Goodbye to Berlin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Goodbye to Berlin'' is a 1939 novel by Anglo-American writer Christopher Isherwood set during the waning days of the

''Goodbye to Berlin'' received positive reviews by newspaper critics and contemporary writers. Critics praised Isherwood's "flair for sheer story-telling" and his ability to spin "an engrossing tale without bothering you with a plot." In a review for ''

''Goodbye to Berlin'' received positive reviews by newspaper critics and contemporary writers. Critics praised Isherwood's "flair for sheer story-telling" and his ability to spin "an engrossing tale without bothering you with a plot." In a review for ''

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

. The novel recounts Isherwood's 1929–1932 sojourn as a pleasure-seeking British expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country. In common usage, the term often refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, or artists taking positions outside their home country, either ...

on the eve of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's ascension as Chancellor of Germany and consists of a "series of sketches of disintegrating Berlin, its slums and nightclubs and comfortable villas, its odd maladapted types and its complacent burghers." The novel's plot recounts factual events in Isherwood's life, and most of the novel's characters were based upon actual persons. The insouciant flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee height was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered accepta ...

Sally Bowles

Sally Bowles () is a fictional character created by English-American novelist Christopher Isherwood and based upon 19-year-old cabaret singer Jean Ross. The character debuted in Isherwood's 1937 novella ''Sally Bowles'' published by Hogarth Press ...

was based on teenage cabaret singer Jean Ross

Jean Iris Ross Cockburn ( ; 7 May 1911 – 27 April 1973) was a British writer, political activist, and film critic. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), she was a war correspondent for the '' Daily Express'' and is thought to have been ...

who became Isherwood's intimate friend during his sojourn and, after an unplanned pregnancy, she had a near-fatal abortion which the shy gay author facilitated.

While Ross recovered from the abortion procedure, the political situation rapidly deteriorated in Germany. As Berlin's daily scenes featured "poverty, unemployment, political demonstrations and street fighting between the forces of the extreme left and the extreme right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

," Isherwood realised that he must flee the country. Following the Enabling Act

An enabling act is a piece of legislation by which a legislative body grants an entity which depends on it (for authorization or legitimacy) the power to take certain actions. For example, enabling acts often establish government agencies to carr ...

which cemented Hitler's power, Isherwood fled Germany and returned to England. Afterwards, Berlin's seedy cabarets were shuttered by the Nazis, and many of Isherwood's cabaret friends fled abroad or perished in concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s. These factual events served as the genesis for Isherwood's Berlin stories.

The novel received positive reviews by newspaper critics and contemporary writers. Critic Anne Margaret Angus praised Isherwood's literary mastery in conveying the ingravescent despair of Berlin's denizens and "their hopeless clinging to the pleasures of the moment". She believed Isherwood skillfully evoked "the psychological and emotional hotbed which forced the growth of that incredible tree, 'national socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Naz ...

