and the near east, according to the documentation from a century and a half of Graeco-Arabic scholarship. The Greek writings from Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

, Roman, and late antiquity times that did not survive in the original Greek text were all vulnerable to the translator and the powers they had over them when completing the translation. It was not uncommon to come across Arabic translators who added their own thoughts and ideas into the translations. Ninth century Arab Muslim philosopher al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

, for example, viewed Greek texts as a resource in which he was able to employ new ideas and methods off of, thus, re-inventing philosophy. Al-Kindi used the Greek texts as outlines used to fix the weaknesses and finish what they left unfinished. Translating also meant new information could be added in, while some could potentially be taken out depending on what the translator's goal was. Another example of this is found in the Arabic translator's approach to Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

's astronomy in the ''Almagest''. The ''Almagest'' was critiqued and modified by Arabic astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either o ...

s for many generations. The modifications were made based on Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

thought, most coming from Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

. As a result, this led to many new developments. When discussing the development of Arabic science, Greek heritage is an important area to cover. At the same time, in order to receive a complete understanding of Greek science there are parts that have only survived in Arabic that must also be taken into account. For example, Apollonius' ''Conics'' books V to VII and Diophantus' ''Arithmetica'' books IV to VII. The two listed are items of Greek origin that have only survived in their Arabic translation. The circumstance is the same for the relationship between Latin and Greek science, which requires the analysis of Greek texts translated into Arabic and then into Latin. Translation entails viewpoints from one angle, the angle of the one performing the translation. The full analysis and journey of the translated pieces are key components in the overarching theme behind the piece.

See also

*Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

* Science in the medieval Islamic world

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate an ...

* Hellenizing School, an analogue with Armenians

References

Further reading

*Dimitri Gutas

Dimitri Gutas ( el, Δημήτρης Γούτας; born 1945, in Cairo) is an American Arabist and Hellenist specialized in medieval Islamic philosophy, who serves as professor emeritus of Arabic and Islamic Studies in the Department of Near East ...

(2012). Greek Thought, Arabic Culture. The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early 'Abbasaid Society (2nd-4th 5th-10th centuries)

'. Routledge.

External links

*{{SEP, arabic-islamic-greek, Greek Sources in Arabic and Islamic Philosophy, Cristina D'Anconain which the

Barmakids

The Barmakids ( fa, برمکیان ''Barmakiyân''; ar, البرامكة ''al-Barāmikah''Harold Bailey, 1943. "Iranica" BSOAS 11: p. 2. India - Department of Archaeology, and V. S. Mirashi (ed.), ''Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era'' vol ...

play a considerable role. They also translated Indian mathematics books of Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the '' Aryabhatiya'' (whi ...

and Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the '' Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established doctrine of Brahma", dated 628), a theoretical tr ...

. Arabs were mostly responsible for spreading of Indian number system and arithmetic throughout the world.

Science in the medieval Islamic world

Medieval Iraq

History of translation

9th century in the Abbasid Caliphate

Abbasid literature