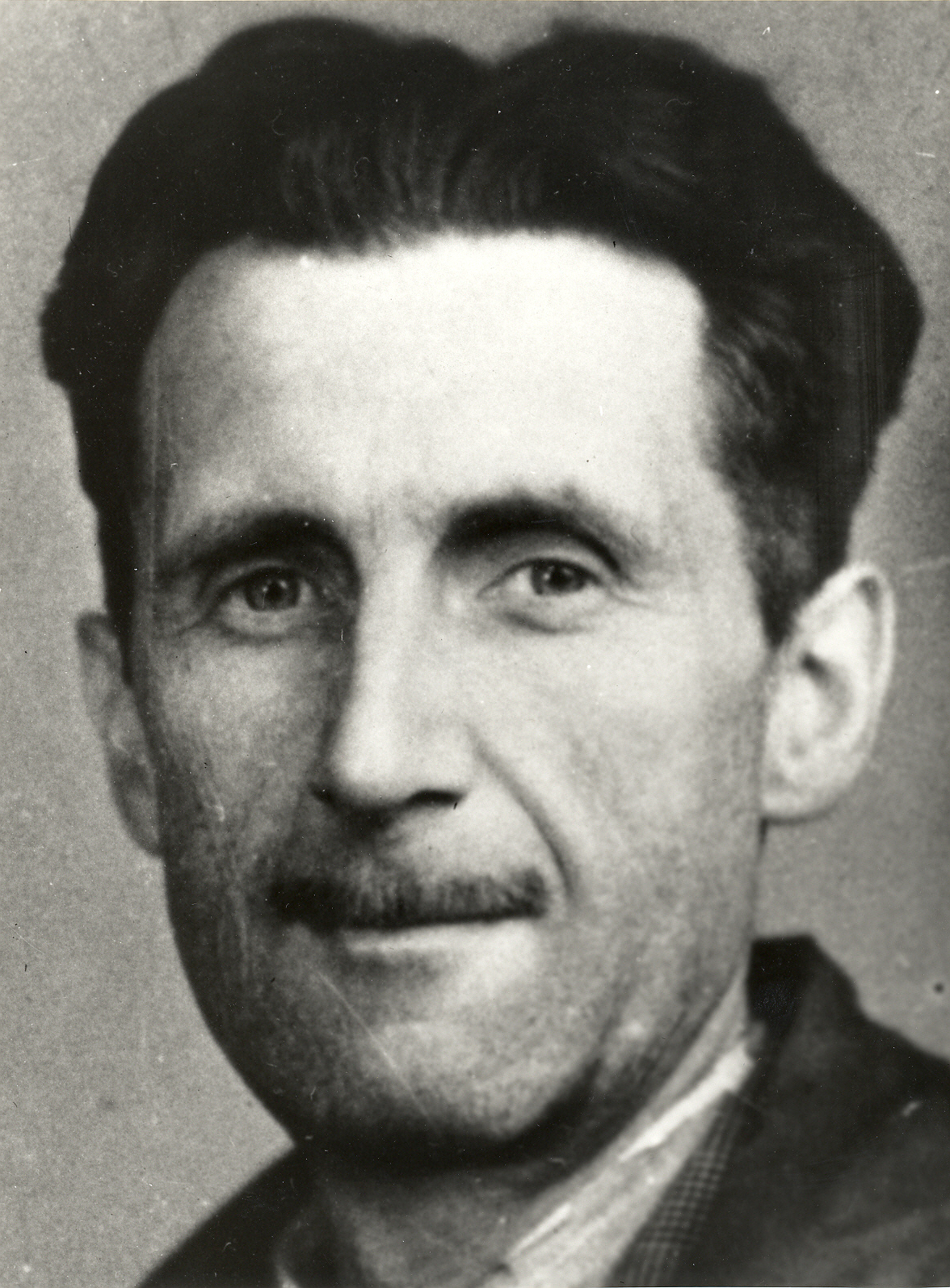

'." George Orwell hailed the novel for its "brilliant sketches of a society in decay". "Reading such tales as this," Orwell wrote, "the thing that surprises one is not that Hitler came to power, but that he did not do so several years earlier."

The 1939 novel was republished together with Isherwood's 1935 novel, '' Mr Norris Changes Trains'', in a 1945 collection titled ''The Berlin Stories

''The Berlin Stories'' is a 1945 anthology by Anglo-American writer Christopher Isherwood consisting of two novels: ''Mr Norris Changes Trains'' (1935) and ''Goodbye to Berlin'' (1939). The two novels are set in Jazz Age Berlin between 1930 and ...

''. Literary critics praised the collection as deftly capturing the bleak nihilism of the Weimar period. In 2010, ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' magazine hailed the collection as one of the 100 Best English-language novels of the 20th century. ''Goodbye to Berlin'' was adapted into the 1951 Broadway play ''I Am a Camera

''I Am a Camera'' is a 1951 Broadway play by John Van Druten adapted from Christopher Isherwood's 1939 novel ''Goodbye to Berlin'', which is part of '' The Berlin Stories''. The title is a quotation taken from the novel's first page: "I am a cam ...

'', the 1966 musical ''Cabaret'', and the 1972 film of the same name. According to critics, the novel's character Sally Bowles purportedly inspired Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

's character Holly Golightly in his 1958 novella '' Breakfast at Tiffany's''.

Biographical context

The autobiographical novel recounts Christopher Isherwood's extended residence in Jazz AgeBerlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

and describes the pre-Nazi social milieu as well as the colourful persons he encountered. While sojourning in the city, Isherwood socialised with a blithe coterie of expatriate writers that included W.H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by th ...

, Edward Upward

Edward Falaise Upward, FRSL (9 September 1903 – 13 February 2009) was a British novelist and short story writer who, prior to his death, was believed to be the UK's oldest living author. Initially gaining recognition amongst the Auden Group as ...

, and Paul Bowles

Paul Frederic Bowles (; December 30, 1910November 18, 1999) was an American expatriate composer, author, and translator. He became associated with the Moroccan city of Tangier, where he settled in 1947 and lived for 52 years to the end of his ...

. As a gay man, Isherwood frequently interacted with marginalised enclaves of Berliners and foreigners who later would be at greatest risk from Nazi persecution, and various Berlin denizens befriended by Isherwood would later flee abroad or die in labour camps

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (espec ...

.

The novel's most memorable character—the "divinely decadent": "Sally seems satisfied to be divinely decadent...": "The Sally character herself is this century's darling of divine decadence, an odd measure of how dear to us is this fiction of the 'shocking' British/American vamp in Weimar Berlin." Sally Bowles

Sally Bowles () is a fictional character created by English-American novelist Christopher Isherwood and based upon 19-year-old cabaret singer Jean Ross. The character debuted in Isherwood's 1937 novella ''Sally Bowles'' published by Hogarth Press ...

—was based upon 19-year-old flapper Jean Ross

Jean Iris Ross Cockburn ( ; 7 May 1911 – 27 April 1973) was a British writer, political activist, and film critic. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), she was a war correspondent for the '' Daily Express'' and is thought to have been ...

with whom Isherwood briefly shared lodgings at Nollendorfstraße 17 in Schöneberg

Schöneberg () is a locality of Berlin, Germany. Until Berlin's 2001 administrative reform it was a separate borough including the locality of Friedenau. Together with the former borough of Tempelhof it is now part of the new borough of Tempe ...

. Much like the character in the novel, Ross was a sexually promiscuous young woman and a bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

chanteuse

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engli ...

in lesbian bar

A lesbian bar (sometimes called a "women's bar") is a drinking establishment that caters exclusively or predominantly to lesbian women. While often conflated, the lesbian bar has a history distinct from that of the gay bar.

Significance

Les ...

s and second-rate cabarets. Isherwood visited these dingy nightclubs to hear Ross sing, and he described her singing talent as mediocre: "She had a surprisingly deep, husky voice. She sang badly, without any expression, her hands hanging down at her sides—yet her performance was, in its own way, effective because of her startling appearance and her air of not caring a curse of what people thought of her."Likewise, mutual acquaintance

Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by th ...

recalled that Ross' singing ability was quite underwhelming and forgettable: "In my mind's eye, I can see her now in some dingy bar standing on a platform and singing so inaudibly that I could not hear her from the back of the room where I was discreetly seated."

Although Isherwood sometimes had sex with women, Ross—unlike the fictional character Sally—never tried to seduce Isherwood, although they were forced to share a bed whenever their tiny flat became overcrowded with visiting revelers. Instead, Isherwood settled into a same-sex relationship with a working-class German boy named Heinz Neddermeyer, while Ross entered into a variety of heterosexual liaisons, including one with the blond musician Peter van Eyck, the future star of Henri-Georges Clouzot's ''The Wages of Fear

''The Wages of Fear'' (french: Le Salaire de la peur) is a 1953 French thriller film directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot, starring Yves Montand, and based on the 1950 French novel ''Le Salaire de la peur'' (lit. "The Salary of Fear") by Georges A ...

''.

Soon after their separation, Ross realised she was pregnant. As a personal favour to Ross, Isherwood helped facilitate an abortion procedure. Ross nearly died as a result of the botched abortion procedure. Isherwood visited Ross in the hospital following her abortion. Wrongly assuming he was the father, the hospital staff despised him for impregnating Ross and then callously forcing her to have an abortion. These tragicomic events inspired Isherwood to write his 1937 novella ''Sally Bowles'' and serves as its narrative climax.

While Ross recovered from the abortion procedure, the political situation rapidly deteriorated in Germany. As Berlin's daily scenes featured "poverty, unemployment, political demonstrations and street fighting between the forces of the extreme left and the extreme right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

," Isherwood, Spender, and other British nationals soon realised that they must leave the country. "There was a sensation of doom to be felt in the Berlin streets," Spender recalled.

Two weeks after the Enabling Act

An enabling act is a piece of legislation by which a legislative body grants an entity which depends on it (for authorization or legitimacy) the power to take certain actions. For example, enabling acts often establish government agencies to carr ...

cemented Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's power, Isherwood fled Germany and returned to England on 5 April 1933. Afterwards, most of Berlin's seedy cabarets were shuttered by the Nazis, and many of Isherwood's cabaret friends later fled abroad or perished in concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s. These factual events served as the genesis for Isherwood's Berlin tales.

Following her departure from Germany, Ross became a devout Stalinist and a lifelong member of Harry Pollitt

Harry Pollitt (22 November 1890 – 27 June 1960) was a British communist who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) from 1929 to September 1939 and again from 1941 until his death in 1960. Pollitt spent ...

's Communist Party of Great Britain. She served as a war correspondent for the '' Daily Express'' during the subsequent Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

(1936–39), and she is alleged to have been a propagandist for Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's Comintern. A skilled writer, Ross also worked as a film critic for the ''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were ...

'', and her criticisms of early Soviet cinema

The cinema of the Soviet Union includes films produced by the constituent republics of the Soviet Union reflecting elements of their pre-Soviet culture, language and history, albeit they were all regulated by the central government in Moscow. M ...

were later described by critics as ingenious works of " dialectical sophistry". She often wrote political criticism, anti-fascist polemics, and manifestos. For the remainder of her life, Ross believed the public association of herself with the naïve and apolitical character of Sally Bowles occluded her lifelong work as a professional writer and political activist.

Ross particularly resented how Isherwood depicted Sally Bowles expressing antisemitic bigotry. In the original 1937 novella ''Sally Bowles'', the character laments having sex with an "awful old Jew" to obtain money. Ross' daughter, Sarah Caudwell

Sarah Caudwell was the pseudonym of Sarah Cockburn (/ˈkoʊbərn/ KOH-bərn; 27 May 1939 – 28 January 2000), a British barrister and writer of detective stories. She is best known for a series of four murder stories written between 1980 and ...

, said such racial bigotry "would have been as alien to my mother's vocabulary as a sentence in Swahili; she had no more deeply rooted passion than a loathing of racialism and so, from the outset, of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

."

Due to her unyielding dislike of fascism, Ross was incensed that Isherwood had depicted her as thoughtlessly allied in her beliefs "with the attitudes which led to Dachau and Auschwitz". In the early 21st century, some writers have argued the antisemitic remarks in "Sally Bowles" are a reflection of Isherwood's own much-documented racial prejudices. In Peter Parker's 2004 biography, he writes that Isherwood was "fairly anti-Semitic to a degree that required some emendations of the Berlin novels when they were republished after the war".

Although Isherwood's stories about the Jazz Age nightlife of Weimar-era Berlin became commercially successful, Isherwood later denounced his writings. He lamented that he had not understood the suffering of the people which he depicted. He stated that 1930s Berlin had been "a real city in which human beings were suffering the miseries of political violence and near-starvation. The 'wickedness' of Berlin's night-life was of the most pitiful kind; the kisses and embraces, as always, had price-tags attached to them.... As for the 'monsters', they were quite ordinary human beings prosaically engaged in getting their living through illegal methods. The only genuine monster was the young foreigner who passed gaily through these scenes of desolation, misinterpreting them to suit his childish fantasy."

Plot summary

After relocating to Weimar-era Berlin in order to work on his novel, an English writer explores the decadent nightlife of the city and becomes enmeshed in the colorful lives of a diverse array of Berlin denizens. He acquires modest lodgings in a boarding house owned by Fräulein Schroeder, a caring landlady. At the boarding house, he interacts with the other tenants, including the brazen prostitute Fräulein Kost, who has a Japanese patron, and the decadentSally Bowles

Sally Bowles () is a fictional character created by English-American novelist Christopher Isherwood and based upon 19-year-old cabaret singer Jean Ross. The character debuted in Isherwood's 1937 novella ''Sally Bowles'' published by Hogarth Press ...

, a young English flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee height was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered accepta ...

who sings tunelessly in a seedy cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining o ...

called "The Lady Windermere". Due to a mutual lack of funds, Christopher and Sally soon become roommates, and he learns a great deal about her sex life as well as her coterie of "marvelous" lovers.

When Sally becomes pregnant after a brief fling, Christopher facilitates an abortion, and the painful incident draws them closer together. When he visits Sally at the hospital, the hospital staff assume he is Sally's impregnator and despise him for forcing her to have an abortion. Later during the summer, Christopher resides at a beach house near the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

with Peter Wilkinson and Otto Nowak, a gay couple who are struggling with their sexual identities. Jealous of Otto's endless flirtations with other men, Peter departs for England, and Christopher returns to Berlin to live with Otto's family, the Nowaks.

During this time, Christopher meets teenage Natalie Landauer whose wealthy Jewish family owns a department store. After the Nazis smash the windows of several Jewish shops, Christopher learns that Natalie's cousin Bernhard is dead, likely murdered by the Nazis. Ultimately, Christopher is forced to leave Germany as the Nazis continue their ascent to power, and he fears that many of his beloved Berlin acquaintances are now dead.

Major characters

* Christopher Isherwoodan English writer who visits Berlin and becomes entangled in the lives of various locals. The character is based upon the author. Isherwood specifically relocated to poverty-stricken Berlin to avail himself of underage male prostitutes, and he was politically indifferent about the rise of fascism. Jean Ross later claimed that Sally Bowles' political indifference more closely resembled Isherwood himself and his hedonistic male friends, many of whom "fluttered around town exclaiming how sexy the storm troopers looked in their uniforms". Ross' opinion of Isherwood's political indifference was confirmed by Isherwood's acquaintanceW. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

who noted the young Isherwood "held no oliticalopinions whatever about anything".

* Sally Bowlesa British cabaret singer with whom Christopher briefly shares a small Nollendorfstrasse flat. She has a number of sexual liaisons, becomes pregnant, and undergoes an abortion. The character was based upon 19-year-old Jean Ross

Jean Iris Ross Cockburn ( ; 7 May 1911 – 27 April 1973) was a British writer, political activist, and film critic. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), she was a war correspondent for the '' Daily Express'' and is thought to have been ...

. Like Ross, Sally attended the exclusive Leatherhead School in Surrey, England, and hailed from a wealthy family. According to Isherwood, Sally should not be either viewed or interpreted as "a tart

A tart is a baked dish consisting of a filling over a pastry base with an open top not covered with pastry. The pastry is usually shortcrust pastry; the filling may be sweet or savoury, though modern tarts are usually fruit-based, sometimes wit ...

." Instead, Sally "is a little girl who has listened to what the grown-ups had said about tarts, and who was trying to copy those things".

* Fräulein Schroedera plump German landlady who owns the boarding house where Christopher and Sally reside. The character was based upon Fräulein Meta Thurau. According to Isherwood, Thurau "was tremendously intrigued by ean Ross'looks and mannerisms, her makeup, her style of dressing, and above all, her stories about her love affairs. But she didn't altogether like Jean. For Jean was untidy and inconsiderate; she made a lot of extra work for her landladies. She expected room service and sometimes would order people around in an imperious tone, with her English upper-class rudeness".

* Otto Nowaka very handsome and gamine

A gamine is a slim, often boyish, elegant young woman who is, or is perceived to be, mischievous, teasing or sexually appealing.

The word ''gamine'' is a French word, the feminine form of ''gamin'', originally meaning urchin, waif or playful, ...

teenage boy whose family briefly lodges Christopher after he returns from his vacation on the Baltic Sea. Otto was based on the bisexual teenager Walter Wolff who had been born in eastern Germany prior to its transfer to Poland after the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. Unwilling to become Polish citizens, Walter and his family moved to the Berlin slums after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Although irrepressibly merry, Wolff was described by Isherwood as an incorrigible narcissist who cared very little about the feelings of the men and women who pursued him.

* Peter Wilkinsonan English expatriate who sexually pursues the narcissistic Otto Nowak and then departs Germany due to Otto's flirtations with other men. The character was partly based on William Robson-Scott, a lecturer in English at Berlin University

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

. Robson-Scott "was at this time homosexual and, according to Isherwood, occasionally paid boys to beat him." As three family members had died before he turned fifteen years old, Robson-Scott was "deeply apprehensive about life, believing that if one loved somebody the natural consequence of this would be their death."

* Natalie Landaueran earnest young Jewish woman whose affluent family pays Christopher for English lessons. Natalie's cousin Bernhard is later murdered, presumably by Nazi street thugs. The character was loosely based upon Gisa Soleweitschick. According to Soleweitschick, her mother had discerned quickly that Isherwood was "not interested in girls" and, accordingly, she trusted him as her daughter's unchaperoned companion. However, Gisa herself did not realise that Isherwood was gay, and she attributed his lack of sexual advances to his "fine English manners."

* Klaus Linkean itinerant musician who impregnates Sally and is based upon Peter van Eyck. Although some biographers identify van Eyck as Jewish, others posit van Eyck was the wealthy scion of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

n landowners in Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

. As an aristocrat, he was expected by his family to embark upon a military career but he became interested in jazz as a young man and pursued musical studies in Berlin.

* Clivea wealthy playboy based upon American expatriate John Blomshield who inspired the enigmatic character of Baron Maximilian von Heune in the 1972 film adaptation.: "Although married, Blomshield was entirely homosexual and had the sort of unlimited funds that enabled him to enjoy the city in a way Isherwood never could. He was also generous, and decided that Isherwood, Spender and Jean Ross should be given a taste of the high life. 'He altered our lives for about a week,' Spender recalled—a week Isherwood re-created in ''Goodbye to Berlin'', where Blomshield inspired the character of Clive, the rich young man who takes up, treats and then unceremoniously dumps Chris and Sally." According to contradictory sources, Blomshield sexually pursued both Isherwood and Ross for a short while in Berlin, and he invited them to accompany him on a trip abroad to the United States. When they had agreed to go, he then abruptly disappeared without saying goodbye.: "... the American thrilled them by inviting them to come with him to the States and then dashed their hopes by leaving Berlin abruptly, without saying goodbye." Blomshield bluntly terminated his relationships in the same manner that Clive ends his affair with Sally.

Critical reception

''Goodbye to Berlin'' received positive reviews by newspaper critics and contemporary writers. Critics praised Isherwood's "flair for sheer story-telling" and his ability to spin "an engrossing tale without bothering you with a plot." In a review for ''

''Goodbye to Berlin'' received positive reviews by newspaper critics and contemporary writers. Critics praised Isherwood's "flair for sheer story-telling" and his ability to spin "an engrossing tale without bothering you with a plot." In a review for ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'', novelist L. P. Hartley wrote that Isherwood "is an artist to his finger-tips. If he were not, these sketches of pre-Hitlerian Berlin (the Nazi regime is coming into force when the book closes) would make still sadder reading, for all around is poverty, suspicion, and the threat of violence." Hartley concluded by noting that "if his glimpses are oblique and partial, they are also revealing: ''Goodbye to Berlin'' is a historical as well as a personal record."

Critic Anne Margaret Angus praised Isherwood's mastery in conveying the ingravescent despair of Berlin's denizens, "with their febrile emotionalism" and "their hopeless clinging to the pleasures of the moment". She believed Isherwood skillfully evoked "the psychological and emotional hotbed which forced the growth of that incredible tree, 'national socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Naz ...

'." She concluded by noting that "suffering sometimes from too great restraint, his studies, when they do succeed, surely (and often painfully) enlarge our knowledge of human nature."

Contemporary writer and literary critic George Orwell likewise praised by the novel. Although Orwell believed the work to be inferior to Isherwood's earlier novel, '' Mr Norris Changes Trains'', he nonetheless believed that ''Goodbye to Berlin'' contained "brilliant sketches of a society in decay". In particular, Orwell singled out for praise the chapter titled "The Nowaks" which concerns a working-class Berlin family on the verge of destitution and disaster. "Reading such tales as this," Orwell observed, "the thing that surprises one is not that Hitler came to power, but that he did not do so several years earlier. The book ends with the triumph of the Nazis and Mr. Isherwood's departure from Berlin."

In her book '' Anti-Nazi Modernism: The Challenges of Resistance in 1930s Fiction'', author Mia Spiro remarks that "despite that which they could not know, the novels that Barnes, Isherwood, and Woolf wrote do reveal the historical, cultural, political, and social conditions in 1930s Europe that made the continent ripe for disaster".

Adaptations

The novel was adapted byJohn Van Druten

John William Van Druten (1 June 190119 December 1957) was an English playwright and theatre director. He began his career in London, and later moved to America, becoming a U.S. citizen. He was known for his plays of witty and urbane observation ...

into a 1951 Broadway play called ''I Am a Camera

''I Am a Camera'' is a 1951 Broadway play by John Van Druten adapted from Christopher Isherwood's 1939 novel ''Goodbye to Berlin'', which is part of '' The Berlin Stories''. The title is a quotation taken from the novel's first page: "I am a cam ...

''. The play was a personal success for Julie Harris

Julia Ann Harris (December 2, 1925August 24, 2013) was an American actress. Renowned for her classical and contemporary stage work, she received five Tony Awards for Best Actress in a Play.

Harris debuted on Broadway in 1945, against the wish ...

as the insouciant Sally Bowles, winning her the first of her five Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual ce ...

s for Best Leading Actress, although it earned the infamous review by Walter Kerr

Walter Francis Kerr (July 8, 1913 – October 9, 1996) was an American writer and Broadway theatre critic. He also was the writer, lyricist, and/or director of several Broadway plays and musicals as well as the author of several books, genera ...

, "Me no Leica." The play's title is a quote taken from the novel's first page ("I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking."). The play was then adapted into a commercially successful film, also called ''I Am a Camera

''I Am a Camera'' is a 1951 Broadway play by John Van Druten adapted from Christopher Isherwood's 1939 novel ''Goodbye to Berlin'', which is part of '' The Berlin Stories''. The title is a quotation taken from the novel's first page: "I am a cam ...

'' (1955), featuring Laurence Harvey, Shelley Winters

Shelley Winters (born Shirley Schrift; August 18, 1920 – January 14, 2006) was an American actress whose career spanned seven decades. She appeared in numerous films. She won Academy Awards for ''The Diary of Anne Frank'' (1959) and ''A Patch o ...

and Julie Harris, with screenplay by John Collier and music by Malcolm Arnold

Sir Malcolm Henry Arnold (21 October 1921 – 23 September 2006) was an English composer. His works feature music in many genres, including a cycle of nine symphonies, numerous concertos, concert works, chamber music, choral music and music ...

.

The book was next adapted into the Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual ce ...

-winning musical ''Cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining o ...

'' (1966) and the film ''Cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining o ...

'' (1972) for which Liza Minnelli won an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

for playing Sally. Isherwood was highly critical of the 1972 film due to what he perceived as its negative portrayal of homosexuality. He noted that, "in the film of ''Cabaret'', the male lead is called Brian Roberts. He is a bisexual Englishman; he has an affair with Sally and, later, with one of Sally's lovers, a German baron... Brian's homosexual tendency is treated as an indecent but comic weakness to be snickered at, like bed-wetting."

Isherwood's friends, especially the poet Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by th ...

, often lamented how the cinematic and stage adaptations of ''Goodbye to Berlin'' glossed over Weimar-era Berlin's crushing poverty: "There is not a single meal, or club, in the movie ''Cabaret,'' that Christopher and I could have afforded n 1931" Spender, Isherwood, W.H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

and others asserted that both the 1972 film and 1966 Broadway musical deleteriously glamorised the harsh realities of the 1930s Weimar era.

Influence

According to literary critics, the character of Sally Bowles in ''Goodbye to Berlin'' inspiredTruman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

's Holly Golightly in his later novella '' Breakfast at Tiffany's''.: "Truman Capote's Holly Golightly... the latter of whom is a tribute to Isherwood and his Sally Bowles..." Critics have alleged that both scenes and dialogue in Capote's 1958 novella have direct equivalencies in Isherwood's earlier 1937 work. Capote had befriended Isherwood in New York in the late 1940s, and Capote was an admirer of Isherwood's novels.

References

Notes

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Goodbye To Berlin 1939 British novels 1930s LGBT novels Novels by Christopher Isherwood British autobiographical novels Novels set in Berlin Hogarth Press books Works set in cabarets British novels adapted into plays British novels adapted into films